Abstract

Design Two-arm cluster randomised controlled feasibility trial.

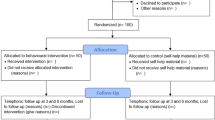

Intervention Twelve NHS dental practices were randomised to the intervention and control arms. Patients consuming alcohol above the recommended levels were eligible to participate in the trial. The intervention was delivered by the dentists in the participating practices and entailed the delivery of a short tailored alcohol-related advice tool and a leaflet, which included information about the effects of alcohol on oral health and the benefits of reducing alcohol intake to both oral and general health. Patients in the control arm were given a mouth cancer prevention leaflet only. The level of alcohol consumption was measured by validated tools (AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test and AUTID-C: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test for Consumption). The patients were followed-up after six months by a telephone interview.

Outcome Measures The feasibility trial outcomes were the recruitment, retention, eligibility and delivery rate. The primary outcome of the trial was the impact of the intervention in lowering the level of alcohol consumption as captured by the AUDIT tool. Secondary outcomes included health related quality of life and alcohol consumption and abstinence in the last 90 days. The acceptability of the intervention was also assessed.

Results The recruitment and retention rate were high (95.4% and 76.9% respectively). At the follow-up, participants in the intervention arm were significantly more likely to report a longer abstinence period (3.2 vs. 2.3 weeks respectively, P = 0.04). Non-significant differences in AUDIT (44.9% vs. 59.8% AUDIT positive respectively, P = 0.053) and AUDIT-C between baseline and follow-up (−0.67 units vs. −0.29 units respectively, P = 0.058) were observed. Results from the process evaluation indicated that the intervention and study procedures were acceptable to dentists and patients.

Conclusion According to this study, dentists offering screening for alcohol misuse and brief advice in a primary dental care setting is not only feasible but also well-welcomed by both the dental team and patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

A commentary on

Ntouva A, Porter J, Crawford M J et al.

Alcohol Screening and Brief Advice in NHS General Dental Practices: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial. Alcohol Alcoholism 2019; 54: 235-242.

GRADE rating

Commentary

Alcohol consumption above the recommended limits remains a significant public health problem in the UK. Excessive alcohol consumption has been associated with fatal accidents, accidental injuries, liver disease as well as oral and other cancers.1 A direct dose-risk relationship between alcohol consumption and oral cancer, irrespective of smoking, has been suggested in a recent systematic review.2 In recent years, there has been a call that dentists incorporate screening for common medical conditions in their consultation.3 In the UK, the Department of Health expects dentists to screen patients for alcohol misuse and offer brief advice where is deemed necessary.4

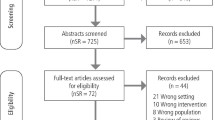

This trial was a two-arm cluster randomised controlled trial examining primarily the feasibility and acceptability of delivering alcohol screening and brief advice in an general dental practice setting. The study also aimed to assess the effectiveness of the intervention, in lowering the participants' level of alcohol consumption as measured by a self-administered questionnaire tool (AUDIT and AUTIC-C tool).

This randomised controlled trial was registered with the ISRCTN clinical trial registry and followed the research procedures as set a priori in the study protocol. The reporting of the trial followed the CONSORT guidelines. The study was conducted in a methodologically appropriate and robust manner. The randomisation was done at practice rather than patient level to avoid contamination between the trial arms. Risk of selection bias was reduced by randomising people into the group and ensuring that the groups were not aware which group they were allocated to. Although blinding of the personnel and participants was not possible , the researchers collecting the follow-up data were blinded to the participants' allocation status. Six practices were enrolled in each arm. One and two practices from the intervention and control arm respectively were lost to follow-up in six months. An equal number of patients were lost to follow-up or withdrawn from the study from each arm of the study.

The alcohol consumption screening tools used in this study have been validated in previous research and have also been endorsed by the Department of Health (UK) as tools that can be used by health care professionals to screen patients for alcohol consumption. The study was undertaken in a primary care setting involving real-life patients and the intervention was delivered by dentists during their scheduled consultation appointments which undoubtedly increases the applicability of the study.5 However, only NHS practices in North London were recruited, which may reduce the generalisability of the study, as its conclusions may not be directly applicable to other settings such as private general dental practice and community dental services settings where the working environment and conditions may differ.

Although at the follow up, participants in the intervention arm were significantly more likely to report a longer abstinence from alcohol than their peers in the control arm, the study was underpowered to detect any differences as regards to the efficacy of the intervention in helping patients to lower their level of alcohol consumption (as captured by the AUDIT and AUDIT-C tools). The authors, recognising this shortfall of the study, offer a power sample calculation for future randomised controlled trials based on the findings of their study. The acceptability of the study was evaluated by interviewing a small purposive sample of dental staff (n = 12) and participating patients (n = 14) from both the intervention and control practices. The patients who were interviewed felt that it was appropriate for the dentist to give advice on alcohol and they felt comfortable discussing the issue of alcohol consumption with their dentist which contradicts the assumptions of some dental practitioners that raising the issue of alcohol may damage their rapport with their patients.6 The dental staff found delivering the intervention overall straightforward, however, the issue of time pressures within the NHS system was raised as a potential barrier. Time pressure may hinder dentists' diagnostic performance7 which raises the question of whether the delivery of such an intervention within the current time constraints of a busy NHS practice will be feasible, but at the potential expense of other aspects of the care, for example, accurate diagnosis.

To conclude, the results of this study suggested that delivery of alcohol misuse screening and brief advice is feasible in an NHS primary dental care setting and it is welcomed by patients. Future well-powered studies with longer follow-up are warranted to assess the time that is required for the effective delivery of this intervention as well as its effectiveness in changing the patients' behaviour, habits and practices towards alcohol.

References

Room R, Babor T, Rehm J. Alcohol and public health. Lancet 2005. 365: 519-30.

Turati F, Garavello W, Tramacere I et al. A meta-analysis of alcohol drinking and oral and pharyngeal cancers: results from subgroup analyses. Alcohol Alcohol 2013 48: 107-118.

Friman G, Hultin M, Nilsson G H, Wårdh I. Medical screening in dental settings: a qualitative study of the views of authorities and organizations. BMC Res Notes 2015; 8: 580.

Department of Health. Guidance. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. 2017. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/605266/Delivering_better_oral_health.pdf (accessed August 2019).

Department of Health. Guidance. Alcohol use screening tests. 2019. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/alcohol-use-screening-tests (accessed August 2019).

Shepherd, S, Young L, Clarkson J E, Bonetti D, Ogden G R. General dental practitioner views on providing alcohol related health advice; an exploratory study. Br Dent J 2010; 208: DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.342.

Plessas A, Nasser M, Hanoch Y, O'Brien T, Bernardes Delgado M, Moles D. Impact of time pressure on dentists' diagnostic performance. J Dent 2019; 82: 38-44.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Plessas, A., Nasser, M. Can we deliver effective alcohol-related brief advice in general dental practice? . Evid Based Dent 20, 77–78 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-019-0036-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-019-0036-3