Abstract

Ophiolites occur widely in orogenic belts, yet their origins remain controversial. Here we present a modern example with a geodynamic model from Timor, eastern Indonesia, where Earth’s youngest supra-subduction zone (SSZ)-type ophiolitic fragments are exposed. Zircon U-Pb ages and geochemical data indicate a short timespan (~10 to 8 Ma) for the magmatic sequence with boninitic and tholeiitic arc compositions. We interpret the Timor ophiolite as part of the infant Banda arc-forearc complex, which formed with the opening of the North Banda Sea and subsequent arc-continent collision along the irregular Australian continental margin. Our study connects the occurrence of small, short-lived ocean basins in the western Pacific with orogens around the globe where ephemeral SSZ-type ophiolites occur. These orogenic ophiolites do not represent preexisting oceanic crust, but result from upper-plate processes in early orogenesis and thus mark the onset of collision zone magmatism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

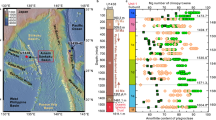

Ophiolites are segments of oceanic crust and underlying uppermost mantle that outcrop in orogenic belts that follow continental margins. Most ophiolites display island arc geochemical features suggestive of sea-floor spreading related to subduction zone processes. These are referred to as supra-subduction zone (SSZ) ophiolites1. SSZ-type ophiolites may form during the initial stage of subduction1,2, and yield a magmatic rock association similar to that of the Eocene Izu-Bonin-Mariana (IBM) forearc3,4,5. The IBM forearc however, does not conform to the short time period (<20 or even <10 myr) between formation and emplacement typical of most SSZ-type ophiolites2,3,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Modern SSZ-type ophiolites offer alternative examples that can be investigated to understand their origins. The Timor ophiolite in the Banda forearc, eastern Indonesia (Fig. 1), provides such an example. This ophiolite is situated in an active arc-continent collision setting that has persisted since the Late Miocene14,15.

a Simplified topographic map of eastern Indonesia, SE Asia. Thick black lines denote plate boundaries. b Map of the Banda Sea region showing sample localities, main tectonic units, active volcanoes, and main thrust faults. The arrow shows the plate motion vector. c Simplified geologic map of Timor and Moa islands (modified after16,29).

The Timor ophiolite forms a belt that stretches from Timor to Moa Island between the active Banda magmatic arc and approaching Australian continent (Fig. 1). Common ophiolitic components are observed, including basalt, dolerite, gabbro, and ultramafic rocks, with intrusive granitic plugs that penetrate all rock types. However, sheeted dikes are not present14,16. This ophiolitic suite displays a “top to the north” sense of motion and is separated from the underlying metamorphic massif by a series of N-dipping low-angle normal faults in northern Timor17. Ductile thrusting has been suggested along the boundary between the metamorphic massifs and the underlying Australian Sequence17. It is uncertain whether there is a metamorphic sole present. The Mutis metamorphic complex, which underlies the peridotite, has been proposed as a possible metamorphic sole18), however some researchers have argued that it is too thick (>1 km) to be interpreted as a metamorphic sole16. The magmatic suite is composed mainly of arc tholeiitic basalt and high-Mg andesite, thus being regarded generally as a product of island arc and forearc magmatism14,16. This is consistent with the occurrence of the Ocussi pillow basalts, which are believed to represent the remains of submarine volcanic edifices14. K-Ar ages of pillow basalts and dolerite dikes from these volcanics range from 6–2 Ma19, with Ar-Ar ages of ~6 Ma14. Since these volcanic rocks are unconformably overlain by Late Miocene (~7–6 Ma) forearc sedimentary rocks20,21, the above dates are thought to have experienced open-system isotopic exchange and thus a minimum formation age of ~6 Ma has been assumed14.

This Late Miocene age assumption and the arc-forearc magma association have led workers to relate the generation of the Timor ophiolite to a post-collisional lithospheric extension14 or coherent opening of the Banda Sea20,21. The Banda Sea (Fig. 1b) consists essentially of three extensional basins that opened stepwise from the North Banda Basin (12–7 Ma) to the South Banda Basin (6.5–3 Ma) and the Weber Trough (<3 Ma)22,23. Such a sequential opening was attributed to southward trench retreat and associated rollback of the subducted Indo-Australian oceanic lithosphere (or the Banda Embayment), with resultant upper-plate extension since ~15 Ma after the Sula Spur started colliding with Sundaland24. The extension split both the Sula Spur crust24 and Sundaland25. The split Sundaland forearc fragments are widely distributed around the Banda Sea region as well as in Timor (Fig. 1c), as the so-called Banda Terrane21 or Banda Allochthon25. Slab rollback also led to the formation of the Banda arc in north Timor, which started to exhibit magmatic activity around ~8 Ma22,26. The arc magmatism around the Alor-Wetar segment ceased from ~3 Ma26 (Fig. 1b), owing to collisional push from the advancing Australian continent27,28. This arc-continent collision resulted in southward emplacement of magmatic and underlying ultramafic rocks in the forearc region to form the ophiolite on Timor and Moa17,29.

We report zircon U-Pb age and whole-rock geochemical data from magmatic rocks of the Timor ophiolite. These include 10-Ma boninites from Moa and 8-Ma tholeiitic arc rocks from Timor. Our results suggest that these rocks formed in a near-trench spreading environment during subduction re-initiation and rapidly emplaced onto the Australian continent due to diachronous collisions between Sundaland and the incoming Australian plate. Based on the scenario in Timor, we propose that SSZ-type ophiolites found in orogens worldwide should be classified as “orogenic ophiolites” as they result from upper-plate processes during the beginning stage of accretionary or collisional orogenies.

Results and discussion

Zircon U-Pb ages

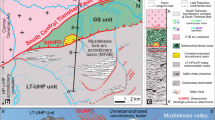

Twelve samples of dolerite, gabbro, and plagiogranite from Timor and Moa Island were dated using zircon U-Pb geochronology (Fig. 2a; see Supplementary Fig. S1 and Data S1 for details). Six dolerite and gabbro samples from Ocussi, Timor, that were collected along a continuous roadcut section (Fig. 2b) gave a narrow weighted 206Pb/238U mean age range from ~8.7 to 8.1 Ma (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S1). Two plagiogranite samples from west Atapupu, Timor (Fig. 2c) gave identical ages of ~8.7 Ma, while two spilite samples from east Atapupu (Fig. 2c) gave slightly older ages of 10.2 ± 0.1 and 10.1 ± 0.2 Ma (Fig. 2a). Further east, a gabbro and a plagiogranite from western Moa Island (Fig. 1c) yielded overlapping ages at 10.1 ± 0.1 Ma and 10.3 ± 0.1 Ma, respectively (Fig. 2d). These zircon U-Pb isotopic results define two age clusters that show that the entire magmatic suite formed within a short period, from ~10 to 8 Ma (Fig. 2a).

a Colored horizontal bands represent 206Pb/238U ages with ±2σ uncertainties of each zircon date. Vertical black lines indicate the weighted mean 206Pb/238U ages of each sample; with dark grey boxes showing ±2σ uncertainties calculated from mean square weighted deviation (MSWD) and light grey boxes showing the propagated ±2% errors for LA-ICPMS. Samples are plotted bottom to top according to the spatial distribution from east to west. A density plot of the age distribution of all samples is given in the lower part. b, c, d Geologic sketch maps with sample localities of Ocussi, Atapupu and West Moa areas, with dated samples underlined (West Moa map is modified from Kaneko et al.17). The legends in (b) are simplified rock successions of the Timor ophiolite. The ophiolite rocks and overlying units are probably fault-bounded16.

Whole-rock geochemistry

All samples analyzed, except the two spilites, were relatively well-preserved (LOI < 4 wt%; Supplementary Data S2) with representative lava compositions. As the spilites have extremely high Na2O contents (8.1 and 11.5 wt%) with a highly chloritized groundmass (Supplementary Fig. S2), they were excluded from detailed petrogenetic analysis. Our geochemical data indicate that all basic samples (dolerite and gabbro) from Moa are boninitic3,30, in contrast to samples from Timor that plot in the medium-Fe field, typical of island arc tholeiites (Fig. 3a). This result is consistent with our earlier work16, which reported high-Mg andesites with compositions ranging from low-Si to high-Si boninites3,30. The Moa boninitic samples have the highest MgO and the lowest TiO2, relative to the Atapupu gabbro samples (with intermediate values) and the Atapupu basalts/dolerites and Ocussi tholeiitic samples that have the lowest MgO and highest TiO2 (Fig. 3b).

a Plot of FeO* versus MgO that divides the BADR series into tholeiitic (TH; high-Fe and medium-Fe) and calc-alkaline (CA; low-Fe). Boninitic samples are also plotted for comparison. Medium-Fe rocks are typical of island arc tholeiites3. b Plot of TiO2 versus MgO with tectonic discrimination boundaries (See Supplementary Figs. S3–S5 for details). Large symbols are from this study, and small symbols are from literature data (Supplementary Data S3).

The tholeiitic and boninitic samples differ markedly in their REE and incompatible element patterns (Fig. 4). The dated Ocussi dolerites and gabbros (SiO2 = 50.8–54.8 wt%) show flat REE patterns (Fig. 4a), almost identical to those of the undated basalts from Ocussi (SiO2 = 54.4–55.1 wt%) and Atapupu (SiO2 = 52.1–53.5 wt%). Their REE abundances are about ten times above chondritic values (Fig. 4a, b). The Atapupu dolerite and gabbro (SiO2 = 52.8–55.7 wt%; no age data because of rare zircon separates) possess lower REE concentrations compared to the samples described above, with some displaying subtle La enrichment relative to Ce (Fig. 4b). The Atapupu spilites and plagiogranites both show negative Eu anomalies, indicative of plagioclase crystallization. All samples from Moa, including gabbros, dolerites, and plagiogranites, display spoon-shaped REE patterns subparallel to each other with lower LREE abundance (Fig. 4c) analogous to boninitic rocks from the Troodos ophiolite31. Among the Moa samples, REE concentrations are seen to increase with elevated SiO2, indicative of fractional crystallization. The incompatible element patterns of all basic samples show LILE enrichment (Ba, Th, U, Pb, and Sr) compared to HFSE (Nb, Ta, Zr, and Hf) (Fig. 4d–f), which is consistent with a subduction-related origin. Detailed geochemical and isotopic characterization is beyond the scope of this paper and will be given in a separate article under preparation.

Earth’s youngest SSZ-type ophiolite and its magma generation

Our zircon age data obtained from dolerites, gabbros, spilites and plagiogranites (Fig. 2), attest to their very brief magmatic histories (~10–8 Ma). This age range estimate is also consistent with the stratigraphy of the ophiolite sequence, seen in the field to underly Late Miocene (~7–6 Ma) sedimentary rocks20. No magmatic zircons were available for U-Pb dating from Timor basalts, and we argue that these basalts are cogenetic with other magmatic rocks in Timor, given their similarities in bulk rock geochemical compositions (Figs. 3 and 4). The magmatism appears to have started at ~10 Ma with a boninitic composition, forming the rocks exposed on Moa Island. It ended at ~8 Ma with the tholeiitic arc rocks that crop out in Atapupu and Ocussi (Fig. 2). The magmatic progression observed in this region differs from the one proposed for the IBM forearc crust, where forearc basalts are thought to have formed before boninites32. However, the Timor magmatic progression may be akin to those observed in the Troodos ophiolite, where boninites and tholeiitic basalts are interbedded31. The supra-subduction zone magmatic rocks discussed here were soon transported to their present locations by arc-continent collision around the Timor region. This process began as early as ~9.8 Ma and no later than ~5.5 Ma15,28, and gave birth to the youngest known SSZ-type ophiolitic complex on Earth33. Note that a magmatic duration of ~10–8 Ma is broadly coeval with, but slightly shorter than, the opening of the North Banda Sea (~12–7 Ma) and coincides with, or just predates the initiation of Banda arc magmatism (~8 Ma).

To examine the genetic relation between the Timor ophiolite and associated magmatism in and around the Banda Sea region, we utilize a MgO-TiO2 plot for basic rocks to discriminate their tectonic setting (Fig. 3b and see Supplementary Methods and Figs. S3–S5 for details). The 8-Ma tholeiitic rocks from Ocussi and Atapupu plot closely to the Banda arc volcanics (<8 Ma). But in general, the former has higher MgO contents than the latter, which argues for an infant intra-oceanic arc or proto-Banda arc origin. In comparison, coeval rocks from the North Banda Sea with higher TiO2 contents plot in the incipient spreading region, indicating less water involved in their mantle source5. The 10-Ma boninitic rocks from Moa plot in the forearc region. Notably, these rocks, along with the Troodos boninites, exhibit significant Nb-Ta enrichment relative to La in their incompatible element patterns (Fig. 4f). This is interpreted to result from dehydration of subducted pelagic sediments in the absence of rutile34. Therefore, the Moa boninitic rocks likely resulted from the melting of a refractory and hydrated mantle source. Since these boninitic rocks are the first melt of the Timor ophiolite, we infer a preexisting depleted mantle wedge as the mantle source.

The presence of a depleted mantle wedge in the region could be attributed to prior subduction events. Considering the Banda Sea opening since the Miocene, it is likely that the leading edge of the Banda Embayment was subducted beneath the Sundaland margin or, more precisely, a confined ocean basin during the Oligocene. This may have resulted in the formation of the Dai tholeiitic arc rocks approximately 32–25 Ma35. The present forearc position of Dai Island and the forearc fragments of Sundaland in Mutis, Timor (Fig. 1) suggest that these rocks, along with the depleted mantle wedge, may have split from upper-plate during the Banda Sea opening to reach their current location25. Therefore, the 10-Ma boninitic rocks in Moa likely formed due to re-melting of a preexisting depleted hydrous harzburgite (mantle wedge) during the extension of the Sundaland forearc lithosphere. In this case, heterogeneous drifted forearc fragments could include lherzolites that had undergone less depletion than the mantle beneath Moa. Combined with the presence of lherzolites at Mutis, Atapupu, and Dili, Timor16, the 8-Ma infant intra-oceanic arc around Atapupu and Ocussi, Timor could be attributed to the melting of less depleted lherzolite during progressive subduction stages.

Moa boninitic and Timor tholeiitic magmatism during 10–8 Ma shifted northward since 8 Ma to form the Banda arc26. Since the collision between the Australian continent and the Banda arc around the Aileu, Timor region occurred during ~9.8 to 5.5 Ma28, it is likely that the arrival of buoyant subducted crust at the infant arc or “proto-arc” caused the flattening of the subduction dip, leading to a northward shift of the arc segment27,28. Therefore, it is suggested that crustal rocks of the Timor ophiolite were formed in the near-trench or forearc setting relative to the present-day Banda arc, and were emplaced onto the Australian continental margin within 5 million years of its formation.

A propagating collision-driven model for the Timor ophiolite

Considering the regional tectonic framework that is characterized by an irregular margin of a northward-colliding Australian continent (Fig. 1a), with initial contact at ~23 Ma between the incoming Sula Spur promontory and the Sundaland margin24, we propose a propagating collision-driven model in four successive stages (Fig. 5) as representative of the formation and rapid emplacement of the Timor ophiolite:

-

(1)

At ~15 Ma (Fig. 5a): Post-collisional extensions started in the region, giving rise to early stage of fragmentation in the Sula Spur, as the consequence of subduction hinge retreat into the Banda Embayment and accompanying slab rollback24. Although the slab rollback may have been affiliated with a change in a transform fault east of Sumba to a west-dipping subduction36, we argue instead for a preexisting Oligocene intra-oceanic subduction that formed the Dai arc rocks35. This Oligocene subduction halted because of the Sula Spur collision, and thus the ocean basin became trapped and partially accreted to form the East Sulawesi ophiolite37.

-

(2)

At ~8 Ma (Fig. 5b): The trench retreat and slab rollback caused not only the opening of the North Banda Basin (~12–7 Ma) but also the reactivation of the halted subduction to account for the Banda magmatic arc system. Regional extension propagated southward, resulting in the splitting of the Banda Allochthon into fragments off the Sundaland margin25, including the Sumba microcontinent, the Mutis metamorphic complex, Dai arc rocks, and associated mantle rocks. Meanwhile, subduction zone magmatism began at ~10 Ma with boninitic rocks forming in the near-trench or forearc setting due to an elevated geotherm related to sea-floor spreading that preferentially melted a preexisting refractory and hydrated mantle wedge. Later, this infant Banda arc evolved into its main magmatic stage, forming tholeiitic arc rocks during ~8.7 to 8.1 Ma.

-

(3)

At ~3 Ma (Fig. 5c): Successive trench retreat and slab rollback induced the regional collision between Timor and indenter promontory of the approaching Australian continental margin at about 9.8–5.5 Ma28. This collision may have caused a northward shift of the arc segment (~8 Ma) and ushered a new phase of seafloor spreading that opened the South Banda Basin (~6.5–3 Ma). This spreading may have involved intra-arc rifting, leaving the remnant arc complex preserved as the Banda Ridge in the north, while the main Banda magmatic arc continued to develop in the south23. Progressive accretion of the Timor-Moa infant arc complex onto the Australian margin is responsible for its rapid or even “near-coeval” emplacement of the ophiolite. This arc-continent collision, in turn, terminated the arc magmatism around the Alor-Wetar segment before ~3 Ma. However, subduction and arc magmatism are still occurring on the eastern side of Alor-Wetar26.

-

(4)

At Present (Fig. 5d): Along with the most recent stage of rifting that formed the Weber Deep in front of the Banda volcanic arc in the east, upper-plate extension propagated westward in the Sunda backarc. This initiated Flores Basin extension and Quaternary basaltic volcanism in southern Sulawesi38,39. This extension is happening because the Sunda slab, which has penetrated into the lower mantle40, is retreating north of the Argo Abyssal Plain, similar to what happened with the Banda slab in the east. Australia advancing on the forearc side has caused a new phase of arc-continent collision around Sumba21, and replicated the scenario at Timor. Magmatic activity along the eastern Sunda arc can be expected to cease soon after southward accretion of its arc-forearc forms an enlarged Sumba island.

A Timor perspective on SSZ-type orogenic ophiolites

The Timor example illustrates a modern scenario of slab rollback and near-trench spreading in association with diachronous arc-continent collision, controlled by an irregular continental margin41,42. The inherited structure of the Australian plate and limited space for the subducting embayment thereby caused the infant arc to collide soon with the approaching Australian plate. According to thermo-mechanical modeling results42, the lifespan of ophiolites formed in this manner is mainly constrained by the duration of near-trench spreading and stress transfer, less than 20 million years in general or even shorter as in Timor. This offers a mechanism that not only terminates the nascent arc-forearc magmatism but also produces an “infant arc-forearc” type ophiolite with an ephemeral lifespan. Under such a tectonic framework, these SSZ-type ophiolites that consist of near-coeval sequences are generated by upper-plate processes at the initial stage of orogenesis and thus can mark the onset of collision zone magmatism.

SSZ-type ophiolites with brief magmatic records are present in orogens worldwide, such as the Bay of Islands ophiolite within the Appalachian7,43, the Coastal Range ophiolite from western USA10,44, and those exposed widely along the elongated Tethyan belt3,8,9,12,45 and SW Pacific margin10,44. According to the Timor scenario, we propose to refer to these as “orogenic ophiolites” because they result from upper-plate processes during accretionary or collisional orogenies. Our Timor study, furthermore, provides new insight into the presence of inherited mantle rocks in SSZ-type orogenic ophiolites. The inherited mantle may have recorded the petrogentic processes in earlier subduction events, thus contributing to the geochemical heterogeneities in the magmatic crustal unit. This finding aligns with the notable observations from certain Tethyan ophiolites along the eastern Mediterranean region31,46. Many of them contain crustal units exhibiting diverse geochemical signatures, generally varying from MORB-like to island-arc tholeiites and boninites similar to the IBM forearc crust32. These Tethyan ophiolites, however, are also characterized by short lifespans of magmatic histories that require a specific tectonic setting we argue to resemble the Timor scenario.

Our Timor model for the orogenic ophiolites agrees well with the occurrence of small, short-lived ocean basins in the western Pacific on modern Earth. This process is seen to be cyclical in the Cenozoic generation of SSZ-type ophiolites by recurrent intra-oceanic arcs along the NE Australia-Pacific margin10. Another example is the magma system in the Mathew and Hunter subduction zone generated by a collision between the Vanuatu Arc and Loyalty Ridge. This pre-arc, near-trench magma system is believed to have formed in a sinistral strike-slip system where arc-parallel extension is expected to eventually lead to the protolith complex of a future ophiolite47. The presence of coeval backarc spreading there47 also suggests analogues with the formation of the North Banda Sea. SSZ-type ophiolites have been documented north of Banda, in regions circumnavigating marginal Southeast Asian basins, including Zambales, Luzon ~45 Ma48, Palawan and Mindoro ~35 Ma49,50, and Eastern Taiwan 17–14 Ma51,52. Their lifespans, from magmatic formation to emplacement, was no longer than 20 million years, which is consistent with the thermo-mechanical modelling results42. In addition, the formation of these ophiolites were related to previous collisions48,53, as observed in Timor and along the NE Australia-Pacific margin10,47. Nonetheless, each ophiolite is expected to have a unique origin related to its specific geologic setting and geometry. How to correlate these orogenic ophiolites with regional plate reconstruction40,54 is critical to enhance our understanding of not only the birth and demise of marginal basins in the region, but also the cyclic and interactive subduction/accretion/collision processes that operated throughout the global orogeny.

Methods

Zircon U-Pb geochronology

Cathodoluminescence (CL) images of zircons were taken at the Institute of Earth Sciences of Academia Sinica, Taiwan, to examine the internal structure of individual zircon grains and to select positions for laser analysis. In situ zircon U-Pb dating was performed with an Agilent 7900 Q-ICP-MS coupled to a Photon Machines Analyte G2 excimer laser ablation system at the same institute following the analytical procedures in Chiu et al.55. The spot size was ~35 μm. Zircon standard GJ-1 was used to perform calibration, and two other zircon standards 91500 and Plešovice were used for data quality control. Data of U‐Th‐Pb isotopic ratios were processed using GLITTER software version 4.456. Common lead was corrected following Andersen57. Calculation and plots for weighted mean U‐Pb dates and concordia diagrams were performed by Isoplot v. 4.1558. Weighted mean dates are given with 2σ internal and external uncertainties; the former was calculated from the mean square weighted deviation (MSWD), and the latter was calculated with a propagated external uncertainty of 2% to account for the long-term reproducibility of standards59. All studied samples rarely contain inherited zircons (Supplementary Data S1).

Whole-rock major and trace elements analyses

For whole-rock geochemical analyses, fresh-looking parts of rock samples were carefully cut and then crushed by a jaw crusher. After hand‐picking to remove unfresh portions, rock chips were pulverized by an agate mill and FRITCH Planetary Ball Mill Puluerisette 5. The resulting rock powders were fused using anhydrous lithium tetraborate (Li2B4O7) as a flux (10 times the mass of the samples) to make glass beads. Major element oxides of the glass beads were measured by a Rigaku® RIX 2000 XRF spectrometer at the Department of Geosciences, National Taiwan University. Loss‐on‐ignition was obtained after heating at 900 °C for 4 h. Trace elements were analyzed by the dissolution of the fused glass beads using an Agilent 7500cx Q-ICP-MS at the Institute of Earth Sciences of Academia Sinica. Samples were first dissolved in Teflon beakers using a HF‐HNO3 (1:1) mixture for more than 2 h at ~100 °C. The solutions were evaporated to dryness, refluxed with 7 N HNO3 and dried again, and finally dissolved in 2% HNO3 with an addition of 10 ppb Rh and Bi as the internal standards. The final sample/solution weight ratio is 1:1500. The relative standard deviation is generally better than 5% for most trace elements, as shown by the statistics on duplicate analyses of the USGS standards (AGV‐2, BCR‐2, BHVO‐2, and DNC‐1; Supplementary Data S4). Detailed analytical procedures can be found in Lin et al.60. To more precisely calibrate certain key trace elements with extremely low concentrations, e.g., Nb, La, and Ta, the dilution factors of the standards were adjusted, from x1500 to x150000, to construct calibration curves best approximating the concentration ranges of the samples. We note that the key element concentrations obtained using the routine procedure and the adjusted calibration curves are generally consistent or even identical within 2σ.

Data availability

The dataset used in this study are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23641545.

References

Pearce, J. A., Lippard, S. & Roberts, S. Characteristics and tectonic significance of supra-subduction zone ophiolites. Geol. Soc. London, Special Publ. 16, 77–94 (1984).

Shervais, J. W. Birth, death, and resurrection: the life cycle of suprasubduction zone ophiolites. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2, 1010 (2001).

Pearce, J. A. & Robinson, P. The Troodos ophiolitic complex probably formed in a subduction initiation, slab edge setting. Gondwana Res. 18, 60–81 (2010).

Stern, R. J., Reagan, M., Ishizuka, O., Ohara, Y. & Whattam, S. To understand subduction initiation, study forearc crust: To understand forearc crust, study ophiolites. Lithosphere 4, 469–483 (2012).

MacLeod, C. J., Johan Lissenberg, C. & Bibby, L. E. “Moist MORB” axial magmatism in the Oman ophiolite: the evidence against a mid-ocean ridge origin. Geology 41, 459–462 (2013).

Searle, M. & Stevens, R. Obduction processes in ancient, modern and future ophiolites. Geolog. Soc. London, Special Publ. 13, 303–319 (1984).

Cawood, P. A. & Suhr, G. Generation and obduction of ophiolites: constraints from the Bay of Islands Complex, western Newfoundland. Tectonics 11, 884–897 (1992).

Hacker, B. R. Rapid emplacement of young oceanic lithosphere: argon geochronology of the Oman ophiolite. Science 265, 1563–1565 (1994).

Dilek, Y., Furnes, H. & Shallo, M. Suprasubduction zone ophiolite formation along the periphery of Mesozoic Gondwana. Gondwana Res. 11, 453–475 (2007).

Whattam, S. A., Malpas, J., Ali, J. R., Smith, I. E. & New, S. W. Pacific tectonic model: cyclical intraoceanic magmatic arc construction and near‐coeval emplacement along the Australia‐Pacific margin in the Cenozoic. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 9, Q03021 (2008).

Dilek, Y. & Furnes, H. Ophiolite genesis and global tectonics: geochemical and tectonic fingerprinting of ancient oceanic lithosphere. GSA Bulletin 123, 387–411 (2011).

Dai, J. et al. Rapid forearc spreading between 130 and 120 Ma: evidence from geochronology and geochemistry of the Xigaze ophiolite, southern Tibet. Lithos 172, 1–16 (2013).

Rutte, D., Garber, J., Kylander‐Clark, A. & Renne, P. R. An exhumation pulse from the nascent Franciscan subduction zone (California, USA). Tectonics 39, e2020TC006305 (2020).

Harris, R. Peri-collisional extension and the formation of Oman-type ophiolites in the Banda Arc and Brooks Range. Geolog. Soc. London, Special Publ. 60, 301–325 (1992).

Berry, R., Thompson, J., Meffre, S. & Goemann, K. U–Th–Pb monazite dating and the timing of arc–continent collision in East Timor. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 63, 367–377 (2016).

Ishikawa, A., Kaneko, Y., Kadarusman, A. & Ota, T. Multiple generations of forearc mafic–ultramafic rocks in the Timor–Tanimbar ophiolite, eastern Indonesia. Gondwana Res. 11, 200–217 (2007).

Kaneko, Y. et al. On-going orogeny in the outer-arc of the Timor–Tanimbar region, eastern Indonesia. Gondwana Res. 11, 218–233 (2007).

Sopaheluwakan, J., Helmers, H., Tjorkrosapoetro, S. & Nila, E. S. Medium pressure metamorphism with inverted thermal gradient associated with ophiolite nappe emplacement in Timor. Neth. J. Sea Res. 24, 333–343 (1989).

Abbott M., Chamalaun F. Geochronology of some Banda Arc volcanics. In: Barber A. J., Wiryosujono S. (eds). The Geology and Tectonics of Eastern Indonesia, vol. 2. Geological Research and Development Centre, Special Publications: Bandung, Indonesia, 1981, 253–268.

Carter, D. J., Audley-Charles, M. G. & Barber, A. Stratigraphical analysis of island arc—continental margin collision in eastern Indonesia. J. Geolog. Soc. 132, 179–198 (1976).

Harris R. The nature of the Banda Arc–continent collision in the Timor region. Arc-continent collision. Springer, 2011, pp 163–211.

Honthaas, C. et al. A Neogene back-arc origin for the Banda Sea basins: geochemical and geochronological constraints from the Banda ridges (East Indonesia). Tectonophysics 298, 297–317 (1998).

Hinschberger, F. et al. Late Cenozoic geodynamic evolution of eastern Indonesia. Tectonophysics 404, 91–118 (2005).

Spakman, W. & Hall, R. Surface deformation and slab–mantle interaction during Banda arc subduction rollback. Nat. Geosci. 3, 562–566 (2010).

Zimmermann, S. & Hall, R. Provenance of Cretaceous sandstones in the Banda Arc and their tectonic significance. Gondwana Res. 67, 1–20 (2019).

Elburg, M., Foden, J., Van Bergen, M. & Zulkarnain, I. Australia and Indonesia in collision: geochemical sources of magmatism. J. Volcanol. Geothermal Res. 140, 25–47 (2005).

McCaffrey, R. Seismological constraints and speculations on Banda Arc tectonics. Neth. J. Sea Res. 24, 141–152 (1989).

Keep, M. & Haig, D. W. Deformation and exhumation in Timor: distinct stages of a young orogeny. Tectonophysics 483, 93–111 (2010).

Harris R., Long T. The Timor ophiolite, Indonesia: model or myth? In: Dilek Y., Moores E. M., Elthon D., Nicolas A. (eds). Ophiolites and oceanic crust: new insights from field studies and the ocean drilling program: Boulder, Colorado, vol. 349. Geological Society of America Special Paper 2000, pp 321–330.

Pearce, J. A. & Reagan, M. K. Identification, classification, and interpretation of boninites from Anthropocene to Eoarchean using Si-Mg-Ti systematics. Geosphere 15, 1008–1037 (2019).

Woelki, D., Regelous, M., Haase, K. M., Romer, R. H. & Beier, C. Petrogenesis of boninitic lavas from the Troodos Ophiolite, and comparison with Izu–Bonin–Mariana fore-arc crust. Earth Planetary Sci. Lett. 498, 203–214 (2018).

Reagan, M. K. et al. Fore‐arc basalts and subduction initiation in the Izu‐Bonin‐Mariana system. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 11, Q03X12 (2010).

Furnes, H., De Wit, M. & Dilek, Y. Four billion years of ophiolites reveal secular trends in oceanic crust formation. Geosci. Front. 5, 571–603 (2014).

König, S. et al. Boninites as windows into trace element mobility in subduction zones. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 684–704 (2010).

Huang C-C. Age and geochemical constraints on igneous rocks from Dai island, Eastern Indonesia: Discovery of Oligocene island arc tholeiitic magmatism. Master thesis, National Taiwan University, 2022.

Hall, R. Late Jurassic–Cenozoic reconstructions of the Indonesian region and the Indian Ocean. Tectonophysics 570, 1–41 (2012).

Kadarusman, A., Miyashita, S., Maruyama, S., Parkinson, C. D. & Ishikawa, A. Petrology, geochemistry and paleogeographic reconstruction of the East Sulawesi Ophiolite, Indonesia. Tectonophysics 392, 55–83 (2004).

Zhang, X. et al. A Late Miocene magmatic flare-up in West Sulawesi triggered by Banda slab rollback. Geolog. Soc. Am. Bullet. 132, 2517–2538. (2020).

Tien C-Y. Age and geochemical constraints on Cenozoic magmatic evolution in Southern Sulawesi. Master thesis, National Taiwan University, 2018.

Hall, R. & Spakman, W. Mantle structure and tectonic history of SE Asia. Tectonophysics 658, 14–45 (2015).

Miller, M. S. et al. Inherited lithospheric structures control arc-continent collisional heterogeneity. Geology 49, 652–656 (2021).

Schliffke, N., van Hunen, J., Gueydan, F., Magni, V. & Allen, M. B. Curved orogenic belts, back-arc basins, and obduction as consequences of collision at irregular continental margins. Geology 49, 1436–1440 (2021).

Elthon, D. Geochemical evidence for formation of the Bay of Islands ophiolite above a subduction zone. Nature 354, 140–143 (1991).

Cluzel, D., Meffre, S., Maurizot, P. & Crawford, A. J. Earliest Eocene (53 Ma) convergence in the Southwest Pacific: evidence from pre‐obduction dikes in the ophiolite of New Caledonia. Terra Nova 18, 395–402 (2006).

Singh, A. K., Chung, S. L. & Somerville, I. D. Petrogenesis of mantle peridotites in Neo‐Tethyan ophiolites from the Eastern Himalaya and Indo‐Myanmar Orogenic Belt in the geo‐tectonic framework of Southeast Asia. Geolog. J. 57, 4886–4919 (2022).

Dilek, Y. & Furnes, H. Structure and geochemistry of Tethyan ophiolites and their petrogenesis in subduction rollback systems. Lithos 113, 1–20 (2009).

Patriat, M. et al. Subduction initiation terranes exposed at the front of a 2 Ma volcanically-active subduction zone. Earth Planetary Sci. Lett. 508, 30–40 (2019).

Yumul, G. P. Jr et al. Slab rollback and microcontinent subduction in the evolution of the Zambales Ophiolite Complex (Philippines): a review. Geosci. Front. 11, 23–36 (2020).

Yu, M. et al. Slab-controlled elemental–isotopic enrichments during subduction initiation magmatism and variations in forearc chemostratigraphy. Earth Planetary Sci. Lett. 538, 116217 (2020).

Dycoco, J. M. A. et al. Juxtaposition of Cenozoic and Mesozoic ophiolites in Palawan island, Philippines: new insights on the evolution of the Proto-South China Sea. Tectonophysics 819, 229085 (2021).

Lin, C. T., Harris, R., Sun, W. D. & Zhang, G. L. Geochemical and geochronological constraints on the origin and emplacement of the East Taiwan Ophiolite. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 20, 2110–2133 (2019).

Yu, M., Yumul, G. P. Jr, Dilek, Y., Yan, Y. & Huang, C.-Y. Diking of various slab melts beneath forearc spreading center and age constraints of the subducted slab. Earth Planetary Sci. Lett. 579, 117367 (2022).

Keenan, T. E. et al. Rapid conversion of an oceanic spreading center to a subduction zone inferred from high-precision geochronology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 113, E7359–E7366 (2016).

Wu, J., Suppe, J., Lu, R. & Kanda, R. Philippine Sea and East Asian plate tectonics since 52 Ma constrained by new subducted slab reconstruction methods. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 121, 4670–4741 (2016).

Chiu, H.-Y. et al. Zircon U–Pb age constraints from Iran on the magmatic evolution related to Neotethyan subduction and Zagros orogeny. Lithos 162, 70–87 (2013).

Griffin W. GLITTER: data reduction software for laser ablation ICP-MS. In: Sylvester P. J. (ed). Laser Ablation-ICP-MS in the Earth Sciences: Current Practices and Outstanding Issues vol. 40. Mineral. Assoc. Canada Short Course, 2008, pp 308–311.

Andersen, T. Correction of common lead in U–Pb analyses that do not report 204Pb. Chem. Geol. 192, 59–79 (2002).

Ludwig K. Isoplot version 4.15: a geochronological toolkit for microsoft Excel. Berkeley Geochronology Center, Special Publication 2008: 247–270.

Horstwood, M. S. et al. Community‐derived standards for LA‐ICP‐MS U‐(Th‐) Pb geochronology–uncertainty propagation, age interpretation and data reporting. Geostand. Geoanalytical Res. 40, 311–332 (2016).

Lin, I.-J. et al. Geochemical and Sr–Nd isotopic characteristics of Cretaceous to Paleocene granitoids and volcanic rocks, SE Tibet: petrogenesis and tectonic implications. J. Asian Earth Sci. 53, 131–150 (2012).

Sun, S.-S. & McDonough, W. F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: implications for mantle composition and processes. Geol. Soc. London, Special Publ. 42, 313–345 (1989).

Acknowledgements

Detailed and constructive comments from the editors (Maria Laura Balestrieri and Joe Aslin) and reviewers are greatly appreciated. We thank Y. Kaneko, K. Okamoto and T. Tsujimori for help with fieldwork, H. Wang for mineral separation, Chien-Hui Hung, Chiu-Hong Chu and You-Jhen Chen for lab assistance, and Chetan L. Nathwani and George S. Burr for language editing of the manuscript. All samples were collected in the late nineties when there was no requirement of sampling permissions. YCL acknowledges Julian Pearce and Jamie Wilkinson for their supports to her stay in the Natural History Museum, London. This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (grant no. 110-2917-I-564-001) to YCL, for her 10-month academic visit in NHM, London, and by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (grant no. 110-2116-M-001-016-MY3) and Academic Sinica, Taiwan (grant no. AS-IA-104-M02) to SLC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YCL performed the data analysis and visualized the data. YCL and SLC wrote the manuscript. SM and AK designed the fieldwork and collected samples. HYL helped with the data acquisition. All authors contributed ideas to the interpretation of results or manuscript revisions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Maria Laura Balestrieri and Joe Aslin. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, YC., Chung, SL., Maruyama, S. et al. The ephemeral history of Earth’s youngest supra-subduction zone type ophiolite from Timor. Commun Earth Environ 4, 308 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00973-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00973-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.