Key Points

-

Recognise the association of some dermatological conditions with oral and/or dental involvement.

-

Emphasises the importance of distinguishing between systemic sclerosis and linear scleroderma.

-

Stresses the importance of referring patients to the appropriate specialties when required.

Abstract

En coup de sabre is a linear scleroderma that presents on the frontal or frontoparietal scalp. This case describes a 36-year-old female who presented with a history of en coup de sabre with subsequent oral and dental involvement which to the authors' knowledge has never been reported previously. The clinical presentation, pathology and laboratory findings together with a brief discussion of the management of this case are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Clinical summary

Case report

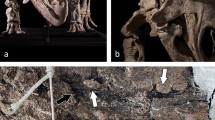

A 36-year-old female presented with gradual onset of alopecia on the scalp with subsequent painless scarring extending onto the face. This was associated with intermittent episodes of headaches which lasted for a few weeks. In July 1998, when under the care of the plastic and reconstructive surgery department, she was started on penicillamine and subsequently treated with phototherapy using ultraviolet radiation (UV) in combination with psoralens (PUVA), methotrexate and glucocorticoid injections. In December 1998, she was referred to the maxillofacial department due to extension of the condition to her oral cavity affecting the gingivae, teeth and surrounding bone. X-rays confirmed bone loss associated with the upper right central incisor in the absence of any obvious irritant cause. She was reviewed on a regular basis under the joint care of the restorative and maxillofacial surgery department. Unfortunately the medical treatment was not successful and hence in June 2000 she underwent a number of surgical procedures including excision of the linear area of morphoea on the forehead followed by tissue expansion of the scalp together with advancement of a forehead flap. Following complete burn out of the condition, there was no further hair loss and so she underwent surgical revision of the scars together with autologous fat injections to the affected areas on the forehead. Ultimately the upper central incisor was extracted and a temporary partial denture was used until a fixed prosthesis was made using the 12 and 21 as abutments to replace the missing incisor (Fig. 1).

Initial examination revealed a hypo-pigmented atrophic linear plaque approximately 6 cm wide on the right side of the forehead extending to the frontal scalp which was associated with an area of alopecia (Fig. 2). The scarring extended to the upper eyelid, medial canthus of the right eye (Fig. 3) and upper lip (Fig. 4). Eye movements were normal as was her visual acuity.

Intra-oral examination revealed scar tissue extending onto the attached gingivae associated with a mobile upper right central incisor together with marked gingival recession on the mesial aspect of 12 (Fig. 5).

Blood investigations including full blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, urinanalysis and biochemical findings of the serum were essentially normal except for a raised eosonophil and rheumatoid factor level. A computed tomogram (CT) of the head was taken which was reported as normal with no obvious underlying intra-cerebral lesions or bone loss in proximity to the skin lesion.

A biopsy from the labial gingivae in the region of the upper right central incisor was reported as showing para-keratinisation and atrophic stratified squamous epithelium occupying the mucosal surface of variably chronically inflamed collagenous connective tissue which presents with a rather hyaline appearance in places and bears resemblance to scar tissue. These changes are in keeping with morphoea.

Discussion

Localised scleroderma is the term used when the excessive deposition of collagen is localised to the skin, and possibly to the underlying muscle and tissues, as opposed to systemic sclerosis which also affects the internal organs. Onset is usually in the first two decades of life. Some authors suggest that linear scleroderma en coup de sabre occurs along Blaschko1 lines unlike this case.

Blaschko lines were believed to represent the pattern of embryonic migration of skin cells and determine the distribution of some skin diseases such as epidermal naevus, sebaceous naevi, linear lichen sclerosis, and lichen striatus. The exact cause of localised scleroderma is unknown, but localised injury, tick bites (Borelia burgdoferi),2 measles, auto-immune disorders3 and hereditary factors have been implicated.4

Morphoea is the most common type of localised scleroderma which usually presents with one or more patches of skin thickening with various degrees of pigmentation.

Linear scleroderma on the other hand presents as a band or line of skin thickening which may extend deep into the skin involving underlying muscle. The extension into the deep tissue may prevent proper joint movement and even delay growth of the underlying bones in children who are still in an active growth phase.

En coup de sabre ('cut from a sword' in French) is a deep seated form of the linear scleroderma affecting the scalp and face like a sabre cut. The hair is lost permanently and the underlying skull bones may shrink. On the rare occasion reported in this case, the supporting structures of a central incisor were also affected with consequent tooth loss. In some cases orbital involvement and hence ocular signs and symptoms may present prior to any skin lesions.5,6. Several reports of intracerebral lesions such as inflammation, calcification and demyelination were shown on MRI and CT in patients with localised scleroderma leading to epilepsy and functional motor impairments.7,8

Progressive hemifacial atrophy (Parry-Romberg Syndrome) associated with localised scleroderma has also been reported,2,9,10 but the relationship to these two conditions remains controversial. In most cases the term Parry-Romberg Syndrome should be used for progressive hemifacial atrophy alone. In such cases localised scleroderma tends to be a preceding condition to progressive hemifacial atrophy which then develops several years later.2

There is no standard modality of treatment for en coup de sabre lesions. Many drugs have been used, most with unsatisfactory results. Steroids tend to decrease the amount of collagen produced whilst the rationale for methotrexate and penicillamine is based on its potential immunosuppressive effect.11 PUVA on the other hand has both an immunosuppressive and antifibrotic effect.12 For patients with facial involvement and disfigurement, reconstructive surgery is usually an option which may vary from excision of the area with direct repair after tissue expansion to dermal grafting, all of which have been described with satisfactory results. When en coup de sabre also affects the dentition to an extent that tooth loss takes place, as with this case, referral to the restorative specialist is also required.

References

Soma Y, Fujimoto M . Frontoparietal scleroderma (en coup de sabre) following Blaschko's lines. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 38: 366–368.

Gambichler T, Kreuter A, Hoffmann K et al. Bilateral linear scleroderma 'en coup de sabre' associated with facial atrophy and neurological complications. BMC Dermatol 2001; 1: 9–11.

Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C . Rook's textbook of dermatology, 7th ed, Vol 2. pp 1334. Oxford: Blackwell, 2004.

Demir Y, Karaaslan T, Aktepe F, Yücel A, Demir S . Linear scleroderma 'en coup de sabre' of the cheek. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003; 61: 1091–1094.

Serup J, Alsbirk P H . Localised scleroderma 'en coup de sabre' and irridopalpebral atrophy at the same line. Acta Derm Venereol 1983; 63: 75–77.

Suttorp-Schulten M S, Koornneef L . Linear scleroderma associated with ptosis and motility disorders. Br J Ophthalmol 1990; 7 4: 694–695.

Stone J, Franks A J, Guthrie J A, Johnson M H . Scleroderma 'en coup de sabre'. Pathological evidence of intra-cerebral inflammation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 70: 382–385. .

Liu P, Uziel Y, Chaung S, Silverman E et al. Localised scleroderma: imaging features. Pediatr Radiol 1994; 24: 207–209. .

Tana E, Kurkcuogllu N, Atalag M, Gokoz A, Zileli T . Progressive hemi-facial atrophy with localised scleroderma. Eur Neurol 1989; 29: 15–17.

Tuffanelli D L. Localised scleroderma. Semin Cutan Med Surg 1998; 17: 27–33.

Varga J. Methotrexate shows marginal clinical efficacy in early scleroderma. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2002; 4: 97–98.

Sunderkotter C, Kuhn A, Hunzelmann N, Beissert S . Phototherapy; a promising treatment option for skin sclerosis in scleroderma. Rheumatology 2006; 45: 52–54.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pace, C., Ward, S. & Pace, A. A rare case of frontal linear scleroderma (en coup de sabre) with intra-oral and dental involvement. Br Dent J 208, 249–250 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.252

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.252

This article is cited by

-

Clinical and therapeutic course in head variants of linear morphea in adults: a retrospective review

Archives of Dermatological Research (2022)

-

Localised scleroderma en coup de sabre affecting the skin, dentition and bone tissue within craniofacial neural crest fields. Clinical and radiographic study of six patients

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2019)