Abstract

Introduction:

Pressure ulcers (PUs) are a common complication following spinal cord injury (SCI). Prevalence for persons in the chronic SCI stage varies between 15 and 30%. The risk assessment scales used nowadays were designed on pathophysiological concepts and are not SCI-specific. Recently, an epidemiological approach to PU risk factors has been proposed for designing an SCI-specific assessment tool. The first results seem quite disappointing, probably because of the level of evidence of the risk factors used.

Objective:

To determine PU risk factors correlated to the chronic stage of SCI.

Materials and methods:

Systematic review of the literature.

Results:

There are several PU risk factors for chronic SCI stage: socio-demographics, neurological, medical or behavioral. The level of evidence varies: it is quite high for the socio-demographics and neurological factors and low for behavioral factors.

Discussion and conclusion:

Behavioral risk factors (relieving the pressure, careful skin monitoring, smoking) are probably the ones for which a preventive strategy can be established. It is important to develop specific assessment tools for these behavioral risk factors to determine their relevance and evaluate the effect of therapeutic educational programs on persons with SCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Pressure ulcers (PUs) are now the most common complication for persons with spinal cord injury (SCI),1, 2 despite the large number of recommendations available for information and prevention and the technological progress made for preventing and treating PU. PU have become the second cause of rehospitalization after an SCI,3 with estimated annual costs amounting to $1.4 billion in the United States.4

During the acute stage, meaning before the patient's admission to a Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R) Center, 21–37% of SCI patients go on to develop a PU.5, 6 The PM&R stay does not seem to be a risk period as only 2% of SCI patients leaving a rehabilitation center for a first-time PM&R care are affected by a PU.7 PU prevalence in chronic SCI stage varies from 15 to 30%. The risk factors during these different stages are probably not the same.8

The goal of this systematic literature review is to evaluate today's knowledge on PU risk factors in SCI patients at each stage of their specific care.

The first part of this work focused on the acute and PM&R stages of a SCI patient's care and were reported earlier.9 The risk factors for acute SCI patients are essentially linked to the care management and duration of hospitalization stays. Clinical factors do not seem to have an effect. The literature is too scarce to define precisely the PU risk factors in PM&R units or centers.

In this second part we will focus on the PU risk factors for persons with chronic SCI.

Results

Results from the bibliographical search

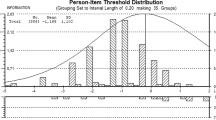

The databases search found 820 references. The first analysis from the titles and abstracts kept 40 articles. The references analysis allowed adding of two additional articles. The second analysis based on the full text excluded 20 articles.

Among the 22 studies selected, six studies focused on acute SCI patients (pre-hospital stay or in neurosurgery care). Two studies were conducted during the PM&R stage and 14 in chronic SCI patients.

PU-related risk factors in chronic SCI patients

The literature analysis reported 14 articles focusing on chronic SCI patients (Table 1).

Among these articles we find four cohort studies11, 12, 13, 14 including one historical cohort,14 one case–control study15 and nine cross-sectional studies.4, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 The study by Krause et al.19 seemed at first to use a case--control design but is in fact a cross-sectional study. The cohort studies by Chen et al.11 and Mac Kinley et al.13 focus on the same cohort from National Spinal Cord Injury Database but with a few years time gap. It seems highly likely that the data are similar in both studies.

The mean score for methodological quality is 64.7% (E=42.8–82.1). The number of patients included varied from 118 to 677613 with a total number of 15,827. The studies that included the largest number of patients11, 13 are also those with the best methodological level.

Pressure ulcers (PUs) were clinically and directly evaluated in seven studies and by questionnaire in seven other studies.

The literature search found 40 risk factors that were studied and could be classified as such:

Socio-demographic factors (Table 2)

Sex was accounted for in eight studies. No cross-sectional study found a link with the onset of a PU.4, 17, 19, 20, 21 Being male was found to be a risk factor in two high-power cohort studies, thus validating this risk factor with a strong level of evidence.11, 13 The odds ratio (OR) was evaluated at 1.3 (95% CI=1.1–1.7).

Age is not a PU risk factor for the chronic SCI patient. This was validated by cross-sectional4, 17, 20, 21 or cohort studies.11, 12, 13, 14 There was strong level of evidence.

Ethnicity is a controversial risk factor, but it was only reported in one cohort study conducted in the United States.11 There might be some confusing factors, mainly socio-economic, which are specific to African-American populations in the United States. Thus it seems impossible to extrapolate this factor for the rest of the world.

The results regarding marital status are conflicting in several cross-sectional studies.4, 17, 18 A cohort study with a good methodological level11 considers that being married is a protective factor (OR=0.7; 95% CI=0.6–0.8). The level of evidence is moderate.

A low educational achievement level is linked to PU prevalence in cross-sectional studies,18, 21 and is a risk factor in a cohort study11 (OR=1.3; 95% CI=1.1–1.5). This factor has not been identified in another cohort study with a lower methodological quality.12 The level of evidence is moderate.

Unemployment is linked to PU prevalence in several cross-sectional studies,18, 19, 20, 21 except the one by Raghavan et al.17 The cohort study by Chen et al.11 indirectly confirms this relationship by showing that being employed or a student is a protective factor with an odds ratio evaluated at 0.7 (95% CI=0.6–0.9). Two other cohort studies with a lower methodological quality do not report this correlation. The level of evidence is moderate.

Neurological factors (Table 2)

Young age at the time of the injury is a PU-related risk factor in a cross-sectional study12, 21 and a cohort study with higher methodological quality.12 The level of evidence is moderate.

Time Since Injury is a PU-related factor in several cross-sectional studies12, 21, 22 and is validated by three cohort studies.12, 13, 24 Only the cross-sectional studies by Fuhrer et al.4 and Krause20 as well as the cohort study by Salzberg14 do not confirm this causal relationship. We can consider that the PU risk increases with time since injury with a strong level of evidence.

The SCI trauma etiology is considered as a risk factor by a first cohort study.13 This notion is undermined by a second cohort study,11 which does not find this relationship, taking into account the multivariate analysis of the demographic factors described above. We cannot consider SCI etiology as a risk factor, with a moderate level of evidence.

Only one cross-sectional study associates the onset of PU with a cervical injury level.20 Other cross-sectional4, 19, 22 or cohort studies11, 13, 14 do not report any link between injury level and the onset of a PU. The level of evidence is strong.

Transversal extension of the SCI, assessed by the ASIA or Frankel score, is a PU risk factor for chronic SCI patients found in two cohort studies,11, 13 one historical cohort14 and two cross-sectional studies.20, 21 The level of evidence is strong. Odds ratios, according to Chen,11 are 8 (95% CI=5.6–11.3) for an ASIA A score of 6 (95% CI=4.1–8.8) for an ASIA B score and 3 (95% CI=2.1–4.4) for an ASIA C score. According to the cross-sectional study by Sumiya et al.,16 there is no correlation between PU and sensibility disorders at the seating level.

Vertical extension of the SCI, assessed by the ASIA Motor Index, is a suggested risk factor in one cross-sectional study4 and is validated by a cohort study.12 The level of evidence is moderate.

Medical and biological factors (Table 3)

Several medical pathologies associated with SCI have been studied. The results with regard to the cardiovascular pathologies are discordant and were evaluated in studies with a methodological level that was too low14, 15 to come to any conclusions. These studies also assessed the effect of diabetes mellitus, without finding any correlation. The level of evidence is insufficient. Other intercurrent pathologies were identified as risk factors in two cohort studies with a very good methodological level.11, 13 The level of evidence is strong for deep venous thrombosis and infectious pneumopathy, and moderate for fractures of the lower limbs and autonomic dysreflexia.

Only one retrospective cohort study14 evaluated the effect of low albumin levels on the onset of PU and found a significant relationship. The level of evidence is insufficient.

Impairment and disability

Impairment, assessed by the FIM scale, is a risk factor suggested by a cross-sectional study4 and was validated by a cohort study.12 The level of evidence is moderate.

The mobility level (walking, in a wheelchair or in bed) was evaluated in a case study and a historical cohort study. A low mobility level is a PU risk factor with a moderate level of evidence.

Handicap is a risk factor found in one cohort study.12 The level of evidence is insufficient.

Bladder or bowel incontinence is also a risk factor suggested in epidemiological studies. Sumiya et al. found a causal relationship between bladder incontinence and PU existence in a cross-sectional study.16 Raghavan et al.17 found no correlation between PU and bladder or bowel incontinence in another cross-sectional study. However, Salzberg et al.14 found a statistical link in a historical cohort study with a low methodological level. Bladder incontinence is a risk factor but there is an insufficient level of evidence.

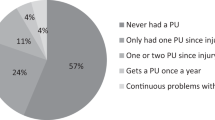

Factors linked to a medical history of PUs

History of PU surgical treatment was reported in two studies and is being identified as a risk factor for recurrent PU.12, 15

PU medical history11, 12, 21 is a risk factor for recurrent PU found in a cross-sectional study21 and two cohort studies11, 12 (OR: 1.4; 95% CI=1.2–1.6).

Skin-specific protective behaviors (Table 4)

These are the specific prevention techniques taught to SCI patients during their PM&R stay.

A daily skin check-up is found to be a protective behavior in one cross-sectional study,17 but not in two other cross-sectional studies.17, 19 A cohort study reports a correlation between daily skin monitoring at the time of inclusion and the lack of PU onset up to the third year of follow-up.12 We can consider skin monitoring as a protective factor with a moderate level of evidence.

The other practices taught to patients such as weight redistribution,17, 18, 19 or regular repositioning in bed,18, 19 are not associated with the lack of a PU. The studies reporting these elements are cross-sectional. For these cross-sectional studies we find a confusion bias for evaluating these factors: some patients who developed a PU at the time of the survey had probably increased their prevention level because of this affection. There is no longitudinal study available for these factors. We cannot determine the importance of these protective factors.

General protective health behaviors

Some general factors, such as daily exercising, healthy diet or a healthy lifestyle were assessed in cross-sectional studies,18, 19 with conflicting results. Thus, they are potentially protective factors with an insufficient level of evidence.

Toxic substances and psychological factors

Cigarette smoking is a risk factor identified in three cross-sectional studies17, 18, 19 and confirmed by a historical cohort study.14 The statistical link tends to be quite significant (P=0.057) in a case--control study.15 The level of evidence is moderate.

Alcohol abuse is not a PU-related risk factor in a cross-sectional study18 and a retrospective cohort study. The level of evidence is moderate.

A cross-sectional study19 reports a link between taking hypnotic drugs and the formation of a PU. It is a potential risk factor with an insufficient level of evidence.

If suicidal behaviors were not related to PU prevalence in a first cross-sectional study,18 depression and personality disorders such as anxiety were linked to PU in a second cross-sectional study.19 They are potential risk factor with an insufficient level of evidence.

Care-related risk factors

SCI patients being hospitalized for an affection other than PU is also found to be a risk factor, with a moderate level of evidence (OR=1.8; 95% CI=1.6–2.2).11

Discussion

The objective of this second part of our systematic literature review was to determine the PU risk factors in chronic SCI patients.

Contrary to the risk factors found in the acute stage of SCI patients’ care,9 the risk factors for chronic SCI patients are quite numerous and depend for the major part on the socio-demographic, medical, neurological, cutaneous or behavioral characteristics of the patients.

The results from the epidemiological studies are similar for most of the risk factors found in our review. It is, however, necessary to modulate some of them.

The African American origin is reported as a PU risk factor in a US cohort study.11 The African American SCI subpopulation is very different from the rest of the SCI population at a social level but also at a medical level: violent etiology is more frequent (gunshot wounds), unemployment, lower level of education, difficulty in access to proper healthcare ….26 This risk factor is most probably correlated to specific US characteristics and should only be carefully extrapolated to other countries.

The results regarding history of former PU surgery are apparently conflicting between two studies. A more precise analysis of the studied criteria showed that these results might not be opposed. Niazi et al. reported in a case--control study15 that having a history of PU surgery was not related to PU recurrence at the same location in the long term, suggesting that PU surgery does not weaken the skin tissue in the long-term. Garber et al., in a cohort study,12 highlighted that a history of PU surgery was correlated to PU recurrence without furnishing any details of the precise location of this recurrence (on the surgical site or not). This matches the clinical picture of patients with recurrent PUs.

Medical history of PUs is also a PU risk factor. Cohort studies reporting this correlation do not precisely indicate if it is a recurrent PU or if the PU originates at another location. In the first case, the time delay up to PU recurrence is interesting to analyze as the remodeling of the scar tissue, at an anatomopathological level, takes about 18 months and this delay is theoretically a period of cutaneous weakness.27, 28, 29 In the second case, this relationship tends to highlight the predisposition of some patients to develop recurrent PUs. The link between PU recurrence and PU surgery must be interpreted with caution. An existing PU—which is a risk factor for recurrence—can already be a potentially confusing factor. Surgical indication and surgical techniques and post-surgical care must also be carefully evaluated before validating them as risk factors.

If, on an anatomopathological risk factor scale, urine and feces toxicity on the skin is quite admitted,30 the level of evidence for the effect of bladder/bowel incontinence at the onset of PU in SCI patients is low.14, 16, 17 In comparison, cohort studies conducted in elderly individuals at home show that bladder/bowel incontinence is a risk factor for PU.31, 32, 33 A recent case--control study34 undermines the effect of urinary incontinence in elderly individuals, by including in the multivariate analysis the individual's degree of independence in daily life activities. Urinary incontinence would only be a confusing factor for other variables related to the loss of independence.

Cigarette smoking is a PU risk factor with a moderate level of evidence. The pathophysiological context of this factor is the effect that smoking has on cutaneous blood flow.35, 36, 37, 38 Viehbeck et al.39 have evaluated the effect of an educational program delivered to SCI patients on the effects of smoking on PU development and scarring. This educational message was delivered through videotape and was memorized in the short term. The effect of this type of prevention on the development of PU onset has not been assessed. “Protective” factors (weight redistributing, self-repositioning, daily skin monitoring, etc.) were assessed in cross-sectional studies thus leading to a bias: it is difficult to know whether this behavior occurs before or after the development of a PU. The level of evidence of these educational practices, taught daily to our patients, is very insufficient.

We were also quite surprised by the low level of evidence and the very few number of studies focusing on the psychological risk factors as these recurrence factors are often encountered in everyday clinical practice.

The analysis of the risk factors for chronic SCI highlights two types of risk factors: on the one hand, the risk factors that are easy to quantify with a level of evidence that is sometimes highly satisfying, such as socio-demographic factors or neurological factors. These factors are hardly affected by prevention. In contrast, there is another category of risk factors with a very low level of evidence and it is hard to quantify it as a behavioral factors category. Behavioral factors can, however, benefit for a primary or secondary prevention strategy: in fact, educational programs for the prevention of PUs development are part of the missions of physical medicine and rehabilitation.40, 41 Furthermore, educational programs or training on PU prevention have a positive effect on the knowledge of the healthcare professionals and thus on PU incidence.42, 43, 44, 45 SCI patients must leave their PM&R center with a good understanding of this pathology and how to prevent the development of PUs as they will be in charge of this prevention at home.

Study limits

Besides the limits listed in the first part of this study,9 the inclusion of cross-sectional studies in the systematic review was particularly problematic in the second part of our literature review; this study type does not always show a causality relationship, mandatory for validating a risk factor. In fact, the temporal sequence (does the incriminated factor take place before or after the development of the disease?—is not easy to establish. We took this bias into account by grading the causality relationship according to the type of study and its methodological quality.

Perspectives

The evaluation of implementing an educational workshop on PU prevention for SCI patients must be based on two aspects: first the beliefs and knowledge of patients both in the short and middle term; and second, the effect in terms of PU incidence in primary or secondary prevention.

Garber et al.46 conducted a pilot study evaluating the effect of a standardized educational program in a low-power, randomized controlled study on a population of SCI patients hospitalized for PU surgery (N=41). The effect of the patients’ knowledge, assessed by a non-validated questionnaire and the PU recurrence rate are significant for up to 24 months of follow-up. The preliminary results had motivated this team to continue and expand the clinical study with a provisional sample group of 278 patients over a 4-year period47 to increase the power of the study. The recruiting difficulties and the patients that were unavailable for follow-up did not allow finalization this study. In a second publication on this study, the authors focused on the effect of educational programs on PU recurrence with a positive effect of an individualized educational program with a structured follow-up on the time delay before PU recurrence.48

Finally, it is necessary to discuss the efficacy of an educational strategy that would require the creation and validation of an evaluation tool. A scale allowing evaluation of the knowledge of SCI patients on skin risk factors and PU prevention was recently published in the English language.49, 50, 51 This tool could evaluate, in an objective manner, the effect of an educational workshop and also increase the level of evidence of behavioral factors. A validation project in the French language is underway.

Conclusion

The aim of this literature review was to determinate the risk factors for PU development at each stage of SCI patients’ care. During acute SCI, the risk factors are essentially related to care modalities, whereas for chronic SCI stage, there are more risk factors: socio-demographic, clinical and behavioral. The level of evidence of the various factors varies, which could be the focus of additional and complementary studies. The results of this review justify rethinking the organization of care and the management of PU prevention during the various stages of SCI patients’ care.

References

Whiteneck GG, Charlifue SW, Frankel HL, Fraser MH, Gardner BP, Gerhart KA et al. Mortality, morbidity, and psychosocial outcomes of persons spinal cord injured more than 20 years ago. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 617–630.

Johnson RL, Gerhart KA, McCray J, Menconi JC, Whiteneck GG . Secondary conditions following spinal cord injury in a population-based sample. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 45–50.

Cardenas DD, Hoffman JM, Kirshblum S, McKinley W . Etiology and incidence of rehospitalization after traumatic spinal cord injury: a multicenter analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1757–1763.

Fuhrer MJ, Garber SL, Rintala DH, Clearman R, Hart KA . Pressure ulcers in community-resident persons with spinal cord injury: prevalence and risk factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993; 74: 1172–1177.

Sheerin F, Gillick A, Doyle B . Pressure ulcers and spinal-cord injury: incidence among admissions to the Irish national specialist unit. J Wound Care 2005; 14: 112–115.

Curry K, Casady L . The relationship between extended periods of immobility and decubitus ulcer formation in the acutely spinal cord-injured individual. J Neurosci Nurs 1992; 24: 185–189.

Ash D . An exploration of the occurrence of pressure ulcers in a British spinal injuries unit. J Clin Nurs 2002; 11: 470–478.

Pires M, Adkins R . pressures ulcers and spinal cord injury: scope of the problem. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation 1996; 2: 1–8.

Gelis A, Dupeyron A, Legros P, Benaim C, Pelissier J, Fattal C . Pressure ulcer risk factors in persons with SCI: part I: acute and rehabilitation stages. Spinal Cord 2008.

Green S, Higgins J . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.5. In: http://www.cochrane.org/resources/handbook/ May 2005.

Chen Y, Devivo MJ, Jackson AB . Pressure ulcer prevalence in people with spinal cord injury: age-period-duration effects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 86: 1208–1213.

Garber SL, Rintala DH, Hart KA, Fuhrer MJ . Pressure ulcer risk in spinal cord injury: predictors of ulcer status over 3 years. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81: 465–471.

McKinley WO, Jackson AB, Cardenas DD, DeVivo MJ . Long-term medical complications after traumatic spinal cord injury: a regional model systems analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1402–1410.

Salzberg CA, Byrne DW, Cayten CG, van Niewerburgh P, Murphy JG, Viehbeck M . A new pressure ulcer risk assessment scale for individuals with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 75: 96–104.

Niazi ZB, Salzberg CA, Byrne DW, Viehbeck M . Recurrence of initial pressure ulcer in persons with spinal cord injuries. Adv Wound Care 1997; 10: 38–42.

Sumiya T, Kawamura K, Tokuhiro A, Takechi H, Ogata H . A survey of wheelchair use by paraplegic individuals in Japan. Part 2: Prevalence of pressure sores. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 595–598.

Raghavan P, Raza WA, Ahmed YS, Chamberlain MA . Prevalence of pressure sores in a community sample of spinal injury patients. Clin Rehabil 2003; 17: 879–884.

Krause JS, Vines CL, Farley TL, Sniezek J, Coker J . An exploratory study of pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury: relationship to protective behaviors and risk factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82: 107–113.

Krause JS, Broderick L . Patterns of recurrent pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury: identification of risk and protective factors 5 or more years after onset. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1257–1264.

Krause JS . Skin sores after spinal cord injury: relationship to life adjustment. Spinal Cord 1998; 36 (1): 51–56.

Klotz R, Joseph PA, Ravaud JF, Wiart L, Barat M . The Tetrafigap Survey on the long-term outcome of tetraplegic spinal cord injured persons: Part III. Medical complications and associated factors. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 457–467.

Anson CA, Shepherd C . Incidence of secondary complications in spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res 1996; 19: 55–66.

Anderson TP, Andberg MM . Psychosocial factors associated with pressure sores. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1979; 60: 341–346.

Chen D, Apple Jr DF, Hudson LM, Bode R . Medical complications during acute rehabilitation following spinal cord injury—current experience of the Model Systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1397–1401.

Byrne DW, Salzberg CA . Major risk factors for pressure ulcers in the spinal cord disabled: a literature review. Spinal Cord 1996; 34: 255–263.

Meade MA, Lewis A, Jackson MN, Hess DW . Race, employment, and spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1782–1792.

Yamaguchi Y, Yoshikawa K . Cutaneous wound healing: an update. J Dermatol 2001; 28: 521–534.

Kanzler MH, Gorsulowsky DC, Swanson NA . Basic mechanisms in the healing cutaneous wound. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1986; 12: 1156–1164.

Diegelmann RF, Evans MC . Wound healing: an overview of acute, fibrotic and delayed healing. Front Biosci 2004; 9: 283–289.

Ersser SJ, Getliffe K, Voegeli D, Regan S . A critical review of the inter-relationship between skin vulnerability and urinary incontinence and related nursing intervention. Int J Nurs Stud 2005; 42: 823–835.

Brandeis GH, Ooi WL, Hossain M, Morris JN, Lipsitz LA . A longitudinal study of risk factors associated with the formation of pressure ulcers in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994; 42: 388–393.

Bergquist S, Frantz R . Pressure ulcers in community-based older adults receiving home health care. Prevalence, incidence, and associated risk factors. Adv Wound Care 1999; 12: 339–351.

Bergquist S . Pressure ulcer prediction in older adults receiving home health care: implications for use with the OASIS. Adv Skin Wound Care 2003; 16: 132–139.

Krause T, Anders J, von Renteln-Kruse W . [Urinary incontinence as a risk factor for pressure sores does not withstand a critical examination]. Pflege 2005; 18: 299–303.

Noble M, Voegeli D, Clough GF . A comparison of cutaneous vascular responses to transient pressure loading in smokers and nonsmokers. J Rehabil Res Dev 2003; 40: 283–288.

Ijzerman RG, Serne EH, van Weissenbruch MM, de Jongh RT, Stehouwer CD . Cigarette smoking is associated with an acute impairment of microvascular function in humans. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003; 104: 247–252.

Dalla Vecchia L, Palombo C, Ciardetti M, Porta A, Milani O, Kozakova M et al. Contrasting effects of acute and chronic cigarette smoking on skin microcirculation in young healthy subjects. J Hypertens 2004; 22: 129–135.

Black CE, Huang N, Neligan PC, Levine RH, Lipa JE, Lintlop S et al. Effect of nicotine on vasoconstrictor and vasodilator responses in human skin vasculature. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2001; 281: R1097–R1104.

Viehbeck M, McGlynn J, Harris S . Pressure ulcers and wound healing: educating the spinal cord injured individual on the effects of cigarette smoking. SCI Nurs 1995; 12: 73–76.

Brillhart B, Stewart A . Education as the key to rehabilitation. Nurs Clin North Am 1989; 24: 675–680.

Basta SM . Pressure sore prevention education with the spinal cord injured. Rehabil Nurs 1991; 16: 6–8.

Abel RL, Warren K, Bean G, Gabbard B, Lyder CH, Bing M et al. Quality improvement in nursing homes in Texas: results from a pressure ulcer prevention project. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2005; 6: 181–188.

Sinclair L, Berwiczonek H, Thurston N, Butler S, Bulloch G, Ellery C et al. Evaluation of an evidence-based education program for pressure ulcer prevention. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2004; 31: 43–50.

Tetterton M, Parham IA, Coogle CL, Cash K, Lawson K, Benghauser K et al. The development of an educational collaborative to address comprehensive pressure ulcer prevention and treatment. Gerontol Geriatr Educ 2004; 24: 53–65.

Wilson G, Logan H . The role of education, technique and equipment in pressure area care. Br J Nurs 2005; 14: 990–994.

Garber SL, Rintala DH, Holmes SA, Rodriguez GP, Friedman J . A structured educational model to improve pressure ulcer prevention knowledge in veterans with spinal cord dysfunction. J Rehabil Res Dev 2002; 39: 575–588.

Guihan M, Garber SL, Bombardier CH, Durazo-Arizu R, Goldstein B, Holmes SA . Lessons learned while conducting research on prevention of pressure ulcers in veterans with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: 858–861.

Rintala DH, Garber SL, Friedman JD, Holmes SA . Preventing recurrent pressure ulcers in veterans with spinal cord injury: impact of a structured education and follow-up intervention. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008; 89: 1429–1441.

Berry C, Kennedy P . A psychometric analysis of the Needs Assessment Checklist (NAC). Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 490–501.

Berry C, Kennedy P, Hindson LM . Internal consistency and responsiveness of the Skin Management Needs Assessment Checklist post-spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2004; 27: 63–71.

Kennedy P, Berry C, Coggrave M, Rose L, Hamilton L . The effect of a specialist seating assessment clinic on the skin management of individuals with spinal cord injury. J Tissue Viability 2003; 13: 122–125.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Fondation Paul Bennetot for their research funding as well as Christine Gilbert for her precious bibliographical research, Frank Dreyer for his help with the results and Bénédicte Clément for her translation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gélis, A., Dupeyron, A., Legros, P. et al. Pressure ulcer risk factors in persons with spinal cord injury Part 2: the chronic stage. Spinal Cord 47, 651–661 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.32

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.32

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multidisciplinary treatment protocol for ischiatic, sacral, trochanteric or other pressure injuries in people with spinal cord injury: a retrospective cohort study

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Reconstructive procedure for treatment of trochanteric pressure ulcers in spinal-cord-injured patients

European Journal of Plastic Surgery (2023)

-

Community dwelling life- and health issues among persons living with chronic spinal cord injury in North Macedonia

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Factors affecting adherence to behaviours appropriate for the prevention of pressure injuries in people with spinal cord injury from Malaysia: a qualitative study

Spinal Cord (2021)

-

Pressure ulcers after traumatic spinal injury in East Africa: risk factors, illustrative case, and low-cost protocol for prevention and treatment

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2020)