Abstract

The paper applies Habitus-Field theory, Multiple Correspondence Analysis, and close reading to study an extinct, ancient civilization through the lense of a likewise extinct language: Tocharian. To do so, we analyze a large corpus of 5276 text fragments written from the 5th to the 10th century C.E. stemming from 25 different regions in the Tarim basin and Taklamakan desert. We include not only text contents but also archaeological features such as find spots and the materiality of the text fragments. Our analysis reveals a distinction between political, spiritual, and economic elites by referencing moral principles stemming from Buddhism. Furthermore, distinctions in terms of gift-giving, being able to control the Caravan trade, and shaping the view on the moral order of society by the act of writing itself were found.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sociology, linguistics with focus on ancient languages, and archaeology seek to answer questions on the developments of societies, cultural phenomena, and the chance of language use. Yet they are rarely in dialogue even though they might profit from each other. For example, sociology might benefit from the analysis of extinct societies and, by doing so, expanding the scope of theories and methods beyond the modern era (Bryant, 1994; Clemens, 2006; Goldthorpe, 1991; Steinmetz, 2018; Wallerstein, 2011). Simultaneously, archaeology and linguistics might profit from sociological theories and methods insofar, as they provide specialized concepts to investigate relationships between actors (Fuhse, 2009; Pachucki and Breiger, 2010), differentiated social subsystems or fields (Beckert, 2010; Bourdieu, 1984; Luhmann, 2015), development of groups, conflicts, and power relations therein (Collins and Sanderson, 2015; Legewie and Schaeffer, 2016; Schmitz et al. 2017), and decision processes (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979; Kroneberg and Kalter, 2012; Scharpf, 1991). The article at hand aims to bridge this gap by applying Habitus- Field Theory (HFT hereafter) (Bourdieu, 1984, 1990) and the associated method of multiple correspondence analysis on the Tocharian Corpus and the society which spoke this now extinct language.Footnote 1

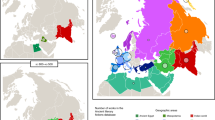

Tocharian was spoken in the borderlands between China and Tibet (see Fig. 1 for an overview of the findspots and geographic location) and consists of two languages: Tocharian A and B (TA and TB from now on). Together, they constitute a separate branch of the Indo-European language family and were actively spoken in the first millennium C.E. in the oasis city-states of the eastern Silk Road in the Northern edge of the Tarim Basin in North-West China (=present-day Xinjiang). Both languages died out in medieval times without any record or cultural continuation into modernity. To date, 6721 words have been identified in TA, of which most can give at least an approximate translation, whereas for TB, 12.607 words were identified and most translated. At present, the corpus is still in the process of edition and philological translation. We do only know about TA and TB thanks to the discovery of original documents written between the early 5th and late 10th centuries CE (Malzahn, 2007). These documents constitute either the remnants of libraries of Buddhist monasteries or of bookkeeping offices, both clerical and secular. The uses of literacy to be deduced from the corpus clearly show that initiators, authors, and target audience of the documents came from the upper stratum of the society, to be more precise, from the political and economic elites.

With this caveat in mind that we have to do with the biased perspective of the elites of the Tocharian-speaking society, the size, and contents of the text corpus, nevertheless, allows us to deduce a broad picture of the religious views, cultural practices, and socio-economic spaces of these respective city states also viewed in comparison with other historical sources and data (secular historical writing of adjacent states such as China, paintings, architecture and other archaeological evidence). The philological methods used in editing and translating the corpus, however, are specially demanding since we only possess fragments of single pages of former books due to the circumstances of their preservation and archaeological recovery (Pinault, 2008). Beside philological and linguistic methods digital tools are used in editing the corpus at the CEToM project since 2011 (Malzahn et al. 2011–2023). To date (January 2023) the corpus contains 10,289 fragments, 214,795-word tokens with 60,534 different word forms and 19,328 different lexical forms.

By analyzing the Tocharian corpus through the theoretical and empirical lens of HFT, we seek to test whether our analytical framework is applicable to 1) extinct societies and 2) extinct languages (Tocharian) which are still in the process of being edited and translated. Methodologically, we use close reading (Smith, 2016) and inductive content analysis (Schneijderberg et al. 2022, pp. 101–119) of the Tocharian texts, and Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) (Greenacre and Blasius, 2006; Le Roux and Rouanet, 2010) to extract Topics from the text fragments. Furthermore, we include information on the 25 findspots of the Tocharian text fragments, as well as the material on which these texts were written. By doing so, we provide a blueprint to analyze extinct societies by combining the lenses of sociology, linguistics, archaeology, and natural language processing (NLP).

Theoretical background

HFT is a relational social theory, which, at its heart, explains social phenomena by focusing on the (conflictual) interplay between historically grown power-relations among actors (e.g. different, powerful elites and how they are recruited), ideas, social categorizations, distribution of material, social, cultural, and symbolic resources, and how all of these combined result in social order (Bourdieu, 1984, 1996c, 2017). Furthermore, within this order, individual as well as collective actors try to make sense of this social reality and actively seek to uphold or change the order either by accumulating resources and making a specific resource the main principle of societal reproduction, e.g. wealth versus political power versus knowledge (Bourdieu, 1998; Schmitz et al. 2017). Within this framework, media, including prose, songs, pictures, and even architecture, are interpreted as manifestations of the performing actors within the historically grown social order and thus the power relations (Bourdieu, 1993, 1996b). In our case, the social reality of the Tocharian-speaking society is conveyed in the text fragments, its topics covered, as well as the materiality and findspots of the leftovers. All might be indicators of the position within the society, the ability of actors to preserve their world-views, as well as material resources at their disposal which could then be used to write and distribute their views.

The totality of the positions resulting from these material, cultural, and symbolic interrelation is defined as social space. A position within this space is consequently defined by the total volume of capital of an actor has at its disposal as well as the relative abundance of other forms of capital in relation to other actors. Actors have economic capital (e.g. money, houses, stocks), social capital (being parts in groups and social networks), cultural capital (specific knowledge, certificates), and different forms of symbolic capital (e.g. academic capital or prestige, which is linked to being acknowledged by others in the same field) at their disposal. For example, economic capital can be converted into symbolic capital, if, in our case, housekeepers with the right to take taxes on donor parts of their wealth to monasteries, which are then used to praise these housekeepers and to attribute them virtues in the text fragments. By doing so, they might be depicted as morally viable actors in the texts, and gain reputation by monks and other actors dealing with the spiritual realm.

Fields are relatively autonomous arenas like the economy or academe. Here, actors compete for the worth of their forms of capital (i.e. specific forms of knowledge and approaches in the academic field), to secure their position, to accumulate different forms of capital, and to set the tacit rules of the respective field (Krause, 2018). The unquestioned, shared belief on how a field should work (what is at stake, what are legit strategies, what forms of capital are relevant) is called illusio. Doxa, which is split into orthodoxy and heterodoxy, means the tacit agreement on how the field functions, and should be structured, whereas nomos subsume the principles of vision and division in a field, for example how actors demonstrate that they belong to the field.

Elites, who yield the highest volumes of different forms of capital and who seek to impose their views on society, the economy, morals, and values onto others and to impact the social order enter the field of power (Schmitz et al. 2017). In our case, we might see worldly elites (political and economic) and spiritual elites (monks) engage in competitions regarding the interpretation of how a society should be structured and the social hierarchy itself. This encloses a struggle regarding the worth of the profane, meaning everyday activities which keep society running, and the sacred in the sense of Durkheim (1995), meaning the (religious) representations of the social and natural order, which is to be separated from the profane.

Thus, employing HFT enables us to understand society, as described by the Tocharian text fragments, as a set of different fields. The most successful actors in these fields (=elites) with the highest volumes of capital yield the power to symbolically, culturally, and thus morally structure the social order (e.g. hierarchy of monks, secular office holders, housekeepers) and, in our case, the ability to write and to impose their view on society on its members. This ability is coined symbolic power – the power to classify and categorize people, and to distribute symbolic gains (e.g. which actors in the Tocharian-speaking society are deemed virtuous, by what means, what traits are defined as virtuous, how social groups should live to be virtuous, and what are the worldly and spiritual rewards of living a virtuous life) (Bourdieu, 2016). Symbolic rule is the internalization of these classification schemes by actors (e.g. economic elites, monks, politicians, and commoners). By doing so, these individual and collective actors strengthen the given order by acknowledging their vices and virtues. Finally, Symbolic violence is the devaluation of actors to uphold and strengthen a social order. This is given, if, for example, vices are attributed to social groups, leading to negative self-evaluations and attempts of members of these groups to actively leave it.

Finally, HFT assumes a link between the physical space and the social space (Bourdieu, 1996a, 2018). This is reflected, f.e. in the distribution of houses and dwellings, in the access to natural, social, and cultural resources (e.g. access to fertile land, parks, or libraries). Also, living in a certain place entails symbolic gains, e.g. if members of an elite populate an area, then their status will spill over to others living in the same area. Furthermore, the taste of the elites (e.g. for certain types of prose, architecture, clothing etc.) will be systematically found in areas where those lived. This enables us to reconstruct the local distribution of different elites as well as their (potential) interaction with each other via the text fragments.

In sum, HFT equips us firstly with an analytical lens on the relations between elites situated in the Tarim-basin with the ability to write and how they structure their view on society and social groups ( = collective actors). Secondly, it provides us with the theoretical concepts to link the content of the texts with the symbolically and morally loaded power structure of the society and possible conflicts stored within this structure. Thirdly, the linkage between physical space and social space allows us to include the findspots and the materiality of the media (e.g. if it is written on wood or paper) in our analysis. All three combined render HFT ideal for analyzing extinct societies, in our case the Tocharian-speaking society.

Methods

Research design

We apply a sequential mixed methods design (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2011), consisting of close reading, inductive content analysis, and Specific MCA.Footnote 2 We use metadata in addition to the text data including finding spots, linguistic information (e.g., use of Tocharian A/B, text genre), and the materiality of the sources (found on wood, textile, etc.). By doing so, we follow (Blasius and Schmitz, 2013, pp. 202–203), which state that one should reconstruct a) the relationship of the field under study to the field of power, b) the objective structure of the field (distribution of resources) and its their symbolic content, and c) the habitus present in the field.

We consider the text corpus diagnostic for our purpose even though the majority of non-secular texts consist of literary texts that are Buddhist by nature that have its origin in India which was also the view of the contemporaries. In fact, the texts were understood by contemporaries as doctrinal teachings attributed to the Buddha Lord and other spiritual elders from India. This descent from a construed past—whether genuine or imagined— made them authoritative as such by the spiritual leaders of the communities (Straube 2020). It does not matter therefore whether the doctrinal thoughts, ethic laws and narratives had an origin in India or not as long as the Tocharian community treated them as authoritative. This is supported by the pictorial program of wall paintings in monasteries which were not mere decoration but visualizations of the common doctrine (and open social spaces); for the use and own creation of the Buddhist cultural package to earn cultural capital, see in detail Malzahn & Fellner, in print). Further, an analysis of para-canonical Buddhist literature (the latter contains an open class of narratives we would call fictional in the modern sense) shows that many narratives are not based on Indic originals but are genuine Tocharian creations (Malzahn, 2018).

Close reading

We start with close reading to make sense of and identify topics within the text fragments in the original Tocharian documents. Close reading aims to uncover not only immanent meaning in the text or text fragments but also seeks to relate style, content, grammar, tone, structure, and imagery with the mode of its production and “how it worked”, e.g. how contemporaries perceived the texts (Smith, 2016, p. 60). We incorporated only text fragments large enough and with enough translated words into our close-reading analysis. These are two of the reasons why we included only 5276 out of 10288 text fragments in our analysis. Furthermore, interpreting this relation between content and its mode of production should enable us to reflect on the era a text was written (ibid., p. 70).

In the first step, one of the authors with the ability to read TA and TB performed a close reading of the text fragments. Afterwards, the other author performed a close reading of the English-translated text fragments. Despite largely different levels of expertise in regards to the text corpus and Tocharian language, both arrived at similar conclusions about potential contents (e.g. religious texts or tax documents), locations, as well as depicted social groups, and by what phrases and words the abovementioned could be captured.

Development of a coding scheme and merging with metadata

The next step before applying the MCA on the text corpus of the development of an inductive category system informed by close reading (Schneijderberg et al. 2022, pp. 101–119). This category system was then used to retrieve specific terms associated with a topic (e.g., in English translation monks/monastery or royalty, ministers, and public servants). For this purpose, regular expressions (regex) were developed and searched for in the text fragments using Python. If we found a regex pattern associated with a topic, the text fragment was assigned either 1 (=topic is present) or 0 otherwise. The regex search patterns are listed in Appendix A. This resulted in a text fragment by topic matrix. Note that the English translations were used as basis for the application of regex patterns and to perform the MCA.

In the next step, we extracted metadata from the CEToM database in the original languages and linked it to the extracted text topics using the identification number (e.g., A1-THT 634). This includes linguistic information such as the language variant used (such as archaic, dialectal, vernacular, hybrid), data on the material on which the text fragment was written, and data on the find region (name of the region). In addition, we categorized the regions containing the find spots (1 = region Kuca, 2 = Turfan Oasis, 3 = Sorcuq, 4 = southern outskirts). Despite the possibility of including missing data in the MCA (Greenacre and Blasius, 2006), we opted to exclude missing values (e.g. if the text fragment consist of disconnected words) as the performance of the specific MCA depends on the data being as complete as possible. In this way, we retained 5276 text fragments for analysis out of an original 10,288 text fragments found in 25 different regions.

Topic extraction via MCA

Specific MCA (Le Roux and Rouanet, 2010) is applied to reduce high-dimensional statistical spaces to a few dimensions that can be interpreted in terms of content. Specific MCA follows the assumption that we are able to map the social space onto a mathematical space. This mathematical space consists of a small number of dimensions, which are extracted from a data-table by scanning for variables (e.g. text genre, topics, finding a spot) which systematically co-appear across observations (text fragments).Footnote 3 The resulting space uses Euclidean geometry, meaning that it provides us with interpretable distances and positions of both variables and observations if plotted onto a system of coordinates.

Variables are divided into active and passive variables (Greenacre and Blasius, 2006). Active variables are used to span a Euclidean space and explain the variance present in the data set (e.g. the degree to which variables co-appear systematically). The greater the variance explained, the better the extracted dimensions account for the structures present in the data (textual content, locations, materials, linguistic features). The closer the variables are located to each other, the more systematically they occur together in the text fragments or are associated with the text fragments (e.g. finding spots). In other words, dimensions that can be interpreted in terms of content and combine statistical opposites - i.e., variables located at one end systematically co-occur. For example, if words such as “enlightened one,” “Buddha,” “jewel,” a site (e.g., Khitai Bazar) appear in the texts at one end of a dimension and the texts were written on paper in ink, but words such as “war,” “general,” appear on the other end and the texts were written on wood. Passive variables are not used to define the dimensional structure of the specific MCA, but are cast into this space like a kind of shadow (Blasius and Mühlichen, 2010). They illustrate properties that co-occur with the active variables, e.g., sociodemographic variables in the study of lifestyles (Bourdieu, 1984; Le Roux et al. 2008).

Nonetheless, we still must interpret our findings manually, as this technique produces results similar to the distant-reading methodology (Moretti, 2000). Fortunately, MCA allows us to visualize the dimensional structure onto a clear graph (called biplots), which then facilitates our interpretation (Greenacre, 2012). This plot permits us to simultaneously map the texts on one side, and text contents and metadata on the other.

Variables included in the analysis

We included the following four data types into our specific MCA, of which three were active and one passive. We begin with the variables set as active in our data:

Linguistic Data: language (Tocharian A/B), genre (Literaty / non-Literary), verse, prose

Media Data: material (wood, wall, textile, paper, object)

Content (categorized topics): monks/monastary; gods/buddha; jewels (as metaphor for Buddha); demons/spirits, heaven; hell; royalty; ministers, and public servants; settlement; housing types; landscapes; travel; economic terms; signums; householder; worldly goods

We furthermore included passive variables regarding regional data into the specific MCA. These include:

Regional Data: Findspot, number of fragments found at particular findspot, Region Code (1 = region Kuca, 2 = Turfan Oasis, 3 = Sorcuq, 4 = southern outskirts).

Selection of the dimension number

The specific MCA was performed using the FactoMineR package (Lê et al. 2008) in RStudio (R Core Team, 2016). However, since we cannot know in advance exactly how many dimensions we can reasonably interpret (see for example Chang et al. 2009 or Wieczorek et al. 2021 on this matter), we apply the elbow criterion to the screeplot (Fig. 2) (Krzanowski, 2000). Starting with the selection of dimensions to be interpreted, the elbow criterion we apply to Fig. 2 suggests a three-dimensional solution. The first dimension explains 18.45% of the variance, the second 9.15%, the third 6.06%, the fourth 5.58% and the fifth 5.05%.

Results

Starting with the first dimension (X-axis, Fig. 3), we see that the first dimension is characterized by the presence or absence of textual content. On the right side of the figure, religious themes emerge. They manifest in descriptions of “heaven”, “demons and spirits”, the “jewels metaphor” (as a reference to Buddha), “hell”, and, to a lesser extent, “monks/monasteries” and “gods/buddha”. In addition, “householder,” “worldly goods” (e.g. silk, livestock), “military” (generally, conquests, weapons etc.), “royalty” (king, prince, princess) and “ministers and public servants” are mentioned, which represent worldly elites with large possessions or influence. Exemplary text fragments are included in appendix B1.

Furthermore, we witness an association between places such as “settlement” (great cities) and “housing” (e.g. house, moat, estate) with “journeys” (in the spiritual as well as worldly sense). These text fragments were mainly found in important societal centers in the Tarim Basin, namely Khitai Bazar in the Kucha area and Qigexing (Yanqi). With this in mind, we interpret the first extracted dimension as texts relating to spiritual and secular elites.

The second dimension is characterized by fewer variables compared to the first dimension. Variables include the presence of signum (i.e., mention of caravan passes issued), and non-literary texts (genre: non-literary) dealing with economic issues. Text fragments characteristic for the second dimensions were written on wood tablets or on walls (see appendix B2 for exemplary text fragments). Compared to texts written on paper or textiles, the materiality and genre of these texts indicate more secular, profane texts. Some of the sites are located outside the intellectual and social centers (Miran, Saldiran), while others belong to the western core area (Qizil Qargha, Qizil). Due to content, materiality, and spatially different find spots, we interpret the second axis as an economic dimension, which at the same time indicates a functional differentiation (Münch, 1981, 1982, 2010) between intellectual and secular elites and actors who were economically active.

Dimension 3 (y-axis in Fig. 4) fans out of the first dimension. The largest difference is spanned between householder (upper right) and heaven (lower right). Above the x-axis we find contents like “housing”, “worldly goods”, “signum”, “military”, “economy” and “monks/monastery”. While clearly below the X-axis contents like “landscapes”, “demons spirits”, “jewels metaphors”, “settlement” and to a lesser extent “royalty” and “travel” are present, which were found in the Khitai-Bazar region. We interpret this contrast as secular pole (upper right, exemplary texts in appendix B3) versus spiritual pole (lower right, exemplary texts in appendix B4).

The location of the “landscapes” variable is not a contradiction here, as the text fragments frequently speak of certain individuals embarking on a spiritual journey to achieve enlightenment. Locating the nobility on the spiritual side suggests an alliance between spiritual elites and political elites. Secular and economic elites, represented primarily by the householder, are excluded from spiritual benefits.

Implicitly, the third dimension thus suggests an opposition between the ruling, political and spiritual elites, and secular elites, who have a supporting function and are below the nobility and the monks in the social hierarchy, and is hardly surprising if we consider that it was mainly monks who could write and thus left us the text fragments that we use to interpret the dimensions analyzed with the specific MCA.

Discussion

The three dimensions extracted from the data suggest a functional differentiation of the Tocharian-speaking stratum of the Tarim city-state society into a political-spiritual elite (dimension 1) and an economic elite supporting the former (dimension 3). This is in accordance with the known cultural background and a close reading of the original sources - written in Tocharian and translated in English for inclusion in the MCA - and reveals a surplus of the symbolic power of the political- and spiritual elites, which was used to morally subjugate the economic elites. In other words, we witness symbolic violence against the latter, whose role was reduced to being the support of the political-spiritual order.

The texts themselves are not the only evidence for the liaison of political and spiritual elites in the Tarim region. Besides manuscript evidence, we have secular historical writing of adjacent states such as China and we have archaeological evidence in the form of paintings, objects, and architecture. In viewing the original sources and the sources together, there can be no doubt that sponsoring the Buddhist religion was a way chosen consciously by the secular elites of the Tocharian kingdoms (the royal family and office-holding nobility) to earn cultural and symbolic capital (see in detail Malzahn & Fellner, in print).

To a certain extent, this is no surprise and in line with arguments proved by archaeologists (Adams, 2007; Nakassis, 2012), and historians – especially those who focus on the relations between worldly and spiritual elites in Buddhist regions (Adamek, 2005; Fleming, 2013). Nevertheless, we find a surprisingly clear and relevant role of economic elites in regards to trade on the silk road (dimension 2), which is combined with the role of being a supporter to the spiritual journeys and political endeavors of the political and spiritual elites (dimension 3).

In this sense, we can interpret the appearances of signums (mainly in the regions Miran, Šaldiraŋ, and Qizil Qargha) as one form of economic capital paired with the knowledge of how to tax caravans properly. The second form of economic capital is linked to householders, worldly goods (e.g. possessions, livestock, silk), and housing. Therefore, we interpret dimension 2 as linked to the praxis of accumulating economic capital, while dimension 3 depicts the physical manifestations of wealth. Yet, as indicated by the Tocharian text fragments, these possessions can be exchanged into symbolic capital when donated to Buddhist monks, nuns, or monasteries. Therefore, we find terms related to the latter at the top of dimension 3, albeit these actors are inclined to travel on their spiritual journey.

To a certain extent, these findings resemble the relations between royalty, nobility, officials, experts, and the church in medieval Europe (Dumolyn, 2007). Nevertheless, economic elites are more present and relevant in the Tocharian text corpus compared to their European counterparts.

This conclusion can not only be drawn from our text corpus, but is actually backed by other sources (historical writings, paintings showing donors, sometimes with accompanying inscriptions, architecture and other archaeological evidence). These show clearly that the maintenance of Buddhist institutions was sponsored by the local political-economical elites and, what is more, sponsoring Buddhist institutions was a conscious political agenda, a practice that started with the Mauryan dynasty in India in the 4./3rd century B.C.E. and patronage networks of local and long-distance elites were actually crucial in the spread of the Buddhist religion (Olson, 2020: 6–9). Recent research has in addition also emphasized the supportive role of sub-élite agents such as traders (Neelis, 2010; Kellner, 2019).

The local Tarim elites adopted this practice but infused it with genuine Tocharian narratives, which were not based on Indic originals (Malzahn, 2018). In fact, they accumulate cultural capital and symbolic capital and exert symbolic power (equation of social groups with virtues and vices) by using Buddhist doctrines (Malzahn & Fellner, in print). Further, as the Tarim Basin is situated at a branch of the Silk Road and otherwise a desert with limited areas of fertile land, the delicate microclimate in the Tarim Basin is closely connected with the organization of the political and organizational entities: due to the aridity, centrally administered maintenance of irrigation system was crucial for the subsistence economy of the communities which favored the retention of power in elite groups; cf. Liu (2021): “Buddhist institutions in Kucha developed a unique form, fitting the oasis environment which sustained pastoralism along with agriculture. Enough wealth was thereby created to provide sufficient livelihood for intellectual and religious pursuits”. Political and spiritual elites were therefore on the one hand strongly dependent on their economic counterparts and on the other hand their ability to extract wealth from caravans (indicated by the signums) or to get in touch with the local kingdoms of Nepal, India, and Chinese Sui, Tang and Song dynasties through the economic and elites networks serving as patronage networks (Neelis, 2010; Kellner, 2019). However, the spiritual and political elites established strategies to keep the upper hand, which is why we witness a devaluation of householders in the Tocharian text corpus, which is typical for the use of symbolic power. In this sense, housekeepers as owners of worldly possessions are both necessary for the provision of goods but are at the same time disdained as being fixated on the early realm.

The notion of householder is a term that came with the Buddhist package, it denotes any non-monastic person in contrast to a monastic person and is thus clearly hierarchical in the spiritual sense and, in our opinion, thus a social term. The Tocharian terms are either a direct loan word of the Indic original designation (Indic gṛhastha-, TB kattāke) or are a calque (that is, precise loan translation) of the original Indic term (TB osta-ṣmeñca “who stays in the house”).

The following passage illustrates the social role of householders (that is non-elite lay persons) in contrast to monastic persons and the ruling elite:

“Who dismisses all attachment, leaves all things behind him, severs all fetters, who has cleansed the mind of all things, he indeed can clearly understand the taste of monkhood. The deed takes the possessions away from some, thieves rob them from others, too. The lord, the lover takes this away, the army will make that into odour, the fire burns it, [and] the water carries it [away]. If one gives up possession and property by himself, by faith and world-weariness, he will not be able to gather a second time either. The householder must care for a lot of things, for [male] slaves and [female] slaves, for [his] wife, for sons and daughters, for the service to the king, for the land’s levy, and for [his] own possession he must care, therefore they desire possession. But if he who has gone from the house and who is eating alms that he obtained by begging, [if he] is gathering possessions, with great blemish he is besmirched.” (THT 33 a 3–6)Footnote 4

Monks who seek enlightenment will leave their righteous path (a form of symbolic exclusion and violence), if they meet housekeepers. In this sense, householders are depicted as antagonists of the spiritual and political elites. They are excluded from gaining symbolic capital besides donating economic capital to monks, nuns, and monasteries, and are depicted as morally inferior and thus not allowed to provide views on how a society should be (morally correctly) organized.

There is also evidence for the assumption that the spiritual elites were drawn from this class as well, which is also a hint that the symbolic rule - with a self-devaluation of economic elites - of the spiritual elites is at work (see Liu, 2021 on the monk and translator of Buddhist texts into Chinese Kumarajiva stemming from the royal family of Kucha on his mother’s side). Liu actually concludes:

“The theocratic Kucha regime did not allow the monastic realm to be independent free of the secular political domain. Members of royal families, not only from Kucha but also from other oases, princes and princesses joined monasteries for education. Marrying their princesses off to outstanding scholars was a general strategy of retaining talent among rulers in Central Asia.” (Liu, 2021, p. 32)

In this sense, distinction (Bourdieu, 1984) is at play, equating monks + royalty = spiritual = good = eligible to structure the gaze on a (just) society. They are worthy to travel the path of enlightenment, whereas housekeepers are equated with a fixation on earthly goods, moral corruption, and appear as antagonist on the path the enlightenment. This distinction is even more sharply drawn compared to the studies of gift giving to Buddhist communities (Adamek, 2005; Fleming, 2013), and structures the dominant gaze on society, its aims, and values.

This differentiation can also be traced spatially based on the findspots, which provide further evidence of the functional differentiation between 1) the political and spiritual nobility with narratives dealing with spiritual and political realms, vices, and virtues, and 2) the (profane) economic elites situated at other findspots with their knowledge of taxation and their worldly wealth. Thus, the description of elites is found in central locations (dimension 1), of economic processes at best as chance finds in the periphery, mostly preserved on less noble materials such as wood sticks or walls in the public sphere (dimension 2). The use of wood sticks and walls versus the use of ink on paper or silk symbolizes the division between the profane and sacred, the functionally inner-worldly versus the spiritual and valuable outerworldly. In this sense, the materials on which the text fragments were found reveal their social function. Again, the mechanism of distinction, inscribed into the physical representation of objects is at work. This offers a hint of the intersection between physical space (findspots, materiality of findings) and social space (Tocharian and Buddhist narratives, depictions of vices and virtues) which is linked to social hierarchies.

Finally, the third dimension divides spiritual and political as well as economic elites again into a secular and a religious, otherworldly pole. The latter includes the nobility and spiritual elites who monopolize the resources to embark on a spiritual journey to enlightenment. The housekeepers, as wealthy citizens, represent the secular elites who ensure the maintenance of the spiritual order. In this sense, the metaphysical, otherworldly landscapes and depictions are getting increasingly mixed with physical locations, and the more political (in terms of war and accumulation of deeds), and economic elites are addressed.

Content-wise, we see a different principle of order at this point than is usual in today’s societies. Here, it is primarily a coalition of economic and political elites that dominate, some of which are linked to scientific elites (Rossier et al. 2022; Rossier and Benz, 2021; Schneickert, 2018; Wieczorek, 2022). In contrast, the cultural, political, and spiritual elites exercise symbolic dominance over the secular elites. In our case, this manifests in the fact that interpretive authority rests with religious elites who have access to scripture and the ability to shape the gaze on society while being able to exclude economic elite and commoners from doing so.

The art of writing itself and the authoritative text canon was brought into the Tocharian society via the Buddhist religious centers of the Kucha kingdom where not only the Indic script has been adapted (a one-time process) but also where orthographic rules were established that were subsequently introduced into other regions of the Tocharian B and A speaking areas (Malzahn, 2007).

Furthermore, religious elites shape the norms, values, and gaze on society by writing pedagogical guidelines for being able to be a worthy part of society. They preserve the cosmic order, and support the nobility, but are at the same time supported by the political elites – and to a certain degree also the economic elites which seek to gain symbolic capital through donations. Nonetheless, it is also worth noting who is not addressed at all: the common people. Their exclusion tells us firstly, that elites in the Tarim basin were indifferent towards them, signifying commoners were not worthy of taking part in the field of power. Commoners were made invisible, and at the same time did not yield as much economic capital (e.g. by taxation of caravans) as householders translatable into symbolic capital in the spiritual sense. This is unless they are secondly public servants, ministers, and elders who at least had the ability to consecrate the decisions of kings or appear as being able to get enlightened by Buddha and his followers. In this sense, they appear as functional equivalent to middle classes who have symbolic means to strengthen (or weaken) the rule of the political and spiritual elites.

Regarding the questions raised at the beginning of the article, we conclude 1) that we not only can apply our analytical framework to extract structures from fragmentary language corpora, but also reconstruct valuable information about the condition, hierarchies, and spatial distribution (according to sites) of the society at that time. However, we can only interrelate the content of the text fragments and the wider structure of the Tocharian-speaking society by the interpretation of the content and meanings gained by close reading and the subsequent development of a coding scheme. Nonetheless, we must keep in mind that the sources do not provide a neutral picture of the Tocharian society, but depict spiritual, moral, political, and economic practices, hierarchies, and valuations from the perspective of elites. Furthermore, this works only under the assumption that the sources were not preserved by chance, but at the places with a higher probability of being preserved, which were associated with the corresponding social functions (spiritual, political, economic). Insofar, we conclude that 2) the combination offered by MCA and close reading, as well as the conceptual tools offered by HFT can guide linguists, historians, archeologists, and sociologists alike who seek to reconstruct the social order of an extinct society using its language(s).

Like any study that uses empirical data, our study has certain limitations. Firstly, the sources and remains used were not randomly distributed across the sites. Secondly, only primarily texts were preserved which are written by social elites for an audience consisting of other social elites. Thus, the CEToM corpus does not provide a neutral picture of the society living in the Tarim Basin during the 6th to 10th centuries AD. Thirdly, we could only map the gaze of societal elites and the social space from the Tocharian Corpus as static objects, as many sources are not dated yet. Another limitation is the amount of variance (29.8%) explained by the three extracted dimensions. While this may be considered moderate overall, it is satisfactory since we rely on a fragmentary corpus. Nonetheless, we can also view this fact in a positive light and argue that the unexplained variance suggests that we potentially have topic dimensions present in the textual material which could be explored in more detail in the future. Furthermore, many sources are still in the process of being published and could therefore not be included in our analysis. Finally, we could not actually reconstruct the habitus of the people who spoke Tocharian by relying on the text corpus only and we refrain from ascribing a “habitus” ex post, as many historical studies did (Grig, 2018; Harvey, 2000; Steckel, 2019).

Despite these limitations, the extinct society described in the CEToM is characterized by a close link between spiritual and political elites in opposition to a dominated economic elite. Even more, the application of HFT, MCA and NLP methods on fragmentary, linguistic corpora from the Middle Ages or antiquity can help expand the time horizon of social science analyses and test theories that are primarily tailored to contemporary societies against ancient societies. Following Steinmetz (2018, p. 12), we might add, that the possibility to shape the view of the successors in a given society (such as future generations), what is at stake (worldly goods versus spiritual goods), and who have legitimately access to worldly and spiritual goods is a structuring principle of society. In other words, this is time-transcending boundary work (Lamont, 2012), which enables elites to preserve norms, views, and wealth and shield them from different social strata over generations. The latter are simply excluded by the fact that they did not have the opportunity to write and preserve their views in terms of written traditions or remains.

Against this backdrop, we may draw two conclusions. First, this coupling indicates a degree of social differentiation which might be in parallel with the differentiation of the field of power. Secondly, we witness that the materiality of the findings and findspots is as important as the content, but is usually neglected in the analysis of contemporary social problems and societies. In this sense, sociology could benefit from considering both archaeological as well as linguistic sources. The caveat for linguistics and archaeology is in the application of NLP methods in combination with sociological methods (MCA), which enable these disciplines to extract structures from the data and to include information stored in databases to contrast and back up their interpretation of primary sources.

Finally, we advise that future sociological studies on the history of extinct civilizations should apply archaeological accounts of the sites and leftovers of ancient practices, as these may be used as a hint of how this civilization structured the social space in their physical manifestations. This must always be tied back to linguistic and textual cues to establish symbolic exclusion principles and views on how a society should be morally structured. If applicable, future studies should use changes in the languages over time and the tropes covered to carve out symbolic revolutions (=changes in the association between values and social strata and practices), and to identify which actors populated the field of power or were deemed worthy of being named–even if it is as antagonist or morally inferior. Furthermore, ancient statistical census data (where available) could be used to uncover lines of distinctions between regions, e.g. to uncover trade routes, civic centers, political centers, or religious centers, and therefore provides. a comprehensive theoretical and methodological underpinning for historical and archaeological studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UF8DHK. To acquire the raw data, please contact Melanie Malzahn.

Notes

We apply HFT as it was partly used in historical and archaeological research (Adams, 2006, 2007; Bahl, 2017; Dumolyn, 2007; Fleming, 2013; Greene et al., 2008; Luley, 2014; Nakassis, 2012; Pantou, 2014; Steckel, 2019; Steel, 2016; Wickham, 2014) and is specialized in reconstructing social phenomena and societies from different types of data. These types of data include text data, physical location, reputation, embeddedness in social networks, or having properties or money at disposal.

The Python and R workflow as well as analyzed data and output are uploaded on Harvard Dataverse and can be retrieved using the following link: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UF8DHK.

To extract the dimensions from a data matrix (here: text fragments by content and metadata), a singular value decomposition procedure is employed (Nenadic & Greenacre, 2007). In this process, a data matrix is decomposed into three matrices, mapping variables and observations onto a low-dimensional mathematical space. Second, Eigenvalues allow us to estimate the degree of random noise and structure present in the data.

Translation: Hannes Fellner at https://cetom.univie.ac.at/?m-tht33.

References

Adamek WL (2005) The impossibility of the given: representations of merit and emptiness in medieval Chinese Buddhism. Hist Relig 45(2):135–180. https://doi.org/10.1086/502698

Adams E (2006) Social strategies and spatial dynamics in neopalatial crete: an analysis of the North-Central Area. Am J Archaeol 110(1):1–36

Adams E (2007) “Time and Chance”: unraveling temporality in North-Central Neopalatial Crete. Am J Archaeol 111(3):391–421

Bahl CD (2017) Reading tarājim with Bourdieu: Prosopographical traces of historical change in the South Asian migration to the late medieval Hijaz. Der Islam 94(1):234–275

Beckert J (2010) How do fields change? The interrelations of institutions, networks, and cognition in the dynamics of markets. Organ Stud 31(5):605–627

Blasius J, Mühlichen A (2010) Identifying audience segments applying the “social space” approach. Poetics 38(1):69–89

Blasius J, Schmitz A (2013) Sozialraum- und Habituskonstruktion Die Korrespondenzanalyse in Pierre Bourdieus Forschungsprogramm. In: Lenger A, Schneickert C, Schumacher F (Eds) Pierre Bourdieus Konzeption des Habitus: Grundlagen, Zugänge, Forschungsperspektiven. Springer Fachmedien, Wiesbaden, p 201–218. 10.1007/978-3-531-18669-6_11

Bourdieu P (1984) Distinction.A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Bourdieu P (1990) The logic of practice. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Bourdieu, P. (1993). The field of cultural production: Essays on art and literature. Columbia University Press

Bourdieu P (1996a) Physical space, social space and habitus. Vilhelm Aubert Memorial lecture, Report, 10

Bourdieu P (1996b) The rules of art: Genesis and structure of the literary field. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Bourdieu P (1996c) The state nobility: Elite schools in the field of power. Polity Press, Oxford

Bourdieu, P. (1998). Practical reason: On the theory of action. Stanford University Press

Bourdieu P (2016) Die männliche Herrschaft (J. Bolder, Übers.; 3. Auflage). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main

Bourdieu P (2017) Über den Staat: Vorlesungen am Collège de France 1989–1992. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main

Bourdieu P (2018) Social space and the genesis of appropriated physical space. Int J Urban Reg Res 42(1):106–114

Bryant JM (1994) Evidence and Explanation in History and Sociology: Critical Reflections on Goldthorpe’s Critique of Historical Sociology. Br J Sociol 45(1):3–19

Chang J, Gerrish S, Wan C et al (2009) Reading tea leaves: How humans interpret topic models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 288–296

Clemens ES (2006) Sociology as a historical science. Am Sociol 37(2):30–40

Collins R, Sanderson SK (2015) Conflict sociology: A sociological classic updated. Routledge, London

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL (2011) Choosing a mixed methods design. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods. Research 2:53–106

Dumolyn J (2007) The political and symbolic economy of state feudalism: The case of late-medieval Flanders. Hist Mater 15(2):105–131

Durkheim E (1995) Elementary Forms Of The Religious Life (Reprint). Free Press, New York

Fleming BJ (2013) Making land sacred: inscriptional evidence for Buddhist Kings and Brahman priests in Medieval Bengal. Numen 60(5–6):559–585

Fuhse JA (2009) The meaning structure of social networks. Sociol Theory 27(1):51–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/40376109

Goldthorpe JH (1991) The Uses of History in Sociology: Reflections on Some Recent Tendencies. Br J Sociol 42(2):211–230. https://doi.org/10.2307/590368

Greenacre M (2012) Biplots: The joy of singular value decomposition. Wiley Interdiscip Rev: Comput Stat 4(4):399–406

Greenacre M, Blasius J (2006) Multiple correspondence analysis and related methods. Chapman and Hall/CRC, London

Greene ES, Lawall ML, Polzer ME (2008) Inconspicuous consumption: The sixth-century BCE shipwreck at Pabuç Burnu, Turkey. Am J Archaeol 112(4):685–711

Grig L (2018) Caesarius of Arles and the campaign against popular culture in late antiquity. Early Mediev Eur 26(1):61–81

Harvey DC (2000) Continuity, authority and the place of heritage in the medieval world. J Hist Geogr 26(1):47–59

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47(2):263–291

Kellner B (2019) Buddhism and the Dynamics of Transculturality: New Approaches. De Gruyter, Berlin

Krause M (2018) How fields vary. Br J Sociol 69(1):3–22

Kroneberg C, Kalter F (2012) Rational choice theory and empirical research: methodological and theoretical contributions in Europe. Annu Rev Sociol 38(1):73–92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145441

Krzanowski W (2000) Principles of multivariate analysis (Vol. 23). OUP, Oxford

Lamont M (2012) Toward a comparative sociology of valuation and evaluation. Annu Rev Sociol 38(1):201–221. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120022

Le Roux B, Rouanet H (2010) Multiple correspondence analysis. Sage, London

Le Roux B, Rouanet H, Savage M, Warde A (2008) Class and cultural division in the UK. Sociology 42(6):1049–1071

Lê S, Josse J, Husson F (2008) FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J Stat Softw 25(1):1–18

Legewie J, Schaeffer M (2016) Contested boundaries: Explaining where ethnoracial diversity provokes neighborhood conflict. Am J Sociol 122(1):125–161

Liu X (2021) Kumarajiva and Kucha in His Time. Stud People’s Hist 8(1):28–32

Luhmann N (2015) Die Gesellschaft der Gesellschaft. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt AM

Luley BP (2014) Cooking, class, and colonial transformations in Roman Mediterranean France. Am J Archaeol 118(1):33–60

Malzahn M (2007) The most archaic manuscripts of Tocharian B and the varieties of the Tocharian B language. Instrumenta Tocharica. Heidelb: Winter 255:297

Malzahn M (2018) A contrastive survey of genres of Sanskrit and Tocharian Buddhist Texts. Writ Monum Orient 1:3–24

Malzahn M & Fellner H (in print) The Pre-Islamic Tarim Region as Borderland(s). Contextualizing Imperial Borderlands (9th c. BC – 9th c. AD, and Beyond). Verlag der Österreichischen Wissenschaften, Wien

Malzahn M, Braun M, Koller B et al (2011–2023) A comprehensive edition of Tocharian manuscripts. University of Vienna. Available via https://cetom.univie.ac.at//. Accessed January, 6, 2023

Moretti F (2000) Conjectures on world literature. N. Left Rev 1:54–68

Münch R (1981) Talcott Parsons and the Theory of Action. I. The structure of the Kantian Core. Am J Sociol 86(4):709–739. https://doi.org/10.1086/227314

Münch R (1982) Talcott Parsons and the Theory of Action. II. The continuity of the development. Am J Sociol 87(4):771–826

Münch R (2010) Theory of Action (Routledge Revivals): Towards a New Synthesis Going Beyond Parsons. Routledge, London

Nakassis D (2012) Prestige and interest: Feasting and the king at Mycenaean Pylos. Hesperia 81(1):1–30

Neelis J (2010) Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks. Brill, Leiden

Nenadic O, Greenacre M (2007) Correspondence analysis in R, with two-and three-dimensional graphics: The ca package. Journal of Statistical Software: 20(3):1–13

Olson C (2020) The Different Paths of Buddhism. Rutgers University Press, Ithaca

Pachucki MA, Breiger RL (2010) Cultural holes: Beyond relationality in social networks and culture. Annu Rev Sociol 36:205–224

Pantou PA (2014) An architectural perspective on social change and ideology in Early Mycenaean Greece. Am J Archaeol 118(3):369–400

Pinault GJ (2008) Chrestomathie tokharienne: Textes et grammaire: Ouvrage couronné par le prix” Emile Benveniste” de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Peeters, Leuven

R Core Team (2016) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available via https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 30th Jan 2023

Rossier T, Benz P (2021) Forms of social capital in economics: The importance of heteronomous networks in the Swiss field of economists (1980–2000). In: Rossier T, Benz P (eds) Power and Influence of Economists. Routledge, London, p 227–247

Rossier T, Ellersgaard CH, Larsen AG, Lunding JA (2022) From integrated to fragmented elites. The core of Swiss elite networks 1910–2015. Br J Sociol 73(2):315–335

Scharpf FW (1991) Games real actors could play: The challenge of complexity. J Theor Polit 3(3):277–304

Schmitz A, Witte D, Gengnagel V (2017) Pluralizing field analysis: Toward a relational understanding of the field of power. Soc Sci Inf 56(1):49–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018416675071

Schneickert C (2018) Globalizing political and economic elites in national fields of power. Hist Soc Res 43(3):329–358

Schneijderberg C, Wieczorek O, Steinhardt I (2022) Qualitative und quantitative Inhaltsanalyse: Digital und automatisiert, 1st ed. Beltz Juventa, Weinheim

Smith, B. H. (2016). What was “close reading”? A century of method in literary studies. The Minnesota Review, 2016(87), 57–75

Steckel S (2019) Historicizing the religious field: adapting theories of the religious field for the study of medieval and Early Modern Europe. Church Hist Relig Cult 99(3–4):331–370

Steel L (2016) Exploring Aredhiou: New light on the rural communities of the Cypriot hinterland during the Late Bronze Age. Am J Archaeol 120(4):511–536

Steinmetz G (2018) Bourdieusian Field Theory and the Reorientation of Historical Sociology. In: Medvetz T, Sallaz JJ (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Pierre Bourdieu. OUP, Oxford, p 601–628. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199357192.013.28

Straube M (2020) Narratives: South Asia. Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism Online. https://doi.org/10.1163/2467-9666-enbo-all. Consulted online on 10 August 2023

Wallerstein I (2011) The Modern World-System II: Mercantilism and the Consolidation of the European World-Economy, 1600–1750. University of California Press, Berkeley

Wickham C (2014) The ‘feudal revolution’and the origins of Italian city communes. Trans R Hist Soc 24:29–55

Wieczorek O (2022) Die Universität im Feld der Macht. Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Wieczorek O, Unger S, Riebling J et al. (2021) Mapping the field of psychology: Trends in research topics 1995–2015. Scientometrics 126(12):9699–9731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04069-9

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude towards the organizers and participants of the methods conference titled “Relational Spatial Methods”, especially Séverine Marguin, Hannah Wolf, Christian Schmidt-Wellenburg, Jan Fuhse, and Andreas Schmitz, whose input was of tremendous help. Also, we thank Hannes Fellner, Bernhard Koller and Martin Braun for data curation and for providing us the raw data. The CEToM-project was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), project number Y492.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OW and MM developed and contextualized the research idea; MM translated the corpus; OW and MM conducted close reading and developed the coding scheme; OW did the programming; OW conducted the quantitative analyses and created the visualizations; OW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. OW and MM discussed, reviewed, and edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

No informed consent was needed as this study did not include human subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wieczorek, O., Malzahn, M. Exploring an extinct society through the lens of Habitus-Field theory and the Tocharian text corpus. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 56 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02503-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02503-2