Abstract

The understanding and manipulation of microbial communities toward the conversion of lignocellulose and plastics are topics of interest in microbial ecology and biotechnology. In this study, the polymer-degrading capability of a minimal lignocellulolytic microbial consortium (MELMC) was explored by genome-resolved metagenomics. The MELMC was mostly composed (>90%) of three bacterial members (Pseudomonas protegens; Pristimantibacillus lignocellulolyticus gen. nov., sp. nov; and Ochrobactrum gambitense sp. nov) recognized by their high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs). Functional annotation of these MAGs revealed that Pr. lignocellulolyticus could be involved in cellulose and xylan deconstruction, whereas Ps. protegens could catabolize lignin-derived chemical compounds. The capacity of the MELMC to transform synthetic plastics was assessed by two strategies: (i) annotation of MAGs against databases containing plastic-transforming enzymes; and (ii) predicting enzymatic activity based on chemical structural similarities between lignin- and plastics-derived chemical compounds, using Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System and Tanimoto coefficients. Enzymes involved in the depolymerization of polyurethane and polybutylene adipate terephthalate were found to be encoded by Ps. protegens, which could catabolize phthalates and terephthalic acid. The axenic culture of Ps. protegens grew on polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) nanoparticles and might be a suitable species for the industrial production of PHAs in the context of lignin and plastic upcycling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, the energy transition from fossil to renewable resources and the degradation and recycling of plastics are topics of global concern [1, 2]. Lignocellulose is one of the main renewable resources used for the production of biofuels, bioplastics, and other commodity chemicals [3, 4]. In biorefineries, one of the major bottlenecks is the low efficiency in the release of sugar monomers from agricultural residues [5]. Therefore, the use of enzyme cocktails, produced by mixed microbial cultures, has been proposed as an alternative to improve this saccharification process [6]. In this context, the design and characterization of lignocellulolytic microbial consortia has received increasing attention during the last decade [7,8,9,10]. These microbial communities can be assembled by two main approaches [11]: (1) the “top-down” enrichment, which consists of the selection of nature-derived populations with the capacity to grow in a minimal medium containing plant biomass as the sole carbon source [12, 13]; and (2) the “bottom-up” strategy, where microbial axenic strains are mixed in different proportions and types to produce a synthetic community [14, 15]. The outcomes of these two approaches are lignocellulolytic microbial consortia that can be characterized by different meta-omics approaches [8, 16,17,18], In some cases, metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) could be retrieved and analyzed from these consortia [19, 20]. In the “top-down” approach, many factors can shape the final selected microbial consortia, including the starting inoculum [21] and the carbon source [22]. In many cases, the microbial communities selected by this enrichment approach are still highly complex, with hundreds of species coexisting in the same flask [16]. These species can interact by synergism, competition, and commensalism, having preferences for certain niches that allow them to coexist in a highly dynamic environment [23]. Inspired by Kang et al. [24], a method to select the minimal number of bacterial species that are able to grow on lignocellulose was recently developed by our research group [13].

Lignocellulolytic microbial communities harbor a huge potential to deconstruct cellulose, xylan, and lignin [25]. Recently, specific lignin-degrading microbial consortia have been developed [26, 27]. Lignin is a heterogeneous aromatic plant polymer formed via radical coupling reactions involving p-coumaryl, coniferyl, and sinapyl alcohols, linked by C–C and C–O bonds [28]. Interestingly, these are the same type of bonds found in the backbone of some fossil- (e.g., polyethylene terephthalate (PET)) and bio-based plastics (e.g., polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs)). Therefore, it has been suggested that microbes thriving on lignin (or lignocellulose) could have an enormous enzymatic potential to depolymerize/catabolize plastics and their derived chemical compounds [29, 30]. Particularly, Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Paenibacillus species, which are found in different lignocellulose-degrading microbial communities [13, 21, 22], could have the capacity to metabolize PET and/or polypropylene [31, 32]. Despite the structural similarities of some plastics and plant-derived polymers, the potential for the transformation of fossil and bio-based plastics by lignocellulose-degrading microbial consortia remains underexplored. The main goal of the current study was to elucidate the polymer-transforming capacity of a minimal and effective lignocellulolytic microbial consortium (hereafter MELMC) [13]. We hypothesized that the MELMC members with the capacity to catabolize lignin, and its derived aromatic compounds, might as well have a big potential to transform fossil- and bio-based plastics. In this study, PacBio-HiFi metagenome sequencing allowed the complete reconstruction of circular and high-quality genomes (i.e., MAGs) of the three most abundant MELMC members. Notably, two of them were analyzed and cataloged as novel bacterial taxa. Through combined use genomic databases and wet-lab experiments, we predicted the functional role of each MELMC member and their capacity to degrade plant polymers, catabolize lignin and transform plastics, as well as their derived chemical compounds.

Materials and methods

Construction of a minimal and effective lignocellulolytic bacterial consortium

In 2021, Díaz-García et al. [13] designed and performed an innovative “top-down” strategy to select a MELMC from Colombian Andean Forest soils (Gámbita, Santander). Briefly, the “dilution-to-stimulation” approach was set up to promote the growth of lignocellulose-degrading microorganisms through cultivation under aerobic and mesophilic conditions using a mixture of three agricultural residues (sugarcane bagasse, corn stover, and rice husk) as the sole carbon source. Afterward, the authors executed the “dilution-to-extinction” phase to reduce the microbial diversity through an array of serial dilutions, aiming to select the MELMC. Bacterial 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing was performed to characterize the MELMC, which was the starting point of our current study.

Isolation and characterization of axenic cultures from the MELMC

The isolation of bacterial pure cultures from the MELMC was done on R2A, Cetrimide, and LB agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Serial dilutions of the MELMC were done in sterile 0.85% NaCl solution, and 100 μl of each dilution (10−6–10−8) were spread on the surface of solid media. Morphologically different colonies were selected, purified, and preserved at −80 °C in LB broth with glycerol (20% v/v). Genomic DNA from pure cultures was extracted using the DNeasy UltraClean® Microbial Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the instruction of the manufacturer. Bacterial 16S rRNA genes were amplified using primers 27F and 1492R. PCR reactions were done in a 50 μl reaction mixture containing 1X OneTaq® DNA Polymerase Quick-Load Master Mix (NEB, Massachusetts, United States) with standard buffer, 0.2 μM of each primer and 100–500 ng of bacterial DNA. The PCR settings are described by Jiménez et al. [12]. PCR products were purified and then sequenced by Sanger Technology using the primer 27F in Macrogen Company (Seoul, Korea). High-quality sequences for each axenic culture were taxonomically affiliated using BLASTn against the NCBI GenBank database (accessed in November 2021).

Whole-metagenome sequencing and reconstruction of bacterial genomes

Total genomic DNA extracted from the MELMC was used for whole-metagenome sequencing using PacBio Technology. A SMRTbell® template library was prepared according to the instructions from Pacific Biosciences (Menlo Park, CA, United States), following the procedure and checklist—preparing 10 kb library using SMRTbell® Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 for metagenomics shotgun sequencing. Libraries were sequenced on the SequelIIe Instrument, at the Leibniz Institute DSMZ, taking one 30 h movie per SMRT cell. For each sample, 1.33 SMRT cells were run. The raw sequence reads obtained were assembled using the software Flye v2.8 [33] with the metagenome and --pacbio-hifi options. Circular contigs with a length greater than 1.5 Mbp were retained for further analysis. CheckM v1.0.13 [34] was used with the lineage_wf option to assess the quality, completeness, and contamination of the selected contigs. The number of mapped reads from each MAG was calculated using Bowtie v2.3.5 [35]. Curation and structural annotation of MAGs based on rRNAs genes (e.g., 5S, 16S, and 23S) and the rpoB gene was carried out with the DFAST v1.2.6 pipeline [36]. The quality assessment percentages of MAGs (i.e., completeness and contamination) were compared to those established by Bowers et al. [37]. The webserver CGView [38] was used to set up a circular map analysis of each MAG, including identification of their genomic islands and phage sequences, which were retrieved using Island Viewer 4 [39] and PHASTER [40] (accessed in January 2022), respectively.

Taxonomic/phylogenomic placement of the metagenome-assembled genomes

The webserver JSpecies was used to determine a genome distance metric based on the average nucleotide identity (ANI) against related bacterial species [41]. In addition, average amino acid identity (AAI) against closely related genomes was calculated using the Microbial Genomes Atlas (MiGA) v1.2.6.0 [42] against the TypeMat database release r2022-04 [43]. The assessment of novel taxa was considered the ANI and AAI thresholds proposed by Konstantinidis et al. [44] (e.g., new species less than 95% ANI with its closest relatives and a new genus less than 65% AAI with related genera). In addition, the high-quality MAGs were uploaded to the Type (Strain) Genome Server (TYGS) in order to get additional genome features, such as digital DNA–DNA Hybridization (dDDH) and other ANI values [45]. Using the TGYS, phylogenetic comparisons (based on bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences) and genome/proteome-based phylogenomic analysis (using Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny method (GBDP)) were carried out [46, 47]. Additional genomic features, including length, G+C content, G-C and A-T skews, protein counts, coding density, and 16S rRNA genes, were obtained by both MiGA and TYGS. The similarity among 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained from the bacterial isolates (~800 bp), retrieved MAGs (~1500 bp), and amplicon-sequence variants (ASVs) (~300 bp), previously obtained by Díaz-García et al. [13] was assessed by a multiple alignment using ClustalW and phylogenetic analysis (Neighbor-Joining, using p-distance method) conducted using the software MEGAX v10.2.6 [48].

Functional annotation of the metagenome-assembled genomes

Different strategies were used to annotate enzymes associated with carbohydrates, lignin, lipids, and plastic transformation within the MAGs. Annotation of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) was performed using the standalone version of dbCAN2 tool v10 [49]. Results were displayed through a heatmap elaborated using the superheat package in R studio software [50]. Data were normalized by the total number of genes associated with each CAZyme family within each MAG, and compared to different reported bacterial genomes. Then, lignin-transforming enzymes were selected based on Diaz-Garcia et al. [51], and the respective genes (i.e., KO identifiers) were searched by the annotation carried out using the RAST [52] and BlastKOALA servers [53]. Finally, the MAGs were aligned using DIAMOND v0.9 [54] against the Plastics Microbial Biodegradation Database (PMBD) [55], and annotated with the PlasticDB [56], the PHA Depolymerase Engineering [57], and the Lipase Engineering [58] databases, setting a minimum amino acid identity cutoff of 50%.

Construction of a tripartite graph for predicting plastic-transforming enzymes

Information about lignin-transforming enzymes and lignin-derived chemical compounds (LDCC) were retrieved from the eLignin [59] and KEGG databases. Moreover, plastic-derived chemical compounds (PDCC) were selected using the PMBD database [55]. The Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) format of each chemical compound (i.e., LDCC and PDCC) was retrieved using the PubChem database [60]. Based on LDCC and PDCC SMILES, the molecular fingerprints and Tanimoto coefficient [61] for pairs of chemical compounds were calculated using the python RDkit library [62], resulting in a similarity matrix. Chemical compounds with a similarity value greater than or equal to 65% were selected to build an unweighted undirected tripartite graph, using the R Igraph library [63], in which nodes of each partition represent the PDCC connected to the most similar LDCC, and the enzymes that could be involved into the catalysis of the latter, which could by association have an activity of the PDCC.

Growth of Ps. protegens using polyhydroxyalkanoates nanoparticles

Given that chemical structure in PHAs can differ and affect the enzymatic catalysis, the ability of Ps. protegens (MAG1) to grow on nanoparticles of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) (obtained from Sigma Aldrich – CAS 29435-48-1) and polyhydroxyoctanoate (PHO – 98% purity) as the sole carbon source was tested. Briefly, 100 μl of an overnight culture of the Ps. protegens (in LB liquid medium) were inoculated in a 100-ml Erlenmeyer flask that contained 20 ml of Minimal-Medium M9 (MM), composed of (g/l) 3 KH2PO2, 7 (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 NaCl, 1 (NH4)Cl and supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 20 µl of 1000X trace element solution [64]. In addition, the liquid MM medium contained a final concentration of 0.05 mg/ml PHB or 0.08 mg/ml PHO nanoparticles (emulsion in distilled water) that were added after 20 min UV (254 nm wavelength) sterilization. For the preparation of nanoparticles (100–500 µM), we follow the methodology reported by Schirmer et al. [65]. The controls used for this experiment were: MM + PHB, MM + PHO, both without bacterial inoculum and MM + bacterial inoculum (initial optical density (OD) at 600 nm of 0.03), without PHAs nanoparticles. Duplicate cultures were incubated at 30 °C and 200 rpm. The OD600nm was measured at 48 and 144 h after incubation. Once the cultures reached OD600nm > 1, 100 µl of the bacterial culture were transferred to a fresh liquid MM + PHB/O nanoparticles (pass 2), and then incubated in the above conditions.

Results

Features of the metagenome-assembled genomes obtained from the MELMC

For PacBio-HiFi metagenome sequencing, three biological replicates from the MELMC were selected. For each replicate, around 2.7 million reads were obtained with sizes of 6–7 kb. After merging and assembling all sequence reads, three complete circular and high-quality genomes with sizes of 6.98, 5.26, and 2.52 Mbp were obtained (Fig. 1). The three MAGs recovered showed values for completeness and contamination of 99% and 1.4% (MAG1); 98% and 0.7% (MAG5); 90 and 0% (MAG4). Other MAG features (e.g., mol% GC, coding density, number of 16S rRNA copies, and proteins) can be found in Table 1. Interestingly, some MAGs regions were associated with prophage sequences (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

Circles from outside inwards represent: Circle 1. Protein-coding genes (CDS) in purple for MAG1 (Pseudomonas protegens), green for MAG5 (Pristimantibacillus lignocellulolyticus), and blue for MAG4 (Ochrobactrum gambitense). Circle 2. Genomic islands in red. Circle 3. Ribosomal RNA genes in orange. Circle 4. Phage sequences in green and pointed out with an arrow. Circle 5. GC content in black.

Novel bacterial taxa found in the MELMC

To determine the taxonomic origin and phylogenomic placement of the three high-quality and circularized MAGs, different approaches and genomic metrics were used. Regarding MAG1, all metrics highly support its affiliation to Pseudomonas protegens. On the other hand, MAG4 and MAG5 did not have ANI values (between 68 and 90%) or dDDH percentages (≤41%) indicative of classification in currently named species. The AAI percentages indicated that MAG4 could be closely related to Ochrobactrum teleogrylli (95.0%) and MAG5 distantly related to Paenibacillus pinisoli (64.6%) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The taxonomic affiliations of MAG5 and MAG4 to Paenibacillus and Ochrobactrum genera, respectively, were supported by 16S rRNA phylogeny (Supplementary Fig. S1). In the case of MAG5, a phylogenomic tree based on whole-proteome data and GBDP distances revealed a poorly supported clade corresponding to a species cluster, including the type strains Pa. endophyticus, Pa. pinisoli, Pa. paeoniae, Pa. nanensis, and Pa. algarifonticola (Fig. 2). However, MAG5 showed lower values of ANIm (87.7% with Pa. popilliae) and AAI (64.6% with Pa. pinisoli), suggesting that it belongs to a novel genus within the order Caryophanales (“Bacillales”; p value: 0.0018, highest taxonomic rank with p value ≤0.5 based on MiGA) (Table 1). Following the rules of the SeqCode, this genus is named here Pristimantibacillus (Pris.ti.man.ti.ba.cil’lus) (N.L. masc. n. Pristimantis, from Pristimantis natural reserve, where soil samples were taken to select the minimal lignocellulolytic bacterial consortium including a member of this taxon; L. masc. n. bacillus, little staff, a rod; N.L. masc. n. Pristimantibacillus, a rod-shaped cell from Pristimantis natural reserve); a genus established on the basis of MiGA taxonomic novelty analyses, AAI, dDDH, 16S rRNA gene phylogenetic reconstruction, and phylogenomic analyses and is classified as a member of the Paenibacillaceae family (p value: 0.221, MiGA). The type species of the genus is Pristimantibacillus lignocellulolyticus (lig.no.cel.lu.lo.ly’ti.cus) (N.L. neut. n. lignocellulosum, lignocellulose; N.L. masc. adj. lyticus, (from Gr. masc. adj. lytikos) able to dissolve; N.L. masc. adj. lignocellulolyticus, capable of degrading lignocellulose as part of a lignocellulolytic bacterial consortium). The species is established on the same basis as the genus and the type material is the MAG5, deposited in NCBI assembly with accession number CP097899. As for MAG4, MiGA results suggested that it belongs to a novel species within the genus Ochrobactrum (p value: 0.061), for which the name Ochrobactrum gambitense (gam.bi.ten’se) (N.L. neut. adj. gambitense, of Gambita, the municipally where soil samples were taken to select the minimal lignocellulolytic bacterial consortium "MELMC) is proposed. The species is established on the basis of MiGA taxonomic novelty analysis, and the type material is the MAG4, deposited in NCBI assembly with accession number CP098020. The names proposed here have been submitted to the SeqCode registry with accession https://seqco.de/r:xwx6hrsf.

The figure was retrieved from Type Strain Genome Server (TYGS). Tree inferred with FastME v2.1.6.1 from whole-proteome-based GBDP distances. The branch lengths are scaled via GBDP distance formula d5. Branch values are GBDP pseudo-bootstrap support values >60% from 100 replications, with average branch support of 91.9%. The tree was midpoint-rooted.

Comparison of 16S rRNA gene sequences from bacterial isolates, MAGs and ASVs

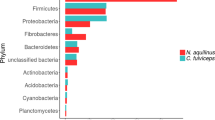

A total of 19 bacterial pure cultures, with different colony morphologies, were recovered from the MELMC. From those, 17 isolates were taxonomically classified using their 16S rRNA gene sequences. Only two different species were identified (twelve isolates belonged to Ps. protegens and five to Bacillus subtilis) (Supplementary Table 3). Previously, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing analysis revealed that the MELMC was mostly composed of two species (Pseudomonas sp. and Paenibacillus sp.), with additional ASVs found in very low abundance (<0.01%) [13]. To determine if the MAGs match one of the recovered axenic cultures, and to compare them with the reported ASVs, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using all the 16S rRNA gene sequences (Fig. 3). The results indicated that MAG1 was recovered as a pure culture (type strain 5 M). Based on total metagenomic mapped reads, the relative abundance of MAG1 was 74% compared to 38.6% obtained in the 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing analysis. The complete 16S rRNA gene sequence from MAG5 was highly similar to ASV1a (with a relative abundance of 22.3%). The MAG5 was the second most abundant MELMC member (12.3%). Moreover, MAG4, with a relative abundance of 6.2%, showed high similarity with two reported ASVs found at very low abundance (<0.016%). MAG4 and MAG5 were not associated with any bacterial isolate. However, an axenic culture of B. subtilis was recovered, and it showed similarity with an ASV0 found at very low abundance (0.015%) within the MELMC (Fig. 3).

A copy of the 16S rRNA gene was randomly selected from each MAG to build the phylogenetic tree. Bootstrap tests (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches and evolutionary distances are in units of the number of base differences per site. At right, we display the colonies of the recovered bacterial axenic cultures (Pseudomonas protegens and Bacillus subtilis).

Identification of CAZymes involved in lignocellulose degradation

The CAZyme profile associated with deconstruction of lignocellulose [8, 17] was analyzed for the three MAGs obtained from the MELMC, and compared with 30 other closely related bacterial genomes (Fig. 4). The results showed that Paenibacillus species contains the highest potential to deconstruct plant polysaccharides due to the high abundance and diversity of many glycoside hydrolases (GHs) families. In particular, MAG5 contained a higher number of genes to deconstruct cellulose (e.g., families GH5, GH8, GH9, and AA10) and xylan (e.g., families GH10, GH11, GH30, GH43, GH51, and GH67) compared to MAG1 and MAG4. Clearly, Pseudomonas and Ochrobactrum species had a smaller potential to deconstruct plant polysaccharides. Within the Pseudomonas species, there was a common potential for the degradation of oligosaccharides and pectin, which is reflected by the presence of families GH3 and GH13. Interestingly, MAG1 and MAG4 contain genes from families AA3 (involved in the oxidation of alcohols or carbohydrates) and AA6 (involved in the catabolism of aromatic compounds). In addition, MAG5 contained genes of the AA1 family (i.e., laccases) (Fig. 4). These former AA families could be involved in lignin transformations.

Comparison was performed using the CAZyme profiles of 30 close-bacterial genomes. Heatmaps were constructed using normalized values (by number of hits per genome). The labels within squares represent the type of polymers where enzymes could act: O oligosaccharides, C cellulose, L lignin, X xylan, P pectin. Asterisks represent CAZy families uniquely found in the MAGs from the MELMC.

Lignin catabolism profile of the MELMC

We explored the presence and abundance of 92 types of proteins involved in the transformation of lignin [51] within the three MAGs. In total 66, 21, and 22 genes encoding 40 types of lignin-transforming enzymes were found within MAG1, MAG5, and MAG4, respectively (Supplementary Table 4). Interestingly, MAG1 (Ps. protegens) shows the largest potential to depolymerize lignin, reflected by the presence of genes encoding glutathione S-transferases (EC 2.5.1.18), catalases (EC 1.11.1.6), and glutathione peroxidases (EC 1.11.1.9). These enzymes could also be expressed in response to oxidative stress. In particular, MAG1 encodes genes involved in the catabolism of lignin monomers through the beta-ketoadipate (e.g., pca genes) and protocatechuate cleavage pathways (e.g., lig and mhp genes). In addition, genes involved in catechol (catABC) and vanillin (vanAB genes) catabolism were also found in MAG1 (Supplementary Table 4). Based on KEGG database and RAST annotation, other regulators (PerR and CtsR) and genes (e.g., the mhqA that encodes a hydroquinone-specific dioxygenase) involved in thiol-specific oxidative stress response and associated with the consumption of aromatic compounds, such as 2-methylhydroquinone or catechol, were found in Pr. lignocellulolyticus (MAG5).

Potential of the MELMC to transform plastics and its derived compounds

Based on the functional annotation using PMBD and PlasticDB databases, it was observed that MAG1 contains genes associated with the transformation of polyurethane (PU), polybutylene adipate terephthalate (PBAT), and low-density polyethylene (LDPE) (Table 2). MAG4 showed a genomic capacity to produce phthalate dioxygenases. In addition, MAG1 and MAG4 have the genomic potential to produce 3HV-dioxygenases, probably involved in the intracellular metabolism of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV). Based on the structural features (using SMILES) between LDCC and PDCC, a method to quantify similarity using Tanimoto coefficients was developed. Here, 43 PDCC were pairwise compared with each of the 70 LDCC (Supplementary Table 5). From this analysis, we could predict which lignin-transforming enzymes could be active on PDCC. The tripartite network (Fig. 5) displayed three main cases: (i) PDCC that are similar to one LDCC, which in turn is catabolized by a single enzyme, (e.g, monomethyl phthalate); (ii) a PDCC similar to two or more LDCC, which are substrates for different enzymes (e.g., 3,4-dihydroxyphtalate); (iii) two PDCC that are similar to one LDCC, catabolized by a single enzyme (e.g., 3-hydroxyvalerate and 3-hydroxybutyric acid). Finally, the tripartite network showed that Ps. protegens (MAG1) is expected to catabolize monomers from PHBs (e.g., PHB and PHBV) and PET (e.g., terephthalic acid), and other chemical compounds commonly used as plasticizers (e.g., phthalates). Finally, MAG4 encodes two enzymes that could transform 3,4 hydroxyphthalate (4-hydroxybenzoate 3-monooxygenase and salicylate 1-hydroxylase), an intermediate compound in phthalates degradation (Fig. 5).

Colored circles indicate from left to right: plastic-derived chemical compounds (PDCC) (blue), lignin-derived chemical compounds (LDCC) (yellow), and lignin-catabolizing enzymes (red). Black edges represent SMILES similarity values (based on Tanimoto coefficients) greater than 65%. Red edges connect lignin-derived substrates with enzymes that use them as substrate. The number of genes found in each MAG is indicated in squared brackets.

Catabolism and production of polyhydroxyalkanoates in Ps. protegens (MAG1)

It was observed that Ps. protegens (i.e., strain M5; MAG1) can grow on PHB and PHO as sole carbon sources, reaching an average OD600nm of 0.7 (PHB) and 0.6 (PHO) after 48 h of incubation in the first pass. Upon transfer to fresh media containing nanoparticles (2nd transfer), Ps. protegens grew faster, showing OD600nm average values of 1.0 and 2.0 for PHB and PHO, respectively, compared to the first batch at the same incubation time (Fig. 6). When looking into its genomic potential, MAG1 encode some extracellular lipases predicted to depolymerize PHAs (Supplementary Table 6). Furthermore, several genes associated with PHA catabolism were found in MAG1, including an intracellular PHO depolymerase (encoded by phaZ) (Fig. 6), and others encoding enzymes involved in fatty acids (PHA-related substrates) metabolism through β-oxidation pathway. For instance, acyl-CoA synthetase (EC 6.2.1.3), acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (EC 1.3.1.8), enoyl-CoA hydratase (EC 4.2.1.17), 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.157), and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (EC 2.3.1.16). Moreover, a cluster of genes (phaC1ZC2D), well conserved among the medium-chain length-PHA (mcl-PHA) producer strains like Ps. putida KT2440, was found within MAG1. The cluster is composed of phaC1 and phaC2 genes encoding two class II synthases, phaD encoding a TetR-like transcriptional regulator; and phaI and phaF encoding structural proteins known as phasins that are highly relevant in the production and regulation of PHAs (Fig. 6).

In the left-up, we display the growth (assessed by OD600nm) values obtained on PHB and PHO as the sole carbon source; B and O are controls without bacterial inoculum and Pp is the controls without PHAs. Cluster of genes (arrows depending on their transcription direction) associated with PHA synthesis (and found in MAG1) are at the figure bottom. In right-middle, we display how plastic monomers or plasticizers can be metabolized thought protocatechuate pathways allowing the growth of Ps. protegens and synthesis of PHAs. These PHAs can be catabolized and synthetized through fatty acid beta-oxidation pathway.

Discussion

The selection and design of plant biomass-degrading microbial consortia (PBDC) has been traditionally carried out to reach three main goals: (i) to reduce the complexity of wild-type communities, aiming for a better understanding of the ecology, enzymology, and dynamics behind lignocellulose transformation [23]; (ii) to design a microbial platform for the production of enzyme cocktails useful in biorefineries [17]; and (iii) to produce commodity chemicals, biopolymers, biofuels or pharmaceutical compounds in a consolidated bioprocess [66]. For the first goal, minimal and effective PBDC have been designed using the “bottom-up” strategy [67]. For instance, a tripartite fungal-bacterial consortium has been exhaustively explored in different studies [15, 68, 69]. In contrast, information and knowledge on the selection of minimal PBDC using the “top-down” approach is limited. In this regard, we have developed an innovative enrichment method to select a MELMC from Colombian Andean Forest soils [13].

Metagenomic surveys have allowed us to extract and analyze meaningful information about lignocellulolytic microbial communities from different natural environments [70, 71]. Recently, genome-resolved metagenomics has been used to characterize different polymer-degrading consortia [20, 72]. In this regard, Peng et al. [73] found 719 high-quality MAGs (unique at the species level) from PBDC retrieved from goat guts. In our study, the first relevant observation was that the MELMC is composed mostly of three species (Fig. 1), instead of two as 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing showed [13]. The relative abundance of the three high-quality MAGs (MAG1, MAG4, and MAG5) obtained from the MELMC accounts for more than 90% (Fig. 2). Two of them belonged to not-yet cultured (as axenic cultures) novel bacterial taxa (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Third generation sequencing technologies (e.g., PacBio-HiFi and Nanopore) and improved bioinformatics tools have allowed us to discover several novel microbial species, represented by MAGs, in different natural environments [74]. Unfortunately, many of these MAGs come from uncultivable microorganisms which cannot be systematically named following the rules of the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes [44]. Therefore, a roadmap for naming uncultivated microorganism has been proposed, in which genome sequences could serve as the type material for naming prokaryotic taxa [75]. Based on various genomic metrics (such as ANI and AAI), MAG5 represent a novel bacterial genus within the Paenibacillaceae family, for which the name Pristimantibacillus lignocellulolyticum is proposed here, following the rules of the SeqCode. In this case, the suffix bacillus is used to describe the morphology of the cells attached to lignocellulosic biomass, as found previously by scanning electron microscopy [13]. Moreover, MAG4 was classified as a novel species within the genus Ochrobactrum, which is a soil-dwelling bacterium [76]. Notably, the genus Ochrobactrum is possibly a later heterotypic synonym of the pathogen genus Brucella [47], but we maintain the designation for consistency with the named species closest to MAG4, and in accordance with Moreno et al. [77].

Interestingly, prophage sequences were found in the three high-quality MAGs retrieved from the MELMC. Among them, a complete viral sequence associated with the Salmonella phage 118970_sal3 was detected within MAG1 (Supplementary Table 1). We hypothesize that this phage could negatively impact the enterobacterial populations during the MELMC development, decreasing their abundance as was observed by Díaz-Garcia et al. [13]. However, the ecological relevance and the functional roles of bacteriophages within lignocellulolytic microbial communities are still unclear. Thus, further studies must explore the viral communities in these PBDC, as is reported for soils [78]. Moreover, the most abundant member of the MELMC (Ps. protegens; MAG1) was isolated as axenic culture. However, the other two members were not recovered as pure isolates by using commercial agar media (i.e., LB, R2A, and Cetrimide). Both O. gambitense and Pr. lignocellulolyticus could grow and maintain in a tripartite consortium, probably due to their metabolic interdependences between the MELMC species [79]. This MELMC could be an excellent system for further studies of culturomics, as is described for other microbial communities [80]. Nutritional requirements to design a suitable culture medium for isolation of O. gambitensis and Pr. lignocellulolyticum can be identified using the MAG4 and MAG5 sequence information. Moreover, a very low abundance (0.015%) MELMC member (B. subtilis) was isolated in an axenic culture (Fig. 2). We hypothesize that LB agar and incubation conditions favored the growth of this bacterium. Here, we suggested that B. subtilis could be present as a remnant species after the dilution-to-extinction process [13], being metabolically inactive within the MELMC, but it could be an excellent partner of Ps. protegens for the transformation of fossil-based plastics, as is reported by Roberts et al. [32].

Regarding lignocellulose transformation, Pr. lignocellulolyticus contains the biggest genomic capacity to deconstruct plant polysaccharides, in particular cellulose and xylan (Fig. 3), similar to what has been reported for Paenibacillus species [81]. On the other hand, Ps. protegens has the largest genomic potential to depolymerize lignin and catabolize its derived aromatic compounds (Supplementary Table 4) [82]. However, Pr. lignocellulolyticus could aid in the depolymerization process by producing laccases (from the AA1 family). Based on this evidence, we posit that both enzymatic synergism and division of labor are common features within the MELMC, similar to other PBDC [51, 68]. Following cheminformatic principles, which have been used in pharmacology and drug discovery [83], quantitative structural relationships (using SMILES and Tanimoto coefficients) between LDCC and PDCC were obtained (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 5). From these analyses, combined with target-specific functional annotation of MAGs, we propose that Ps. protegens could transform PBAT (a biodegradable fossil-based plastic). A predicted polyesterase [84] encoded in MAG1 could depolymerize PBAT to its units: adipic acid, 1,4-butanediol, and terephthalic acid; and then terephthalic acid could be incorporated into Ps. protegens metabolism. Based on the tripartite network (Fig. 5), cis-, cis-muconic acid, and benzoic acid were structurally similar to terephthalic acid. It is reported that cis-, cis-muconic acid can be chemically converted to terephthalic acid for the production of bio-PET from lignin [85]. Therefore, it could be anticipated that the catabolism of terephthalic acid (one of the building blocks of PET and PBAT) could be accomplished by the action of the muconate cycloisomerase (EC 5.5.1.1) or benzoate 1,2-dioxygenase (EC 1.14.12.10), which have catalytic activity on cis-, cis-muconic acid and benzoic acid, respectively [59, 86]. In fact, muconate cycloisomerase has been involved in the catabolism of aromatic intermediates obtained within the transformation of plastic additives [87]. Moreover, in Ps. putida KT2440 the gene benA encoding a benzoate 1,2-dioxygenase share a similarity of 35% with the gene tphA2 encoding a terephthalate 1,2-dioxygenase in Ps. umsogensis GO16 [88]. Uptake and catabolism of terephthalic acid has been described in other organisms, including different species of Pseudomonas, and proceeds via protocatechuate, a common intermedia in aerobic aromatic catabolism [89]. Notably, Ps. protegens (MAG1) contains the gene encoding a vanillate monooxygenase (EC 1.14.13.82), an enzyme involved in the catabolism of vanillate into protocatechuate [59]. This enzyme could have activity on monomethyl phthalate (a common plasticizer agent), who shares a structural similarity of nearly 70% with vanillate (Supplementary Table 5). To corroborate the structural similarities between LDCC and PDCC, additional molecular fingerprints would be helpful [90]. However, growth experiments can determine if Ps. protegens can catabolize some PDCC, and isotope-labeling experiments [91] could be also helpful to determine the depolymerization of PBAT and PU by this bacterium.

PHAs are versatile bio-based and biodegradable polymers that can be useful to replace fossil-based plastics [30]. As a significant finding in our study, we found that P. protegens (MAG1) harbors the pha cluster for the synthesis and accumulation of mcl-PHAs, like PHO (Fig. 6), a capability widespread in Pseudomonas species. Intracellular PHA can be hydrolyzed by the action of the PhaZ proteins, maintaining the turnover inside of the cells through synthesis and depolymerization cycles [92, 93]. In Ps. protegens a phaZ gene was found within the pha cluster. Moreover, PHA is released into the extracellular environment after the death of PHA-producing microorganisms. This polymer can be deconstructed into its units of 3-hydroxyalkanoic by the action of extracellular PHA depolymerases (e-PHA). Most of the e-PHA have specificity for PHB (short-chain length). However, some e-PHA, isolated from Bdellovibrio, Pseudomonas, or Streptomyces species, can act on mcl-PHA, such as PHO [94, 95]. In this study, we incubated the axenic culture (strain M5) of Ps. protegens with PHB or PHO nanoparticles as the sole carbon source, observing growth on both substrates. Despite the apparent absence of e-PHA within MAG1, it has been described that Pseudomonas species can degrade PHA using extracellular lipases, like those encoded in MAG1 (Supplementary Table 6). These findings suggest that P. protegens contains the genomic potential to synthesize mcl-PHAs and produces enzymes to depolymerize PHB and PHO; catabolizing its oligomers or monomers for growth (Fig. 6). Whether these oligo- and monomers could be re-polymerized into PHA, as suggested by some studies, still needs further and systematic investigation [96]. From a biotechnological perspective, PHA depolymerases are interesting due to their capacity to produce enantiopure R-hydroxycarboxylic with potential applications for the synthesis of antibiotics, and for conjugation of anti-cancer compounds [97].

In conclusion, the combined “top-down” enrichment strategy is an excellent approach to select a minimal and effective polymer-transforming microbial consortium. Here, the PacBio-HiFI metagenome sequencing was useful to reconstruct the genomes of the three most abundant MELMC species, unveiling two novel bacterial taxa involved in lignocellulose transformation. One of them (Pr. lignocellulolyticus) contains a wide genomic potential to deconstruct plant polysaccharides. Thus, this species can be a source of enzymes useful to improve the saccharification process in biorefineries. Moreover, the MELMC is dominated by Ps. protegens, which was able to isolate in axenic culture, displaying the highest genomic potential to (i) catabolize LDCC; (ii) depolymerize plastics, such as PBAT, PE, and PU; (iii) catabolize terephthalate and other PDCC, such as phthalates; and (iv) produce mcl-PHAs and degrade extracellular PHAs. As a key perspective, further studies can focus on the production of biodegradable plastics (i.e., PHAs), by Ps. protegens, using PDCC (e.g., terephthalic acid) and LDCC (Fig. 6), as it has been proposed for Ps. umsongensis and Ps. protegens strains [88, 98, 99].

Data availability

All data (raw and assemblies) are connected through the same BioProject ID, namely PRJNA842362.

References

Gielen D, Boshell F, Saygin D, Bazilian M, Wagner N, Gorini R. The role of renewable energy in the global energy transformation. Energ Strat Rev. 2019;24:38–50.

Ellis L, Rorrer N, Sullivan K, Otto M, McGeehan J, Román-Leshkov Y, et al. Chemical and biological catalysis for plastics recycling and upcycling. Nat Catal. 2021;4:539–56.

Singhvi M, Gokhale D. Lignocellulosic biomass: hurdles and challenges in its valorization. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;103:9305–20.

Liu Y, Nie Y, Lu X, Zhang X, He H, Pan F, et al. Cascade utilization of lignocellulosic biomass to high-value products. Green Chem. 2019;21:3499–535.

Chandel A, Garlapati V, Singh A, Antunes F, da Silva S. The path forward for lignocellulose biorefineries: Bottlenecks, solutions, and perspective on commercialization. Bioresour Technol. 2018;264:370–81.

Lopes A, Ferreira Filho E, Moreira L. An update on enzymatic cocktails for lignocellulose breakdown. J Appl Microbiol. 2018;125:632–45.

Wongwilaiwalin S, Laothanachareon T, Mhuantong W, Tangphatsornruang S, Eurwilaichitr L, Igarashi Y, et al. Comparative metagenomic analysis of microcosm structures and lignocellulolytic enzyme systems of symbiotic biomass-degrading consortia. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:8941–54.

Jiménez DJ, de Lima Brossi M, Schückel J, Kračun S, Willats W, van Elsas J. Characterization of three plant biomass-degrading microbial consortia by metagenomics- and metasecretomics-based approaches. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:10463–77.

Lazuka A, Auer L, O’Donohue M, Hernandez-Raquet G. Anaerobic lignocellulolytic microbial consortium derived from termite gut: enrichment, lignocellulose degradation and community dynamics. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:284.

Paixão D, Tomazetto G, Sodré V, Gonçalves T, Uchima C, Büchli F, et al. Microbial enrichment and meta-omics analysis identify CAZymes from mangrove sediments with unique properties. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2021;148:109820.

Liang Y, Ma A, Zhuang G. Construction of environmental synthetic microbial consortia: based on engineering and ecological principles. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:829717.

Jiménez DJ, Korenblum E, van Elsas JD. Novel multispecies microbial consortia involved in lignocellulose and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural bioconversion. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:2789–803.

Díaz-García L, Huang S, Spröer C, Sierra-Ramírez R, Bunk B, Overmann J, et al. Dilution-to-stimulation/extinction method: a combination enrichment strategy to develop a minimal and versatile lignocellulolytic bacterial consortium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2021;87:e02427–20.

Puentes-Téllez P, Falcao, Salles J. Construction of effective minimal active microbial consortia for lignocellulose degradation. Microb Ecol. 2018;76:419–29.

Jiménez DJ, Wang Y, Chaib de Mares M, Cortes-Tolalpa L, Mertens J, Hector RE, et al. Defining the eco-enzymological role of the fungal strain Coniochaeta sp. 2T2.1 in a tripartite lignocellulolytic microbial consortium. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2020;96:fiz186.

Jiménez DJ, Dini-Andreote F, van Elsas J. Metataxonomic profiling and prediction of functional behaviour of wheat straw degrading microbial consortia. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2014;7:92.

Jiménez DJ, Chaib De Mares M, Salles J. Temporal expression dynamics of plant biomass-degrading enzymes by a synthetic bacterial consortium growing on sugarcane bagasse. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:299.

Jiménez DJ, Maruthamuthu M, van Elsas JD. Metasecretome analysis of a lignocellulolytic microbial consortium grown on wheat straw, xylan and xylose. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2015;8:199.

Funnicelli M, Pinheiro D, Gomes-Pepe E, de Carvalho L, Campanharo J, Fernandes C, et al. Metagenome-assembled genome of a Chitinophaga sp. and its potential in plant biomass degradation, as well of affiliated Pandoraea and Labrys species. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;37:162.

Weiss B, Souza A, Constancio M, Alvarenga D, Pylro V, Alves L, et al. Unraveling a lignocellulose-decomposing bacterial consortium from soil associated with dry sugarcane straw by genomic-centered metagenomics. Microorganisms. 2021;9:995.

Cortes-Tolalpa L, Jiménez D, de Lima Brossi M, Salles J, van Elsas J. Different inocula produce distinctive microbial consortia with similar lignocellulose degradation capacity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:7713–25.

Carlos C, Fan H, Currie C. Substrate shift reveals roles for members of bacterial consortia in degradation of plant cell wall polymers. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:364.

Jiménez DJ, Dini-Andreote F, DeAngelis K, Singer S, Salles J, van Elsas J. Ecological insights into the dynamics of plant biomass-degrading microbial consortia. Trends Microbiol. 2017;25:788–96.

Kang D, Herschend J, Al-Soud W, Mortensen M, Gonzalo M, Jacquiod S, et al. Enrichment and characterization of an environmental microbial consortium displaying efficient keratinolytic activity. Bioresour Technol. 2018;270:303–10.

López-Mondéjar R, Algora C, Baldrian P. Lignocellulolytic systems of soil bacteria: a vast and diverse toolbox for biotechnological conversion processes. Biotechnol Adv. 2019;37:107374.

Moraes E, Alvarez T, Persinoti G, Tomazetto G, Brenelli L, Paixão D, et al. Lignolytic-consortium omics analyses reveal novel genomes and pathways involved in lignin modification and valorization. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:75.

Mendes I, Garcia M, Bitencourt A, Santana R, Lins P, Silveira R, et al. Bacterial diversity dynamics in microbial consortia selected for lignin utilization. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255083.

Bugg T, Ahmad M, Hardiman E, Rahmanpour R. ChemInform abstract: pathways for degradation of lignin in bacteria and fungi. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;43:1883–96.

Chen C, Dai L, Ma L, Guo R. Enzymatic degradation of plant biomass and synthetic polymers. Nat Rev Chem. 2020;4:114–26.

Jiménez DJ, Öztürk B, Wei R, Bugg T, Amaya Gomez C, Salcedo Galan F, et al. Merging plastics, microbes, and enzymes: highlights from an international workshop. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2022;88:e0072122. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.00721-22.

Auta H, Emenike C, Fauziah S. Screening of Bacillus strains isolated from mangrove ecosystems in Peninsular Malaysia for microplastic degradation. Environ Pollut. 2017;231:1552–9.

Roberts C, Edwards S, Vague M, León-Zayas R, Scheffer H, Chan G, et al. Environmental consortium containing Pseudomonas and Bacillus species synergistically degrades polyethylene terephthalate plastic. mSphere. 2020;5:e01151–20.

Kolmogorov M, Bickhart D, Behsaz B, Gurevich A, Rayko M, Shin S, et al. metaFlye: scalable long-read metagenome assembly using repeat graphs. Nat Methods. 2020;17:1103–10.

Parks D, Imelfort M, Skennerton C, Hugenholtz P, Tyson G. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015;25:1043–55.

Langmead B, Salzberg S. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–9.

Tanizawa Y, Fujisawa T, Nakamura Y. DFAST: a flexible prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline for faster genome publication. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:1037–9.

Bowers R, Kyrpides N, Stepanauskas R, Harmon-Smith M, Doud D, Reddy T, et al. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:725–31.

Grant JR, Stothard P. The CGView Server: a comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W181–4.

Bertelli C, Laird M, Williams K, Simon Fraser University Research Computing Group Lau B, Hoad G. et al. IslandViewer 4: expanded prediction of genomic islands for larger-scale datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W30–5.

Arndt D, Grant J, Marcu A, Sajed T, Pon A, Liang Y. et al. PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W16–21.

Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R, Oliver Glöckner F, Peplies J. JSpeciesWS: a web server for prokaryotic species circumscription based on pairwise genome comparison. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:929–31.

Rodriguez-R LM, Gunturu S, Harvey WT, Rosselló-Mora R, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. et al. The Microbial Genomes Atlas (MiGA) webserver: taxonomic and gene diversity analysis of Archaea and Bacteria at the whole genome level. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W282–8.

Rodriguez-R LM, Harvey WT, Rosselló-Mora R, Tiedje JM, Cole JR, Konstantinidis KT. Classifying prokaryotic genomes using the Microbial Genomes Atlas (MiGA) webserver. In: Trujillo ME, Dedysh S, DeVos P, Hedlund B, Kämpfer P, Rainey FA, et al. editors. Bergey’s manual of systematics of Archaea and Bacteria. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2015. p 1–11.

Konstantinidis KT, Rosselló-Móra R, Amann R. Uncultivated microbes in need of their own taxonomy. ISME J. 2017;11:2399–406.

Meier-Kolthoff J, Göker M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2182.

Meier-Kolthoff J, Auch A, Klenk H, Göker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:60.

Hördt A, López M, Meier-Kolthoff J, Schleuning M, Weinhold L, Tindall B, et al. Analysis of 1,000+ type-strain genomes substantially improves taxonomic classification of Alphaproteobacteria. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:468.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–9.

Zhang H, Yohe T, Huang L, Entwistle S, Wu P, Yang Z. et al. dbCAN2: a meta server for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W95–101.

Barter RL, Yu B. Superheat: an R package for creating beautiful and extendable heatmaps for visualizing complex data. J Comput Graph Stat. 2018;27:910–22.

Díaz-García L, Bugg TDH, Jiménez DJ. Exploring the lignin catabolism potential of soil-derived lignocellulolytic microbial consortia by a gene-centric metagenomic approach. Microb Ecol. 2020;80:885–96.

Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75.

Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases, and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D353–61.

Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2015;12:59–60.

Gan Z, Zhang H. PMBD: a comprehensive Plastics Microbial Biodegradation Database. Database (Oxford). 2019;2019:baz119.

Gambarini V, Pantos O, Kingsbury JM, Weaver L, Handley KM, Lear G. PlasticDB: a database of microorganisms and proteins linked to plastic biodegradation. Database (Oxford). 2022;2022:baac008.

Knoll M, Hamm T, Wagner F, Martinez V, Pleiss J. The PHA Depolymerase Engineering Database: a systematic analysis tool for the diverse family of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) depolymerases. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:89.

Fischer M, Pleiss J. The Lipase Engineering Database: a navigation and analysis tool for protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:319–21.

Brink DP, Ravi K, Lidén G, Gorwa-Grauslund MF. Mapping the diversity of microbial lignin catabolism: experiences from the eLignin database. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;103:3979–4002.

Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J, He S. et al. PubChem in 2021: new data content and improved web interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D1388–95.

Öztürk H, Ozkirimli E, Özgür A. A comparative study of SMILES-based compound similarity functions for drug-target interaction prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2016;17:128.

Landrum G. RDKit: Open-Source Cheminformatics Software. 2016.

Csardi G, Nepusz T. The Igraph Software Package for Complex Network Research. Compl Syst. 2006.

Pfennig N, Lippert KD. Über das Vitamin B12-Bedürfnis phototropher Schwefelbakterien. Archiv Mikrobiol. 1966;55:245–56.

Schirmer A, Jendrossek D. Molecular characterization of the extracellular poly(3-hydroxyoctanoic acid) [P(3HO)] depolymerase gene of Pseudomonas fluorescens GK13 and of its gene product. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7065–73.

Mhatre A, Kalscheur B, Mckeown H, Bhakta K, Sarnaik A, Flores A, et al. Consolidated bioprocessing of hemicellulose to fuels and chemicals through an engineered Bacillus subtilis-Escherichia coli consortium. Renew Energ. 2022;193:288–98.

Lin L. Bottom-up synthetic ecology study of microbial consortia to enhance lignocellulose bioconversion. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod. 2022;15:14.

Cortes-Tolalpa L, Salles J, van Elsas J. Bacterial synergism in lignocellulose biomass degradation – complementary roles of degraders as influenced by complexity of the carbon source. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1628.

Wang Y, Elzenga T, van Elsas JD. Effect of culture conditions on the performance of lignocellulose-degrading synthetic microbial consortia. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;105:7981–95.

Oh H, Park D, Seong H, Kim D, Sul W. Antarctic tundra soil metagenome as useful natural resources of cold-active lignocelluolytic enzymes. J Microbiol. 2019;57:865–73.

Reichart N, Bowers R, Woyke T, Hatzenpichler R. High potential for biomass-degrading enzymes revealed by hot spring metagenomics. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:668238.

Kang D, Huang Y, Nesme J, Herschend J, Jacquiod S, Kot W, et al. Metagenomic analysis of a keratin-degrading bacterial consortium provides insight into the keratinolytic mechanisms. Sci Total Environ. 2021;761:143281.

Peng X, Wilken S, Lankiewicz T, Gilmore S, Brown J, Henske J, et al. Genomic and functional analyses of fungal and bacterial consortia that enable lignocellulose breakdown in goat gut microbiomes. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6:499–511.

Nayfach S, Roux S, Seshadri R, Udwary D, Varghese N, Schulz F, et al. A genomic catalog of Earth’s microbiomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39:499–509.

Murray A, Freudenstein J, Gribaldo S, Hatzenpichler R, Hugenholtz P, Kämpfer P, et al. Roadmap for naming uncultivated Archaea and Bacteria. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:987–94.

Gohil K, Rajput V, Dharne M. Pan-genomics of Ochrobactrum species from clinical and environmental origins reveals distinct populations and possible links. Genomics. 2020;112:3003–12.

Moreno E, Blasco J, Letesson J, Gorvel J, Moriyón I. Pathogenicity and its implications in taxonomy: the Brucella and Ochrobactrum case. Pathogens. 2022;11:377.

Bi L, Yu D, Han L, Du S, Yuan C, He J, et al. Unravelling the ecological complexity of soil viromes: challenges and opportunities. Sci Total Environ. 2022;812:152217.

Zelezniak A, Andrejev S, Ponomarova O, Mende D, Bork P, Patil K. Metabolic dependencies drive species co-occurrence in diverse microbial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:6449–54.

Sood U, Kumar R, Hira P. Expanding culturomics from gut to extreme environmental settings. mSystems. 2021;6:e0084821.

Mathews S, Grunden A, Pawlak J. Degradation of lignocellulose and lignin by Paenibacillus glucanolyticus. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2016;110:79–86.

Nogales J, García JL, Díaz E. Degradation of aromatic compounds in Pseudomonas: a systems biology view. In: Rojo F, editor. Aerobic utilization of hydrocarbons, oils and lipids. Handbook of hydrocarbon and lipid microbiology. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 1–49.

Kunimoto R, Bajorath J. Design of a tripartite network for the prediction of drug targets. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2018;32:321–30.

Wallace P, Haernvall K, Ribitsch D, Zitzenbacher S, Schittmayer M, Steinkellner G, et al. PpEst is a novel PBAT degrading polyesterase identified by proteomic screening of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:2291–303.

Kohlstedt M, Weimer A, Weiland F, Stolzenberger J, Selzer M, Sanz M, et al. Biobased PET from lignin using an engineered cis, cis-muconate-producing Pseudomonas putida strain with superior robustness, energy and redox properties. Metab Eng. 2022;72:337–52.

Qi X, Yan W, Cao Z, Ding M, Yuan Y. Current advances in the biodegradation and bioconversion of polyethylene terephthalate. Microorganisms. 2022;10:39.

Medić A, Stojanović K, Izrael-Živković L, Beškoski V, Lončarević B, Kazazić S, et al. A comprehensive study of conditions of the biodegradation of a plastic additive 2,6-di-tert-butylphenol and proteomic changes in the degrader Pseudomonas aeruginosa san ai. RSC Adv. 2019;9:23696–710.

Narancic T, Salvador M, Hughes G, Beagan N, Abdulmutalib U, Kenny S, et al. Genome analysis of the metabolically versatile Pseudomonas umsongensis GO16: the genetic basis for PET monomer upcycling into polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microb Biotechnol. 2021;14:2463–80.

Werner A, Clare R, Mand T, Pardo I, Ramirez K, Haugen S, et al. Tandem chemical deconstruction and biological upcycling of poly(ethylene terephthalate) to β-ketoadipic acid by Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Metab Eng. 2021;67:250–61.

Rácz A, Bajusz D, Héberger K. Life beyond the Tanimoto coefficient: similarity measures for interaction fingerprints. J Cheminform. 2018;10:48.

Tian L, Ma Y, Ji R. Quantification of polystyrene plastics degradation using 14C isotope tracer technique. Methods Enzymol. 2021;648:121–36.

Prieto A, Escapa I, Martínez V, Dinjaski N, Herencias C, de la Peña F, et al. A holistic view of polyhydroxyalkanoate metabolism in Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:341–57.

Tarazona N, Hernández‐Arriaga A, Kniewel R, Prieto M. Phasin interactome reveals the interplay of PhaF with the polyhydroxyalkanoate transcriptional regulatory protein PhaD in Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol. 2020;22:3922–36.

Tarazona NA, Machatschek R, Lendlein A. Influence of depolymerases and lipases on the degradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates determined in langmuir degradation studies. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2020;7:2000872.

Viljakainen V, Hug L. The phylogenetic and global distribution of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoate bioplastic‐degrading genes. Environ Microbiol. 2021;23:1717–31.

Myung J, Strong N, Galega W, Sundstrom E, Flanagan J, Woo S, et al. Disassembly and reassembly of polyhydroxyalkanoates: recycling through abiotic depolymerization and biotic repolymerization. Bioresour Technol. 2014;170:167–74.

O’Connor S, Szwej E, Nikodinovic-Runic J, O’Connor A, Byrne A, Devocelle M, et al. The anti-cancer activity of a cationic anti-microbial peptide derived from monomers of polyhydroxyalkanoate. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2710–8.

Tiso T, Narancic T, Wei R, Pollet E, Beagan N, Schröder K, et al. Towards bio-upcycling of polyethylene terephthalate. Metab Eng. 2021;66:167–78.

Ramírez-Morales JE, Czichowski P, Besirlioglu V, Regestein L, Rabaey K, Blank LM, et al. Lignin aromatics to PHA polymers: nitrogen and oxygen are the key factors for Pseudomonas. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2021;9:10579–90.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicole Heyer (from DSMZ Institute) for excellent technical assistance regarding metagenomics library preparation and sequencing; Sixing Huang (from DSMZ Institute) for bioinformatics assistance; Juan F. Saldarriaga (from Universidad de los Andes) for providing the resources and infrastructure to carry out the PHA experiments; and Dr Lorena Castro (from Agrosavia) for providing the PHO material. In addition, we thank the Faculty of Sciences at the Universidad de los Andes for providing administrative support. This work was supported by the FAPA project (number PR.3.2018.5287) obtained by Diego Javier Jiménez at the Universidad de los Andes. All authors acknowledge financial provided by the Vice Presidency for Research and Creation publication fund at the Universidad de los Andes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions following the CRediT taxonomy (https://casrai.org/credit/) are as follows: conceptualization: CADR, LD-G, DJJ; data curation: CADR, LD-G, CS, BB; formal analysis: CADR, LD-G, NAT, LMR-R, DJJ; funding acquisition: JO, DJJ; investigation: CADR, LD-G, KH, CS, LMR-R, BB, DJJ; methodology: CADR, LD-G, NT, DJJ; project administration: DJJ; resources: KH, CS, BB, JO, DJJ; software: CDAG, LD-G, LMR-R, BB; supervision: DJJ; validation: DJJ; visualization: CADR, LD-G, LMR-R, DJJ; writing—original draft: CADR, DJJ; writing—review and editing: LD-G, NT, CS, LMR-R, BB, JO, DJJ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Díaz Rodríguez, C.A., Díaz-García, L., Bunk, B. et al. Novel bacterial taxa in a minimal lignocellulolytic consortium and their potential for lignin and plastics transformation. ISME COMMUN. 2, 89 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43705-022-00176-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43705-022-00176-7

This article is cited by

-

Potential routes of plastics biotransformation involving novel plastizymes revealed by global multi-omic analysis of plastic associated microbes

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Polyurethane-Degrading Potential of Alkaline Groundwater Bacteria

Microbial Ecology (2024)

-

Enhanced bioconversion of grass straw into bioethanol by a novel consortium of lignocellulolytic bacteria aided by combined alkaline-acid pretreatment

Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery (2024)