Key Points

-

One quarter of respondents rated their oral health as fair or worse, with a similar proportion reporting difficulties accessing routine care.

-

Most frequently reported barriers were 'no dentists taking patients', 'dentists only treating privately' and 'treatment too expensive'.

-

Marked inequalities existed between those living in the most and least deprived neighbourhoods.

Abstract

Background and aim Although national surveys are conducted of the oral health of adults in the UK, few data are available at regional and primary care trust levels to inform local commissioning. A postal survey was conducted to investigate the oral health and use of dental services by adults in the Yorkshire and Humber region.

Method A questionnaire was developed and piloted, then sent to a random sample of 25,200 adults. Data were analysed by sex, gender, age and deprivation.

Results 10,864 (43.0%) questionnaires were returned completed. Nearly three-quarters (71.6%) of respondents had 20 or more teeth and approximately one quarter (25.3%) rated their oral health as fair, poor or very poor. The percentage reporting painful aching, discomfort when eating and being self-conscious about their mouths (occasionally or more often in the last 12 months) were 28.8%, 32.8% and 29.1% respectively. Overall, 80.3% reported attending a dentist in the last two years, although nearly a quarter (22.6%) of respondents reported difficulties accessing routine care. However, there were marked inequalities between those living in the most and least deprived neighbourhoods.

Conclusion This survey was the first to investigate the oral health and service use of adults in the Yorkshire and Humber region. The findings have implications for the local commissioning of dental services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

National surveys of the oral health of adults have been undertaken every ten years in England and Wales since 1968 and in the whole of the UK since 1978.1 These surveys have provided essential information on the dental health of adults and indicated changes such as the increased retention of the natural dentition over the past four decades and the emergence of root caries as a public health problem over the same time span. As well as providing national summary statistics, data were also presented for three areas of England (Northern, Midlands and Southern). Although these data were able to indicate large geographical variations, they were of limited use at a regional or local level.

Primary care organisations (PCOs) in England and Wales are responsible for carrying out needs assessments of the communities they serve and statutory regulation requires them to undertake regular surveys of oral health to the agreed national programme.2,3 Such needs assessments are essential if PCOs' commissioning of services and oral health initiatives are to be evidence-based.4

Since 1985, UK-wide NHS surveys administered by the salaried/community dental service have been undertaken. Originally, five-year-old children were surveyed every year with older children in intervening years. In 2006, the NHS dental epidemiology programme for England decided that 2007/8 should be a 'year of innovation' with strategic health authorities (SHAs) and primary care trusts (PCTs) encouraged to undertake surveys to meet local needs. In Yorkshire and the Humber it was agreed that a survey of adults should be undertaken so that data collected might inform PCTs' commissioning decisions. The aims of the survey were to investigate the oral health and use of dental services by adults in the Yorkshire and Humber region.

Method

A postal survey of a representative sample of adults (aged 16 and over) within the Yorkshire and Humber region.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire covered self-reported oral health status, the impact of the mouth on everyday life and adults' experience of using oral health services.

Oral health status was assessed by asking participants whether they had natural teeth and, if so, how many natural teeth they had remaining. The presence of 20 or more teeth was used as an indicator of a functional dentition.1 A global single-item rating of oral health was included5 and the impact of the mouth on everyday life was assessed using three questions from the short form of the Oral Health Impact Profile.6 These three questions asked about the impact of oral health in terms of frequency of a) pain; b) discomfort when eating; and c) being self-conscious in the last 12 months.

The questionnaire also included items on patterns of dental attendance, difficulties with accessing routine and urgent care and perceived need for treatment. These questions were adapted from the interview schedule used for the national Adult Dental Health Survey in 1998.1

Piloting was undertaken in three stages, with over 50 adults from a range of ages and backgrounds. The format and wording of questions were amended on the basis of their suggestions.

Sample

Key information required by PCTs included the proportion of participants that have difficulty accessing dental services and those perceiving that they need dental care. Earlier UK studies reported 15% of adults had difficulty with access7 and 25% perceived they needed treatment.1 Based on these data, precision estimates indicated that an intended sample of 1,080 participants would provide 95% confidence that the population proportion would be 15% ± 6% (access difficulties) and 25% ± 7% (perceived need for treatment). This was regarded as acceptable for the study. To take account of non-responders, a sample of approximately 1,800 participants was drawn per PCT, making a total sample of 25,200 people from the Yorkshire and Humber region.

The accessible population included all adults (aged 16 and over) registered with a general medical practitioner and resident in a PCT within the Yorkshire and Humber region. The sampling frame was provided by NHS Connecting for Health, with the random sample drawn the day before the mailing of the questionnaires commenced.

Field work

An NHS-approved survey company (PatientPerspective) was contracted to administer the mailing, to provide interpreters and to input the data from questionnaires.

Where possible, the survey used methods identified as maximising response rates.8 Questionnaires and appropriate covering letters inviting participation were posted to selected individuals; stamped addressed envelopes were provided. Non-respondents were sent two reminders (at 3-4 week intervals). Individuals who did not wish to participate in the survey were invited to return their questionnaires uncompleted, so that they could be excluded from further mailings. The questionnaires were posted in envelopes bearing the NHS logo. The covering letter was addressed and personalised to the participant and bore the logo of the relevant PCT. Details were provided, in English and 20 other languages, of a telephone helpline (with interpreters available) for participants who needed assistance to complete the questionnaire. A dedicated email address for queries was also offered.

Weighting of data

Data were weighted before analysis for two reasons. Firstly, each PCT received the same number of questionnaires regardless of size and therefore, some PCTs were over-represented and some under-represented. Secondly, the weighting was designed to take account of variable response rates by sex, age and deprivation.

Analysis

The data were analysed by PCT and, where relevant, by sex, age and deprivation using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences and STATA. Chi squared test and Chi squared test for trends were used to investigate differences between groups and the results described are all statistically significant at the p <0.05 level. Data for the individual PCTs in the Yorkshire and Humber region will not be described in this paper, but can be found at http://www.yhpho.org.uk/resource/item.aspx?RID=10227.

Deprivation was measured based on the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2007 (IMD) score of the neighbourhood in which participants lived.9 The 'least deprived' and 'most deprived' quintiles consisted of those neighbourhoods falling among the least or most deprived 20% in England.

Ethical and research governance procedures

Ethical approval was provided by the Bradford Research Ethics Committee, which covered all 14 participating PCTs in the region. Research governance approval was sought and received from each PCT.

Results

Demographic information

Of the 25,200 questionnaires mailed, 10,864 were returned completed, a response rate of 43.1%. Higher response rates were achieved in older age groups: the response rate for those aged 16 to 34 was approximately half that of those aged 65 to 74. The response rate was generally higher in women (55.8%) than men (44.2%). There were higher response rates (49.8%) from those living in the least deprived areas compared with those living in the most deprived areas (33.9%).

Unlike age, sex and neighbourhood deprivation, there were no data on the ethnic profile of the sampling frame. However, a higher response rate from the White group appears to have been achieved compared with Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) groups based on the Office of National Statistics' (ONS) estimated ethnicity population profiles.

Oral health status

Ninety-two percent of participants had one or more natural teeth and 71.6% had 20 or more teeth; this percentage varied with sex, age and deprivation. Although the proportion of respondents who were edentulous was low, nearly 40% of participants aged 75 years and above were in this category. Overall, 21.1% and 12.1% wore an upper or a lower denture respectively, which replaced some or all of their natural teeth.

Approximately a quarter (25.3%) of adults stated that their oral health was fair, poor or very poor and this varied little by age, although it did vary according to neighbourhood deprivation: 36.3% of participants living in the most deprived quintile of England reported fair, poor or very poor oral health compared to 18.3% of those living in the least deprived quintile (Fig. 1).

Impact of the mouth on everyday life

The percentage of participants reporting painful aching in their mouths, discomfort when eating and being self-conscious about their mouths (occasionally or more often in the last 12 months) were 28.8%, 32.8% and 29.1% respectively. Although the frequency of impacts were similar for each age group, approximately 14% more participants living in areas in the most deprived quintile of England reported occasional or more frequent impacts when compared to those living in the least deprived quintile (Fig. 2).

Perceived need for dental treatment

A quarter of participants (25.4%) felt they needed dental treatment; one quarter (24.5%) did not know whether they needed treatment. More male than female participants perceived they needed dental treatment (27.5% v 23.4%). Fewer participants living in areas in the least deprived quintiles in England reported they needed treatment than those living in the most deprived areas (19.3% v 35.0%) (Fig. 3).

Time since last visit to the dentist

Overall, 80.3% of participants reported attending the dentist in the last two years, 7.5% attended between two and five years ago, 10.9% more than five years ago and 1.3% reported never attending. Of the edentate, only 32.5% reported attending in the past two years. Of the dentate, more women than men reported attending within a two-year period (81.8% v 74.0%). Attendance also varied by deprivation, with those residing in areas in the most deprived quintile being most likely to report not attending in the past two years (Fig. 4).

Reasons for visiting the dentist

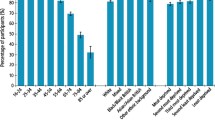

The most frequently reported reason for visiting the dentist was to have a regular check-up (68.9%), with about a fifth (19.6%) attending when they had problems and 2.7% had never been. Of the dentate, 73.0% attended for regular check-ups, with women more likely to attend than men (78.5% v 67.3%). Dentate participants in the most deprived areas were less likely to report attending for regular check-ups (Fig. 5). Edentate participants were more likely than dentate adults to attend only when having difficulties (56.0% v 16.7%), or not all (16.9% v 1.6%).

Difficulties with access to routine and emergency care

Nearly a quarter (22.6%) of all participants reported difficulties with access to routine dental care. The proportion of dentate participants reporting difficulties varied by age and sex and those in the most deprived quintile were most likely to report difficulties (Fig. 6).

Overall, fewer participants (17.8%) reported difficulties with access to care when having problems. Again this varied among the dentate by sex and age and those in the most deprived quintile were most likely to report difficulties. A similar proportion of edentate participants reported difficulty with access to routine care (19.2%) and when having problems (19.0%), but there were no trends in response by sex, age or deprivation. Of participants reporting difficulties with access to routine care and when having problems, the most frequently reported barriers were 'no dentists taking patients', 'dentists only treating privately' and 'treatment too expensive' (Table 1).

Of those reporting difficulty getting dental care when having problems, 20.0% sought help from a pharmacist, 10.2% from a doctor, 9.0% from an accident and emergency department and 13.1% from other sources (including telephone helplines, dental hospitals and family or friends).

Discussion

This paper describes the first study to investigate, in detail, the oral health and dental service use of adults in a region of the UK. The key findings of the survey are the inequalities in reported oral health status, experiences of using oral health services and demand for dental care between more and less deprived neighbourhoods.

While inequalities in health and availability of services10,11,12 and the relationship between oral health and socio-economic status1,13 have been previously described, this is the first study to use an area-based measure such as the Index of Multiple Deprivation in a survey of over 10,000 participants. The key finding has implications for PCTs in the commissioning of local services and initiatives to promote oral health. Further work is needed with PCTs to help them make optimal use of the information from the survey.

Some of the results were similar to those described in the national Adult Dental Health Survey in 1998 which was based on a clinical examination and face-to-face interview. For example, 92% of participants in the Yorkshire and Humber region had one or more natural teeth, compared to 87% of UK adults. The percentage of participants in the region reporting painful aching in the last 12 months was 28.8%, compared to 28.0% of adults in the UK. However, there was less perceived need for treatment, with approximately a quarter of participants (25.4%) expressing a need for dental treatment compared to 44% of dentate adults in the national survey. More participants (73.0%) reported regular check-ups as their reason for visiting the dentist compared with UK adults (59.0%).1 However, the impact of different methods of data collection should be considered.

For dental attendance, overall, 80.3% of participants reported attending the dentist within the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines of at least once every two years.14 However, data from the Information Centre for the same period, which are derived from FP17 forms submitted by dental practices, reported 52.9% of adults in the region had seen an NHS dentist in the 24 months before the end of March 2008.15 This finding highlights the difference between people's own perceptions of when they last attended the dentist and evidence from dental records.

Only a third (32.5%) of edentulous patients reported attending within the time period recommended by NICE. Further research is recommended to explore reasons for low utilisation of services among older people and to identify methods to encourage dental attendance. Such infrequent attendance also has implications for preventive measures such as opportunistic screening for oral cancer.

This survey in the Yorkshire and Humber region was carried out as part of the NHS dental epidemiology programme to provide PCT-level data. The need to repeat this regional postal survey in future will be reviewed in the light of feedback from PCTs on the usefulness of the information. The next national survey results are expected to be released in late 2010.

This study provides data that can be used by PCTs to inform the commissioning of dental services. Of particular value are reported reasons for difficulties accessing dental care (namely the cost of treatment and perceptions that dental practices are not accepting NHS patients) and the sources of help people rely on when they are having problems finding a dentist. While some of the PCTs in the Yorkshire and Humber region do continue to have a lack of dental capacity, others have commissioned additional services in recent years and need to ensure patients are informed how to access these services in an appropriate way. Further qualitative research is needed with members of the public about how best to communicate the cost of treatment and their preferences for information on how to find a dentist. Social marketing tools may be of use to target this information to those segments of the population who most need it.

Having employed methods identified as maximising response rates,8 43.1% of questionnaires were returned completed. The average response rate achieved by local NHS postal surveys is 45%, although a response rate of 60% is generally agreed to be acceptable due to concerns about the representativeness of the sample.16 In this study, the statistical expertise of the research team enabled the data to be weighted by sex, age and deprivation to take account of non-response bias relating to these factors. Alternative approaches to improving the response rates include using methods such as telephone administration or face-to-face interviews, however the sample sizes in such surveys are typically much lower than in this survey.

In conclusion, this postal survey of adults in the Yorkshire and Humber region revealed inequalities in oral health status, experiences of using oral health services and demand for dental care between more and less deprived neighbourhoods. This finding has implications for PCTs in the commissioning of local services and oral health promotion initiatives.

References

Kelly M, Steele J G, Nuttall N et al. Adult dental health survey: oral health in the United Kingdom 1998. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

National Health Service Wales. The Functions of Local Health Boards (Dental Public Health) (Wales) Regulations 2006. Statutory Instrument 2006 No. 487 (W.56). Cardiff: National Assembly for Wales, 2006. http://www.uk-legislation.hmso.gov.uk/legislation/wales/wsi2006/wsi_20060487_mi.pdf.

Department of Health. The Functions of Primary Care Trusts (Dental Public Health) (England) Regulations 2006. Statutory Instrument 2006 No. 185. London: The Stationery Office, 2006. http://www.opsi.gov.uk/si/si2006/20060185.htm.

Department of Health. World class commissioning website. London: HMSO, 2007. Archived online: http://collections.europarchive.org/tna/20100509080731/http://dh.gov.uk/en/Managingyourorganisation/Commissioning/Worldclasscommissioning/index.htm (accessed 13 August 2010).

Atchison K A, Gift H C . Perceived oral health in a diverse sample. Adv Dent Res 1997; 11: 272–280.

Slade G D . Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997; 25: 284–290.

Robinson P G, Nadanovsky P, Sheiham A . Can questionnaires replace clinical surveys to assess dental treatment needs of adults? J Public Health Dent 1998; 58: 250–253.

Edwards P J, Roberts I G, Clarke M J et al. Methods to increase response rates to postal questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (2): MR000008.

Department for Communities and Local Government. The English indices of deprivation 2007. London: Department for Communities and Local Government, 2008. http://communities.gov.uk/publications/communities/indiciesdeprivation07.

Black D . Inequalities in health. London: Department of Health, 1980.

Marmot M . Post-2010 strategic review of health inequalities. London: University College London, 2009.

Tudor Hart J . The inverse care law. Lancet 1971; 1(7696): 405–412.

Office for National Statistics. Children's dental health in the United Kingdom - technical report. London: Office for National Statistics, 2003.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Dental recall. Recall interval between routine dental examinations. Clinical Guideline 19. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004.

Information Centre. NHS dental statistics for England. Quarter 1: 30 June 2008. London: The Information Centre, 2008. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/statistics-and-data-collections/primary-care/dentistry/nhs-dental-statistics-q1-2008-09.

Owen-Smith V, Burgess-Allen J, Lavelle K, Wilding E . Can lifestyle surveys survive a low response rate? Public Health 2008; 12: 1382–1383.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank David Merrick for his work during the planning of this survey and Anne Cunningham, James Carpenter and Lorna Weaver for their support with the data analyses and statistics. We would also like to thank the local collaborators, Stephen Bruster of PatientPerspective, Peter G. Robinson, Pat Ludiman and Debbie Denton for their contributions to the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marshman, Z., Dyer, T., Wyborn, C. et al. The oral health of adults in Yorkshire and Humber 2008. Br Dent J 209, E9 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.819

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.819

This article is cited by

-

The oral health of adults attending dental practices in England in 2018: a report of a novel method and findings

British Dental Journal (2023)

-

Summary of: The oral health of adults in Yorkshire and Humber 2008

British Dental Journal (2010)