Abstract

Empowering teachers through sharing communal decision-making responsibility via distributed leadership has been shown to be effective for positive change in schools. While studies have proposed various psychosocial channels through which positive effects on teacher wellbeing can be realized, there is scarce evidence on how this relationship is influenced by teacher self-efficacy. This study examines how self-efficacy mediates the relationship between distributed leadership, job and career wellbeing among secondary school teachers, employing a partial least-squares structural equation model using the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) Shanghai dataset (N = 3799). Results show that distributed leadership is positively associated with improvement in self-efficacy (std. β = 0.33, P < 0.001), job wellbeing (std. β = 0.51, P < 0.001), and career wellbeing (std. β = 0.45, P < 0.001), whereas self-efficacy is positively correlated with job wellbeing (std. β = 0.15, P < 0.001), but not career wellbeing (std. β = −0.01, P = 0.69). In terms of mediation effects, self-efficacy positively mediates the relationship between distributed leadership and job wellbeing (std. β = 0.05, P < 0.001), but distributed leadership does not indirectly influence career wellbeing (std. β = −0.002, P = 0.70) via channels through self-efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Against the backdrop of increasing globalization and desegregation of sectoral jobs (Gao et al., 2021), studies have shown that effective workplace management practices play critical roles in affecting work communities (Marchese et al., 2019). Distributed leadership, which is characterized by proactive multidimensional interaction among community members in work-settings, has been regarded as a promising organizational practice in promoting workplace engagement (Gunzel-Jensen et al., 2018). For one, distributed leadership emphasizes joint involvement, participation, and decision-making in the workplace, and envisions the empowerment of community members as conducive to stimulating employee self-efficacy and productive work behavior (Xu et al., 2021). For another, distributed leadership requires community members to develop the necessary empathy to better understand each other by exchanging roles according to the characteristics and necessity of community-related tasks at different stages and for different operational purposes (Bolden, 2011).

Schools, as one of the most common forms of work communities, have traditionally operated under hierarchical structure (Han et al., 2016). Nonetheless, many education systems are facing a common challenge to staff schools with talented, energetic, and effective teachers in recent years. While teachers are considered deterministic in ensuring students’ academic success, many are reportedly suffering from sustained work stress and are at the brink of job burnout (Bhai and Horoi, 2019). For instance, teaching has been ranked as one of the most stressful professions in many countries (Saloviita and Pakarinen, 2021). Common explanations for pre-retirement teacher attrition have been attributed to unattractive compensation, unfavorable work conditions, and low job satisfaction as leading factors (Liu, 2021). In order to attract and retain quality teachers in the classroom and provide high-quality instruction, teacher well-being has attracted considerable attention. To that end, one promising approach without creating a substantial fiscal burden, is understanding how teachers’ job and career needs can be better satisfied in their work communities.

Prior studies have identified distributed leadership as an effective measure in addressing the match between teacher needs and school resource allocation (Ingersoll and May, 2012). In detail, evidence has shown that distributed leadership positively affects teachers’ self-efficacy (Liu and Werblow, 2019), which consequently improves work attitude (Hulpia et al., 2012) and work enthusiasm (Karabiyik and Korumaz, 2014). Self-efficacy, often regarded as a key productivity trait, has been shown to not only boost employee satisfaction but also enhance community cohesiveness and sustaining community growth (Fang et al., 2019). Notwithstanding, while studies have examined the link between distributed leadership and teacher well-being in schools, little is known regarding the extent to which this relationship is shaped by varying degrees of teacher self-efficacy. To address this gap in the literature, this study utilizes the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) Shanghai dataset and examines how self-efficacy mediates the relationship between distributed leadership in schools and teacher well-being on the job. In this regard, the focal case in this current study, secondary school teachers, offers a unique glimpse at how these factors intricately interlink, especially since there has been a significant policy shift in recent years to encourage teacher empowerment through less-hierarchical managerial styles.

Theoretical framework

Distributed leadership as key determinant of teacher wellbeing

Both literature in educational and social psychology inform the present inquiry, in that studies focusing on group and polyarchy theory have shown that distributed leadership, which is the emphasis on empowering individual actors in contributing towards organizational growth, holds significant aggregate returns (Liu and Du, 2022). In school settings, distributed leadership refers to fluid and effective interaction between school administrators and teaching staff, considering the joint involvement of multiple participants in a hierarchy-neutral manner (Torres, 2018). For many schools, implementing distributed leadership translates into allocating various communal leadership responsibilities to teachers, as a way to mobilize and motivate teachers in participating in school affairs (Hester et al., 2009). Conceptually, the redistribution of leadership responsibilities can strengthen teachers’ recognition of schools (Hulpia and Devos, 2010), and in turn, also tend to narrow the power distance between community members, thus bringing about positive organizational change in school managerial styles (Zheng et al., 2019). Studies have indicated that implementing distributed leadership in schools is not only conducive to improving teacher performance (Harris, 2013), school development (Al-Harthi and Al-Mahdy, 2017), and student achievement (Malloy and Leithwood, 2017) but also significantly predicts teacher wellbeing (Johnson et al., 2012).

To this end, evidence has shown that teacher wellbeing, which is regarded as a critical factor determining career attraction and job turnover among teachers, can be operationally categorized as consisting of bi-dimensional characteristics: job wellbeing and career wellbeing (Acton and Glasgow, 2015). On the one hand, job wellbeing refers to teachers’ emotional experience and reception of their work conditions, instructional tasks, and supervisors’ managerial styles, which can either independently or jointly affect their assessment of self-actualization and valuation of on-the-job satisfaction (Ingersoll et al., 2018). Teachers’ job wellbeing has been found to strongly predict instructional performance and within-sector job mobility, especially in educationally adverse settings involving disadvantaged or marginalized children (Toropova et al., 2020). On the other hand, career wellbeing is the degree to which a teacher’s career experience is consistent with career expectations, including the progressive self-realization that is constantly evaluated internally and externally (İnandı et al., 2022). Existing research has shown that career wellbeing not only affects teachers’ motivation and engagement on-the-job, but also serves as a risk factor in predicting pre-retirement attrition. (Sutcher et al., 2016). Consequently, there have been both academic and policy interests in seeking ways to improve teacher wellbeing, while acknowledging the multidimensionality and complex nature of teaching (McInerney et al., 2018).

More concretely, research on distributed leadership has linked teacher wellbeing to development of a school managerial climate that expands teacher agency and encourages participation in collective school decision-making (Devos et al., 2014). For one, empowering teachers with increased work autonomy is a key step in motivating and retaining teachers in teaching (Torres, 2019), and is particularly useful in helping students achieve learning gains to compensate for disadvantages associated with adverse family or environmental factors (Chetty et al., 2014). For another, incentivizing teachers to take on school leadership responsibilities creates a sense of school ownership (Simon and Johnson, 2015), which bolsters the intrinsic development of professional communities and inter-level collaborations (Thomas and Feldman, 2014). In particular, research has found that teachers who pay more attention to teaching, engage in joint teaching, and professional discussion have higher school commitment, and tend to exhibit higher levels of job and career wellbeing (Ballantyne and Zhukov, 2017).

Teacher self-efficacy as mediating link

In classical social cognitive theory, Bandura (1977) defined self-efficacy as a form of belief in one’s capabilities to organize and excuse the course of action required to produce given attainment. In the education realm, prior research has indicated that higher levels of teacher self-efficacy have significant influence on both instructional practice (Kavanoz et al., 2015) as well as on student learning outcomes (Zee and Koomen, 2016). More concretely, teacher self-efficacy is commonly conceptualized as a measure of self-perception, which determines teachers’ own beliefs about the sustainability of their efforts in planning, organizing, and implementing instructional activities (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2010). There is a growing body of literature highlighting the central weight that self-efficacy holds in shaping how teachers perceive the nature of their work, as well as the ways in which they respond to challenges and obstacles that arise in routine instruction and work (Klassen and Chiu, 2010). For instance, studies have examined how self-efficacy is positively linked with instructional effectiveness (Li et al., 2019) since teachers with a higher sense of self-efficacy are more likely to implement organizational planning and exhibit a higher willingness to adopt new teaching methods to meet students’ learning needs (Vieluf et al., 2013). From a psychological perspective, teacher self-efficacy defuses and relieves work-related acute stressors (Lauermann and Johannes, 2016), and is likely to activate intrinsic motivation to realize individual and communal goals (Flores et al., 2020).

In school settings, teacher-led leadership modalities have been introduced extensively in a variety of educational contexts, where teachers are encouraged to have sufficient and flexible time to conduct targeted teaching to their students according to their own judgment (Al-Yaseen and Al-Musaileem, 2015). In this regard, an emerging body of research shows that distributed leadership can improve teacher self-efficacy through three key channels. First, empowering teachers through enacting distributed leadership practices tends to create a positive communal work climate, in which teachers feel comfortable sharing knowledge and are more likely to work collaboratively to improve instruction (Liu et al., 2021). Second, when teachers gain greater control over their work environment, they are more likely to take ownership of work assignments, and consequently invest more in the preparation, implementation, and reflection of teaching (Duyar et al., 2013). Thirdly, verbal persuasion and support from leaders can be an important incentive to cultivate a sense of self-efficacy among teachers, who long for a platform that promotes communication between administrators and teachers in achieving common objectives (Zheng et al., 2019).

More important, studies have shown that self-efficacy is positively associated with a range of job and career outcomes, including reducing premature exits from work communities (Granziera and Perera, 2019). For instance, teachers with higher levels of self-belief and emotional engagement show more positive perceptions about their work and are more likely to respond favorably when asked to assess their contributions at work (Perera et al., 2018). This association is also shown to be bi-directional, such that those teachers with better instructional performance are more likely to indicate a higher sense of appreciation, confidence, and satisfaction with their work (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2014). Some evidence suggests that this increased level of appreciation, confidence, and satisfaction can positively influence instructional competency in dealing with student conflicts, lesson planning, and maintaining work relationships (Wang et al., 2015). Notwithstanding, while the important role of teacher self-efficacy in linking distributed leadership and teacher wellbeing has been widely documented, few studies have attempted to examine these three factors in conjunction, nor have studies attempted to explore the degree of influence that teacher self-efficacy has on the relationship between distributed leadership and teacher wellbeing, prompting the present study.

Method

The current study

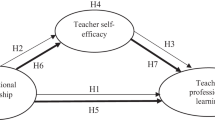

Given the importance of distributed leadership for improving teacher wellbeing, the current study aims to fill the literature gap in understanding the role of teacher self-efficacy in mediating the link between distributed leadership on job wellbeing and career wellbeing, by estimating a partial least-squares structural equation model (PLS-SEM) using the TALIS-Shanghai dataset. A structural equation model is built to test hypotheses on the potential mechanisms between distributed leadership, teacher self-efficacy, job wellbeing and career wellbeing, as it appears in Fig. 1. In more detail, the following research questions are pursued:

Hypothesis 1: Distributed leadership can directly and positively affect teacher self-efficacy, job and career wellbeing.

Hypothesis 2: Distributed leadership can indirectly and positively affect both job and career wellbeing, via teacher self-efficacy.

Data and sample

This study leverages the publicly-available Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), which was conducted and collected by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2018. TALIS is the first international series of cross-sectional surveys focusing on the learning environment and working conditions of secondary-school teachers (Ainley and Carstens, 2018). Prior to the main study, a pilot field trial was conducted in March 2016 to ensure instrument validity, translation quality, and operational logistics. Field trial data were analyzed to assess construct validity and items were modified accordingly, based on scale reliability cutoffs α ≥ 0.700 and φ ≥ 0.700. For the main TALIS study, a stratified two-stage probability sampling design was adopted such that the main survey consisted of approximately 200 schools per country and 20 teachers within each school. The teacher questionnaire intended to collect information on all aspects of teaching, including teacher preparation, work condition, professional development, and teacher well-being.

The TALIS dataset is unique and fits the purpose of this study because it contains teacher responses to questions on the extent of specific managerial practices in schools, their levels of self-efficacy, as well as the degree of satisfaction with jobs and careers. More uniquely, the TALIS dataset allows for a combination of sets of questions that juxtapose factual information, reports of implemented activities, and attitudes towards these activities, which can be analyzed in conjunction to present a deeper level of understanding of what exists or is lacking, or what is implemented, how it works, and how its impact is perceived at the teacher-level (OECD, 2018).

For the current study, we elect to focus on the TALIS-Shanghai dataset, which surveyed 3976 teachers in Shanghai, which is a large urban metropolitan on the east coast of China. Operationally, 177 observations (0.04%) were omitted from the empirical analysis due to pair-wise missing responses, and the final research subject count was 3799. Before empirically testing the hypotheses, we present the demographic background information of all 3799 included subjects, shown in Table 1. Among the subjects, 2811 are female (73.99%) and 988 are male (26.01%); 3269 (86.05%) subjects report holding a bachelor’s degree or below, and 530 (13.95%) subjects report holding a master’s degree or above; a range of teaching experience at current school ranged from 0 to 39 years, with an average of 11.92 years, and range of teaching experience in total ranged from 0 to 49 years, with an average of 16.65 years.

Measures

Distributed leadership

Distributed leadership is the key independent variable in this study. It is conceptualized as a latent construct that is measured by an eight-item scale in the TALIS 2018 teacher questionnaire. Items asked teachers: (1) whether the school provides opportunities for “staff”, “parents or guardians”, and “students” opportunities to actively participate in school decisions; (2) whether the school has a culture of shared responsibility for school issues; (3) whether the school culture characterized is mutual support; (4) whether the school staff shares a common set of beliefs about teaching and learning, and enforce rules for student behavior consistently throughout the school; (5) whether the school encourages staff to lead new initiatives. All responses were recorded on a four-point Likert scale, from which subjects could select “(1) strongly disagree”, “(2) disagree”, “(3) agree”, or “(4) strongly agree”.

In contrast to most existing studies, this study focuses on the teacher-perceived aspects of distributed leadership, as defined as measures reported by teachers, so as to avoid traditional measurements that exclusively relied on school administrator responses. For measurement verification, we report construct validity indices for distributed leadership in Table 2, where Cronbach’s alpha is recorded as 0.952 and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy test result is recorded as 0.931, both indicating good construct validity. Standardized factor loading results of the eight items are also presented in Table 2, which range from 0.80 to 0.90, indicating that this latent construct is empirically valid. Information on the variance inflation factor (VIF) is itemized in the final column of Table 2, which fluctuates between 2.74 and 4.44, and the mean VIF is evaluated at 3.94 and below the VIF threshold of 5, suggesting little multicollinearity concern (Hair et al., 2019).

Teacher self-efficacy

Teacher self-efficacy is the mediator variable in this study. For Teacher self-efficacy measurements, we conceptualize it as a latent variable and measured it using a 13-item scale in the TAILS (2018) teacher questionnaire. The scale includes four dimensions: (1) teacher self-efficacy in student engagement, (2) teacher self-efficacy in instruction managements, (3) teacher self-efficacy in classroom management, and (4) teacher self-efficacy in using technology for educational purposes. All responses were recorded on a four-point Likert scale, from which subjects could indicate “(1) not at all”, “(2) to some extent”, “(2) quite a bit”, or “(4) a lot”.

We report construct validity indices for teacher self-efficacy in Table 3, where Cronbach’s alpha is recorded as 0.952 and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy test result is recorded as 0.956, both indicating good construct validity. Standardized factor loadings for each item are also presented in Table 3, which range from 0.80 to 0.89, indicating that this latent construct is empirically valid. Information on the variance inflation factor (VIF) is itemized in the final column of Table 3, which fluctuates between 1.50 and 4.60, and the mean VIF is evaluated at 3.14 and below the VIF threshold of 5, suggesting little multicollinearity concern (Hair et al., 2019).

Teacher wellbeing

Teacher wellbeing is the dependent variable in this study. In consultation with the existing literature (see Acton and Glasgow, 2015), we conceptualize teacher wellbeing as consisting of two key domains and operationalized them as latent constructs: job wellbeing and career wellbeing. For job wellbeing measurements, we rely on a five-item scale in the TAILS (2018) teacher questionnaire. For career wellbeing measurements, we utilize eight-item scale in the TAILS (2018) teacher questionnaire. All responses were recorded on a four-point Likert scale, on which subjects indicated “(1) strongly disagree”, “(2) disagree”, “(3) agree”, or “(4) strongly agree”.

We report construct validity indices for both job and career wellbeing in Panels A and B of Table 4, where Cronbach’s alpha is recorded as 0.867 and 0.840, respectively; the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy test results are recorded as 0.844 and 0.822 for the two latent variables, which indicates an acceptable level of construct validity. Additionally, standardized factor loadings of the five items measuring job satisfaction ranged from 0.71 to 0.94, while the standardized factor loadings of the eight items measuring career wellbeing ranged from 0.61 to 0.89, indicating that both scales exhibit good validity. Information on the variance inflation factor (VIF) is itemized in the final column of Table 4, which fluctuates between 1.83 and 3.13 for job wellbeing and between 1.40 and 2.42 for career wellbeing, and the mean VIF is evaluated at 2.42 and below the VIF threshold of 5, which rules out concerns for multicollinearity issues (Hair et al., 2019).

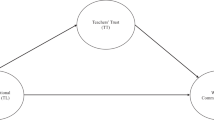

Data analysis

In this study, all statistical analyses are performed using STATA version 15.1 (Stata, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) software. We build a structural equation model (SEM) to examine the relationship between distributed leadership, job wellbeing and career wellbeing, and fit a mediation model to evaluate the extent to which teacher self-efficacy act as a mediator in this relationship (see Fig. 2). Methodologically speaking, SEM allows the researcher to statistically examine the extent to which proposed hypotheses are supported by empirical data to reflect theoretical predictions, and this present study utilizes partial least squares SEM model with the dual goal of minimizing the error term and maximizing explanatory power. In practice, utilizing the SEM approach has several noteworthy improvements over traditional regression-based analytic approaches. For one, this study is able to substantially reduce measurement error for the key outcome and predictor variables, by conceptualizing them as independent latent constructs. For another, this study simultaneously models both direct and indirect pathways and reduces type-I error rates as a result of multiple pathways being estimated and tested jointly. In conducting these tests, we report goodness-of-fit statistics and assess mediation effects by three independent statistical tests including Delta, Sobel, and Monte Carlo, with 5000 bootstraps. To further address potentially remaining multicollinearity concerns, both dependent and independent variables are centered and standardized to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, in order to reduce issues with structural multicollinearity (Imai, Keele, and Tingley, 2010).

Results

First and foremost, the structural equation model indicates a reasonably good fit, with model fit measures \(\chi _{522}^2\) = 13,724.325(P < 0.001), CFI (Comparative Fit Index)=0.867, TLI (Tucker–Lewis Index)=0.857, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)=0.051, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR)=0.082. Generally speaking, bound for CFI and TLI indicating good model fit is 0.90, while for RMSEA and SRMR, their limits are 0.06 and 0.08, respectively (see Hu and Bentler, 1999). Therefore, we conclude that our model is valid and satisfies these requirements.

Second, we evaluate both direct and indirect effects of the structural mediation model utilizing results presented in Table 5, for which all effects are reported as standardized coefficients (std. β). For direct effects, each standard deviation increase in distributed leadership is positively associated with improvement in teacher self-efficacy (std. β = 0.33, P < 0.001), job wellbeing (std. β = 0.51, P < 0.001), and career wellbeing (std. β = 0.45, P = < 0.001). These findings are consistent with Hypothesis 1 and empirically confirm it. To add, teacher self-efficacy is positively correlated with job wellbeing (std. β = 0.15, P < 0.001), but not career wellbeing (std. β = −0.01, P = 0.69). For indirect effects, teacher self-efficacy significantly mediates the positive link between distributed leadership and job wellbeing (std. β = 0.05, P < 0.001), but not career wellbeing (std. β = −0.002, P = 0.70).

Third, when assessing these results in conjunction, it can be inferred that the indirect effect of distributed leadership on job wellbeing operating through teacher self-efficacy, is estimated to be approximately 10% of its direct effect (0.05/0.51). Considering that distributed leadership has both a direct and indirect channel influencing job wellbeing, its total influence on job wellbeing is approximately 0.56 (P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.55–0.57), of which 9% of this total effect (0.05/0.56) is indirectly channeled through teacher self-efficacy. These findings are partially consistent with Hypothesis 2 and empirically show that distributed leadership can indirectly and positively affect job wellbeing via teacher self-efficacy, but not career wellbeing.

Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this study is to fill the literature gap in understanding the role of teacher self-efficacy in mediating links between distributed leadership on teacher job wellbeing and career wellbeing. Although teacher self-efficacy has been identified as a critical factor in relating distributed leadership and teacher wellbeing, few studies have attempted to investigate their inter-linked relationship in conjunction. In light of these needs, we empirically examined the mediating role of teacher self-efficacy by fitting a structural mediation model using TALIS-Shanghai dataset consisting of 3799 secondary school teachers. Findings from the structural mediation model are consistent with prior studies that show distributed leadership is positively associated with teacher self-efficacy, job wellbeing, and career wellbeing, and also uncover new evidence that teacher self-efficacy positively mediates the link between distributed leadership and job wellbeing, but not for career wellbeing. In other words, findings suggest that while distributed leadership is beneficial for enhancing teacher self-efficacy, job wellbeing, and career wellbeing, its mediated link via teacher self-efficacy is more complex.

At the operational-level, attracting high-quality teachers and preventing their exit from school communities is regarded as a long-term challenge to educational development worldwide (Liu and Steiner-Khamsi, 2020). Studies have shown that a combination of pecuniary and non-pecuniary factors is reshaping teachers’ occupational decisions and mark critical shifts in what teachers expect from their jobs (Liu and Xie, 2021). On the one hand, scholars tend to agree that teachers appreciate the feeling that their voice, opinion, and participation in school decision-making are valued (García Torres, 2018). Particularly, teachers in those schools demonstrating higher degrees of distributed leadership tend to report a stronger sense of school loyalty and report being more willing to collaborate in tackling work-task challenges (Liu and Du, 2022). One possible explanation could be that teachers, as well as any professional, appreciate their voices being valued in the workplace. On the other hand, doing away with hierarchical management in school communities can motivate teachers in contributing professional knowledge towards school governance (Zheng et al., 2019). Without efficient mechanisms for collecting and processing accurate information in highly contextualized work scenarios, decision mismatch in school governance becomes highly likely and is reasonably expected to influence school managerial performance, teacher instructional effectiveness, and student learning (Liu, 2021). It is highly probable that exercising distributed leadership in work-setting communities can lead to improvements in employee–job matching, which boosts on-the-job productivity. In this regard, recent studies have highlighted the empowerment effects of recognizing and respecting teachers’ professional opinions (DeMarco, 2018).

It is worth noting two important study limitations. First, this study is based on the cross-sectional survey, which limits the extent to which causality of the PLS-SEM models could be made. Second, the TALIS-Shanghai dataset is restricted to urban teachers who teach in lower-secondary schools (ISCED 2), which requires caution in generalizing results to the broader teacher population in China. Notwithstanding, our findings are novel in that a strong positive relationship between teacher self-efficacy and job wellbeing is identified, but self-efficacy is not statistically linked with career wellbeing. In prior research, job and career wellbeing are often treated as a unitary construct (Edinger and Edinger, 2018), however, career wellbeing has been shown in many instances to be more complex and closely related to extrinsic factors, such as wages, career progression, societal valuation, etc. (Ballantyne and Retell, 2020). In this study, we show that teacher self-efficacy has a significant mediating effect between distributed leadership and job wellbeing, but not on career wellbeing, which has been shown in prior studies to be influenced primarily by work bonuses, promotion, and professional opportunities (Bostjancic and Petrovcic, 2019). Therefore, while it is critical to acknowledge the usefulness of distributed leadership for improving self-efficacy and subsequently career wellbeing, it is also important to realize its limits (Sun and Xia, 2018). Put more simply, self-efficacy alone is not enough to substantially alter the adverse psychosocial valuation of their work communities among teachers (Liu and Onwuegbuzie, 2012), and scholars have advocated for more tangible factors such as career support, development opportunities, and salary bonuses to improve teacher retention (Liu, 2021).

To date, few studies have identified the psychosocial saliency of teacher self-efficacy in mediating the positive influence of distributed leadership on teacher wellbeing in the context of secondary schools in Shanghai, China. Synthesizing the above findings, this current study proposes a new theoretical framework for understanding the work community psychology mechanisms through which emerging management practices can influence teacher self-efficacy and consequently teacher wellbeing. Particularly, when teachers feel under-appreciated and mentally alienated from their work, they are more likely to consider alternative job and career options that offer higher levels of appreciation and satisfaction. When teachers do leave their posts, it is particularly challenging for underserved, underfunded, and marginalized communities to re-staff, and the associated loss of teaching experience and institutional knowledge is extremely detrimental for these communities. Last but not least, our findings highlight the importance of community plurality in work-settings by involving, empowering, and giving teachers voice in school operational procedures. Relatedly, our findings are also relevant for predicting the less visible consequences for the standardization and bureaucratic management of the instruction movement (see Peurach et al., 2019) and how school managerial practices and processes shape or re-shape teacher wellbeing (see Shen et al., 2012).

Data availability

Data used in this study can be publicly accessed from the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) data repository (https://www.oecd.org/education/talis/talis-2018-data.htm), with permission of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

References

Al-Harthi ASA, Al-Mahdy YFH (2017) Distributed leadership and school effectiveness in Egypt and Oman: an exploratory study. Int J Educ Manag 31(6):801–813. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-05-2016-0132

Acton R, Glasgow P (2015) Teacher wellbeing in neoliberal contexts: a review of the literature. Aust J Teacher Educ 40(8). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n8.6

Ainley J, Carstens R (2018) Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018 conceptual framework. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 187. OECD Publishing, Paris

Al-Yaseen WS, Al-Musaileem MY (2015) Teacher empowerment as an important component of job satisfaction: a comparative study of teachers’ perspectives in Al-Farwaniya District, Kuwait. Compare 45(6):863–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.855006

Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 84(2):191–215

Bhai M, Horoi I (2019) Teacher characteristics and academic achievement. Appl Econ 51(44):4781–4799. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1597963

Bostjancic E, Petrovcic A (2019) Exploring the relationship between job satisfaction, work engagement and career satisfaction: the study from public university. Hum Syst Manag 38(4):411–422. https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-190580

Ballantyne J, Retell J (2020) Teaching careers: exploring links between well-being, burnout, self-efficacy and Praxis Shock. Front Psychol 10:2255. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02255

Ballantyne J, Zhukov K (2017) A good news story: early-career music teachers’ accounts of their “flourishing” professional identities. Teach Teach Educ 68:241–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.009

Bolden R (2011) Distributed leadership in organizations: a review of theory and research. Int J Manag Rev 13:251–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00306.x

Chetty R, Friedman J, Rockoff J (2014) Measuring the impacts of teachers II: teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood. Am Econ Rev 104(9):2633–2679. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.9.2633

Devos G, Tuytens M, Hulpia H (2014) Teachers’ organizational commitment: examining the mediating effects of distributed leadership. Am J Educ 120(2):205–23. https://doi.org/10.1086/674370

Duyar I, Gumus S, Sukru Bellibas M (2013) Multilevel analysis of teacher work attitudes: the influence of principal leadership and teacher collaboration. Int J Educ Manag 27(7):700–719. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijem-09-2012-0107

DeMarco AL (2018) The relationship between distributive leadership, school culture, and teacher self-efficacy at the middle school level. Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses, (ETDs). https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2594

Edinger SK, Edinger MJ (2018) Improving teacher job satisfaction: the roles of social capital, teacher efficacy, and support. J Psychol 152(8):573–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2018.1489364

Flores G, Fowler DJ, Posthuma RA (2020) Educational leadership, leader-member exchange and teacher self-efficacy. J Global Educ Res 4(2):140–153. https://doi.org/10.5038/2577-509X.4.2.1040

Fang Y-C, Chen J-Y, Wang M-J, Chen C-Y (2019) The impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behaviors: the mediation of psychological capital. Front Psychol 10:1803. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01803

Granziera H, Perera HN (2019) Relations among teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, engagement, and work satisfaction: a social cognitive view. Educ Psychol 58:75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.02.003

García Torres D (2018) Distributed leadership and teacher job satisfaction in Singapore. J Educ Adm 56(1):127–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-12-2016-0140

Gunzel-Jensen F, Jain AK, Kjeldsen AM (2018) Distributed leadership in health care: the role of formal leadership styles and organizational efficacy. Leadership 14(1):110–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715016646441

Gao W, Wang L, Yan JD, Wu YX, Musse SY (2021) Fostering workplace innovation through CSR and authentic leadership: evidence from SME Sector. Sustainability 13(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105388

Hair J, Risher J, Sarstedt M, Ringle C (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Han J, Zhao Q, Zhang M (2016) China’s income inequality in the global context. Perspect Sci 7:24–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pisc.2015.11.006

Hu L, Bentler P (1999) Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6:1–55

Hulpia H, Devos G, Rosseel Y, Vlerick P (2012) Dimensions of distributed leadership and the impact on teachers’ organizational commitment: a study in secondary education. J Appl Soc Psychol 42(7):1745–1784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00917.x

Hester H, Geert D, Hilde VK (2009) The Influence of distributed leadership on teachers’ organizational commitment: a multilevel approach. J Educ Res 103(1):40–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670903231201

Hulpia H, Devos G (2010) How distributed leadership can make a difference in teachers’ organizational commitment? A qualitative study. Teach Teacher Educ 26(3):565–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.08.006

Harris A (2013) Distributed leadership: friend or foe? Educ Manag Adm Leadersh 41(5):545–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213497635

Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D (2010) A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods 15:309–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020761

Ingersoll R, May H (2012) The magnitude, destinations, and determinants of mathematics and science teacher turnover. Educ Eval Policy Anal 34(4):435–464. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373712454326

Ingersoll RM, Merrill E, Stuckey D, Collins G (2018) Seven Trends: the transformation of the teaching force—updated October 2018. CPRE Research Reports

İnandı Y, Yaman Ş, Ataş M (2022) The relation between career barriers faced by teachers & level of stress and job satisfaction. Particip Educ Res 9(2):240–260. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.22.38.9.2

Johnson SM, Kraft MA, Papay JP (2012) How context matters in high-need schools: the effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teachers College Record 114(10):1–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811211401004

Karabiyik B, Korumaz M(2014) Relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy perceptions and job satisfaction level. 5TH World conference on educational sciences Procedia—Soc Behav Sci 116:826–830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.305

Kavanoz S, Yüksel HG, Özcan E (2015) Pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy perceptions on Web Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Comput Educ 85(C):94–101

Klassen RM, Chiu MM (2010) Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. J Educ Psychol 102(3):741–756. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019237

Lauermann F, Johannes K (2016) Teachers’ professional competence and wellbeing: understanding the links between general pedagogical knowledge, self-efficacy and burnout. Learn Instr 45:9–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.06.006

Li RX, Liu HR, Chen YX, Yao ML (2019) Teacher engagement and self-efficacy: the mediating role of continuing professional development and moderating role of teaching experience. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00575-5

Liu J (2021) Exploring teacher attrition in urban China through interplay of wages and well-being. Educ Urban Soc 53(7):807–830. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124520958410

Liu J, Du J (2022) Identifying information friction in teacher professional development: insights from teacher-reported need and satisfaction. J Educ Teach 48(5):1–11

Liu J, Xie J (2021) Invisible shifts in and out of the classroom: dynamics of teacher salary and teacher supply in urban China. Teachers College Record 123:1–38

Liu J, Steiner-Khamsi G (2020) Human Capital Index and the hidden penalty for non-participation in ILSAs. Int J Educ Dev 73:102149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.102149

Liu Y, Bellibas MS, Gumus S (2021) The effect of instructional leadership and distributed leadership on teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: mediating roles of supportive school culture and teacher collaboration. Educ Manag Adm Leadersh 49(3):430–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220910438

Liu S, Onwuegbuzie A (2012) Chinese teachers’ work stress and their turnover intention. Int J Educ Res 53:160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.03.006

Liu Y, Werblow J (2019) The operation of distributed leadership and the relationship with organizational commitment and job satisfaction of principals and teachers: a multi-level model and meta-analysis using the 2013 TALIS data. Int J Educ Res 96:41–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.05.005

Malloy J, Leithwood K (2017) Effects of distributed leadership on school academic press and student achievement. In: Leithwood K, Sun J, Pollock K (eds) How school leaders contribute to student success. Stud Educ Leadersh 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50980-85

McInerney D, Korpershoek H, Wang H, Morin A (2018) Teachers’ occupational attributes and their psychological wellbeing, job satisfaction, occupational self-concept and quitting intentions. Teach Teacher Educ 71:145–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.020

Marchese M et al. (2019) Enhancing SME productivity: policy highlights on the role of managerial skills, workforce skills and business linkages, OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Papers, No. 16. OECD Publishing, Paris

OECD (2018) TALIS 2018 technical report. OECD Publishing, Paris

Peurach D, Cohen D, Yurkofsky M, Spillane J (2019) From mass schooling to education systems: changing patterns in the organization and management of instruction. Rev Res Educ 43(1):32–67

Perera H, Vosicka L, Granziera H, McIlveen P (2018) Towards an integrative perspective on the structure of teacher work engagement. J Vocat Behav 108:28–41

Saloviita T, Pakarinen E (2021) Teacher burnout explained: teacher-, student-, and organization-level variables. Teach Teacher Educ 97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103221

Shen J, Leslie J, Spybrook J, Ma X (2012) Are principal background and school processes related to teacher job satisfaction? A multilevel study using schools and staffing survey 2003–04. Am Educ Res J 49(2):200–230

Simon NS, Johnson SM (2015) Teacher turnover in high-poverty schools: what we know and can do. Teachers College Record 117(3):1–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811511700305

Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S (2010) Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: a study of relations. Teach Teacher Educ 26:1059–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.001

Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S (2014) Teacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion. Psychol Rep 114:68–77. https://doi.org/10.2466/14.02.PR0.114k14w0

Sun AN, Xia JG (2018) Teacher-perceived distributed leadership, teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction: a multilevel SEM approach using the 2013 TALIS data. Int J Educ Res 92:86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2018.09.006

Sutcher L, Darling-Hammond L, Carver-Thomas D (2016) A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the US. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/247.242

Torres DG (2018) Distributed leadership and teacher job satisfaction in Singapore. J Educ Adm 56(1):127–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-12-2016-0140

Torres DG (2019) Distributed leadership, professional collaboration, and teachers’ job satisfaction in U.S. schools. Teach Teacher Educ 79:111–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.12.001

Toropova A, Myrberg E, Johansson S (2020) Teacher job satisfaction: the importance of school working conditions and teacher characteristics. Educ Rev 73(1):71–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2019.1705247

Thomas WH, Feldman DC (2014) Subjective career success: a meta-analytic review. J Vocat Behav 85(2):169–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.06.001

Vieluf S, Kunter M, van de Vijver FJR (2013) Teacher self-efficacy in cross-national perspective. Teach Teacher Educ 35:92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.05.006

Wang H, Hall NC, Rahimi S (2015) Self-efficacy and causal attributions in teachers: effects on burnout, job satisfaction, illness, and quitting intentions. Teach Teacher Educ 47:120–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.005

Xu SH, Zhang HM, Dai Y, Ma J, Lyu L (2021) Distributed leadership and new generation employees’ proactive behavior: roles of idiosyncratic deals and meaningfulness of work. Front Psychol 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.755513

Zee M, Koomen H (2016) Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: a synthesis of 40 years of research. Rev Educ Res 86(2):672–681

Zheng X, Yin HB, Liu Y (2019) The relationship between distributed leadership and teacher efficacy in China: the mediation of satisfaction and trust. Asia-Pacif Educ Res 28(6):509–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-019-00451-7

Acknowledgements

JL is supported by a grant from the China Center for Education Quality Assessment [Grant ID: 202205059BZPK01].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author conceived and designed the study, and conducted the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to drafting the article and interpretation of results. All authors have revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and have read and agreed to the present version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study does not contain any interaction with human participants performed by any of the authors. Research ethics was overseen by the Institutional Review Board at Shaanxi Normal University.

Informed consent

No human subjects are involved in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Qiang, F. & Kang, H. Distributed leadership, self-efficacy and wellbeing in schools: A study of relations among teachers in Shanghai. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 248 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01696-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01696-w