Abstract

Despite advances in women’s access to managerial positions, the glass ceiling still restricts women’s participation in corporate decision-making. Theoretical studies have examined the determining factors and career alternatives for women’s professional development to understand the roots of this problem. However, analysis aimed at establishing the causal relationships and exploring the implications of this phenomenon is missing from the literature. To fill this gap, this paper provides an overview of the determinants of the career development of women executives and explores how these factors influence their alternatives for professional development. A sample of Spanish women executives is examined using multicriteria decision techniques, and associations are established between factors and alternatives for women executives’ career development. This paper contributes to the topic of gender in management literature by enhancing the theoretical foundations and empirical validation surrounding the phenomenon of the glass ceiling. It has managerial implications in providing companies with an empirical basis for understanding the orientation of women’s career development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In developed societies, important economic, social, political and technological changes have led to a new relationship between work and family (Barnett, 2004). This relationship is concerned with the responsibilities of men and women regarding tasks in the work and family spheres. The literature has examined the repercussions of the incorporation of women into the workplace, given that they are the group that is most heavily affected by the work–family relationship. In the last two decades, researchers have shown a growing interest in this area (Rodríguez, 2009; Mensi-Klarbach, 2014; Babic and Hansez, 2021). This research refers to the glass ceiling as it suggests the growing inequalities between men and women as they progress in their professional careers within the organization (Cotter et al., 2001).

The glass ceiling refers to the fact that a qualified person wishing to advance within the hierarchy of his or her organization is stopped at a lower level due to discrimination. Thus, the glass ceiling refers to the vertical discrimination that most often occurs against women in organizations (Bendl and Schmidt, 2010) and the discriminatory barriers that prevent women from reaching positions of power or responsibility and advancing to higher positions within an organization simply because they are women (Li, Wang Leung, 2001; Jackson and O’Callaghan, 2009; Zeng, 2011). According to Díez-Gutiérrez et al. (2009), the glass ceiling explains the low level of women’s leadership in organizations, given the invisible barriers that limit their access.

The study of the glass ceiling, in terms of its determining factors, has received scholars’ attention (Kaftandzieva and Nakov, 2021).

In an attempt to remove the glass ceiling, authorities are implementing legislation and public policies to stop discrimination against women in the workplace and encourage a work–life balance. However, these actions usually have little impact at the executive level, given that they are more focused on the lower echelons of the organizational pyramid. Women are still largely underrepresented in management and decision-making processes across all sectors (Babic and Hansez, 2021).

Studies of the glass ceiling tackle the issue from different perspectives (Selva et al., 2011). Much of the literature focuses on the obstacles (barriers) and opportunities (facilitators) for women in developing their careers as executives (Van’t Foort-Diepeveen et al., 2021; Zabludovsky, 2007). Studies of experience and action have examined the perceptions of women throughout their career paths, with a special focus on the analysis of entrepreneurship (Akpinar-Sposito, 2013). Compare-and-contrast studies have shown differences between men and women in terms of leadership, expectations and gender (Klenke, 2003). Studies of professional success refer to the outcomes and achievements that explain the progress of women and predict the success of women executives (Hopkins and Bilimoria, 2008). A focus on institutional solutions is found in studies that propose measures for equitable promotion and diversity management to encourage the presence of women in executive positions (Sullivan and Mainiero, 2008).

Most of these studies focus on the inequality between the careers of women and those of men (Ackah and Heaton, 2003) and the determining factors in women’s career development (Doubell and Struwig, 2014). However, there is a gap in the literature left by the scarcity of studies that examine the factors of women’s professional development and link them to the alternatives for women on their executive career path. Women’s choice of alternative for career development is, in essence, a decision problem, conditioned by a series of factors and scenarios (Nyberg et al., 2015). Moreover, almost all the existing studies are theoretical, with a lack of empirical research in this area. In this context, this study poses the following research question: what are the determining factors in the career of women executives and how do they relate to the alternatives available to women in their managerial careers?

The aim of the current paper is to offer an empirical analysis of the determining factors in the career of women executives and examine how they influence the alternatives for such women. The paper thus responds to calls by Elacqua et al. (2009) to further the understanding of the glass ceiling by examining other potentially important variables. This study is an attempt to enrich the model proposed by Elacqua et al. (2009) by including additional factors and complete the analysis with the inclusion of professional development alternatives.

This study follows the traditions of research on barriers/facilitators and professional success. The aim is to identify the factors that not only limit but also encourage the professional development of women executives and then link these factors to different career alternatives. To achieve this aim, a theoretical model of analysis, with several corresponding hypotheses, is presented. These hypotheses are then empirically tested using a multicriteria decision model. The empirical analysis uses data from a questionnaire completed by women executives.

The originality of the study is based on the association of factors (both barriers and facilitators) and alternatives of development in the career of women executives, since no work has yet addressed these relationships, as well as in the empirical analysis based on multicriteria decision techniques, as a novel methodology in the analysis of the gender issue in the management literature.

By investigating these issues, the present study addresses specific recommendations while filling gaps in the literature on the glass ceiling. Through this research, it is hoped that a better understanding of this phenomenon can be achieved by considering both its antecedents and its possible consequences for women’s career development.

Background: theoretical framework

Determining factors of women’s career development

The literature on the factors that determine the career development of women executives provides a number of classifications of these factors. There is no universally accepted classification, but there is agreement regarding the most influential factors.

One way of classifying these factors is to separate them into factors related to the social context, organizational context, and individual context (e.g. Mensi-Klarbach, 2014; Fagenson, 1990). In the social context, organizations operate within an environment with certain circumstances, where vertical and horizontal segregation emerges as an element that determines the career of women. The organizational context refers to the behaviour of organizations, which should take into consideration gender identity and equality. The individual context refers to the individual characteristics of people, which have a direct impact on the contribution of women executives to organizations. For example, Oakley (2000) differentiated between corporate (or organizational) factors, which relate to processes of recruitment, selection, retention and promotion of women, and cultural and behavioural factors, which relate to social factors based on leadership style and power stereotypes.

Other classifications differentiate between positive and negative factors (Pletzer et al., 2015; Dezsö and Ross, 2012). Such classifications place the focus on the positive or negative impact of the presence of women in top management on business performance.

Most authors differentiate between internal and external factors (Akpinar-Sposito, 2013). External factors are those of a sociodemographic nature, which define differences in leadership and gender stereotypes. Internal factors are those of a cultural nature, which have a key function in female gender roles. They are also linked to the socially desirable behaviour of women, which is associated with a sense of duty, a willingness to serve, and a lack of competitiveness or ambition to hold power.

A widely used classification is that of Elacqua et al. (2009), who separated factors into interpersonal and situational factors. Examples of interpersonal factors are mentoring, the existence of an informal network of senior managers and friendly relations with company decision-makers. These concepts are all related to career advancement. Examples of situational factors are the existence of objective criteria for company procedures such as hiring and promotion and the number of women who have been in management positions long enough to be seriously considered for promotion.

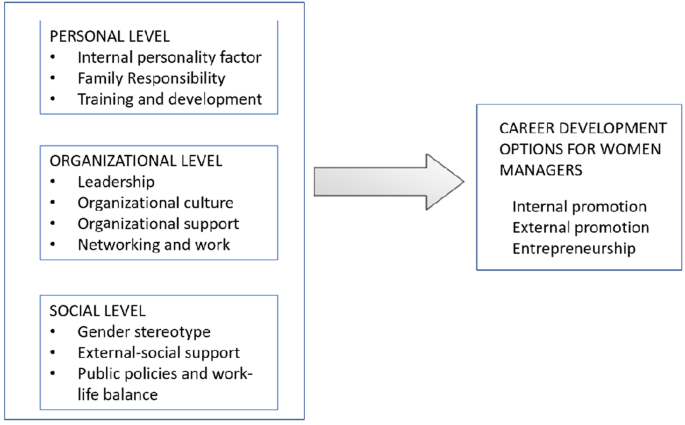

Based on these examples from the literature, a classification of factors was designed for this study to meet most of the aforementioned criteria. Several considerations were made. First, in the classifications discussed here, the difference between internal and external factors is unclear. External factors are those that are separate from the organization and personal circumstances, but internal factors are not clearly defined. Therefore, in the proposed classification, the label “internal factor” has been replaced by “personal factor” to cover factors that depend directly on the personal and individual circumstances of each woman. Second, to capture factors that refer to the social context, such as gender stereotypes and public policies, the label “social factors” is used. Finally, organizational factors are clearer in terms of content. This group of factors has been retained, as in many previous classifications. Hence, the classification used for the present study consists of personal, organizational and social factors.

Personal factors are those that are individual and inherent to each person. This category includes family responsibility, education and development, and internal factors. The literature examines family responsibility from an individual woman’s perspective in terms of marital status, number of children, age, type of family, and so on (Zabludovsky, 2007; Cuadrado and Morales, 2007). Education and development act as a differentiator linked to each and every person. Traditionally, it was said that women lacked the training needed to reach executive positions. However, this element has shifted from a barrier to a facilitator (Ridgeway, 2001). Internal factors cover elements rooted in personality, such as self-esteem, belief and confidence.

Organizational factors cover factors linked to the organization, such as leadership, organizational culture, organizational support, and social and professional networks. Leadership refers to different leadership styles and the different qualities of men or women for leadership (Rodríguez, 2009). In the organizational sphere, leadership is described as a masculine pursuit (O’Neil et al., 2008). The organizational culture, or the values shared by all members of an organization, directly depends on the organization (Peters and Waterman,1982). Organizational support refers to the internal support that a company gives its members (Bilimoria and Piderit, 2007). A lack of mentors and role models is also considered by some authors (Giscombe and Mattis, 2002; Cohen et al., 2020). The social or professional network refers to the relationships that are directly or indirectly linked to work and that give women access to resources that can affect their progress. Examples of these resources include salaries, promotions, and personal and professional recognition. These networks provide access to valuable resources and information for professional development (Terjesen, 2005; Dezsö and Ross, 2012).

Social factors are shaped by the context and contingencies of the outside world. They include gender stereotypes, as well as public policies and work–life balance policies. Gender stereotypes are the ideas that men and women have about the other gender depending on the social roles played by each one (Van’t Foort-Diepeveen et al., 2021; Eagly, 1987). Senior management is generally considered the pursuit of men, with stereotypes underlining the familiar roles that women play as mothers, wives, nurses and so on, as well as the characteristics they embody (Kaftandzieva and Nakov, 2021). Public policies and work–life balance policies refer to government regulations on equality (Marzec and Szczudlińska-Kanoś, 2023).

Career development alternatives

The literature does not provide a list of career development alternatives. Instead, these alternatives must be deduced from studies of professional success. Therefore, it is important to consider the concept of the career path to identify the alternatives for women executives in their professional development.

Professional development, at both the executive and non-executive levels, is shaped by different stages that lead people up the hierarchy. The career path refers to the different stages that individuals experience in a given profession. It can be thought of as a process that consists of exploring options and possibilities, planning actions that lead to an option and progressing in a vocational role. Women’s internal dispositions in terms of their beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions may enable or constrain their career ambitions (Mckelway, 2018).

Some authors have reported that sponsored mobility (promoted by a superior) is the predominant form of mobility in organizations (Morgan, 2017). Others have also noted that having contacts and longevity within a firm are the keys for women to access decision-making positions (O’Neil et al., 2008). In general, the literature presents the following development alternatives: internal promotion, external promotion, salary raises, entrepreneurship, remaining at the same company in the same position with the same salary, and abandoning an executive career (Eagly and Carli, 2007; Hopkins and Bilimoria, 2008; Nyberg et al., 2015; Dezsö and Ross, 2012; Pletzer et al., 2015; Doubell and Struwig, 2014, Huang et al., 2007).

The typical way for women to access high-level positions is through promotion (Eagly and Carli, 2007). Internal promotion is the most common form of promotion given that the promoted woman is already known at the company and has a certain degree of recognition (Hopkins and Bilimoria, 2008). Internal promotion is part of a decision-making process, such that women have the last word according to their personal situation (Nyberg et al., 2015).

External promotion is another alternative, although women find it harder than men (ILO, 2017). Objective measures of personal selection are being introduced, but these measures have been unable to eliminate discrimination because men are more flexible in terms of mobility (Hopkins and Bilimoria, 2008).

As a development alternative, a raise in salary is normally linked to working more hours per week. However, it is often unaccompanied by a higher position or level of responsibility. Nevertheless, it does count as an advance in professional development because it is thought of as a recognition of the worker’s role (Nyberg et al., 2015).

Another alternative is entrepreneurship (Bruni et al., 2004). The reasons that push women into entrepreneurship are the search for a work–life balance, a propensity for risk, the need to develop business skills, and the search for self-employment that offers greater financial earnings (Rey-Martí et al., 2015). The option of entrepreneurship has also been discussed from the point of view of diversity and as an alternative for the professional development of women in a liberal environment where they can better develop their leadership skills (Welter et al., 2017).

Based on this discussion, the possible alternatives for the career development of women executives are internal promotion, external promotion, entrepreneurship, salary raises and abandonment. The last of these alternatives, abandonment of an executive career, is not included in this study because it involves leaving the career path of interest. The alternative of salary raises without a corresponding increase in responsibility is also omitted from this study because it is uncommon and because a salary increase with a corresponding improvement in position within the company is covered by the alternative of internal promotion.

Hypotheses definition and analysis model

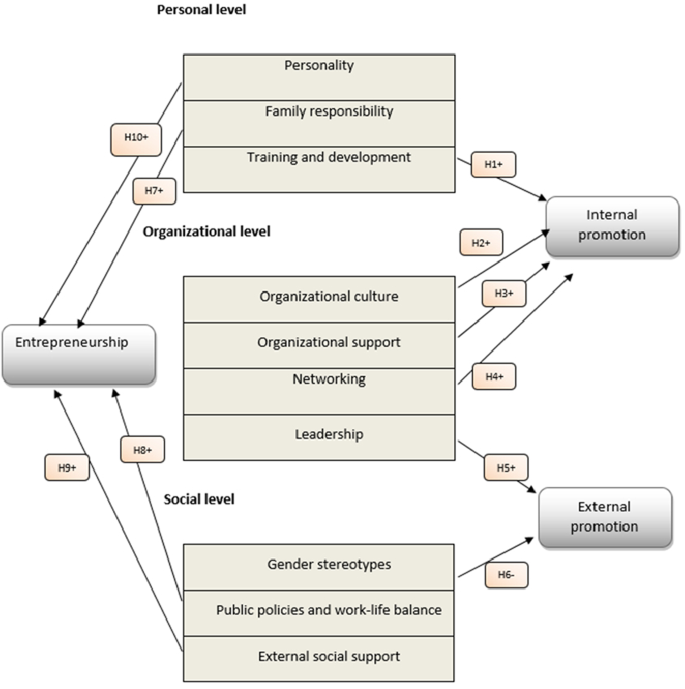

Based on the literature review and taking into account the objective of this research, Fig. 1 presents the areas of study of the basic model of analysis, which make it possible to relate the factors to the different alternatives for the development of the professional careers of women managers.

Alternatives, as reported in the literature, can be influenced by factors that favour or limit the alternative itself. Several hypotheses are therefore proposed.

Alternative internal promotion: antecedent/conditioning factors

Traditionally, one of the main reasons for the low presence of women in management has been their lack of training. However, this situation has changed in recent decades (Ridgeway, 2001; Anca and Aragón, 2007). Various international statistics show an increase in the number of women graduates in higher education, outnumbering men in many disciplines (social sciences, humanities and health) and growing in technical fields (World Economic Forum, 2022). This more specific training, which tends towards professional care and service occupations, marks horizontal occupational segregation (Halpern, 2005; Clancy, 2007) that limits access to senior management (Oakley, 2000). De Vos and De Hauw (2010) argue that education and training programmes have a direct impact on women’s success in the workplace.

In this context, women managers can be promoted internally on their own merits, based on training and development and on-the-job performance (Ng et al., 2005; Nyberg et al., 2015). It is assumed that there is a positive relationship between the training and development factor and internal promotion, which leads to Hypothesis 1.

H1. There is a positive relationship between the “training and development” factor and the “internal promotion” alternative.

A critical factor in enabling women to develop their careers is organizational fit, which is the ability to fit in and adapt to the culture of the organization (Lyness and Thompson, 2000). The most successful women are those who have managed their "organizational fit". Men, on the other hand, are more mobile and find it easier to move from organization to organization in search of higher positions (Hopkins and Bilimoria, 2008).

Organizational culture has evolved to overcome the asymmetry between men and women for managerial positions (Bilimoria and Piderit, 2007; Wajcman and Martin, 2002). The change in organizational culture has a direct impact on gender identity and pre-established roles (Kerr and Sweetman, 2003; Palermo, 2004; Dzubinski et al., 2019). In this context, the organizational culture factor may facilitate the internal promotion of women to managerial positions. This leads to Hypothesis 2.

H2. There is a positive relationship between the “organizational culture” factor and the “internal promotion” alternative.

Organizational support is the support that the organization itself gives to women, as specified in mentoring and coaching processes (Sealy and Singh, 2009), as well as the support of the immediate supervisor (Ng et al., 2005). This support provides women with greater security and confidence (Bilimoria and Piderit, 2007), which enhances their performance. In this context, women usually gain access to positions through internal promotion, after gaining the trust of the employer and the management team by demonstrating their professional value over the years (Barberá et al., 2003), given that seniority in the company is essential for a woman to gain access to a decision-making position (Oakley, 2000). Under these premises, Hypothesis 3 is proposed.

H3. There is a positive relationship between the “organizational support” factor and the “internal promotion” alternative.

Social and professional networks allow access to information and resources and facilitate career advancement (Seibert et al., 2001; Terjesen, 2005). Some authors recognize that their use facilitates faster career promotion (Dezsö and Ross, 2012).

However, the use of social and professional networks differs between men and women (Burke, 2009; Terjesen, 2005). Mainly because women generally spend less time building professional relationships with colleagues, they spend less time socializing and interacting (Eagly and Carli, 2007). In many cases, in order to balance work and private life, women reduce their working hours, take maternity leave and leave of absence, which results in fewer hours worked per year, less experience and less time to build networks. As a result, their social networks are less developed (Terjesen, 2005).

In the current environment, these networks become a factor that can drive internal promotion in women’s managerial careers. Hypothesis 4 is proposed.

H4. There is a positive relationship between the “social and professional network” factor and the “internal promotion” alternative.

Alternative external promotion: antecedent/conditioning factors

Men and women have different leadership styles (Adams and Funk, 2012; Vanderbroeck, 2010). The male leadership style is based on traits related to productivity, autonomy, independence and competition (Doherty and Eagly, 1989). For the male gender, which tends not to get carried away by emotions, the objective is results and focuses on doing, based on values such as hierarchy, individualism, competitiveness, conformism, domination and control (Barberá et al., 2003; Cuadrado and Morales, 2007).

On the other hand, women’s leadership style is based more on tasks (Vanderbroeck, 2010) and relationships (Eagly, 1987). Women are characterized by being more expressive and motivational in their leadership style, giving more empowerment to their employees (Eagly and Carli, 2007; Rincón et al., 2017). They are usually attributed to emotional characteristics and tend to favour the relationship.

Leadership is a prominent factor in explaining the professional career of women managers, both positively and negatively. Some authors recognize the positive relationship between transformational leadership style, company management and the need for ‘soft’ skills (Eagly and Carli, 2007; Hopkins and Bilimoria, 2008). The transformational style, typically feminine, is superior and offers better results in terms of efficiency, performance and satisfaction of the members of the group (Rincón et al., 2017). Others argue that since the qualities and characteristics required in managerial positions are typically masculine, women are forced to adopt the masculine leadership style in order to gain access to managerial positions and to receive consideration similar to that of men (Cuadrado and Morales, 2007; Nyberg et al., 2015).

However, more and more authors are pointing to the feminine style as a necessary leadership style for the future of business (Eagly and Carli, 2007; Hopkins and Bilimoria, 2008). Society is changing. Values such as diversity, the importance of women, the need for greater empowerment of employees, the suppression of authoritarianism in the company are being reinforced. These changes favour the female leadership factor, which has ‘soft skills’ such as emotional intelligence, intuition and empowerment (Barberá et al., 2003). Hypothesis 5 is proposed.

H5. There is a positive relationship between the “leadership” factor and the “external promotion” alternative.

External promotion is slower for women than for men (Eagly and Carli, 2007). Although objective selection measures are introduced, they often fail to eliminate gender discrimination. Gender stereotypes emerge as a central factor in the analysis of the glass ceiling (Van’t Foort-Diepeveen et al., 2021; Barberá et al., 2003). Simply by being male or female, certain roles are assigned (Sarrió et al., 2002; Schein, 2001).

Gender stereotypes influence the external promotion of women managers because they may limit people’s perceptions of women’s abilities and competencies to lead in senior management positions. Gender biases and beliefs can also limit women’s willingness to take on positions of responsibility, making it difficult for them to be promoted externally (Sarrió et al., 2002). Hypothesis 6 is proposed.

H6. There is a negative relationship between the “gender stereotype” factor and the “external promotion” alternative.

Alternative entrepreneurship: antecedent/conditioning factors

Family responsibilities include non-formal work such as domestic work, family work and caring for the elderly and dependent children. For purely natural reasons, family responsibilities fall mainly on women (O´Driscoll, 1996), which means that they often have to make great sacrifices to give up managerial positions in favour of the family (Anca and Aragón, 2007; Zabludovsky, 2007). Female managers’ careers are regularly interrupted by maternity leave, illness of children, leave for children and dependants, and even reductions in working hours. This leads to less presence of women in the company, which affects their image at the company level.

In this context, an alternative for the development of a managerial career is entrepreneurship, which allows women to run their own businesses and organize themselves, taking into account their family responsibilities. This leads to Hypothesis 7:

H7. There is a positive relationship between the “family responsibility” factor and the “entrepreneurship” alternative.

Despite the progress made in society in terms of gender equality and conciliation measures, these are not enough and there are still many difficulties for women in the workplace (Fiksenbaum et al., 2010; Fernández-Crehuet et al., 2016). The development of public policies and work–life balance is essential (Marzec and Szczudlińska-Kanoś, 2023). Maternity leave or the possibility of taking leave or reducing working hours is not enough. There is a need for measures that do not harm women in terms of time and form, such as teleworking and flexible working hours (Fernández-Crehuet et al., 2016). Government initiatives in the form of legislation are needed to promote women’s access to managerial positions, as social change is evident and policies need to adapt to it (Kilday et al., 2009; Coffman et al., 2010).

Many of these policies and actions are related to entrepreneurship (Alameda Castillo, 2017). And women opt for entrepreneurship in search of a better work–life balance (Welter et al., 2017). Hypothesis 8 is proposed.

H8. There is a positive relationship between the “public policies and work-life balance” factor and the “entrepreneurship” alternative.

External support is the independent support of the woman’s direct relationships in the firm. It is the general support that society can provide, usually through associations, groups and pressure groups (Palermo, 2004).

These associations or groups set up for women’s development can exert greater pressure on the essential terms of negotiations with governments on legislation, or they can jointly propose alternatives or new measures in the economic sphere, all of which exert greater pressure (Kerr and Sweetman, 2003). The various social initiatives thus promote women’s access to managerial positions, often through entrepreneurship (Kilday et al., 2009; Coffman et al., 2010). It is true that society is increasingly promoting female entrepreneurship. It is therefore the external–social support factor. Based on this, the relationship between the external–social support factor and the entrepreneurship alternative is considered positive. Hypothesis 9 is proposed.

H9. There is a positive relationship between the “external support” factor and the “entrepreneurship” alternative.

Internal personality factors are often linked to cultural, religious, socio-economic and political beliefs (Cubillo and Brown, 2003). For women in the workplace, low self-esteem, fear of failure and lack of competitiveness are often identified as internal limiting factors (Oplatka, 2006) that hold back the careers of women managers (Anca and Aragón, 2007; Hopkins and Bilimoria, 2008). On the other hand, the will to serve and the sense of duty are linked to an entrepreneurial orientation.

Entrepreneurship provides personal satisfaction for women (Burt and Raider, 2002). The literature suggests that women receive a greater "return" for their qualities and skills in self-employment than in a salaried position (Devine, 1994). Several studies report how senior women leave multinational companies to start their own businesses (Terjesen, 2005). Hypothesis 10 is posed.

H10. There is a positive relationship between the “internal personality” factor and the “entrepreneurship” alternative.

Once hypotheses are defined, Fig. 2 shows the complete graphical representation of the basic analysis model including hypotheses.

Method

This study addresses the question of how women choose career alternatives considering a set of criteria reflecting social, personal, and organizational issues. The study considers the scenarios that women executives commonly face when seeking to advance their careers. The aim is to obtain rankings of preferred alternatives for career development in each scenario. Each of these scenarios implies giving different importance (different values to the weights reflecting the importance) to each of the 10 factors of women’s career development considered. It is very important to remark that these factors are usually in conflict. So, we want to produce a recommendation for women for career alternatives to choose from considering conflictual criteria for each one of the five scenarios considered. We will face five multi-criteria decision aid (MCDA) problems, one for each scenario. The factors will be considered the criteria and the career alternatives will be the alternatives. Weights for the criteria will be different for each scenario.

There are numerous multi-criteria decision aid methods. Therefore, we will have to justify the rationale for the chosen method. The factors of women’s career development are considered an attempt to reflect the social, personal, and organizational viewpoints that are relevant in deciding on one career alternative or another. The way in which these factors have been chosen allows us to affirm that they constitute a coherent family of criteria in the sense defined by Roy and Bouyssou (1993). Another important consideration is the fact that it seemed relevant to us that the criteria should not compensate for each other (a low performance on a personal criterion should not be compensated by a good performance on a social criterion, for example). We have chosen ELECTRE methods (Roy and Bouyssou, 1993) as a family of methods suitable for our study. Different are the problematics dealt with by these methods. As our problem deals with the ranking problematic, we will choose the ELECTRE III method (Figueira et al., 2016; Greco et al., 2016). To learn more about multi-criteria decision methods for the ranking problematic see Taherdoost and Madanchian (2023).

Let us see precisely why we have chosen the ELECTRE III method. Recall that our objective is to obtain a ranking of the alternatives. Well, to choose which method, among the possible ones that generate a ranking as a final recommendation, we will consider the scheme proposed by Roy and Slowinski (2013). According to them the first question to ask when choosing a multi-criteria decision-aiding method is the following: “Taking into account the context of the decision process, what type(s) of results is the method expected to produce, so as to allow the elaboration of relevant answers to the questions posed by the decision maker?”. The answer given by the authors is that there are four possible types:

-

a.

“Type 1: A numerical value (utility, score) is assigned to each potential action.”

-

b.

“Type 2: The set of actions is ranked (without associating a numerical value to each of them) as a complete or partial weak order.”

-

c.

“Type 3: A subset of actions, as small as possible, is selected in view of a final choice of one or, at first, few actions.”

-

d.

“Type 4: Each action is assigned to one or several categories, given that the set of categories has been defined a priori.”

In our case, the expected outcome is clearly type 2. We do not consider it necessary, or even interesting, to assign a numerical value to each alternative. There is one restriction to bear in mind, and that is that this type of outcome can only be considered if the set A of possible actions is known a priori, which is our case.

The methods relevant here, and for which software is readily available, are ELECTRE III, IV (Figueira et al., 2016), PROMETHEE I and II (Brans and Mareschal, 2005), all robust ordinal regression methods (Greco et al., 2010) producing necessary and possible rankings (like UTAGMS, GRIP, extreme ranking analysis, RUTA, ELECTREGKMS and PROMETHEEGKMS).

As mentioned above, we do not want the chosen method to allow for trade-offs or compensation between criteria. The methods that rely on aggregating criteria into a synthetic criterion and assigning a numerical value (utility, score) are compensatory methods. Methods based on outranking relationships allow very limited compensation under certain conditions. In view of this, our choice is between the ELECTRE or PROMETHEE methods, which produce a ranking of alternatives as a final recommendation.

In addition, it is desirable to avoid complex information for the decision-maker. PROMETHEE requires the definition of a preference function associated with each criterion, while ELECTRE requires a set of parameters to model the preference information. In our case, the introduction of parameters to model preference information was much better understood by the decision-maker than the definition of preference functions. Therefore, we decided to use the ELECTRE method. As the introduction of weights was also essential, ELECTRE III was chosen.

The construction of the MCDA model was based on a constructivist approach. Both the construction of the coherent family of criteria and the set of alternatives have been carried out based on the existing literature. No cause-and-effect relationships are assumed between the components of the model. The aim is to obtain a ranking of preferences among the career alternatives considering the family of criteria and the importance (weights) that these criteria have in each of the five scenarios considered.

Data

The data were gathered from a survey (see Supplementary Material). Table 1 presents the technical details.

Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of the women included in the survey.

Respondents were asked to rate (considering 1 not at all, 2 a little, 3 a little, 4 a lot and 5 completely) three possible career choices, plus a fourth (“other”) related to access to public employment or a family business, on the basis of the factors described in the literature. The alternatives for career development were internal promotion (IP), external promotion (EP), entrepreneurship (EN) and other (OT). The factors under consideration were internal factors (IF), family responsibility (FR), training and development (T&D), leadership (LD), organizational culture (OC), organizational support (OS), social and professional network (NT), external social support (ES), gender stereotypes (GS), and public policy and work–life balance (PP).

The survey was supported by data from in-depth interviews with 25 women managers who had already responded to the questionnaire. The aim of the interviews was to obtain qualitative data to enrich and add detail to the study. The interviews also helped explain and support some of the study’s findings.

These 25 women had different profiles in terms of age, children, training, type of company, position, and the way they reached their position. The aim was to interview women with different characteristics to explain the range of contexts that women experience. Of these 25 women, 10 were aged 30–40 years, 10 were aged 40–50 years and five were older than 50 years. Regarding children, 18 had children (12 had more than one child) and seven had no children. All except four of them had a higher education degree. Those four had completed their secondary education. All of the interviewed women worked in service sector companies in first-line positions (11 of the 25 women), middle-line positions (five women) and top management positions (nine women). Finally, 14 had been promoted internally, five had been promoted externally, and six had reached their position through entrepreneurship.

Method: ELECTRE III

ELECTRE methods are a family of multicriteria decision-aiding methods (MCDA) based on outranking relations. ELECTRE III is focused on ranking problems Alternatives (possible career choices in this study) are ordered from best to worst through pairwise comparison (Figueira et al., 2016; Greco et al., 2016).

The basic elements of any multicriteria decision-aiding problem are a set of alternatives, a coherent family of criteria, a performance matrix of criteria for each of the alternatives and a set of criteria weights. ELECTRE methods are based on the use of binary relationships called outranking relations. An alternative a outranking an alternative b (denoted by a S b) expresses the fact that there are sufficient arguments to decide that a is at least as good as b and there are no essential reasons to refute this (Roy and Bouyssou, 1993). An outranking degree S(a,b) between a and b is computed to measure or evaluate this assertion. These outranking relations are based on three basic binary relations: preference, indifference and incomparability.

ELECTRE methods are based on the principles of concordance and discordance. The concordance principle states that if a is demonstrably as good as or better than b according to a sufficiently large weight of criteria, then it is considered to be evidence in favour of a outranking b. The discordance principle states that if b is very strongly preferred to a on one or more criteria, then it is considered to be evidence against a outranking b.

ELECTRE III is divided into two phases. First, the outranking relationship between the alternatives is constructed and then exploited. To construct the outranking relationship, use other parameters to model the decision maker’s preferences, in addition to the criteria weights. These parameters are the preference, indifference and veto thresholds. Criteria can be increasing or decreasing.

The indifference threshold indicates the largest difference between the alternatives’ performance on a given criterion that makes the two levels of performance indifferent to the decision maker. The preference threshold indicates the largest difference between the performance of the two alternatives such that one is preferred over the other for the criterion under consideration. The veto threshold for a criterion is the difference between the performance of the two alternatives above which it seems reasonable to reject any credibility about the outranking of one alternative by the other alternative, even when all other criteria are in line with this outranking.

ELECTRE III constructs a partial concordance index for each criterion, an overall concordance index and a discordance index. Once these indices have been defined, the credibility index can be defined. The partial concordance index measures the strength of support, given the available evidence, that a is at least as good as b considering one specific criterion. The overall concordance index measures the strength of support, given the available evidence, that a is at least as good as b considering all criteria. For each criterion, the discordance index measures the strength of the evidence against the hypothesis that a is at least as good as b. The credibility index measures the strength of the claim that “alternative a is at least as good as alternative b”. If no veto thresholds are specified, the credibility index is equal to the overall concordance index for all pairs of alternatives.

The second phase of ELECTRE III consists of the exploitation of the pairwise outranking indices through bottom-up and top-down distillations. The distillation procedures each calculate a complete pre-order. Each pre-order considers the behaviour of each alternative when outranking or being outranked by the other alternatives. These two procedures can lead to two different complete pre-orders. The final partial pre-order is the intersection of these two complete pre-orders (Figueira et al., 2016).

Results

The aim is to obtain a ranking of career alternatives for women according to the 10 factors (personal, organizational and social factors, see Fig. 2) considered in this study. Different scenarios are presented, and rankings are proposed for each scenario.

For the multicriteria decision problem, the median of the ratings that respondents gave to each alternative under each criterion was taken. These ratings are shown in Table 3, which is referred to as the table of performance of the alternatives in the multicriteria decision problem.

The questionnaire also asked women about the importance they attached to each of the 10 factors considered in the study. The weights of the criteria were calculated from the results of the survey. To assign weights to the criteria, five scenarios were considered. These five scenarios generated five multicriteria decision problems and consequently five rankings of the professional alternatives. The five scenarios are now described.

Scenario 1: Professional development

In this scenario, women fight for their professional development at all costs. For these women, their professional goal is to improve, reach the highest possible position based on their potential and take on ever greater responsibility. These women generally make considerable sacrifices in their personal life.

Scenario 2: Job stability

In this scenario, women pursue job stability. There comes a time when they do not so much want a promotion as to be stable in their current management position. They neither look for change nor show ambition.

Scenario 3: Family

In this scenario, women prioritize family. These women managers see their family as the most important thing and believe that it comes before everything else. They are not willing to miss out on work-life balance measures. If they have to give up their professional career, they will do so.

Scenario 4: Family and professional development

In this scenario, women pursue their professional development without giving up their family life. For these women, although family comes before everything else, they never give up their professional development, but instead try to balance this area of their life with their family.

Scenario 5: Equality

In this scenario, women have a professional goal to demonstrate the equality of genders. In other words, they wish to demonstrate women’s ability to hold managerial positions.

First, to weight the criteria (factors), the weights must be established according to the decision maker’s situation and priorities and therefore for each scenario. From the questionnaires, a different weighting was obtained for each factor taking into account the five scenarios. Each respondent indicated the particular scenario she was facing. Of the 236 women who responded, 92 declared themselves to be in Scenario 1 (professional development), 21 in Scenario 2 (job stability), 26 in Scenario 3 (family), 62 in Scenario 4 (family and professional development) and 35 in Scenario 5 (equality). From 1 to 10, respondents rated the importance of the factors in their specific scenario. The 25 interviews were then used to find a generic explanation for these weightings. In the statistical analysis, the weighted average of the importance of factors for each scenario was used to give the weights.

The software Diviz was used to compute the rankings in the ELECTRE III method (Meyer and Bigaret, 2012; Ishizaka and Nemery, 2013). For each of the five scenarios, Table 4 shows the weights of the criteria (factors) and the results in the form of a ranking of the alternatives proposed. It was considered unnecessary to introduce thresholds or vetoes due to the scales used in the performance table.

Each factor has a high degree of importance in at least one of the scenarios. Table 5 summarizes the scenarios, factors and results provided by ELECTRE III, enabling testing of the hypotheses corresponding to the analysis model.

Of the proposed hypotheses, H1–H4 cannot be confirmed, but the rest are supported. For each hypothesis, the factor is examined, and the scenario for which the factor has the highest weight is chosen. This information is then compared with the results from the ELECTRE III method. For example, H1 proposes a positive link between the factor “training and development” and the alternative “internal promotion”. Given that the factor under examination is training and development, the scenario where this factor has the highest weighting is chosen. In this case, the chosen scenario is Scenario 1 (where women prioritize their professional development over all else). The results of the ELECTRE III method suggest that for this factor, the preferred alternative is “entrepreneurship”, with “other” in second place. In third place is “external promotion” and finally “internal promotion”. Therefore, the first hypothesis is not confirmed. This procedure is repeated for all hypotheses, giving the results shown in the right-hand column of Table 5.

Discussion

This section discusses the results and links them back to the literature. The intention is for the results to support the general idea that for women, career advancement into senior positions is difficult. “The ubiquitous work/family narrative, and the associated ‘choices’ a woman may make about her work life, provide only a small explanation for why women’s career progression tends to be slower than that of men” (Jogulu and Franken, 2022, p. 3).

In relation to the first hypothesis, the results are not consistent with the literature. According to Ng et al. (2005) and Nyberg et al. (2015), internal promotion is directly linked to women’s education and training. In the present study, women reported that for internal promotion, the most influential factor is training and development (Scenario 1). However, as shown by the weightings of the factors when the priority is professional development (Scenario 1), the preferred alternative is entrepreneurship (results from ELECTRE III). Training and development can be a motivating factor, as women are increasingly trained in higher education, but it can also be a limiting factor, as it confines them to certain areas where there is a greater female presence, distancing them from others, especially technical areas (Oakley, 2000). Although nowadays, it is believed that women are just as well or better trained than men, especially in certain areas (Clancy, 2007) and that this factor is a motivator for their professional careers. But when women prioritize their professional development, they have to seek promotion on their own. So, for women with strong training, the preferred development alternative is entrepreneurship, because it gives them greater personal satisfaction (Brush, 2006) and autonomy.

In relation to the second hypothesis, the results also contradict the literature, which describes a positive relationship between the factor “organizational culture” and internal promotion. For a woman executive to choose internal promotion within her firm, she should fit into its culture. Experts refer to this phenomenon as organizational fit (Lyness and Thompson, 2000). The results contradict this argument. One explanation might be that the dominant organizational culture within companies is still highly traditional, in the sense that it still places women in the role of mothers (Lee et al., 2006) and identifies women in positions destined to serve and care for people. In many cases, women are confined to positions that limit their development. (Sullivan and Mainiero, 2008; Godoy and Mladinic, 2009).

Another possible argument is that organizational culture is detrimental to women’s internal promotion because of the prevalence of presenteeism (Barberá et al., 2003). Presenteeism is prevalent in today’s organizations (Van’t Foort-Diepeveen et al., 2021). Professional work, especially managerial work, requires great dedication. Thus, a greater presence in the company is linked to greater participation in decision-making, which is a necessary factor for promotion (Nyberg et al., 2015). Men are more visible, dedicate more time and effort to the company and are therefore considered more for promotions (Zabludovsky, 2007). Therefore, if the woman spends less time in the company due to the factor of family responsibilities, she will be less visible for internal promotion.

In many organizations, the dominant culture is patriarchal and generates asymmetries between men and women (Barberá et al., 2003; Dzubinski et al., 2019). Most authors support the thesis that organizational culture is dominated by androcentric values that exclude the feminine (Pallares and Martínez, 1993; Bilimoria and Piderit, 2007). In this culture, most managerial positions are held by men. Therefore, there is an influence on the gender of the people who make decisions about internal promotion in organizations (Cuadrado and Morales, 2007). However, organizations are not aware that organizational culture acts as an obstacle for women and perpetuates unequal relations between men and women, so they do not see the need for institutional action to alleviate this situation (Zabludovsky, 2007).

When faced with a highly traditional organizational culture, women prefer the alternative “other”, which covers family businesses and public employment. This alternative lets them escape from a culture where femininity can exclude them from being promoted.

For the third hypothesis, the results contradict the literature, which describes a positive relationship between organizational support and internal promotion. Through processes of mentoring, coaching, training and support from superiors, organizational support provides women with feedback on their personality and good work, giving them greater belief and confidence (Bilimoria and Piderit, 2007; De Vos and De Hauw, 2010). The explanation for this finding may be the lack of transparency and information in promotion processes (Oakley, 2000). The empirical analysis does not confirm the relationship between internal promotion and organizational support to the extent that internal promotion is not the preferred alternative. Instead, women with organizational support prefer the alternative “other”. Accordingly, when women feel supported and attain a certain level of belief and confidence, they prefer to develop their careers on their own, without having to rely on promotion processes.

The positive association between the factor “social and professional network” and the alternative “internal promotion” is not confirmed. This finding contradicts the literature, which cites social and professional networks as a factor that enables faster promotion by providing access to information, better resources and more valuable contacts (Burke, 2009). This finding could be explained by the fact that once a woman establishes a network of contacts, it gives her greater mobility to follow other alternatives to support her professional development, such as entrepreneurship or external promotion. Moreover, networks have always been the domain of men (Simpson, 2000). Men devote more time to building a broad network of contacts because their careers are not usually interrupted by maternity or leaves of absence (Eagly and Carli, 2007). Thus, when women can develop a strong contact network, the preferred alternative is entrepreneurship instead of internal promotion.

Not all the hypotheses raised in relation to internal promotion were tested. It seems that at a theoretical level, the literature suggests positive relationships between factors such as organizational culture, training and development, organizational support, social and professional networks; but in the study, women do not opt for internal promotion in the presence of these factors but choose other career development alternatives such as entrepreneurship or others. In general, women feel that they have fewer opportunities for career development than men (Ohlott et al., 1994), and even that they are given less consideration (Hopkins and Bilimoria, 2008). This is explained by the organizational culture, where masculine values persist, and by stereotyped gender beliefs so that women with children are seen as women who will not work full time, who will have to ask for more days for their own affairs, or even leave. And women without children, far from being more valued or considered, are seen as potential mothers. As a result, women, whether they have children or not, receive less attention in terms of training, networking and organizational support, resulting in fewer opportunities for internal promotion. (Cuadrado and Morales, 2007).

ELECTRE III confirms the positive relationship between the factor “leadership” and the alternative “external promotion”. This finding is consistent with the literature. Although some authors have reported that a feminine leadership style hinders progress in professional development (Adams and Funk, 2012; Eagly and Karau, 2002), the majority have noted the need for this type of leadership in order to bring new values to the business world (Eadly and Carli, 2007; Hopkins and Bilimoria, 2008). Nowadays, selection processes are designed to look for capabilities and styles based on soft skills, which women tend to have. Thus, feminine leadership is a strength of new organizations (Terjesen et al., 2009), surpassing the "think manager-think male" coined by Schein in 1973. Consequently, the empirical analysis confirms that the preferred alternative for women is external promotion. Once they see that the market values their leadership and qualities, women choose to change companies.

The results confirm a negative relationship between the factor “gender stereotypes” and the alternative “external promotion”. This finding is consistent with the literature. Women find it harder to pass standard selection processes, despite efforts to introduce objective measures that eliminate gender discrimination. Gender stereotypes exert a negative influence on external promotion. This factor is the main argument in relation to the glass ceiling (Agars, 2004). The characteristics of women—their role as women and mothers, which ties them to domestic and family duties—keep them from developing professionally (Legault and Chasserio, 2003). Although there have been significant changes in the role of women in society in recent decades, gender stereotypes still persist (Baron and Byrne, 2005) and women are aware that gender stereotypes can create a barrier to external promotion.

One of the most serious consequences of this factor, in addition to preventing normal access to managerial positions, is employment discrimination against women in all its aspects; from the point of view of pay and from the point of view of sexual and psychological harassment (Alcover, 2004; Berryman-Fink, 2001; Leymann, 1990). Studies show that men are favoured over women and that women actually experience more precarious pay conditions, more atypical working hours and a lack of pay equity compared to men (Eagly and Carli, 2007; Oakley, 2000).

The positive link between the factor “family responsibility” and the alternative “entrepreneurship” is confirmed, in line with the literature. Family responsibility refers to informal work, such as domestic duties, housework, caring for the family, and looking after children and dependent adults. These tasks predominantly fall to women, who are socially obliged to play a double reproductive and productive role (O´Driscoll, 1996). So, Many authors see family responsibilities as the main obstacle women face in developing their managerial careers (Cuadrado and Morales, 2007; Sarrió et al., 2002; Eagly and Carli, 2007). Even a growing number of women are postponing or abandoning their plans for maternity to focus on their professional development (Zabludovsky, 2007). Entrepreneurship offers a solution to this problem, and it is the alternative that best favours women’s professional development. For women, the priority is to find a balance (Eagly and Carli, 2007). This means that in order to fulfil their family responsibilities and at the same time focus on their professional development, they start their own business, run the family business or study to enter the public sector in order to balance work with other aspects of their lives.

The positive relationship between the factor “public policies and work–life balance” and the alternative “entrepreneurship” is confirmed. Despite a growing number of public policies aimed at ensuring a balance between professional and family life, women prefer to start their own businesses in a way that is compatible with their family life (Brusch, 2006). The literature points to the need for greater development of public policies and conciliation (Selva et al., 2011). There are many proposals at international and national levels and few actions that are implemented (Fernández-Crehuet et al., 2016). In the absence of public policies and conciliation that favour new measures to reconcile personal/family life with work, women prefer to start their own businesses in an organized way according to their family life. Therefore, the result of directly linking this factor to entrepreneurship is in accordance with the literature.

The positive link between the factor “external support” and the alternative “entrepreneurship” is confirmed. This finding is consistent with the literature, which highlights the role of legal, government and social support in ensuring a high presence of women entrepreneurship (Kilday et al., 2009; Coffman et al., 2010). In addition, the existence of associations that support women in the adventure of entrepreneurship, as well as specific university and financial programmes, favour entrepreneurship (Palermo, 2004).

The positive link between the factor “personality” and the alternative “entrepreneurship” is confirmed, in line with the literature, to the extent that it links self-esteem and confidence to entrepreneurship (Nikolova, 2019; Devine, 1994; De Vos and De Hauw, 2010). According to the literature, women leave multinationals to start their own businesses given the difficulties they face in professional development within the world of paid employment (Terjesen, 2005).

However, the results for the relationship between personality and “external promotion” or “other” (as equivalence is given), are not consistent with the literature. There is a female evasion in work situations, giving priority to the personal life over the professional life, because of the fear of being successful in the professional field and the confrontation that this might entail. This is the example of those women who, with a high academic background and the possibility of opting for top management positions, opt for intermediate positions, refusing promotion or external promotion (Díez-Gutiérrez et al., 2009).

ELECTRE III provides a solution in situations where there are equal weightings or when all factors are considered equally important. Accordingly, the preferred alternatives for women executives are, first, external promotion, entrepreneurship and “other” (with equivalent scores), followed by internal promotion. This result is surprising because the majority of women who responded to the questionnaire indicated that they had reached their current position through internal promotion (60%). However, ELECTRE III identified the preferred alternatives by women in each scenario while considering the importance that the women assigned to the factors. In this study, it is important to differentiate between reality and women’s views on the importance of each factor in each scenario. That is, one thing is what women actually experience and another is how they would like to live or what alternative they would prefer in each scenario.

The solutions provided by ELECTRE III do not disregard any alternative. Instead, they show that some alternatives are preferable to others. In this case, internal promotion is the least preferred alternative by women in all scenarios, including the solution where all factors are considered to be equally important. In the current context, internal promotion is not the easiest option for women. If women wish to continue to advance, they have to do so in another company or by starting their own firm.

Conclusions

This study examines a topic of considerable academic, social and economic interest. Specifically, it explores the factors of career development of women executives in relation to the alternatives available to them for that development. The study is based on multicriteria decision techniques. It covers a gap in the literature, where this topic is addressed from a theoretical perspective.

The analysis of factors and development alternatives shows that women do not reach executive positions in the same way as men. When they manage to break the glass ceiling, they are under pressure and at a disadvantage with respect to their male peers. One in four women has postponed maternity, and one in five acknowledges having decided not to have children due to difficulties in professional development at the executive level (Eurofound, 2016). For a series of reasons, women executives feel forced to make greater personal and professional efforts than men.

The results of the present study provide some highly interesting conclusions. Crucially, each woman finds herself in a unique personal situation, which differs from that of others. Therefore, the method applied in this study enabled the analysis of a series of scenarios. In each scenario, the factors were weighted differently, and depending on the scenario, the relationships with the alternatives also varied. The results show how each factor affects the alternatives differently in each scenario.

In Scenario 1, professional development is the priority for women executives. The factors “training and development” and “social and professional network” exert a direct influence on the alternative “entrepreneurship”. In this scenario, when women have extensive training and experience and a broad contact network, their preferred alternative for career development is entrepreneurship.

In Scenario 2, stability at work is the priority for women executives. The factors “organizational culture” and “organizational support” exert a direct influence on the alternatives “other” and entrepreneurship. Women executives that seek professional stability choose to start a business or take exams to enter public employment.

In Scenario 3, women seek a balance between their family and their professional development, although they are prepared to forgo this development in favour of their family. The factor “family responsibility” is the key factor in choosing the alternative “other” or entrepreneurship.

In Scenario 4, women seek a balance between family and work without forgoing their careers. The factors that determine the choice of entrepreneurship, external promotion and “other” (to the same degree) are “public policies and work–life balance”, social and external support, and personality.

Finally, in Scenario 5, women seek to demonstrate that both genders are equal. In this case, the factors that determine their preference for external promotion, entrepreneurship and “other” as alternatives for career development are “leadership”, “gender stereotypes” and “public policies and work–life balance”.

Notably, no factor determined that internal promotion would be the preferred career development alternative for women executives. This finding may be related to organizational culture, organizational support and networking. In practice, women view organizational culture as a barrier to their professional development. Presenteeism is still a dominant force for executives seeking promotion, and for biological reasons, men are more visible in this sense. Regarding organizational support, only 36.2% of the surveyed women reported having the support of a mentor. The figure of the mentor provides support for promotions within the firm. Likewise, although contact networks are important for internal promotion, the questionnaire responses suggest that only a minority of women use contact networks often or very often.

The analysis reveals women’s need to take control of their own professional development. That is, for most factors, the preferred alternative for career development is entrepreneurship. This finding means that women have a major need to develop on their own terms, with their own means, without having to rely on a company that may hold them back. Thanks to their qualities, women are perfectly capable of running their own businesses and possess the key aptitudes needed for success.

In conclusion, this study shows that women find themselves in unique situations and have different priorities. They feel most satisfied and have a stronger predisposition to start a business. Internal promotion is not their preferred alternative in any scenario, regardless of the importance assigned to certain factors. It seems that there is still much to be done in organizations to place women on an equal footing with men for internal promotions (Sommer, 2022).

This study contributes to the literature on the topic of gender in management in terms of the theoretical foundations of the glass ceiling and empirical validation of the theory. Thus, as a theoretical contribution, it allows us to respond to specific links between factors and career development alternatives of women executives, filling this gap in the literature on the glass ceiling. Through this research, we will try to better understand this phenomenon by considering both factors and alternatives. The model proposed by Elacqua et al. (2009) is enriched. Another contribution is related to the application of multicriteria decision techniques, not used in this type of analysis. It also has managerial implications that give companies an empirical basis regarding the focus on women’s career development.

The implications of this research for practice and society are significant. First, by providing knowledge about the glass ceiling that negatively impacts women’s individual career development, opportunities for promotion and recognition of their skills, talents and contributions can be promoted.

Secondly, knowledge of the positive relationship between factors and alternatives in the development of a woman manager’s career will help to avoid perpetuating gender inequality, increase diversity in leadership roles and promote the potential for innovation and progress. By including women in the pool of candidates for top positions, organizations do not miss out on the diverse perspectives, experiences and insights that can drive innovation and creativity. This responds to Bullough et al., (2017) call for new research on the barriers and biases faced by women in leadership: it could aim to provide specific, evidence-based recommendations on how organizations and individuals can work to develop greater gender diversity in leadership and senior positions around the world.

Third, to break the glass ceiling, organizations need to take proactive steps to promote gender equality and diversity in their recruitment, retention and promotion practices. This can include implementing policies and initiatives to support work–life balance, providing training and mentoring opportunities, and addressing unconscious biases and stereotypes that may limit women’s advancement. At a societal level, tackling the glass ceiling requires a broader commitment to gender equality, including addressing issues such as unequal pay, lack of access to education and training, and gender discrimination and harassment. This requires a concerted effort by policymakers, business leaders and individuals to promote greater gender equality and create a more inclusive society where all individuals have equal opportunities to succeed.

Given the importance of the above implications, future lines of research in the area of the glass ceiling aim to develop a deeper understanding of the factors that contribute to gender inequality in the workplace and to identify strategies that can help promote greater gender equality and diversity. Another interesting line of future research is to analyse spatial differences in terms of the relationship between determining factors and alternatives for women’s career development; taking into account specific factors may lead to interesting conclusions in those countries where women’s career development is most favoured. Indeed, the inclusion of outcome variables (such as job satisfaction, well-being, organizational performance and innovation) will broaden the scope towards the consequences of the glass ceiling; research in this area seeks to understand the impact of the glass ceiling on individuals, organizations and society as a whole.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available as a form of supplementary file and/or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Van ’t Foort-Diepeveen RA, Argyrou A, Lambooy T (2021) Holistic and integrative review into the barriers to women’s advancement to the corporate top in Europe. Gend Manag 36(4):464–481. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-02-2020-0058

Ackah C, Heaton N(2003) Human resource management careers: different paths for men and women Career Dev Int 8:134–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430310471041

Adams RB, Funk P (2012) Beyond the glass ceiling: does gender matter? Manag Sci 58:219–235. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41406385

Agars MD (2004) Reconsidering the impact of gender stereotypes on the advancement of women in organizations. Psychol Women 28:103–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00127.x

Akpinar-Sposito C (2013) Career barriers for women executives and the glass ceiling syndrome: the case study comparison between French and Turkish women executives. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 75:488–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.04.053

Alameda Castillo MT (2017) Entrepreneurship in women: difficulties in terms of work-family reconciliation and self-employment (advances and setbacks). In: Collective bargaining as a vehicle for the effective implementation of equality measures. Universidad Carlos III, Madrid, Getafe, pp. 142–161

Alcover CM (2004) Gestión del bienestar laboral. In: Alcover CM et al (eds) Introducción a la Psicología del Trabajo. McGraw Hill, Madrid, pp. 543–490

Anca C, Aragón S (2007) La mujer directiva en España: catalizadores e inhibidores en las decisiones de trayectoria profesional. Acad Rev Latinoam Admin 38:45–63

Babic A, Hansez I (2021) The glass ceiling for women managers: antecedents and consequences for work–family interface and well-being at work. Front Psychol 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.618250

Barberá E, López AR, Catalá MTS (2003) Mujeres directivas, espacio de poder y relaciones de género. Anu Psicol/UB J Psychol 267–278 https://raco.cat/index.php/AnuarioPsicologia/article/view/61740

Barnett RC (2004) Preface: women and work: where are we, where did we come from, and where are we going. J Soc Issues 60:667–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00378.x

Baron RA, Byrne D (2005) Prejuicio: causas, efectos y formas de contrarrestarlo. In: Baron and Byrne (eds) Psicología social. Pearson Prentice-Hall, Pearson Educación, Madrid, pp. 215–261

Bendl R, Schmidt A (2010) From ‘glass ceilings’ to ‘firewalls’- different metaphors for describing discrimination: from ‘glass ceilings’ to ‘firewalls’. Gend Work Organ 17:612–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00520.x

Berryman-Fink C (2001) Women’s responses to sexual harassment at work: organizational policy versus employee practice. Employ Relat Today 27:57–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/ert.3910270407

Bilimoria D, Piderit SK (2007) Handbook on women in business and management. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Brans JP, Mareschal B (2005) Promethee methods. In: Figueira J, Greco S, Ehrgott M (eds) Multiple criteria decision analysis: state of the art surveys. Springer, pp. 163–185

Bruni A, Gherardi S, Poggio B (2004) Entrepreneur mentality, gender and the study of women entrepreneurs. J Organ Change Manag 17:256–268

Brush CG (2006) Women entrepreneurs: a research overview. In: Casson M (ed) The Oxford handbook of entrepreneurship. Oxford Publishing, London, pp. 661–628

Bullough A, Moore F, Kalafatoglu T (2017) Research on women in international business and management: then, now, and next. Cross Cult Strateg Manag 24:211–230. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-02-2017-0011

Burke RJ (2009) Cultural values and women’s work and career experiences. In: Bhagat, Steers (eds) Handbook of culture, organizations and work. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 442–461

Burt RS, Raider HJ (2002) Creating careers: Women’s paths to entrepreneurship. Unpublished manuscript. University of Chicago, Chicago

Clancy S (2007) ¿Por qué no hay más mujeres en la cima de la escala corporativa: debido a estereotipos, a diferencias biológicas o a elecciones personales. Rev Latinoam Adm 38:1–8

Coffman J, Gadiesh O, Miller W (2010) The great disappearing act: gender parity up the corporate ladder. Boston Bain & Company, Boston

Cohen JR, Dalton DW, Holder-Webb LL, Mcmillan JJ (2020) An analysis of glass ceiling perceptions in the accounting profession”. J Bus Ethics 164:17–38

Cotter DA, Hermsen JM, Ovadia S, Vanneman R (2001) The glass ceiling effect. Soc Forces 80:655–681. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2001.0091

Cuadrado I, Morales JF (2007) Algunas claves sobre el techo de cristal en las organizaciones. Rev Psicol Trab las Organ 23:183–202

Cubillo L, Brown M (2003) Women into educational leadership and management: international differences? J Educ Adm 41:278–291

De Vos A, De Hauw S (2010) Linking competency development to career success: exploring the mediating role of employability. Vlerick Leuven Gent Management School Working Paper Series 2010-03. Vlerick Leuven Gent Management School

Devine F (1994) Segregation and supply: preferences and plans among ‘self-made. Work Organ 1:94–109

Dezsö CL, Ross DG (2012) Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation. Strateg Manag J 33:1072–1089. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1955

Díez-Gutiérrez EJ, Terrón-Bañuelos E, Anguita-Martínez R (2009) Percepción de las mujeres sobre el "techo de cristal" en educación. Rev Interuniv Form Profr 23(1):27–40. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=27418821003

Doherty EG, Eagly AH (1989) Sex differences in social behavior: a social-role interpretation. Contemp Sociol 18:343. https://doi.org/10.2307/2073813

Doubell M, Struwig M (2014) Perceptions of factors influencing career success of professional and business women in South Africa. S Afr J Econ Manag Sci 17:531–543

Dzubinski L, Diehl A, Taylor M (2019) Women’s ways of leading: the environmental effect. Gend Manag 34(3):233–250. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-11-2017-0150

Eagly AH, Karau SJ (2002) Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol Rev 109:573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573

Eagly AH, Carli LL (2007) Women and the labyrinth of leadership. Harv Bus Rev 85(62–71):146

Eagly AH (1987) Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-role interpretation. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203781906

Elacqua TC, Beehr TA, Hansen CP, Webster J (2009) Managers’ beliefs about the glass ceiling: interpersonal and organizational factors. Psychol Women 33:285–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/036168430903300304

Eurofound (2016) The gender employment gap: challenges and solutions. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/the-gender-employment-gap-challenges-and-solutions. Accessed 12 Jul 2022

Fagenson EA (1990) At the heart of women in management research: theoretical and methodological approaches and their biases. J Bus Ethics 9:267–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00380326

Fernández-Crehuet JM, Gimenez-Nadal JI, Reyes-Recio LE (2016) The national work–life balance index©: the European case. Soc Indic Res 128:341–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1034-2

Figueira JR, Mousseau V, Roy B (2016) ELECTRE methods, international series in operations research & management science. In: Greco S, Ehrgott M, Figueira JR (eds) Multiple criteria decision analysis, 2nd edn, ch 0. Springer, pp. 155–185

Fiksenbaum L, Koyuncu M, Burke RJ (2010) Virtues, work experiences and psychological well‐being among managerial women in a Turkish bank. Equal Divers Incl Int J 29:199–212. https://doi.org/10.1108/02610151011024501

Giscombe K, Mattis MC (2002) Leveling the playing field for women of color in corporate management: is the business case enough? J Bus Ethics 37(1):103–119

Godoy L, Mladinic A (2009) Estereotipos y roles de género en la evaluación laboral y personal de hombres y mujeres en cargos de dirección. Psykhe 18(2):51–64