Abstract

The Chinese traditional educational primer San Zi Jing (三字经) was immensely appreciated by Western missionaries, who frequently leveraged it to spur Chinese-language learning or to decipher Chinese thought. Walter Henry Medhurst (1796–1857), affiliated with the London Missionary Society (LMS), translated and reconstructed biblical scriptures into the format and style of the Chinese-language San Zi Jing, henceforth referred to as the “disguised San Zi Jing” in this article. The disguised San Zi Jing was initially published in Batavia in 1823 and reprinted in several locations, occasionally with minor modifications to its content. First, this study examines the complex qualities of the original San Zi Jing, which made it an ideal translation target, and the unique natures of the disguised San Zi Jing, which served as the ultimate translation product. Second, referencing Edward Said’s traveling theory, a diachronic investigation finds that the disguised San Zi Jing traveled in four stages, from Nanyang to Lingnan to Jiangnan and finally across Pan-China (more regions of China). Last, the article examines the indigenization process of the disguised San Zi Jing in space and content over time and analyzes the power dynamics underlying indigenization. The study contributes to translation history studies as well as studies of Christianity in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The London Missionary Society (LMS) was founded in 1795, intending “to spread the knowledge of Christ among heathen and other unenlightened nations” (Horne, 1895). Its missionary efforts gradually expanded to Asia, especially Southeast Asia, located to the south of China, as well as North America and South Africa. Among these places, China was recognized as an essential territory where “the most influential societies should direct their effort” (Medhurst, 1838). Robert Morrison was the first LMS missionary to associate with Chinese people. He arrived in Penang in 1805, followed by his colleague William Milne, who entered China in 1813. Before setting out for their missionary enterprises, Morrison and Milne received theological education at the Gosport Academy, where a theological training program was developed, placing a missionary emphasis on translating the Bible and other Christian tracts into local languages (Daily, 2013). Aware of the restrictions placed on missionaries working within China, they established the Ultra-Ganges Missions (恒河外方传教会), which extended from Morrison’s outpost on the south-eastern coast of China to the British colonial bridgeheads at the Malayan Strait, to the Dutch-controlled island of Java, and beyond (Laamann, 2022). Subsequently, not enough missionaries were available to support their project in this region, as addressed in Morrison’s letter to the LMS requesting more missionaries. In this context, Walter Henry Medhurst (1796–1857), much influenced and encouraged by Morrison and Milne’s missionary endeavors abroad, was urgently dispatched to Asia as a printer and reached Malacca in 1817.

Over two decades in Southeast Asia, Medhurst was fully committed to missionary enterprises. One of his responses to the intricate missionary environments in Asia was translating Western religious tracts in the format and style of the Chinese San Zi Jing, a typical primer used in Chinese schools to educate children with Confucian ideals. In this study, the disguised San Zi Jing is used to differentiate Medhurst’s translation from the Chinese San Zi Jing. Broadly in conformity with the four stages in Edward Said’s traveling theory, the disguised San Zi Jing demonstrated a south-to-northFootnote 1 transmission after its inception, moving roughly from Nanyang to Lingnan to Jiangnan and then to most major parts of China. Its travel highlighted the indigenization of Christianity in China spatially and textually with the passing of time. Therefore, this study, inspired by Edward Said’s traveling theory, illuminates the translational natures of the Chinese San Zi Jing as the translation target and the disguised San Zi Jing as the translation product by situating the latter within the framework of translation studies. The study traces the four-stage circulation of the disguised San Zi Jing by placing it in a historical context and thereby explains the power dynamics behind the indigenization of Christianity in nineteenth-century China.

Theory, methodology, and research questions

Traveling theory Footnote 2

In his book The World, the Text, and the Critic, Edward Said claimed that “like people and schools of criticism, ideas, and theories travel—from person to person, from situation to situation, from one period to another” (Said, 1983). In other words, ideas and theories have undergone varied degrees of change since their inception. It is noteworthy that ideas and theories, in the course of their travels, undergo varieties of change in response to diverse demands and adopt entirely new appearances. Additionally, Said stated that traveling ideas and theories go through the following four stages: a point of origin, a distance traversed to another time and space, acceptance or resistance, and finally, full or partial accommodation or incorporation in a new time and space (Said, 1983). Consequently, when discussing ideas and theories, special attention should be given to these four stages, as well as such aspects as the intricate conditions of their production, the routes of transmission they take, and the unique historical context in which they are received (Davis, 2014).

Even though the disguised San Zi Jing, a compendium of Western religious concepts, cannot be casually categorized as a “theory”, a rough classification into “ideas” is possible. Our investigation reveals that Medhurst’s translation generally experienced transmission through the following four stages: a point of origin, the distance traversed, acceptance, and accommodation. These qualities coincidentally align with those in Said’s traveling theory. As a result, the core ideas of the disguised San Zi Jing are classified as “ideas”, with the intent of legitimately characterizing its northward circulation with Said’s four-stage concept.

Methodology

Using the disguised San Zi Jing as the typical case, a descriptive approach is employed to describe the translation, transmission, and indigenization of Christianity in 19th-century China. Since previous studies tend to present the disguised San Zi Jing as a rewriting of Christian tracts (Leonard, 1985; Starr, 2008), imitative works by Western missionaries (Zou, 2009), Chinese-language Christian tracts for the less educated or children’s textbooks (Starr, 2008; Si, 2010; Guo, 2022), this study first briefly clarifies the translational nature of the Chinese San Zi Jing, paving the way for an elaboration on the natures of the disguised San Zi Jing as a translation product. Second, by investigating the disguised San Zi Jing in its specific political, social, and cultural contexts, the study diachronically explores the four-stage transmission of the disguised San Zi Jing with Said’s traveling theory, aiming to boost the comprehensive understanding of its south-to-north circulation. Finally, the power dynamics between imperial powers and colonial powers underlying the indigenization of Christianity in nineteenth-century China are analyzed through the lens of the translation and transmission of the disguised San Zi Jing.

Research questions

The study aims to answer the following questions:

-

Why did Medhurst translate Western scriptures into the format and style of the Chinese San Zi Jing, and what characteristics does his translation possess?

-

What characteristics does Medhurst’s disguised San Zi Jing display during its four-stage transmission?

-

How does the indigenization of Christianity in 19th-century China manifest in the translation and circulation of Medhurst’s disguised San Zi Jing? What power relationships lie in the indigenization process?

Translational natures of both the original San Zi Jing and the disguised San Zi Jing

Categorizing the disguised San Zi Jing as a translation

In contrast to studies that tend to consider the disguised San Zi Jing as rewriting, a compilation, or a textbook, this study situates the disguised San Zi Jing within the framework of translation studies as a translation by the LMS missionary W. H. MedhurstFootnote 3. Since translation has a long history dating back thousands of years and its characteristics vary depending on the concrete social, political, cultural, and ideological contexts, it is important to conceptualize translation in a dynamic and negotiated way. The definitions of translation are exhaustive in terms of language, culture, and technology due to terminological inflation in recent decades. Nevertheless, this study adopts the metaphor of a “bridge” from Rainer Schulte’s article What Is Translation? to underline the fundamental purpose of translation.

As we cross the bridge from one language or culture to another, a series of considerations come into play. We begin the crossing of the bridge with the social and cultural baggage of the original cultural landscape.

In a deeper philosophical sense, translation deals with the challenge of carrying complex moments across language and cultural borders, and, therefore, translators always navigate in realms of uncertainty.

(Rainer Schulte, 2012)

The quote above establishes a vivid metaphor emphasizing the intricate web of cultural and social boundaries that must be traversed to produce a high-quality translation. The metaphor can also shed light on Medhurst’s attempts to transcend the social and cultural barriers between the East and the West in his disguised San Zi Jing. Therefore, in light of the significant overlaps between a portion of the definitions of translation and the disguised San Zi Jing, the framework of translation studies is used to conduct an integrated text-and-context exploration that highlights the intricate contexts in which the text’s south-to-north travel occurred.

The original San Zi Jing’s complicated nature as a translation target

Medhurst’s disguised San Zi Jing was accomplished in the format and style of the traditional Chinese primer San Zi Jing by considering a number of factors; for example, the Chinese San Zi Jing’s intrinsic nature in content, format, and culture.

Nature in content

Pedagogical

The Chinese San Zi Jing played a significant part in educational primers with countless pedagogical implications. Children’s primers constituted an integral part of Chinese elementary education since antiquity, and three books—Qian Zi Wen千字文, San Zi Jing 三字经, and Bai Jia Xing百家姓—had gained dominance since the Song dynasty (Rawski, 1985). In particular, San Zi Jing, composed of about 1200 Chinese characters in three-character rhyming couplets, bore the responsibility of fostering moral values in children and molding them into respectable, ethical individuals. In this regard, translating Western religious tracts in the format and style of the Chinese San Zi Jing was an excellent method choice for taking advantage of its irreplaceable role in China’s elementary education and facilitating the propagation of the Christian gospels.

Linguistic

The Chinese San Zi Jing provided beginner readers and learners with a basic vocabulary of Chinese characters. The three primers listed above were combined to present a vocabulary of around 2000 Chinese characters, but San Zi Jing accounted for approximately half of this total. More importantly, San Zi Jing was composed in simple sentences with the support of its vocabulary, making it easier for young readers to comprehend, memorize, and grasp than the vast volumes of Jing (经) written in classical Chinese that used complex Chinese characters and complicated sentence structures. Furthermore, Chinese historical youth saw opportunities to manage challenging materials by coming home with a strong vocabulary (Rawski, 1985). Therefore, translating religious tracts in the format and style of the Chinese San Zi Jing served two purposes: (1) it helped to spread Christian doctrines among young and less-educated Chinese; (2) it worked as language-learning material for missionaries who were eager to learn Chinese to communicate with potential Chinese converts.

Nature in format

Printable and portable

As an instructional pamphlet, the Chinese San Zi Jing enabled both large-scale printing and itinerant preaching. On the one hand, its condensed content allowed large-scale printing despite the limitations of printing technology and the paucity of funding. On the other hand, the Chinese San Zi Jing’s small size combined with its condensed content presented a portable tract that was typically produced in dozens of pages and could be carried along on long trips. The translation of Christian doctrines into the format of the Chinese San Zi Jing took advantage of these two benefits so that missionaries could carry portable printed translations in parcels to disseminate tracts and preach orally in more places.

Nature in culture

Canonical

The Chinese San Zi Jing was celebrated as a canonical educational primer for hundreds of years. Medhurst believed that Christian missions were overcome by frustration in China partly because the Chinese people were pessimistic about the prospect of Western civilization in China. It was thus vitally important for missionaries to inform them of Western civilization with Christianity included (Leonard, 1985). Nevertheless, in light of the significant linguistic and cultural divide that existed between China and the West, the transmission of ideas was never simple to complete. Consequently, these two challenges demanded novel solutions since many of Medhurst’s forerunners had exerted much effort without achieving the desired result. In this setting, translating religious tracts into the form of canonical Chinese works could be a good way to empower the translation and reassure Chinese readers that, when translated with an appropriate approach and presented in a suitable format, Western religious civilization could, to some extent, rival that of China. Thus, the Chinese San Zi Jing was unsurprisingly chosen as the finest option, as it was distinguished by its canonical status in China.

Widespread

The Chinese San Zi Jing was incredibly popular among both children and adults who were once exposed to it. Many Chinese people, mostly from Canton and Fukien, traveled to and settled in the Nanyang area for a variety of reasons in the late Qing era. Despite the fact that the majority were unable to obtain a decent education, their Chinese heritage provided them with opportunities to receive an official or unofficial elementary education through resources like San Zi Jing. Additionally, through a combination of school education and word-of-mouth dissemination, their descendants became acquainted with the format and content of the Chinese San Zi Jing. In other words, the Nanyang area, which functioned as the testing ground for the missionaries and the gateway to China in the early 19th century, witnessed the great popularity of the Chinese San Zi Jing among adult immigrants and their offspring. In this context, translating Western biblical scriptures into the format of the Chinese San Zi Jing was expected to achieve the following two goals: (1) it would facilitate the dissemination of Christian gospels in the Nanyang area; (2) it could test whether such an approach was effective for missionary aims, and if the response was positive, it could then be utilized to aid missionary work in China in the future.

The disguised San Zi Jing’s particular nature as a translation product

Nature of ambiguity

The disguised San Zi Jing highlights the following two qualities as a translation product: ambiguity and disguise. The former appears in both the source and target texts. Ambiguity in the source text originated from the fact that disguised San Zi Jing was not translated verbatim from one source but rather from a collection of extracts from Bible-based Western religious texts. The extracts with Christian teachings were compiled to succinctly and clearly exhibit the basic ideas of Christianity.

In the beginning God created heaven, and earth...And God created man to his own image...And God blessed them, saying: increase and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it, and rule over the fishes of the sea, and the fowls of the air, and all living creatures that move upon the earth…And God saw all the things that he had made, and they were very good...

(Genesis, 1:1)Footnote 4

化天地, 造万有, 及造人, 真神主

无不在, 无不知, 无不能, 无不理

(Medhurst, 1843)

For instance, the opening lines in the disguised San Zi Jing above emphasized God’s power to create and save, which could be viewed to a great extent as a translation of part of Genesis in the Bible. However, the translated text omitted an explanation of how God created and saved the people in favor of highlighting several keywords in Christianity, such as “body (身体)”, “soul (灵魂)”, “flesh (肉)” and “spirit (灵)”, which were extensively mentioned in Western religious pamphlets (Si, 2010). In this sense, the text could be regarded as a translation of many Christian scriptures. In addition, it is difficult to trace some content in the disguised San Zi Jing to specific religious tracts due to numerous complex factors. As a result, the source text of the disguised San Zi Jing contains great ambiguity.

Ambiguity in the target text is derived from its ambiguity in the source text. It is consensus that the translator creates a link between the source and target texts. The link can be strong in certain situations, such as word-for-word translations, or weak in other situations, such as sense-for-sense translations. Whether it is strong or weak can be determined by placing the two texts in parallel to see if they are holistically matched by word or by sense. Nevertheless, it is challenging to identify the link between the disguised San Zi Jing and its source text, let alone the strength of the link, given the following two factors: (1) the source text of the disguised San Zi Jing cannot be attributed to any single specific text since it is a mixture of religious tracts; (2) the target text was produced by formatting the source text into the style of the Chinese San Zi Jing. Medhurst’s translation to spread Christianity exhibits such profound ambiguity in its link to the source text that “disguised” is justified in describing it.

Nature of disguise

The ambiguity in both the source and target texts contributes to the other characteristic of Medhurst’s translation of religious tracts: disguise. Lai (2012) employs the vivid phrase “in Chinese costume” to characterize “the popular English tracts” that “were translated into Chinese” by Protestant missionaries who were mainly dispatched from the Anglophone countries to disseminate the Christian message. These publications were “in Chinese costume” as they were not only translated from English tracts into Chinese but also made extensive reference to Chinese literature and culture to encourage in-depth comprehension. Medhurst’s translation of religious tracts basically accords with Lai’s expression, thereby, we draw inspiration from the phrase “in Chinese costume” and use the single adjective “disguised” to describe Medhurst’s translation. The nuance lies in the fact that the translations defined by Lai had specific source texts, for example, Philosophy of the Plan of Salvation was first translated by Timothy Richard and entitled Jiushi dangran zhili (救世当然之理), whereas a specific source text could not be traced for Medhurst’s translation. In other words, Medhurst’s translation revealed a “veiled” quality. Consequently, “disguised” is adopted to underline the difference in portraying Medhurst’s translation as the “disguised San Zi Jing”.

Regardless of the previous classifications, we categorize Medhurst’s translation of Western religious tracts into Chinese as a translation with a “disguised” nature and place it within the framework of translation studies. Two concerns about the disguised San Zi Jing at its translational level—why it was translated in the format and style of the Chinese San Zi Jing and what characteristics it had as a translation—are addressed in the analysis above, opening the avenue for a sketch of the route that it took in its four-stage dissemination from south to north.

Transmission of the disguised San Zi Jing from South to North in four stages

Drawing inspiration from Edward Said’s traveling theory, which emphasizes the dissemination of theories or ideas in four stages, this study finds that the travel of the disguised San Zi Jing is substantially in accordance with this pattern. Placing the disguised San Zi Jing in its historical context, this section examines the specific geographical, political, and cultural contexts in each stage that facilitated the creation, transmission, and adaptation of the text. This section also articulates the characteristics that the disguised San Zi Jing displays in its travel from south to north, laying the groundwork for further analysis of the power dynamics driving its dissemination.

A point of origin

Edward Said defines “a point of origin” as a set of initial circumstances in which the idea came to birth or entered discourse (Said, 1983). In this sense, Nanyang, which includes places like Batavia, Malacca, and Singapore, is the genuine birthplace of the disguised San Zi Jing. Nanyang was able to witness the creation of the disguised San Zi Jing for the following reasons. First, the Qing court’s prohibitions prevented Western missionaries from entering mainland China prior to the First Opium War (1839–1842). Even short-term stays in the port of Guangzhou were strictly forbidden (Xiong, 2010). The missionaries were thus compelled to establish new grounds to continue their enterprises. Geographically, Nanyang was not distant from China. Culturally, it had a sizable Chinese immigrant population. Politically, certain regions were controlled by the Dutch and Britain, among other European countries, either at the time or previously, and many restrictions imposed in this region were actually in favor of missionary work. In this setting, Medhurst’s forerunners, Morrison and Milne, moved to Nanyang, where the printing station was founded, and the Ultra-Ganges Missions were established to continue their work. Later, a lack of printers forced the LMS to dispatch skilled printers to help with publications. In 1817, Medhurst, an accomplished printer who was enthusiastic to work in a foreign land, was dispatched to Malacca to assist with printing. That same year, he was assigned to oversee nearly all of the missionary work in Nanyang after Milne left for Guangzhou to rest (O’Sullivan, 1984).

In Nanyang, Medhurst developed from an experienced printer to a qualified missionary proficient in Chinese and shouldered an array of missionary responsibilities. In particular, he placed an emphasis on children’s education and itinerant preaching. To educate local children in a clear and concise manner, he assembled a number of works in Chinese, including the Geographical Catechism (地理便童略传), the Child’s Primer (小子初读易识之书课), and A Catechism for Youth (幼学浅解问答), aiming to provide children with knowledge about the world. Between 1819 and 1822, he traveled to Penang and Batavia, and even descended into rural areas to deliver pamphlets as an itinerant preacher. His experience demonstrated that pamphlets were welcomed and worked for education and preaching, which motivated him to contemplate a pamphlet that could combine both pedagogical and religious functions. In this context, he resorted to Chinese primers and decided to translate Western religious scriptures into the format and content of the Chinese San Zi Jing; he thus produced the disguised San Zi Jing, as termed in this study.

The disguised San Zi Jing was first published in 1823 in Batavia. The body, composed of 16 pages with 948 total words, is described as “creative with an assonant, regulated flow of speech, in a clapper beat text” (Starr, 2008). It comprised a diverse array of themes intricately linked to Christianity, aiming to instruct the readers to “follow God’s law, act rightly, read and obey scriptures, receive baptism and communion” (Starr, 2008). In the years to come, the disguised San Zi Jing underwent minor linguistic or book-size alterations, but its overall structure and content remained consistent with the first edition.

During his years in Nanyang, Medhurst was tasked with presiding over the missionary work. In certain cases, he ventured outside of Batavia to places like Malacca, Penang, and Singapore, where the disguised San Zi Jing was reprinted for use as a textbook in local schools and for his use in itinerant preaching. Additionally, Sophia Martin’s Trimetrical Classic for Girls (训女三字经), a version designed by Sophia Martin (马典娘娘) to educate young women, was printed in 1832 in Singapore (Martin, 1832). Martin’s text “promoted a more gendered agenda, combining instruction on the value of female learning with theological input which paralleled the standard (i.e. male) texts” (Starr, 2008). Sophia Martin was Medhurst’s sister-in-law and taught women in Singapore at that time (Wylie, 1867). Her creation of the Trimetrical Classic for Girls was deemed to be a parallel under the influence of Medhurst (Xu, 2014).

In conclusion, complicated political, cultural, and geographical circumstances gave birth to the disguised San Zi Jing, which served as the carrier of Christian doctrines. Besides, we see that, before departing Nanyang, the disguised San Zi Jing experienced internal travel in areas such as Malacca and Singapore, where it was driven by Medhurst’s adaptable missionary strategies.

A distance traversed to another time and space

Edward Said argued that a distance traversed refers to “a passage through the pressure of various contexts as the idea moves from an earlier point to another time and space where it will come into a new prominence” (Said, 1983). Twenty years after its creation, the disguised San Zi Jing traveled a great distance to LingnanFootnote 5 as the First Opium War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Nanking.

Politically, the Treaty of Nanking forced China to open five ports (Shanghai, Canton, Ningpo, Foochow, and Amoy) to residence by British subjects and ceded Hong Kong to Britain (Fairbank, 1953). Thus, the LMS missionaries were granted a great deal of latitude to work in the cities that were opened to the British (DeBernardi, 2011). Geographically, on the one hand, Lingnan’s proximity to Nanyang made it easier for the missionary group to relocate their printing apparatus. On the other hand, Hong Kong’s proximity to mainland China made it more convenient for the missionaries to expand their enterprises into Chinese cities and towns in the interior when conditions allowed. Culturally, due to their close connections with Lingnan immigrants in Nanyang, the missionaries were fairly familiar with the dialects, customs, and cultures of the Lingnan region. Religiously, since the opened ports along the coast of China were much more approachable than most inland towns, several missionaries worked covertly in the ports and even baptized some locals, establishing the groundwork for further missionary activities (Xiong, 2010). Personally, Medhurst had traveled to Guangzhou, part of the Lingnan region, in 1835 and even undertaken an expedition down the southeast coast of China to explore the possibility of performing missionary work in China, as well as to collect information about where their travels extended (Medhurst, 1838). In addition, in 1843, missionaries stationed in the recently opened ports gathered in Hong Kong to decide on an entirely new translation of the Bible, which Medhurst was also invited to as a consultant (Hanan, 2003). It was in this context that the disguised San Zi Jing was introduced to Hong Kong as part of the Lingnan region.

The Anglo-Chinese College (英华书院)Footnote 6 published the first edition of the disguised San Zi Jing in Hong Kong in 1843. Believed to be a compilation of the printed versions in Nanyang, the text continued to use the terms “神” or “神主” to translate “God”. The second edition employed the terms “主” and “天帝” to translate “God”; additionally, its rhyming was more sophisticated, and its phrasing more classical than the one published in 1843 (Guo, 2022). The changes in terms and style in the second edition can be attributed to the debate over the Bible translation, which sparked contentious discussion about issues of “term (术语)” and “style (风格)”. Medhurst held his own stance, preferring to translate “God” as “上帝” (Medhurst, 1848; Hong, 2022) and proposing a “high wenli (深文理)”, i.e. high level of literary Chinese employed translated version. Both preferences were soon reflected in his revised disguised San Zi Jing.

In summary, twenty years after its birth, the disguised San Zi Jing traveled over land and sea and finally arrived in Lingnan as a result of complex political, geographic, and religious circumstances. Thanks to Lingnan’s geographical location and cultural position, the arrival of the disguised San Zi Jing in this region served as a prelude to its subsequent circulation in JiangnanFootnote 7, where Shanghai would be its main hub, enabling its transmission to the vicinity of Shanghai.

Acceptance

According to Edward Said, “there is a set of conditions—call them conditions of acceptance or, as an inevitable part of acceptance, resistances—which then confronts the transplanted theory or idea, making possible its introduction or toleration, however alien it might appear to be” (Said, 1983). In 1843, missionaries moved to Shanghai and Ningpo in Jiangnan. In Ningpo, The Chinese and American Holy Classic Book Establishment (华花圣经书房) was founded in 1845 by missionaries from the American Presbyterian Mission. As its name suggested, the establishment aimed to propagate biblical doctrines by printing and distributing religious pamphlets. In 1846, The Trimetrical Classic Explained (三字经新增批注) was published by Divie Bethune McCartee based on the disguised San Zi Jing. However, McCartee deleted the passages on religious ceremonies and missionary practices that were included in the second half of the previous edition and added commentary in concise language to increase comprehension of the explanations (Guo, 2022). This version indicated that Medhurst’s disguised San Zi Jing was highly respected and exploited by his counterparts. Even missionaries from other societies adapted the original to create a new version of his work. Annotations, for instance, were included to assist in interpreting doctrine and preaching among the public.

In Shanghai, the LMS established the LMS Mission Press (墨海书馆) in 1843, which Medhurst operated. The Mission Press printed numerous religious booklets expounding on Christianity to accomplish its goals. The disguised San Zi Jing was among these publications for the following reasons. First, as the founder and head of the Mission Press, Medhurst naturally had profound influence over what publications were printed. Second, since its inception, the disguised San Zi Jing proved to be effective in missionary work. Third, due to the climate in and around Shanghai, which was calmer than Canton in the Lingnan area, itinerant preaching once again continued (Eicher, 2022). For example, in 1845, Medhurst disguised himself as a Chinese person to travel around Shanghai and recorded his experiences in diary form upon his return to Shanghai (Medhurst, 1850; Holliday, 2016). This resulted in a high demand for portable publications to assist itinerant preaching. Under such circumstances, the disguised San Zi Jing was a suitable choice and was printed by the Mission Press in 1851, using “上帝” and “主” to translate the term “God”. Later in 1860, the Shanghai vernacular San Zi Jing (上海土白三字经) was created by Reuben Lowrie in 1860 in response to the need for supporting materials for preaching among Shanghai locals.

In conclusion, the disguised San Zi Jing was admirably adapted and accepted in this stage. With an emphasis on its dual function for preaching and educating, an annotation-enhanced version was produced. In addition, a vernacular version was created to adapt to the increasing needs arising from specific geographical contexts.

Full or partial accommodation or incorporation in a new time and space

Edward Said contended that the now full (or partly) accommodated (or incorporated) idea is to some extent transformed by its new uses, its new position in a new time and place (Said, 1983). After the Second Opium War (1856–1860), more treaties were signed between the Qing court and Western forces, allowing more ports to be opened and various privileges guaranteed to the missionaries (Hevia, 2003). In this situation, missionaries traveled to northern China, and new churches or related institutions were founded to expand missionary enterprises in more regions of China. Traveling with them were the publications to spread Christianity, including the disguised San Zi Jing. In 1863, Henry Blodget published a version in Tianjin, which was a word-for-word translation of the Shanghai vernacular edition into the northern Chinese vernacular. In 1864, the London Missionary Society’s Hospital in Peking (京都英国施医院), established by LMS missionary Dr. William Lockhart in 1861, published a version based on the one printed by the Mission Press in 1851.

In addition, under the treaties signed after the Second Opium War, Hong Kong was declared a free port, where merchant ships were allowed to enter and exit freely; a commercial area was also opened up on the island, while the ratio of various circulating currencies in Hong Kong was specified, and offices and banks were opened. In this context, Hong Kong became a favorable place for missionaries to continue their work, as well as for religious pamphlets to spread. As a result, in 1856, 1857, and 1863, the Anglo-Chinese College printed the disguised San Zi Jing, known as Maishi Sanzijing (麦氏三字经). Those printed in 1857 and 1863 contained an added commentary by William Lobscheid, offering explanations for each character and sentence. Furthermore, more ports, such as Hankou in inland China, Shantou, and Foochow in the Lingnan Area, were forced open in this stage, which also provided opportunities for the circulation of the disguised San Zi Jing and its derivative versions.

In conclusion, the treaties signed after the two opium wars allowed the missionaries considerably more freedom to travel northwards. Therefore, derivative versions based on Medhurst’s disguised San Zi Jing were produced with modifications to adapt to new specific contexts. In addition, the disguised San Zi Jing continued to be highly appreciated by missionaries, and more versions were created in various places. Even though to satisfy changing needs, some were presented very differently from Medhurst’s original design, these new versions largely adhered to the original format and were essential publications to support their long-standing ministry across China.

Indigenization process of the disguised San Zi Jing in space and content over time

Medhurst’s disguised San Zi Jing, an essential instrument for Christian preaching, has endured the longest and has been published with the greatest number of editions among those tracts written by missionaries in the 19th century (Guo, 2022). Its acceptance in China should be attributed to many factors, including its distinctive format, its cross-border travel through multiple obstacles, as well as the missionaries’ concerted efforts to promote the indigenization of Christianity in China, which advanced gradually over time, space, and content. This indigenization process is representative of Christianity in China during the 19th century, and inherent to this process is the power relations between China and the West, or, more accurately, between the imperial and colonial powers.

Indigenization of the disguised San Zi Jing in space and content over time

Spatial level: Nanyang–Lingnan–Jiangnan–Pan-China

Two patterns were detected in the indigenization of the disguised San Zi Jing in space: one from a global perspective and the other from a local angle. Globally, the text traveled from south to north, taking the path from Nanyang to Lingnan to Jiangnan before spreading to Pan-China. The path coincided with that of the missionaries dispatched by the LMS as well as other societies. Locally, the disguised San Zi Jing traveled internally in Nanyang and Jiangnan in the following two patterns: internal diffusion travel and internal vertical travel.

Internal diffusion travel refers to the fact that when the disguised San Zi Jing arrived in Nanyang and Jiangnan, it traveled to their vicinities. In Nanyang, it was developed in Batavia and was widely utilized in school teaching and public preaching. Later, it traveled to the vicinity of Batavia to continue its functions in such cities as Malacca and Singapore in Nanyang. We might conclude that this journey followed diffusion patterns inside the Nanyang region, with Batavia serving as the main hub. Similarly, in Jiangnan, it was printed in copious quantities by the Mission Press in Shanghai and was widely deployed through itinerant preaching. Later, it made its way to the outskirts of Shanghai in adapted versions. We might argue that the journey followed a path of diffusion throughout Jiangnan, in which Shanghai served as the main hub. Internal vertical travel describes the roughly vertical route that the disguised San Zi Jing took in moving from South China to North China. This vertical motion differs from the overall transnational movement of the text as it went in an approximately vertical line on the map from south to north.

The transmission of the disguised San Zi Jing, on whichever route, was essential to the indigenization of Christianity in the 19th century in China. Owing to Medhurst’s perseverance in traveling north despite the difficulties, the disguised San Zi Jing was able to enter China. On the one hand, it might have immediately reached more native Chinese, giving them more opportunities to become informed of Christianity. On the other hand, more missionaries in China might have had access to it and then utilized it to educate and convert its intended audience, as well as to create customized and even new versions in response to their specific situations. All versions with the disguised San Zi Jing at their core contributed to the indigenization of Christianity in China.

Textual level: terminologies, annotations, vernacular versions, and book sizes

Indigenization in content was facilitated by a range of factors, including the varying terminology, the added annotations, the extended vernacular versions, and the transformed book sizes, all of which combined to promote the indigenization of Christianity in China in the 19th century.

First, it is widely acknowledged that Western tracts are loaded with religious concepts that affect whether accurate interpretations can be obtained. Translating them from English to Chinese is difficult since there are fewer parallels between these two different languages. Given that the disguised San Zi Jing aimed to preach the core doctrines of Western religion to the Chinese, the translation of key religious concepts was essential for better comprehension and communication. Proper translation of the term “God” had particular significance. In fact, the translation of this term had received special attention throughout the early years of the disguised San Zi Jing. For example, Guo (2022) found that, in contrast to the Batavia version created in 1823, the version thought to have been created in 1828 or 1832 used “神主”, a combination of “神” and “主”, to translate the term “God” because, as far as Medhurst was concerned, it was conducive to both the interpretation and reception of Christianity in China. This choice of term followed the understanding that “神” was highly worshiped in traditional Chinese culture. As the disguised San Zi Jing traveled from south to north, the question of the translation of “God” continued to garner attention and witnessed changes, partially due to issues raised in the translation of the Bible and partially due to the missionaries’ personal preferences. The term “God” was translated differently in almost all versions to make the disguised San Zi Jing far more contextually relevant and recognizable. The issue was not resolved until the version was published by the Mission Press in 1851.

Second, the book size changed in relation to the binding and layout according to the particular context, sometimes to minimize printing expenses and sometimes to help with large-scale local distribution or to encourage itinerant preaching. One version published by the Hospital in Peking, at 12.7 cm tall, was ideal to increase print runs while lowering printing costs (Guo, 2022). Another version published by the Mission Press, at 11.3 cm tall, had a small size advantageous for both local distribution and itinerant preaching around Shanghai. Third, annotations were added in some versions to expound key concepts and doctrines to help the intended readers fully comprehend the doctrine. Last, vernacular versions were purposefully created to communicate with people in their native tongues.

In summary, even though the initially disguised San Zi Jing was only approximately 20 pages and 1000 words, throughout its journey, it experienced a number of alterations, minor or major, including the variation of terminology, the addition of annotations, the expansion of vernacular versions, and the transformation in book size. These alterations tremendously contributed to the indigenization of the disguised San Zi Jing as it traveled from south to north.

Power dynamics positioning the indigenization of the disguised San Zi Jing

It took nearly 50 years since its inception for the disguised San Zi Jing to be widely accepted by both Chinese and missionaries in China. During this prolonged period, China witnessed a series of events, including the two opium wars, which resulted from the power asymmetry between China and the West and, in turn, exacerbated the asymmetry with a shift in power dynamics. It was in such complicated circumstances that the translation, transmission, and indigenization of the disguised San Zi Jing occurred; in particular, the power dynamics between China and the West had a significant impact on its travel from south to north. This section investigates the power dynamics between China and the West, or more broadly, between the imperial powers and the colonial powers, with a focus on the four-stage travel of the disguised San Zi Jing.

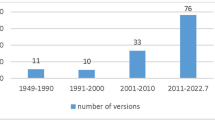

Figure 1 depicts the general south-to-north travel of the disguised San Zi Jing. Despite the fact that numerous derivative versions based on Medhurst’s translation arose during its transmission, the disguised San Zi Jing is centered on generating visual simplicity in the figure. The preceding section analyzed the four-stage travel of the disguised San Zi Jing from south to north, which followed the route: Nanyang—Lingnan—Jiangnan—Pan-China. Each stage spans approximately the following time periods: 1823–1842, 1843–1845, 1846–1855, and 1856–1875. The four periods trace the major events that occurred during that time and reveal the power dynamics between China and the West that underlay the journey of the disguised San Zi Jing.

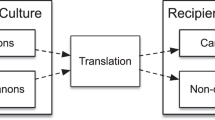

Figure 2 illustrates the above-mentioned power dynamics by leveraging a scale to demonstrate how they changed. The “distance end” refers to the distance that kept the disguised San Zi Jing away from China, while the “power end” refers to the power dynamics between China and the West, or more specifically, between the imperial and colonial powers. The balance shifts in accordance with the power asymmetry.

Stage One—Nanyang—spans from 1823 to 1842, a time period marked by the First Opium War. Prior to the war, the Qing court’s edicts forbade missionaries and publications from entering China and thus limited the distribution of the disguised San Zi Jing to the Nanyang region. When considering the situation from the standpoint of power dynamics, we find that the imperial powers held more weight than the colonial powers on the power end of the scale. As a result, the distance end of the scale tilts toward the power end, suggesting that the disguised San Zi Jing remained a considerable distance from China. However, such an imbalance was reversed with the start of the First Opium War and the subsequent signing of the Treaty of Nanking, which saw the imperial powers begin to give way to the colonial powers. Thus, the distance end of the scale tilts back to its own side. Such a change demonstrated that the distance of the disguised San Zi Jing from China was shortened. Because of the complex political, economic, and cultural agendas on both sides, the power dynamics between China and the West during this time shifted only gradually. Nevertheless, the shift in power dynamics during these two decades paved the way for the disguised San Zi Jing to approach and even set foot on Chinese soil, setting the stage for the following three stages.

Stage Two—Lingnan—spans from 1843 to 1845, a brief transitional period. For one thing, the arrival of the disguised San Zi Jing in Lingnan was arguably the result of the shift in power dynamics that followed the First Opium War in stage one. That is, the Qing court was still dealing with the aftermath of the war. Therefore, the power relationship during this time did not clearly change. For another, since the missionaries were eager to introduce Christianity to as many parts of China as possible, Lingnan, which is situated at the corner of the country, was never the sole or ultimate destination of the disguised San Zi Jing. Thus, following a brief sojourn in Hong Kong, which served as a main base for the missions and saw the publication of the disguised San Zi Jing by the Anglo-Chinese College, the text was transported northward by missionaries to a region where long-term contact between China and the West had been maintained and where several important ports were opened to foreigners. In this sense, this transitional period served as an antecedent to the dissemination and indigenization of the disguised San Zi Jing in more regions of China.

Stage Three—Jiangnan—spans from 1846 to 1855, a period marked as the prelude to the Second Opium War, while greatly influenced by the First Opium War. The travel of the disguised San Zi Jing to Jiangnan was linked to the shift in the balance of power between China and the West in the decade before the Second Opium War. If illustrated from the perspective of power dynamics, the scale tilts toward the distance end, indicating that the distance of the disguised San Zi Jing from China continued to be greatly shortened and that it not only entered China but also moved far away from its birthplace.

Stage Four—Pan-China—spans from 1856 to 1875, a period marked by the end of the Second Opium War and the signing of more treaties with Britain, France, and Russia. As previously mentioned, China suffered a series of negative events following the First Opium War, which worsened over time and eventually led to the Second Opium War. The second war forced China to open more ports, cede more territory, and grant more privileges to the Western powers. In this situation, the missionaries could travel to more places, and so did the disguised San Zi Jing, as well as its adapted versions. If explained from the perspective of power dynamics, the colonial powers far exceeded the imperial powers, and the distance end of the scale tilted towards its own end, showing that the distance was once again shortened.

Conclusion

In the early 19th century, Robert Morrison translated the Chinese San Zi Jing into English with the intention of using it as a tool to help missionaries learn Chinese and gain insights into Chinese philosophy, especially Confucianism (Morrison, 1812). His colleague W. H. Medhurst similarly utilized the Chinese San Zi Jing to fulfill his own goals after embarking on his missionary career. However, Medhurst made use of the text in a novel way by translating Western religious tracts into the format and style of the Chinese San Zi Jing, aiming to use such a translation as a tool for preaching among the Chinese and in China.

Previous studies tend to view Medhurst’s translation as a compilation of Western scriptures for proselytizing to children, a rewriting of religious pamphlets, or an imitation by Western missionaries while ignoring its intrinsic qualities as a translation. Therefore, this article highlights its function as a “bridge” connecting China and the West and categorizes it as a translation under the name of the disguised San Zi Jing. Placing the text within the framework of translation studies, this study concludes that Medhurst translated religious scriptures into the format of the Chinese San Zi Jing since it possessed unique qualities in terms of content, format, and cultural content. In content, the text was of great pedagogical and linguistic importance; in format, it offered benefits for printing and portability; and in culture, it was widely accepted and established among the Chinese people. These qualities came together to create a translation that featured ambiguity and disguise. Ambiguity arose from the inability to identify the source and target texts of Medhurst’s translation, which leads to the nature of disguise, which also explains the disparate definitions of its identities in earlier research.

Given the fact that the disguised San Zi Jing was a collection of Western religious ideas and traveled northwards to China, this study draws inspiration from Edward Said’s traveling theory, which emphasizes the transmission of ideas in four stages, to analyze the disguised San Zi Jing’s travel according to a corresponding four stages: a point of origin in Nanyang, a distance traversed to another time and space in Lingnan, acceptance in Jiangnan and finally accommodation in Pan-China. As Bassnett and Trivedi (1999) observed, “Translations are always embedded in cultural and political systems and in history”. This study thus elaborates on the complicated historical contexts in which the disguised San Zi Jing was created, circulated, adapted, and ultimately indigenized in China. Such indigenization is evident not only by its travel across time but also by its multilayered adjustments in terminology, annotations, vernaculars, and book sizes. Inherent to such a process of indigenization is the shift in power dynamics between China and the West, which resulted in changes in power asymmetry and allowed the disguised San Zi Jing to travel from south to north.

Notes

In this article, when utilized to describe the directional movement of the disguised San Zi Jing by W.H. Medhurst, “south” and “north” are not absolute geographical concepts, but flexible ones. When used to describe the cross-border movement between Southeast Asia and China, “south” and “north” are divided by the boundary. But when used to describe the movement within China, these terms follow the dividing line of South China and North China.

While taking inspiration from Said’s traveling theory and utilizing the four-stage concept throughout the study, this essay does not investigate its complicated intrinsic underlying mechanisms.

In some versions of the disguised San Zi Jing, for example, in Xinzeng sanzijing (新增三字经), the authorial signature on the first page is “尚德者”, a pseudonym of W.H. Medhurst. Since this nuance makes no difference to our analysis, Medhurst is used throughout this article.

The quote from Genesis in the Bible is taken from The Holy Bible, Translated From the Latin Vulgate: Diligently Compared With the Hebrew, Greek, and Other Editions, in Divers Languages, Douay-Rheims Version 1609 & 1582. Accessed at: http://triggs.djvu.org/djvu-editions.com/BIBLES/DRV/Download.pdf

According to He and Wu (2023), Lingnan describes the geographical region situated south of the Five Ridges in China, which historically comprised Guangdong Province and Southwestern Fujian Province.

In 1818, The Anglo-Chinese College (英华书院) was established in Malacca by Robert Morrison and William Milne with the aim of spreading the Christian gospels. In Malacca, the college served as both a school and a printing press for Chinese Bibles and Christian tracts, as well as sinological works. In 1843, the college was relocated to Hong Kong, where it still functioned as a school and a press.

Although the term “Jiangnan” is a historically variable concept and its geographic scope varies depending on the criteria of division, the two regions concerned in this study—Shanghai and Ningpo—were included in the Jiangnan area in the Qing dynasty.

References

Bassnett S, Trivedi H (1999) Introduction: of colonies, cannibals and vernaculars. In: Bassnett S, Trivedi H (eds.) Postcolonial translation: theory and practice. Routledge, London

Daily CA (2013) Robert Morrison and the Protestant plans for China. Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong

Davis K (2014) Beyond the canon: travelling theories and cultural translations. Eur J Women’s Stud 21(3):215–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506814529628

DeBernardi J (2011) Moses’s Rod: the Bible as a commodity in Southeast Asia and China. In: Tagliacozzo E, Chang WC (ed.) Chinese circulations: capital, commodities, and networks in Southeast Asia. Duke University Press, Cambridge

Eicher S (2022) Beyond Shanghai: the inland activities of the London Missionary Society from 1843 to 1860 according to Wang Tao’s diaries. Monum Serica: J Orient Stud 70(2):423–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/02549948.2022.2131810

Fairbank JK (1953) Trade and diplomacy on the China Coast: the opening of the treaty Ports, 1842–1854. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Guo H (2022) From children’s instructional textbook to missionary tool: the publication history of the Christian Three-Character Classic from 1823 to 1880. In: Tao FY (ed) Beyond indigenization: Christianity and Chinese history in a global context. Brill, Leiden

Hanan P (2003) The Bible as Chinese literature: Medhurst, Wang Tao, and the Delegates’ Version. Harv J Asiat Stud 63(1):197–239. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25066695

He Y, Wu R (2023) An exploration of the evolution of the Loong Mother Belief System in Lingnan: formation and transformation. Religions 14(9):1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091103

Hevia J (2003) English Lessons: the pedagogy of imperialism in nineteenth-century China. Duke University Press, Durham

Holliday J (2016) Mission to China: how an Englishman brought the west to the orient. Amberlay Publishing, Stroud, Gloucestershire

Hong X (2022) Maidusi dui God zhi hanyu yiming de sikaolicheng tanwei麦都思对 God之汉语译名的思考历程探微 (On W. H. Medhurst’s reflections on the Chinese translation of “God”). Zongjiaoxue Yanjiu 宗教学研究 (Relig Stud) 2:218–226

Horne CS (1895) The story of the L.M.S. (1795–1895). London Missionary Society, London

Laamann LP (2022) The Protestant missions to South-East Asia: experimental laboratory of missionary concepts and of human relations (circa 1780–1840). Exchange 51(3):266–286. https://doi.org/10.1163/1572543x-bja10005

Lai J (2012) Negotiating religious gaps: the enterprise of translating Christian tracts by Protestant Missionaries in nineteenth-century China. Institut Monumenta Serica, Sankt Augustin

Leonard JK (1985) W.H. Medhurst: rewriting the Missionary message. In: Barnett SW, Fairbank JK (ed.) Christianity in China: early protestant missionary writings. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Martin S 马典娘娘 (1832) Xun nü san zi jing训女三字经 (Three character classic, for the instruction of females). Singapore. https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/chinese-rare-books/catalog/49-990081504560203941

Medhurst WH (1838) China: Its State and Prospects, with especial reference to the spread of the gospel; containing allusions to the antiquity, extent, population, civilization, literature and religion of the Chinese. Crocker and Brewster, Boston

Medhurst WH (1843) San Zi Jing 三字经. Anglo-Chinese College, Hong Kong, (香港英华书院藏版)

Medhurst WH (1848) An inquiry into the proper mode of rendering the word God in translating the Sacred Scriptures into the Chinese language. Chin Rep 17(5):209–242

Medhurst WH (1850) A glance at the interior of China, obtained during a Journey through the Silk and Green Tea Districts: taken in 1845. John Snow, London

Morrison R (1812) Horæ Sinicæ: translations from the popular literature of the Chinese. Printed for Black and Parry, London

O’Sullivan L (1984) The London Missionary Society: a written record of missionaries and printing presses in the Straits Settlements, 1815–1847. J Malays Branch R Asiat Soc 57(2):61–104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41492984

Rawski ES (1985) Elementary education in the Mission Enterprise. In: Barnett SW, Fairbank JK (ed.) Christianity in China: early protestant missionary writings. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Said E (1983) The world, the text, and the critic. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Schulte R (2012) What is translation? Transl Rev 83(1):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/07374836.2012.703119

Si J (2010) Maidusi Sanzijing yu xinjiao zaoqi zaihua ji Nanyangdiqu de huodong 麦都思《三字经》与新教早期在华及南洋地区的活动 (Medhurst’s San Zi Jing: early Protestant’s activities in China and Nanyang). Xueshu yanjiu学术研究 (Acad Res) 12:112–119

Starr C (2008) Reading Christian scriptures: the nineteenth-century context. In: Starr C (ed.) Reading Christian scriptures in China. T&T Clark, London

Wylie A (1867) Memorials of Protestant missionaries to the Chinese: giving a list of their publications, and obituary notices of the deceased. American Presbyterian Mission Press, Shanghae

Xiong Y (2010) Xixuedongjian yu wanqingshehui 西学东渐与晚清社会(The Eastward dissemination of Western learning in the Late Qing Dynasty). China Renmin University Press, Beijing

Xu S(2014) Jidujiao chuanbo guocheng zhong de bentuhua tansuo基督教传播过程中的本土化探索——传教士中文作品《训女三字经》文本初探 (Indigenization in Christianity dissemination: a study on Xun nü san zi jing Written in Chinese by a Missionary) 金陵神学志 (Nanjing Theol Rev) 2(99):170–181

Zou Y (2009) Wanqing sanzijing yingyiben ji yejiaofangben jieyuansanzijing gaishu晚清《三字经》英译本及耶教仿本《解元三字经》概述 (An introduction to Four English translations of the “three character classic” and Imitative works by western missionaries in the Late Qing Dynasty). tushuguan luntan 图书馆论坛 (Libr Trib) 29(2):176–178

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Idea of the study was identified by PW and MX. The first draft of this manuscript was written by PW. MX proofread and commented on previous versions of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. both authors contributed to the manuscript revision and read and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, P., Xu, M. Translation, transmission and indigenization of Christianity in nineteenth-century China: south-to-north travel of the disguised San Zi Jing by Medhurst. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 474 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02981-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02981-y