Abstract

Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma (SSEH) is a rare cause of spinal cord compression. Symptoms may include sudden-onset axial pain followed by neurologic involvement including weakness, numbness and incontinence. Here we report the case of a patient followed prospectively after surgical intervention following SSEH and recovery following inpatient rehabilitation. This patient presented with right hemiplegia, neurogenic bladder and bowel with autonomic dysfunction. the patient with significant gains in Functional Independence Measure scale that improved from 15 on admission to 35 1 month following surgery. This case suggests that treating this type of patients requires hospitals specialized in spinal cord injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma (SSEH) is a rare condition that is characterized by the symptoms of spinal cord compression. Symptoms may vary clinically from radicular symptoms to quadriplegia depending on the extent of cord compression.1 Etiologies that have been reported include anticoagulant use, vascular malformations, coagulopathies, infections and disk herniation. Available data suggest that emergent surgical treatment is indicated for improved neurological outcomes.2 As more studies have been reported regarding SSEH, it must be included in the differential diagnosis of acute-onset axial pain with such neurological findings. Magnetic resonance imaging has been reported as the first diagnostic tool for evaluation.3 However, limited data exist regarding multilevel SSEH rehabilitation.4 The following case explores recovery following surgical intervention for multilevel SSEH and the importance of inpatient rehabilitation following this condition.

Case report

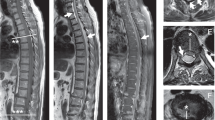

The case of an 82-year-old male patient with a history of atrial fibrillation diagnosed 10 years ago and treated with warfarin who suddenly started experiencing sudden neck pain is reported here (Figure 1). Four hours after the onset of symptoms, the patient was admitted to the ER. The pain progressively worsened during the day; the patient referred no associated trauma and denied any signs or symptoms of spinal cord etiology. Five hours after the onset of symptoms, cervical X-ray scans were done, which proved negative, and the patient was discharged with pain management medication 5 hours later. Eight hours after discharge, he developed sudden-onset right hemiplegia and was taken again to the hospital. Due to initial suspicion of stroke, the patient was re-admitted to the ER for further workup. CT imaging of the head and neck was done at 2 hours after re-admission, which revealed no abnormalities. Two days after re-admission, the patient developed urinary dysfunction requiring an indwelling foley catheter; INR taken at the time showed a level of 5.2. Neck magnetic resonance imaging done 1 day later showed C3-T1 epidural hematoma, and decompressive laminectomy was performed 3 days later by Neurosurgery Service. Seven days later, the patient was admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation program, where he was evaluated using the Functional Independence Measure (FIM)5 scale. After 30 days, the patient completed the rehabilitation program and was discharged from inpatient rehabilitation services. A timetable summarizing the patient’s history is presented in Table 1.

Discussion

SSEH is an unusual phenomenon that can present with symptoms of spinal cord compression such as neck or back pain and sudden onset of neurologic deficits localized to the level of compression. Neurologic deficits include sensory and motor deficits occasionally accompanied by neurogenic bowel or bladder. Paresis is commonly bilateral and seldom unilateral.2 Etiologies include blood coagulopathies, anticoagulant treatment, infection, tumorigenesis, pregnancy, herniated discs, Paget’s disease and vascular malformations.6 Although clinical presentation and neurologic examination are important, imaging studies of the SSEH are the most reliable diagnostic tool,2 magnetic resonance imaging being the test of choice. It provides information about the nature and extent of the hematoma, as well as the degree of cord compression.3 This case is rare and occurs because of the sudden onset of right hemiplegia, as experienced by this patient, and the multilevel involvement shown on magnetic resonance imaging. Scarce data exist regarding the percentage of patients with unilateral symptoms, and previous studies report hematomas that cover three or more vertebra 50% of the time.7

Our patient was on chronic anticoagulant therapy due to atrial fibrillation since diagnosis 10 years ago. Anticoagulants are a known risk factor for intracranial and intraspinal bleeding.8 It was reported that 25–70% of patients with SSEH are treated with such medications.9 Anticoagulant therapy should be discontinued in this type of patient when presenting with neurologic symptoms. Although the interval for observation of patients for postoperative recurrence of epidural hematoma and the optimal time for resumption of warfarin therapy is not precisely known, it can be expected that a period of several days to 1 week is necessary to obtain stable hemostasis in the spinal surgical area.9

Available data suggest that emergent surgical treatment is indicated for improved neurological outcomes.4,8 It was reported that the neurologic recovery after surgery varies with the severity of the preoperative impairment, and the time elapsed between initial symptoms and surgical intervention.10 Because there is a tendency for neurologic progression, most patients are treated with prompt decompressive surgery within 36 h.10 There have also been reported significantly better outcomes for patients with complete neurologic deficit that underwent decompression within 36 h of symptom onset11 and within 48 h in patients with incomplete deficit.6 These data suggest that early diagnosis and prompt surgical decompression are the key for improved neurological recovery.12–17

Although there are extensive data published about the relationship between prompt surgical decompression and neurological outcomes, there are no data on recovery following inpatient rehabilitation. Our patient underwent surgical decompression 4 days after onset of neurological symptoms and was admitted to the rehabilitation unit 7 days after the operation. Table 2 demonstrates improved muscle strength scores following surgical decompression using the International Standards for Classification of Spinal Cord Injury as a reference. In this case, after 3 weeks of treatment in the rehabilitation unit, the patient experienced significant improvement in muscle strength. Furthermore, as noted by FIM scores (motor item), the patient showed significant improvement specifically in transfers and mobility, as evidenced by the change in total motor score from admission (18) to discharge (36), with an overall improvement of 18 total points (Table 3).

These data imply that physical therapy and rehabilitation medicine can significantly improve physical neurologic function, as well as FIM measures of patients after SSEH. Future research may be directed at recognizing and studying the importance of early rehabilitation in SSEH.

Conclusion

Spontaneous epidural hematoma is a rare disorder that can present as an acute spinal cord clinically and can be misdiagnosed. As in our case, multilevel spinal cord compression secondary to hematoma after prompt surgical intervention can benefit from inpatient rehabilitation that specializes in spinal cord injury. This may lead to significant improvement in functional outcomes.

References

Horcajadas A, Katati M, Arraez MA, Ros B, Abdullah O, Castañeda M et al. Spontaneous epidural spinal hematoma: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Neurologia 1998; 13: 401–404.

Adamson DC, Bulsara, Brone PR . Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma: case report and literature review. Sirg Neurol 2004; 62: 156–159.

Matsumura A, Namikawa T, Hashimoto, Okamoto T, Yanagida I, Hoshi M et al. Clinical management for spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: diagnosis and treatment. Spine J 2008; 8: 534–537.

Grollmus J, Hoff J . Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: good results after early treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1975; 38: 89–90.

Awang H, Ekangaki A, Poulos R, Dickson H, Kohler F . Understanding the functional independence measure: a study of rehabilitation inpatients. J Med Sci 2001; 1: 30–33.

Kim JK, Kim TH, Park SK, Hwang YS, Shin HS, Shin JJ . Acute spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma mimicking cerebral stroke: a case report and literature review. Korean J Spine 2013; 10: 170–173.

Lobitz B, Grate I . Acute epidural hematoma of the cervical spine: an unusual cause of neck pain. South Med J 1995; 88: 580–582.

Choi JH, Kim JS, Lee SH . Cervical spinal epidural hematoma following cervical posterior laminoforaminotomy. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2013; 53: 125–128.

Kiralzi Y, Akkoc Y, Kanyilmaz S . Spinal epidural hematoma associated with oral anticoagulation therapy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 83: 220–223.

Fukui MB, Swarnkar AS, Williams RL . Acute spinal epidural hematomas. Am J Neuroradiol 1999; 20: 1365–1372.

Alexiadou-Rudolf C, Ernestus RI, Nanassis K, Lanfermann H, Klug N . Acute nontraumatic spinal epidural hematomas: an important differential diagnosis in spinal emergencies. Spine 1998; 23: 1810–1813.

Rodriguez-Quinonez A, Schneck MJ, Biller J . Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma as a complication of oral anticoagulation therapy. Semin Cerebrovasc Dis Stroke 2004; 4: 226–229.

Halim TA, Nigam V, Tandon V . Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma: report of a case managed conservatively. Indian J Orthop 2008; 42: 357–359.

Hsieh CF, Lin HJ, Chen KT, Foo NP, Te AL . Acute spontaneous cervical spinal epidural hematoma with hemiparesis as the initial presentation. Eur J Emerg Med 2006; 13: 36–38.

Groen RJ, van Alphen HA . Operative treatment of spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas: a study of the factors determining postoperative outcome. Neurosurgery 1996; 39: 494–508.

Foo D, Rossier AB . Preoperative neurological status in predicting outcome of spinal epidural hematomas. Surg Neurol 1981; 15: 389–401.

Chang FC, Liring JF, Chen SS, Luo CB, Guo WY, Teng MM et al. Contrast enhancement patterns of acute spinal epidural hematomas: a report of two cases. Am J Neuroradiol 2003; 24: 360–366.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perez, J., Crespo, M., Velez, C. et al. Inpatient rehabilitation following operative spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma mimicking stroke: a case report. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 2, 16007 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2016.7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2016.7

This article is cited by

-

Acute spontaneous thoracic epidural hematoma, triggered by weight-lifting training, in a retired sportsman: case report and literature review

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2017)