Key Points

-

Offers a method for measuring important aspects of patient-perceived oral health, as part of a routine and concise patient satisfaction survey.

-

Confirms that oral health self perceptions seem to be a little less positive in older patients.

-

Suggests asking questions such as these in patient surveys might also help to reinforce 'caring' and patient focus from a practice team.

Abstract

Aim To investigate the measurement of oral health self perceptions, as part of a concise patient survey, and to consider the potential value of including this aspect in survey instruments.

Method In 2011, the data collected from 42,794 patients attending 276 practices participating in a voluntary accreditation programme patient survey were reviewed, with a particular emphasis on three oral health impact questions (OHIQs) included in the instrument. These three questions were about comfort (pain), function and dental appearance.

Results Patient self perceptions of oral health varied with age. For each of the three OHIQs the percentage of patients reporting 'ideal' health fell with age to some extent, although for each of the OHIQs the percentage of patients reporting 'unacceptable' health remained below 3% and varied little with age. Statistically significant variations from the mean scores for these OHIQs were observed for some of the participating practices, which would not be explained by age variations in their patient sample alone.

Conclusion Patient surveys are a useful opportunity to elicit collective feedback from patients on self perceived oral health. When results are benchmarked they can inform practices, particularly when reviewed together with additional relevant data, of opportunities to develop clinical services to produce still higher standards of oral health and wellbeing for their patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The use of patient surveys to monitor perceived outcomes is encouraged as part of the compliance framework of the Care Quality Commission in England (www.cqc.org.uk). In this regard it is self evident that reliable customer surveys can improve the performance of any organisation if results are acted upon. Newsome and Wright1 found that the dental patient surveys that they reviewed tended to ask questions about:

-

1

Technical competence

-

2

Interpersonal factors

-

3

Convenience

-

4

Cost

-

5

Facilities.

However, it has not been common practice for dental satisfaction surveys to include oral health impact questions.

In 1994, Slade and Spencer2 developed the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP). This is a questionnaire designed to measure patient perceptions of the impact of oral health issues on their lives. They compiled the original questionnaire following interviews with 64 patients from Adelaide, South Australia, who were deliberately selected to have experienced a range of oral diseases with consequent social impact. This group of patients made a total of 535 statements, using their own words, about the consequences of oral disorders.

The original 535 statements were collated into the seven dimensions shown in Table 1, drawn from a model developed by Locker.3

Locker had based these dimensions on the World Health Organization's classification of impairments, disabilities and handicaps. However, Slade and Spencer themselves stated; 'the 49 questions constitute a lengthy questionnaire, and the average time for administration by an interviewer is 17 minutes.'2

A shorter 14 question version was developed by Slade4 called unsurprisingly the OHIP14! This version was used in the Adult Dental Health Survey 20095 to assess patient perceived outcomes and impacts.

Burke and Wilson6 described three patient perception questions around comfort, function, and appearance as central to their index. This was the Oral Health Index (OHX). The index also described scoring protocols for the assessment of caries, wear, periodontal disease, occlusion and soft tissue health.

Burke et al.7 described a modification of the OHX (the Denplan Excel Oral Health Score or OHS), which maintained the three questions and allocated 24% of the total score to patient perceptions. The remaining 76% of the score was allocated to the clinical examination of periodontal health, wear of teeth and restorations, the occlusion, caries status, and soft tissue health using very similar protocols to the OHX. The protocol for this index suggests that dentists ask the following three questions in order to assess comfort, function and appearance:

-

Is your mouth free from pain?

-

Can you comfortably chew an unrestricted diet?

-

Are you happy with the appearance of your teeth?

Ireland et al.8 also concluded that the following should be three of ten factors recommended in their minimum data set for oral health assessment:

-

Presence of oral pain

-

Patient satisfaction with appearance

-

Patient satisfaction with function.

It was against this background that Busby et al.9 developed a concise patient questionnaire designed to measure perceived outcomes on the issues of greatest importance to patients. This paper describes the development of the questionnaire used in this study of patient perceived oral health. There are only ten core questions in this instrument, covering issues which had been shown in a literature review by Busby10 to be of greatest importance to patients and therefore, ultimately, practice success. The concise and focused design of this questionnaire was found to encourage patients to respond (vide infra) and to make interpretation of the feedback for practices straightforward. This was helped by the use of only three grades of patient response: 'ideal', 'acceptable' and 'unacceptable'. The survey questions, which were developed with the help of Electoral Reform Services (www.electoralreform.co.uk, are reproduced in Table 2. Versions of the three oral health impact questions recommended by Burke et al.7 and Ireland et al.8 are included. This paper investigates the feedback which practices received in 2011, particularly in respect to patient perceived oral health, and discusses the potential value of this aspect of the survey.

Methods

During 2011, 276 practices participated in this patient survey as part of their commitment to Denplan Excel Accreditation (www.denplan.co.uk). Each accredited practice is obliged to participate in this survey every three years. (Denplan Excel Accreditation is a voluntary programme run by Denplan Ltd, details of which can be found on their web site.)

Participating practices were sent a supply of questionnaires and were requested to distribute them to consecutive patients attending over a time period of one month. Practices were advised to collect responses in a dedicated ballot box at the practice and then post them to Denplan Ltd for data analysis. The results were sent to the practices in a comprehensive 14 page document. At the heart of this report is the 'all patients' results chart, a mock up of which is presented for illustrative purposes for the fictional 'Practice X' in Figure 1. This chart plots the percentage of 'ideal' grades achieved by the practice against the National Reference Sample (NRS). In this regard, the NRS for 2011 was the average results achieved by all participating practices in 2010. The NRS is therefore a benchmark for participants. In any given year the NRS is based on the averages from all participants in the previous year. Where a score is statistically significantly different to the NRS on any issue (to a 90% certainty) this is highlighted in Table 3 (purple for lower, yellow for higher).

Practice teams were advised to meet and discuss their results, for example to ask the question 'why might this perception be occurring?' for those issues on which they score significantly below the NRS. Reports were also provided with breakdowns by patient type (Denplan, private fee per item or NHS), by patient age and by gender. This concise survey also includes a Reichheld net promoter score,11 a general level of service question and an opportunity for verbatim comments from patients. The Reichheld net promoter score is a customer loyalty measurement used by many organisations today.

Results

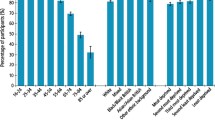

A total of 42,794 responses were received from the patients of 276 different practices, a mean of 155 responses per practice. Figure 2 shows the overall results on the ten core questions. This result is going forward to form the NRS for 2012. Figure 2 also shows the results from the first three months of operation of this survey in 2010, which formed the NRS for 2011. This was based on responses from 7,381 patients from 61 different practices. In both years there were less than 1% of responses recorded as 'unacceptable', indicating that the majority of responses which were not 'ideal' were 'acceptable'. In both years, the sample was made up of a similar proportion of different patient types as follows:

-

Denplan patients (63%)

-

Private fee per item patients (27%)

-

NHS patients (10%).

Table 4 presents the 2011 results for the three oral health impact questions (OHIQs) broken down by age group. One percent of all patients reported 'unacceptable' comfort, 2% 'unacceptable' function and 3% 'unacceptable appearance. The percentage reporting 'unacceptable' varied little across the age groups. Figure 3 illustrates the OHIQs by age group reporting 'ideal', while Table 5 presents the highest and the lowest 'ideal' and 'unacceptable' scores achieved by any practice on the OHIQs in 2011 with the minimum qualification that 50 responses had been received. (n = 235 practices attained more than 50 responses).

Discussion

As Busby et al.9 reported in the first paper describing the development of this concise survey, these results, from a group of volunteer practices, could not be considered to represent a random sample of UK dentists. They also reported that these patients appeared to perceive broadly favourable outcomes, but that it was possible, by focusing principally on the percentage of 'ideal' scores received, to measure statistically significant differences in perceived performance between practices and between the different aspects covered within a practice. Table 5 demonstrates the clear differences between the highest scoring and lowest scoring practices on each OHIQ.

Busby et al.9 also discuss the possibility of favourable patient selection when practices hand out questionnaires, if they fail to follow the protocol on consecutive patients. They stated:

''Performance' in the patient survey described in this paper is not linked to any award, or reward. Members are required to show that they act on the feedback. The primary purpose is to inform practice development. Using these methods the practice takes responsibility for the quality of the data they ultimately receive, which in turn is for their developmental benefit alone.'

This is still true for the 2011 results. The authors, along with Dillman et al.,12 would caution against using a patient survey to judge rewards or awards. The authors' view is that the function of a patient survey is to inform development.

So, what is the potential value of this feedback on self perceived oral health to participating practices? Results which are statistically significant to 90% certainty are highlighted on each practice report (Table 3). Accordingly, if an OIHQ result on 'ideal' scores is highlighted in blue, practices may be alerted to the possibility that their patients do not perceive such 'ideal' oral health on a particular issue as the average patient from the average practice in the programme. The example of practice X in Table 3 has been mocked up to illustrate the 'all patient' bar chart (Fig. 1). Practice X, in this illustration, would be alerted to the probability that their patients are not quite as happy with their dental appearance as is typical for the programme. They are 7% down on 'ideal' grades and have received 6% 'unacceptable' grades on this issue, double the mean percentage (this is highlighted in yellow - Table 3).

Overall, only a small number of 'unacceptable' responses were given. However, it is important to check the percentage of 'unacceptable' responses received. It was a different practice for each OHIQ that returned the highest percentage of 'unacceptable' responses.

Practices scoring significantly below the NRS for 'ideal' responses are encouraged to ask themselves 'why is this perception occurring?' This would be especially important if they were also receiving significantly more 'unacceptable' grades than average. Ultimately the practice team needs to 'diagnose' their potential problem and devise their own plan of action.

On the three OHIQs there are perhaps three common and plausible reasons why the proportion of ideal responses may be significantly lower than average:

-

1

The practice may be failing to use specific and focused questioning with every patient to elicit oral health impacts. Accordingly there may be an opportunity to develop their communication skills. If this is the case it might be confirmed if the scores are also lower than average for 'understanding' or 'explaining' in the survey results. Returning to the example of practice X in Table 3, it will be noticed that this was the case

-

2

The practice might be eliciting problems, but failing to act appropriately in order to solve them in every case. With these first two possibilities an audit of records could help to confirm the problem

-

3

They may have older patients than average for the NRS. Figure 3 illustrates the degree of difference in scoring between the age groups on OHIQs. However, age will not explain a higher number of 'unacceptable' responses as this seems to vary little between the age groups. Figure 3 also illustrates that age alone will not explain any wide negative variations from the NRS.

Differences in oral health perceptions between age groups are not only reflected by data from this survey, but can also be seen in the data from the 2009 Adult Dental Health Survey in England and Northern Ireland (ADHS).5 Unsurprisingly, older dentate patients seem to experience more negative oral health impacts than younger patients nationally. As a simple example, to quote from the ADHS 2009; '34% of dentate adults aged 55 to 64 reported experiencing physical pain occasionally or more often compared with 26% of dentate adults aged 16 to 24.'

Another, less likely, reason for a below average score might be a disproportionate number of patients being surveyed by the practice who were attending because of an urgent dental problem. This shows that responsibility for understanding the reason for a lower score, and any action needed as a result, must rest with the practice team themselves, who alone will be able to assess all the circumstances.

Finally, it may be considered that the use of a questionnaire distributed by the practice, such as this, may help to demonstrate a commitment to the wellbeing of patients. Consequently, a tool like this might not only be valuable by informing the practice of development opportunities, but also have value in practice marketing and promotion. Further research is needed to investigate the effect of using questionnaires such as this on patient perceptions of practices.

Conclusion

Patient surveys are a useful opportunity to elicit collective feedback from patients on self perceived oral health. When results are benchmarked they can inform practices, particularly when reviewed together with additional relevant data, of opportunities to develop clinical services to produce still higher standards of oral health and wellbeing for their patients.

References

Newsome P R, Wright G H . A review of patient satisfaction: 2. Dental patient satisfaction: an appraisal of recent literature. Br Dent J 1999; 186: 166–170.

Slade G D, Spencer A J . Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health 1994; 11: 3–11.

Locker D . Measuring oral health: a conceptual framework. Community Dent Health 1988; 5: 3–18.

Slade G D . Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997; 25: 284–290.

Adult Dental Health Survey 2009. London: The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2011.

Burke F J, Wilson N H . Measuring oral health: an historical view and details of a contemporary oral health index (OHX). Int Dent J 1995; 45: 358–370.

Burke F J, Busby M, McHugh S, Delargy S, Mullins A, Matthews R . Evaluation of an oral health scoring system by dentists in general dental practice. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 215–218.

Ireland R S, Jenner A M, Williams M J, Tickle M . A clinical minimum data set for primary dental care. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 663–667.

Busby M C, Burke F J, Matthews R, Cytra J, Mullins A . The development of a concise questionnaire designed to measure perceived outcomes on the issues of greatest importance to patients. Br Dent J 2012; 212: E11.

Busby M C . Measuring success in dental practice using patient feedback - a feasibility study. Birmingham: University of Birmingham MPhil Thesis.

Reichheld F . The ultimate question: driving good profits and true growth. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation, 2006.

Dillman D A, Smyth J D, Christian L M . Internet, mail and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design and method. 3rd ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Busby, M., Burke, F., Matthews, R. et al. Measuring oral health self perceptions as part of a concise patient survey. Br Dent J 213, 611–615 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.1135

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.1135