Abstract

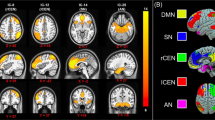

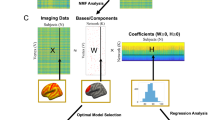

The dissociative subtype of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a distinct PTSD phenotype characterized by trauma-related dissociation, alongside unique patterns of functional connectivity. However, disparate findings across multiple scales of investigation have highlighted the need for a cohesive understanding of dissociative neurobiology. We took a step towards this goal by conducting one of the broadest region of interest (ROI)-to-ROI analyses performed on a PTSD population to date. In this retrospective study, we investigated resting-state functional MRI data collected from a total of 192 participants, 134 of whom were diagnosed with PTSD. Small functional connectivity differences (maximum effect size 0.27) were found between participants with PTSD and controls in the temporal regions and the right frontoparietal network. Participants with the dissociative subtype showed a markedly different pattern of widespread functional hyperconnectivity compared with controls (maximum effect size 0.46), spanning subcortical regions, sensorimotor and other intrinsic connectivity networks. Furthermore, analysis of latent dimensions underlying both ROI-to-ROI brain results and a range of behavioral and clinical measures identified three clinically relevant latent dimensions—two linked to dissociation and one linked to PTSD symptoms. These results advance our understanding of dissociative neurobiology, characterizing it as a divergence from normative small-world organization. These patterns of hyperconnectivity are thought to serve a compensatory function to preserve global brain functioning in participants experiencing trauma-related dissociation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$59.00 per year

only $4.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data supporting the results in this study are available within the paper and the accompanying Supplementary Information. The data use agreement governing the dataset used in this study restricts public sharing, and hence the dataset is not publicly available.

Code availability

The analyses used the standard SPM12 and CONN (version 21a) analysis pipelines and algorithms (for example, hierarchical clustering algorithm), and the standard MATLAB R2022a implementation of CCA, as described in the detailed Methods. No further custom code or algorithm was used in this study.

References

Lanius, R. A., Brand, B., Vermetten, E., Frewen, P. A. & Spiegel, D. The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: rationale, clinical and neurobiological evidence, and implications. Depress. Anxiety 29, 701–708 (2012).

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.BOOKS.9780890425596

Gidzgier, P. et al. The dissociative subtype of PTSD in women with substance use disorders: exploring symptom and exposure profiles. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 99, 73–79 (2019).

Steuwe, C., Lanius, R. A. & Frewen, P. A. Evidence for a dissociative subtype of PTSD by latent profile and confirmatory factor analyses in a civilian sample. Depress. Anxiety 29, 689–700 (2012).

Foote, B., Smolin, Y., Neft, D. I. & Lipschitz, D. Dissociative disorders and suicidality in psychiatric outpatients. J. Nervous Mental Dis. 196, 29–36 (2008).

Price, M., Kearns, M., Houry, D. & Rothbaum, B. O. Emergency department predictors of posttraumatic stress reduction for trauma-exposed individuals with and without an early intervention. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 82, 336–341 (2014).

Lebois, L. A. et al. Persistent dissociation and its neural correlates in predicting outcomes after trauma exposure. Am. J. Psychiatry 179, 661–672 (2022).

Vancappel, A. et al. Exploring strategies to cope with dissociation and its determinants through functional analysis in patients suffering from PTSD: a qualitative study. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 6, 100235 (2022).

Zoet, H. A., Wagenmans, A., van Minnen, A. & de Jongh, A. Presence of the dissociative subtype of PTSD does not moderate the outcome of intensive trauma-focused treatment for PTSD. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 9, 299–326 (2018).

Halvorsen, J. Ø., Stenmark, H., Neuner, F. & Nordahl, H. M. Does dissociation moderate treatment outcomes of narrative exposure therapy for PTSD? A secondary analysis from a randomized controlled clinical trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 57, 21–28 (2014).

Wolf, E. J. et al. A latent class analysis of dissociation and posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence for a dissociative subtype. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 69, 698–705 (2012).

Reinders, A. A. T. S. et al. Aiding the diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder: pattern recognition study of brain biomarkers. Br. J. Psychiatry 215, 536–544 (2019).

Roydeva, M. I. & Reinders, A. A. T. S. Biomarkers of pathological dissociation: a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 123, 120–202 (2021).

Bradley, R., Greene, J., Russ, E., Dutra, L. & Westen, D. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 214–227 (2005).

Stein, D. J., Ipser, J. C., Seedat, S., Sager, C. & Amos, T. Pharmacotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1, CD002795 (2006).

Ravindran, L. N. & Stein, M. B. Pharmacotherapy of PTSD: premises, principles, and priorities. Brain Res. 1293, 24–39 (2009).

Krystal, J. H. et al. It is time to address the crisis in the pharmacotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder: a consensus statement of the PTSD Psychopharmacology Working Group. Biol. Psychiatry 82, e51–e59 (2017).

Fox, M. D. & Greicius, M. Clinical applications of resting state functional connectivity. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 4, 19 (2010).

Greicius, M. Resting-state functional connectivity in neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 21, 424–430 (2008).

van de Ven, V. G., Formisano, E., Prvulovic, D., Roeder, C. H. & Linden, D. E. J. Functional connectivity as revealed by spatial independent component analysis of fMRI measurements during rest. Hum. Brain Mapp. 22, 165–178 (2004).

Akiki, T. J., Averill, C. L. & Abdallah, C. G. A network-based neurobiological model of PTSD: evidence from structural and functional neuroimaging studies. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 19, 81 (2017).

Jafri, M. J., Pearlson, G. D., Stevens, M. & Calhoun, V. D. A method for functional network connectivity among spatially independent resting-state components in schizophrenia. Neuroimage 39, 1666–1681 (2008).

Akiki, T. J. et al. Default mode network abnormalities in posttraumatic stress disorder: a novel network-restricted topology approach. Neuroimage 176, 489–498 (2018).

Barredo, J. et al. Neuroimaging correlates of suicidality in decision-making circuits in posttraumatic stress disorder. Front. Psychiatry 10, 44 (2019).

Barredo, J. et al. Network functional architecture and aberrant functional connectivity in post-traumatic stress disorder: a clinical application of network convergence. Brain Connect. 8, 549–557 (2018).

Lebois, L. A. M. et al. Large-scale functional brain network architecture changes associated with trauma-related dissociation. Am. J. Psychiatry 178, 165–173 (2021).

Thome, J. et al. Back to the basics: resting state functional connectivity of the reticular activation system in PTSD and its dissociative subtype. Chronic Stress 3, 247054701987366 (2019).

Thome, J. et al. Contrasting associations between heart rate variability and brainstem-limbic connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder and its dissociative subtype: a pilot study. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 16, 862192 (2022).

Harricharan, S. et al. fMRI functional connectivity of the periaqueductal gray in PTSD and its dissociative subtype. Brain Behav. 6, e00579 (2016).

Olivé, I. et al. Superior colliculus resting state networks in post-traumatic stress disorder and its dissociative subtype. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39, 563–574 (2018).

Terpou, B. A. et al. The threatful self: midbrain functional connectivity to cortical midline and parietal regions during subliminal trauma-related processing in PTSD. Chronic Stress 3, 247054701987136 (2019).

Terpou, B. A. et al. Moral wounds run deep: exaggerated midbrain functional network connectivity across the default mode network in posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 47, E56–E66 (2022).

Webb, E. K. et al. Acute posttrauma resting-state functional connectivity of periaqueductal gray prospectively predicts posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 5, 891–900 (2020).

Rabinak, C. A. et al. Altered amygdala resting-state functional connectivity in post-traumatic stress disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2, 62 (2011).

Sripada, R. K. et al. Altered resting-state amygdala functional connectivity in men with posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 37, 241–249 (2012).

Brown, V. M. et al. Altered resting-state functional connectivity of basolateral and centromedial amygdala complexes in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 351–359 (2014).

Nicholson, A. A. et al. The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: unique resting-state functional connectivity of basolateral and centromedial amygdala complexes. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 2317–2326 (2015).

Bluhm, R. L. et al. Alterations in default network connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder related to early-life trauma. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 34, 187–194 (2009).

Krause-Utz, A. et al. Amygdala and anterior cingulate resting-state functional connectivity in borderline personality disorder patients with a history of interpersonal trauma. Psychol. Med. 44, 2889–2901 (2014).

Reuveni, I. et al. Anatomical and functional connectivity in the default mode network of post-traumatic stress disorder patients after civilian and military-related trauma. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37, 589–599 (2016).

King, A. P. et al. Altered default mode network (DMN) resting state functional connectivity following a mindfulness-based exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in combat veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq. Depress. Anxiety 33, 289–299 (2016).

DiGangi, J. A. et al. Reduced default mode network connectivity following combat trauma. Neurosci. Lett. 615, 37–43 (2016).

Miller, D. R. et al. Default mode network subsystems are differentially disrupted in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2, 363–371 (2017).

Sheynin, J. et al. Associations between resting-state functional connectivity and treatment response in a randomized clinical trial for posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress. Anxiety 37, 1037–1046 (2020).

Nicholson, A. A. et al. Dynamic causal modeling in PTSD and its dissociative subtype: bottom-up versus top-down processing within fear and emotion regulation circuitry. Hum. Brain Mapp. 38, 5551–5561 (2017).

Daniels, J. K. et al. Switching between executive and default mode networks in posttraumatic stress disorder: alterations in functional connectivity. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 35, 258–266 (2010).

Ke, J. et al. Typhoon-related post-traumatic stress disorder and trauma might lead to functional integration abnormalities in intra- and inter-resting state networks: a resting-state fMRI independent component analysis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 48, 99–110 (2018).

Vuper, T. C., Philippi, C. L. & Bruce, S. E. Altered resting-state functional connectivity of the default mode and central executive networks following cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. Behav. Brain Res. 409, 113312 (2021).

Koch, S. B. J. et al. Aberrant resting-state brain activity in posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Depress. Anxiety 33, 592–605 (2016).

Stein, D. J. et al. Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from the world mental health surveys. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 302–312 (2013).

Lebois, L. A. M. et al. Persistent dissociation and its neural correlates in predicting outcomes after trauma exposure. Am. J. Psychiatry 179, 661–672 (2022).

Liddell, B. J. et al. Torture exposure and the functional brain: investigating disruptions to intrinsic network connectivity using resting state fMRI. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 37 (2022).

Fu, S. et al. Altered local and large-scale dynamic functional connectivity variability in posttraumatic stress disorder: a resting-state fMRI study. Front. Psychiatry 10, 234 (2019).

Dai, Y. et al. Altered dynamic functional connectivity associates with post-traumatic stress disorder. Brain Imaging Behav. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11682-023-00760-Y (2023).

Sullivan, T. P., Fehon, D. C., Andres-Hyman, R. C., Lipschitz, D. S. & Grilo, C. M. Differential relationships of childhood abuse and neglect subtypes to PTSD symptom clusters among adolescent inpatients. J. Trauma Stress 19, 229–239 (2006).

Dorahy, M. J., Middleton, W., Seager, L., Williams, M. & Chambers, R. Child abuse and neglect in complex dissociative disorder, abuse-related chronic PTSD, and mixed psychiatric samples. J. Trauma Dissociation 17, 223–236 (2016).

Nemeroff, C. B. Paradise lost: the neurobiological and clinical consequences of child abuse and neglect. Neuron 89, 892–909 (2016).

Daniels, J. K., Frewen, P., McKinnon, M. C. & Lanius, R. A. Default mode alterations in posttraumatic stress disorder related to early-life trauma: a developmental perspective. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 36, 56–59 (2011).

Seeley, W. W. et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 27, 2349–2356 (2007).

Zanto, T. P. & Gazzaley, A. Fronto-parietal network: flexible hub of cognitive control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 602–603 (2013).

Scolari, M., Seidl-Rathkopf, K. N. & Kastner, S. Functions of the human frontoparietal attention network: evidence from neuroimaging. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 1, 32–39 (2015).

Cisler, J. M., Scott Steele, J., Smitherman, S., Lenow, J. K. & Kilts, C. D. Neural processing correlates of assaultive violence exposure and PTSD symptoms during implicit threat processing: a network-level analysis among adolescent girls. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 214, 238–246 (2013).

Lanius, R. A., Frewen, P. A., Tursich, M., Jetly, R. & McKinnon, M. C. Restoring large-scale brain networks in PTSD and related disorders: a proposal for neuroscientifically-informed treatment interventions. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 6, 27313 (2015).

Bao, W. et al. Alterations in large-scale functional networks in adult posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 131, 1027–1036 (2021).

Falconer, E. et al. The neural networks of inhibitory control in posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 33, 413–422 (2008).

DeGutis, J. et al. Posttraumatic psychological symptoms are associated with reduced inhibitory control, not general executive dysfunction. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 21, 342–352 (2015).

de Bellis, M. D. et al. Superior temporal gyrus volumes in maltreated children and adolescents with PTSD. Biol. Psychiatry 51, 544–552 (2002).

Olson, I. R., Plotzker, A. & Ezzyat, Y. The enigmatic temporal pole: a review of findings on social and emotional processing. Brain 130, 1718–1731 (2007).

Daniels, J. K., Lamke, J. P., Gaebler, M., Walter, H. & Scheel, M. White matter integrity and its relationship to PTSD and childhood trauma—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 30, 207–216 (2013).

Koch, S. B. J. et al. Decreased uncinate fasciculus tract integrity in male and female patients with PTSD: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 42, 331–342 (2017).

Costanzo, M. E. et al. White matter microstructure of the uncinate fasciculus is associated with subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and fear potentiated startle during early extinction in recently deployed service members. Neurosci. Lett. 618, 66–71 (2016).

Gross, C. G. Representation of visual stimuli in inferior temporal cortex. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 335, 3–10 (1992).

Conway, B. R. The organization and operation of inferior temporal cortex. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 4, 381 (2018).

Polak, A. R., Witteveen, A. B., Reitsma, J. B. & Olff, M. The role of executive function in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 141, 11–21 (2012).

Swart, S., Wildschut, M., Draijer, N., Langeland, W. & Smit, J. H. Dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder or PTSD with comorbid dissociative disorders: comparative evaluation of clinical profiles. Psychol. Trauma 12, 38–45 (2020).

Nijenhuis, E. R. S. Ten reasons for conceiving and classifying posttraumatic stress disorder as a dissociative disorder. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 1, 47–61 (2017).

Reinders, A. A. T. S. & Veltman, D. J. Dissociative identity disorder: out of the shadows at last? Br. J. Psychiatry 219, 413–414 (2021).

Viessmann, O. & Polimeni, J. R. High-resolution fMRI at 7 tesla: challenges, promises and recent developments for individual-focused fMRI studies. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 40, 96–104 (2021).

Edlow, B. L. et al. Neuroanatomic connectivity of the human ascending arousal system critical to consciousness and its disorders. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 71, 531–546 (2012).

Schlumpf, Y. R. et al. Dissociative part-dependent biopsychosocial reactions to backward masked angry and neutral faces: an fMRI study of dissociative identity disorder. Neuroimage Clin. 3, 54–64 (2013).

Schlumpf, Y. R. et al. Dissociative part-dependent resting-state activity in dissociative identity disorder: a controlled FMRI perfusion study. PLoS ONE 9, e98795 (2014).

Blake, D. D. et al. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J. Trauma Stress 8, 75–90 (1995).

Weathers, F. W. et al. The clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychol. Assess. 30, 383–395 (2018).

Nicholson, A. A. et al. Classifying heterogeneous presentations of PTSD via the default mode, central executive, and salience networks with machine learning. Neuroimage Clin. 27, 102262 (2020).

Nicholson, A. A. et al. A randomized, controlled trial of alpha-rhythm EEG neurofeedback in posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary investigation showing evidence of decreased PTSD symptoms and restored default mode and salience network connectivity using fMRI. Neuroimage Clin. 28, 102490 (2020).

Harricharan, S. et al. Sensory overload and imbalance: resting-state vestibular connectivity in PTSD and its dissociative subtype. Neuropsychologia 106, 169–178 (2017).

Nicholson, A. A. et al. Intrinsic connectivity network dynamics in PTSD during amygdala downregulation using real-time fMRI neurofeedback: a preliminary analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39, 4258–4275 (2018).

Bernstein, D. P. et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 27, 169–190 (2003).

Beck, A. T., Guth, D., Steer, R. A. & Ball, R. Screening for major depression disorders in medical inpatients with the beck depression inventory for primary care. Behav. Res. Ther. 35, 785–791 (1997).

Briere, J., Weathers, F. W. & Runtz, M. Is dissociation a multidimensional construct? Data from the Multiscale Dissociation Inventory. J. Trauma Stress 18, 221–231 (2005).

Gratz, K. L. & Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26, 41–54 (2004).

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. & Nieto-Castanon, A. CONN: a functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect. 2, 125–141 (2012).

Ashburner, J. & Friston, K. J. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage 26, 839–851 (2005).

Desikan, R. S. et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 31, 968–980 (2006).

Tzourio-Mazoyer, N. et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage 15, 273–289 (2002).

Smith, S. M. et al. A positive-negative mode of population covariation links brain connectivity, demographics and behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1565–1567 (2015).

Lin, H. Y. et al. Brain–behavior patterns define a dimensional biotype in medication-naïve adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychol. Med. 48, 2399–2408 (2018).

Tung, Y. H. et al. Whole brain white matter tract deviation and idiosyncrasy from normative development in autism and ADHD and unaffected siblings link with dimensions of psychopathology and cognition. Am. J. Psychiatry 178, 730–743 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the individuals who participated, as well as Homewood Health in Guelph, Ontario, Canada, who facilitated referrals. We are also grateful to our dedicated research and clinical team, without whom we could not have done this work. This work was supported by infrastructure funds from the Canada Foundation for Innovation Grant (J.T.; grant number 31724) and Lawson Health Research Institute, as well as operating funds from the Canadian Institute of Military and Veteran Health Research, Green Shield Canada, the Centre of Excellence on PTSD, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (M.C.M. and R.A.L.; grant number 148784). R.A.L. is supported by the Harris-Woodman Chair in Psyche and Soma at Western University, and M.C.M. is supported by the Homewood Chair in Mental Health and Trauma at McMaster University. S.B.S. and B.A.T. are supported by Mitacs Elevate funding, partnered generously by the Homewood Research Institute in Guelph, Ontario, Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B.S.: conceptualization, methodology, data collection and curation, data analysis and writing. B.A.T.: data collection and curation, data analysis and writing. M.D.: data curation and methodology. J.T.: methodology. P.F.: methodology. M.C.M.: supervision, funding acquisition. R.A.L.: conceptualization, data collection and curation, supervision, methodology, funding acquisition and writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Mental Health thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 and Tables 1–3.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 1 and 2

Statistical source data containing unprocessed two-sided contrast between the PTSD group and controls, used for the visualization in Figs. 1a and 2a; statistical source data containing unprocessed two-sided contrast between the PTSD + DS group and controls, used for the visualization in Figs. 1b and 2b.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shaw, S.B., Terpou, B.A., Densmore, M. et al. Large-scale functional hyperconnectivity patterns in trauma-related dissociation: an rs-fMRI study of PTSD and its dissociative subtype. Nat. Mental Health 1, 711–721 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00115-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-023-00115-y

This article is cited by

-

Disentangling sex differences in PTSD risk factors

Nature Mental Health (2024)

-

Brain functional connectivity abnormalities in trauma-related dissociation

Nature Mental Health (2023)