Abstract

During the Cold War era, translation constituted an integral part of the ideological confrontations of US cultural diplomacy. Scholarly discussions on US-associated cultural products have provided insights from the perspective of American patronage, yet have not adequately addressed the diverse role of unofficial agencies in their cultural practices with multiple intentions. This study analyzes Chinese translations in the magazine Children’s Paradise (CP) operated by the Union, an entity involved in the network of American covert cultural diplomatic activities. It delves into the Union’s agenda of furthering a progressive Chinese nation that continues and revitalizes Chinese civilization by analyzing three marked characteristics of the translated texts and their underlying rationales. It finds that, through deliberate omissions, substitutions, and additions, CP demonstrated a relentless commitment to the Union’s China-centric agendas in its domesticated and adapted translations. Despite sharing the anti-communist conviction associated with American interests, CP leveraged localized practices to engage with the social-political issues of the British-ruled Hong Kong of the 1970s. As a result, it generated cultural outcomes exceeding the Cold War polarities, and left a lasting legacy on the younger generation of Hong Kong.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

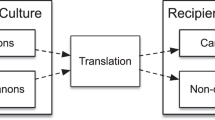

The Cold War era (1945–1989) was profoundly characterized by the use of translations to wage hidden ideological battles. On both sides of the Iron Curtain, translated publications, integral to cultural activities, were initiated and funded to win the hearts and minds of people, constituting an influential part of the Cold War cultural diplomacy (Lygo 2018, pp. 442–446). In the Asian context, the US government’s sponsorship of various translation campaigns aimed at establishing cultural dominance over communist and leftist ideologies has drawn wide scholarly attention, including an examination of the nexus between these translated products and the American propagation of Western values (Li 2013, 2022; Wang 2014, 2022; Wang 2020; Du 2022). Studies have commonly noted that translation efforts in Asia feature agencies implementing, disseminating and interacting with cultural diplomacy at different levels. These agencies were, in practice, the “players and funders” (Von Flotow 2018, p. 196), responsible for selecting, producing, publishing and marketing cultural productions. Nonetheless, when examined with a particular focus on American patronage, the agencies in question and their translated content were often perceived as aligned with the state interests, even though many translated material on their own terms and according to their own agendas.

The dynamic and diversified role of unofficial actors in cultural diplomacy, especially in their engagement with popular culture, is noteworthy. Jiang (2021) observed the “tensions” between non-governmental endeavors in online literature translation and Chinese governmental cultural diplomacy (p. 901). Similarly, in Japan, private sector initiatives in branding Japanese animation and lifestyle could later be “rejected, contested, endorsed, or co-opted” by official sectors (Otmazgin 2012, p. 40). Regarding pop culture during the Cold War, children-targeted translations, including literature and comics, mainly originated from semi-independent institutions or those free from governmental control, while achieving paramount “culturally diplomatic influences” (Von Flotow 2018, p. 198). However, as these cultural players “did not always carry out clear or unequivocal instructions” from official powers, their translation practices were more likely responsive to the multifaceted and localized contexts, rather than a monolithic top-down system (Popa 2018, p. 430). Lygo (2018) pointed out that both Soviet and British individual agencies in the Cold War “pursued their own agendas” through translations, “further(ing) their own causes” (p. 449). Therefore, discussions of pop cultural productions from non-official sectors, when conducted solely within the broad framework of one-sided patronage, risk generating insights that are both limited and simplistic.

This is particularly true in the academic discourse surrounding the cultural practices of the Union Organization (the Union hereafter) and its Chinese cultural product, Children’s Paradise (referred to as CP hereafter), which was the leading children’s magazine in Hong Kong during the Cold War. Within its pages, this child-centric periodical featured translations from Western picture books and Japanese manga (Fok 2010, p. 238), localizing both textual and visual elements to resonate with Hong Kong’s young readership (Fok 2011, pp. 148–149). Given that the Union was funded by the Asia Foundation, an entity associated with the US government’s covert operations in Asia, CP has long been understood in the context of the monolithic American anti-communist cultural campaigns (Wang 2016). Moreover, despite the insufficient textual exploration of CP, it is regarded as “green-spine” literature or a counter to “left-wing” literature (Wang 1998; Zhao 2018).Footnote 1 Yet, recent archival revelations and personal accounts challenge this oversimplified view, suggesting that there were no direct monetary ties between the periodical and the Asia Foundation, especially after the latter ceased all financial support to the Union in the 1970s (Lo and Hung 2014, p. 179, p. 186; 2017, p. 18). Intriguingly, it was during this same decade that CP “achieved paramount success” among Hong Kong’s young audience (Lo and Hung 2017, p. 214). This success, in Kang’s terms, can be interpreted as a result of “effective cultural policies” (cited in Jiang 2021, p. 901) implemented by the Union, representing a departure from a unilateral approach to practices of culture. Such a viewpoint necessitates a re-evaluation of CP, a cultural content deeply localized and managed by an agency with only a tenuous link to the US, urging an analysis that transcends the simplistic framework of American patronage.

To provide a fresh perspective, this study examines the translations of picture stories in CP, focusing on the Union’s agendas within the context of the Cold War-era Hong Kong in the 1970s. The cultural practices of this period were complicated by Hong Kong’s geopolitics, mainly involving Communist China, America, and the British colonial government. In this intricate socio-political environment, the Union’s cultural diplomatic activities, exemplified by CP’s translations for the young, merit an inclusive but locally focused view. This study begins with a historical overview of the interlink between the Union, its cultural outputs, and the Cold War Hong Kong through the lens of cultural diplomacy. This is complemented by a brief quantitative survey of picture story translations in CP. Following that, the article analyzes three recurring features of these translated texts which work in concert with the Union’s agendas, explicating the translation strategies and underlying rationales. These distinctive traits, as I argue, do not simply parrot American anti-communist sentiments. Rather, they mirror an evolved yet consistent interpretation of the Union’s overarching agendas in the Cold War cultural diplomacy, shaped by the socio-political landscape of Hong Kong during the 1970s.

The Union, its periodicals and the Cold War cultural diplomacy

Cultural diplomacy is considered “part of a government’s public diplomacy”, which, by means of arts and culture, augments a nation’s clout on the international stage (Von Flotow 2018, p. 193). In the Cold War era, marked by rivalry and confrontation between the Western capitalist bloc and the Eastern socialist bloc, the US government strategically employed cultural diplomacy worldwide, using fine arts and mass media to publicize American values and interests, while critiquing the tenets of communism. Nevertheless, its cultural diplomatic undertakings were not conducted in a homogenous or unified state-controlled manner but were substantially decentralized through a variety of clandestine institutions, most notably the United States Information Services and Asia Foundation, which operated across Asia (Li 2013, 2022; Wang 2014, 2022; Wang 2020). Tasked with covert, soft, and more effective forms of propaganda, the Asia Foundation did not conduct overt political operatives, but prioritized “cultural production and circulation” to “assist non-Communist” campaigns through “any and all media of communication” (Shen 2017, pp. 593–594). With an emphasis on “working with local Asian talents and resources” (Shen 2017, p. 594), it engaged varied local agencies (private corporations, NGOs, cultural and religious groups, etc.) as the actual practitioners of cultural activities (Wang, 2022, p. 573). With the Foundation’s support, these local entities disseminated pro-American literature, films, newspapers, and broadcasts (Wang 2020, p. 331). In Hong Kong, the Foundation forged connections with the Union, sponsoring its cultural activities to counter the ideological influence of communist China.

Established in Chongqing in 1944 under the name Youth Union for Democratic China, the Union relocated to Hong Kong by 1949 following the definitive rift between the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Kuomingtang (KMT). As one of the groupings of the Third Force, it did not fully agree with either side.Footnote 2 With a shared opposition to communism, the Union accepted subsidies from the Foundation starting in the early 1950s, evolving into an influential cultural entity (Fu 2019a, pp. 56–57). Among its endeavors funded by the Foundation, the establishment of the Union Press proved to be the most successful for “producing varied cultural content” (Zhao 2017, p. 168). Well-curated Chinese periodicals launched by the Union Press include China Weekly (1953–1964) for the general public, University Life (1955–1971) targeting university students, Chinese Student Weekly (1952–1974) for high schoolers, and CP (1953–1994) tailored for younger children. Operating largely on the periphery of state power, like many non-official cultural diplomacy agencies, Union’s cultural products were not “within an authorised and regulated sphere”, but instead enjoyed considerable “room for manoeuvre” and responded adaptively to “local contexts” (Popa 2018, p. 434). The common consensus asserts that the Foundation provided financial support for projects proposed by the Union’s liaison (usually a top staff member) without interfering in detailed editorial decisions, thus allowing full operational autonomy for the editorial office of each periodical (Lo and Hung 2014, p. 30, p. 66, p. 97; 2017, p. 57). This may be attributed to “the limited contact” between ordinary Union members and the Foundation, as well as to the Foundation’s greater focus on “circulation figures” it deemed useful, instead of “the magazine’s content” (Shen 2017, p. 604). Therefore, the Union retained significant freedom to pursue its agendas through cultural publications.

Originating from the perspectives of elite university students immersed in Chinese traditions, the Union envisaged an alternative democratic China rooted in genuine Chinese cultural values (Lin 2018, pp. 31–35). This vision diverged from the ideals of both the communist-led People’s Republic of China (PRC) on the Chinese mainland and the Republic of China (ROC) under the KMT in Taiwan. As Fu noted (2019b), throughout its signature periodical, the Chinese Student Weekly, run by the Union Press, the Union opposed both the CPC and KMT, and advocated the preservation and revival of Chinese cultural heritage (pp. 76–77). In light of this, it is safe to say that the Union took advantage of the Foundation-funded cultural publication to further its China-centric agendas, despite sharing an anti-communist conviction with American cultural diplomacy. Directed at the youngest children, CP served as the Union’s crucial cultural medium to inculcate its idealized version of the Chinese nation, because the younger generation was always “expected to lead its country’s march toward the future” (Otmazgin 2012, p. 39). To attract more child readers, picture stories of the enchanting popular culture were selected as the major genre in the biweekly CP (Fok 2011, p. 142, p. 162). The choice of pop culture turned out advantageous, as when other Union periodicals had to be discontinued in the 1970s due to dwindling readership and reduced financial backing from the Foundation, CP not only thrived but also persisted until the 1990s.

Compared to the hostility and chill between the US and the PRC in the 1950s, Sino-American relations warmed following President Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972. This rapprochement, based on common interests to contain the Soviet influence, altered the landscape of American cultural diplomacy in 1970s Hong Kong. Initially, the British colonial government, which had been silent but largely cooperative regarding American cultural initiatives in Hong Kong (Wang 2022, p. 570), became more proactive due to fears of Communist China, especially after the 1967 anti-government riots: a spillover of communist and leftist ideologies from the Chinese mainland. In response, the British colonizer launched an array of reforms to enhance the sense of belonging to and appreciation for Hong Kong among its colonized population (Cheung 2017, pp. 169–171), leading to a burgeoning of Hong Kong consciousness. Secondly, as American ties with the PRC normalized, the Asia Foundation ceased its financial support for the Union. This led to the closure of several of the Union’s anti-communist periodicals, which were already struggling to adapt to the shifting geopolitical situation in Hong Kong (Zhao 2017, p. 171). Nonetheless, despite the declining trajectory of the Union’s cultural products, CP “enhanced the content”, capturing the changed societal trend and realizing profits for self-sufficiency (Lo and Hung 2017, p. 190). Its translations, in particular, gained great popularity and have been remembered as a beloved childhood companion by the younger generation of that time.Footnote 3

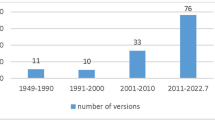

In light of the renewed backdrop of the Cold War’s 1970s phase in Hong Kong, where CP continued its cultural diplomatic activities, this context prompts inquiries into the nature of its translations. What characteristics defined these translations? What were the rationales behind them? How did they relate to the Union’s own agendas, as well as the evolving dynamics of American cultural diplomacy? These questions warrant in-depth exploration. Fok (2011, p. 142) suggested two to three picture stories would be translated in CP per issue, although no sources were provided. Through a factual survey, this study found approximately 120 translations with identifiable source texts in CP from 1970 to 1979, including some original titles outlined in Table 1. Translations, predominantly sourced from English and Japanese (of which there were 83 and 25 instances respectively), were regarded as “good and quality” reading material for children (Lo and Hung 2017, p. 197), given the well-developed early education in these countries, particularly Japan, where substantial resources are dedicated to making children’s content (Lo and Hung 2017, p. 198, p. 228).Footnote 4 To ensure a comprehensive and methodical assessment, my analysis mainly includes serialized stories spanning the periodical’s 1970s issues, such as Gulliver Guinea-Pig’s Adventure, The Little Bear, Dr. Seuss’s books and Doraemon.

Although each story in CP’s table of contents was attributed to an individual (pen names or pseudonyms), the content was, in fact, the product of collective efforts. In the 1970s issues, CP’s Editor-in-Chief Zhang Junhua took the lead in rendering the verbal content of the source texts (STs), whereas illustrators like Luo Guanqiao and Li Chengfa repainted the visuals based on the original work. Therefore, the translations being analyzed are approached as the joint endeavors of CP’s editorial team (as “CP” in text citations). A close examination of both verbal and visual elements in the target texts (TTs) reveals three salient characteristics.

Exclusion of the political and geographical “China”

The first recurring feature identified is the consistent exclusion of the term “China”: whenever “China” appeared in the STs, it was either elided or replaced in the TTs. This pattern was observed approximately ten times across the texts investigated in this study. Three instances have been analyzed here to illustrate the typical translation strategies of omission and substitution to exclude “China”.

The Adventure of Gulliver Guinea-Pig was initially published as nursery rhymes in Playhour, an English magazine targeting a young readership. Multiple episodes chart the journey of the protagonist, Gulliver, as he ventures through both real countries in the world and imaginative lands. When CP introduced them to Hong Kong readers, the editorial team presented them under the serialized title “Guinea-Pig” (“土撥鼠” in Chinese). For his real-world journeys sequenced in the 1976 and 1977 issues, while episodes like “Gulliver’s Hot Time at the North Pole” and “Gulliver Guinea-Pig and Sugar Sugar Cane in South America” were retained and translated, the episode entitled “Gulliver and the Chinese Prince” was absent from CP. This episode had a two-week run in Playhour starting with the issue dated 21 July 1962. It opens by pinpointing the geographical setting of China in the ST with “what a wonderful adventure he had in China, where…”, and later narrates Gulliver’s encounter with a Chinese Prince Loo Song in rescuing Princess Petal. Given that episodes published in the preceding and subsequent issues of Playhour were both translated in CP, the omission of this China episode seems unlikely to be a careless oversight, but a deliberate decision.

There is also omission of the term “China” in the translation of Little Bear’s Wish, an early reader penned by Else Minarik and adorned with illustrations by Maurice Sendak. In the ST, Little Bear shares with Mother Bear an array of whimsical wishes, which include floating on a cloud, discovering a Viking ship, traversing to China through a tunnel to get chopsticks, and driving a red car to meet a princess in a castle who offers him a cake. Each daydream is vividly depicted in a corresponding illustration (Minarik 1957/1985, pp. 52–56). In the TT, however, while all other fanciful daydreams were preserved in both textual and illustrative representations, the wish of “going all the way to China” – with “China” designated as the geographical location verbally and depicted with an image of a bear emerging from a tunnel to encounter another bear holding chopsticks – was taken away (CP tr 1971, p. 9). Given that CP’s illustrators always skillfully arranged illustrations to fit the available page space, as evidenced by the resized pictures of Little Bear’s other dreams compared to the ST, the omission of the China dream is unlikely to be a result of spatial constraints.

The translation of Dr. Seuss’s “The Big Brag” which appeared as “Bragging Competition” (“鬥吹牛” in Chinese) presents another instance of such exclusion. In the ST, an elderly worm seeks to humble a bragging rabbit and bear by claiming an exaggerated range of vision. This vision purportedly extends across the Pacific Ocean to Japan and China, then going further to Egypt, subsequently shifting northwards to Europe, and eventually looping back to Brazil in the Americas. These geographical boasts are visually represented, with labels of “Japan” and “China” prominently displayed on signposts (Dr. Seuss 1958, p. 42). Yet, in the TT, this visual and narrative trajectory undergoes a marked alteration: the vision crosses the Pacific Ocean, to Bolivia and Brazil, then spans the Atlantic Ocean to Saudi Arabia, India, and Pakistan, followed by some other Asian countries. Notably, the visual signposts in the TT were substituted with “Bolivia” and “Brazil” (“玻利維亞” and “巴西” in Chinese) (CP tr 1973, p. 25). The absence of “China” in this case can be interpreted as a strategic move: Dr. Seuss’s American vision naturally directs the gaze eastward across the Pacific Ocean, while the TT, with Hong Kong as a starting point, reorients the gaze westward and then back to Asia. The redirection renders the omission of China logical within the TT framework. Nonetheless, the geographical mention of “China” is once again excluded in CP.

Within the framework of the Cold War cultural diplomacy, the systemic exclusion of “China” in CP’s translations, if analyzed without a differentiated approach to the 1970s local context, could easily be perceived as a result of the Asia Foundation’s funding, for the American patronage would work through the “ideological component” on translation (Lefevere 1992/2017, p. 13). One might assume that the Union, aligning with the state interests, would preferentially highlight the presence of Western bloc countries while omitting any representation of communist ones. However, such an assumption becomes questionable when considering the notable inclusion of the Soviet Union in various translated content in CP. In stark contrast to the omission of the China episode, the series of Gulliver’s adventure includes a translation of his travel to the Soviet Union, wherein Gulliver joins a Russian ballet troupe and, with the candid assistance of the chief director and other performers, achieves a spectacular performance (CP tr 1976, pp. 16–17). The relatively positive portrayal of the Soviet Union reminds us of the potential “counter-productive” effect, which can run contrary to what state powers intend in the execution of a nation’s cultural diplomacy (Otmazgin 2012, p. 38; Jiang 2021, p. 896). After all, the US would not typically endorse a positive image of the Soviet Union, especially during the 1970s. The Soviet Union is also included in an episode of the Doraemon series. When the protagonist, the Japanese boy Nobita expresses a desire to become an astronaut in hope of reaching Mars, his companion, the robotic cat Doraemon, comments in the ST, “America or the Soviet Union will probably achieve it first” (“アメリカかソ連が先にいっちゃうだろ” in Japanese) (Fujio 1978/1985, p. 76). This commentary, which lightly parodies the Cold War’s rivalry between the two superpowers, is preserved in the TT “美國或蘇聯會先成功吧” (CP tr 1978, p. 26), thus including the presentation of the communist Soviet Union.

Given that CP did not avoid depicting communist countries, the specific exclusion of China seems to be motivated by the Union’s China-centric agendas of constructing “a democratic China” rooted in authentic Chinese legacies (Lin 2018, p. 33). This envisioned notion of China sharply contrasts with the PRC founded by the CPC, wherein the exotic communism is perceived as a force eroding genuine Chinese customs and ethics (Fu 2019b, p. 76). By omitting the geographical term “China”, CP takes a firm stance against its political implications. This sentiment was likely intensified in the 1970s when the CPC-initiated Cultural Revolution was pervasively uprooting historical Chinese values on the Chinese mainland, whilst the PRC gained international recognition as “the only legitimate representative of China to the United Nations” in 1971.Footnote 5 It is plausible that the Union fervently resisted any possible association with it, leading to the complete omission of its geographical references. At the same time, while the Union members maintained friendly ties with intellectuals in Taiwan, it paradoxically disapproved of the KMT-ruled ROC (Lo and Hung 2014, p. 62, p. 148), criticizing its “autocratic governance” and “political mismanagement” (Fu 2019b, p. 77). So, the absence of “China” also signifies an intentional distancing from the ROC and the political fallacies it carries. This dual exclusion of “China”, as also documented in CP’s original Chinese stories (Wang 2016, pp. 113–114), articulates the Union’s vision of an idealized China, free from communist ideology and autocratic tendencies. The tactical deployment of omission and substitution in the TTs is derived from the deliberate intent to distance itself from the contemporary political entities that fell short of the Union’s expectations.

Promotion of the cultural and historical “China”

Although “China”, in its political and geographic sense, was excluded from CP, an emphasis on promoting a cultural and historical “China” was placed in its Chinese renditions. The STs have been extensively domesticated, by a replacement of original verbal and visual elements with those conspicuously reflective of traditional Chinese culture. Two episodes, one from Gulliver’s adventure and the other from Doraemon, are discussed, to illustrate how their TTs in CP champion the culturally affluent and historically momentous China as an inclusive civilization, which essentializes the Union’s China-centric agendas.

In the episode of “Gulliver Guinea-Pig Saves Summer”, where Gulliver travels into a fairyland and combats bad weather, the characters’ names and their living places were domesticated in the TT, anchoring the ST in a Chinese mythological and folkloric context. In the ST, the evil “Jack Frost” of the “Ice Palace” spreads winter’s chill, while the kind-hearted “Summer Queen” from the “Golden Palace” fights for warmth and hope (Roberts 1961a). In the TT, these figures were renamed “Frost Spirit” (“霜精” in Chinese) and “Spring Goddess” (“春天女神” in Chinese), residing in the “North Pole Ice Palace” (“北極冰宮” in Chinese) and “Golden Hall” (“黃金殿” in Chinese), respectively (CP tr 1975a, pp. 16–17). The “Frost Spirit” follows the Chinese folklore tradition of associating spirits with natural phenomena and making them mirror the behavior of their corresponding elements. The term positions “Jack Frost”, the European-originated personification of frost and coldness in the ST, as one of these elemental symbols in Chinese tales that personifies the natural force of frost. The Chinese mythological association was even intensified in “North Pole Ice Palace”, Jack Frost’s residence in the TT, given that in Chinese mythology, the northernmost realm symbolizes a distant and isolated abode, thus revealing his remoteness and the cold nature of his character. In the same vein, the use of “Goddess” in the TT situates “Summer Queen” among the female deities of Chinese mythology, who, usually beyond the earthly world, are called upon for protection and blessings. Compared to a literal translation of “Summer” (“夏天” in Chinese), “Spring” (“春天” in Chinese) seems more commonly associated with rebirth and renewal in Chinese culture, to emphasize Summer Queen’s countermeasure against Jack Frost. Lastly, “Golden Hall” evokes imagery of grand imperial Chinese architecture, adorned with golden roofs and wall-carvings. It signifies the high status of the “Spring Goddess” in the TT, who contains the power of Jack Frost and dispels wind and fog.

In effect, the above CP’s domestication successfully transforms a foreign narrative into the form of Chinese myths and folklore. The translated product could forge “an emotional dimension with which people can identity” (cited in Von Flotow 2018, p. 195) among the targeted Chinese audience in Hong Kong. It speaks of the Union’s conscientious efforts to provide young readers with a window into, and an appreciation for, Chinese cultural heritage. The cultural and historical promotion of “China” by CP penetrates the STs through its strategy of domesticated translating, or “sinicization” in its own terms (Lo and Hung 2017, p. 200). This practice was intriguingly exemplified when the closely related Japanese culture was involved in the Doraemon Series of the 550th issue. In the ST (Fujio 1974/1997a, p. 99), the protagonist Nobita traces his lineage back to Japan’s “Sengoku period” (“戦国時代” in Japanese, 1467–1615), a term itself borrowed from China’s historical “Warring States Period” (“戰國時代” in Chinese, 475 BCE to 221 BCE), metaphorically indicating a time of disorder and chaos. Despite the evident shared origins and meanings in the ST, the TT adopted the “Warring States Period” as its timeframe (CP tr 1975b, p. 25). Additionally, designations within the corresponding Japanese social hierarchy were domesticated to fit the Chinese feudal context of that era: a high-ranking lord and a chief retainer (“とのさま” and “家老” in Japanese) from the ST (Fujio 1974/1997a, pp. 110–111) are rendered into their Chinese equivalents in the TT (“諸侯” and “封相” in Chinese) (CP tr 1975b, pp. 32–33), which accurately reflect official titles during the Warring States period in ancient China. To further ensure visual cultural authenticity in the TT, the Japanese warrior, originally depicted with horn-like ornaments on a kabuto helmet, was altered to wear a red decorative tassel attached atop military headgear (CP tr 1975b, p. 30), a symbol of victory in Chinese belief.

As discussed above, CP’s domestication effectively eliminates the foreign “cultural other” in the ST (Venuti, 1995/2008, p. 264), be it the English exoticism or the subtle nuances found in Japanese texts. This translation method, inherently “ethnocentric” (Venuti, 1995/2008, p. 16), superiorizes the rich Chinese cultural and historical heritage in the receiving Chinese-language readership. The TTs function as a retelling or rewriting of China’s past glories and achievements, making them “fresh, relevant, and appealing to younger audiences” (cited in Von Flotow 2018, p. 195). CP’s attempt to familiarize traditional Chinese culture among younger generations may still be seen as collaborative with American anti-communist cultural diplomacy, since Shen suggests that the potential “defeat by communism” threatens the Union’s mission of “revival of Chinese tradition” (2017, p. 603). However, considering the non-linear communication process of the state’s intended message to the addressee, often “through several built-in layers of mediation” (Shen 2017, pp. 602–603), the CP’s cultural practice of translations should be viewed more as ready responses to local concerns. The Chinese Civil War between the CPC and KMT divided the Chinese nation both physically and ideologically, compelling a once-united Chinese ethnicity into diasporic dispersion and exile. For the Third Force groups like the Union, the diaspora of the Chinese people threatened China as a formidable nationalist power.Footnote 6 In this crisis, a communal feeling or a homogeneous identity within the broad framework of Chinese civilization – a depoliticalized conceptualization from a cultural and historical dimension of China – came to the Union’s rescue of the nation. This umbrella term could be as inclusive as it differs from the present disappointment and disillusion. It could involve the legendary tales and the nostalgia for ancient times, as seen in the aforementioned translation cases, as well as the literary canon of the “Four Chinese Classical Novels” and the aesthetics of Chinese calligraphy, as observed in CP’s original content by Fok (2011). Chinese civilization is perceived as “the intrinsic roots” of communal identity and a source of comfort for individuals of Chinese descent who share ancestral ties (Fu 2019b, p. 76), thereby uniting Chinese communities regardless of their ideologies and whereabouts. In this sense, CP’s promotion of Chinese culture and history would likely generate cultural impacts beyond the intentions of state power whilst being “greatly valued in the colonial Hong Kong” (Lo and Hung 2017, p. 24). It fulfills the capacity of the Union’s local resistance against British colonialization, crucial in reinforcing the awareness and remembrance of Chinese heritage among the youth, which risked being eclipsed under colonial rule.

Adaptation for Hong Kong consciousness

In parallel to the discernible patterns of exclusion and promotion vis-à-vis China in the translations within CP, the adaptation of STs for the Hong Kong consciousness emerges as a third characteristic. The analysis finds that the TTs actively addressed public concerns and tapped into civic life through an array of additions and substitutions wherever textually possible and suitable. Unlike the previous two features, which fully exercise Union’s China-centric agendas, this one reflects a realistic and negotiated move, signifying the localization of the CP’s cultural practice in response to the evolving Cold War landscape in the 1970s Hong Kong.

In the Doraemon series of the 541st issue, Nobita is accused by his friend Takeshi of discarding gum on the ground. As shown in Table 2, the dialogue from the ST to TT remains largely unchanged, but the TT includes an addition of “the Clean Hong Kong Campaign” in Takeshi’s critique of Nobita’s wrongdoing. This public initiative, launched by the British colonial government in 1972 to improve cleanliness in the city, had become an integral part of life in Hong Kong by the time the TT was published in 1975. By incorporating it into the TT’s hygiene-themed conversation, CP established a positive interaction with the civic sensibilities of the local populace. Other than that, this engagement reflects a localized cultural practice if we take the role of the British colonial government in the 1970s Cold War era into account. While the US deployed cultural diplomacy in Hong Kong, the British administration long kept a distance from American anti-communism efforts, avoiding actions that might “antagonize” the CPC (Roberts 2016, p. 45). Entering the 1970s, however, the British colonizer had to take the initiative to safeguard its governance over Hong Kong. This necessity arose as America softened its stance toward the CPC, seeking leverage against the Soviet Union, while the 1967 anti-government riots, fueled by communist left-wing ideologies, swept through Hong Kong, eliciting perceptible threats to British rule. The “Keep Hong Kong Clean Campaign” was part of these reforms, aimed at constructing public confidence in and recognition of the colonial government’s leadership (Lui 2012/2023, p. 128). These policies, which improved civic well-being, fostered a sense of Hong Kong identity and belonging (Cheung 2017, pp. 170–171). As a result, the newly emerging local consciousness underpinned a novel landscape for Cold War cultural diplomacy in Hong Kong. Failing to react to this shift, the Union’s periodicals like the Chinese Student Weekly lost touch with the Hong Kong people and ultimately ceased publication. In contrast, CP astutely adapted its content to resonate with this change, as is evidenced by the addition of the clean-up campaign to its translated narrative. From a pragmatic perspective, the adaptation was likely also a calculated decision by CP to remain in print and continue its cultural engagement with Hong Kong.

As the dialogue in Table 2 proceeds, with Nobita being asked to clean up Takeshi’s room as punishment, another delicate difference is noted: “Japan” in the ST is replaced with “Hong Kong” in the TT. This substitution of locale is not an isolated instance but part of a systematic adaptation strategy employed throughout CP’s TTs. In the Doraemon series, verbal references to Japan are constantly changed to Hong Kong (as seen in Issues 541, 558, 561, 567), and visual displays, such as maps of Japan, are replaced with corresponding images of Hong Kong (as seen in Issues 546 and 596). Similarly, regadring Gulliver’s adventure as a reporter, whereas in the ST he travels to “the seaside” in “London” (Roberts 1961b), in the TT he is adapted to go to the most well-known “Repulse Bay” (“淺水灣” in Chinese) in “Hong Kong” (CP tr 1974, p. 16), rather than any unspecified seaside. By presenting familiar locations to Hong Kong readers, CP strengthens their lived experiences, where a physical and psychological feeling of belonging is attached to Hong Kong as their genuine home. Hence, it is a translation choice driven by the concern of the rising local consciousness. At the same time, this strategy is also motivated by the Union’s agendas regarding China: since “China” has to be excluded in its geographical sense, which rules out both the Chinese mainland and Taiwan as real settings, Hong Kong is left as the singular applicable locale to contextualize Chinese translations.

The translation, adapted for Hong Kong consciousness, also actively addressed its readership’s linguistic need by naming original characters from the STs in Cantonese, as illustrated in Table 3. In the 1970s Hong Kong, CP’s choice of Cantonese resulted from the new conditions under British rule. Before 1967, the city was a mosaic of Chinese dialects, reflecting the diverse origins of its residents, with Cantonese, Hokkien, Hakka, Shanghainese, and Mandarin, being spoken. In the aftermath of the 1967 disturbances, however, the colonial government restricted the use of Mandarin, viewing it as a vehicle for leftist ideology and sentiments sympathetic to the CPC. The public usage of other non-Cantonese dialects was also curtailed, leading to a Cantonese-dominant linguistic milieu (Lau 2005, p. 25). Consequently, CP had to accommodate a readership of youth increasingly proficient in Cantonese by the 1970s, to ensure persistent involvement with local readers. Yet, CP’s adaptations never gave up on the Union’s goal of promoting Chinese culture, for they embedded Chinese cultural connotations within Cantonese dialectal forms in the TTs.

For instance, in Gulliver’s adventure as a reporter (Roberts 1961b), Johnny Smith, the boy who saves Gulliver’s career, is renamed “Ah-Man” in the TT (CP tr 1974, p. 17). The prefix of “Ah” shows familiarity and affection in Cantonese names, while the deliberate selection of “Man” bears a wider Chinese cultural symbolism of sharpness and quickness, to commend Johnny’s keen instinct in capturing pivotal photos. Such naming practice of integrating Chinese cultural connotations into a Cantonese form is extensively adopted in the Doraemon series. The poor beggar “Mr. Abara Tani” (meaning Mr. Shabby House in Japanese) is translated as “Ah-Cou”, where “Cou” (grass) in Chinese connotes poverty due to its unstable foundation. Apart from the affix, Cantonese suffixes are used in the same fashion. The translation “Naughty boy” adapts the Japanese name of a trickster from the ST. “Naughty” (“頑皮” in Chinese) is associated with slight disobedience in Chinese culture, and when combined with the intimate Cantonese suffix “boy” (“仔” in Chinese), it evokes a vivid image of a mischievous but endearing kid. Similarly, the Japanese “Noroma” is adapted to “Ah-slow Brother” in the TT, merging the Chinese notion of slowness with an ironic tone delivered through the Cantonese suffix “Brother”, capturing Nobita’s hesitancy while lightening the tease in idiomatic Cantonese. CP’s translations, adapted for the Cantonese medium, accorded with British interests by adopting a dialect divergent from Mandarin and its associated leftist revolutionary politics in the Chinese mainland. While the intentional choice solidified the British-favored language as Hong Kong’s de facto lingua franca by the 1970s, CP’s selection of given names imbued with Chinese cultural connotations underscores its unwavering commitment to the Union’s China-centric agendas. It offered young readers access to the communal Chinese civilization, acting as an indirect countermeasure to the colonizer’s efforts to dissociate the people of Hong Kong from their Chinese roots.

Conclusion

During the Cold War, as China underwent tumultuous changes, the Union relocated to Hong Kong and sought a path different from that of the Nationalists and the Communists. With a shared political conviction, it became a non-official collaborator in the network of American cultural diplomacy, but simultaneously furthered its China-centric agendas through publications. This study, by meticulous examination of translations featured in its child-oriented magazine CP, analyzes how they were configured to achieve the Union’s overarching objectives. The exclusion of “China” – a geographical detachment from the Chinese mainland and Taiwan – stems from the Union’s critique of the political orientations of the CPC and ROC. Meanwhile, promoting “China” from a cultural and historical dimension supports the belief of Chinese civilization as a unifying foundation for the nation that the Union genuinely treasures. Situated in 1970s Hong Kong with a surge of local consciousness, CP opted for pragmatic adaptations to remain in touch with its readership. This move guaranteed the viability of its publication, and strategically attended to the Union’s ultimate concern with China.

Emphasizing the Union’s role enhances our understanding of CP in a differentiated approach, moving beyond “the preventable biased insights from the perspective of patronage” on US-associated cultural products (Du 2022, p. 140). American cultural diplomacy, providing funding and resources, enables multi-natured agencies to engage in cultural activities, particularly in the realm of inter-language communication via translation methods and strategies. These transnational practices, carried out in a complex layered structure from the highest levels of power to area-specific contexts, open up manifold possibilities for interpretations in future scholarly work, not only through an agency-focused approach but also from a localized perspective. Operating in British-ruled Hong Kong, the Union’s publication had to navigate social-political challenges, exacerbated by the increasing visibility of the British by the 1970s. CP’s diplomatic translation initiatives, reiterating Chinese heritage as subtle resistance to colonization, produced cultural outcomes extending beyond objectives purported by the state authorities. As the most longstanding and reputable children’s magazine, CP established a strong bond with its local readership through translations, leaving a lasting legacy on Hong Kong’s youth that went beyond Cold War polarities. It never wavered in the Union’s relentless pursuit of a progressive nation, serving as a microcosm of the Chinese people in China’s journey forward.

Data availability

The result of the factual survey in this study is available from the author on reasonable request.

Notes

The “Third Force” (第三勢力) refers to minor political parties, intellectuals and powerful entities opposing the CPC and KMT in the Chinese Civil War (1945–1949). They sought a distinct third path to develop a modern democratic China (see more in Fu 2019a, pp. 49–52).

HK-based Chinese writers Chip Tsao, Yishu, and ordinary readers commented favorably on CP’s translated stories. See the link below (Accessed 20 January 2024). https://www.hk01.com/article/86746?utm_source=01articlecopy&utm_medium=referral

CP’s inaugural editor-in-chief, Yan Qibai, had his early upbringing in Lvshun, a city under Japanese colonization. Fluent in Japanese, he acknowledged the high quality of Japanese children’s magazines. Building upon his insights, CP continued to use Japanese publications as benchmarks for children’s education (Lo and Hung 2017, p. 196).

See Resolution 2758 during the 26th Session of the United Nations General Assembly. Refer to the link below (Accessed 20 January 2024). https://ask.un.org/faq/320138

See more in Tang Junyi’s article “On the Dispersion of the Chinese Nation” (說中華民族之花果飄零), included in his book titled “On the Dispersion of the Chinese Nation”, published by Sanmin Press, Taipei, in 2005.

References

Cheung K-W (2017) How the 1967 riots changed Hong Kong’s political landscape, with the repercussions still felt today. In: Ng H and Wong D (eds) Civil unrest and governance in Hong Kong: Law and order from historical and cultural perspectives. Routledge, London, pp. 156–184

CP (tr) (1971) Xiong baobao熊寶寶 (Baby bear). Children’s Paradise (453): 4–9

CP (tr) (1973) Dou chuiniu鬥吹牛 (Bragging competition). Children’s Paradise (497): 22–25

CP (tr) (1974) Tuboshu dang jizhe土撥鼠當記者 (Gulliver as reporter). Children’s Paradise (523): 16–17

CP (tr) (1975a) Tuboshu jiu chuntian土撥鼠救春天 (Gulliver saves summer). Children’s Paradise (539): 16–17

CP (tr) (1975b) Zuxian bu zhengqi祖先不爭氣 (Hopeless ancestors). Children’s Paradise (550): 24–33

CP (tr) (1975c) Zaofeng ji造風機 (Typhoon machine). Children’s Paradise (541): 28–32

CP (tr) (1976) Tuboshu tiao baleiwu土撥鼠跳芭蕾舞 (Gulliver dances ballet). Children’s Paradise (559): 16–17

CP (tr) (1978) Kongzhi zhongli ji控制重力機 (Gravity-controlling machine). Children’s Paradise (619): 26–32

Du Y (2022) When American Cold War modernism met Chinese Cultural Nationalism: Revisiting modern literature and Art Association Hong Kong and its remaking movement of Chinese culture. Comp Lit Chin 3:139–160

Dr. Seuss (1958) The big brag. In Yertle the turtle and other stories. Random House, New York, pp. 30–45

Fu P-S (2019a) Cultural Cold War in Hong Kong: The Chinese Student Weekly and the Asia Foundation I. Twenty-First Century 3:47–62

Fu P-S (2019b) Cultural Cold War in Hong Kong: The Chinese Student Weekly and the Asia Foundation II. Twenty-First Century 4:67–82

Fujio F (1974/1997a) ご先祖さまがんばれ (Ancestors, do your best). Inドラえもん (Doraemon), vol 1. Shogakukan, Tokyo, pp. 96–111

Fujio F (1974/1997b) 台風発生機 (Typhoon generator). Inドラえもん (Doraemon), vol 14. Shogakukan, Tokyo, pp. 69–76

Fujio F (1978/1985) 野比家が无重力 (The Nobi family has zero gravity). Inドラえもん (Doraemon), vol 32. Shogakukan, Tokyo, pp. 74–85

Fok Y-Y (2010) Considerations and impact of translation: Western children’s picture books in Children’s Paradise. In: Fang W (ed) Chinese Children’s Culture. Zhejiang Juvenile & Children’s Publishing House, Hangzhou, pp. 238–245

Fok Y-Y (2011) Image reconstruction: The transformation of picture books in Hong Kong’s Children’s Paradise. In: Fang W (ed) Chinese Children’s Culture. Zhejiang Juvenile & Children’s Publishing House, Hangzhou, pp. 142–164

Jiang M (2021) Translation as cultural diplomacy: a Chinese perspective. Int J Cultural Policy 27(7):892–904

Lau C-F (2005) A Dialect Murders Another Dialect: The Case of Hakka in Hong Kong. Int J Sociol Lang 173:23–35

Lefevere A (1992) Translation, rewriting, and the manipulation of literary fame. Routledge, London & New York, /2017

Li B (2013) USIS-commissioned translations in Hong Kong in the 1950s: A case study of Mae Soong’s Chinese translations of American literature. East J Transl 3:13–21

Li B (2022) USIS-funded literary translation in Hong Kong in the Cultural Cold War: a study of literary translations in World Today (1949–1952). Perspectives 30(6):941–956

Lin S-C (2018) The study of Qiong Yao’s text in Hong Kong Union Press Publication (1950–1970). Dissertation, National Tsing Hua University

Lo W-L, Hung C-K (eds) (2014) Voices on Hong Kong Culture I. Joint Publishing HK, Hong Kong

Lo W-L, Hung C-K (eds) (2017). Voices on Hong Kong Culture II. Joint Publishing HK, Hong Kong

Lui T-L (2012/2023) The Familiar 1970s. Chung Hwa Book, Hong Kong

Lygo E (2018) Translation and the Cold War. In: Evans J and Fernandez F (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Politics. Routledge, London, pp. 442–454

Minarik E (1957/1985) Little bear’s wish. In Little Bear. HarperCollins, New York, pp. 50–63

Otmazgin N (2012) Geopolitics and soft power: Japan’s cultural policy and cultural diplomacy in Asia. Asia-Pac Rev 19(1):37–61

Popa I (2018) Translation and communism in Eastern Europe. In: Evans J, Fernandez F eds The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Politics. Routledge, London, p 424–441

Roberts D (1961a) Gulliver Guinea-Pig Saves Summer. In Playhour 4-1 (no original page number)

Roberts D (1961b) Gulliver Guinea-Pig the odd job–reporter. In Playhour 4-15 (no original page number)

Roberts P (2016) Cold War Hong Kong: Juggling opposing forces and identities. In Roberts P and Carroll JM (eds) Hong Kong in the Cold War. Hong Kong University Press, Hong Kong, pp. 26–59

Shen S (2017) Empire of information: The Asia Foundation’s network and Chinese-language cultural production in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. Am Q 69(3):589–610

Venuti L (1995/2008) The translator’s invisibility: A history of translation. Routledge, London & New York

Von Flotow L (2018) Translation and Cultural Diplomacy. In: Evans J and Fernandez F (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Politics. Routledge, London, pp. 193–203

Wang J (1998) A review of the “green-spine culture” thought in Hong Kong. Guangdong Soc Sci 2:87–91

Wang M (2020) Eileen Chang, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and the politics of Cold War translation. Amerasia- J 46(3):330–345

Wang M-H (2014) Translating Taiwan literature into foreign languages in the Cold War era: The operation of USIS book translation program (1952–1962). J Taiwan Lit Stud 19:223–254

Wang M-H (2022) Transnational non-communist strategies and American cultural propaganda in the Cold War period: On Asia Foundation in Thailand (1954–1963). EurAmerica 52(4):567–611

Wang N (2016) Children on the “battlefield”: A comparative study of Hong Kong children’s magazines Illustrated Magazine for the Young and Children’s Paradise (1963–1967). In: Xu L and Li L (eds) Constructing Nanyang children: Studies on children’s periodicals in Chinese and culture in post-war Singapore and Malaysia. Global Publishing, Singapore, pp. 101–120

Zhao X (2017) Nationalism and colonialism: The paradoxical thought of the Union and the Chinese Student Weekly. Soc Sci J 4:165–171

Zhao X (2018) The “overseas” continuation of modern Chinese literature: Hong Kong literature in the framework of the Cold War. North Forum 1:25–32

Acknowledgements

This paper is funded by the 2021 Guangdong Provincial Social Science Scheme (Grant number: GD21WZX01-04) and the 2021 Guangdong Provincial Educational Science Scheme (Grant number: 2021GXJK078).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xueyi Li is the sole author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X. Translations in Children’s Paradise (1970–1979): the Union’s agendas and the Cold War cultural diplomacy in Hong Kong. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 421 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02927-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02927-4