Abstract

Study design:

Single case report.

Objective:

We present a case of paraplegia due to neuromyelitis optica (NMO) with poor rehabilitation outcome.

Setting:

University hospital, Japan.

Case report:

A 27-year-old woman with NMO presented with T5 paraplegia of ASIA impairment scale grade A. Spinal cord magnetic resonance imaging revealed a lesion spanning C3 to L1 level. After acute phase treatment, flaccid paraplegia below T5 and a T2-weighted hyperintense lesion from T6 to T10 level remained. Rehabilitation aimed at independence of activities of daily living with wheelchair assistance, including transfer activity, was provided for 19 months. However, flaccid paralysis of the trunk and limbs persisted, and safe independent transfer was not achieved.

Conclusion:

Spinal lesions spanning many vertebral segments, a characteristic of NMO, can cause extensive flaccid paralysis of the trunk and limbs. Rehabilitation may achieve poorer functional recovery than that for spinal cord injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is an inflammatory disorder characterized by acute optic neuritis and extensive transverse myelitis spanning more than three vertebral segments.1, 2 It was once considered a subtype of multiple sclerosis (MS), but identification of the NMO-specific antibody anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP-4) distinguished the two etiologically.1, 3 Furthermore, spinal cord lesions observed in NMO involve many vertebral segments and are associated with grey matter necrosis, whereas those observed in MS span less than one vertebral segment.1 There are many reports on rehabilitation for MS, but few on that for NMO. We report a case of paraplegia caused by NMO affecting a large spinal cord span that did not achieve wheelchair transfer activity.

Case report

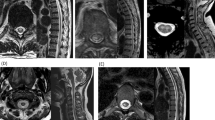

A 27-year-old woman, presented with intra-uterine fetal death at 39 weeks. A few days after fetus removal, she presented with fever, muscle weakness of lower extremities and urinary retention. During the next few days, she became completely paraplegic. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a T2-weighted hyperintense lesion in the central spinal cord from C3 to L1 level (Figure 1). Serum was positive for anti-AQP4 antibody, confirming NMO. Paraplegia persisted after acute phase treatment, and she was admitted to a rehabilitation department 3 months after onset. According to the criteria of ASIA impairment scale, flaccid paraplegia below T5, muscle weakness of lower limbs (manual muscle test score of 0), hypoesthesia from T5 to T6 and anesthesia below T7 were detected on admission. We estimated her impairment as ASIA impairment scale grade A. Static and dynamic sitting balance was unstable. There were no abnormalities in visual acuity or field dimensions. Therefore, it should be better to make a diagnosis of NMO spectrum disorder by considering the absence of visual problems and a positive test for anti-AQP4 antibody. Spinal cord MRI revealed a T2-weighted hyperintense lesion from T6 to T10 level (Figure 2). The extent of involvement was similar in a subsequent scan taken 6 months after onset. The main goal of rehabilitation was independence of activities of daily living (ADL) using a wheelchair. During in-patient rehabilitation, NMO did not relapse, allowing uninterrupted therapy. However, the state of paralysis did not improve, and sitting balance remained poor. Moreover, urinary retention did not ameliorate, resulting in the need for autocatheterization. She achieved push-up activity but had difficulty in transfer activity. She finally achieved independent transfer between a bed and a wheelchair using a transfer board, but she needed assistance in other situations (Table 1). She was discharged and returned home 7 months after onset. Although she continued outpatient rehabilitation for 1 year, there was no significant improvement in transfer activity.

Discussion

It is possible to achieve independent transfer activity in cases of spinal cord injury (SCI) sparing spinal segment C7. Although this case’s residual spinal segment was T5, transfer activity remained difficult, underscoring the differences in spinal pathophysiology and outcome between SCI and NMO. In NMO, the spinal cord lesion is continuous for at least three vertebral segments and transverse myelitis affects grey matter.3, 4 Pathologically, demyelination and necrotic lesions are widespread.3, 4 Therefore, the anterior horn is damaged and neuronopathy occurs.5 The dysfunction in NMO is more severe than that in MS because of the severe disorganization and greater extent of the lesion.2, 4 This case presented with an extensive MRI lesion spanning most of the spinal cord in the acute phase and from T6 to T10 level in the chronic phase. Although the residual spinal segment determined by clinical findings on admission was T5, disorganization of grey matter may spread below T6 level. In contrast, most SCIs are focal, and motor neurons remain viable below the lesion. Spasticity gradually appears in SCI, which can improve the support of the trunk and limbs during movement. In this case of NMO, however, because of the severe myelitis that presents severe disorganization and affects the gray matter, and the involvement of many vertebral segments, it is likely that motor neurons were damaged below the lesion, and spasticity did not appear. Thus, flaccid paralysis of the trunk and lower limbs persisted, contributing to instability of the trunk and lower limbs, and making transfer activity difficult.

Conclusion

We describe a case of paraplegia due to NMO that could not achieve independent transfer activity. This may result from transverse myelitis involving many vertebral segments and severe spinal disorganization, which are characteristic of NMO. Achieving independent ADL may be more difficult in cases of paraplegia due to NMO than for other SCIs.

References

Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG . The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol 2007; 6: 805–815.

Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG . Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2006; 66: 1485–1489.

Oh J, Levy M . Neuromyelitis optica: an antibody-mediated disorder of the central nervous system. Neurol Res Int 2012; 2012: 460825.

Misu T, Fujihara K, Kakita A, Konno H, Nakamura M, Watanabe S et al. Loss of aquaporin 4 in lesions of neuromyelitis optica: distinction from multiple sclerosis. Brain 2007; 130: 1224–1234.

Pessoa FM, Lopes FC, Costa JV, Leon SV, Domingues RC, Gasparetto EL . The cervical spinal cord in neuromyelitis optica patients: a comparative study with multiple sclerosis using diffusion tensor imaging. Eur Radiol 2012; 81: 2697–2701.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, M., Sugiyama, K., Kondo, T. et al. Rehabilitation for paraplegia caused by neuromyelitis optica: a case report. Spinal Cord 52 (Suppl 3), S14–S15 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.139

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.139

This article is cited by

-

Symptomatic and restorative therapies in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders

Journal of Neurology (2022)