Abstract

Based on the samples from 260 enterprises in Jiangxi Province in 2022, this study examines the enterprises’ employment attitudes towards female employees from the perspective of HR managers. Through factor analysis, one-way analysis of variance, product-moment correlation analysis, and multiple regression analysis, this study investigates the female employment bias and its underlying mechanism across five dimensions: employee change, career development bias, policy impact, job competency and gender bias. The research findings confirm the employment bias against professional women by employers. The study reveals that the implementation of China’s three-child policy has exacerbated employment bias against female employees, especially in male-dominated enterprises. It is therefore recommended to provide more preferential policies for such enterprises. Furthermore, job competency has a significant negative correlation with gender employment bias. Continuing education and skills training are effective measures for professional women of childbearing age, particularly those in low-skilled jobs. With the further implementation of the three-child policy, this study anticipates a more challenging employment or promotion prospects for professional women. This study has also indirectly confirmed the employment dilemma of professional women of childbearing age, indicating potential obstacles in achieving the intended outcomes of the three-child policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gender employment bias often permeates subtly and affects women’s career development. According to the Guidelines for the Development of Chinese Women (2011–2020), women constituted 43.5% of China’s employment in 2020, nearly half of the total employed population. Enterprises have expectations on employees in terms of time and energy, necessitating women to navigate the delicate balance between their family roles as mothers and wives and their professional roles, particularly in dual-income households. Women have to struggle at family chores after finishing their office work, further compounded by China’s three-child policy and the deeply ingrained cultural belief among Chinese parents that “more children bring more blessings.” These factors contribute to professional women’s reluctance to expand their families.

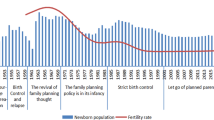

As marriage rates decline and individuals of childbearing age exhibit a decreased intention to have children, societal stakeholders are increasingly recognizing the pressing need to boost the fertility rate. In response to the challenges posed by an aging population and declining birth rates, the State Council issued the Decision on Optimizing the Birth Policy to Promote Long-Term and Balanced Development of Population on June 26, 2021, also known as the “universal three-child policy”, aimed at encouraging couples to have three children. This policy shift follows the release of data from the seventh national population census in May 2021, revealing a stark decline in China’s total fertility rate to 1.3 in 2020 and a reduced average annual population growth rate of 0.53%, compared to previous censuses figures (1.61% in 1964, 2.09% in 1982, 1.48% in 1990, 1.07% in 2000, and 0.57% in 2010). Notably, China’s marriage rate plummeted from 9.7‰ in 2011 to 5.4‰ in 2021, as reported in the 2021 Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Civil Affairs. Additionally, the average age at first marriage for both men and women has risen from 23.59 and 22.15 in 1990 to 29.38 and 27.95 years in 2020, respectively (Chen and Zhang, 2022). With the rollout and enforcement of China’s three-child policy, female employment has emerged as a new research hotspot. Existing research have focused on the following three aspects.

First, some research focuses on the improvement of female employment. How to juggle work and family life is a challenge that every professional woman of childbearing age will face. Especially in today’s China that advocates gender equality more than ever, the traditional model of “men are the breadwinner and women are the housewives” is under impact. As Song (2021) pointed out, science and technology promotes the socialization of housework, reduces women’s family burden, and therefore enables more women to integrate into society through work. Additionally, opening up to the outside world and international trade can also promote female employment, especially increasing the employment rate of low-skilled women (Chen et al., 2020). Furthermore, high-quality public services of pre-school education partly promote female employment as well (Xu, 2021). Shen (2021) pointed out that most urban women in China are employed in public management, education, health, culture, and other fields, while such concentration in market-oriented service industries such as retail and catering is not obvious. Chen and Zhou (2019) found that increasing female employment share has a positive impact on corporate profitability. The higher the female employment share, the higher the total factor productivity of enterprises (Li and Sheng, 2019).

Second, some research concerns about the difference treatment of women in employment. Women are disadvantaged in job opportunities, labor participation rate, wage level and career development (Chen et al., 2012). Gender bias exists in various organizations and fields (Vial et al., 2019). Women are disproportionately employed in low-skilled occupations (Darity and Mason, 1998) and are often asked personal questions about marriage and fertility during job interviews. For example, based on the data of Beijing, Hebei and Shandong provinces, Yang (2015) confirmed that 86.18% of female college students had encountered explicit or implicit gender discrimination in job hunting. Liu (2020) pointed out that men with similar education levels with women are engaged in more and better social work. Liu (2021) studied the gender bias at work and found that the career threshold for female fund managers is higher than that for the male, and the outstanding performance of female fund managers is related to gender bias. Gender bias is also reflected in the difference in women’s career ceiling. According to Evertsson and Duvander (2011), professional women who have taken a leave of 16 months or more are less likely to experience upward career change after returning to work, and overtime leave has a negative effect on their subsequent career change. Kmec and Skaggs (2014) pointed out that the lack of female managers in enterprises is a universal social problem. It is only possible to increase the proportion of female employees if the employer or manager is female (Vo and Ha, 2021).

Third, some research mainly investigates the reasons for the employment bias towards professional women. Zhao (2016) believed that the lack of gender concept in public policies leads to implicit discrimination against women in the employment market. In addition, Wang et al. (2017) pointed out that women face gender discrimination at every stage of their career. Wang et al. (2022) found that due to the spouse’s idealization of women’s behavior, professional women need to invest a lot of time and energy to meet high-standard family requirements and reduce work input. Zhang et al. (2019) pointed out that the benign gender bias of supervisors can also affect women’s career growth and development opportunities. Vial et al. (2018) suggested that women tend to be more supportive of other women in authority positions, whereas men respond more positively to other men than to women in authority positions. Women’s parental leave deepens the path of gender occupational segregation (Estévez-Abe, 2005). In addition, Wu and Zhang (2017) pointed out that gender bias at work is attributed to traditional gender impressions, occupational gender impressions, unbalanced distribution of industry gender, etc.

In summary, existing studies have analyzed the current employment status of women and the underlying causes of employment bias across various societal, familial, employer, and individual levels. They have also explored the occupational challenges faced by women, laying a solid foundation for further investigation. Within the context of the three-child policy, it is evident that some women are shifting from “non-professional” to “professional” and to “non-professional” roles. Women of childbearing age are faced with the dilemma of balancing childbearing and employment. The increase in the number of children will raise the probability of married women switching from employment to non-employment. Additionally, factors such as salary reductions, layoffs, and the educational needs of children during the COVID-19 pandemic have further exacerbated these challenges, potentially forcing women to leave their jobs and prioritize familial responsibilities. Existing studies predominantly explore the employment equality of women under the two-child policy and three-child policy from the perspectives of women, families and the society. They ignore the crucial role of employers and their employment bias towards women in the talent market. With the implementation of the three-child policy, it is necessary to investigate how employers perceive the childbearing decisions of professional women and their attitudes towards professional women with more than one child. Does the three-child policy increase the employment and career development difficulties of professional women? To answer these questions, a sample dataset comprising 260 enterprises in Jiangxi province was selected to explore the employment bias against professional women under the three-child policy and its consequential impact. The primary objective of this study is to gain insights into the employer’ psychology and attitudes, thereby providing valuable guidance for women navigating job searching and career progression.

Theoretical basis and research hypothesis

Lindblom’s theory of progressive decision making

Population policy is an important part of a country’s social and economic policy system. All countries strive to formulate a policy that conforms to their actual conditions and reflects their objective laws, so as to better boost economic and social development. Based on rational decision theory and bounded rational decision theory, Lindblom (1958) believes that a policy can be desirable rather than optimal since it is affected by a variety of factors. The introduction of a public policy is not the final decision of a problem, and progressive measures can be taken to modify and improve the existing policy to gradually realize the decision-making goal (Ding, 1999). Decision-makers can improve the relevant policies by trial and error and correction according to the problems revealed in the process of policy implementation. Like other social and economic policies, population policies are constantly adjusted, developed, changed and improved along with social development. They are relatively stable in the short term and subject to changes and adjustments in the long run. This feature is reflected in the evolution of China’s one-child policy, selective two-child policy, two-child policy and three-child policy.

Theory of time poverty

The theory of time poverty, originally introduced by Clair (1977), integrates time in the analysis of poverty, considering it as a crucial input. This theory underscores the equilibrium between work time, family time, and social time, highlighting gender as a significant factor affecting time allocation and perceptions of time poverty. The time poverty among professional women is far serious compared to men, compounded by enterprises’ considerations of labor costs and returns, placing women of childbearing age in disadvantageous career situations. First, women are more susceptible to time poverty than men. Conventional patterns of time distribution result in women facing a “double burden” of managing both household and work responsibilities, leading to constraints on their professional development and contributing to their time poverty (Qi and Xiao, 2018). Second, career interruptions stemming from childbirth and childcare diminish the stock of internal human capital within enterprises and escalate labor expenses. The employment of female staff may incur additional costs (Li and Feng, 2023), deepening gender-based occupational segregation and placing women at a disadvantage in terms of job opportunities, labor force participation rates, wage parity, and career progression. Third, having more children may exacerbate time poverty among professional women. Existing research has demonstrated a significant decline in female labor force participation rates and working hours during the 0–3 years following the birth of a first child (Yang and He, 2022). With the implementation of the three-child policy, women of childbearing age face the potential likelihood of bearing three children, further restricting their involvement in economic and professional activities and intensifying imbalances in time allocation. In conclusion, gender bias is the result of the combined effects of time poverty and gender labor. Traditional social expectations regarding family roles and the necessary time consumption for childcare render women more vulnerable to disadvantaged positions during job searches and career advancements in comparison to men.

Research hypothesis

Enterprise type and employment bias

Employers tend to hire men if men and women have the same productivity, until the difference in wages or productivity between women and men is large enough to offset the bias against women. Glick et al. (1997) pointed out that benign gender bias exists objectively. Because of the subjective consideration of protecting women, women are often limited to the traditional gender roles: “men are the breadwinner, and women are the housewives responsible for domestic chores”. In work, benevolent gender bias is mainly reflected in the positive attitude and caring behavior of leaders and colleagues towards women, which in essence limits women’s social roles and career development. In male-dominated industries, the public generally believes that women are not qualified for important positions, so women are often alienated. In female-dominated industries, however, preferential treatment is given to men in the name of fairness. Does employer bias and benign gender bias at work create career bias for working women? Do companies with different gender ratios have employment bias? Based on this, hypothesis H1 is proposed: female employees will suffer more employment bias in male-dominated enterprises.

Job competency and employment bias

According to the “economic man hypothesis”, in order to obtain more benefits, employers need to improve their industrial competitiveness and employees’ work efficiency. As a matter of fact, there are obvious differences between men and women in terms of productivity and labor participation rate, and men and women cannot completely replace each other. There are differences in the replacement rate of women to men in enterprises requiring different skills. There are also physical and mental differences between the two genders. For knowledge-based and skilled job with high job competence, women have a high degree of substitution for men. For physical, mechanizable, repetitive, low-skilled work, women have a low degree of substitution for men. Based on this, hypothesis H2 is proposed: job competency is negatively related to gender employment bias, that is, the lower the skill level requirement of the job, the more likely women are to experience more employment bias.

Enterprises’ understanding of three-child policy and employment bias

As “rational economic man”, employers often give priority to economic benefits when making employment decisions and require employees to maintain high work efficiency and produce high-quality work results. However, women giving birth can increase employment costs. For example, maternity leave can lead to career disruption and replacement, forcing employers to reduce the proportion or wages of female employees to shift costs (Olivetti and Petrongolo, 2017). With the introduction of the three-child policy and its supporting measures, women’s work will be done by other employees if their positions are retained during maternity leave. This will undoubtedly increase the work burden of the replacement staff, and then affect the interpersonal relationship in the enterprise, and hinder the normal operation of the enterprise. Working women with children face a relative disadvantage in terms of wages, benefits, time and effort, compared to women without children in the job search and promotion process. Therefore, hypothesis H3 is proposed: the implementation of the three-child policy will increase the employment bias against women, and HR’s understanding of the three-child policy will also increase its gender bias against female employees during employment.

Questionnaire description and variable processing

The sample data came from 260 enterprises in Jiangxi province. Human resource (HR) managers are professional personnel in enterprises specializing in human resource planning, employee recruitment and allocation, training and development, performance management, salary management, labor relations management, etc. They have full discourse power and can well reflect the real attitude of the management toward female employees. In order to effectively ensure the authenticity of the survey objects and reliability of data sources, one HR manager from each enterprise in Jiangxi HR Club was selected as a representative of the management for the questionnaire survey. Jiangxi HR Club is a professional club spontaneously organized by HR employees from various industries and enterprises in Jiangxi Province. Founded in 2016, it has always been committed to strengthening the communication and exchange between HR employees of various enterprises in Jiangxi Province, aiming to improve the human resource management level in Jiangxi. On the basis of relevant research, the abstract employment bias was decomposed into measurable indicators. Through expert interviews, group discussions and in-depth case interviews, a questionnaire with the specific information of HR manager and the enterprise was designed. In the pre-investigation stage, a total of 50 questionnaires were distributed, and SPSS 22.0 was used for item analysis and factor analysis of the pre-test questionnaire. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test statistic (KMO) is an index used to compare simple and partial correlation coefficients between variables, and its value ranges from 0 to 1. The closer the value is to 1, the more appropriate the relevant variable for factor analysis. The KMO test value was 0.859, >0.8. Moreover, Bartlett’s sphericity test was significant at the 0.01 level, and the common values extracted from each item were >0.2, which was suitable for factor analysis. Then, the exploratory principal component factor structure analysis was carried out on the pre-test questionnaire. Factor analysis results in Table 1 were obtained by excluding items with double loads and the items with loads <0.5. The factor structure of the questionnaire was reliable, and four factors were obtained, indicating that the construct validity of the questionnaire was good, and that the questionnaire had good internal consistency reliability. Finally, based on the item analysis and factor analysis, the final version of the survey questionnaire was revised.

The first part of the questionnaire is the basic demographic information of HR, including gender, age, working years, the gender distribution of employees, the form of enterprise ownership, the size of the employed enterprise, and the understanding degree of the three-child policy. A value of 1 is assigned for male and a value of 2 for female. The value 1 is assigned for ages 20 to 29 and 2 for ages 30 to 39, and 3 for ages over 40. A value of 1 is assigned for less than 5 years of working, 2 for 5–10 years of working, and 3 for over 10 years of working. If the enterprise employees are mostly males, the value is 1; if they are mostly females, the value is 2; if the two genders are roughly equal, the value is 3. The value of enterprise ownership is 1 for state-owned and collective enterprises, and 2 for private enterprises. Enterprises with 50 or fewer employees are given a value of 1, and those with 51–100 employees are given a value of 2, and those with 101 or more employees are given a value of 3. HR manager is assigned a value of 1 for a deep understanding of the three-child policy, 2 for a rough understanding, 3 for a slight understanding, and 4 for lack of understanding.

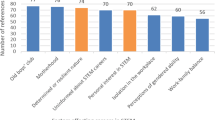

The second part of the questionnaire is composed of five dimensions: job competency, employment bias, employee change, career development bias and policy impact, with a total of 18 items. All items are scored by Likert scale, and the options are from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” and are scored 1–5 points. As shown in Table 1, the output table of the rotated component matrix, the 18 items are divided into four dimensions. Factor 1 is “female employment bias”, covering 5 items, namely “the number of women in key positions is relatively small in new employees”, “the number of men in new employees is much larger than that of women”, “the number of new female employees is significantly reduced”, “in the recruitment process, you prefer to choose men among the candidates of the same level”, and “the proportion of women in the management has fallen among new employees”. Factor 2 is “employee change”, covering 3 items: “after the implementation of the three-child policy, the relationship between male and female employees tends to be tense”, “after the implementation of the three-child policy, the profit generated by the employees has decreased significantly”, “after the implementation of the three-child policy, the work enthusiasm of the employees has decreased”. Factor 3 is “career development bias”, covering 5 items, namely “when promoting personnel, you will consider whether female candidates is willing to have children”, “female employees have more difficulty in promotion than male employees in the same position”, “compared with male employees, the salary and benefits of female employees have been reduced after the three-child policy”, “female employees have fewer training opportunities than male employees”, and “after the implementation of the three-child policy, female employees have a higher turnover rate than male employees”. Factor 4 is “policy impact”, covering 3 items: “the three-child policy affects your company’s HR strategy”, “the three-child policy affects the personnel adjustment of enterprises”, and “the three-child policy affects the employment of enterprises”. The fifth dimension is job competency. Each of the five dimensions is scored according to the sum of the subitems.

A total of 284 questionnaires were distributed in the formal investigation stage, of which 260 were valid, with an effective rate of 91.54%. As shown in Table 2, there were 53 males (20.38%) and 207 females (79.62%). According to the 2021 Human Resource Practitioner Survey Report, women are the majority of the HR group, accounting for 77.3%. The proportion of female HR managers in the sample was 79.60%, which was basically in line with the gender proportion of Chinese HR, showing the reliability of the sample data. In terms of age structure, 39 samples were 20–29 years old (accounting for 15%), 169 samples were 30–39 years old (accounting for 65%), and 52 samples were 40 years old and above (accounting for 20%). In terms of working years, 63 people (24.23%) have worked for <5 years, 87 people (33.46%) for 5–10 years, and 110 people (42.31%) for more than 10 years. In terms of gender distribution, 135 HR managers were employed by enterprises with more male workers (accounting for 51.92%); 61 by enterprises with more female workers (23.46%), and 64 (24.62%) by enterprises with an equal proportion of men and women. In terms of the form of enterprise ownership, 37 worked in state-owned enterprises, collective enterprises, and state-holding enterprises, accounting for 14.23%; 223 worked in private enterprises, foreign-invested enterprises, and enterprises invested by Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan, accounting for 85.77%. The sample HR managers worked in 14 industries including agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry and fishery, manufacturing industry, transportation industry, financial industry, and real estate industry. Among them, the number of HR managers working in the manufacturing industry, real estate industry, and construction industry are the largest, accounting for 16.92, 12.31 and 10.78%, respectively. In terms of enterprise scale, 32 enterprises with 50 employees or less, accounting for 12.31%, 45 with 51 to 100 employees, accounting for 17.31%, 183 with 101 or more employees, accounting for 70.38%. In terms of HR’s understanding of the three-child policy, 54 (20.77%) had a good understanding, 162 (62.31%) had a rough understanding, 42 (16.15%) had a slight understanding, and 2 (0.77%) had no understanding.

Empirical process and results

One-way ANOVA

One-way analysis of variance was conducted based on HR manager’s personal basic information, enterprise information and gender employment bias scores. The results are shown in Table 3:

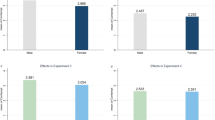

First, the gender of employees is an important factor affecting employment bias. In terms of HR manager’s gender bias scores, female-dominated enterprises scored significantly higher than male-dominated enterprises (P=0.000), confirming hypothesis H1: female employees may suffer severer employment bias in male-dominated enterprises.

Second, HR manager’s understanding of the three-child policy is one of the factors affecting employment bias. According to the employment gender bias scores, the score of those HR managers who did not know the three-child policy was significantly higher than that of their counterparts who known well about the three-child policy (P = 0.075). However, only two HR managers are not familiar. Whether their understanding of the three-child policy will affect the employment bias towards female employers needs to be further verified by subsequent studies.

In addition, the items of HR manager’s gender, age, working years, enterprise size, and enterprise ownership form failed the significance test. The research results in Table 3 also indicate that factors such as gender, age, working years, enterprise scale, and enterprise ownership form did not aggravate gender bias in employment.

Product-moment correlation and regression analysis

Before the regression analysis, the product-moment correlation analysis was carried out with job competency, employee change, career development bias, policy impact, and gender employment bias. As shown in Table 4, the Pearson correlation coefficients between the four variables of job competency, employee change, career development bias, and policy impact, and gender employment bias were all significant at the 99% confidence level. Among them, employee change, career development bias, and policy impact were positively correlated with gender employment bias, while job competency was negatively correlated with gender employment bias.With gender employment bias as the dependent variable, and post competency, employee change, career development bias, and policy impact after the implementation of the three-child policy as independent variables, a multiple regression model is constructed. In formula (1), Y is the gender employment bias, β0 is a constant term, β1, β2, β3, and β4 respectively are the partial regression coefficients of job competency, employee change, career development bias and policy impact after the implementation of the three-child policy, and e is the random error.

According to Table 5, the regression model is:

The F-value of multivariate linear model is 44.498, which corresponds to a significant p-value at the 95% confidence level, indicating that the equation is valid. All VIF values are less than 10 and tolerance values are greater than 0.1, so the equations do not have collinearity problems and are suitable for subsequent analysis. According to the coefficients in model (2), among the four variables of job competency, employee change, career development bias and policy impact, career development bias had the greatest impact on gender bias. In addition, employee change also had an obvious effect. These two findings are roughly consistent with the conclusions of relevant research, which will not be detailed herein. The next part will focus on the effects of job competency and policy impact.

Job competency is significantly negatively correlated with employment bias. With other conditions unchanged, the employment bias towards professional women will increase by 0.108 units as the job competency decreases by 1 unit. Therefore, hypothesis H2 is confirmed: the lower the requirement on job competency, the more likely female employees are to experience more employment bias.

The impact of the three-child policy is significantly positively correlated with gender bias in employment. With other factors unchanged, the employment bias towards female job seekers will increase by 0.265 units for every 1 unit increase in the policy impact caused by the implementation of the three-child policy. Therefore, hypothesis H3 is confirmed: the implementation of the three-child policy increases the gender employment bias, which is more obvious for women in less developed areas. The deeper the understanding of the three-child policy, the greater the gender bias of HR managers towards female workers in the hiring process.

Discussion and conclusions

Discussion

The elimination of gender-based employment bias and the promotion of gender equality in the workforce hold significant practical importance. Against the background of the three-child policy, the biases in employment practices within enterprises and the inherent challenges of child-raising exacerbate the disadvantaged position of professional women in the job market. It is imperative to establish a fair, just, secure, and supportive work environment for professional women to effectively balance their dual roles of wives and employees and receive equitable treatment in employment opportunities compared to their male counterparts. Therefore, this study attempts to explore the relationship between female employment bias and population fertility policies. From an HR perspective within organizations, this study investigates whether women of childbearing age will encounter heightened employment challenges, particularly in light of the policy emphasis on encouraging childbirth. Based on these insights, policy recommendations for enhancing the employment environment for women of childbearing age are proposed.

Existing research has demonstrated that women face greater obstacles in career development compared to men. Women often need to exert more effort than men under similar circumstances to access equal employment and advancement opportunities, which is consistent with established research findings (Olsen and LaGree, 2023; Yang et al., 2024). This underscores the pervasive presence of occupational bias as a manifestation of gender discrimination in contemporary society. Addressing occupational bias remains crucial for advancing gender equality and women’s empowerment. However, this study diverges from prior research by highlighting the negative spillover effects of the three-child policy on the employment prospects of women of childbearing age. These women face heightened employment discrimination, particularly pronounced in lower-skilled job roles. The potential for childbearing among women of childbearing age instills apprehension in enterprises when hiring female employees. Concerns regarding career interruptions due to childbirth and escalating welfare expenses lead companies to exhibit a preference for male employees or women who are currently not considering parenthood. The absence of supportive fertility policies further compounds enterprises’ reluctance to hire female workers, placing many women in a predicament where they feel hesitant to have children even if they desire children. Additionally, for female employees in low-skilled, homogenized job roles, the simplicity and substitutability of their tasks, as well as the low cost for enterprises to dismiss such employees, accentuate this bias in employment practices.

In conclusion, the deep-seated reasons for the exacerbation of employment bias against women of childbearing age due to fertility policies stem from enterprises’ concerns about the increased labor and welfare costs brought about by childbirth, as well as the imperfections of existing fertility policies and their complementary compensation policies. How to alleviate or eliminate employment discrimination caused by gender reasons, especially the employment discrimination arising from the three-child policy, is an important social issue that academic research and government should focus on in the future.

Conclusions

Based on a survey on 260 enterprises in Jiangxi province in 2022, this paper investigates the employer’s attitude toward female employees. This study confirms that the implementation of the three-child policy has increased the employer’s employment bias toward professional women. The results are particularly important for exploring the internal mechanism of female employment development, especially the employment bias towards professional women. The major conclusions are as follows:

First, the three-child policy has increased the employment bias against professional women within enterprises, particularly those with a predominantly male workforce. To address this issue, it is recommended to introduce more preferential policies to such enterprises. The demographic characteristics of HR, enterprise size, and the form of enterprise ownership are not the main causes of gender bias in employment. Gender discrimination exists across various types of enterprises, including male-dominated enterprises, gender-balanced, and female-dominated ones. However, gender discrimination is more serious in companies with a majority of male employees. One possible reason is that HR, as the enterprise’s representative, anticipates that the implementation of the three-child policy might indirectly raise costs associated with female employees, such as increased wages and benefits, along with disruptions during the maternity leave, potentially leading to a reduction in hiring female employees. In addition, in situations where when men and women compete for the same roles, enterprises tend to prioritize men to maximize profits, exacerbating the disadvantaged position of women in the job market. Despite possessing excellent skills and capabilities, including strategic career development plans, professional women face challenges due to occupational gender biases. They often need to invest more time and effort into their work to secure the same promotion opportunities as male counterparts, leaving them with limited time for family planning. To facilitate the effective implementation of the three-child policy, it is suggested that the government offer direct subsidies or tax incentives to enterprises based on their female employee count. Moreover, the government should provide subsidies to cover wages and allowances for female employees during maternity leave so as to reduce the financial burden on enterprises employing women.

Second, the employment bias against women of childbearing age is especially pronounced in low-skilled jobs characterized by high replaceability and strong similarity. Technology guidance such as continuing education and skills training is a good measure to enhance the employment prospects for women in this demographic. From the perspective of employers, this study confirms the widely accepted public belief in Chinese society that women of childbearing age will encounter employment bias. It also reveals that women in roles with low skill requirements experience more severe discrimination. Furthermore, at the social level, there are few outstanding female figures. During their career development phase, women often encounter interruptions due to childbearing, leading them to primarily engage in low-skilled jobs, consequently contributing to the marginalization of female employment structures. To sum up, the traditional social division of labor needs to keep pace with the times so as to actively promote the socialization of housework. Men should take the initiative to share the housework and free professional women from heavy family affairs so that women have the time and energy to receive career guidance, employment training, and continuing education. At the same time, governmental bodies should also provide preferential policies for women’s skill training, encouraging then to pursue further education and improve their labor skills. These efforts can help increase the proportion of female employees in the workforce.

Third, with the ongoing implementation of the three-child policy in China and a deeper understanding of its implications, the future employment or promotion path for professional women are anticipated to become more challenging. This study has indirectly confirmed the limited degree of policy implementation among women of marriageable age, hindering the intended impact of the three-child policy. As the enterprise faces uncertainties related to professional women taking maternity leave, the bias against unmarried professional women with no children may be more pronounced compared to married women with children. Similarly, biases against professional women with only one child could surpass those against women with more than one child. Consequently, the obstacles for professional women of childbearing age are increasingly evident, deterring them from pursuing motherhood due to the fears of encountering heightened employment biases. In addition to parenting pressure, workplace discrimination further compounds the challenges faced by professional women. Under the background of the three-child policy, the contradiction between child-bearing and professional responsibilities intensifies, magnifying the disadvantages of professional women in employment and placing them in an awkward situation. As a result, more women of childbearing age are not willing to have children. Many women have struggled to free themselves from traditional family chores and returned to work. Should they choose to have children, they are compelled to prioritize family obligations, inevitably impacting their professional pursuits. This predicament forces women into a dilemma, potentially forcing them to transition from employees to housewives. At the same time, professional women may encounter various employment biases upon returning to work post-childbirth. How to solve this dilemma, resolve the contradiction between enterprise development and female fertility, and help the three-child policy to achieve the expected effect is an urgent issue after the introduction of the three-child policy in China.

This study investigates the gender bias in the employment of professional women from the perspective of enterprises, utilizing data from 260 enterprises in Jiangxi Province. The research group aims to understand employers’ gender preference during employee selection, and offer insights specific to the local context regarding employment bias against professional women under the three-child policy. In the future, the research team plans to include HR managers as the research object at the national level to enhance the sample size and broaden the research area. Additionally, heterogeneity analysis will be conducted to delve deeper into variations across different regions and industries.

Data availability

The data involved in the study has been uploaded in the form of supplementary files, which can be obtained from the corresponding author if necessary.

References

Chen L, Xu XH, Deng XF (2020) International trade and the employment effect of Chinese women. Zhejiang Acad J 6:124–132. https://doi.org/10.16235/j.cnki.33-1005/c.2020.06.013

Chen M, Zhou S (2019) Female employment share and profits of manufacture firms: research on the impact and mechanisms. Bus Manag J 41(5):21–37. https://doi.org/10.19616/j.cnki.bmj.2019.05.002

Chen W, Zhang FF (2022) Marriage delay in China: trends and patterns. Popul Res 46(4):14–26

Chen ZX, Zhu LL, Chen Y (2012) The correlation between organizational sexism and women’s career development. Ind Eng Manag 3:135–140. https://doi.org/10.19495/j.cnki.1007-5429.2012.03.024

Clair V (1977) The time-poor: a new look at poverty. J Hum Resour 12(1):27–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/145597

Darity W, Mason P (1998) Evidence on discrimination in employment: codes of color codes of gender. J Econ Perspect 12(2):63–90. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.12.2.63

Ding H (1999) On Lindblom’s theory of incrementalist policy-making. Stud Int Tech & Econ (3):20–27

Estévez-Abe M (2005) Gender bias in skills and social policies: the varieties of capitalism perspective on sex segregation. Soc Politics: Int Stud Gend State Soc 12(2):180–215. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxi011

Evertsson M, Duvander AZ (2011) Parental leave-possibility or trap? Does family leave length effect swedish women’s labour market opportunities? Eur Sociol Rev 4:435–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcq018

Glick P, Diebold J, Balleywerner B et al. (1997) The two faces of adam: ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes toward women. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 23(12):1323–1334. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672972312009

Kmec JA, Skaggs SL (2014) The “state” of equal employment opportunity law and managerial gender diversity. Soc Probl 4:530–558. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2014.12319

Li HL, Feng JZ (2023) The impact of the number of children on the gender wage gap in china’s labor market: inter-temporal data analysis based on CGSS. J South China Norm Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 4:110–130+207

Li L, Sheng B (2019) Gender employment prejudice and firm productivity. China Econ Q 18(4):1267–1288. https://doi.org/10.13821/j.cnki.ceq.2019.03.05

Lindblom C (1958) Political analysis. Am Econ Rev 48(3):298–312

Liu AY (2020) Feminization of precarious employment and gender income gap: 1990-2015. J Peking Univ (Philos Soc Sci) 57(3):118–127

Liu YQ (2021) Why do female mutual fund managers perform better? gender bias and survivorship bias in financial industry. Bus Manag J 43(9):68–85. https://doi.org/10.19616/j.cnki.bmj.2021.09.005

Olivetti C, Petrongolo B (2017) The economic consequences of family policies: lessons from a century of legislation in high-income countries. J Econ Perspect 31(1):205–230. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.1.205

Olsen K, LaGree D (2023) Taking action in the first five years to increase career equality: the impact of professional relationships on young women’s advancement. Gend Manag 38(7):925–941. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-02-2022-0058

Qi LS, Xiao YD (2018) Gender, low-paid status, and time poverty in urban China. Fem Econ 24(2):171–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2017.1404621

Shen MY (2021) Research on the employment structure and driving factors of urban female employees in ganzi and aba prefecture in sichuan: analysis on the data of the fourth national economic census in sichuan province. Tibet Stud 1:85–94. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-0003.2021.01.011

Song YP (2021) Opportunities and challenges for women’s employment in digital economy. People’s Trib 30:82–85

Vo TT, Ha TT (2021) Decomposition of gender bias in enterprise employment: Insights from Vietnam. Econ Anal Policy 70:182–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2021.02.007

Vial AC, Brescoll VL, Dovidio JF (2019) Third-party prejudice accommodation increases gender discrimination. J Personal Soc Psychol 117(1):73–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000164

Vial AC, Brescoll VL, Napier JL et al. (2018) Differential support for female supervisors among men and women. J Appl Psychol 103(2):215–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000258

Wang HZ, Mei XF, Wei XH (2017) How do female employees conduct gender identity-based impression management. Adv Psychol Sci. 25(9):1597–1606. https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.j.1042.2017.01597

Wang XC, Li LX, Xu NZ et al. (2022) The influence of spouses’ benevolent sexism on professional women’s thriving at work: a moderated mediation modelc. J Psychol Sci. 45(1):118–125. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20220117

Wu HW, Zhang WJ (2017) An analysis of workplace gender bias based on the integration model of misfit mechanism. Commer Res 9:135–143. https://doi.org/10.13902/j.cnki.syyj.2017.09.019

Xu X (2021) The impact of public investment in preschool education on female employment—an empirical analysis based on provincial data. Fisc. Sci. 9:99–109. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-2563.2015.04.010

Yang F, He YC (2022) Motherhood penalty on chinese women in labor marker. Popul Res 46(5):63–77

Yang H (2015) Social impacts of gender-based discrimination in employment among female university students. Collect Women’s Stud 4:97–103. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-2563.2015.04.010

Yang T, Kacperczyk A, Naldi L (2024) The motherhood wage penalty and female entrepreneurship. Organ Sci 35(1):27–51. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2023.1657

Zhang SS, Xie JY, Wu M (2019) Sweet poison: how does benevolent sexism affect women’s career development? Adv Psychol Sci 27(8):1478–1488. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2019.01478

Zhao MH (2016) Gender equity should be promoted by public policies under the two-child policy. Popul Res 40(6):38–48

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks go to Jiangxi Provincial Educational Science Planning Project (23QN001), Jiangxi Provincial Degree and Postgraduate Education Reform Project (JXYJG-2022-013), and Nanchang University Communist Youth League Theory Research Project (NCUGQT202303) for the generous funding support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qun Gao had the original idea and collected data for this study. Mei Zhao and Hengyang Chen provided suggestions and comments. Then Qun Gao and Hengyang Chen drafted the manuscript and approved the final one. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the university. The research project was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Public Policy and Management of Nanchang University on 15 March 2022 (Code: NCUG2022008).

Informed consent

During the investigation, the study has signed informed consent from all participants included in the study. The information provided in the consent form explained the study’s objective, the voluntary nature of participation, the possibility to withdraw from the study at any time, the procedure to collect the data, the materials and measures to be used, and the anonymity and privacy statement.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Q., Zhao, M. & Chen, H. Effects of the three-child policy on the employment bias against professional women: evidence from 260 enterprises in Jiangxi province. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 544 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03063-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03063-9