Abstract

Study design:

Administration of the walking index for SCI (WISCI) II is recommended to assess walking in spinal cord injury (SCI) patients. Determining the reliability and reproducibility of the WISCI II in acute SCI would be invaluable.

Objectives:

The objective of this study is to assess the reliability and reproducibility of the WISCI II in patients with traumatic, acute SCI.

Design:

Test–retest analysis and calculation of reliability and smallest real difference (SRD).

Setting:

SCI unit of a rehabilitation hospital.

Methods:

Thirty-three patients, median age 44 years, median time since onset of SCI 40 days. Level: 20 cervical, 8 thoracic, 5 lumbar; ASIA (American Spinal Injury Association) impairment scale (AIS) grade: 32 D/1 C. Assessment of maximum WISCI II levels by two trained, blinded raters to evaluate interrater (IRR) and intrarater reliability.

Results:

The intrarater reliability was 0.999 for therapists A and 0.979 for therapists B, for the maximum WISCI II level. The IRR for the maximum WISCI II score was 0.996 on day 1 and 0.975 on day 2. The SRD for the maximum WISCI II score was 1.147 for tetraplegics and 1.682 for paraplegics. These results suggest that a change of two WISCI II levels could be considered real.

Conclusions:

The WISCI II has high IRR and intrarater reliability and good reproducibility in the acute and subacute phase when administered by trained raters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Valid and reliable outcome measures in clinical trials on spinal cord injuries (SCIs) must be generated to develop effective treatment interventions—a necessity that is particularly true for walking function, which is a principal goal for subjects with SCIs.1 Thus, it is conceivable that many clinical trials will be geared toward walking recovery and require valid outcome measures. Outcome measures that are related to walking function include measures of walking capacity, such as short-distance timed walk, long distance (6-min walk) and the walking index for SCI (WISCI II).

The WISCI was introduced in 20002 and modified in 2001 (WISCI II)3 as a measure of the capacity to walk for use in clinical trials, incorporating the use of walking aids, braces and physical assistance on a 21-point scale. The WISCI was ranked by an international group of SCI clinicians and investigators from most impaired to least impaired, and has demonstrated theoretical construct and face validity. It was subsequently compared with four scales in a clinical population of mixed SCI and spinal cord lesions to validate its retrospective criteria (versus other scales).4

In 2006, the WISCI was used in a multicenter, randomized clinical trial, as assessed by blinded observers, and correlated well with lower extremity motor score, balance, walking speed, 6-min walking distance and locomotor functional independence measure score, validating its prospective criteria.5 Since then, the WISCI II has enjoyed increased popularity and acceptance.6

A recently published systematic search of the literature on WISCI/WISCI II (2013)7 clarified its use and further needs. Although the review concluded that its validity is well established, it summarized the responses to suggestions for additional examination of its reliability, pointing out that the initial assessment of the reliability of the WISCI (2000)2 dealt with agreement among experts from eight countries with regard to the correct ranking of WISCI levels by video images. Further, the review concluded that a more ‘crucial test’ of a measure of capacity requires test–retest assessment of patients following SCI by trained raters. Although Marino et al.8 and Burns et al.9 fulfilled such a test in chronic subjects, only Scivoletto et al.10 have studied this issue in acute subjects in a preliminary report of 19 subjects.

For these reasons, this study was performed to demonstrate the interrater (IRR) and intrarater reliability of the WISCI II at maximum levels in patients with acute SCIs.

In addition, we examined the true difference (smallest real difference, SRD) in acute SCI subjects. The SRD is a measure of test–retest reliability and within-subject variance.8 The SRD is a measure of the noise. Following an intervention, a change in score would need to exceed the SRD to be considered ‘real.’

Patients and methods

Subjects

Study subjects were recruited from the Spinal Unit, IRCCS S. Lucia, Rome, Italy. Candidates must have sustained a traumatic SCI within 3 months (acute lesions per other studies5). Inclusion criteria included a history of traumatic SCI, incomplete motor status (American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) impairment scale (AIS) C or D) and a motor level of C4–L1 inclusive per the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI).11 Neurological status was confirmed by examination before testing the WISCI II level. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was conducted as per the Declaration of Helsinki.

Assessments

The neurological status was assessed by SCI physicians and trained physical therapists as per the ISNCSCI.11 The key upper and lower limb muscles were graded by manual muscle testing on a six-point scale for each limb, and the AIS grade was determined for each subject.

As recommended for reliability studies,12 the WISCI II was assessed by physical therapists who were trained on the use of the WISCI II, and instructed with regard to testing for IRR and intrarater reliability. Two therapists, A and B, tested subjects on 2 different days (within 48/72 h) for the maximum WISCI II levels as per the following protocol. We chose a shorter time than recommended,12 because the patients were in the acute/subacute phase, and therefore changes in strength and function may occur in days rather than weeks.13

Maximum level was defined as the level that was (1) safe during training in therapy compared with a hospital environment, (2) for a 10-m distance, and (3) judged to be safe by the training therapist. Thus, we adopted a more rigorous definition of ‘safe’ than what is applied to a chronic subject. ‘Safe’ was defined as having adequate balance to prevent falling, clear and place the foot flat on the surface, cause minimal lurching, and affect upright posture.8, 9 Attaining ‘safe’ might have required physical assistance, the use of braces and other supports, and appropriate walking aids.

The maximum capacity of WISCI II levels was determined as follows:

-

1

Therapist A determined the maximum WISCI II level for each individual at the time of early mobilization following injury during inpatient hospitalization. The therapist confirmed that the subject could safely ambulate at this level by observation; then, the maximum WISCI II level was recorded by the same therapist.

-

2

Therapist B obtained the same history from subject 1 and tested him on the same day as per the protocol above. Therapist B was blinded to the evaluation by therapist A, which meant that neither therapist was present for or discussed his colleague’s evaluation.

-

3

Therapist B repeated the protocol for subject 1 in 48/72 h, after which therapist A did so. The therapist who last evaluated the subject on the first day evaluated him first on the second day.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 12.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables as median and interquartile range and full range. IRRs and intrarater reliabilities were determined for maximum WISCI II levels using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and a one-way, random effects model.9

Reproducibility of the WISCI II scale was assessed by calculating the SRD.8, 9, 14 As reported by Marino et al.8 and Burns et al.,9 ‘the SRD is a function of the standard error of measurment (s.e.m.) that assesses the test–retest reproducibility of a measure by calculating the variability of measurements in the same individual.14 The s.e.m. is the square root of the within-participant variance. The SRD was calculated as SRD95=s.e.m. × √2 × 1.96.

Results

Our study group comprised 33 patients (28 males and 5 females), with a median age of 44 years (interquartile range 28 and full range 69); the median time since onset of SCI was 40 days (interquartile range 32 and full range 73). With regard to lesion level, 20 patients had a lesion at the cervical level versus 8 at the thoracic level and 5 at the lumbar level. All patients but one were AIS grade D; and one patient was classified as AIS grade C and had a lesion at the lumbar level (Table 1).

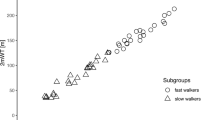

The ICCs for intrarater reliability were 0.999 for the maximum WISCI II score for therapist A and 0.979 for therapist B (Table 2). The IRR reliability for the maximum WISCI II score was 0.996 on day 1 compared with 0.975 on day 2 (Table 2). These values were comparable when subjects with paraplegia and tetraplegia were examined separately (Table 2). Raters differed in maximum WISCI II evaluation for seven subjects (nos. 5, 13, 16, 17, 19, 25 and 29; Table 1).

The reproducibility of the WISCI II was supported by the SRD (Table 3). The SRD was 0.883 for the maximum WISCI II score, and 1.112 and 1.212 for subjects with tetraplegia and paraplegia, respectively.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the reliability and reproducibility of the highest WISCI II level in patients with acute SCI. Although the WISCI is a relatively simple measure and detailed instructions exist on how to evaluate and progress, the patients along the various levels (http://www.spinalcordcenter.org/research/wisci_guide.pdf), we decided to undertake this study based on two evidences. First, acute SCI patients are different from chronic ones because, in particular incomplete patients, they exhibit a rapid motor recovery as demonstrated in a number of studies.13, 15, 16, 17 Second, acute SCI patients show fluctuations of their clinical status due to factors such as fatigue, psychological distress and so on. They may also be more difficult to evaluate, especially for the issue of safety. As a consequence, in our previous pilot study on the IRR and intrarater reliability of acute subjects,10 4 of 21 (19%) subjects showed a difference in maximum WISCI level in at least one of the four assessments. However, Burns et al.9 reported that in chronic subjects, the assessment of maximum WISCI II level by the two examiners differed in two of 63 (3%) cases, with higher reliability coefficients than those reported in our study. Therefore, according to previous studies18, 19 that state that measurement errors, and thus the reliability of a measure, are not a fixed property but are dependent on the studied population, in the effort of improving the generalizability of the WISCI II, we decided to enlarge our pilot study on acute SCI patients.

The rationale for examining the highest WISCI II level has been presented by several studies of chronic patients.8, 9, 20

Reliability and responsiveness

The reliability of the WISCI was established in its development when a videotape of patients who were walking at each level (40 randomized clips) was circulated to SCI experts. The IRR was 1.00 across 24 individual participants and 8 participating teams.2 However, the assessment of reliability at that stage required consensus on the number and types of aids and assistants with which the person was walking; further, there are claims that further evidence of reliability and responsiveness is needed.15, 20, 21, 22

Nevertheless, reliability studies on the WISCI are available only in chronic SCI patients.8, 9 Recently, Marino et al.8 reported that for chronic SCI patients, the IRR and intrarater reliability was 1.00 for SS WISCI II. The intrarater reliability for maximum WISCI II level was 1.00 and IRR reliability was 0.98. The progression from self-selected to maximum WISCI II level also showed high agreement between and within therapists. In another study of 76 subjects with chronic SCI, Burns et al.9 reported excellent reproducibility of the WISCI II.

Although Burns et al.9 states that ‘in participants with acute SCI, validity and reliability have been demonstrated for both timed walking tests (for example, 10 and 6 min walk test) and categorical scales (for example, WISCI II)9’ with multiple references, this requires clarification. The studies cited for the WISCI only relate to validity, while reliabity only relates to the timed walking.

With regard to acute SCI, Van Hedel et al.23 studied the walking ability of a small cohort of patients (N=22) with acute SCI using several walking measures (timed up and go; 10 and 6 min walk test), but he assessed the IRR and intrarater reliability only for the timed tests. Although he used the WISCI to validate these measures in the same report,15 he did not perform reliability studies of the WISCI.

In this study, we have demonstrated the IRR and intrarater reliability of the maximum WISCI II level in patients with acute SCI, which was excellent (0.975–0.999). Test–retest reliability indicates the level of measurement error, or ‘noise,’ for an outcome measure—that is, how similar the values are when measuring an unchanged parameter on more than one occasion. Increased reliability makes it easier to differentiate real change from noise.

Reproducibility

The reproducibility of an instrument is an index of the precision of single measurements and is a function of its test–retest reliability. Better reproducibility implies greater precision, whereas high variability is associated with poor reproducibility. In this case, a larger difference is needed to detect a real change. SRD is an estimate of the smallest change in a score that can be detected objectively for a client—that is, the amount by which a patient’s score needs to change to ensure that the change is greater than the measurement error. SRD can be used as an indirect measure of the responsiveness of outcome measures. Only one study has assessed the SRD of the WISCI II in chronic SCI—Burns et al.9 reported an SRD for the maximum WISCI II level of 0.597 and concluded that a change of one WISCI II level in a chronic patient can be interpreted as real.

In our study, the significant real difference of 1.147 (tetraplegics) and 1.682 (paraplegics) for the maximum WISCI II level suggests that in acute SCI patients, an increase in the WISCI II must be at least two levels to be considered a true improvement. The difference between our study and the report by Burns’s et al.9 is that in the latter, the assessment of maximum WISCI II level by the two examiners differed in 2 of 63 cases, with a low within-subjects s.d. However, in our study, the evaluations differed in 7 of 33 subjects (7/33 with a variation of at least three levels); thus, the s.d. and SRD were higher than in chronic subjects. There are several explanations for this disparity. Acute patients can be less stable in their day-to-day performance, or they could be more difficult to evaluate, particularly with regard to the issue of safety, which clearly influences the choice of the therapist. Further, in the two cases in which the maximum WISCI II level was higher on the second day, a learning effect could not be excluded. However, it could not be excluded that the sample size and composition may affect the SRD in our series.

Limitations of the study

The interval between tests is a potential limitation in a reliability study, but it must be weighed against stability, because in the acute/subacute phase of SCI, changes in strength and function can occur in days rather than weeks.12, 13 The sample size was not large (N=33), and the proportion of patients at ASIA level D was greater than that at ASIA C; however, the only other study21 of reliability in acute SCI patients was small (N=22), and most subjects were ASIA D.

Secondly, the SRD has been suggested to provide an indication of whether a patient achieved a real improvement beyond measurement noise,24, 25 and to reflect reproducibility and responsiveness of a measure;14 therefore its use has been suggested to calculate the sample size in clinical trials and to evaluate the primary outcome measure.14 However, it should be highlighted that such instrument does not consider the subject’s perspective on what could be considered a worthwhile change, on the costs and the risks as it depends on the psychometric properties of the outcome measure under evaluation.26 As in rehabilitation, the client’s perspective is highly valued, additional studies on the clinical significance of the WISCI II that include an assessment of the subjects’ perceptions of the impact of the improvement are needed.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the WISCI II has high IRR and intrarater reliability. Further, the WISCI II has good reproducibility as assessed by the ICCs and SRDs. Thus, the WISCI II is a reliable and useful outcome measure that can be used to detect changes in walking function following acute/subacute SCI.

DATA ARCHIVING

There were no data to deposit.

References

Ditunno PL, Patrick M, Stineman M, Morganti B, Townson AF, Ditunno JF . Cross-cultural differences in preference for recovery of mobility among spinal cord injury rehabilitation professionals. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 567–575.

Ditunno JF Jr, Ditunno PL, Graziani V, Scivoletto G, Bernardi M, Castellano V et al. Walking index for spinal cord injury (WISCI): an international multicenter validity and reliability study. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 234–243.

Dittuno PL, Ditunno JF Jr . Walking index for spinal cord injury (WISCI II): scale revision. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 654–656.

Morganti B, Scivoletto G, Ditunno P, Ditunno JF, Molinari M . Walking index for spinal cord injury (WISCI): criterion validation. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 27–33.

Ditunno JF Jr, Barbeau H, Dobkin BH, Elashoff R, Harkema S, Marino RJ et al. Validity of the walking scale for spinal cord injury and other domains of function in a multicenter clinical trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2007; 21: 539–550.

Jackson AB, Carnel CT, Ditunno JF, Read MS, Boninger ML, Schmeler MR et al. Outcome measures for gait and ambulation in the spinal cord injury population. J Spinal Cord Med 2008; 31: 487–499.

Ditunno JF Jr, Ditunno PL, Scivoletto G, Patrick M, Dijkers M, Barbeau H et al. The walking index for spinal cord injury (WISCI/WISCI II): nature, metric properties, use and misuse. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 346–355.

Marino RJ, Scivoletto G, Patrick M, Tamburella F, Read MS, Burns AS et al. Walking index for spinal cord injury version 2 (WISCI-II) with repeatability of the 10-m walk time: Inter- and intrarater reliabilities. Am J Phys MedRehabil 2010; 89: 7–15.

Burns AS, Delparte JJ, Patrick M, Marino RJ, Ditunno JF . The reproducibility and convergent validity of the walking index for spinal cord injury (WISCI) in chronic spinal cord injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2011; 25: 149–157.

Scivoletto G, Tamburella F, Foti C, Marco Molinari M, John F, Ditunno JF . Walking index for spinal cord injury (WISCI) reliability in patients with acute spinal cord injury (SCI). Abstract Book of the International Congress on Spinal Cord Medicine and Rehabilitation., Washington, DC, USA, 6–8 June, 2011 p 61.

American Spinal Injury Association. International Standards for Neurological Classifications of Spinal Cord Injury (revised). American Spinal Injury Association: Chicago, IL, USA. 2000.

Kimberlin CL, Winterstein AG . Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2008; 65: 2276–2284.

Fawcett JW, Curt A, Steeves JD, Coleman WP, Tuszynski MH, Lammertse D et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 190–205.

Beckerman H, Roebroeck ME, Lankhorst GJ, Becher JG, Bezemer PD, Verbeek AL . Smallest real difference, a link between reproducibility and responsiveness. Qual Life Res 2001; 10: 571–578.

Kottner J, Audige L, Brorson S, Donner A, Gajewski BJ, Hróbjartsson A et al. Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) were proposed. Int J Nurs Stud 2011; 48: 661–671.

Domholdt E . Rehabilitation Research: Principles and Applications 3rd edn. Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA. 2005.

Steeves JD, Lammertse D, Curt A, Fawcett JW, Tuszynski MH, Ditunno JF et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury (SCI) as developed by the ICCP panel: clinical trial outcome measures. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 206–221.

Curt A, Van Hedel HJ, Klaus D, Dietz V . Recovery from a spinal cord injury: significance of compensation, neural plasticity, and repair. J Neurotrauma 2008; 25: 677–685.

van Hedel HJ, Wirz M, Dietz V . Standardized assessment of walking capacity after spinal cord injury: the European network approach. Neurol Res 2008; 30: 61–73.

Kim MO, Burns AS, Ditunno JF Jr, Marino RJ . The assessment of walking capacity using the walking index for spinal cord injury: self-selected versus maximal levels. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: 762–767.

Lam T, Noonan VK, Eng JJ . A systematic review of functional ambulation outcome measures in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 246–254.

Dawson J, Shamley D, Jamous MA . A structured review of outcome measures used for the assessment of rehabilitation interventions for spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 768–780.

van Hedel HJ, Wirz M, Curt A . Improving walking assessment in subjects with an incomplete spinal cord injury: responsiveness. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 352–356.

Chen HM, Chen CC, Hsueh IP, Huang SL, Hsieh CL . Test-retest reproducibility and smallest real difference of 5 hand function tests in patients with stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009; 23: 435–440.

Vaz S, Falkmer T, Passmore AE, Parsons R, Andreou P . The case for using the repeatability coefficient when calculating test-retest reliability. PLoS One 2013; 8: e73990.

Barrett B, Brown D, Mundt M, Brown R . Sufficiently important difference: expanding the framework of clinical significance. Med Decis Making 2005; 25: 250–261.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank MA and RC, the physical therapists who performed the assessments of the WISCI. The suggestions and corrections of Professor Ralph Marino (Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA) are gratefully acknowledged. This work has been funded by a grant of the International Foundation for Research in Paraplegie (IRP, P133) to GS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scivoletto, G., Tamburella, F., Laurenza, L. et al. Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury version II in acute spinal cord injury: reliability and reproducibility. Spinal Cord 52, 65–69 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.127

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.127

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A therapist-administered self-report version of the Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury II (WISCI): a psychometric study

Spinal Cord (2024)

-

Effect of pelvic laparoscopic implantation of neuroprosthesis in spinal cord injured subjects: a 1-year prospective randomized controlled study

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Long-term clinical observation of patients with acute and chronic complete spinal cord injury after transplantation of NeuroRegen scaffold

Science China Life Sciences (2022)

-

Measures and Outcome Instruments for Pediatric Spinal Cord Injury

Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports (2016)