Abstract

Through social media like Instagram, users are constantly exposed to “perfect” lives and thin-ideal bodies. Research in this field has predominantly focused on the time youth spend on Instagram and the effects on their body image, oftentimes uncovering negative effects. Little research has been done on the root of the influence: the consumed content itself. Hence, this study aims to qualitatively uncover the types of content that trigger youths’ body image. Using a diary study, 28 youth (Mage = 21.86; 79% female) reported 140 influential body image Instagram posts over five days, uncovering trigger points and providing their motivations, emotions, and impacts on body image. Based on these posts, four content categories were distinguished: Thin Ideal, Body Positivity, Fitness, and Lifestyle. These different content types seemed to trigger different emotions regarding body image, and gender distinctions in content could be noticed. The study increased youths’ awareness of Instagram’s influence on their mood and body perception. The findings imply that the discussion about the effects of social media on body image should be nuanced, taking into account different types of content and users. Using this information, future interventions could focus on the conscious use of social media rather than merely limiting its use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the present age, social media is a day-to-day companion for many. Checking social media posts at the beginning and end of each day is an integral part of daily routines among our society, especially among youth. Close to all youth (we refer to adolescents and young adults between 18 and 25 years of age with the term ‘youth’, following convincing arguments of an extended period of adolescence; Arnett et al., 2014; Sawyer et al., 2018) have a smartphone and thereby the possibility to access social media platforms (Vogels et al., 2022). As young people are oftentimes in almost daily contact with social media, they are not simply platforms where people share highlights of their lives, but they are also outlets for identity creation (Pouwels et al., 2021). The content shown on these social media are powerful transmitters of societal standards, beliefs, and values, which lead to certain societal ideals. These ideals, including weight, beauty, fashion, gender, food, and fitness, have an impact on one’s body image (Burnette et al., 2017). Body image is referred to as “the picture of our own body which we form in our mind, that is to say, the way in which the body appears to ourselves” (Schilder, 1950, p. 11). It is about how someone treats, feels toward, and thinks about their body (Tylka, 2011).

On social media platforms, individuals can be exposed to a variety of content, including images of individuals and bodies that are nearly “perfect” (Perloff, 2014). It has been found that the internalization of these “perfect” thin body ideals leads back to the pressure of cultural and social forces, including the urge to fulfill socially defined ideals of beauty and physical appearance and the desire to fit in (Perloff, 2014). The constant exposure to these “perfect” images might affect how young people view themselves and their bodies (e.g., Franchina and Lo Coco, 2018; Yang et al., 2020). Statistics show that around 20–40% of young adolescent girls report being unhappy with their bodies (Ben Ayed et al., 2019; Bucchianeri et al., 2013; Kearney‐Cooke and Tieger, 2015; McLean et al., 2022; Ricciardelli and McCabe, 2001). Additionally, it seems that the percentage of body image dissatisfaction increases throughout late adolescence and young adulthood (Bucchianeri et al., 2013; Kearney‐Cooke and Tieger, 2015; Quick et al., 2013). Body image concerns are not only observed among girls, as research showed that 20–30% of adolescent boys feel upset with their bodies (McLean et al., 2022; Schuck et al., 2018; Quick et al., 2013).

Previous scholars have assessed the influence of social media on body image, often in a quantitative way (e.g., Ahadzadeh et al., 2017; Brewster et al., 2019; Sebre and Miltuze, 2021). These studies have shown that a longer duration of social media use is related to a more negative body image, which is oftentimes connected to a higher rate of social comparison as well (Abi-Jaoude et al., 2020; Fardouly et al., 2015; Perloff, 2014; Richards et al., 2015). To better understand the relationship between social media use, social comparison, and body image, additional correlational and experimental work has been conducted. For example, Di Gesto and colleagues (2022) have shown that exposure to likes on Instagram images increases body dissatisfaction, especially among women. Another study indicated that exposure to attractive celebrity and peer images can have detrimental effects on women’s body image (Brown and Tiggemann, 2016). Moreover, following appearance-focused accounts on Instagram (Cohen et al., 2017) and engaging in appearance comparison with fitspiration images (Rafati et al., 2021) were related to higher body dissatisfaction, thin-ideal internalization, body surveillance, and drive for thinness.

However, it is important to highlight that correlational and experimental studies often focus on the impact of a one-time exposure to Instagram pictures, which may not fully capture the nuances of individuals’ everyday and moment-to-moment experiences (Slater et al., 2017). Little work has been done to comprehend the connection between the exact content youth are exposed to on social media and their body image. Therefore, this study seeks to uncover characteristics of social media content that trigger body image qualitatively and across multiple time points across weekdays. More specifically, this study will focus on the Instagram posts youth identify to trigger their body image in relation to social comparison and positive or negative emotions.

Adolescence and young adulthood

Adolescence and young adulthood are a crucial time for developing one’s identity, the perspective of oneself, and health-related attitudes and behaviors (Arnett, 2007; Carrotte et al., 2015; Crone and Dahl, 2012). Identity development is a “process located in the core of an individual and yet also in the core of their social context” (Erikson, 1968, p. 22). In other words, young people are sculpting their identity based on internal processes, yet are also influenced by their context, including social media. In the present era, young people live in a hybrid reality that intricately connects digital and offline realms, making it increasingly difficult to disentangle ‘digital life’ from the contexts in which today’s youth navigate key developmental tasks (Davis and Weinstein, 2017; Granic et al., 2020). This not only challenges them to define themselves in their immediate offline environment but also to understand and form their identity, including these digital spaces. Social media platforms like Instagram offer vast opportunities for information access, exploration, and collaboration, supporting self-presentation and overall identity development (Sebre and Miltuze, 2021).

Body image can be defined as an integral part of our identity (Dittmar, 2009), given that it constitutes the subjective concept a person holds of their body as part of their self-representation (Dittmar, 2009; Halliwell and Dittmar, 2006). The representation of ourselves and of others (both in real life and on social media) can become risk factors for dysfunctional body image perceptions, especially during adolescence (Pellerone et al., 2017). For example, exposure to societal beauty standards on social media platforms can create significant gaps between their idealized identity presentation and their current self-beliefs. Feedback in the form of “likes” and “followers” from peers further influences their identity and self-esteem (Sebre and Miltuze, 2021). At this moment in time, identity development—and specifically the role of body image—in the digital age has not been researched in its full complexity (Dittmar, 2009; Granic et al., 2020).

Presenting ‘the self’ on social media

Spending time on social media means being exposed to the content of other users. A differentiation can be made between individuals presenting authentic aspects—their real selves— aspects they desire or wish to have—their ideal selves—or aspects that are not truthful—their false selves (Michikyan et al., 2014). One of the biggest criticisms towards current social media platforms is that they are designed to amplify performative aspects of personal storytelling and thereby cut back the opportunity for deeper interactions (e.g., Nesi et al., 2018). These performative aspects of social media might lead users to selectively choose to post idealized images of themselves (Manago et al., 2008), which might not represent their true and authentic selves and distort their sense of who they truly are (Ahadzadeh et al., 2017). Moreover, the use of digital manipulation (e.g., using Photoshop) heightens the exposure to content that lacks realism which in turn can lead to body dissatisfaction, eating concerns, and even cosmetic procedure attitudes or intentions (Beos et al., 2021; Lonergan et al., 2019; Wick and Keel, 2020). The presence of idealized images of people’s lives does not only impact the ‘poster’ of these images but can also influence other users encountering them, both passively (i.e., simply through scrolling, viewing, and monitoring of profiles) and actively (i.e., through liking, commenting, and posting; Bodroža et al., 2022; Thorisdottir et al., 2019; Verduyn et al., 2017).

Researchers exploring the varied effects of social media exposure on gender have observed notable gender differences. Casale and colleagues (2019) observed distinctions in the impact of exposure to same-sex attractive Instagram images on body image and dissatisfaction, with women experiencing increased dissatisfaction while men showed no significant effect. Moreover, women demonstrate higher levels of engagement on Instagram and are particularly more likely to engage in appearance-related comparisons than men, given their increased time spent on Instagram (Legkauskas and Kudlaitė, 2022; Twenge and Martin, 2020). An explanation for digital media having a more significant impact on the body image of females is deemed to be the tendency to self-objectify rooted in women’s nature (Fredrickson and Roberts, 1997). The idea of objectification offers a framework for comprehending the consequences of being a woman in a culture that sexualizes the bodies of women. This theory holds that objectification occurs when a woman’s body is valued separately from their identity. In turn, girls and women may internalize an external perspective on their physical appearance due to experiences of objectification (Feltman and Szymanski, 2017), contributing to gender differences in the effects of social media exposure.

Social comparison

A reasonable explanation of why social media has an impact on someone’s body image is the concept of social comparison. Foregoing research suggests that appearance-based social comparison is triggered by social media usage (Saiphoo and Vahedi, 2019). Psychologists have detected two primary motives for social comparison: self-evaluation and self-enhancement (Lewallen and Behm-Morawitz, 2016). Self-evaluation refers to maintaining a positive self-evaluation by comparing oneself to someone seen as inferior, which is done through downward comparison. On the other hand, self-enhancement is done to compare oneself to superior individuals for successful improvement, which is achieved by upward comparison (Lewallen and Behm-Morawitz, 2016). Overall, youth evaluate themselves by comparing themselves with the socio-cultural ideas presented in the media (Festinger, 1954). Fundamentally, this implies that comparing and exploring similar or dissimilar others helps them verify or deny aspects of their own identity, which they see as diagnostic and functional (Wood and Taylor, 1991).

Through social comparison, social media content can also have an impact on youths’ body image. Previous research has shown that social comparison on social media, especially in connection with thin-ideal imagery, is connected to overall increased body dissatisfaction (Aparicio-Martínez et al., 2019; Duan et al., 2022; Kleemans et al., 2016; Ralph‐Nearman and Filik, 2020). Additional research implies that especially passive social media usage is connected to greater depression symptoms, lower body image, and decreased well-being (Valkenburg et al., 2021; Verduyn et al., 2017). Studies have even found that the negative effects of social media on body image are a component that—in combination with other components—can lead to the development of eating pathologies (Abi-Jaoude et al., 2020; Brewster et al., 2019; Perloff, 2014; Richards et al., 2015; Stice and Shaw, 2002).

Thompson et al. (1999) created the tripartite influence model (TIM), a comprehensive framework to elucidate the origins and repercussions of thin idealization, particularly focusing on its antecedents and outcomes. According to the TIM, societal pressures promoting the idealization of thinness arise from three primary sources: family, peers, and the media. These external influences prompt individuals—mainly women—to engage in social comparison, wherein they assess their own bodies in relation to others, fostering a propensity to internalize the thin ideal as a standard of beauty (Donovan et al., 2020). As per the model, two primary mechanisms, the processes of appearance (social) comparison and thin-ideal internalization, contribute to a sense of dissatisfaction with one’s body (Keery et al., 2004). Consequently, this dissatisfaction is determined as the driving force of women pushing them to adopt unhealthy eating behaviors as they strive to achieve the perceived ideal of a thin body.

The potentially harmful effects of social media content on body image have not only been a topic of interest for researchers but have also been recognized by various groups of people in society. These people have chosen to act against these performative uses of social media by contributing towards a more positive attitude towards their body, embracing who they are, and stimulating body satisfaction. An example of this is the body positivity movement, which promotes body appreciation and diverse looks, shapes, sizes, and colors (Manning and Mulgrew, 2022). According to Tylka and Wood-Barcalow (2015), the body positivity concept is made up of six core elements. Namely, appreciation of the body’s uniqueness and functions, accepting one’s own body and loving it, and, in general, shifting from a narrowly defined concept of beauty to a broad one, investing in body care, inner positivity, and protecting oneself by forgetting negative body ideals. Body positivity posts on Instagram include enhancement-free pictures in which you can see body blemishes, cellulite, freckles, and stretch marks (Cohen et al., 2019). Research has shown that exposure to body-positive images improved the participants’ body satisfaction, body appreciation, and overall mood (Cohen et al., 2019; Williamson and Karazsia, 2018). These studies show that body-positivity content may offer a prosperous way to improve body image influences through social media.

Current study

Most studies have focused on the influence of social media use on body image, for instance, in relation to the duration of use or characteristics of the user, either in a correlational or experimental way (e.g., Ahadzadeh et al., 2017; Brewster et al., 2019; Brown and Tiggemann, 2016; Cohen et al., 2017; Di Gesto et al., 2022; Rafati et al., 2021; Sebre and Miltuze, 2021). The added value and novelty of the current study is that we provide a nuanced description of the type of Instagram content that triggers body image in relation to social comparison and positive or negative emotions. By means of a qualitative diary study we examine what type of content triggers youths’ body image, considering the nature of the content and how youth compare themselves with it. The chosen innovative methodology of a diary study provides day-to-day access to participants’ thoughts and emotions regarding the Instagram content they are exposed to. This approach enables an in-depth exploration of participants’ engagements and feelings at multiple time points in their natural environment (Carter and Mankoff, 2005; Chun, 2016; Gunthert and Wenze, 2012). We mainly focused on Instagram as it is currently one of the most popular social media platforms (Lister, 2022), and it primarily uses visually oriented content (Saiphoo and Vahedi, 2019).

Methodology

Participants

Our target sample size was 30 participants, as previous research has found that in more standard qualitative research (i.e., interviews), saturation was reached around 30 participants (Marshall et al., 2013). To be eligible for participation, participants had to be (1) frequent Instagram users (utilize the platform daily by logging in at least once a day); (2) between the ages of 18 and 25; and (3) able to read and write in English. In total, 33 participants were included in this study, of which 28 matched the inclusion criteria and completed at least 90% of the diary survey. Of the 28 participants, 6 (21%) identified as male and 22 (79%) as female. The mean age of all participants was 22 years (M = 21.86; SD = 1.33; range = 18–24). The sample consisted mainly of German participants (n = 19; 68%), a small group of Dutch participants (n = 5; 18%), and one participant from Spain (3.5%), Italy (3.5%), Bulgaria (3.5%), and India (3.5%) respectively. All participants were full-time students enrolled at a university.

Concerning participants’ Instagram usage, the vast majority (n = 13; 46.4%) used Instagram for 1–2 h a day. The three most given reasons that participants reported using Instagram were (1) to keep up with their friends (n = 27; 98%); (2) boredom (n = 15; 54%); and 3) to present themselves (n = 12; 44%). When asked which activities participants mostly performed on Instagram, all participants reported being active Instagram users, as 96% (n = 27) reported liking other Instagram posts regularly, 93% (n = 26) reported sending posts to their friends and engaging with them, 75% (n = 21) reported to save posts, and 64% (n = 18) reported that they commented on other posts frequently.

Procedure

In this study, we were mainly interested in how different Instagram content triggers body image and accompanying social comparison and positive or negative emotions in young people. We therefore chose to conduct a qualitative diary study in which we asked multiple open-ended questions at the end of the day. We made a conscious decision to only measure for five weekdays (no weekend days) and once a day, as we used open-ended questions that took quite a long time for participants to answer each day (between 10 and 20 min per day). We wanted to balance our need to collect day-to-day rich data around how different Instagram content triggers young peoples’ body image with participant study burden and preventing high attrition rates (Janssens et al., 2018). The study design and procedures were approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Behavioral, Management and Social Sciences of the University of Twente (approval number: 220799).

Participants were recruited through convenience and snowball sampling. To specifically target individuals who met the predetermined condition of being frequent Instagram users, recruitment efforts were conducted directly on Instagram. When individuals expressed interest in participation, comprehensive information about the study design and procedure was provided, and they had the opportunity to seek clarification and ask questions. Upon confirming their interest and understanding of the study, participants then proceeded to sign informed consent and initiated the 5-day diary study. In order to ensure smooth data collection, participants received a detailed WhatsApp message regarding the study and its procedure one day before data collection started. To further prevent possible misinterpretation, a detailed instruction form (see Supplementary Materials S1) was attached to that message. Before the start of the diary study, each participant received a private WhatsApp message at 10 a.m., which contained a link to a baseline questionnaire and their personal participation ID to pseudo-anonymize data once all data was collected. At 6 p.m., every participant received another message reminding them to fill in the baseline questionnaire. This baseline questionnaire was used to gain a better understanding of the study sample and its demographics, such as motivation for Instagram usage. The day after the diary study started. Again, participants received the diary study link and their participation ID at 10 a.m. via WhatsApp, followed by a reminder message at 6 p.m.

Instruments

In the diary study, participants were asked to identify one post each day that influenced, triggered, or stimulated them to think about their body image. We specifically prompted them to “Identify and screenshot one post which you came across on Instagram which made you think about your body image. This can be in a positive, neutral or negative way”. After determining that post and uploading its screenshot, a series of open-ended questions were posed. These questions concerned the exact reason for choosing that post, how participants came across this post, which activities they performed with it (e.g., liked, commented, shared), if they were related or knew the creator of the post, if they felt connected with the creator, and if the participants felt more, less, or equally attractive after seeing the post. Additionally, questions regarding the posts’ effects on participants’ body image were posed. We specifically asked participants to report how the post affected their body image (positively, neutral, or negatively), how big that impact was (on a scale from 1 = no impact to 10 = high impact), and how they felt after being exposed to the post and their thoughts throughout the process of seeing it (open question). In the last diary questionnaire on day 5, participants received some additional questions that asked them to evaluate their participation in this study and how that might have impacted their view on Instagram content and their body image. This inclusion of evaluative questions aimed to gain insights into the influence of the diary study on participants’ perceptions. Please note that our initial goal was to observe how participants experienced the diary study, but we unexpectedly found interesting additional insights that we, therefore, reported in the results section.

Data analysis

To ensure anonymity, all collected data was pseudo-anonymized (i.e., reported personal information was deleted). Furthermore, the data was transferred to an Excel Sheet and structured in an easily accessible way. The meaning, relevance, and value of responses were made clear by creating unique Excel sheets for each of the 28 participants based on all of their diary study responses. The data was analyzed by means of thematic analysis (Boeije, 2009). In the first round, we conducted a constant comparison method based on open coding by clustering and grouping images together. In the second round, themes were identified from the image clusters, which led to four labels: Thin Ideal, Body Positivity, Fitness, and Lifestyle, to which all selected content could be selected. Additionally, other characteristics in the picture, such as the number of persons, how the person was positioned in the picture, and the pictures showing naked or covered skin, were analyzed. Furthermore, the images were coded for other characteristics, such as the sender of the post and how the participants came across the post.

Then, participants’ underlying motives for selecting the content were analyzed by looking at their comments in which they explained why they selected the content. Five different motives could be distinguished, including feeling inspired, having a desire to look like that, being motivated to change one’s own body, feeling jealous, and feeling good about oneself. Additionally, we analyzed how the content triggered the body image among the participants. This was done by analyzing the type of comparison, i.e., upward or downward comparison, the emotions, and the general impact on body image that was triggered by the content. Finally, we connected participants’ demographic information to the coded content.

Based on these steps, a codebook was developed and used, existing of nine main codes, including: “Instagram post characteristics”, “Source/Sender”, “Content category”, “Instagram post selection motive”, “Instagram post trace”, “Body image impact”, “Triggered emotion”, “Social comparison”, and “Study impact”. The complete codebook can be found in Supplementary Materials S2.

Results

Over the course of 5 diary study days, a total of 140 Instagram post screenshots of 28 participants were collected. Based on these posts, four categories were distinguished, namely: Thin Ideal, Body Positivity, Fitness, and Lifestyle. Overall, it was noticeable that most of the participants showed a clear pattern of chosen content and oftentimes, a dominance of one specific category. Even though present dominance of one category, most participants also reported content belonging to other established categories. The specific reporting patterns of every participant, as well as demographic information and their average daily Instagram consumption time, can be found in Supplementary Materials S3. The majority of the selected content existed of posts created by people the participants did not know in person: most content was created by strangers, followed by celebrities, influencers, one’s social circle, brands, relatives, and other accounts (e.g., news pages and memes pages). Participants indicated that they came across the content by either following the creator, through Instagram’s suggestion and, to a lesser extent, through Instagram’s advertisements (see Table 1).

Content categories

Thin ideal

The type of content that forms the largest group is the Thin Ideal category and was purely selected by female participants (n = 53 Instagram posts; 21 participants). Thin ideal content includes pictures of individuals who fit in the socially created thin ideal. All selected Instagram posts displayed women who showed a lot of skin. Hereby, most of them wore bikinis, underwear, skin-tight dresses, athleisure, and see-through clothing. The Instagram posts were set in a scene with a focus on the creator’s body. The Thin Ideal content category contained a mixture of mirror pictures, close-ups of specific body parts, or full-body shots taken by other people. Figure 1 showcases such a thin ideal Instagram post showing a woman in a bikini. The participant (no. 10) explained her choice by stating: “This picture shows an overly perfect body type ideal.”

The motives for participants to select thin ideal content were that they either admired this body type, thereby expressing the wish to have such a body themselves or despised the body type and emphasized they were happy with their own body. Hereby, participants both engaged in upward and downward comparisons. Upward comparison mostly triggered negative emotions, creating a feeling of unhappiness, stress, or sadness. Different than the Fitness category below, this type of comparison did not lead to a motivation to become just like the person in the picture. For instance, one participant (no. 6) reported an Instagram picture of a thin ideal corresponding female wearing a tight long sleeve and a short skirt revealing her legs. She voiced the feeling that was triggered by the content: “I am a bit stressed, and also annoyed by all the perfectionism on Instagram. It makes me feel less pretty as I am not that “perfect” as the woman in the picture”. Other examples of such were addressed by Participant 4, who explained: “Imagine how nice life could be when you are that skinny”, and Participant 8, who voiced: “I want to have a body like hers and be able to wear that nice dress”.

Participants who were negative about the thin ideal regarded it as unhealthy or undesirable. Such downward comparisons were related to positive feelings in participants’ own bodies. Participant (no. 25) chose a post of a female showing a body transformation and said: “I’m happy that I do not look like the right version of the girl.” Likewise, another participant (no. 33) selected an Instagram post of a woman corresponding to the thin ideal and stated: “Actually I feel glad that my body is not as skinny as hers. I mean, she looks great, but I personally feel happy about my own body that it is healthy.” Other comments were, for instance: “She is really small and thin and underweight. This made me think about myself in a positive way and I am glad that I am healthy and not that thin” (participant no. 5), and “I feel pleased with my body because I see that everybody is unique, which makes it so special” (participant no. 2).

Body positivity

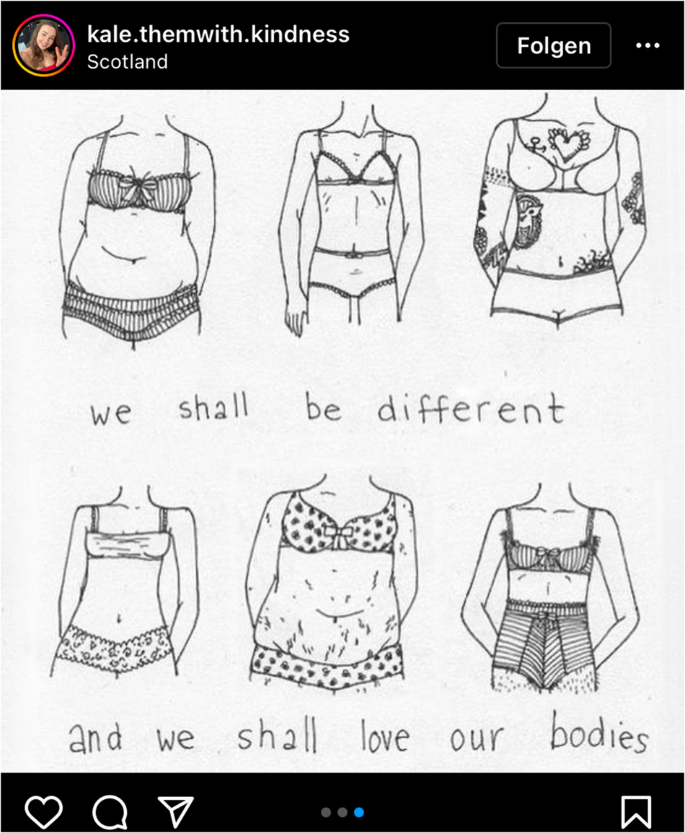

The second largest type of content relates to body positivity, which was again exclusively reported by female participants (n = 45 Instagram posts; 19 participants). A diverse set of posts belong to this category, referring both implicitly and explicitly to body positivity. For instance, participants selected pictures that displayed females who did not match the thin ideal, wearing bikinis or tight clothes. Also, candid pictures were selected, which are informal pictures captured without creating a posed appearance capturing the subject in moments that convey emotion and are honest and truthful. Additionally, posts that explicitly referred to body positivity were selected, such as illustrations and quotes showing that female bodies are beautiful no matter their size. An illustrative example of this category, selected by one of the participants (no. 28), is displayed in Fig. 2, which shows an image of different body types with the subscription ‘we shall be different, and we shall love our bodies’. The participant explained that it impacted her “Because it represents different bodies and shows that everybody is good the way it is” while further stating that “It does not matter how you look, your body is perfect, and you should love it”.

Participants had both societal and personal motives for selecting content related to body positivity. Societal motives were based on body positivity as criticism of current beauty standards that are advocated in advertisements or by social media influencers. One of the participants (no. 33), for instance, motivated her selection of a picture that showcases different breast sizes and forms with: “It made me think that society often still sexualizes women’s bodies and that this is not okay. This ad is a positive step into celebrating the diversity of our bodies.”, she further stated, “[…] This made me realize that we are all perfect, no matter how we look like, and that society takes a step forward in normalizing the female body.” Another participant (no. 14) shared this opinion and disclosed her discomfort about how unrealistic the beauty standards of society are, as “this can be hard for people who are unsure about themselves”.

Personal motives of participants included the relatability of the content as well as the reassurance of one’s own body image that was triggered by the selected content. For instance, one of the participants (no. 25) selected a picture of Lena Meyer Landrut (a German celebrity), who is lying on the couch without makeup on (i.e., a candid picture). She motivated her selection by: “It’s okay to have a bad day and to feel tired. We don’t have to be perfect or always good-looking.” Furthermore, a participant (no. 29) explained her selection of a bikini picture of a woman who does not meet the standards of the thin ideal through: “Even if you don’t have the flattest tummy, you can show yourself off. She [the woman in the picture] encouraged me that there is nothing to be ashamed of.”

All participants who selected body-positive content emphasized that they were positively influenced by it, and when a social comparison was indicated, this was mostly done in a downward way. An example of a positive emotion triggered by the selected Instagram post was addressed by participant no. 3: “I selected this post because it made me feel good and happy because although the post is not flattering at all, the woman seems so confident and happy”. Another example of triggering positive emotions is illustrated by the following quote: “The picture shows some natural stretches and lines. It made me realize that natural bodies don’t look perfect. It had a positive effect on my mood” (participant 20).

Fitness

The third category includes pictures related to fitness (n = 30 Instagram posts; 12 participants), which was selected by both men (24 posts) and women (6 posts). All screenshotted Instagram posts displayed the creators posting content in which they were posing for the camera showing off their muscles both with and without clothes or pictures of them working out in the gym. Figure 3, selected by participant no. 15, illustrates this category. He explained that this post motivated him to go to the gym.

Overall, all participants who selected content within this category engaged in upward social comparison, comparing themselves to someone who they thought was looking better than themselves. However, a clear contrasting gender differentiation concerning motivation to select this type of content and expressed triggered effects were brought to light. In the case of male participants, the reason was primarily because it motivated them to go to the gym and work on their bodies. All male participants belonging to the Fitness category reported being left motivated and inspired. As an example, participant no. 7 reported on his selection of an Instagram post in which a male is powerlifting: “Because it’s an example for myself to work hard on my body and to change myself for the better”. Similarly, participant no. 21 selected an Instagram post of a male posing in a gym presenting his upper body, to which the participant stated: “That is my goal physique, I have to work out harder [and I am] motivated to do more.” Moreover, participant no. 12, who selected an Instagram post in which a male is working out and showing off his arm muscles, stated: “It motivates me to see what the body is capable of doing”. Similarly, another participant (no. 15) screenshotted a post of a male in the gym highly demanding his upper body and expressed: “I felt motivated to push myself to the limit in the gym”.

On the other hand, female participants chose fitness content as a negative reminder that they should work on themselves more, specifically their body and fitness. In comparison to males, females engaging in upward social comparison were not left remotely uplifted, yet rather negatively triggered by this type of content. As an example, participant 9 chose the content of a female influencer who is posing in her workout outfit advocating to move one’s body and expressed being “disappointed in myself [..] of how long I haven’t trained anymore”. Comparably, another female participant (no. 17) chose a post of a female in the gym taking a mirror picture showing off her physique, to which the participant explained: “It made me think about how my progress would have been if I went to the gym more often.” It made her feel: “Sad because I could have been fitter now and I would have had a better routine with gym in my life”. Adding to the list, participant 6 chose a post from a female creator in a plank position and reported the post being “an explicit call to action” as “I am not sporty enough”. Likewise, another female participant (no. 14) chose to report a post in which a new workout video was advertised and stated that “I am doing not enough sports currently” and “That I should do more sport if I want to lose weight […]”.

Lifestyle

Different than the other categories, this last category concerns lifestyle posts (n = 12 Instagram posts; 6 participants). It was apparent that posts of the lifestyle category neglected physiques or other bodily aspects, thereby taking away upward or downward comparisons. More central in this category was how Instagram posts conveyed feelings and transmitted emotions. The focus of the reported Instagram pictures was primarily on the context in which the people were photographed, for instance, in a club, at a concert, out on the beach, what they are doing in the picture, or on the outfits people are wearing. Figure 4 shows an Instagram post of a singer on stage at a concert, which is illustrative for this category. The participant who selected this picture (no. 23) motivated this selection by: “I feel good that there is a scene where your body is not important; I don’t care about his body, just about his music”. As another example, participant 5 chose a picture of a person being photographed by a friend sitting in a chair with a wine glass in his hand and food on the table and said that he chose this post “because he is enjoying his life by sitting by the water and drinking wine and I would like to do that as well, it “makes me thinking of drinking with friends and having a good time”. Other posts belonging to the Lifestyle category concerns clothes and outfits. Participant 5, for instance, commented on a selected post of a girl with the motivation: “I liked her outfit and would want that too [..], I would like to shop now”. Similarly, participant 33 motivated her selection by: “I just really like her style” (participant 33).

Posts that belonged to the Lifestyle category mostly triggered neutral feelings towards one’s own body but elicited a positive overall mood. An illustrative comment on a selected picture of two celebrities taking a selfie holding each other in their arms was: “I think it made me feel good because I saw a great picture of two friends hanging out with each other. It didn’t really affect my mood about my body” (participant 7). Additionally, participant 9 chose a picture of her friend getting married and said, “It made me feel glad not to be married yet”.

Evaluations and realizations of participants

On the 5th and last diary study day, participants were asked to express their thoughts, feelings, and evaluations of this study. Out of all the collected answers, it was clear that participants were critical of the underlying mechanisms of Instagram, which, according to the participants, promote an ideal body image through the posted content and the algorithms of the platform. One of the participants (no. 2) stated: “[…] nobody is really representing themselves in a real and honest and transparent way”. Another participant (no. 24) commented “[…] Instagram only suggest good looking people and almost no normal bodies”, and participant 3 reported, “[…] it’s human to have problems. Some people don’t see that and could get serious problems because of how influencers share their perfect life”.

Participants also noticed the impact the platform had on their own moods and feelings: “There are so many pictures of influencers with perfect bodies and perfect skin. It’s crazy how many times I’ve thought to myself ‘I want to have this body´. It’s really unhealthy” (participant 26). One participant (no. 13) summarized it in an interesting way: “Most of the ads and influencers show the standard beauty standards. I knew that before, but when you start focusing on it, it is actually a bit sad. Generally, everything seems to be extreme. Either you are extremely perfect or extremely for body positivity. Nobody seems to be fine with just being themselves”.

It became apparent that after the diary study days, participants were more consciously in contact with their Instagram feed and their feelings. As an example, one participant (no. 10) said: “Automatically you compare yourself with other people you don’t even know. Sometimes that was motivating […]. But often, it made me also feel worse off about my own body, which is horrible, in my opinion. I think not seeing this kind of content too often is for sure healthier”. Moreover, it was stated that “[…] it really depends on if the person participating in this study is happy with their body or not. For me, I don’t really get affected by other people’s bodies, but people with low self-esteem can get affected by the amount of “perfect bodies” on social media” (participant 12).

Alongside expressing their thoughts on Instagram, participants also shared their opinions on the study, which were overall positive. For instance, one participant (no. 3) stated.: “I thought that it was a great idea because I got to know my body image better and […] it’s important to know and realize that you should take good care of your body”. Moreover, it was expressed that: “I got more conscious about what my body image really means to me and what type of pictures/bodies have an effect on me. […] I realized through this study that it definitely gets amplified through Instagram content, and I don’t believe it to be necessarily healthy” (participant no. 20). Similarly, another participant (no. 26) stated and learned to appreciate that: “I actually have been thinking these days about how much I actually love my body. It keeps me alive, and everybody has a different body”.

Discussion

The current study aimed to explore the dynamics between the content youth are exposed to on Instagram and their body image by means of a diary study. Research up until this point has mainly investigated this relationship quantitatively (e.g., Ahadzadeh et al., 2017; Brewster et al., 2019; Sebre and Miltuze, 2021) and has not delved deep into the complex relationship between being exposed to social media content and body image. Previous literature suggests that online social comparison leads to negative effects on body image and body dissatisfaction (Myers and Crowther, 2009; Eyal and Te’eni-Harari, 2013; Babaleye et al., 2020). The current study has shown that different established content categories, entailing Thin Ideal, Body Positivity, Fitness, and Lifestyle, triggered different responses with regard to youths’ body image.

The Thin Ideal body image category was most frequently selected, and only by female participants. They oftentimes reported negative thin ideal content in relation to upward social comparison, where participants compared their own body with the images displaying bodies or single body parts most esthetic and “perfect”. This thin ideal content made them feel bad as they perceived their own bodies as not corresponding with this content, leading to a negative body image and negative feelings towards one’s body. This type of content is often referred to in studies on the negative effects of social media use on body image (Aparicio-Martínez et al., 2019; Holland and Tiggemann, 2016; Qi and Cui, 2018). However, it also happened that the participants compared their bodies in a downward way with thin ideal content, emphasizing that they felt more comfortable in their own bodies than the bodies represented. Such instances triggered positive feelings regarding the participants’ own body image and can be construed as possible defense mechanisms to reduce the threat of a negative sense of self (Stapel and Schwinghammer, 2004; Wayment and O’Mara, 2008). The different effects correspond with previous studies that showed a connection between upward comparisons and negative emotions (Lewallen and Behm-Morawitz, 2016) and a neutralizing effect of downward comparison on body images (Tiggemann and Anderberg, 2019).

Body Positivity content was the second most often reported category and again only by women. Content-wise, this category showed completely opposite content compared to the Thin Ideal category. The body positivity movement has switched the focus from “picture-perfect” posts (thin ideal) towards natural candid pictures in which nothing seems to be staged overly “perfectly” (Manning and Mulgrew, 2022). Our results indicate that the message of this movement resonates among youth, as a group of female participants was relieved that society is moving away from the “perfect” thin ideal towards valuing and recognizing all types of bodies. Here, social comparison did not take place like in the Thin Ideal and Fitness categories; it was less judgmental and more of a supporting act. The participants cheered on the senders of the images for their fight against normalizing “imperfections”. Overall, the body positivity content triggered prominent positive emotions among female participants. This is in line with other research in this field (e.g., Cohen et al., 2019; Williamson and Karazsia, 2018) and illustrates the impact of the body positivity movement.

Different than the former two categories, the third category Fitness, was made up of mostly men. Instagram posts that dominate this content category are posts of very muscular and strong men, mostly in a gym working out or posing to show off their muscle gains. These images highly correspond to the societal ideal that men are supposed to be strong, fit and trained (cf., Franchina and Lo Coco, 2018; Frisén and Holmqvist, 2010; Parasecoli, 2005). Although male participants engaged in upward comparison with this content, it did not trigger negative emotions like in the Thin Ideal category with female youth. Instead, male participants regarded the images as inspiration and motivation to become a better version of themselves. An explanation could be that, in general, men have a more positive body image than women and thereby experience less negative social comparisons (MacNeill et al., 2017; Voges et al., 2019). An alternative explanation could be that the societal stereotype associated with males may contribute to a reduced expression of discomfort or vulnerabilities. Borinca et al. (2020) express that the differentiation between traits traditionally considered masculine and feminine is more significant for men than for women. The emphasis on such gender distinctions is particularly driven by men’s desire to distance themselves from traits associated with femininity, as it plays a crucial role in shaping their male gender identity.

The fourth category selected by both male and female youth, but less frequently than the previous three categories, is Lifestyle. This category stood out in the way that the content was not connected to extreme bodily looks and stereotypes: being overly skinny (Thin Ideal), overly “imperfect” (Body Positivity), or being extremely fit (Fitness). Instead, this category entailed images of people in a natural way and not staged, whereby the context mattered more than the people themselves. It appeared that participants selected this type of content to oppose against the focus on physical appearance on Instagram, thereby eliminating any upward or downward comparisons. Overall, such content did not trigger a predominant positive or negative feeling toward participants’ body image; it stayed neutral. However, stepping away from a bodily focus led to a comfortable feeling consisting of not being concerned about one’s body but rather solely feeling content as one is. This category shows that body image is more than feelings and thoughts about the physical aspects of one’s body (Tylka, 2011). Instead, societal dynamics and contextual elements, such as the environment or activities that are displayed in the image, play a role as well. Body image trigger points might not purely originate from others’ looks but may also arise from the contextual elements in which people are being displayed (Sarwer and Polonsky, 2016; Tylka, 2011).

While the categories themselves provided interesting insights, some overarching reflections allowed us to uncover additional insights. First, the results of this study indicate that body image is a gendered phenomenon as all female participants exclusively selected Instagram pictures of women, and all male participants solely chose Instagram content of men. Furthermore, the current study showed that how Instagram affects body image differs among genders. More specifically, Thin Ideal and Body Positivity content was solely selected by women, whereas Fitness content was almost exclusively selected by men. In response to these different types of content, female participants reported both negative and positive emotions triggered through the Instagram content and how they socially engaged with it, whereas male participants only indicated positive emotions. This is in line with previous work by Casale and colleagues (2019), who showed that when men and women were exposed to same-sex attractive Instagram images, only women experienced increased dissatisfaction while men showed no significant effect.

A furthermore speculative—interpretation might be that, when it comes to body image, females could lean towards a more fixed mindset, while males may exhibit tendencies aligned with a growth mindset. Someone holding a fixed mindset believes that personal characteristics and traits cannot be changed (Walker and Jiang, 2022), as opposed to employing a growth mindset which refers to one’s confidence in the changeability of personal characteristics and traits, improving skills with practice and impacting attitudes and actions (Dweck and Leggett, 1988; Tao et al., 2022). According to this line of reasoning, female participants holding a more fixed mindset might feel like their body image was fixed and could not be changed, leading to more negative feelings towards themselves. Alternatively, males who held a growth mindset toward their body image might feel like they would be able to make a change and therefore experience more optimism and motivation. It is important to highlight that this conclusion is merely speculative and thus warrants future research. Overall, based on previous studies (Casale et al., 2019; Legkauskas and Kudlaitė, 2022; Twenge and Martin, 2020; Yurdagül et al., 2019) and the current study, it seems that gender plays an important role in the dynamics between exposure to Instagram content and body image, and it is therefore recommended to be included in future work.

Both within the public discourse and in the scholarly debate negative effects of social media use on youth’s body image and well-being have been pointed out by stressing the effects of detrimental (upward) social comparisons and feelings of envy (Gibbons and Gerrard, 1989; McCarthy and Morina, 2020; Pedalino and Camerini, 2022; Taylor and Lobel, 1989). The present study presents a more nuanced picture. The overall relationship between positive feelings and downward comparison was observed, but the results also highlighted instances where a positive emotional connection was established with upward social comparison. This was specifically the case in relation to the fitness category images selected by men. The discovery that “prior research has largely neglected that upward comparisons on social networking sites may also facilitate positive outcomes, specifically media-induced inspiration, a motivational state highly conducive to well-being” (Meier et al., 2020, p. 1) aligns with findings from fellow researchers who describe upward comparisons as potential motivational “pushes” (Diel et al., 2021). These studies and the current study suggest that different mechanisms are in place for different people and different content. Consequently, scholarly circles may no longer note that upward or downward social comparison makes one feel a specific way but that comparison in relation to the content and personality of oneself is what drives the effect.

During the evaluation of the study on the 5th diary study day, participants reported that the study design and procedure made them more conscious about their Instagram behavior and their body image and served as a helpful tool in better understanding how they navigate through their social media. Although unintended, the diary study turned out to be some sort of intervention tool that helped increase youths’ awareness of encountered body image triggers, comprehend internal processing, and allow participants to take a step back and view their relation with Instagram more consciously. This resulted in youth finding more self-love and appreciation for themselves. These encouraging positive effects have also been found through other programs aiming at awareness creation. For example, the Mindful Self-Compassion program by Neff and Germer (2012) found positive effects on self-compassion, mindfulness, and various well-being outcomes that lasted for up to one year after participation, showcasing the power of awareness creation. Although the current study was not set up as an awareness-creation program, it seemed to have created awareness among participants and might have more long-lasting effects on our participants than previously expected.

Strengths, limitations, and recommendations

The main strength of this study is that it aimed to entangle some of the complex interactions between youths’ Instagram content consumption and their body image. As one of the first qualitative approaches used in this field, this diary study uncovered youths’ habits, engagements, motivations, and feelings regarding their social media consumption. The frequent and real-time collection of data, which is part of the diary study design, enabled us to record youths’ answers in their natural environment, which has been proven to deliver more reliable results (Carter and Mankoff, 2005; Chun, 2016).

However, there are also some limitations that need to be taken seriously. First, our study results suggested that males tend to see more Fitness content and females tend to see more Thin Ideal and Body Positivity content and that that content is also differentially affecting their body image. However, males only comprised 21% of the whole sample which might have affected the reliability and generalizability of our findings. Additionally, this sample was highly dominated by German and Dutch participants. As body image seems to be a societally created construct, results may vary depending on different cultures and parts of the world, and our results do not apply to all youth (Sarwer and Polonsky, 2016; Sotiriou and Awad, 2020; Wardle et al., 1993). For future research, it would therefore be valuable to employ a more diverse sampling pool embodying more diverse backgrounds and an equal distribution of gender.

Second, the prompt that we used for each diary input, in which we asked participants to think about their own body image, might have directed participants in a certain direction. The wording of the prompt matters, as it might have been the case that the prompt used in this study encouraged participants to filter out Instagram content of the same sex. We specifically prompted participants to select the content that triggered “your body image”, potentially steering participants in the direction of selecting same-sex Instagram content as they might identify most with the body image of same-sex individuals on Instagram. Additionally, as participants had to identify one Instagram post each day, participants were ‘forced’ to use Instagram each day and actively search for content that was related to their body image. In a natural setting, participants might not have used Instagram each day or might have been differently impacted due to lower awareness. It is therefore recommended to—next to the diary study design—examine youths’ social media behaviors and engagement through less awareness-creation methods such as eye tracking or data scraping (Kohout et al., 2023; Song and Moon, 2018; Vergara et al., 2020).

Additionally, as there is no one-size-fits-all solution, it is suggested that future studies map out profiles for youth by investigating individual patterns across various diary study days. As this study has successfully identified trends among participants and highlighted the dominance of certain content categories, future research could investigate the effects of content on youths’ body image and their emotions. (Intensive) longitudinal designs (e.g., Hamaker and Wichers, 2017), in particular, would be well-suited to uncover fluctuations in these influences over time, providing a deeper understanding of the evolving dynamics between social media content and adolescents’ body image and well-being. Highlighting certain individual trigger points and insights into how youth regulate their emotions most adaptively will aid the development of targeted ways to help youth encourage a positive body image (Mahon and Hevey, 2021). This is especially important since the content that youth are exposed to is amplified by social media algorithms (Bozzola et al., 2022). In other words: being exposed to a lot of thin ideal content will trigger the exposure to more thin ideal content, creating a vicious cycle of the same type of content evoking certain emotions. Such individual cycles and the prominence of harmful content that could trigger specific individuals can be turned around by helping youth controlling the content that they are exposed to, for example, by applying filters (Mahon and Hevey, 2021).

Conclusion

The focus on quantitative research in the field of social media and body image has restrained the scientific research community from making sense of how social media content affects youth and how that happens. With the current study, we aimed to gather a deeper and more nuanced understanding of young people’s body image trigger points, uncovering their origin, the type of content, and the following emotional consequences. Results revealed that different types of content (i.e., Thin Ideal, Body Positivity, Fitness, and Lifestyle) on Instagram affected youths’ body image in different ways. Highlighting the complexity of this topic, it was shown that each content category did not always have the same effect on each individual: the same content could end up in either upward or downward comparison and either positive, negative, or neutral effects on mood. The results of this study highlighted that gender plays an important role in the dynamics between exposure to Instagram content and body image, and it is therefore recommended to be included in future work. In conclusion, the findings emphasize the significance of continuing research in this field, given the omnipresence of social media platforms like Instagram in the lives of young people.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and analyzed during the current study is available in DANS Data Station Social Sciences and Humanities, https://doi.org/10.17026/SS/7M90LJ.

References

Abi-Jaoude E, Naylor KT, Pignatiello A (2020) Smartphones, social media use, and youth mental health. CMAJ 192(6):136–141. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190434

Ahadzadeh AS, Pahlevan Sharif S, Ong FS (2017) Self-schema and self-discrepancy mediate the influence of Instagram usage on body image satisfaction among youth. Comput Hum Behav 68:8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.011

Aparicio-Martínez P, Perea-Moreno A, Redel-Macías MD et al. (2019) Social media, thin-ideal, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes: an exploratory analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(21):4177–4193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16214177

Arnett JJ (2007) Emerging adulthood: what is it, and what is it good for? CDP 1:68–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x

Arnett JJ, Žukauskienė R, Sugimura K (2014) The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 1:569–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7

Babaleye SOT, Wole A, Olofin NG (2020) Image promotion on Instagram by female students in some Nigerian universities. Adv Soc Sci 7(11):494–502. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.711.9177

Ben Ayed H, Yaich S, Ben Jemaa M et al. (2019) What are the correlates of body image distortion and dissatisfaction among school-adolescents? Int J Adolesc Med Health 33(5):20180279. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2018-0279

Beos N, Kemps E, Prichard I (2021) Photo manipulation as a predictor of facial dissatisfaction and cosmetic procedure attitudes. Body Image 39:194–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.08.008

Bodroža B, Obradović V, Ivanović S (2022) Active and passive selfie-related behaviors: Implications for body image, self-esteem, and mental health. Cyberpsychology 16(2). https://doi.org/10.5817/cp2022-2-3

Boeije HR (2009) Analysis in qualitative research. Sage Publications, London

Borinca I, Iacoviello V, Valsecchi G (2020) Men’s discomfort and anticipated sexual misclassification due to counter-stereotypical behaviors: The interplay between traditional masculinity norms and perceived men’s femininization. Sex Roles 85(3–4):128–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01210-5

Bozzola E, Spina G, Agostiniani R et al. (2022) The use of social media in children and adolescents: scoping review on the potential risks. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(16):9960–9993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169960

Brewster ME, Velez BL, Breslow AS et al. (2019) Unpacking body image concerns and disordered eating for transgender women: the roles of sexual objectification and minority stress. J Couns Psychol 66(2):131–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000333

Brown Z, Tiggemann M (2016) Attractive celebrity and peer images on Instagram: effect on women’s mood and body image. Body Image 19:37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.08.007

Bucchianeri MM, Arikian AJ, Hannan PJ et al. (2013) Body dissatisfaction from adolescence to young adulthood: findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Body Image 10:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.09.001

Burnette CB, Kwitowski MA, Mazzeo SE (2017) “I don’t need people to tell me I’m pretty on social media:” a qualitative study of social media and body image in early adolescent girls. Body Image 23:114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.09.001

Carrotte ER, Vella AM, Lim MS (2015) Predictors of “liking” three types of health and fitness-related content on social media: a cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res 17(8):205–221. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4803

Carter S, Mankoff J (2005) When participants do the capturing: the role of media in diary studies. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems. ACM Digital Library, Portland, pp. 899–908. https://doi.org/10.1145/1054972.1055098

Casale S, Gemelli G, Calosi C et al. (2019) Multiple exposure to appearance-focused real accounts on Instagram: effects on body image among both genders. Curr Psychol 40(6):2877–2886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00229-6

Chun CA (2016) The expression of posttraumatic stress symptoms in daily life: a review of experience sampling methodology and daily diary studies. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 38(3):406–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-016-9540-3

Cohen R, Fardouly J, Newton-John T et al. (2019) BoPo on Instagram: an experimental investigation of the effects of viewing body-positive content on young women’s mood and body image. N Media Soc. 21(7):1546–1564. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819826530

Cohen R, Newton‐John T, Slater A (2017) The relationship between Facebook and Instagram appearance-focused activities and body image concerns in young women. Body Image 23:183–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.10.002

Crone EA, Dahl RE (2012) Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat Rev Neurosci 13(9):636–650. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3313

Davis K, Weinstein E (2017) Identity development in the digital age. In: Wright M (ed) Identity, sexuality, and relationships among emerging adults in the digital age. IGI Global, pp. 1–17

Di Gesto C, Matera C, Policardo GR et al. (2022) Instagram as a digital mirror: the effects of Instagram likes and disclaimer labels on self-awareness, body dissatisfaction, and social physique anxiety among young Italian women. Curr Psychol 42(17):14663–14672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02675-7

Diel K, Grelle S, Hofmann W (2021) A motivational framework of social comparison. J Pers Soc Psychol 120(6):415–1430. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000204

Dittmar H (2009) How do “body perfect” ideals in the media have a negative impact on body image and behaviors? Factors and processes related to self and identity. J Soc Clin Psychol 28(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2009.28.1.1

Donovan CL, Uhlmann LR, Loxton NJ (2020) Strong is the new skinny, but is it ideal?: A test of the Tripartite Influence Model using a new measure of fit-ideal internalisation. Body Image 35:171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.09.002

Duan C, Lian S, Liu Y et al. (2022) Photo activity on social networking sites and body dissatisfaction: the roles of thin-ideal internalization and body appreciation. Behav Sci 12(8):280. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12080280

Dweck CS, Leggett EL (1988) A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol Rev 95(2):256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.95.2.256

Erikson EH (1968) Identity: youth and crisis. Norton & Company, New York

Eyal K, Te’eni-Harari T (2013) Explaining the relationship between media exposure and early adolescents’ body image perceptions. J Media Psychol 25(3):129–141. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000094

Fardouly J, Diedrichs PC, Vartanian LR et al. (2015) Social comparisons on social media: the impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image 13:38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.12.002

Feltman CE, Szymanski DM (2017) Instagram use and self-objectification: the roles of internalization, comparison, appearance commentary, and feminism. Sex Roles 78(5–6):311–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0796-1

Festinger L (1954) A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat 7(2):117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Franchina V, Lo Coco G (2018) The influence of social media use on body image concerns. Int J Psychoanal Educ 10(1):5–14. https://doaj.org/article/d015c7ad7b234986a16d27f9b51274c8

Fredrickson BL, Roberts TA (1997) Objectification theory: toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychol Women Q 21(2):173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Frisén A, Holmqvist K (2010) What characterizes early adolescents with a positive body image? A qualitative investigation of Swedish girls and boys. Body Image 7(3):205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.04.001

Gibbons FX, Gerrard M (1989) Effects of upward and downward social comparison on mood states. J Soc Clin Psychol 8(1):14–31. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1989.8.1.14

Granic I, Morita H, Scholten H (2020) Beyond screen time: identity development in the digital age. Psychol Inq 31(3):195–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840x.2020.1820214

Gunthert KC, Wenze SJ (2012) Daily diary methods. In Mehl MR, Conner TS (eds) Handbook of research methods for studying daily life. The Guilford Press, New York, pp. 144–159

Halliwell E, Dittmar H (2006) Associations between appearance-related self-discrepancies and young women’s and men’s affect, body satisfaction, and emotional eating: a comparison of fixed-item and respondent-generated self-discrepancies. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 32:447–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616720528400

Hamaker EL, Wichers M (2017) No time like the present: discovering the hidden dynamics in intensive longitudinal data. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 26(1):10–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416666518

Holland G, Tiggemann M (2016) A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image 17:100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008

Janssens KA, Bos EH, Rosmalen JG et al. (2018) A qualitative approach to guide choices for designing a diary study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 18(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0579-6

Kearney‐Cooke A, Tieger D (2015) Body image disturbance and the development of eating disorders. In: Smolak L, Levine MP (eds) The Wiley handbook of eating disorders. Wiley, New York, pp. 283–296

Keery H, Van Den Berg P, Thompson JK (2004) An evaluation of the Tripartite Influence Model of body dissatisfaction and eating disturbance with adolescent girls. Body Image 1(3):237–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.03.001

Kleemans M, Daalmans S, Carbaat I et al. (2016) Picture perfect: the direct effect of manipulated Instagram photos on body image in adolescent girls. Media Psychol 21(1):93–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2016.1257392

Kohout S, Kruikemeier S, Bakker BN (2023) May I have your attention, please? An eye tracking study on emotional social media comments. Comput Hum Behav 139:107495–107504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107495

Legkauskas V, Kudlaitė U (2022) Gender differences in links between daily use of Instagram and body dissatisfaction in a sample of young adults in Lithuania. Psychol Top 31(3):709–719. https://doi.org/10.31820/pt.31.3.12

Lewallen J, Behm-Morawitz E (2016) Pinterest or thinterest?: social comparison and body image on social media. Soc Media Soc 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116640559

Lister M (2022) 33 Mind-boggling Instagram stats & facts for 2022. WordStream. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2017/04/20/instagram-statistics#:%7E:text=8.,shared%20on%20Instagram%20per%20day. Accessed 11 Feb 2022

Lonergan A, Bussey K, Mond J et al. (2019) Me, my selfie, and I: the relationship between editing and posting selfies and body dissatisfaction in men and women. Body Image 28:39–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.12.001

MacNeill L, Best LA, Davis LL (2017) The role of personality in body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating: discrepancies between men and women. J Eat Disord 5(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-017-0177-8

Mahon C, Hevey D (2021) Processing body image on social media: gender differences in adolescent boys’ and girls’ agency and active coping. Front Psychol 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.626763

Manago AM, Graham MB, Greenfield PM et al. (2008) Self-presentation and gender on MySpace. J Appl Dev Psychol 29(6):446–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.07.001

Manning TM, Mulgrew KE (2022) Broad conceptualisations of beauty do not moderate women’s responses to body positive content on Instagram. Body Image 40:12–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.10.009

Marshall B, Cardon P, Poddar A et al. (2013) Does sample size matter in qualitative research?: a review of qualitative interviews in IS research. J Comput Inf Syst 54(1):11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2013.11645667

McCarthy P, Morina N (2020) Exploring the association of social comparison with depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Psychol Psychother 27(5):640–671. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2452

McLean SA, Rodgers RF, Slater A et al. (2022) Clinically significant body dissatisfaction: prevalence and association with depressive symptoms in adolescent boys and girls. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31(12):1921–1932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01824-4

Meier A, Gilbert A, Börner S et al. (2020) Instagram inspiration: how upward comparison on social network sites can contribute to well-being. J Commun 70(5):721–743. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa025

Michikyan M, Dennis J, Subrahmanyam K (2014) Can you guess who I am? Real, ideal, and false self-presentation on Facebook among emerging adults. Emerg Adulthood 3(1):55–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696814532442

Myers TA, Crowther JH (2009) Social comparison as a predictor of body dissatisfaction: a meta-analytic review. J Abnorm Psychol 118(4):683–698. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016763

Neff KD, Germer CK (2012) A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the Mindful Self-Compassion program. J Clin Psychol 69(1):28–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21923

Nesi J, Choukas-Bradley S, Prinstein MJ (2018) Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: Part 1—A theoretical framework and application to dyadic peer relationships. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 21:267–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0261-x

Parasecoli F (2005) Feeding hard bodies: food and masculinities in men’s fitness magazines. Food Food 13(1–2):17–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710590915355

Pedalino F, Camerini A (2022) Instagram use and body dissatisfaction: the mediating role of upward social comparison with peers and influencers among young females. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(3):1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031543

Pellerone M, Ramaci T, Granà R et al. (2017) Identity development, parenting styles, body uneasiness, and disgust toward food. A perspective of integration and research. Clin Neuropsychiatry 14(4):275

Perloff RM (2014) Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles 71(11–12):363–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6

Pouwels JL, Valkenburg PM, Beyens I et al. (2021) Social media use and friendship closeness in adolescents’ daily lives: an experience sampling study. Dev Psychol 57(2):309–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001148

Qi W, Cui L (2018) Being successful and being thin: the effects of thin-ideal social media images with high socioeconomic status on women’s body image and eating behaviour. J Pac Rim Psychol 12. https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2017.16

Quick V, Eisenberg ME, Bucchianeri MM et al. (2013) Prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction in young adults: 10-year longitudinal findings. Emerg Adulthood 1(4):271–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/216769681348573

Rafati F, Dehdashti N, Sadeghi A (2021) The relationship between Instagram use and body dissatisfaction, drive for thinness, and internalization of beauty ideals: a correlational study of Iranian women. Fem Media Stud. 23(2):361–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.1979065

Ralph‐Nearman C, Filik R (2020) Development and validation of new figural scales for female body dissatisfaction assessment on two dimensions: thin-ideal and muscularity-ideal. BMC Public Health 20(1):1114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09094-6

Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP (2001) Dietary restraint and negative affect as mediators of body dissatisfaction and bulimic behavior in adolescent girls and boys. Behav Res Ther 39(11):1317–1328. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00097-8

Richards D, Caldwell PH, Go H (2015) Impact of social media on the health of children and young people. J Paediatr Child Health 51(12):1152–1157. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13023

Saiphoo AN, Vahedi Z (2019) A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Comput Hum Behav 101:259–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.028

Sarwer DB, Polonsky HM (2016) Body image and body contouring procedures: Table 1. Aesthet Surg J 36(9):1039–1047. https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjw127

Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D et al. (2018) The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2:223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

Schilder P (1950) The image and appearance of the human body. Wiley & Sons, New York

Schuck K, Munsch S, Schneider S (2018) Body image perceptions and symptoms of disturbed eating behavior among children and adolescents in Germany. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 12:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-018-0216-5

Sebre SB, Miltuze A (2021) Digital media as a medium for adolescent identity development. Technol Knowl Learn 26(4):867–881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-021-09499-1

Slater A, Varsani N, Diedrichs PC (2017) #fitspo or #loveyourself? The impact of fitspiration and self-compassion Instagram images on women’s body image, self-compassion, and mood. Body Image 22:87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.06.004

Song H, Moon N (2018) Eye-tracking and social behavior preference-based recommendation system. J Supercomput 75(4):1990–2006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-018-2447-x

Sotiriou EG, Awad GH (2020) Cultural influences on body image and body esteem. In: Cheung FM, Halpern DF (eds) The Cambridge handbook of the international psychology of women. Cambridge University Press, pp. 190–204

Stapel DA, Schwinghammer SA (2004) Defensive social comparisons and the constraints of reality. Soc Cogn 22(1):147–167. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.22.1.147.30989

Stice E, Shaw HE (2002) Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology. J Psychosom Res 53(5):985–993. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00488-9

Tao W, Zhao D, Yue H et al. (2022) The influence of growth mindset on the mental health and life events of college students. Front Psychol 13:821206–821214. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.821206

Taylor SE, Lobel M (1989) Social comparison activity under threat: downward evaluation and upward contacts. Psychol Rev 96(4):569–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.96.4.569

Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe M et al (1999) Exacting beauty: theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. American Psychological Association

Thorisdottir IE, Sigurvinsdottir R, Asgeirsdottir BB et al. (2019) Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among Icelandic adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 22(8):535–542. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0079

Tiggemann M, Anderberg I (2019) Social media is not real: the effect of ‘Instagram vs reality’ images on women’s social comparison and body image. N Media Soc 22(12):2183–2199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819888720

Twenge JM, Martin GN (2020) Gender differences in associations between digital media use and psychological well‐being: evidence from three large datasets. J Adolesc 79(1):91–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.12.018

Tylka TL (2011) Positive psychology perspectives on body image. In: Cash TF, Smolak L (eds) Body image: a handbook of science, practice, and prevention. The Guilford Press, pp. 56–64

Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow NL (2015) The Body Appreciation Scale-2: item refinement and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 12:53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.09.006

Valkenburg PM, van Driel II, Beyens I (2021) The associations of active and passive social media use with well-being: a critical scoping review. N Media Soc 24(2):530–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444821106542

Verduyn P, Ybarra O, Résibois M et al. (2017) Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Soc Issue Political Rev 11(1):274–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12033