Abstract

Study design:

A case report of staphylococcal transverse myelitis.

Objectives:

To illustrate the clinical presentation of acute transverse myelitis due to Staphylococcus aureus, without a contiguous source of infection.

Setting:

National Neuroscience Institute.

Case report:

A 79-year-old female was diagnosed with acute transverse myelitis. Clues to an infectious etiology included fever, raised inflammatory markers and cerebrospinal fluid neutrophilic pleocytosis. Staphylococcal etiology was established based on cerebrospinal fluid and blood cultures. Despite extensive investigations, no contiguous or systemic source of infection could be identified. She was treated with appropriate antibiotics; however, neurological recovery was poor.

Conclusions:

Bacterial myelitis may occur in isolation and the diagnosis should not be discounted when evaluation shows an absence of a contiguous or systemic source of infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute transverse myelitis (ATM) encompasses a heterogeneous group of autoimmune demyelinating, inflammatory or infectious disorders.1 Infectious causes of myelitis can be viral, bacterial, fungal and rarely parasitic.1 Bacterial myelitis or spinal cord abscess has been postulated to occur via hematogenous spread.2, 3 Kastenbauer et al.4 separately described acute spinal cord dysfunction, including myelitis, during the course of bacterial meningitis. We report a rare case of isolated Staphylococcus aureus myelitis, wherein differentiation from transverse myelitis is critical for therapeutic decision-making.

Case report

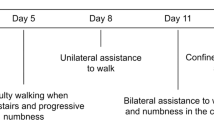

A 79-year-old immunocompetent female presented with 2 days of fever and acute-onset bilateral lower limb weakness upon awakening. She was last seen ambulating independently the night before. There was no history of back trauma, pain or meningismus. She had well-controlled diabetes mellitus (HbA1c 6.3%), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cervical spondylosis and ischemic heart disease. She was febrile (temperature 38 °C) and general physical, cardiovascular and respiratory examinations were normal. Neurological examination revealed flaccid paraplegia with acute urinary retention, absent lower limb deep tendon reflexes, flexor plantar responses and normal anal tone and lower limb sensory function.

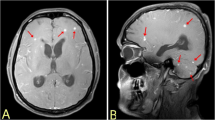

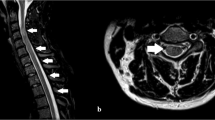

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine showed a non-enhancing T2-weighted hyperintense intramedullary lesion at T11 (Figure 1). An enhancing L1 vertebral body lesion was noted; this was evident on MRI 1 year previously, with stable characteristics. Brain MRI was unremarkable. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed neutrophilic pleocytosis, raised proteins and normal glucose. Systemic inflammatory markers were raised, autoimmune work-up was negative (Table 1) and chest X-ray was normal. HIV serology was not performed. Treatment for transverse myelitis was initiated with intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone, concurrently with IV ceftriaxone (1 g daily).

Subsequently, blood and CSF culture yielded methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) 2 days later. Methylprednisolone was stopped; antibiotics were modified to IV crystalline penicillin (4 megaunits 4 hourly) based on culture sensitivity. Further investigations were performed to localize the source of infection. Abdomen computed tomography (CT) was normal; chest CT showed lower lobe atelectasis. As she did not have respiratory symptoms or productive cough before presentation, as well as during hospital stay, no other respiratory investigations were performed. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed thickened mitral valve and aortic sclerosis, with no vegetations; the patient declined trans-esophageal echocardiogram. Bone scintigraphy showed focal increased radiotracer uptake at T10/11 vertebrae, indicative of abnormal osteoblastic reaction; spine MRI did not reveal any corresponding changes in this area. Patient did not improve neurologically after 6 weeks of antibiotic treatment and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Myelitis describes inflammation of the spinal cord, and may be secondary to a wide range of conditions. ATM incidence is estimated to be 1.34–4.6 per million.1 Inflammatory etiologies of ATM are the commonest, with corticosteroids used as first-line treatment. Whereas inflammatory ATM has well-defined diagnostic criteria, it may be difficult to differentiate from infectious myelitis.1

Infectious myelitis commonly affects the thoracic cord, and presents with fever and paraparesis. Symptoms evolve over hours to days.5 Additional clinical features, such as fever, meningismus, rash, concurrent systemic infection, an immunocompromised state, a history of recent travel, recurrent genital infection and radicular burning pain, may suggest specific infectious etiologies.1 Etiological agents include viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites. Bacterial myelitis or spinal cord abscess has been postulated to occur from hematogenous spread of a contiguous focus in the spine or secondary to bacteremia arising from a distant source.2, 3 Kastenbauer et al.4 described acute spinal cord dysfunction during the course of bacterial meningitis and postulated venous congestion, ischemic infarction or myelitis as possible mechanisms.

Our patient presented with ATM and initially, it was difficult to distinguish between infectious myelitis and inflammatory ATM. Spine MRI was not helpful in establishing the diagnosis as the features were not diagnostic for either condition.2, 3 Fever, raised inflammatory markers, and systemic and CSF neutrophilic response guided the initial decision to treat with both antibiotics and corticosteroids. Our patient was subsequently diagnosed with MSSA myelitis proven on blood and CSF culture. Extensive investigations did not reveal evidence of cranial meningitis or contiguous MSSA infection in the spine or from a distant source. Bone scintigraphy showed vertebral osteoblastic changes. However, in the absence of corresponding MRI abnormalities, such changes are nonspecific and are unlikely to be indicative of osteomyelitis.

Bacterial myelitis is often not suspected on presentation as inflammatory ATM is relatively more common. Infectious myelitis are most commonly caused by viruses.1 It is important to identify the etiology of infectious myelitis as they are treatable. In our patient, CSF neutrophilic pleocytosis and raised systemic inflammatory markers were clues to a bacterial myelitis. In addition, our patient demonstrated that bacterial myelitis may occur in isolation and the diagnosis should not be discounted when spinal imaging shows an absence of a contiguous source of infection.

References

West TW, Hess C, Cree BAC . Acute transverse myelitis: demyelinating, inflammatory, and infectious myelopathies. Semin Neurol 2012; 32: 97–113.

Friess HM, Wasenko JJ . MR of staphylococcal myelitis of the cervical spinal cord. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1997; 18: 455–458.

Murphy KJ, Brunberg JA, Quint DJ, Kazanjian PH . Spinal cord infection: myelitis and abscess formation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1998; 19: 341–348.

Kastenbauer S, Winkler F, Fesl G, Schiel X, Ostermann H, Yousry TA et al. Acute severe spinal cord dysfunction in bacterial meningitis in adults: MRI findings suggest extensive myelitis. Arch Neurol 2001; 58: 806–810.

Roos KL . Acute severe spinal cord dysfunction in bacterial meningitis in adults: MRI findings suggest extensive myelitis. Arch Neurol 2001; 58: 717–718.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saini, M., Prasad, K., Ling, L. et al. Transverse myelitis due to Staphylococcus aureus may occur without contiguous spread. Spinal Cord 52 (Suppl 2), S1–S2 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.69

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.69