Abstract

Animal advocacy is a complex phenomenon. As a social movement encompassing diverse moral stances and lifestyle choices, veganism and vegetarianism (veg*) are at its core, and animal testing raises as a notably contentious issue within its members. This paper addresses this critical topic. Employing data from an international quantitative survey conducted between June and July 2021, our research explores how ethical vegans and vegetarians responded during the COVID-19 crisis. By comparing the experiences and choices between the two groups, we aimed to understand the variances in attitudes and behaviors in the face of an ethical dilemma, highlighting the interplay between personal beliefs and social pressures in times of a health crisis. Our findings reveal stark contrasts in how vegans and vegetarians navigated the pandemic; vegans displayed less conformity yet experienced a significant compromise of their ethical values, particularly in their overwhelming acceptance of vaccination. This study enhances the field of veg* research and social movement studies by exploring how a social crisis shapes members’ behaviors and perspectives. Our findings also contribute to a better understanding of the challenges and prejudices that a minority group such as vegans may face and how they cope with the pressure to go against the mainstream at a time when society is polarized by a single discourse that goes against their moral values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The enduring concern of animal experimentation sits at the heart of the animal defense movement, propelled by the humanitarian ethos established in the 19th century and the principles of anti-speciesism that emerged in the 20th century. At the same time, within the spectrum of animal advocacy, animal testing is one of the most contentious issues due to the scarcity of viable non-animal alternatives for drug testing and the broad spectrum of stances within the movement. These range from advocating for the outright abolition of animal testing to endorsing its restricted use under specific circumstances (Díaz, 2016; Newton, 2013). Animal testing intersects with a deeply personal and critical issue: human health.

The COVID-19 crisis, with its heavy reliance on preventive pharmacological interventions developed through animal testing, posed a profound ethical conundrum for animal advocates. Confronted with this unprecedented challenge, we conducted an exploratory study investigating how animal advocates navigated this situation. To capture and picture their perspectives during the COVID-19 2020–2021 period, we conducted an international quantitative study of self-identified vegans and vegetarians (hereafter also referred to as veg*), focusing primarily on their reactions to the mass vaccination drive—the only pharmacological measure against the crisis. We chose these two groups because of the inherent challenge of engaging with a diverse, dynamic, and evolving community. This choice aimed to encompass a breadth of animal advocates whose ethical stances might have been tested by the crisis. Moreover, contrasting these two communities provided a valuable comparative analysis, shedding light on the intricacies within the current animal defense movement.

Since the development of COVID-19 vaccines required animal testing by law, it left no compassionate alternatives that respected the interests of animals (Pruski, 2021). Simultaneously, massive media coverage following authorities and governmental organizations was deployed on the situation and measures (Krawczyk et al., 2021). In this context, it was reasonable to think that members of the veg* community, especially vegans, were at an ethical crossroads for facing the potential moral dilemma of choosing between safeguarding animals and protecting humanity.

This study offers a nuanced exploration of the moral quandaries confronted by the vegan and vegetarian community during a worldwide health crisis. Moreover, it illuminates the broader question of moral decision-making within groups whose values deviate from the mainstream, revealing the intricate interplay among personal convictions, societal pressures, and ethical considerations in times of unparalleled challenge.

Before presenting our findings, we will first delineate the distinctions between vegetarianism and veganism, focusing mainly on their stances regarding animal testing, describing the role of animal experimentation in the COVID-19 solution, and the social and media pressure during the period. Subsequently, we elaborate on our methodological approach. The article concludes with a discussion of our findings, exploring the broader implications of the COVID-19 crisis for the vegetarian and vegan communities.

Vegetarian and vegan views on animal testing

Contemporary vegetarianism has served as an umbrella term encompassing a variety of philosophical stances and dietary practices, each delineating varying degrees of animal product exclusion. This broad category encompasses those who identify as vegetarians yet engage in occasional meat consumption, as well as pescatarians and diverse classifications of ovo-lacto-vegetarians (Beardsworth and Keil, 1991; Beardsworth and Bryman, 1999; Jabs et al., 2000; Janda and Trocchia, 2001). However, the most holistic form of vegetarianism is “veganism,” sometimes referred to as authentic or proper vegetarianism (Willetts, 1997, p. 117) or strict vegetarianism (Rothgerber, 2014a). Introduced in 1944, the term veganism was initially intended to be distinguished from vegetarianism to cover a broader ethical philosophy that advocates living without harming, exploiting, or using nonhuman animals in any way (Díaz and Horta, 2020; The Vegan Society, 2022).

The literature has often confused vegetarianism with veganism without distinguishing between these distinct philosophies and lifestyles. However, their distinct identity is now increasingly recognized and supported by both theoretical and empirical research, highlighting the need for nuanced investigation of these separate phenomena (Kalof et al., 1999; Knight et al., 2004; Meng, 2009; Okamoto, 2001; Pribis et al., 2010; Povey et al., 2001; Rothgerber, 2014a). In addition, previous studies have highlighted the importance of paying attention to the underlying motivations that drive individuals towards these choices when studying veg* communities.

Both vegetarianism and veganism can be adopted for a variety of reasons. Traditionally, vegetarianism has been associated with health and personal well-being, and contemporary research supports that health remains one of the main reasons for its adoption (Fox and Ward, 2008; Hargreaves et al., 2021; Hopwood et al., 2020; Salehi et al., 2023). As for veganism, although a significant and growing number of people are adopting vegan dietary practices because of health benefits and, to a lesser extent, environmental concerns (Giraud, 2021; Janssen et al., 2016; Oliver, 2023; Peggs, 2020), its origin and practice are deeply rooted in animal rights and anti-speciesism movements (e.g., Díaz and Horta, 2020; Ploll and Stern, 2020). These fundamental tenets of “ethical veganism” bring animal advocacy to the forefront (BBC, 2020; Diaz, 2016, 2017a, 2017b; Panizza, 2020; Ruby, 2012) and have given way to what is now also known as “political veganism,” a stance that actively challenges “the routine harms created by social structures and systems […]; and which is conceived as a form of collective activism” (Cochrane and Cojocaru, 2022, p. 60; Kalte, 2020). It is also argued that veganism aligns with social justice principles, often associated with progressive or left-wing ideologies (Díaz, 2012, 2018; Dickstein et al., 2022). In the literature, it is crucial to distinguish between “ethical” vegetarians and vegans—who prioritize animal welfare and animal rights—and other figures, such as the “health conscious”, who are primarily guided by personal health benefits (Rozin et al., 1997).

Agreeing on definitive descriptions for veganism and vegetarianism presents its challenges. Despite this, it is widely acknowledged that both communities are united by shared moral values; most notably, a concern for animal welfare that varies in degree (Lund et al., 2016). These shared values have faced challenges, particularly when intersecting with health concerns, as seen during the Covid-19 crisis. The comparative analysis of the vegan and vegetarian communities enhances our understanding of the animal advocacy movement. This comparison becomes especially crucial in the context of animal experimentation, illuminating the process of moral decision-making in situations that test people’s foundational values. While vegetarians may have diverse views on animal experimentation, it is not a defining characteristic of the vegetarian ethic as defined by the Vegetarian Society (https://vegsoc.org/lifestyle/). Vegetarians tend to adopt a “usoanimalistic” approach, focusing primarily on dietary choices (Díaz, 2017b). In contrast, veganism encompasses a broader ethical commitment that goes beyond dietary choices and rejects all forms of animal use—including in products and services—with animal testing being a defining concern within vegan ethics (The Vegan Society, 2022; Díaz, 2017b).

Animal experimentation is a very sensitive and controversial issue in society in general and, especially, in the veg* communityFootnote 1 (Greenebaum, 2012; Pruski, 2021). There is a lack of literature comparing vegans and vegetarians in terms of their concerns about animal testing, but some research has already suggested a significant difference. For instance, vegans surveyed by Ploll and Stern (2020, p. 3259) self-reported a statistically higher level of animal-friendly behavior than vegetarians (and all other respondents) about animal testing and animal-based ingredients in their consumption of cosmetics. On the other hand, Miguel (2021) has shown that the UK Vegan Society’s labeling is stricter for products tested on animals than for food, confirming the differential nature of veganism in this respect.

Other empirical studies have provided evidence to support notable discrepancies between vegans and vegetarians that may impact how they perceive animal experimentation. For instance, research indicates that vegans harbor more favorable attitudes towards animals, perceive a more significant similarity between humans and other species, and attribute a broader range of emotional and cognitive capacities to nonhuman animals compared to vegetarians (e.g., Filippi et al., 2010; Rothgerber, 2014a). Furthermore, vegans tend to express stronger condemnation of animal killing and experience higher guilt associated with such practices when juxtaposed with vegetarians (Ruby and Heine, 2011). Regarding emotional responses, vegans show elevated levels of disgust and sensitivity towards the consumption of animals, along with greater empathy for animal suffering (Rothgerber, 2014b; Rothgerber, 2015). Lastly, veganism is usually associated with a greater emphasis on nonhuman animal advocacy (Hoffman et al., 2013; Piazza et al., 2015).

Animal experimentation and discrimination in COVID-19

More than 192.1 million nonhuman animals are used in research worldwide every year on average, according to estimations (“Facts and Figures on Animal Testing”, n.d.). However, the exact number is unknown due to the lack of transparency by both regulators and experimenters. Mice, rats, and other rodents are used the most, yet many other species—such as cats, dogs, horses, birds, pigs, fishes, sheepsFootnote 2, goats, reptiles, and nonhuman primates—are also used in experiments devised by scientists and approved by public and private scientific committees under strict rules of confidentiality. In these experiments, nonhumans are used in several types of research. Among the most common are basic research (e.g., genetics, developmental biology, behavioral studies), applied research (e.g., biomedical research, xenotransplantation), drug and toxicology testing, education research (mainly at universities), breeding research (genetic selection), and defense research (by governments and the military). Details of the practices to which they are subjected (e.g., smoke inhalation, ingestion of chemicals, infection with disease, brain damage) are often kept secret from the public, who are increasingly sensitive to cruelty to animals. However, occasionally, information about research involving animals that humans are fonder of—such as dogs and cats—and leaks of malpractice reach the media (e.g., Kassam and Grover, 2021).

At least since Ancient Greece, animal research has been used for scientific and medical purposes (Guerrini, 2022). However, controversy about the efficacy of animals as research models for human medicine is high at present, with strong evidence showing very poor results from the animal model due to methodological, scientific, and technical problems (Akhtar, 2012a, 2012b, 2015; Herrmann and Jayne, 2019; Knight, 2011; Leyton, 2019)Footnote 3. Despite this, animal experimentation is currently compulsory worldwide by law or de facto for drugs and toxicology, being authorized by regulators before any human test is conducted and launched into the market (Knight, 2011; Leyton, 2019)Footnote 4.

Animal testing has particularly been a critical component of vaccine development. Since Jenner, at the end of the 18th century, animals have been used as potential models for human infectious diseases (Gerdts et al., 2007). Mainly since Pasteur, during the 19th century, animal pathogens have been used attenuated or as vectors in vaccines, and researchers have been experimenting with the transmission of different pathogens to different animal species and between individuals of different animal species. In addition, most vaccines have been developed using small animals like rodents as test subjects—so-called “‘models” by the industry, animals that the industry makes sick to test drugs on them. However, studying and testing on larger animals, including calves, horses, sheep, pigs, guinea pigs, and nonhuman primates, has also become common. Sometimes, their body parts or body fluids are used for scientific purposes. For instance, for the last 70 years, the most common way of manufacturing flu vaccines has used hens’ eggs (“How Flu Vaccines are Made”, n.a.).

The technology most used for COVID-19 inoculations (messenger RNA-based, or mRNA) does not use attenuated pathogens anymore, but animal experimentation has also played an important role in these drugs. The mRNA technology has been researched in laboratories since at least 1990, including nonhuman animals in the different stages of research (Pardi et al., 2018). Scientists also conducted specific animal tests with, at least mice and nonhuman primates in the preclinical phase of the specific preparations marketed for COVID-19 (NIAID Now, 2021). Therefore, even if the animal trials for the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines were faster than usual (because there were no long-term studies) and thus fewer animals were used for shorter periods, these drugs still involved the testing and killing of a considerable number of small and large animals over more than two decades.

Some authors point out that this crisis has brought some (apparently) positive results for animals; for example, the increase in the number of “companion animal” guardians, mainly to alleviate social isolation measures during this crisis (with some associated market booms) (see on this van Wyk, 2022). However, the period has also brought an escalation of prejudice, neglect, abuse, and the killing of animals, along with an increase in speciesism, which undoubtedly challenges vegan values. For instance, the COVID-19 crisis involved the mistreatment of animals in ways other than experimentation that are likely to concern vegans and animal rights advocates; amongst the most important is the augmented prejudice raised against some free-living animals (Bittel, 2020), “companion” animals (Zhang et al., 2020; Berry, 2020; Feng, 2021), captive animals (Haworth, 2020), or farmed animals (Kesslen, 2020).

Veg* philosophies and lifestyles are increasingly common in Western societies, but people who embrace them remain a source of stigma (Rosenfeld and Tomiyama, 2020; Vandermoere et al., 2019). As MacInnis and Hodson (2017) point out, it is paradoxical that vegetarians and vegans become the subject target of bias or prejudice even though they do less harm to animals and the environment. Veg* individuals are seen as “symbolic threats”, understood as “intangible threats to an ingroup’s beliefs, values, attitudes, or moral standards” (p. 724). Furthermore, research on perceptions of the veg* community by the non-veg* community shows that vegans experience more prejudice and discrimination than vegetarians (MacInnis and Hodson, 2017; Judge and Wilson, 2019). The media often contributes to exacerbating this view. For example, Cole and Morgan (2011), who studied the representation of veganism in UK newspapers, found that veganism was portrayed as “contrary to common sense” because it fell outside the dominant discourses on animal exploitation. Not only did the newspapers tend to discredit veganism, but vegans were also stereotyped as “ascetics, faddists, sentimentalists, or in some cases, hostile extremists” (p. 134). The authors refer to this pejorative discourse as “vegaphobia”: a cultural reproduction of speciesism that helps mask and perpetuate the exploitation of nonhuman animals while marginalizing veganism and vegans (Cole, 2015). From a philosophical stance, Horta (2018) has also labeled the bias against vegans as an unjustified “second-order discrimination, that is, discrimination against those who oppose another (first-order) form of discrimination” (p. 1).

This backdrop of misunderstanding and hostility towards the veg* individuals set the stage for the challenges presented during the COVID-19 crisis. General vaccination coverage varied widely from 62% to 82% (proportion of people with a complete initial protocol) (Our World in Data, n.d.). However, specific data on vegan vaccination rates—globally or by country—is notably absent, which leaves a gap in our understanding of how this community navigated the pandemic’s unique ethical landscape. During our studied 2020–2021 period, the moral dilemma posed by animal-tested COVID-19 vaccines framed the veg* community within a complex media narrative by subjecting their choices to intense scrutiny within broader public health discourse and highlighting an ethical quandary more acute for vegans than for vegetarians. Vegans are often depicted as grappling with the moral implications of receiving vaccines tested on animals. They are frequently mentioned in this context and sometimes portrayed in a pejorative light, with descriptors such as “dogmatic,” “ultra-pedantic,” and “no different than a blindly partisan Trump follower who would rather harm their country than lose a political fight” (Catalunya Press, 2021; Bramble, 2021; Herzog, 2022; Sun, 2021).

Nevertheless, public discourse from vegans primarily reflects a neutral or pro-vaccination stance (Sainz, 2021; De la Paz, 2021; Turner, 2021). Influential figures within the vegan community have promoted vaccination, often sharing their own vaccination experiences on social media (Nelson, 2022) and participating in advocacy campaigns (Esselstyn Family Foundation, 2021). At the same time, many dissenting opinions received no media coverage, as in the case of the summit of critical vegans discussing vaccination (Worldwide Vegan Summit for Truth and Freedom, 2022), whereas individual vegans supporting vaccination (Francione, 2020; Singer, 2021) were given visibility in the media worldwide. For instance, Singer (2021) did not refer to the cost of the vaccine to animals and asserted that the COVID-19 vaccine should be mandatory. In this context, some vegetarians requested vegans to make an exception and avoid “extremism” (e.g., Bramble, 2021; Davis, 2021; Enerio, 2021; Sun, 2021). This public pressure on vegans was intensified with the publicized statements of key vegan organizations, such as PETA (Sachkova, 2021), Animal Aid (“COVID-19 Vaccines and Veganism”, 2021), and The Vegan Society (“Vegan Society response to COVID-19 vaccine”, 2020); PETA explicitly recommended vegans to get vaccinated to preserve the health of others and their own health to continue defending animals, and the same idea is evident in the Vegan Society’s official statement on the COVID-19 vaccine.

This context provides fertile ground for academic inquiry. As far as the authors know, only a few studies on veganism and COVID-19 have been published to date. Most of these studies have focused on examining consumption trends and perceptions of veganism (Loh et al., 2021; Park and Kim, 2022; You, 2020; Tumanyan, 2021) or vegan food and products (Dinh and Siegfried, 2023; Lee and Kwon, 2022). On the other hand, Pruski (2021), a clinical scientist, recalls the legitimate safety and conscience concerns about vaccination and cites vegans as an example of a morally committed community that does not agree with animal testing. However, none of these studies specifically address attitudes, experiences, and opinions or focus on animal testing. Similarly, none of these studies examine possible differences between vegans and vegetarians about vaccination and other measures taken during the COVID-19 crisis.

The current study

This study delves into the intricate moral conundrum ethical vegans and ethical vegetarians (hereafter, vegans and vegetarians) faced during the COVID-19 crisis. By comparing the experiences and choices between the two groups, we aim to understand the variances in attitudes and behaviors in the face of a global ethical dilemma, highlighting the interplay between personal beliefs and social pressures in times of a health crisis. Specifically, the study focuses on analyzing possible differences between self-proclaimed vegans and vegetarians on (1) attitudes and behavior towards vaccination; (2) attitudes towards COVID-19 Certificate, also known as “the Green Certificate” or “the Green Passport”, as proof of vaccination to facilitate free movement between countries; (3) the level of trust towards different groups about decisions made regarding COVID-19; (4) the sources of information used to learn about COVID-19; (5) the perceived level of censorship of information about COVID-19; and (6) the level of stress encountered during 2020 and 2021. In addition, we studied the extent to which being vegan or vegetarian, and the factors mentioned above affected the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Our starting point was that vegans and vegetarians might exhibit different attitudes and behaviors toward various COVID-19-related issues based on distinctions identified in existing literature. Particularly concerning COVID-19 vaccination, which involved animal testing, we hypothesized a significant divergence in acceptance rates between vegans and vegetarians, with the former being less likely to accept vaccination. Additionally, we anticipated potential disparities between the two groups regarding their trust in social actors (such as the media), their choice of information sources, and their perceptions of information censorship during the pandemic. These expectations stem from the perception of veganism as the “most radical” stance within the veg* community and its minority status in a predominantly non-vegan society. It stands to reason that vegans might exhibit more skepticism, critique, or detachment from conventional information channels and societal institutions. However, we do not formulate specific hypotheses on these aspects—or the level of stress suffered by the two groups—given the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 crisis and the paucity of research in this area.

Method

Questionnaire

The study used a structured, non-randomized online survey available in English or Spanish. Data were collected between June and July 2021. In addition to sociodemographic data (age, gender, country of residence, educational level, employment status, and political ideology), the survey included questions related to the following issues:

-

Lifestyle/philosophy of life: Participants were asked to indicate which option seemed most appropriate to describe their current lifestyle/philosophy: vegan, vegetarian, ovo-vegetarian, lacto-vegetarian, ovo-lacto vegetarian, flexitarian, pescatarian, plant-based diet, or others (presented as an open question).

-

Motivations for maintaining the lifestyle/philosophy of life: On a 5-point Likert scale, participants rated the relevance of the following motivations to maintaining their veg* lifestyle/philosophy of life: animal defense, environment, health, beauty, climate change, personal circle, spirituality, religion, and disgust.

-

Rejection and acceptance of animal use: Participants rated their acceptance of the use of animals in experimentation, food, entertainment, and fashion using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”. The variable was also used to determine the differential stance between vegans and vegetarians on the use of animals, with a particular focus on experimentation.

-

COVID-19: This section covered a variety of questions related to vaccination: doses received, motivations, opinions on mandatory vaccination, and possession of a COVID-19 passport (hereafter referred to as a green passport). The types of questions varied: some were dichotomous (e.g., “Have you received the COVID-19 vaccine? 1. no; 2. yes”), others offered multiple choices (e.g., “I have not been vaccinated …. 1. but I plan to do it as soon as possible”). Some questions allowed for multiple responses, with an open question (e.g., “If vaccinated, the main reasons are…: own health protection”). For some questions, a 5-point Likert scale was used (e.g., “Please rate your agreement with the statement: “COVID-19 vaccination should be compulsory for all citizens”, where 1 means “strongly disagree” and 5 means “strongly agree”).

-

Trust: We measured participants’ trust in different social actors during COVID-19 using a single 5-point Likert scale question: “Please rate your confidence that the following institutions will perform adequately during COVID-19”. There were eight categories: “Intergovernmental Institutions (WHO, agencies, etc.)”; “Government Institutions (state, federal, local, etc.)”; “Media”; “Pharmaceutical companies”; “Non-pharmaceutical companies”; “NGOs”; “Scientists”; “Healthcare professionals”. This question was designed according to the Trust Barometer methodology used globally by the independent communications firm Edelman Trust Institute (2021) for the past two decades.

-

Source of information: We measured this variable with two 5-point Likert scale questions, one on general topics and one on COVID-19: “How often do you use the listed sources to get general news?” And “How often have you used the listed sources to get updates related to COVID-19 (developments, vaccines, etc.)?”. Sources of information included: “Traditional media (both print and digital associated with large media groups)”; “Alternative media (both print and digital not associated with large media groups)”; “Social networks (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, etc.)”; “Private chats (WhatsApp, Telegram, etc.)”; “Personal networks (family, friends, etc.)”; “Experts (sociologists, psychologists, political scientists, doctors, philosophers, etc.)”; and “Other.”

-

Stress: We asked participants to evaluate in two 5-point Likert scale questions the level of stress they suffered, respectively, during 2020 and at the time of responding to the questionnaire, 2021.

Procedure and sample

The online survey, hosted on the website [details omitted for double-anonymized peer review] and administered through EncuestaFacil.com, was disseminated through vegetarian communities (e.g., animal protection groups), social networks (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit) and the researchers’ networks. We also used snowball sampling, asking participants to distribute the survey among their veg* contacts. The resulting data were analyzed for missing entries, outliers, and errors, and problematic data were excluded. As a result of this analysis, the initial sample of 1073 individuals was reduced to 936 persons. Of this sub-sample, 66% declared themselves vegans, 27% vegetarians (ovo-vegetarians, lacto-vegetarians, and ovo-lacto-vegetarians), 3% pescatarians, 2% plant-based diet, and 2% flexitarians. However, the final sample used for the analysis in this study consisted of 853 individuals as a result of applying two selection steps. First, flexitarians, pescatarians, and plant-based were excluded; the first two figures include animal consumption, and the last one remains ambiguous in the literature. Secondly, the analysis was specifically tailored to focus on individuals committed to veganism or vegetarianism for ethical reasons. Consequently, participants who did not identify animal protection as “important” or “very important”—using a 5-point Likert scale—as a reason for their dietary choices were excluded from the study.

Our final sample (n = 853) included a vegan sample of 66% (n = 587) and a vegetarian sample of 34% (n = 266). Regarding gender, 69% identified themselves as “women”, 27% as “men”, and 4% as “other”, with an average age of 36.7 years—37.6 years for vegans and 34.8 years for vegetarians. Almost all participants were highly educated. They predominantly identified with progressive, socialist, or anarchist political ideologies and supported feminist and environmentalist causes. Over half were paid-employed (see Table 1 for more detailed sample demographics). The sample boasted an international profile, with participants spanning 48 nations, primarily from Spain (53%) and the United States (15%). Notable representations also came from the United Kingdom (4%), Canada, Germany, Switzerland, Argentina (3% each), and smaller percentages (2%) from other countries, Austria, Australia, Portugal, and Mexico. Other participants came from Belgium, Colombia, Italy, India, Ireland, and the Netherlands, each representing 1%. All other nations accounted for less than 1% each. Given the strategy to collect the data, it should be noted that the results cannot be deemed statistically representative of the entire veg* community.

Analytical strategy

Due to the non-normal distribution in most cases, non-parametric tests were used in the analyses. Specifically, Spearman’s tests were used to study correlations between variables, while Chi-square and Mann–Whitney tests (with Bonferroni correction) were used to examine differences between vegan and vegetarian groups. Finally, binomial logistic regression was performed to assess the impact of the main factors studied, including vegetarianism or veganism, on vaccination decisions. Before analyzing COVID-19-related differences between vegans and vegetarians, we examined whether their views on the use of animals differed. As Table 2 indicates, both groups showed significant differences in all items, with a p < 0.001 and an effect size ranging from low to moderate. Vegans showed a more critical attitude towards all uses of animals. Using animals in experimentation is the least rejected for both groups when comparing all the uses included in the study.

Results

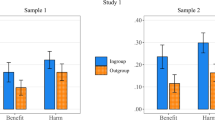

Attitudes, behavior, and reasons regarding vaccination

Differences in attitudes towards vaccination

The descriptive analysis of participants’ attitudes towards vaccines in 2021 (the time of the survey) revealed that the majority considered the vaccine safe or very safe for humans (68%) and effective or very effective against COVID-19 (71%). When we compared the attitudes of vegans and vegetarians concerning these attributes, we found that vegans rated them more negatively (see Table 3). In the case of safety, 64% of vegans versus 77% of vegetarians considered it “safe” or “very safe”; in contrast, 11% of vegans and 6% of vegetarians rated it “not very” or “not at all safe”. As for the vaccine’s efficacy, 66% of vegans vs. 82% of vegetarians considered it “effective or very effective”. In comparison, 10% of vegans vs. 5% of vegetarians perceived it as “not very” or “not at all effective”. However, the Mann–Whitney U-test indicated that the only significant difference (with a p = 0.025) was in the case of safety.

We also looked more closely at the group that chose the “don’t know enough” (DK) option about the attributes of safety (12% of the total sample) and vaccine efficacy (8% of the total sample). When comparing the two groups, we found that more vegans (13% for safety and 10% for efficacy) than vegetarians (10% and 3%, respectively) had chosen that option. However, these differences were significant for the assessment of vaccine efficacy (χ2(1, N = 68) = 12.98, p < 0.001) but not for vaccine safety (χ2(1, N = 101) = 2.30, p = 0.129).

When participants were asked about their views on mandatory vaccination against COVID-19, 41% of all participants agreed or strongly agreed with the measure. Comparing this attitude between the two groups, a more positive assessment was observed among vegetarians. On the one hand, 37% of vegans versus 51% of vegetarians accepted the measure (with 12% and 23%, respectively, responding “very agree”); on the other hand, 45% of vegans versus 26% of vegetarians rejected it (with 25% and 11%, respectively being “strongly disagree”). The Mann–Whitney U test confirmed these differences as statistically significant (see Table 3).

Regarding the possible implementation of the Green Passport, 52% of the sample considered it appropriate. Again, differences were observed when comparing the two groups: 48% of vegans and 60% of vegetarians agreed with its implementation (21% vs. 33% answered “strongly agree”); at the same time, 30% of vegans and 128% of vegetarians disagreed (19% and 11% respectively chose “strongly disagree”). The Mann–Whitney U-test confirmed that these differences were statistically significant (see Table 3).

We also examined the “don’t know enough” (DK) option on the Green Passport implementation. In this case, we also found that more vegans (13% and 10% for safety and effectiveness, respectively) than vegetarians (10% and 3%) chose DK. However, the difference was not significant (χ2(1, N = 74) = 1.06, p = 0.303).

We conducted a correlation analysis to explore the relationship between the four variables. We found strong and significant correlations between them for both groups (slightly stronger among vegans) (see Table 12 in Annex). Lastly, we also observe positive and significant correlations between the DK options. We found an association between vaccine safety and effectiveness (rho = 0.51, p < 0.001) as well as Green Passport with vaccine safety (rho = 0.11, p < 0.001) and effectiveness (rho = 0.12, p < 0.001).

Differences in behavior toward vaccination

Of all the participants, 85% reported being vaccinated against COVID-19 at least once. However, this percentage varied significantly between the two groups, with a lower proportion among vegans (82%) than vegetarians (94%) (χ2(1, N = 853) = 21.1, p < 0.001).

When examining the average number of doses received by participants in more detail, we found differences between the two groups (see Table 4). Specifically, although most respondents reported receiving two doses (73%), the percentage was significantly lower among vegans (69%) than among vegetarians (81%). We also analyzed the vaccinated individuals’ intention to receive additional booster doses (see Table 4). Data show that participants’ attitudes varied depending on whether they considered receiving a second, third, or subsequent dose. For instance, among those who had already received two doses, over 70% were willing to receive a third dose if necessary; however, only 3% expressed a willingness to receive a fourth dose. When comparing the two groups, we found no significant differences in the willingness to receive subsequent doses after the first shot (see Table 4). However, the findings regarding the number of doses received should be interpreted with caution due to potential variations in health recommendations, protocols, and vaccine brands, both between and within countries.

Among the unvaccinated (15% of the total sample), most participants reported not intending to receive any doses; this percentage was significantly higher among vegetarians. A significant difference was also observed for the option “I am still evaluating the possibility of getting vaccinated”, where the percentage was higher among vegans (see Table 5).

Differences in reasons for vaccination

In the total sample, three reasons appear as the most relevant for participants to be vaccinated: the feeling of “social responsibility”; “the desire to protect significant others (e.g. family, friends) as well as people in vulnerable situations”; and “the desire to safeguard their own health” (Table 6). It should be noted that participants could choose a maximum of three motives.

When comparing the vegan and vegetarian groups concerning these motives, we found significant differences in “protection of the significant others and vulnerable people (e.g., family, friends)” as well as in “protection of one’s health.” In both cases, the vegetarian sample indicated higher values (see Table 6).

To better understand the differences between the two groups in their decision-making regarding vaccination, we asked them to rate their agreement level on six questions related to vaccination, their lifestyle/philosophy, and animal welfare. As summarized in Table 7, the data revealed significant differences in all questions. First, a higher percentage of vegans (46%) than vegetarians (21%) believed that vaccination was not coherent with their lifestyle/philosophy. Additionally, 11% of vegans and 21% of vegetarians stated that they “did not think about its coherence.” It should be noted that this variable correlated positively and significantly with the attitudes towards mandatory vaccination (rho = 0.40; p < 0.001). Specifically, the less they considered the consistency of vaccination with their values, the more they supported mandatory vaccination.

Second, a higher percentage of vegans indicated that their lifestyle/philosophy had a significant influence on their vaccination decision; specifically, 12% of vegans, compared to 5% of vegetarians, stated that their veganism or vegetarianism influenced their decision quite a lot, while 50% of vegans and 70% of vegetarians responded that it did not influence their decision at all.

Third, vegans are less likely than vegetarians to accept the idea that vaccine testing on animals was done for a good cause or the common good (12% vs. 32%, respectively). Furthermore, vegans—compared to vegetarians—are more likely to recognize that vaccination involves animal suffering (80% versus 49%) and to express that they took this suffering into account in their decision-making process regarding vaccination (55% vs. 19%, respectively).

Lastly, the data revealed that a more significant proportion of vegans (4%) than vegetarians (1%) attempted to compensate for the perceived suffering associated with the COVID-19 vaccine by donating to various causes, such as sanctuaries or alternative animal testing centers (χ2(1, N = 852) = 7.82, p = 0.005; ⌀ = 0.10).

Differences in trust, the use of sources of information, censorship, and stress during COVID-19 crisis

We also examined possible differences in four variables that could influence veg* decisions and experiences during the period: (1) the level of trust in various social actors; (2) the use of different sources of information on COVID-19-related issues; (3) the perception of information censorship during the COVID-19 crisis; and (4) the level of stress in 2020 and 2021. Tables 8 and 9 summarize the results.

As for assessing the performance of the different social actors during the COVID-19 crisis, we found that healthcare—followed by scientists—was the best rated, while the media was the worst rated by the entire sample. When comparing vegans and vegetarians in this assessment, the data show that vegetarians were significantly more positive about the decisions made by four actors that were key during the crisis: healthcare, scientists, intergovernmental institutions, and pharmaceutical companies.

Regarding the different sources of information consumed to keep up to date, the Mann–Whitney U-test revealed two significant differences between the two groups (see Table 9). First, vegetarians consumed significantly more information from traditional media than vegans, both for information on COVID-19 issues and world events in general. Second, vegetarians relied more on information from their close circle to keep them informed about COVID-19 issues.

Additionally, the analyses showed that vegans significantly considered that there was more censorship of information about COVID-19 than vegetarians; however, this result should be taken with great caution given the p-value so close to the cut-off point. Finally, we compared the perceived stress levels of the two groups during 2020 and 2021. The man Whitney U-test revealed that vegetarians felt more stressed than vegans, but the difference was only significant for 2020.

Finally, we compared the perceived stress levels of the two groups during 2020 and 2021. The man Whitney U-test revealed that vegetarians felt more stressed than vegans, but the difference was only significant for 2020. It should be noted that higher levels of perceived stress and, especially, higher levels of censorship were positively and significantly related to being vaccinated ([stress2020] χ2(4, N = 645) = 0.26, p < 0.001; [stress2021] χ2(4, N = 645) = 0.18, p < 0.001; [censorship] χ2(4, N = 645) = 0.59, p < 0.001). In addition, they are related to attitudes toward vaccination, trust in different social actors, and the use of information sources (see Table 12 in Annex).

Factors influencing the decision to be vaccinated

To investigate the drivers of inclination to vaccinate within the total sample and each group, we conducted a binomial logistic regression, with the probability of vaccination (No/Yes) as the dependent variable. The following independent variables were included in the analysis: being vegan (versus vegetarian), vaccine attributes (safety, effectiveness, coherence, implications for animal suffering), trust in social actors, sources of information (in general and regarding COVID-19 issues), perceived censorship, and perceived stress (2020 and 2021) and sociodemographic variables (age, gender, educational level, countries of residence, and political ideology) as control variables. We first analyzed only the influence of veganism in the model. In the second step, non-significant variables were excluded using a joint omitted variables approach to improve the model fit. We analyzed the whole sample and the two groups (vegans and vegetarians) separately (see Tables 13–15 in the Annex for more models).

When we analyzed the factor of being vegan versus vegetarian in the decision to vaccinate, we found that it significantly and negatively influenced the decision to vaccinate (Model #1). However, the explanatory value was very low, as shown by the two pseudo-R2s (R2McFadden or R²McF; R2Nagelkerke or R²N), which accounted for 2% and 3% of the variability.

In the final binomial logistic regression, keeping all significant variables together (Model #2) showed five significant predictors of the vaccination decision for the whole sample. As shown in Table 10, participants were significantly more likely to be vaccinated if they considered the vaccine safe for humans, effective against COVID-19, and coherent with their veg* values. Furthermore, participants who exhibited lower trust in non-pharmaceutical companies or higher trust in media sources were significantly more inclined to get vaccinated. More importantly, identifying as vegan (versus vegetarian) was no longer a significant predictor of the decision to vaccinate when considered alongside other variables in our statistical model. Mediation effects in the model could explain this, as we found vaccine safety, veg* coherence, and trust as mediators during the analyses (see Table 13 in Annex). The final model fit measures indicated a good fit with lower complexity (AIC = 339; BIC = 400). The two pseudo-R2 showed that the model explained 56% and 66% of the variability.

We found some differences when we analyzed the groups separately (Table 10). In the vegan group, three factors influenced the likelihood of being vaccinated. Specifically, having a positive perception of the vaccine’s safety for humans, the vaccine’s efficacy, and the perception of its coherence with their vegan lifestyle/philosophy increased the likelihood of vaccination. The two pseudo-R2 showed that the model explained 51% (R²McF) and 63% (R²N) of the variability. In the vegetarian group, only having a positive perception of the vaccine’s safety for humans increased the likelihood of vaccination. In this case, the two pseudo-R2 tests showed that the model explained 70% (R²McF) and 74% (R²N) of the variability.

Discussion

Despite the persistent exploitation of nonhuman animals for human benefit across industries, there is growing recognition of animals as sentient beings—a status that is catalyzing legislative protections, integration of welfare policies into corporate practices, and changes in individual behaviors in different countries (Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act, 2022; Blattner, 2019; Harris, 2021; Ley 17/2021, 2021; Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, 2009). Primarily driven by animal advocates, the movement is diverse and dynamic, and rooted in varied philosophical beliefs (Wolf, 2014) that give rise to numerous moral positions and lifestyle choices regarding animal defence and human use. Animal experimentation emerges within this field as an especially contentious subject, stirring up division within the animal advocacy movement and sparking vigorous ethical discourse. Faced with COVID-19, a global crisis of unprecedented proportions, the challenge to this movement was also unprecedented. To our knowledge, our study is the first to explore the specific reactions of self-identified ethical vegans and vegetarians to the dilemmas posed by the COVID-19 crisis, exploring their attitudes, behavior, and experiences during 2020 and 2021. We now turn to the key findings of our research.

Despite its exploratory nature, our study reveals distinct differences between vegans and vegetarians during the COVID-19 crisis. Our findings broadly delineate the following differences: (i) attitudes and behavior towards vaccination and vaccination rates; (ii) motivations behind choosing to vaccinate and factors explaining their decision to be vaccinated; (iii) perceptions of vaccination consistency with their veg* lifestyle or philosophy; (iv) degrees of conformity with decisions from social actors and crisis-related information; and (v) preferences for traditional information sources on general and COVID-19 specific topics and level of perceived censorship.

Firstly, our vegan respondents are less complacent about vaccination during the COVID-19 crisis than vegetarians. Specifically, vegans show a more negative view of vaccinations, mandatory regulations, and restrictive passports than vegetarians. We also found significant differences between vaccination rates, with fewer vegans being vaccinated. Furthermore, vegans show greater intention to remain unvaccinated as well as more reluctance to continue vaccination when they are already vaccinated. Additionally, vegans not only consider that there has been a higher degree of censorship than vegetarians but also have less trust in the three institutions that made critical decisions during the crisis: intergovernmental bodies, pharmaceutical companies, and scientists. Thus, our results suggest that there is a difference of opinion between vegans and vegetarians regarding the response of institutions and society to vaccination, which places vegans in a more critical stance towards an activity that involves animal testing. This finding aligns with the fact that the literature critical of animal experimentation is typically led by vegan authors (e.g., Horta and Cancino-Rodezno, 2022).

Vaccination rates within our sample—82% for vegans and 94% for vegetarians—surpass the international averages recorded during our study period, which ranged from 62% to 82% (these international averages include the ten countries that account for 87% of our respondents). However, it is crucial to recognize the challenges in comparing vaccination data, especially coming from different countries. Consistent, comparable, and internationally aggregated data are scarce. Caution is advised when comparing the number of doses received between the two groups and internationally, as the disparity may be due to multiple factors beyond lifestyle (or diet) choices to including areas or country-specific vaccine accessibility, specific indications for each vaccine brand, public health recommendations, or vaccination protocols.

Secondly, the motivations for vaccination varied between vegetarians and vegans. Although both vegans and vegetarians consider the protection of others as a primary reason for vaccination, it is noteworthy that vegans attach comparatively less importance to the protection of their personal health. This result is reinforced in the logistic regression when it turns out that, for vegetarians, the factor that explains a large amount of variance is the concept of human security. In contrast, for vegans, the likelihood of vaccination was explained by multiple factors, including the assessment of the level of consistency of the vaccine with their philosophy of life. This difference may suggest a variation in motivational focus, with vegans showing a relatively more complex decision and higher priority on altruism. This pattern supports previous findings, including those indicating that vegans score higher levels on several aspects of “heartfulness” than vegetarians (Voll et al., 2023), a quality associated with mindfulness and prosocial behavior—characterized by caring, compassion, gratitude, and nurturance. Additional research has shown that vegetarians and vegans differ in their empathic responses at the neural level; specifically, vegans show more intense activation of the mirror neuron motor system and brain structures linked to empathy, social cognition, and prosocial behavior (Filippi et al., 2010, 2013; Moya-Albiol et al., 2010). This distinction is relevant, as it has been established that an egalitarian attitude towards animals and humans shares empathy as the underlying factor (e.g., Braunsberger and Flamm, 2019).

Thirdly, vegans stated that their values significantly influenced their vaccination decisions more than vegetarians. Additionally, they were more likely to question the justification that animal testing of vaccines was done for a good cause and to recognize the animal suffering involved in the development of the COVID-19 vaccine. This increased awareness and the idea that experimentation is directly and strongly related to vegan concerns rather than vegetarianism may explain this difference. However, it should be noted that, as mentioned above, being vegan or vegetarian was not a good predictor of the final decision to vaccinate.

Lastly, and importantly, a higher percentage of vegans than vegetarians felt that vaccination did not align with their lifestyle or philosophy, thus explicitly acknowledging a direct conflict between their values and their attitudes and behaviors towards COVID-19 vaccination. This perception is not only reflected in the vegans’ statements but is supported by other analyses. Thus, data suggest a more significant cognitive dissonance among vegans, leading to a stronger sense of compromised values.

That said, it is remarkable that, although vegans showed more reluctance or suspicion towards vaccination than vegetarians—and despite initial reluctance towards vaccination—a large majority of vegans eventually demonstrated a high acceptance of vaccines during the health crisis. This apparent contradiction between their convictions and their actions leads to a crucial question: What were the underlying reasons that led vegans to compromise their moral values or relax their altruistic principles against animal experimentation? We propose two main factors that may have influenced this decision: (1) social stress and perceived peer pressure; and (2) the complex moral dilemmas that animal experimentation poses for its ethics.

On the one hand, social stress, and pressure, exacerbated during the pandemic, could have played an important role since it has been pointed out as a common factor in vaccination behavior in the general population, including getting vaccinated because of expectations and feelings of being “targeted” or “bullied” (Lin et al., 2022; Walsh et al., 2022). Thus, we might think that peer influence and the feeling of being judged or even bullied might have led to decisions that would not otherwise be made. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, we have seen that the debate on vegans and vaccination has been part of mainstream media during the COVID-19 crisis with consistency, unlike the one towards the veggie community. Moreover, although we observed significant differences in the consumption of information about COVID-19 in traditional media by the two groups, vegans have relied heavily on them for information about crisis-related issues, even more so than for other issues. This shows the high likelihood that vegans anticipate vegan stigma—especially with the media’s well-known speciesist bias (Khazaal and Almiron, 2016), stigmatization of animal rights advocacy (MacInnis and Hodson, 2021) and stigmatization for disrupting social conventions (Markowski and Roxburgh, 2019).

It is worth noting that COVID-19 has been starkly politicized and polarized since the beginning. In some countries, acceptance or rejection of the measures, including the progressive media, labeling vaccine dissent as sheer science denial (Bardon, 2021). Although the risk of being discriminated against for not being vaccinated was also high regardless of being vegan or not (Bor et al., 2023; Caplan, 2022; Schuessler et al., 2022), this is likely to have a more significant impact on vegans. The stigmatization of all types of dissent as anti-vax, science denial, free-riders, and misinformation (Francés et al., 2021) instead of engaging with reasonable concerns (Pruski, 2021) was a threat to critical thinking in general but likely had a higher impact on a community like vegans—already singled and stereotyped by media (Cole, 2015)—as marketing efforts for canceling the “vegan identity” in COVID-19 vaccination showed (Beverland, 2022).

Overall, the period saw unprecedented political, corporate, and media pressure on all citizens to accept the vaccine as the only solution—a pharmacological treatment that involved animal experimentation—which may have had a more significant impact on the psychology of vegans due to their willingness to avoid further stigmatization. It is well known that in times of crisis, the public and the media tend to “rally around the flag”, leading to more unreserved support for the authorities and less criticism (a term coined by Mueller, 1973; also identified for the COVID-19 crisis, Cunningham, 2020). In the case of COVID-19, the period experienced a pervasive and relatively homogeneous media and corporate representation of the crisis based on war metaphors (Chatti, 2021; Gui, 2021; Panzeri et al., 2021; Wicke and Bolognesi, 2020; Uysal and Aksak, 2022), fear and propaganda (Broudy and Hoop, 2021; Francés et al., 2021; Nwakpoke Ogbodo et al., 2020) and patriotism (Almiron et al., 2022; Basir et al., 2020) following the political authorities’ narrative (Castro Seixas, 2020; Loayssa and Petruccelli, 2022) under the intense lobbying of the pharmaceutical industry (Corporate Europe Observatory, 2021; Deruelle, 2022; Fang, 2021). All this emphasizes the imperative of vaccination and puts extraordinary pressure on the whole population, including the veg* community, especially vegans. As Park and Kim (2022) pointed out, “the pandemic certainly produced dramatic changes in vegans’ lives and sometimes even escalated tensions between vegans and nonvegans” (p. 8).

In terms of animal testing, the discursive positioning of the COVID-19 vaccine may pose a significant challenge to vegan values. Currently, there are no animal-free alternatives for many conventional drugs and medical procedures—there was none for the COVID-19 vaccines—as well as no animal-free alternative medicine in general for vegan individuals favoring options different from chemically synthesized drugs. However, this ethical challenge does not have a single or straightforward interpretation. For instance, amid the crisis, the Vegan Society reminded that the definition of veganism includes the idea that “‘it is not always possible or feasible for vegans to avoid the use of animals,” which, they added, is particularly relevant to medical situations. Furthermore, even though the vegan organization directly acknowledges that the COVID-19 vaccine is tested on animals, it defends its acceptance because “it is playing a key role in tackling the pandemic and saving lives” (“Vegan Society response to COVID-19 vaccine”, 2020). The notion that veganism is about choosing the ‘least bad’ option when it comes to animal suffering is widely understood. Similarly, the narrative promoted by PETA (2021) and The Vegan Society (2020), among others, suggests that vegans must first take care of themselves to be capable of taking care of other animals. However, this does not imply that vegans are compelled to use animal-based medicines; choosing the “least bad” option does not mean that one must always choose a bad option. They may opt out entirely, just as other members of society might. Although not rigorously studied for this movement, the ethical dilemmas posed by animal experimentation are likely one of the sources of significant controversy amongst vegans, linked to human health and a dominant biomedical paradigm that often leaves little room for alternative health models (Sheldrake, 2012; Morcan and Morcan, 2015). While vegans call for the abolition of animal experimentation, there is a broad spectrum of beliefs on what is considered acceptable practice in the interim. Peter Singer, for instance, has defended animal experimentation under limited and specified circumstances (Crawley, 2006).

Lastly, the challenges raised by animal experimentation also bring contradictions to the surface about the values vegans hold. While veganism is a philosophy of life and social movement that opposes violence towards nonhuman animals, vegans have a different rating scale for different forms of violence. The latter is reflected in our results when we asked vegans about their acceptance of animal use. We found that, compared to use in clothing, food, and entertainment, animal testing is the category least condemned by vegans.

In summary, our findings illuminate the contrasts in how vegans and vegetarians navigated the COVID-19 crisis—with vegans displaying less conformity but, ultimately, facing a profound and greater compromise of their core ethical values.

Our study has illuminated some aspects of the behavioral responses of vegetarians and vegans during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. Nevertheless, it is essential to recognize the limitations that accompany our findings and to contemplate their influence on the study’s scope and applicability. First, relying on self-reported data from questionnaires was appropriate for our focus on self-identification but may not fully capture the behavioral adherence to ethical vegan or vegetarian lifestyles. Additionally, questionnaires were distributed and collected via convenience and snowball sampling methods. While these are common approaches, they present three fundamental limitations: the sample sizes are relatively small compared to the overall veg* population, participant numbers vary by country, and the results cannot be deemed statistically representative of the entire veg* community.

Third, our approach treated ethical vegans and vegetarians as a single, unified group. Future research might be enhanced by delving into the nuances within each group. Such studies could investigate participants’ personal interpretations of veganism or vegetarianism and the duration and strictness with which they follow these lifestyles. Considering the importance of these variables in the adoption process and the construction of individual and social identity (Nezlek and Forestell, 2020; Rosenfeld and Burrow (2018), could provide valuable insights into the matter. Political ideology may also influence perspectives on vaccination and responses to the crisis, with those holding critical views of political and economic institutions (e.g., veganarchists) possibly exhibiting more negative attitudes.

Lastly, our research prompts questions that extend beyond the scope of the quantitative approach. A significant limitation lies in the complexity of ethical dilemmas, which quantitative data alone cannot fully encapsulate. Vaccination decisions are emotionally charged and imbued with moral significance, particularly for individuals committed to animal advocacy. This study has primarily taken a cognitivist approach, focusing on rational variables. However, the subtleties of ethical decision-making—such as how individuals reconcile their values with the choice to vaccinate—represent a complex landscape that our methods could not thoroughly investigate. Moreover, the delicate equilibrium between public health imperatives and personal ethical beliefs has posed a moral quandary for many, prompting a spectrum of responses influenced by ethical, emotional, and social factors. While comprehensive, our study may not have captured the full intricacy of the veg* community’s response to the crisis, including the roles of individual rationalizations. Future research would thus benefit from qualitative methodologies that delve into the psychological, social, and moral terrains navigated by vegans in decision-making processes. In-depth interviews could illuminate the internal conflicts and justifications surrounding vaccination decisions. Narrative analysis might also reveal how vegans and vegetarians construct their identities and make health-related decisions amidst societal pressures and ethical dilemmas. Adopting a qualitative perspective would complement our findings and provide a richer understanding of the lived experiences of vegetarians and vegans during this unparalleled global health crisis. Moreover, pursuing these lines of inquiry would contribute to the broader discourse on how vegetarians and vegans manage contradictions in a non-vegan world, an area of interest that has been notably explored by other authors (e.g., Greenebaum, 2012).

Conclusion

The veg* community encountered significant challenges to their values during COVID-19, particularly regarding vaccination decisions. With the vaccine—a product based on animal experimentation—presented as the sole solution to end the crisis and promoted by government authorities and the media, these individuals faced profound ethical decisions. This exploratory research has presented findings that compare the responses of ethical vegans and vegetarians to the vaccination challenge. Our results indicate that the veg* community is diverse, with vegans exhibiting the least conformist attitudes and behaviors towards the pandemic management measures. Nonetheless, the findings also reveal that despite their critical stance and their aim to protect vulnerable populations, the vegan community has largely compromised their moral values by accepting the vaccine. This research enhances the expanding field of veg* studies and animal rights literature by exploring how a health crisis impacts the behaviors and perspectives of ethical vegetarians and vegans. Our study also contributes to shed light on the challenges and biases that a minority group, such as vegans, may face and how they cope with the pressure to go against the mainstream at a time when society is polarized by a single possible discourse that goes against its moral values.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

In this paper, the term veg* will be used to include both vegetarian and vegan options.

In this paper, we use non-speciesist language, that is, we avoid using language that commodifies and objectifies nonhuman animals-like singular words used for collectives and thus hiding the individuals in them (fish, sheep, etc.).

For instance, Akhtar (2012a, 2012b) revealed that only 8% of new compounds passing preclinical tests (where animal experimentation is involved) reach the market. The 92% failing to make it to the market proved to be ineffective and/or unsafe in humans. This leads this and other authors to define animal experimentation not only as unethical but also as unreliable and unnecessary.

From January 2023, the US Food and Drugs Administration no longer needs to require animal testing before human trials of drugs (Wadman, 2023). https://www.science.org/content/article/fda-no-longer-needs-require-animal-tests-human-drug-trials.

References

Akhtar A (2012a) The costs of animal experiments. In: Akhtar A (ed) Animals and public health. The Palgrave Macmillan animal ethics series. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Akhtar A (2012b) Animals and public health. In: Akhtar A (ed) Why treating animals better is critical to human welfare. The Palgrave Macmillan animal ethics series. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Akhtar A (2015) The flaws and human harms of animal experimentation. Camb Q Healthc Eth 24(4):407–419. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963180115000079

Almiron N, Thornton G, Martins G (2022) The media’s forgotten animal link: species-patriotism in world press coverage of COVID-19. Anim Eth Rev 2(1):60–77

Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act 2022 (2022) Government Bill. Originated in the House of Lords, Session 2021–22. https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/2867

Bardon A (2021) Political orientation predicts science denial—here’s what that means for getting Americans vaccinated against COVID-19. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/political-orientation-predicts-science-denial-heres-what-that-means-for-getting-americans-vaccinated-against-COVID-19-165386

Basir SN, Bakar MZ, Ismail F, Hassan J (2020) Conceptualizing on structure functionalism and its applications on patriotism study during COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. South Asian J Soc Stud Econ 6(4):1–7. https://doi.org/10.9734/sajsse/2020/v6i430171

BBC (2020) Ethical veganism is philosophical belief, tribunal rules. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-50981359

Beardsworth A, Keil ET (1991) Vegetarianism, veganism, and meat avoidance: recent trends and findings. Br Food J 93(4):19–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070709110135231

Beardsworth A, Bryman A (1999) Meat consumption and vegetarianism among young adults in the UK: an empirical study. Br Food J 101(4):289–300. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070709910272169

Berry E (2020) Pets: the voiceless victims of the COVID-19 crisis. Phys.org. https://phys.org/news/2020-03-pets-voiceless-victims-covid-crisis.html

Beverland M (2022) Vegans and vaccines: a tale of competing identity goals. NIM Mark Intell Rev 14(1):31–35. https://doi.org/10.2478/nimmir-2022-0005

Bittel J (2020) Experts urge people all over the world to stop killing bats out of fears of coronavirus. NRDC. https://www.nrdc.org/stories/experts-urge-people-all-over-world-stop-killing-bats-out-fears-coronavirus

Blattner CE (2019) The recognition of animal sentience by the law. J Anim Eth 9(2):121–136. https://doi.org/10.5406/janimalethics.9.2.0121

Bor A, Jørgensen F, Petersen MB (2023) Discriminatory attitudes against unvaccinated people during the pandemic. Nature 613:704–711. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05607-y

Bramble B (2021) Are COVID vaccines vegan? Should I get one anyway? An ethicist explains. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/are-covid-vaccines-vegan-should-i-get-one-anyway-an-ethicist-explains-155221

Braunsberger K, Flamm RO (2019) The case of the ethical vegan: motivations matter when researching dietary and lifestyle choices. J Manag Issues 228–245. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45206622

Broudy D, Hoop D (2021) Messianic mad men, medicine, and the media war on empirical reality. Int J Vaccine Theory Pract Res 2:1. https://doi.org/10.56098/ijvtpr.v2i1.22

Caplan AL (2022) Stigma, vaccination, and moral accountability. The Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00189-1

Castro Seixas E (2020) War metaphors in political communication on COVID-19. Front. Sociol. 5, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.583680

Catalunya Press (2021) Un vegano que no se vacunó por estar en contra de las pruebas con animales fallece por Covid-19 a los 54 años. Catalunyapress. https://www.catalunyapress.es/texto-diario/mostrar/3325605/vegano-no-vacuno-estar-contra-pruebas-animales-fallece-covid-19-54-anos

Chatti S (2021) Military framing of health threats: the COVID-19 Disease as a case study. Language Discourse Soc 9(17):33–44. 1 https://bibliotekanauki.pl/articles/2081289.pdf

Cochrane A, Cojocaru MD (2022) Veganism as political solidarity: beyond ‘ethical veganism. J Soc Philos 54(1):59–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/josp.12460

Cole M, Morgan K (2011) Vegaphobia: derogatory discourses of veganism and the reproduction of speciesism in UK national newspapers. Br J Sociol 62(1):134–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2010.01348.x

Cole M (2015) Getting (green) beef: anti-vegan rhetoric and the legitimizing of eco-friendly oppression. In: Critical animal and media studies. Routledge

Corporate Europe Observatory (2021) Big Pharma’s lobbying firepower in Brussels: at least €36 million a year (and likely far more). https://corporateeurope.org/en/2021/05/big-pharmas-lobbying-firepower-brussels-least-eu36-million-year-and-likely-far-more

COVID-19 Vaccines and Veganism (2021) Animal aid. https://www.animalaid.org.uk/COVID-19-vaccines-and-veganism/

Crawley W (2006) Peter Singer defends animal experimentation. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/ni/2006/11/peter_singer_defends_animal_ex.html

Cunningham K (2020) The rally-round-the-flag effect and COVID-19. UK in a Changing Europe. https://ukandeu.ac.uk/the-rally-round-the-flag-effect-and-COVID-19/

Davis G (2021) COVID-19 vaccines: my message to vegans. https://chanapdavis.medium.com/COVID-19-vaccines-my-message-to-vegans-e37cab34f503

Deruelle F (2022) The pharmaceutical industry is dangerous to health. Further proof with COVID-19. Surg Neurol Int 13. https://doi.org/10.25259/SNI_377_2022

De la Paz J (2021) ¿Son veganas las vacunas contra la covid? Vitamina Vegana. https://www.vitaminavegana.com/son-veganas-las-vacunas-contra-la-covid/

Díaz EM (2012) Perfil del vegano/a activista de liberación animal en España. Rev Esp Investig Sociol 3(139):175–188. https://doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.139.175

Díaz EM(2016) Animal humanness, animal use, and intention to become ethical vegetarian or ethical vegan Anthrozoös 29(2):263–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2016.1152720

Díaz EM (2017a) Predictive ethical consumption: the influences of gender in the intention of adopting ethical veganism. J Consum Eth 1(2):100–110

Díaz EM (2017b) The second-curve model: a promising framework for ethical consumption? Veganism as a case study. In: Bala C, Müller K (eds) The vulnerable consumer: the social policy dimension of consumer policy. International Conference on Consumer Research (ICCR)

Díaz EM (2018) Emerging attitudes towards nonhuman animals among Spanish University students. Soc Anim 1(1):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-12341490

Díaz EM, Horta Ó (2020) Defending equality for animals: the antispeciesist movement in Spain and the Spanish-speaking world. In: Carretero M (ed) Spanish thinking about animal. Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, MI

Dickstein J, Dutkiewicz J, Guha-Majumdar J, Winter DR (2022) Veganism as left praxis. Cap Nat Soc 33(3):56–75. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10455752.2020.1837895

Dinh NHA, Siegfried P (2023) Investigation of the impact of vegetarianism and veganism on the post-COVID-19 gastronomy and food industry. Int J Food Syst Dyn 14(3):351–361. https://doi.org/10.18461/ijfsd.v14i3.G8

Enerio D (2021) Vegan who rejected COVID-19 vaccine over animal testing dies of virus. Int Bus Times. https://www.ibtimes.com/vegan-who-rejected-COVID-19-vaccine-over-animal-testing-dies-virus-3347130

Esselstyn Family Foundation (2021) https://www.facebook.com/101291804548430/posts/dr-e-getting-his-covid-vaccine-shot-today-at-the-cleveland-clinic-we-urge-you-al/432122008132073

Facts and Figures on Animal Testing (n.d.) Cruelty Free International. https://crueltyfreeinternational.org/about-animal-testing/facts-and-figures-animal-testing

Fang L (2021) Pharmaceutical industry dispatches army of lobbyists to block generic covid-19 vaccines. The Intercept_. https://theintercept.com/2021/04/23/covid-vaccine-ip-waiver-lobbying/

Feng E (2021) Health workers in China are killing pets while their owners are in quarantine. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/11/15/1055831581/health-workers-in-china-are-killing-pets-while-their-owners-are-in-quarantine

Filippi M, Riccitelli G, Falini A, Salle F, Vuilleumier P, Comi G, Rocca MA (2010) The brain functional networks associated to human and animal suffering differ among omnivores, vegetarians, and vegans. PLoS ONE5:e10847. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010847

Filippi M, Riccitelli G, Meani A, Falini A, Comi G, Rocca MA (2013) The “vegetarian brain”: chatting with monkeys and pigs? Brain Struct Funct 218(5):1211–1227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-012-0455-9

Fox N, Ward K (2008) Health, ethics and environment: a qualitative study of vegetarian motivations. Appetite 50(2):422–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.09.007

Francés P, Loayssa JR, Petruccelli A (2021) Covid 19 La respuesta autoritaria y la estrategia del miedo. Ediciones el Salmon

Francione GL (2020) Do vegans who get a COVID-19 vaccine abandon their moral principles? Yes—and no. Medium. https://medium.com/curious/do-vegans-who-get-a-COVID-19-vaccine-abandon-their-moral-principles-yes-and-no-f631a3a922f

Gerdts V, Littel-van den Hurk SVD, Griebel PJ, Babiuk LA (2007) Use of animal models in the development of human vaccines. Future Microbiol 2(6):667–675. https://doi.org/10.2217/17460913.2.6.667

Giraud EH (2021) Veganism. Politics, practice and theory. Bloomsbury. https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/veganism-9781350124936/

Greenebaum J (2012) Veganism, identity and the quest for authenticity. Food Cult Soc 15(1):129–144. https://pubag.nal.usda.gov/catalog/6915098

Guerrini A (2022) Experimenting with humans and animals: from Aristotle to CRISPR. Johns Hopkins University Press

Gui L (2021) Media framing of fighting COVID-19 in China. Sociol Health Illn 43(4):966–970. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13271

Hargreaves SM, Raposo A, Saraiva A, Zandonadi RP (2021) Vegetarian diet: an overview through the perspective of quality of life domains. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(8):4067, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8069426/

Harris P (2021) La consagración del animal en el derecho constitucional comparado. Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. Asesoría Técnica Parlamentaria. No. SUP: 131693

Haworth J (2020) 8 big cats confirmed tested positive for coronavirus at NY zoo. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/big-cats-test-positive-COVID-19-zookeeper-accidentally/story?id=70303070

Herrmann K, Jayne K (2019) Animal experimentation: working towards a paradigm change. Brill. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvjhzq0f

Herzog H (2022). Vaccinations, vegans, and the problem of moral consistency when it comes to vaccines, consistency is an overrated moral principle. Psychol Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/animals-and-us/202207/vaccinations-vegans-and-the-problem-moral-consistency

Hoffman SR, Stallings SF, Bessinger RC, Brooks GT (2013) Differences between health and ethical vegetarians. Strength of conviction, nutrition knowledge, dietary restriction, and duration of adherence. Appetite 65:139–144

Hopwood CJ, Bleidorn W, Schwaba T, Chen S (2020) Health, environmental, and animal rights motives for vegetarian eating. PLoS ONE 15(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230609

Horta O (2018) Discrimination against vegans. Res Publica 24(3):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11158-017-9356-3

Horta O, Cancino-Rodezno A (2022) Experimentación con animales: un examen de los argumentos en su defensa. Crítica 54(161):71–94. https://doi.org/10.22201/iifs.18704905e.2022.1349

How Flu Vaccines are Made (n.a.) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/how-fluvaccine-made.htm

Jabs J, Sobal J, Devine CM (2000) Managing vegetarianism: identities, norms and interactions. Ecol Food Nutr 39(5):375–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2000.9991625

Janda S, Trocchia PJ (2001) Vegetarianism: toward a greater understanding. Psychol Mark 18(12):1205–1240. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.1050

Janssen M, Busch C, Rödiger M, Hamm U (2016) Motives of consumers following a vegan diet and their attitudes towards animal agriculture. Appetite 105:643–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.06.039

Judge M, Wilson MS (2019) A dual‐process motivational model of attitudes towards vegetarians and vegans. Eur J Soc Psychol 49(1):169–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2386

Kalof L, Dietz T, Stern PC, Guagnano GA (1999) Social psychological and structural influences on vegetarian beliefs. Rural Sociol 64(3):500–511. Kalof, (1999)

Kalte D (2020) Political veganism: an empirical analysis of vegans’ motives, aims, and political engagement. Political Stud 69(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/003232172093017

Kassam A, Grover N (2021) Animal testing suspended at Spanish lab after ‘gratuitous cruelty’ footage. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/apr/12/animal-testing-suspended-at-spanish-lab-after-gratuitous-cruelty-footage

Kesslen B (2020) Here’s why Denmark culled 17 million minks and now plans to dig up their buried bodies. The Covid mink crisis, explained. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/animal-news/here-s-why-denmark-culled-17-million-minks-now-plans-n1249610