Abstract

Study design:

Case report.

Objective:

To report on an uncommon patient of cervical spinal cord sarcoidosis.

Setting:

New York, USA.

Methods:

A 47-year-old man was evaluated for heaviness of his legs, difficulty walking and numbness of arms and feet for 6 months. Contrast enhanced MRI scan showed a strongly enhancing nodular lesion, suggestive of a spinal cord tumor, which was initially considered for neurosurgical biopsy and treatment. Investigations unexpectedly revealed mediastinal lymphadenopathy and elevated angiotensin converting enzyme levels and the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was confirmed by a transbronchial lung biopsy.

Result:

Prompt treatment with steroids resulted in complete clinical and radiological resolution of the spinal cord lesion within 4 weeks. This improvement was maintained over a 18 month follow-up period.

Conclusion:

Isolated spinal cord intramedullary enhancing lesions, even when the appearance is suggestive of a tumor, should be rigorously investigated for sarcoidosis and a trial of steroid therapy considered to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic, non-caseating granulomatous disease. Central nervous system involvement occurs in 5–10% of cases. Sarcoid granulomas can affect the pituitary gland, hypothalamus, meninges, parenchyma of the brain, brainstem, spinal cord, peripheral nerves and blood vessels supplying the nervous system structures.1 Primary spinal cord involvement in sarcoidosis is very uncommon, estimated at 0.3–0.4% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis.2 We describe here a patient with intra-medullary spinal cord sarcoidosis which was initially diagnosed as a spinal cord tumor on the basis of the appearance on the contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Accurate diagnosis is important to avoid the severe neurologic sequelae associated with unnecessary surgery or delayed treatment.

Case report

A 47-year-old man was evaluated for complaints of heaviness of his legs and unsteadiness for the past six months. One month ago he developed neck pain and numbness of the medial aspect of his forearms and thorax and also the soles of his feet. He also complained of erectile dysfunction and decreased genital sensation during micturition for 1 month. Motor examination was normal. Sensory examination revealed decreased pinprick, vibration and position sense in both lower extremities up to the thighs and the medial aspect of arms. Perianal sensation was normal and rectal tone was normal. Deep tendon reflexes were normal. A positive Babinski sign was found on the right.

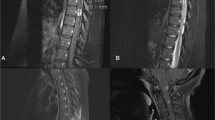

Cranial MRI scan was normal. T2-weighted images of spine MRI revealed a high signal extending from the craniocervical region down to the T1 level with expansion of the cervical spinal cord. On contrast administration a nodular, irregular enhancing lesion was noted extending from C2 to T1 level (Figures 1a and b). Serum B12 levels was 660 pg ml−1 (Normal >250 pg ml−1). NMO-IgG autoantibodies were absent in serum. The initial differential diagnosis considered was that of a spinal cord tumor such as astrocytoma, ependymoma or hemangioblastoma. Neurosurgical biopsy was planned.

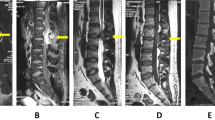

(a) Sagittal T2-weighted MRI scan of cervical spine shows high signal within the spinal cord extending from cranio-cervical junction to T1 level (arrow). (b) Sagittal T1 post contrast scan shows nodular enhancing lesion extending from C2 to T1 level (arrow). (c) Chest X-ray shows prominent hila and enlarged superior mediastinal shadow suggestive of lymphadenopathy (arrow) (d) Axial chest Computerized Tomography scan shows significant bilateral mediastinal lymphadenopathy (arrow).

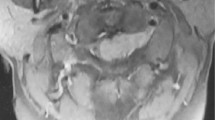

However, chest X-ray and Computerized Tomography scan of the chest demonstrated significant bilateral hilar, paratracheal and subcarinal lymphadenopathy (Figures 1c and d). Angiotensin converting enzyme level was increased to 99 (normal 8–52 U l−1). Transbronchial biopsy of the superior segment of the right upper lobe revealed a non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation consistent with sarcoidosis. The patient was treated with methylprednisolone 20 mg kg−1 daily i.v. for 5 days followed by 80 mg day−1 of Prednisone. Marked clinical improvement started in 2 weeks and resolution of all symptoms occurred by 4 weeks and the patient remained asymptomatic for 18 months on continuing maintenance Prednisone of 30 mg day−1. Repeat cervical spine MRI scans done after 1 month showed complete disappearance of the spinal cord lesions on both T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced MRI scans (Figures 2a and b). Another MRI scan done after 13 months did not reveal any recurrence of lesions.

Discussion

Spinal sarcoidosis is rare and encompasses a spectrum of intraspinal disease that includes arachnoiditis, cauda equina syndrome, extradural, intradural extramedullary and intramedullary lesions. In a review of the literature of 48 cases of spinal cord sarcoidosis, intramedullary involvement was seen in 35% of cases, extramedullary involvement in 35% of cases and both were involved in 23% of patients.3 Half of the cases with intramedullary involvement had evidence of systemic sarcoidosis. The cervical cord was involved in 70% of the cases.3 Spinal cord sarcoidosis begins with linear leptomeningeal involvement along the surface of the spinal cord, followed by parenchymal involvement secondary to spread of the inflammatory process along the Virchow–Robin perivascular spaces.4 In the long term there is abatement of the inflammatory process with residual neuronal damage and spinal cord atrophy. The primary differential diagnosis of longitudinally extensive myelopathies include spinal cord tumor, syringomyelia, neuromyelitis optica (NMO) and vitamin B12, vitamin E or copper deficiency myelopathies. Normal serum levels of serum vitamin B12 and rapid reversibility over 1 month to normal made copper, vitamin B12 or vitamin E deficiency myelopathy very unlikely. NMO is an important cause of a demyelinating spinal cord lesion extending over three vertebral segments. However, unlike our patient, NMO usually presents with relapsing remitting attacks of both optic neuritis and myelitis. Also, NMO-IgG autoantibodies to aquaporin-4 (which are seen in about 90% of NMO patients) was absent in our patient making that diagnosis unlikely.

Our patient illustrates the importance of not proceeding with neurosurgery till a careful evaluation for evidence of the systemic sarcoidosis is completed. Avoiding unnecessary surgery is especially important because patients with intramedullary sarcoid who have been inadvertently operated have done poorly, with progressive neurological deterioration, in spite of steroid therapy.5 Moreover, spinal cord biopsy may be negative in intramedullary sarcoidosis as spinal cord granulomas may be poorly formed, smaller than the systemic granulomas and have fewer giant cells, emphasizing the importance of recognizing and preoperatively making this diagnosis.

In patients with an otherwise unexplained spinal cord mass on MRI scan, a diagnosis of sarcoidosis should be considered and they should be carefully evaluated for the presence of systemic sarcoidosis. Furthermore, since some patients with spinal sarcoidosis may have no evidence of systemic sarcoidosis, a trial of intravenous steroids followed by oral steroids should be considered in such patients to avoid unnecessary and potentially debilitating surgery.

References

Hoitsma E, Faber CG, Drent M, Sharma OP . Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical dilemma. Lancet Neurol 2004; 3: 397–407.

Day AL, Sypert GW . Spinal cord sarcoidosis. Ann Neurol 1977; 1: 79–85.

Mathieson CS, Mowle D, Ironside JW, O’Riordan R . Isolated cervical intramedullary sarcoidosis-a histological surprise. Br J Neurosur 2004; 18: 632–635.

Sherman JL, Stern BJ . Sarcoidosis of the CNS: comparison of unenhanced and enhanced MR images. AJNR 1990; 11: 915–923.

Nesbit GM, Miller GM, Baker Jr HL, Ebersold MJ, Scheithauer BW . Spinal cord sarcoidosis: a new finding at MR imaging with Gd-DTPA enhancement. Radiology 1989; 173: 839–843.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bhagavati, S., Choi, J. Intramedullary cervical spinal cord sarcoidosis. Spinal Cord 47, 179–181 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.76

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.76

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Longitudinally extensive myelopathy in children

Pediatric Radiology (2015)