Key Points

-

The provision of general smoking cessation advice to patients without acute oral complaints can be improved by more involvement of the dentist and/or task delegation.

-

Social support is important in encouraging more smoking cessation advice.

-

Implementation strategies for support of smoking cessation in dental care should focus on creating a positive advice culture among colleagues.

Abstract

Objective To investigate determinants of the provision of smoking cessation advice and counselling by various dental professionals in the dental team (dentists, dental hygienists and prevention auxiliaries). Design Cross-sectional design. Setting Sixty-two general dental practices in the Netherlands. Methods Multivariate logistic analyses of self-reported counselling behaviour collected from questionnaires for dentists (n = 72), dental hygienists (n = 31) and prevention auxiliaries (n = 50) in general dental practices. Main outcome measures Stimuli and barriers for smoking cessation counselling and advice behaviour to patients with or without oral health problems. Results Dental hygienists provided more general cessation advice and counselling than dentists. However, when patients had oral complaints, dentists counselled more often compared to prevention auxiliaries. The support from experienced colleagues positively influenced the provision of advice and counselling as well as the perceived self-efficacy for all kinds of dental professionals. Conclusions The provision of general smoking cessation advice to patients with no acute oral complaints can be improved by more involvement of the dentist and/or task delegation to prevention auxiliaries and dental hygienists. Social support is important in encouraging more smoking cessation advice and counselling. Implementation strategies for support of smoking cessation in dental care should focus on creating a positive advice culture among colleagues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smoking is one of the leading causes of illness. Professionals in public health, such as dentists and dental hygienists, can actively advise and/or support patients in their attempts to stop smoking. Various studies have addressed the dentist's role in primary and secondary prevention of tobacco dependence.1,2,3,4 Dentists and dental hygienists see their patients repeatedly over time as part of their provision of ongoing oral healthcare,1,5 thus they have ample opportunity to give advice and counselling on how to stop smoking. Studies have shown that interventions to stop smoking in dental practices are effective,3,6,7 with quit rates ranging from 16.9-18.8% compared to 4.6-7.1% in control groups. Therefore, dental guidelines recommend that dentists be involved in smoking cessation campaigns and training to involve the whole dental team.8

However, in spite of the opportunities and recommendations, the actual role of dental professionals in supporting smoking cessation is still very limited.9,10 Dentists are aware of the relation between smoking and oral health problems such as gingival inflammation.2 Nonetheless, this awareness generally does not lead to routine provision of smoking cessation advice. Only a minority of dentists (fewer than 15%) record the smoking status of their patients.4 Counselling is considered to be a greater problem than advising patients.11 The question is what actually encourages or hampers the dental team in implementing guidelines for quitting smoking in daily dental practice?

Research has identified a number of barriers to and stimuli for smoking cessation advice or counselling in daily dental practice. Gordon shows that training and supportive materials such as pamphlets can help oral health professionals to address patients' tobacco use.6 John5 found that 88% of dentists believed they should encourage their patients to stop smoking as part of their role. Different kinds of barriers were identified, eg lack of training and knowledge2,4,6,7,12,13,14,15,16 and lack of time.2,4,6,12,13,15,16,17,18 Dental professionals are also concerned with disturbing the dentist-patient relationship.4,13,14,16,17 The barriers and stimuli are summarised in Table 1.

We investigated all these stimuli and barriers at the level of the individual professional, but most dental care is given in a practice organisation with various team members. Evans mentioned the potential for delegating clinical care in general dental practice (team concept).19 Table 2 describes the members of the dental team in the Netherlands and their function in daily dental practice.

While dentists may initiate talking about smoking, dental hygienists and prevention auxiliaries could continue advising and counselling. Little is known about the influence of practice organisation and team composition on the provision of smoking cessation advice and counselling. The outcomes of this study may be relevant for identifying barriers against and stimuli for implementing smoking cessation advice and counselling in daily dental practice. Our study investigates the determinants of the provision of smoking cessation advice and counselling by various dental professionals in a team (dentists, dental hygienists and prevention auxiliaries).

Materials and methods

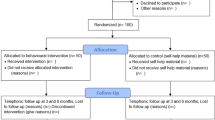

Sample

In February 2006, we recruited dental practices with the support of the Dutch Dental Association and the Dutch Association of Dental Hygienists. The convenience sample consisted of 87 practices. These practices were representative of Dutch dental practice with respect to team composition and practice size. All dental professionals received a questionnaire. Furthermore, the manager of each practice completed an organisation questionnaire (the practice manager could be one of the dentists).

Measurements

Outcomes

Advice and counselling behaviour included three types of advice and counselling.

We assessed smoking cessation advice or counselling in general with 11 items on a five-point scale asking whether the professional never (0) or always (4) paid attention to the smoking behaviour of the patient. The answers were dichotomised; the cut-off point for the delivery of advice was a median score of 12, and for counselling, a median score of 4. Factor analysis identified two factors:

-

1

The extent of focus on smoking cessation counselling in the dental practice (seven items; Cronbach's alpha = 0.83)

-

2

The extent of focus on smoking cessation advice in the dental practice (five items; Cronbach's alpha = 0.85).

We assessed smoking cessation advice or counselling for patients with oral health complaints by asking whether the dental professional never (0) or always (4) advised or counselled patients with oral health complaints about smoking. The answers were dichotomised ('never' and 'sometimes' versus 'mostly', 'often' and 'always').

We assessed smoking cessation advice or counselling for patients without oral health complaints by asking whether the dental professional never (0) or always (4) advised or counselled patients about smoking and oral health when there were no oral health complaints. The answers were dichotomised ('never' and 'sometimes' versus 'mostly', 'often' and 'always').

Determinant variables

Individual professional characteristics: Demographic characteristics include the professional's sex, age, smoking status, years of practical experience and type of professional discipline.

We assessed attitudes towards provision of smoking cessation advice and support with ten items on a five-point scale; we asked whether the professional did (4) or did not (0) associate a specific belief with delivery of smoking cessation advice and support. Factor analyses identified three attitude scales, which were interpreted as:

-

1

Fear of bothering the patient: three items (Cronbach's alpha = 0.69)

-

2

Being uncertain because of lack of knowledge about smoking cessation: four items (Cronbach's alpha = 0.81)

-

3

Doubt of feasibility in routine daily practice: three items (Cronbach's alpha = 0.79).

We assessed social support by asking the professionals to indicate whether they actually received no (0) or much (3) support for smoking cessation counselling from their assistants, their dental hygienists, other dentists, their own patients, health insurance and the Dutch Dental Association. The degree of perceived social support was expressed as a mean item score (sum score divided by the number of valid items).

We measured self-efficacy expectations with five items on a five-point scale about how confident (4) or doubtful (0) the professional felt about providing smoking cessation counselling. Factor analysis identified two self-efficacy scales, which were interpreted as (1) the degree of confidence when the patient asked for support to stop (two items; Cronbach's alpha = 0.77) and (2) the degree of confidence when the professional proactively initiated support (three items; Cronbach's alpha = 0.75).

We assessed knowledge with ten items on a four-point scale by asking whether the professional did (3) or did not (0) know the relation between an oral health disease and smoking, eg the relation between smoking and periodontal diseases, smokers' melanosis and stomatistis nicotina. We constructed a recoded score based on the quartiles (0-3) because of a skewed distribution of the sum score of the ten items.

Practice characteristics: We assessed task delegation with three items (recording the provision of advice, diagnosis and instruction; provision of information on oral health; and instruction on dental hygiene) and the division of these tasks by the various members of the team.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for socio-demographics, knowledge of the relation between smoking and oral health problems, attitudes, self-efficacy, social support, task delegation, team composition and practice organisation. Attitude and efficacy scales were constructed by means of factor analysis (maximum likelihood and oblique rotation) for the variables smoking cessation advice and counselling in general.

Bivariate correlations were expressed as Spearman's rho. Associations with smoking cessation advice and counselling related to professional type were analysed by means of logistic regression expressed as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. We used Nagelkerke R2 as indicator for the proportion of declared variance.

The statistically significant factors were subsequently put together in multivariate logistic regression models.

Results

Sample

Table 3 describes the professional and practice characteristics. All dental hygienists and prevention auxiliaries were women, and they were significantly younger than the dentists. The professional careers of the dentists had lasted longer than those of the dental hygienists and prevention auxiliaries. The dentists had doubts about the feasibility of smoking cessation counselling in their dental practices.

Smoking cessation advice and counselling

Table 4 shows how the types of advice and counselling of the various team members differed. Dental hygienists gave more smoking cessation advice in general than the dentists and prevention auxiliaries. When patients had oral health complaints, prevention auxiliaries gave less advice than the other professionals. Dentists counselled significantly more than prevention auxiliaries.

Smoking cessation advice and counselling: bivariate correlations with determinants

Table 5 presents correlations between provision of smoking cessation advice and counselling on the one hand and determinant variables on the other hand.

Professionals who perceived that they had more support from colleagues, friends and dental organisations provided more advice and counselling. Perceived self-efficacy was associated with more advice delivery in general and with more counselling when patients asked for support.

Multivariate association with smoking cessation advice and counselling (corrected for professional type)

Table 6 shows that in the multivariate analyses, the perceived social support was still significantly positively related to all types of advice and counselling in general. Male dental professionals generally counselled fewer patients than female professionals, and professionals who smoked gave significantly less cessation advice.

The team professionals differed in the types of counselling and advice: dental hygienists gave more advice to patients in general and dentists counselled more than the professionals in the other disciplines when patients had oral complaints. Prevention auxiliaries were less involved when patients had oral complaints.

Discussion

In our search for the determinants of smoking cessation advice and counselling in dental practice, we found significant differences between the members of the dental team. Dental hygienists are especially involved in delivering general advice, whereas the advisory role of the dentists was significantly greater when patients suffered from oral complaints compared to the prevention auxiliaries. Overall, perception of the support of other team members and the professional environment proved to be an important determinant for acting as an agent of lifestyle change.

Evans et al. mention the considerable scope in dental practices for task delegation.19 The outcome that dental hygienists gave significantly more advice in general confirmed our expectations, as it was in line with the difference in treatment roles between dental hygienists and other professionals. Providing lifestyle advice is part of their routine job.22 Furthermore, most of the treatment successes of the dental hygienists are more influenced by smoking than are dentist's treatments, such as chronic periodontitis.21 However, we did not expect the finding that prevention auxiliaries paid less attention to smoking cessation, especially when patients had oral health complaints, as advising patients about their lifestyle is a part of their job.

Some limitations of our study must be taken into account. The results were based on self-reported behaviour and could therefore be positively biased. Patient-reported data may show other results: previous research has shown discrepancies between answers from professionals and patients.20 We also measured practice organisation only with a task division scale; we did not consider other practice characteristics such as the appointment system, location, scale and number of team members.

Enhancing the role of hygienists and prevention auxiliaries in giving lifestyle advice could contribute to better patient outcomes. Special training for dental hygienists and prevention auxiliaries for counselling activities in the case of oral complaints may increase the success rates of stopping smoking. Further research is needed to explore how patients evaluate this task delegation in dental care.

Campbell25 shows that teamwork increases counselling and advice behaviour. Our results confirm the importance of social support from team members and professional organisations. Support from their own practice members encourages all types of professionals, as does support from dental colleagues and dental organisations. Implementation of treatment guidelines recommending the provision of lifestyle advice in routine dental care should therefore also focus on creating a supportive culture in and around the dental team.

This research was financed by an independent research grant from Pfizer.

References

Hilgers K K, Kinane D F. Smoking, periodontal disease and the role of the dental profession. Int J Dent Hyg 2004; 2: 56–63.

Chestnutt I G, Binnie V I . Smoking cessation counselling - a role for the dental profession? Br Dent J 1995; 179: 411–415.

Cohen S J, Stookey G K, Katz B P, Drook C A, Christen A G . Helping smokers quit: a randomized controlled trial with private practice dentists. J Am Dent Assoc 1989; 118: 41–45.

Gerbert B, Coates T, Zahnd E, Richard R J, Cummings S R. Dentists as smoking cessation counselors. J Am Dent Assoc 1989; 118: 29–32.

John J H, Thomas D, Richards D. Smoking cessation interventions in the Oxford region: changes in dentists' attitudes and reported practices 1996-2001. Br Dent J 2003; 195: 270–275.

Gordon J S, Lichtenstein E, Severson H H, Andrews J A. Tobacco cessation in dental settings: research findings and future directions. Drug Alcohol Rev 2006; 25: 27–37.

Albert D A, Anluwalia K P, Ward A, Sadowsky D. The use of 'academic detailing' to promote tobacco-use cessation counseling in dental offices. J Am Dent Assoc 2004; 135: 1700–1706.

Kwaliteitsinstituut voor de gezondheidszorg CBO. Richtlijn Behandeling van tabaksverslaving [Guideline for the treatment of tobacco addiction]. pp 7–171. Alphen aan den Rijn: Van Zuiden Communications BV, 2004.

Allard R H . [The practice guideline 'Treatment of tobacco addiction']. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd 2005; 112: 216–224.

Secker-Walker R H, Dana G S, Solomon L J, Flynn B S, Geller B M . The role of health professionals in a community-based program to help women quit smoking. Prev Med 2000; 30: 126–137.

Havlicek D, Stafne E, Pronk N P . Tobacco cessation interventions in dental networks: a practice-based evaluation of the impact of education on provider knowledge, referrals, and pharmacotherapy use. Prev Chronic Dis 2006; 3: A96.

Helgason A R, Lund K E, Adolfsson J, Axelsson S . Tobacco prevention in Swedish dental care. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003; 31: 378–385.

Johnson N W . The role of the dental team in tobacco cessation. Eur J Dent Educ 2004; 8(Suppl 4): 18–24.

Trotter L, Worcester P . Training for dentists in smoking cessation intervention. Aust Dent J 2003; 48: 183–189.

Watt R G, Johnson N W, Warnakulasuriya K A . Action on smoking - opportunities for the dental team. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 357–360.

Watt R G, Daly B, Kay E J . Prevention. Part 1: smoking cessation advice within the general dental practice. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 665–668.

Skegg J A . Dental programme for smoke-free promotion: attitudes and activities of dentists, hygienists, and therapists at training and 1 year later. N Z Dent J 1999; 95: 55–57.

Gorin S S, Heck J E . Meta-analysis of the efficacy of tobacco counseling by health care providers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004; 13: 2012–2022.

Evans C, Chestnutt I G, Chadwick B L . The potential for delegation of clinical care in general dental practice. Br Dent J 2007; 203: 695–699.

Rikard-Bell G, Donnelly N, Ward J . Preventive dentistry: what do Australian patients endorse and recall of smoking cessation advice by their dentists? Br Dent J 2003; 194: 159–164.

Preshaw P M, Heasman L, Stacey F, Steen N, McCracken G I, Heasman P A . The effect of quitting smoking on chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 2005; 32: 869–879.

Ohrn K . The role of dental hygienists in oral health prevention. Oral Health Prev Dent 2004; 2(Suppl 1): 277–281.

Helgason A R, Lund K E, Adolfsson J, Axelsson S . Tobacco prevention in Swedish dental care. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2003; 31: 378–385.

Halling A, Uhrbom E, Bjerner B, Solen G . Tobacco habits, attitudes and participating behavior in tobacco prevention among dental personnel in Sweden. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1995; 23: 254–255.

Campbell H S, Simpson E H, Petty T L, Jennett P A . Addressing oral disease - the case for tobacco cessation services. J Can Dent Assoc 2001; 67: 141–144.

Albert D, Ward A, Ahluwalia K, Sadowsky D . Addressing tobacco in managed care: a survey of dentists' knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Am J Public Health 2002; 92: 997–1001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rosseel, J., Jacobs, J., Hilberink, S. et al. What determines the provision of smoking cessation advice and counselling by dental care teams?. Br Dent J 206, E13 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.272

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.272

This article is cited by

-

Intention to provide tobacco cessation counseling among Indonesian dental students and association with the theory of planned behavior

BMC Oral Health (2021)

-

Assessing implementation difficulties in tobacco use prevention and cessation counselling among dental providers

Implementation Science (2011)

-

Patient awareness of oral cancer health advice in a dental access centre: a mixed methods study

British Dental Journal (2011)

-

A pilot study combining individual-based smoking cessation counseling, pharmacotherapy, and dental hygiene intervention

BMC Public Health (2010)

-

Health professional's perceptions of and potential barriers to smoking cessation care: a survey study at a dental school hospital in Japan

BMC Research Notes (2010)