Abstract

Young adults today face greater financial difficulties than previous generations as they transition from financial dependence to financial independence and require sufficient financial capabilities to overcome financial setbacks. Few studies, however, have conducted a detailed analysis of the literature on young adults’ financial capabilities in the Asia-Pacific region, home to over 1.1 billion young adults, and the US. Thus, this study systematically reviewed the literature addressing the factors affecting young adults’ financial capabilities in the US and the Asia-Pacific region, in accordance with the RepOrting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses (ROSES) publication standard and employing multiple research designs. The articles for this study were selected from two authoritative databases, Scopus and Web of Science, and a supplementary database, Google Scholar. Twenty-four articles were included for quality appraisal and qualitative synthesis based on predetermined criteria, including articles with empirical evidence published in English, with the US and Asia-Pacific countries as context and published after 2006. This review was divided into six major themes: (1) financial knowledge/literacy and education, (2) financial behaviour, (3) financial attitude, (4) financial inclusion, (5) financial socialisation, and (6) demographic characteristics. Eleven sub-themes were developed from the six major themes. The findings of this review identify three approaches to enhance the financial capability of young adults: (1) early financial education with practical simulations, which can promote positive financial attitudes and healthy financial behaviour; (2) assisting parents with adequate financial education given their role as the primary financial socialisation agents for young adults; and (3) coupling financial education with access to formal financial institutions. Additionally, this study provides insight into the directions that should be taken by future research endeavours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Young adults are expected to become financially independent during the transitional years of young adulthood, lasting from ages 18–26, through their engagements in romantic relationships, becoming parents, and taking on responsible duties as productive members of society during the transitional years of young adulthood (Bonnie and Stroud, 2015). Previous studies have shown that a growing number of young adults aged between 18 and 29 are having financial difficulties (Brüggen et al., 2017; Williams and Oumlil, 2015). Their problems can be attributed to their shift from financial dependency to financial independence (Gutter and Copur, 2011; Sorgente and Lanz, 2017). Growing student debt (Brüggen et al., 2017; Elliott and Lewis, 2015; Shim et al., 2009; Williams and Oumlil, 2015), lack of adequate information to make critical financial decisions (Lusardi et al., 2010; O’Connor et al., 2019; Williams and Oumlil, 2015), and low financial literacy, which would negatively influence their savings rate (Ergün, 2018), may all contribute to these difficulties. The 2018 National Financial Capability Study conducted in the US painted a disturbing picture, finding that younger Americans have had a lower rate of growth in their ability to cover monthly expenses and bills compared to other age groups (Lin et al., 2019). The study also reported that a large number of Americans, primarily young adults aged 18–34, thought that personal finance was their primary source of anxiety and most students with college debt felt worried that they would not be able to pay off their student loans.

According to a recent OECD survey, vulnerable populations in the Asia-Pacific, such as micro, small, and medium enterprises, migrants and their families, women, and young people, have suffered a greater impact from the global economic downturn resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2021). Vulnerable groups had lower savings, more difficulties making ends meet, no financial cushion to handle unforeseen deficits, increased financial stress, and a higher likelihood of being victims of financial fraud.

Approximately 1.1 billion young people aged 15–29 live in Asia and the Pacific region, representing 60% of young people globally, making the Asia-Pacific the most youthful area (Morris, 2019). According to recent data from the US, the total number of young adults aged 15–29 was 65.47 million (STATISTA, 2021). Young adults in the US and Asia-Pacific region face similar financial difficulties transitioning from financial dependence to financial independence. In the US, young American adults find it difficult to buy a house, save for the future, and pay for college (Sechopoulos, 2022), indicating that financial capability is still out of reach for many. A survey on financial literacy in Asia revealed that South Asia has some of the lowest financial literacy scores, as only a quarter of adults are financially literate (Xiao, 2020). The conditions faced by young adults in these regions underscore the importance of enhancing the financial capability of young adults to make sound financial decisions.

Given the growing need for sound financial decision-making due to today’s consumer financial challenges, assessing individuals’ financial capabilities, particularly in young adults, has become critical. Achieving financial capability is a crucial developmental challenge for this population (Arnett, 2000), and young adults must have excellent financial capabilities early on to achieve financial success (Sherraden and Grinstein-Weiss, 2015).

Financial capability is a multidimensional concept incorporating many behavioural facets related to how individuals handle their resources and make financial decisions. According to Sherraden (2013), financial capability is a concept that bridges economics, psychology, and sociology, combining a person’s ability to act with their opportunity to act. Other scholars also defined financial capability as a combined skill, describing it as a combination of financial literacy and financial behaviour to achieve financial well-being (Xiao, 2016). Financial capability is a mixture of the financial knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviours required to make sound financial decisions based on personal circumstances, to improve financial well-being (Muir et al., 2017). Another definition states that financial capability includes individuals’ knowledge, ability to understand their financial circumstances, and motivation to take action (HM Treasury, 2007).

Scholars have long been interested in the financial capabilities of young adults and have used a variety of perspectives to analyse the topic (Cheak-Zamora et al., 2017; Mottola, 2014; Nam and Loibl, 2020; Ranta and Salmela-Aro, 2018; Serido et al., 2013; Taylor, 2011; West and Friedline, 2016; Williams and Oumlil, 2015; Winstanley et al., 2018; Xiao et al., 2015). In 2005, researchers under the UK Financial Service Authority began to study consumers’ financial capability, completing a national financial capability survey in 2006 (Xiao et al., 2022). Other developed countries, such as the US, Canada, and Japan, have followed the UK’s lead in examining financial capability among consumers. However, most studies on the financial capabilities of young adults are done in the US. Although many studies have focused on young adults’ financial capabilities, a systematic review of past studies is required because of its numerous benefits over traditional reviews, such as the use of a precise question to generate evidence to underpin a piece of research, several specific databases using accurate search terms, data extraction tools to identify exact pieces of information, and a data presentation methodology (Robinson and Lowe 2015).

This study aims to add to the current body of knowledge by conducting a systematic literature review on the factors contributing to the development of young adults’ financial capabilities, explaining the differences between financial capability determinants in the US and the Asia-Pacific region. This review is guided by a central research question—What factors contribute to young adults’ financial capabilities in the US and Asia-Pacific region?

According to Shaffril et al. (2020), a systematic literature review entails classifying, selecting, and critically evaluating previous studies through an organised and transparent process that utilises multiple databases. This type of review employs a rigorous search strategy to explain a pre-defined question (Xiao and Watson, 2019). The approach has been widely utilised by a large number of researchers. Although some studies have conducted systematic reviews of young adults’ financial issues, the emphasis has not been on financial capability but on financial well-being (Sorgente and Lanz, 2017). Existing literature reviews on financial issues tend to focus on other or broader segments of the population rather than young adults specifically, such as women’s financial planning and financial well-being (Gonçalves et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2019), consumers’ financial well-being (Nanda and Banerjee, 2021), and individuals’ personal financial management behaviour (Goyal et al., 2021).

Despite the growing interest and valuable insights provided by previous systematic literature review studies, there is still a dearth of systematic reviews on young adults’ financial capabilities. To the best of our knowledge, no study has comprehensively reviewed young adults’ financial capabilities, particularly in the US and Asia-Pacific region. This study makes significant conceptual contributions by elucidating the factors influencing young adults’ financial capabilities. This study will assist interested parties such as policymakers, the public, and researchers in enhancing young adults’ financial capabilities.

Methodology

Review protocol

This study was guided by the RepOrting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses (ROSES) review protocol. According to Haddaway et al. (2018), the overall goal of the ROSES protocol is to increase and sustain high standards in conducting systematic reviews and maps through increased transparency and to facilitate quality assurance. Although initially designed for transparent reporting in environmental management and conservation, there is no restriction on the application or adaptation of ROSES across other fields. Haddaway et al. (2018) have asserted that ROSES requires a higher standard of conduct for evidence synthesis than other reporting standards, reduces the emphasis on quantitative synthesis (recognising the value of other methods), and allows for many different types of synthesis. In comparison to existing reporting guidance (e.g., PRISMA), ROSES combines reporting with methodological advice and, thus, highlights ‘gold standard’ methods to support the production of higher quality protocols and reviews. The protocol provides detailed and precise instructions with examples for all stages of the review process including planning, conducting, and reporting (Haddaway et al., 2018).

This systematic literature review began with the formulation of a research question to be reviewed in the first step. The systematic search strategy was divided into three distinct subprocesses: identification, screening (inclusion and exclusion criteria), and eligibility. The authors then evaluated the quality of the selected articles based on predetermined parameters. Finally, the data for the review were abstracted, analysed, and validated.

Formulation of the research question

The research question development tool used to formulate the research question was PICo, standing for population, phenomena of interest, and context. PICo is used to guide the development of a clear and meaningful research question (Lockwood et al., 2015). Based on this concept, the authors included three main aspects in the review—young adults (population), financial capability determinants (interest), and the US and Asia-Pacific (context)—leading to the formulation of the primary research question: What factors contribute to young adults’ financial capabilities in the US and Asia-Pacific region?

Systematic search strategies

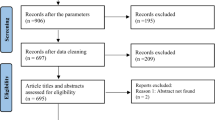

Three processes are involved in systematic search strategies: identification, screening, and eligibility (Fig. 1).

Identification

During the identification stage, synonyms, related terms, and variations of the study’s primary keywords, ‘financial capability’ and ‘young adults’, were identified. This process increased the number of keyword variations that could be used to search the selected databases for additional related articles. This stage relied on an online thesaurus, keywords used in previous studies, and keywords suggested by Scopus or authors. The keywords were enhanced using Boolean operators, phrase searching, truncation, wild card, and field code functions, as suggested by Shaffril et al. (2020). The search strings used are provided in Table 1 in their entirety.

This study used the Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases. The first two databases, Web of Science and Scopus, were the leading databases, while Google Scholar was used as a supporting database. Web of Science and Scopus are the world leaders in academic databases (Zhu and Liu, 2020), offering several advantages, including an advanced search function, comprehensiveness (indexing more than 5000 publishers), and quality control articles (Gusenbauer and Haddaway, 2020). The use of Google Scholar as a supporting database is in line with Haddaway et al. (2015), who explained that while Google Scholar could uncover a great number of grey literature and specific, known studies, it should not be used exclusively for systematic review searches. A combination of keywords used in the Web of Science and Scopus databases was also applied to Google Scholar. The search process in these three databases resulted in a total of 295 articles identified (Fig. 1).

Screening

Using the sorting function available in the databases, 294 articles were identified for the screening phase. Several criteria were used to select articles during the screening stage. The number of studies examining young adults’ financial capabilities was found to have increased significantly since year 2007. Furthermore, only articles with empirical evidence published in peer-reviewed journals were included to ensure quality. Articles also had to be published in English and use the US and Asia-Pacific countries as their context. This procedure resulted in the removal of 43 duplicate articles and 125 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. The eligibility of the remaining 126 studies was assessed in the third step.

Eligibility

The authors manually reviewed the article titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles to ensure that all remaining articles (after screening) meet the eligibility requirements. This process eliminated 102 articles that emphasised financial literacy, financial knowledge, financial behaviour, financial socialisation, financial well-being, or other variables rather than financial capability or that did not focus on young adults. Twenty-four articles remained for quality appraisal and qualitative synthesis. A summary of all the systematic search strategies is presented in Fig. 1.

Quality appraisal

A quality appraisal was conducted to determine whether the study adequately answered the questions in a systematic review. The remaining articles were presented to experts for a quality assessment. The primary goals of the quality assessment were to evaluate and select studies that addressed the research questions and provide evidence for a more in-depth analysis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The authors evaluated quality based on several criteria adapted from the quality appraisal questions of Alsolai and Roper (2019) and Shaffril et al. (2021). Questions such as ‘Does the study describe the primary research objective?’, ‘Does the study define financial capability?’, ‘Does the study determine financial capability measurement?’, ‘Does the study state financial capability determinants?’, and ‘Does the study define young adults clearly?’ were included. The 12 questions were scored as Yes (1 point), Partly (0.5 point), and No (0 point).

The papers were classified into four categories based on their overall score: excellent (10 ≤ score ≤ 12), good (6.5 ≤ score ≤ 9.5), fair (3 ≤ score ≤ 6), and fail (0 ≤ score ≤ 2.5). By applying the above criteria, twelve papers were categorised as ‘excellent’, ten papers were ‘good’, and two papers were ‘fair’. None of the identified papers failed the quality assessment, meaning 24 studies were included in the systematic literature review (see Table 2).

Data extraction and analysis

The data extraction process is guided by the identified research question. In this phase, any data that can assist the researchers in answering the research question should be extracted (Shaffril et al., 2020). In the present review, three researchers independently performed the data extraction process to minimise data compilation errors, as suggested by Charrois (2015).

This study utilised an integrative review, allowing for the incorporation of various research designs (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods). The most effective method for synthesising or analysing integrative data is to employ qualitative or mixed-method techniques that enable iterative comparisons across primary data sources (Whittemore and Knafl, 2005), so a qualitative technique was used in this study. The researchers read the 24 articles carefully, paying special attention to the abstracts, results, and discussion sections. Data were extracted from reviewed studies that addressed the research question and organised in a table.

Thematic analysis is well-suited for synthesising integrative studies (Flemming et al., 2019) and is highly adaptable (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The process of thematic analysis began with the development of themes. Throughout this process, the authors sought to identify patterns that emerged from the abstracted data of all reviewed articles. Any abstracted data that were similar or related were grouped together. After re-examining the six data groups formed, the authors identified an additional 11 subgroups. The authors then re-examined the data’s major themes and sub-themes to ensure their utility and accuracy. The final patterns contained six major and 11 minor themes following this process. The authors then assigned themes to each group and its subgroups, as illustrated in Table 3.

Throughout the theme development phase, the corresponding and co-authors discussed any inconsistencies, thoughts, puzzles, or ideas regarding the data interpretation until an agreement was reached on how to adjust the developed themes and sub-themes. Two panel experts in qualitative techniques and behavioural finance evaluated the six developed themes and eleven sub-themes, and both agreed on the proposed themes and sub-themes. As presented in Table 3, the six themes are (1) financial knowledge/financial literacy and financial education, (2) financial behaviour (five sub-themes), (3) financial attitude, (4) financial inclusion, (5) financial socialisation (two sub-themes), and (6) demographic characteristics (four sub-themes).

Results

Background of selected articles

Six themes emerged from the thematic analysis of the 24 selected articles: (1) financial knowledge/financial literacy and education, (2) financial behaviour, (3) financial attitude, (4) financial inclusion, (5) financial socialisation, and (6) demographic characteristics. Further analysis of these themes identified 11 sub-themes. Eighteen of the 24 studies were conducted in the United States, three in Hong Kong, and one each in Pakistan, Thailand, and New Zealand. Out of 24 selected articles, one was published in 2007, one in 2013, four in 2015, two in 2016, two in 2017, three in 2018, three in 2019, four in 2020, and three in 2021.

Seventeen studies focused on quantitative analysis, while three focused on qualitative analysis, two studies employed a mixed-method approach, and two were conceptual papers. All of the papers were related to the financial capabilities of young adults, though the age range defined as ‘young adults’ varied. Most of the papers (12 papers) focused on young adults aged 18 and older, while a few focused on children below 12 years old (2 papers) and adolescents 12–18 years old (3 papers) (see Table 3).

Themes and sub-themes

Financial knowledge/financial literacy and financial education

Thirteen of the 24 studies focused on how financial knowledge/literacy and financial education shape young adults’ financial capabilities. The financial capability of young people develops with the acquisition of financial knowledge and literacy through financial education, whether inclusive or not, making financial education critically important (Friedline and West, 2016; Johnson and Sherraden, 2007; Sherraden et al., 2011; Sherraden and Grinstein-Weiss, 2015; West and Friedline, 2016). It improves young people’s understanding of financial concepts (Eichelberger et al., 2017) and their performance in financial capability assessments (Noreen et al., 2019). Additionally, young people have expressed concern about their lack of financial management skills and their desire for additional education (Cheak-Zamora et al., 2017).

One study found that young adults who participated in a financial education workshop experienced a significant increase in their financial knowledge (Loke et al., 2015). Furthermore, underrepresented youth admitted that without financial knowledge and experience, they could not identify or utilise the resources on campus without the assistance of a mentor (Eichelberger et al., 2017). Financial knowledge and other factors are also part of a dynamic process of learning to make financial decisions and affect how these decisions impact transitions into adulthood (Serido et al., 2013).

Financial behaviour

Financial behaviour is often featured in the study of factors shaping young adults’ financial capability. Under this theme, five sub-themes also emerged. The first is desirable financial behaviour. A study conducted in New Zealand that composed an index of financial capability in young adults discovered that desirable financial behaviour had a significant positive effect (Czar et al., 2021). Desirable financial behaviours were also found to be required to accurately measure and index financial capability in a study in the US (Xiao et al., 2015, 2020).

Consistently, young people’s financial capabilities are substantially related to healthy financial behaviours (Friedline and West, 2016). Changing young adults’ financial behaviours is also associated with changes in their financial capabilities and well-being (Serido et al., 2013). In similar results to previous research, studies conducted in Pakistan and Hong Kong discovered that young adults could internalise both their subjective and objective financial knowledge to engage in healthy financial behaviour (Noreen et al., 2019; Zhu and Chou, 2018). Participation in a savings programme, which is considered desirable financial behaviour, may also enhance financial capability. A financial capability programme called MyPath Savings effectively increased vulnerable youth’s financial capability in the United States, assisting them in developing good financial practices and saving habits as they grow older (Loke et al., 2015). Young adults who received allowances as children reported a modestly higher level of financial responsibility, implying that allowances for children and teenagers may complement other financial capability development strategies for young people (Collins and Odders-White, 2021). Huang et al. (2015) discovered a positive correlation between financial capability and parents’ likelihood of opening college savings accounts for their children.

Advice-seeking financial behaviour is the second sub-theme under financial behaviour. In the United States, the perceived financial capability of young adults is positively linked with advice-seeking financial behaviour and short-term and long-term financial behaviour, or the third and fourth sub-themes of this theme (Fan, 2021).

The final sub-theme is avoiding risky financial behaviour. In the United States, financial capability among low-income young people who do not use alternative financial services is associated with avoiding risky financial behaviour and practising healthy behaviours (West and Friedline, 2016).

Financial attitude

The second theme is financial attitude. Several previous studies have found that financial attitudes play a vital role in shaping the financial capabilities of young adults (Loke et al., 2015; Noreen et al., 2019). A positive change in financial attitudes was identified among young adults in the United States who participated in financial capability programmes (Loke et al., 2015). Young adults who received financial education also had positive financial attitudes and performed better on financial capability measurements (Noreen et al., 2019). A cross-generational study conducted in Thailand by Amonhaemon and Vora-Sitta (2020) confirmed that financial literacy influences financial attitudes for all generations (baby boomers, Gen X, and Gen Y/Millennials), though different approaches need to be implemented to encourage each generation to have rational financial capabilities.

Financial inclusion

Several studies conducted in the United States have examined young adults’ financial inclusion and its relationship with their financial capabilities, establishing a link between bank account ownership and financial capabilities. The combination of a savings account and financial education can promote healthy financial behaviour in young adults and improve their financial capabilities (Friedline and West, 2016). Additionally, financial capability has been found to be positively associated with the likelihood of maintaining a college savings account (Huang et al., 2015). Johnson and Sherraden (2007) suggested that financial education should include access to financial institutions, possibly through saving incentives to develop financial capability. They believe that a combination of financial education, institutional access, and opportunities for saving accumulation is more effective in boosting young adults’ financial capabilities. The financial capability of young adults also expands when they have access to financial education and participate in meaningful financial services, such as school-based financial education and savings programmes (Sherraden et al., 2011).

Financial socialisation

Family financial socialisation was found to affect young adults’ financial capabilities in three studies conducted in the United States and one in Hong Kong (LeBaron et al., 2018; Salazar et al., 2021; Sherraden et al., 2011; Sherraden and Grinstein-Weiss, 2015; Zhu, 2018). Under this theme, two sub-themes emerged: financial socialisation from the family and financial socialisation from caseworkers. Financial socialisation from caseworkers was less common in this review. According to a study conducted in the United States, youth in foster care were more likely to ask questions about financial matters to caring adults, and youth with permanent adults in their lives are more likely to be financially capable (Salazar et al., 2021).

Financial socialisation from the family was frequently used to study young adults’ financial issues. LeBaron et al. (2018) conducted a qualitative study as part of the ‘What’s and How’s of Family Financial Socialisation’ project, collecting the perspectives of 126 undergraduate students regarding how and what they intend to teach their future children about finances. Participants were enroled in family finance classes at three institutions located in three distinct regions of the United States. This project generated four themes: communicating family finances, opportunity for responsibility, the value of hard work, and the process of saving. The first two themes concern how to effectively teach their children, while the final two reflect what they intend to teach their children.

Sherraden and Grinstein-Weiss (2015) identified three trends emphasising the critical nature of early financial capability development. Young adults face increasing complexity in daily financial decision-making, confront high-stakes financial decisions earlier in life than a generation ago, and struggle financially. Additionally, the study focused on young adults’ capacity to lay a foundation for learning about and applying financial concepts, highlighting the critical role of family financial socialisation. Parents play an important role in introducing financial-related matters to their children, and parental socialisation has been found to influence healthy financial behaviour among Chinese adolescents (Zhu, 2018).

Demographic characteristics

Four sub-themes were identified within the demographic characteristics theme, the first of which is income. The relationship between adolescent family income and young adult financial independence in the United States makes inverted U-shaped, with the peak in the 30th percentile of family income. This finding suggests that family income during adolescence has a positive effect on young adults’ financial independence to a point, before the effect becomes negative (Cui et al., 2019). Additionally, young adults in the United States perceived a potential lack of income as a barrier to independence that exposed them to additional risks (Cheak-Zamora et al., 2017).

Education level is the second demographic characteristics sub-theme. Young adults in the United States who completed university had an approximately greater possibility of financial independence than those who did not graduate from university (Cui et al., 2019). Young adults with a university degree also scored higher on indicators of objective and subjective financial knowledge, desirable financial behaviour, and the perceived financial capability index when compared to young adults who dropped out of university (Xiao et al., 2020).

The third identified sub-theme is residential status. Young adults who left their parents’ homes (home leavers) experienced a significant increase in the financial capability index (Czar et al., 2021). Age is another factor influencing young adults’ financial capabilities. A study was conducted in the United States concluded that older foster-care youth (over 18 years) had more advanced financial capabilities than younger youth in foster care (Salazar et al., 2021). Additionally, older youth in the United States demonstrated a higher level of both objective and subjective financial literacy, perceived financial capability, and overall financial capability than their younger counterparts (Xiao et al., 2015). A Thai study found that more youthful and single youth lacked financial capability compared to older couples (Amonhaemanon and Vora-Sitta, 2020).

Discussion

The six themes identified in the thematic analysis are discussed in greater detail in the following sub-sections, comparing the conditions in the US and the Asia-Pacific region for the themes found in the two regions.

Financial knowledge/literacy and financial education

The terms financial knowledge and financial literacy are often used interchangeably, however, financial knowledge is actually a sub-component of financial literacy along with financial awareness, behaviour, attitude (OECD INFE, 2011). Consistent with this definition, most studies in this review linked financial literacy with financial knowledge (Huston, 2010; Lusardi and Mitchelli, 2007).

To become financially literate, individuals must receive education and acquire the necessary skills and knowledge regarding financial products and services. People who receive financial education, such as financial management courses, have been shown to increase their financial literacy and ability to effectively manage their financial resources (Garman et al., 1999). As a result of their education, these individuals acquire the knowledge necessary to manage financial issues and act in their own best financial interests. Individuals with sufficient financial knowledge are more likely to plan for retirement (Alessie et al., 2011; Lusardi et al., 2010), accumulate wealth (Mahdzan and Tabiani, 2013), and manage their personal finances on a daily basis (Delafrooz and Paim, 2011). Financial education is necessary to acquire financial knowledge and literacy, making the two inextricably linked.

In the US, research has shown the need for increased financial education for young adults to improve their understanding of loans and budgeting, especially for those from underrepresented groups (Eichelberger et al., 2017). Children learn best by accumulating experiences rather than being taught formal financial concepts (Collins and Odders-White, 2015; Sherraden et al., 2011). This suggests practical simulation is the most effective method for explaining financial concepts at an early stage. Past studies have found that children whose parents provide opportunities to learn about money have a greater understanding than children whose parents do not (Marshall and Magruder, 1960).

These findings align with Sherraden et al. (2011), who found that the financial capability of young children is increased with access to financial education and savings accounts. Children who participated in the I Can Save programme scored significantly higher in financial literacy than those who did not. These higher scores could be attributed to three factors: (1) they received more financial education, which was more ‘fun’ (experiential) than classroom learning; (2) some of the parents also received financial education, and may have encouraged and augmented their children’s learning; and (3) the children may have been especially motivated to learn because of their savings accounts and visits to the bank. Early financial education for young adults ensures that they will be able to successfully confront the increasingly complex financial issues and decisions they will face as they enter adulthood. Financial education has been the primary intervention in helping generations of young adults to become financially literate, avoid high-risk financial behaviour, and make better financial decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014).

In Pakistan, as in the US, financial education programmes aimed at enhancing the financial capabilities of young adults have been implemented across education levels (Noreen et al., 2019). Financial education at all educational levels improves the financial attitudes of youth and significantly impacts financial capability. Financial education to increase the financial knowledge and capability of youth may be presented in various media formats such as newsletters, publications, television, and the Internet, as proposed by a study conducted in Thailand (Amonhaemanon and Vora-Sitta, 2020). Evidence has also shown that financial education projects using locally developed programmes have a positive impact on increasing financial knowledge in young adults (Zhu, 2020).

Financial behaviour

Financial behaviour is the behaviour of humans that is associated with money management (Xiao, 2008). In the US context, as well as the Asia-Pacific region, the ability to engage in desirable financial behaviour influences the financial capabilities of young adults (Czar et al., 2021; Friedline and West, 2016; Noreen et al., 2019; Serido et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2015, 2020; Zhu and Chou, 2018). Engaging in desirable financial behaviours suggests the existence of financial capability and adequate financial literacy. Young adults who demonstrate desirable financial behaviours may have better financial well-being compared to those who exhibit undesirable financial behaviours.

Engaging in help-seeking behaviours and performing short-term/long-term financial behaviours also improve perceived financial capability among young adults (Fan, 2021). Help-seeking behaviour is defined as actively seeking information, advice, therapy, or general assistance from other sources (Rickwood et al., 2005). According to Fan (2021), younger and older adults differ in how they seek financial advice. Older adults tend to seek advice on savings and investment, while younger adults are more likely to seek advice related to insurance, debts, and loans. Xiao (2008) divided financial behaviours into one-time, short-term actions (e.g., saving for a gift) and long-term commitments (e.g., saving for retirement). Young adults who are experiencing stressful life events such as job loss, unemployment, or home foreclosure may seek financial advice from others as it can be a helpful stress reliever for young adults in difficult situations. Evidence from a study in the United States indicated that young adults’ perceived financial capability is related to financial advice-seeking behaviour and short- and long-term financial behaviour (Fan, 2021). Parents play a critical role in influencing young adults’ financial advice-seeking behaviour and their short- and long-term financial behaviours. Furthermore, the demand for professional financial advice would also increase.

Financial attitude

Several studies have also explored financial attitude as a variable that influences financial behaviour (Serido et al., 2013; Shih and Ke, 2014). Attitude substantially influences financial decision-making, as it is significantly related to financial management behaviour (Yap et al., 2018). In the theory of planned behaviour, attitude is crucial to comprehend behaviour (Azjen, 1991), and financial attitudes precede financial behaviour (Potrich et al., 2016). Numerous studies on young adults’ financial attitudes in the United States and Asian countries have established a link between financial attitudes and financial capability in young adults who have received financial education or have an adequate level of financial literacy (Amonhaemanon and Vora-Sitta, 2020; Loke et al., 2015; Noreen et al., 2019). Increased financial knowledge among young adults is assumed to improve their financial attitudes and behaviour and, thus, their financial capabilities. Financial education targeted at young adults is crucially important because it increases their financial literacy and improves their financial attitudes and behaviour.

Financial inclusion

Unfortunately, financial education may not be enough to shape financial behaviour and capability, especially for young adults who must make decisions in uncertain economic conditions. Scholars have recommended pairing financial knowledge with financial inclusion to generate better financial decision-making (Sherraden, 2013). This combination entails offering financial education while influencing institutional arrangements by establishing savings accounts for experiential learning. According to a growing body of evidence, developing the financial capabilities of young adults requires the acquisition of financial knowledge as well as the opportunity to establish healthy financial habits through access to financial products (Friedline and West, 2016; Huang et al., 2015; West and Friedline, 2016). Young adults who received financial education and had access to formal financial institutions were more likely to be able to afford unexpected expenses and save for emergencies, and less likely to utilise alternative financial services. They were also less likely to have burdensome debts (Friedline and West, 2016). The combination of a person’s ability to act with their opportunity to act contributes to their financial functioning in ways that lead to improved financial capability and well-being (Johnson and Sherraden, 2007).

Regrettably, research highlighting financial inclusion as a factor influencing young adults’ financial capability has only been undertaken in the US to date. Financial inclusion is defined as having access to a wide range of financial products (Lenka and Barik, 2018), with the percentage of adults who have bank accounts representing a country’s overall financial inclusion in a country. According to the Findex 2017, globally, as many as 1.7 billion adults remain unbanked, or without an account at a financial institution or through a mobile money provider. Virtually all of these unbanked adults live in the developing world, specifically in Asia, and nearly half live in just seven developing economies—Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, and Pakistan (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2018). Future studies related to financial inclusion as one of the determinants of young adults’ financial capabilities arre vital in the Asian context.

Financial socialisation

The process of developing and adopting beliefs, attitudes, norms, knowledge, and behaviour that support financial viability and well-being is known as financial socialisation (Danes, 1994). A wide variety of socialisation agents (eg. family, school, peers, and the media) aid this process, although parents are typically the primary socialisation agents (Gudmunson and Danes, 2011; Shim et al., 2010). This may be because many young adults rely on their parents for ongoing financial support (FINRA, 2009), and parents influence, whether intentionally or unintentionally, the process by which their children acquire financial understanding and knowledge. Families are a great source of information on financial processes, products, and skills for young adults (Sorgente and Lanz, 2017).

Financial socialisation from parents/family has a number of advantages, including debt reduction in emerging adulthood (Norvilitis and MacLean, 2010; Shim et al., 2010), and increased savings, higher credit scores, and lower credit card debt in adulthood (Grinstein-Weiss et al., 2011). According to Grinstein-Weiss et al. (2012), parental financial education was predictive of lower loan default and home foreclosure rates in adulthood. Parental financial education was also linked to a higher net worth and higher levels of investment (Hira et al., 2013). As primary socialisation agents, parents need to possess adequate financial knowledge, practice positive financial attitudes, and have healthy financial behaviours. Young adults can imitate parents’ knowledge, attitude, and behaviour in their daily financial decision-making.

For many adolescents in foster care, however, this is not the situation as they do not have any contact with their biological parents (Salazar et al., 2021). In the absence of a biological family, young adults in foster care rely on caseworkers as their financialsocialisation agents (Peters et al., 2016). Unlike family financial socialisation, which can last a lifetime, many of the more commonly cited sources of financial-related support for foster youth are likely to disappear once they leave the foster care system (Salazar et al., 2021).

A study in Hong Kong evaluated the development of financial capability among Chinese adolescents by extending the model of financial socialisation, which had already been tested among young adults in the US context (Shim et al., 2015; Zhu, 2018). The results were similar across the two countries in that parental socialisation can influence healthy financial behaviours. However, there were differences due to the cultural values adopted in Hong Kong. In the Confucian hierarchical culture of the Chinese communities in Hong Kong, adolescents often unconditionally accept their parents’ financial values, follow expectations, and model their financial behaviours (Zhu, 2018). These values differ from Western countries, where the relationship is not hierarchical, and everyone is considered equally important (Patil, 2020).

Demographic characteristics

There is debate as to the relationship between family income and young adults’ financial independence. Some argue that young adults from wealthy families are less likely to learn about living costs because they take their lifestyle for granted and lack the essential skills, knowledge, and, most importantly, a pressing desire to achieve financial independence. As a result, young adults from higher-income families are less likely to be financially independent (Kendig et al., 2014). Others claim that wealthy young adults are more likely to attend schools that are better suited to prepare them for adulthood (Holme, 2002), have a higher educational achievement (Björklund and Salvanes, 2011), attend university, and have more years of education (Thompson, 2014). As a result, these young adults have a better chance of earning a higher income and achieving financial independence at an earlier age (de Bassa Scheresberg et al., 2014). Kendig et al. (2014) asserted that young adults from low-income families develop financial independence early by contributing to family bills during adolescence and accepting full financial responsibility as young adults. Regardless of the relationship between income and financial independence, many young adults see a lack of income as a barrier to financial capability.

A university degree is widely regarded as a sound human capital investment. Compared to young adults without a degree, university graduates typically perform better in a variety of financial areas, including earnings (Autor et al., 2008), assets (Letkiewicz and Heckman, 2018), and employment (Cairó and Cajner, 2018). According to a previous empirical study in the US, university graduates have a significantly greater likelihood of financial independence than other young adults who do not attend university (Cui et al., 2019). Additionally, in the US context, university-educated young adults demonstrate greater objective and subjective financial knowledge, desirable financial behaviours, and a higher perceived financial capability (Xiao et al., 2020).

The Pew Research Center indicated that approximately 15% of young adults born between 1980 and 2000 (Millennials) lived with their parents (Fry, 2017). Additionally, previous empirical evidence has indicated that today’s young adults are less motivated to purchase a home than Gen Xers and Baby Boomers. Their homeownership rate is 8% lower than that of Baby Boomers and 8.4% lower than that of Gen Xers in the same age group (Choi et al., 2019). When young adults move out of their parents’ homes, they encounter a variety of new financial experiences. They begin to function independently and cease to rely on their parents for financial tasks, including paying bills, making ends meet, and making financial decisions. This increased financial responsibility likely p;rompts them to develop greater financial capabilities. A study in New Zealand found that young adults who left their parents’ homes (home leavers) experienced a significant increase in the financial capability index, suggesting that leaving home is associated with greater financial capability in young adults (Czar et al., 2021).

Several studies have explored the effects of age on the financial capabilities of young adults. Youth who have been in foster care for over 18 years have more advanced financial capabilities and related support than younger youth (Salazar et al., 2021). Older youth demonstrate a higher level of financial capability than their younger counterparts (Xiao et al., 2015). A study in Thailand revealed that young, single adults lack financial capabilities as compared to older couples (Amonhaemanon and Vora-Sitta, 2020). Financial behaviours also differ with age. As previously described, when seeking financial advice, older adults tend to seek advice on savings and investments, while the younger ones are more likely to seek advice related to insurance, debts, and loans (Fan, 2021). However, age is not always associated with increased financial capacity. A study of immigrants in the United States found that older immigrants had significantly lower financial management skills, knowledge of social programmes, and asset ownership than younger immigrants (Nam et al., 2015). An individual’s financial capability may increase throughout their lives due to both formal and informal financial education and exposure to real-world financial situations. However, for those lacking financial education and access to formal financial institutions, the situation may be different; they may not experience increased financial capability.

Developing the financial capabilities of young adults involves the acquisition of financial knowledge and practicing sound financial behaviours via access to financial products and services (Loke et al., 2015; Sherraden, 2013). Loke et al. (2015) discovered that financial capability increased when young people received financial education and had access to a savings account. Additionally, young adults in the study improved their financial knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and behaviours. The combination of financial knowledge and access to a bank account also facilitates asset accumulation, further increasing financial capability (Huang et al., 2015). Savings programmes that specifically targeted young adults benefited even economically disadvantaged youth, as they were able to save a significant amount of money with the assistance of institutional support.

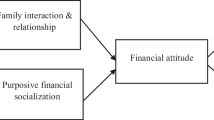

Based on the discussed findings within the literature, we suggest a conceptual framework of factors influencing young adults’ financial capabilities, as presented in Fig. 2. The rationale behind the conceptual model is to logically integrate all potential influential factors to deliver a framework that provides the most suitable explanation for the occurrence of an event (Brown et al., 1995). To synthesise the reviewed literature on young adults’ financial capability included in this systematic review, we have constructed a framework that describes associations between the constructs and antecedents of financial capability. Based on the conceptual framework, young adults’ financial capability in the US and the Asia-Pacific region is influenced by several determinants, such as (1) the combination of financial knowledge and access to financial services (financial inclusion), (2) the combination of financial knowledge and positive financial behaviours, (3) financial education, (4) demographic characteristics, (5) financial socialisation from either parents or co-workers, and (6) the process of changing financial attitude and behaviours as a result of financial education.

Recommendations

This study can offer several recommendations for future scholars. To begin, additional research is needed to examine the factors affecting young adults’ financial capabilities in the Asia-Pacific region, where over 60% of the world’s youth live, which is equivalent to more than 1.1 billion young people. Young adults living in the Asia-Pacific region must be able to make sound financial decisions because the economic impact of financially incapable young adults can be devastating. Improved financial capability among young adults impacts everything from day-to-day choices to long-term financial decisions, with consequences for both individuals and society. Young adults with limited financial capabilities are more likely to engage in inefficient spending, incur high borrowing costs, and overlook financial planning. In Malaysia, 60% of individual bankruptcies were from the younger generation as the result of their habit of spending more than their income (Rahim et al., 2022).

Future research should focus on young adults’ financial capabilities in the Asia-Pacific region, particularly in countries with a large population of young adults, emphasising the factors that influence financial capabilities. These studies are essential for several reasons. First, following the transformative United Nations’ adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), countries in the Asia-Pacific region are uniquely positioned to maximise the potential of their youth population and promote inclusive, sustainable development. Success is contingent upon increasing youth engagement in all aspects of development by recognising that young people can play a much more significant role in decisions affecting the challenges and opportunities they face and the environments that they live in. Second, if well-placed youth empowerment policies are implemented in South and Southwest Asia, youth bulge can spur growth. South Asia falls behind several other regions in terms of equipping the next generation with the skills required for 21st-century jobs (Cooper, 2019). South Asia is at a crossroads, with only a few years left to reap substantial demographic dividends from its talented and capable youth. If done correctly, millions of people can be raised out of poverty. Failure to do so will result in economic stagnation, increased youth despair, and further loss of talent to other regions.

Most studies on young adults’ financial capabilities have been conducted in the United States, where numerous financial capability programmes targeted at youth are already. Thus, future scholars should examine the factors that influence young adults’ financial capabilities in Asia, where formal financial education efforts to strengthen the financial capabilities of young adults are still lacking. With nearly half of its 1.8 billion population under the age of 24, South Asia, led by India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, will have the world’s largest youth labour force by 2040 (Cooper, 2019). This presents an opportunity for the region to foster vibrant, productive economies. If significant investments in financial education are made, the region will be able to sustain strong economic growth and expand opportunities for financial capability over the next few decades.

As with all studies, this systematic review is not without limitations. The scope of the review focused only on papers related to the financial capability of young adults from the US and Asia Pacific region, for reasons that were explained at the onset of this review. Understanding the determinants of young adults’ financial capability in other regions could provide greater insights on the factors that impact financial capability for youth globally. Future studies should perform a more thorough review to identify other antecedents of young adults’ financial capability. Another limitation in this review is that outcomes of financial capability are not covered, which should also be addressed in a future review.

Conclusion

The main purpose of this study was to systematically review the factors that contribute to the financial capabilities of young adults. This study offers several significant contributions to both the body of knowledge and practice. Interested parties, especially policymakers, the public, researchers, and youth organisations, can use the findings of this review to place more significant attention on factors that improve the financial capability of young adults. The results offer basic information on how to focus on enhancing young adults’ financial capabilities. Furthermore, the results inform the direction of future studies with regard to specific location and content of studies related to the factors that influence young adults’ financial capabilities. Financial education is mainly needed by young adults in the Asia-Pacific region to further increase their financial capabilities. Education that emphasises practical simulation is the most effective method for the early explanation of financial concepts, especially for school children. Early financial education for young adults ensures they have sufficient financial knowledge to confront the increasingly complex financial issues and decisions they will face as they enter adulthood. Increased financial knowledge among young adults improves their financial attitudes and behaviour and, thus, their financial capability. It is also crucial to pair financial knowledge with financial inclusion to generate better financial decision-making. Young adults who both received financial education and had access to formal financial institutions were more likely to perform better on several financial capability indicators. Moreover, the role of parents as primary financial socialisation agents places greater attention on their financial knowledge and education, especially in Asia where traditional hierarchical cultures place parents as the primary role model from whom young adults accept financial values. The demographic characteristics of young adults, such as income, education level, residential status, age, and participation in savings programmes, also play an important role in shaping their financial capabilities.

Data availability

This is a review paper wherein the authors have analysed various articles by different authors, all of whom have been cited as required. The cited information belongs to the authors mentioned in the reference section. The generated data are included in the paper.

References

Alessie R, Van Rooij M, Lusardi A (2011) Financial literacy and retirement preparation in the Netherlands. J Pension- Econ Financ 10:527–545. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747211000461

Alsolai H, Roper M (2019) A systematic literature review of machine learning techniques for software maintainability prediction. Inf Softw Technol 119:106214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2019.106214

Amonhaemanon D, Vora-Sitta P (2020) From financial literacy to financial capability: a preliminary study of difference generations in informal labor market. J Asian Financ Econ Bus 7:355–363. https://doi.org/10.13106/JAFEB.2020.VOL7.NO12.355

Arnett JJ (2000) Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 55:469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Autor DH, Katz LF, Kearney MS (2008) Trends in U.S. Wage inequality: revising the revisionists. Rev Econ Stat 90:300–323. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.90.2.300

Azjen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Björklund, A, Salvanes, KG (2011) Education and Family Background, In: Handbook of the Economics of Education. Elsevier, pp. 201–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53429-3.00003-X

Bonnie, RJ, Stroud, C (2015) Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults, Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults. National Academies Press (US), Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academy

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown I, Renwick R, Raphael D (1995) Frailty: constructing a common meaning, definition, and conceptual framework. Int J Rehabil Res 18:93–102

Brüggen EC, Hogreve J, Holmlund M, Kabadayi S, Löfgren M (2017) Financial well-being: a conceptualization and research agenda. J Bus Res 79:228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.013

Cairó I, Cajner T (2018) Human capital and unemployment dynamics: why more educated workers enjoy greater employment stability. Econ J 128:652–682. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12441

Charrois TL (2015) Systematic reviews: what do you need to know to get started? Can J Hosp Pharm 68:144–148. https://doi.org/10.4212/cjhp.v68i2.1440

Cheak-Zamora N, Teti M, Peters C, Maurer-Batjer A (2017) Financial capabilities among youth with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Fam Stud 26:1310–1317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0669-9

Choi, J, Zhu, J, Strochak, S, Goodman, L, Ganesh, B (2019) Millennial Homeownership. Urban Institute

Collins, JM, Odders-White, E (2021) Allowances: Incidence in the US and Relationship to Financial Capability in Young Adulthood. J Fam Econ Issues. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09748-y

Collins JM, Odders-White E (2015) A framework for developing and testing financial capability education programs targeted to elementary schools. J Econ Educ 46:105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2014.976325

Cooper, K (2019) More than half of South Asian youth are not on track to have the education and skills necessary for employment in 2030 [WWW Document]. unicef.org. URL https://www.unicef.org/rosa/press-releases/more-half-south-asian-youth-are-not-track-have-education-and-skills-necessary (Accessed 21 Nov 2021)

Cui X, Xiao JJ, Yi J, Porto N, Cai Y (2019) Impact of family income in early life on the financial independence of young adults: evidence from a matched panel data. Int J Consum Stud 43:514–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12536

Czar, K, Gilbert, A, Scott, A (2021) Life lessons: leaving home and financial capability of young adults. J Consum Aff joca.12357. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12357

Danes SM (1994) Parental perceptions of children’s financial socialization. Financ Couns Plan 5:127–149

de Bassa Scheresberg, C, Lusardi, A, Yakoboski, PJ (2014) College-educated millennials: an overview of their personal finances. Global Financial Literacy Excellent Center

Delafrooz N, Paim LH (2011) Determinants of financial wellness among Malaysia workers. Afr J Bus Manag 5:10092

Demakis, GJ, Szczepkowski, KV, Johnson, AN (2018) Predictors of financial capacity in young adults. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acy054

Demirgüç-Kunt, A, Klapper, L, Singer, D, Ansar, S, Hess, J (2018) The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution. World Bank Group, US

Eichelberger B, Mattioli H, Foxhoven R (2017) Uncovering barriers to financial capability: underrepresented students’ access to financial resources. J Stud Financ Aid 47:70–87

Elliott W, Lewis M (2015) Student debt effects on financial well-being: research and policy implications. J Econ Surv 29:614–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12124

Ergün K (2018) Financial literacy among university students: a study in eight European countries. Int J Consum Stud 42:2–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12408

Fan L (2021) A conceptual framework of financial advice-seeking and short- and long-term financial behaviors: an age comparison. J Fam Econ Issues 42:90–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09727-3

FINRA (2009) Financial Capability in the United States: National Survey—Executive Summary (Executive Summary). FINRA Investor Education Foundation, United State of America

Flemming K, Booth A, Garside R, Tunçalp Ö, Noyes J (2019) Qualitative evidence synthesis for complex interventions and guideline development: clarification of the purpose, designs and relevant methods. BMJ Glob Health 4:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000882

Friedline T, West S (2016) Financial education is not enough: millennials may need financial capability to demonstrate healthier financial behaviors. J Fam Econ Issues 37:649–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-015-9475-y

Fry, R (2017) More young adults are living at home, and for longer stretches. Pew Res Cent URL. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/05/05/its-becoming-more-common-for-young-adults-to-live-at-home-and-for-longer-stretches/ (Accessed 11 Nov 2019)

Garman ET, Kim J, Kratzer CY, Brunson BH, Joo S-H (1999) Workplace financial education improves personal financial wellness. J Financ Couns Plan 10:81

Gonçalves, VN, Ponchio, MC, Basílio, RG (2021) Women’s financial well-being: a systematic literature review and directions for future research. Int J Consum Stud. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12673

Goyal K, Kumar S, Xiao JJ (2021) Antecedents and consequences of personal financial management behavior: a systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int J Bank Mark 39:1166–1207. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-12-2020-0612

Grinstein-Weiss M, Spader J, Yeo YH, Taylor A, Books Freeze E (2011) Parental transfer of financial knowledge and later credit outcomes among low- and moderate-income homeowners. Child Youth Serv Rev 33:78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.08.015

Grinstein-Weiss M, Spader JS, Yeo YH, Key CC, Freeze EB (2012) Loan performance among low-income households: does prior parental teaching of money management matter? Soc Work Res 36:257–270. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svs016

Gudmunson CG, Danes SM (2011) Family financial socialization: theory and critical review. J Fam Econ Issues 32:644–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9275-y

Gusenbauer M, Haddaway NR (2020) Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta‐analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res Synth Methods 11:181–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1378

Gutter M, Copur Z (2011) Financial behaviors and financial well-being of college students: evidence from a national survey. J Fam Econ Issues 32:699–714

Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S (2015) The role of google scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLOS ONE 10:e0138237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

Haddaway NR, Macura B, Whaley P, Pullin AS (2018) ROSES reporting standards for systematic evidence syntheses: pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ Evid 7:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-018-0121-7

Hira TK, Sabri MF, Loibl C (2013) Financial socialization’s impact on investment orientation and household net worth: Financial socialization’s role in investment behaviour. Int J Consum Stud 37:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12003

HM Treasury (2007) Financial capability: the goverments’ long term approach. the controller of the majesty’s stationary Office, United Kingdom

Holme JJ (2002) Buying homes, buying schools: school choice and the social construction of school quality. Harv Educ Rev 72:177–206. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.72.2.u6272x676823788r

Huang J, Nam Y, Sherraden M, Clancy M (2015) Financial capability and asset accumulation for children’s education: evidence from an experiment of child development accounts. J Consum Aff 49:127–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12054

Huston SJ (2010) Measuring financial literacy. J Consum Aff 44:296–316

Johnson E, Sherraden MS (2007) From financial literacy to financial capability among youth. J Soc Soc Welf 34:29

Kendig SM, Mattingly MJ, Bianchi SM (2014) Childhood poverty and the transition to adulthood: childhood poverty and transition to adulthood. Fam Relat 63:271–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12061

Kumar S, Tomar S, Verma D (2019) Women’s financial planning for retirement: systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int J Bank Mark 37:120–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-08-2017-0165

LeBaron AB, Rosa-Holyoak CM, Bryce LA, Hill EJ, Marks LD (2018) Teaching children about money: prospective parenting ideas from undergraduate students. J Financ Couns Plan 29:259–271. https://doi.org/10.1891/1052-3073.29.2.259

Lenka SK, Barik R (2018) A discourse analysis of financial inclusion: post-liberalization mapping in rural and urban India. J Financ Econ Policy 10:406–425. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFEP-11-2015-0065

Letkiewicz JC, Heckman SJ (2018) Homeownership among Young Americans: a look at student loan debt and behavioral factors: homeownership among young Americans. J Consum Aff 52:88–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12143

Lin JT, Bumcrot C, Ulicny T, Mottola G, Walsh G, Ganem R, Keiffer C, Lusardi A (2019) The State of U.S. Financial Capability: The 2018 National Financial Capability Study (p. 45). FINRA Investor Education Foundation

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K (2015) Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc 13:179–187. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062

Loke V, Choi L, Libby M (2015) Increasing youth financial capability: an evaluation of the MyPath savings initiative. J Consum Aff 49:97–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12066

Lusardi A, Mitchell OS (2014) The economic importance of financial literacy: theory and evidence. J Econ Lit 52:5–44

Lusardi A, Mitchell OS, Curto V (2010) Financial literacy among the young. J Consum Aff 44:358–380

Lusardi A, Mitchelli O (2007) Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: evidence and implications for financial education. Bus Econ 42:35–44

Mahdzan NS, Tabiani S(2013) The impact of financial literacy on individual saving: an exploratory study in the malaysian context. Transform Bus Econ 12:16

Marshall HR, Magruder L (1960) Relations between parent money education practices and children’s knowledge and use of money. Child Dev 31:253–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1960.tb04964.x

Morris, C (2019) In Asia, Young People are Key to Achieving National Development Goals [WWW Document]. URL https://blogs.adb.org/blog/asia-young-people-are-key-achieving-national-development-goals (Accessed 9 Jun 2022)

Mottola, GR (2014) The Financial Capability of Young Adults—A Generational View, FINRA Foundation Financial Capability Insights. Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, Washington DC

Muir, K, Hammilton, M, Noone, J, Salignac, F, Marjolin, A, Saunders, P (2017) Exploring Financial Wellbeing in the Australian Context. Centre for Social Impact & Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales Sydney

Nam Y, Lee EJ, Huang J, Kim J (2015) Financial capability, asset ownership, and later-age immigration: evidence From a sample of low-income older asian immigrants. J Gerontol Soc Work 58:114–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2014.923085

Nam, Y, Loibl, C (2020) Financial Capability and Financial Planning at the Verge of Retirement Age. J Fam Econ Issues. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09699-4

Nanda, AP, Banerjee, R (2021) Consumer’s subjective financial well‐being: A systematic review and research agenda. Int J Consum Stud 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12668

Noreen, T, Abbas, M, Shabbir, MS, Al-Ghazali, BM (2019) Ascendancy of Financial Education to Escalate Financial Capability of Young Adults: Case of Punjab, Pakistan. Int Trans J Eng Management 10A15F: 111. https://doi.org/10.14456/ITJEMAST.2019.200

Norvilitis JM, MacLean MG (2010) The role of parents in college students’ financial behaviors and attitudes. J Econ Psychol 31:55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2009.10.003

O’Connor, GE, Newmeyer, CE, Wong, N, Bayuk, JB (2019) Conceptualizing the multiple dimensions of consumer financial vulnerability. J Bus Res. 100(C), 421–430

OECD (2021) Financial consumer protection and financial literacy in Asia in response to COVID-19. https://web-archive.oecd.org/2021-10-12/593924-Financial-consumer-protection-and-financial-literacy-in-asia-in-response-to-covid-19.pdf

OECD INFE (2011) Qore Questionnaire in Measuring Financial Literacy: Questionnaire and Guidance Notes for Conducting an Internationally Comparable Survey of Financial Literacy. Paris: OECD, Paris

Patil, T (2020) Understanding the Difference Between Eastern & Western Culture. Medium. URL https://medium.com/@tanmaynitinpatil/understanding-the-difference-between-eastern-western-culture-d20f94dbf956 (Accessed 9 Dec 2022)

Peters CM, Sherraden M, Kuchinski AM (2016) Growing financial assets for foster youths: expanded child welfare responsibilities, policy conflict, and caseworker role tension. Soc Work 61:340–348. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/sww042

Potrich ACG, Vieira KM, Mendes-Da-Silva W (2016) Development of a financial literacy model for university students. Manag Res Rev 39:356–376. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-06-2014-0143

Rahim RA, Munir RIS, Zainal NZ, Kassim ES (2022) An investigation of factors contributing to bankruptcy of young generation: a conceptual paper. Glob Bus Manag Res Int J 14:10

Ranta M, Salmela-Aro K (2018) Subjective financial situation and financial capability of young adults in Finland. Int J Behav Dev 42:525–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025417745382

Rickwood D, Deane FP, Wilson CJ, Ciarrochi J (2005) Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Aust E-J Adv Ment Health 4:218–251. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.4.3.218

Robinson P, Lowe J (2015) Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Aust N. Z J Public Health 39:103–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12393

Salazar, AM, Lopez, JM, Spiers, SS, Gutschmidt, S, Monahan, KC (2021) Building Financial Capability in Youth Transitioning from Foster Care to Adulthood. Child Fam Soc Work cfs.12827. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12827

Sechopoulos, S (2022) Most in the U.S. say young adults today face more challenges than their parents’ generation in some key areas. Pew Res Cent URL https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/02/28/most-in-the-u-s-say-young-adults-today-face-more-challenges-than-their-parents-generation-in-some-key-areas/ (Accessed 9 7Jul 2022)

Serido J, Shim S, Tang C (2013) A developmental model of financial capability: a framework for promoting a successful transition to adulthood. Int J Behav Dev 37:287–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025413479476

Shaffril HAM, Ahmad N, Samsuddin SF, Samah AA, Hamdan ME (2020) Systematic literature review on adaptation towards climate change impacts among indigenous people in the Asia Pacific regions. J Clean Prod 258:120595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120595

Shaffril, HAM, Samah, AA, Kamarudin, S (2021) Speaking of the devil: a systematic literature review on community preparedness for earthquakes. Nat Hazards https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-04797-4

Sherraden, M (2013) Building Blocks of Financial Capability, in: Birkenmaier, J, Curley, J, Sherraden, M (Eds.), Financial Capability and Asset Development: Research, Education, Policy, and Practice. Oxford Scholarship Online, pp. 3–43

Sherraden MS, Grinstein-Weiss M (2015) Creating financial capability in the next generation: an introduction to the special issue*. J Consum Aff 49:1–12

Sherraden MS, Johnson L, Guo B, Elliott W (2011) Financial capability in children: effects of participation in a school-based financial education and savings program. J Fam Econ Issues 32:385–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9220-5

Shih T-Y, Ke S-C (2014) Determinates of financial behavior: insights into consumer money attitudes and financial literacy. Serv Bus 8:217–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-013-0194-x

Shim S, Barber BL, Card NA, Xiao JJ, Serido J (2010) Financial socialization of first-year college students: the roles of parents, work, and education. J Youth Adolesc 39:1457–1470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9432-x

Shim S, Serido J, Tang C, Card N (2015) Socialization processes and pathways to healthy financial development for emerging young adults. J Appl Dev Psychol 38:29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2015.01.002

Shim S, Xiao JJ, Barber BL, Lyons AC (2009) Pathways to life success: a conceptual model of financial well-being for young adults. J Appl Dev Psychol 30:708–723

Sorgente A, Lanz M (2017) Emerging adults’ financial well-being: a scoping review. Adolesc Res Rev 2:255–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-016-0052-x

STATISTA (2021) Population of the U.S. by sex and age 2021 [WWW Document]. Statista. URL https://www.statista.com/statistics/241488/population-of-the-us-by-sex-and-age/ (Accessed 9 Jul 2022)

Taylor M (2011) Measuring financial capability and its determinants using survey data. Soc Indic Res 102:297–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9681-9

Thompson O (2014) Economic background and educational attainment: the role of gene-environment interactions. J Hum Resour 49:263–294. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.49.2.263

West S, Friedline T (2016) Coming of age on a shoestring budget: financial capability and financial behaviors of lower-income millennials. Soc Work 61:305–312. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/sww057

Whittemore R, Knafl K (2005) The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 52:546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Williams AJ, Oumlil B (2015) College student financial capability: a framework for public policy, research and managerial action for financial exclusion prevention. Int J Bank Mark 33:637–653. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-06-2014-0081

Winstanley M, Durkin K, Webb RT, Conti-Ramsden G (2018) Financial capability and functional financial literacy in young adults with developmental language disorder. Autism Dev Lang Impair 3:239694151879450. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396941518794500

Xiao, JJ (2020) Financial literacy in Asia: a scoping review. SSRN Electron J https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3743345

Xiao, JJ (2016) Handbook of consumer finance research. Springer Science+Business Media, New York, NY

Xiao, JJ (2008) Applying behavior theories to financial behavior, In: Handbook of Consumer Finance Research. Springer, pp. 69–81

Xiao JJ, Chen C, Sun L (2015) Age differences in consumer financial capability. Int J Consum Stud 39:387–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12205

Xiao, JJ, Huang, J, Goyal, K, Kumar, S (2022) Financial capability: a systematic conceptual review, extension and synthesis. Int J Bank Mark https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-05-2022-0185

Xiao JJ, Porto N, Mason IM (2020) Financial capability of student loan holders who are college students, graduates, or dropouts. J Consum Aff 54:1383–1401. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12336

Xiao Y, Watson M (2019) Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J Plan Educ Res 39:93–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X17723971

Yap, RJC, Komalasari, F, Hadiansah, I (2018) The effect of financial literacy and attitude on financial management behavior and satisfaction. Bisnis Birokrasi J 23. https://doi.org/10.20476/jbb.v23i3.9175

Zhu AYF (2020) Impact of financial education on adolescent financial capability: evidence from a pilot randomized experiment. Child Indic Res 13:1371–1386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09704-9

Zhu AYF (2018) Parental socialization and financial capability among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. J Fam Econ Issues 39:566–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9584-5

Zhu AYF, Chou KL (2018) Development of financial capacity in adolescents. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 35:309–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-017-0521-5

Zhu J, Liu W (2020) A tale of two databases: the use of Web of science and scopus in academic papers. Scientometrics 123:321–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03387-8

Acknowledgements

This publication is partially funded by the Faculty of Business and Economics, Universiti Malaya Special Publication Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SM worked toward conceptualisation, methodology, writing, and formal analysis. NSM and MEAS were responsible for validation, formal analysis, review, and editing. All of the authors carefully read the paper for final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations