Abstract

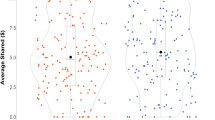

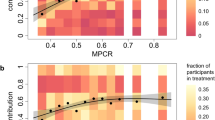

Economic status is positively associated with subjective well-being (SWB), happiness and mental health, but debate persists about the determinants of SWB in circumstances involving economic inequality. Here we implemented online experiments where subjects interact financially, gain or lose wealth, report their SWB and adjust their social ties with others across time. We assigned 1,289 subjects to be initially rich or poor in 100 networked groups and manipulated wealth visibility in the groups. In the visible wealth condition, we showed subjects the wealth of their immediate neighbours, thereby allowing social comparisons, while in the invisible wealth condition, we kept such information hidden. Results show that invisible wealth condition disproportionally improves the SWB of currently poorer subjects and thus alleviated the economic gradient in SWB. Two phenomena may explain the alleviation observed in the invisible wealth condition: initially rich subjects who become relatively poorer do not experience substantial damage to their SWB, and initially poor subjects who remain poorer may still experience an SWB gain similar to those who become richer.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$59.00 per year

only $4.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data for replicating the main results are available on A.N.’s GitHub page (https://github.com/akihironishi).

Code availability

The details of the analysis along with the R code are provided in our Supplementary Information Extended Data Methods and Results.

References

Buttrick, N. R. & Oishi, S. The psychological consequences of income inequality. Soc. Pers. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12304 (2017).

Jebb, A. T., Tay, L., Diener, E. & Oishi, S. Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 33–38 (2018).

Howell, R. T. & Howell, C. J. The relation of economic status to subjective well-being in developing countries: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 134, 536–560 (2008).

Lucas, R. E. & Schimmack, U. Income and well-being: how big is the gap between the rich and the poor? J. Res. Pers. 43, 75–78 (2009).

Diener, E. & Biswas-Diener, R. Will money increase subjective well-being? Soc. Indic. Res. 57, 119–169 (2002).

Kahneman, D. & Deaton, A. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 16489–16493 (2010).

Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 253–260 (2018).

Kelley, J. & Evans, M. D. R. Societal inequality and individual subjective well-being: results from 68 societies and over 200,000 individuals, 1981–2008. Soc. Sci. Res. 62, 1–23 (2017).

Easterlin, R. A., Mcvey, L. A., Switek, M., Sawangfa, O. & Zweig, J. S. The happiness-income paradox revisited. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 22463–22468 (2010).

Killingsworth, M. A., Kahneman, D. & Mellers, B. Income and emotional well-being: a conflict resolved. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2208661120 (2023).

Kawachi, I., Adler, N. E. & Dow, W. H. Money, schooling, and health: mechanisms and causal evidence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1186, 56–68 (2010).

Lund, C. et al. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 71, 517–528 (2010).

Kondo, N., Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S. V., Takeda, Y. & Yamagata, Z. Do social comparisons explain the association between income inequality and health?: relative deprivation and perceived health among male and female Japanese individuals. Soc. Sci. Med. 67, 982–987 (2008).

Willis, G. B., García-Sánchez, E., Sánchez-Rodríguez, Á., García-Castro, J. D. & Rodríguez-Bailón, R. The psychosocial effects of economic inequality depend on its perception. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1, 301–309 (2022).

Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 7, 117–140 (1954).

Taylor, S. E. & Lobel, M. Social comparison activity under threat: downward evaluation and upward contacts. Psychol. Rev. 96, 569–575 (1989).

Solnick, S. J. & Hemenway, D. Is more always better?: a survey on positional concerns. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 37, 373–383 (1998).

Card, D., Mas, A., Moretti, E. & Saez, E. Inequality at work: the effect of peer salaries on job satisfaction. Am. Econ. Rev. 102, 2981–3003 (2012).

Liu, K. & Wang, X. H. Relative income and income satisfaction: an experimental study. Soc. Indic. Res. 132, 395–409 (2017).

Nishi, A., Shirado, H., Rand, D. G. & Christakis, N. A. Inequality and visibility of wealth in experimental social networks. Nature 526, 426–429 (2015).

Brent, D. A., Gangadharan, L., Mihut, A. & Villeval, M. C. Taxation, redistribution, and observability in social dilemmas. J. Public Econ. Theory 21, 826–846 (2019).

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P. & Shields, M. A. Relative income, happiness, and utility: an explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. J. Econ. Lit. 46, 95–144 (2008).

Vendrik, M. C. M. & Woltjer, G. B. Happiness and loss aversion: is utility concave or convex in relative income? J. Public Econ. 91, 1423–1448 (2007).

Layard, R., Mayraz, G. & Nickell, S. J. in International Differences in Well-Being (eds Diener, E., Helliwell, J. F. & Kahneman, D.) 139–165 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010).

Clark, A. E., Fleche, S., Layard, R., Powdthavee, N. & Ward, G. In World Happiness Report 2017 (eds Helliwell, J., Layard, R. & Sachs, S.) 122–143 (Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2017).

Bertram-Hümmer, V. & Baliki, G. The role of visible wealth for deprivation. Soc. Indic. Res. 124, 765–783 (2015).

Dynan, K. E. & Ravina, E. Increasing income inequality, external habits, and self-reported happiness. Am. Econ. Rev. 97, 226–231 (2007).

Ball, R. & Chernova, K. Absolute income, relative income, and happiness. Soc. Indic. Res. 88, 497–529 (2008).

Knight, J., Song, L. & Gunatilaka, R. Subjective Well-Being And Its Determinants In Rural China. China Econ. Rev. 20, 635–649 (2009).

Fliessbach, K. et al. Social comparison affects reward-related brain activity in the human ventral striatum. Science 318, 1305–1308 (2007).

Colella, A., Paetzold, R. L., Zardkoohi, A. & Wesson, M. J. Exposing pay secrecy. Acad. Manage. Rev. 32, 55–71 (2007).

Clark, A. E. & Oswald, A. J. Satisfaction and comparison income. J. Public Econ. 61, 359–381 (1996).

Han, S. A mandatory uniform policy in urban schools: findings from the school survey on crime and safety: 2003–04. Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadership 5, 1–13 (2010).

Ball, S., Bowe, R. & Gewirtz, S. School Choice, Social Class and Distinction: The Realization of Social Advantage in Education. J. Educ. Policy. 11, 89–112 (1996).

Dolan, K. A. & Peterson-Withorn, C. Forbes worlds’ billionaires list: the richest in 2022. Forbes https://www.forbes.com/billionaires/ (2022).

University of California Office of the President. Compensation at the University of California https://ucannualwage.ucop.edu/wage/ (2022).

Lukianoff, G. & Haidt, J. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure (Penguin Books, 2019).

Royal Society for Public Health. #StatusOfMind: Social Media and Yound People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing (2017).

Braghieri, L., Levy, R. & Makarin, A. Social media and mental health. Am. Econ. Rev. 112, 3660–3693 (2022).

Alesina, A. & La Ferrara, E. Who trusts others? J. Public Econ. 85, 207–234 (2002).

Anderson, L. R., Mellor, J. M. & Milyo, J. Induced heterogeneity in trust experiments. Exp. Econ. 9, 223–235 (2006).

Tavoni, A., Dannenberg, A., Kallis, G. & Loschel, A. Inequality, communication, and the avoidance of disastrous climate change in a public goods game. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 11825–11829 (2011).

Côté, S., House, J. & Willer, R. High economic inequality leads higher income individuals to be less generous. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15838–15843 (2015).

Camerer, C. F. et al. Evaluating the replicability of social science experiments in Nature and Science between 2010 and 2015. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 637–644 (2018).

Bond, M. H., Kwan, V. S. Y. & Li, C. Decomposing a sense of superiority: the differential social impact of self-regard and regard for others. J. Res. Pers. 34, 537–553 (2000).

Berkman, L. F. Social epidemiology: social determinants of health in the United States: are we losing ground? Annu. Rev. Public Health 30, 27–41 (2009).

Berkman, L. F. et al. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) randomized trial. JAMA 289, 3106–3116 (2003).

Ludwig, J. et al. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science 337, 1505–1510 (2012).

Allen, J., Balfour, R., Bell, R. & Marmot, M. Social determinants of mental health. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 26, 392–407 (2014).

Alegria, M., NeMoyer, A., Bague, I. F., Wang, Y. & Alvarez, K. Social determinants of mental health: where we are and where we need to go. Curr. Psychiatr. Rep. 20, 95 (2018).

Galea, S. Macrosocial Determinants of Population Health (Springer, 2007).

Branas-Garza, P., Molis, E. & Neyse, L. Exposure to inequality may cause under-provision of public goods: experimental evidence. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2021.101679 (2021).

Cherry, T. L., Kroll, S. & Shogren, J. F. The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on public good contributions: evidence from the lab. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 57, 357–365 (2005).

Kroll, S., Cherry, T. L. & Shogren, J. F. The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on contributions in best-shot public good games. Exp. Econ. 10, 411–428 (2007).

Reuben, E. & Riedl, A. Enforcement of contribution norms in public good games with heterogeneous populations. Game Econ. Behav. 77, 122–137 (2013).

Noussair, C. N. & Tan, F. F. Voting on punishment systems within a heterogeneous group. J. Public Econ. Theory 13, 661–693 (2011).

Martinangeli, A. F. M. Do what (you think) the rich will do: inequality and belief heterogeneity in public good provision. J. Econ. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2021.102364 (2021).

Allison, P. D. Measures of inequality. Am. Sociol. Rev. 43, 865–880 (1978).

Gini index—United States. World Bank Open Data https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=US (2022).

Yitzhaki, S. Relative deprivation and the Gini coefficient. Q. J. Econ. 93, 321–324 (1979).

Veblen, T. The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions (MacMillan, 1899).

Clark, A. E. & D’Ambrosio, C. in Handbook of Income Distribution Vol. 2A (eds Atkinson, A. B. & Bourguignon, F.) (Elsevier, 2015).

Christakis, N. A. & Fowler, J. H. Social contagion theory: examining dynamic social networks and human behavior. Stat. Med. 32, 556–577 (2013).

Fowler, J. H. & Christakis, N. A. Cooperative behavior cascades in human social networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 5334–5338 (2010).

Gallo, E. & Yan, C. The effects of reputational and social knowledge on cooperation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3647–3652 (2015).

Milinski, M., Semmann, D. & Krambeck, H. J. Reputation helps solve the ‘tragedy of the commons’. Nature 415, 424–426 (2002).

Rand, D. G. & Nowak, M. A. Human cooperation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 413–425 (2013).

Bond, R. M. et al. A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization. Nature 489, 295–298 (2012).

Bentham, J. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (Clarendon Press, 1789).

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T. & Gosling, S. D. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 6, 3–5 (2011).

Huff, C. & Tingley, D. ‘Who are these people?’ Evaluating the demographic characteristics and political preferences of MTurk survey respondents. Res. Polit. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168015604648 (2015).

Hauser, D., Paolacci, G. & Chandler, J. in Handbook of Research Methods in Consumer Psychology (eds Kardes, F., Herr, P. M. & Schwarz, N.) (Routledge, 2019).

Gracia-Lazaro, C. et al. Heterogeneous networks do not promote cooperation when humans play a Prisoner’s Dilemma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12922–12926 (2012).

Shirado, H., Fu, F., Fowler, J. H. & Christakis, N. A. Quality versus quantity of social ties in experimental cooperative networks. Nat. Commun. 4, 2814 (2013).

Rand, D. G., Arbesman, S. & Christakis, N. A. Dynamic social networks promote cooperation in experiments with humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 19193–19198 (2011).

Rand, D. G., Nowak, M. A., Fowler, J. H. & Christakis, N. A. Static network structure can stabilize human cooperation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 17093–17098 (2014).

Chaudhuri, A. Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: a selective survey of the literature. Exp. Econ. 14, 47–83 (2011).

Pfeiffer, T., Tran, L., Krumme, C. & Rand, D. G. The value of reputation. J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 2791–2797 (2012).

Bolton, G. E., Katok, E. & Ockenfels, A. Cooperation among strangers with limited information about reputation. J Public Econ. 89, 1457–1468 (2005).

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz, N. & Stone, A. A. A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: the day reconstruction method. Science 306, 1776–1780 (2004).

Hardy, C. J. & Rejeski, W. J. Not what, but how one feels—the measurement of affect during exercise. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 11, 304–317 (1989).

Oswald, A. J. & Wu, S. Objective confirmation of subjective measures of human well-being: evidence from the USA. Science 327, 576–579 (2010).

Bates, D., Machler, M., Bolker, B. M. & Walker, S. C. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. LmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26 (2017).

Dreber, A., Rand, D. G., Fudenberg, D. & Nowak, M. A. Winners don’t punish. Nature 452, 348–351 (2008).

Gurerk, O., Irlenbusch, B. & Rockenbach, B. The competitive advantage of sanctioning institutions. Science 312, 108–111 (2006).

Zizzo, D. J. & Oswald, A. J. Are people willing to pay to reduce others’ incomes? Ann. d'Écon. Stat. 39–65 (2001).

Gachter, S. & Schulz, J. F. Intrinsic honesty and the prevalence of rule violations across societies. Nature 531, 496-+ (2016).

Cantril, H. The Pattern of Human Concerns (Rutgers Univ. Press, 1965).

van Deurzen, I., van Ingen, E. & van Oorschot, W. J. H. Income inequality and depression: the role of social comparisons and coping resources. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 31, 477–489 (2015).

Wilkinson, R. G. Health, hierarchy, and social anxiety. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 896, 48–63 (1999).

Kawachi, I. & Kennedy, B. P. Income inequality and health: pathways and mechanisms. Health Serv. Res. 34, 215–227 (1999).

Diener, E., Ng, W., Harter, J. & Arora, R. Wealth and happiness across the world: material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 99, 52–61 (2010).

Boyce, C. J., Brown, G. D. A. & Moore, S. C. Money and happiness: rank of income, not income, affects life satisfaction. Psychol. Sci. 21, 471–475 (2010).

Dowd, J. B., Simanek, A. M. & Aiello, A. E. Socio-economic status, cortisol and allostatic load: a review of the literature. Int. J. Epidemiol. 38, 1297–1309 (2009).

Haushofer, J. & Fehr, E. On the psychology of poverty. Science 344, 862–867 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support from Japan Science and Technology Agency (JPMJPR21R8), UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, the SEI Group CSR Foundation and the Murata Science Foundation (A.N.) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (N.A.C.). C. Muthappan, H. Ando and M. McKnight provided expert programming assistance and technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N. designed the project. A.N. and N.A.C. secured funding. A.N. and C.A.G. conducted the experiment. A.N., S.K.I. and C.A.G. conducted the statistical analyses. A.N., C.A.G., S.K.I. and N.A.C. analysed the findings and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.N. is a consultant to Vacan, Inc. and obtained an honorarium from Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., which had no role in the project. C.A.G. is an employee of 23andMe, which had no role in the project. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Mental Health thanks Osea Giuntella and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 The flow of our social network experiments.

A session consisting of a networked group lasted 15 rounds. The timing of reporting subjective well-being (SWB) was different before the actual game rounds started.

Extended Data Fig. 2 CONSORT participant flow diagram.

A, Experiment 1. B, Experiment 2.

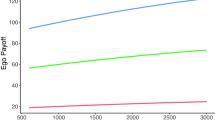

Extended Data Fig. 3 Trajectories of standardized and actual in-game units for the initially poor and rich subjects.

a–d. Experiment 1 (n = 570). e–h. Experiment 2 (n = 719). Lines with dots represent medians, light shading represents range between minimum and maximum, dark shading represents interquartile range (IQR).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Additional Analyses 1–8 and references.

Supplementary Code

R code.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Table 1

Raw result table.

Source Data Extended Data Table 2

Raw result table.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nishi, A., German, C.A., Iwamoto, S.K. et al. Status invisibility alleviates the economic gradient in happiness in social network experiments. Nat. Mental Health 1, 990–1000 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00159-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00159-0