Abstract

The responsibilities of teachers and principals in Government Funded Religious Schools (GFRS) in Malaysia have become more demanding as the enrolment rates have risen over time. The principals’ transformational leadership (TL) potentially affects teachers’ trust (TT), which directly influences their work commitment (WC) in school. However, limited evidence is available to support this assertion. Thus, this study seeks to investigate: (a) the level of TL, TT, and WC and (b) the influence of TT as a mediator between TL and WC from the teachers’ perspective in the Government Funded Religious Schools (GFRS) in Selangor. This study employed a survey research design. A survey questionnaire was administered to 297 GFRS teachers in Selangor. These teachers were selected using a stratified random sampling technique. Descriptive (means, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage) and inferential statistics (analysis of regression and predictive accuracy) were employed to analyse the data. The findings suggested that the overall level TL (M = 4.077, SD = 0.533), TT (M = 4.070, SD = 0.521) and WC (M = 4.188, SD = 0.413) in GFRS in Selangor were ‘high’. It was also found that TL was a significant predictor of TT (B = 0.867, SE = 0.026, p < 0.05) and WC (B = 0.361, SE = 0.083, p < 0.05), with approximately 29% of the variance in WC accounted for by TL (R2 = 0.290). However, TT was not a significant predictor of WC (B = 0.064, SE = 0.085, p > 0.05), suggesting that TT did not mediate the relationship between TL and WC. Even though this study exemplified that the level of TL, TT and WC was at a high level, TT was found to have an insignificant effect on WC. This provides a new insight in understanding this complex relationship. The dynamic of relationships—among teachers, between teachers and staff, and with outside parties, might have an impact on developing TT and WC among these teachers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To remain competitive and ensure their long-term survival, organisations face various challenges with respect to their leadership. The concept of leadership is closely related to the context in which leadership styles are practised and their effects on the organisation. In national education systems, the efficacy of changes is often associated with excellent leadership, quality of teachers, and the performance of students in schools.

School leadership and teachers’ commitment are among the components that uphold school performance in parallel with the success of a school. An absence of these may diminish the efforts of a school to achieve its aims and objectives. Strong leadership will increase teachers’ trust in principals, significantly enhancing their commitment to give their best to the school (Andriani et al., 2018). According to Criswell et al. (2018), if leaders manage to win the hearts and feelings of their subordinates, their instructions will be regarded as a form of stimulation and encouragement. This means that, as school leaders, principals should be aware of their actions and attitudes in order to earn and sustain teachers’ trust, rendering them leaders who are praised, loved, and respected by their subordinates.

Previous research by Li et al. (2016) found that teachers’ trust in their principals serves as mediator of a number of variables. Most experts have focused on the role of trust in the leader-subordinate relationship (Mangundjaya and Adiansyah, 2018). The level of trust that teachers have in their leaders is an important factor in schools as it influences their attitudes and behaviour towards any instructions given. This relationship is also emphasised in Social Exchange Theory, which states that the relationship established between individuals is often sustained by the element of trust (Blau, 1964). For instance, Norwani et al. (2016) found that trust in leaders has the ability to create effective feedback in relation to guidance communications.

Teachers’ commitment is autonomy to the implementation of teaching and learning, variation in teachers’ tasks and responsibilities, style of management, effectiveness of communication, and in-service training. Notably, in both high-performing and low-performing secondary schools, there is no significant difference in the level of commitment among teachers towards the organisation (Mohamad et al., 2016).

Teachers often encounter the challenge of having to manage their time and plan the best strategy to educate students while also shaping students’ morals and attitudes. Because the workload of teachers is challenging, principals need to adopt a relevant leadership style in order to sustain teachers’ commitment to the organisation (Peretomode and Bello, 2018). This is because leadership style determines teachers’ level of readiness to accept any assigned tasks and subsequently sustains their commitment to their workplace (Ismail, 2015). Principals who fail to lead their schools effectively may potentially face issues related to teachers’ emotions such as dissatisfaction, distrust, anger, and emotional stress (Andriani et al., 2018). Eliophotou-Menon and Ioannouz (2016) suggest that the majority of excellent schools are incapable of maintaining their performance in subsequent years following a decrease in teachers’ working commitment. Furthermore, a study by Peretomode and Bello (2018) demonstrated that teachers’ commitment to conducting their work is strongly affected by school leaders and the working environment.

Leadership refers to the ability to inspire confidence and support among followers for the purpose of achieving organisational aims. Yahaya and Ebrahim (2016) found that the leadership practices adopted by principals have the ability to impact teachers’ level of commitment as good leaders tend to be favoured by members of the organisation. Conversely, ineffective leaders will generate dissatisfaction among their followers. Moreover, one of the common problems encountered at schools and a dilemma for teachers and schools is the differing leadership practices, attitudes, and strategies adopted by principals and headmasters.

In Malaysian education, Government Funded Religious Schools have emerged as one of the most sought-after educational institutions (Azizi and Supyan, 2008; Sulehan, 2013). GFRS enrolment continues to rise year after year, with 16118 students and 1303 teachers currently enroled across all 23 GFRS (Ministry of Education Malaysia, 2018). This is due to the parents’ belief that this religious school is the best educational platform for producing students with a strong foundation of academic and religious knowledge and skills, as well as a positive personality and attitude (Amin and Jasmi, 2012; Hussian and Mansor, 2015). Therefore, these parents highly entrust the GFRS to achieve these aims (Azizi and Supyan, 2008; Sulehan, 2013).

It is critical for teachers in GFRS to meet the demands of parents while also dealing with a larger number of students in these institutions. According to Ismail (2015), the roles of teachers have become more demanding as enrolment exceeds that of mainstream education institutions. As a result of the current situation, the principal must play an effective role in managing teachers’ workload, needs, and motivation, as the current situation may have resulted in poor working commitment and teaching delivery quality. Thus, the principal’s transformational leadership is critical in ensuring that workload management and teacher motivation are effectively addressed.

Interestingly, previous studies on the GFRS principals’ transformational leadership provided dispersed findings. Abdullah (2016) found that the principals’ transformational leadership and teachers’ working commitment among teachers in Perak GFRS was at a high level. However, Mohamad Adnan et al. (2016) found that the teachers’ commitment to their profession, school, and teaching and learning was lower compared to the commitment to students in Kelantan GFRS. Similarly, Abdullah and Mansor (2014) discovered that despite their principals’ transformational leadership being at a high level, teachers’ working commitment in Negeri Sembilan GFRS was at an average level. To get a better understanding of this complex relationship, it is necessary to investigate transformational leadership practices among principals in order to determine if they may enhance teachers’ trust in their principals and subsequently improve their working commitment. Furthermore, the findings of this study are important to fill the gap of the literature as most studies were conducted in non-educational context and the exploration of this complex relationship in school context remains understudied (Zeinabadi and Rastegarpour, 2010).

Leadership, teacher’s trust and working commitment

The definition of leadership is broad and has been extensively discussed. In this study, it is defined as the process of influencing followers to mutually understand and accept the assigned tasks, ensuring they can be delivered successfully and efficiently (Yue et al., 2019). Leaders are responsible for formulating the vision and mission of their organisation, informing their followers about these, and successfully encouraging all members in the organisation to work together and invest significant effort to achieve these objectives. Leadership thus involves the process of constructing and planning the direction of the organisation based on the latest changes by utilising technological advancement, networking, establishing relationships, motivating and inspiring, and building confidence (Eliophotou-Menon and Ioannouz, 2016). In this research, leadership refers to principals’ efforts to influence and motivate teachers to make their best commitment to achieving the mission and vision of the organisation.

Teachers’ trust in principals is vital as this influences their attitudes and actions with respect to any assigned tasks. This aligns with previous studies demonstrating that teachers’ trust in the management and organisation of schools is important as it influences their attitudes to any decisions made by the school. According to Kim and Kim (2014), trust in leaders is essential as it forms the basis for a productive school. Ghamrawi (2013) asserts that school leaders may not be able to lead efficiently in the absence of trust from teachers. Similarly, Fairman and Mackenzie (2015) argue that teachers’ trust in principals can encourage open interactions between teachers and principals, which gives teachers the impression that the principals are trustworthy, honest, efficient, and caring. Teachers’ trust in principals is also vital in enhancing teachers’ self-efficacy (Lai, Luen and Chai, 2014). The relationship between teachers and principals is an important factor in enabling significant and sustainable changes to happen within schools. This is because school leaders will not be able to deliver effective leadership without gaining trust from their followers (Li et al., 2016).

Commitment can be defined as the agreement among members of an organisation to the mission and vision along with their willingness to continue serving and displaying strong loyalty to the organisation (Li et al., 2019). If a member possesses no commitment to the organisation, this will create numerous issues such as poor-quality work, attendance and disciplinary issues, reduced contribution to the success of the school, and reluctance to cooperate with other members within the organisation.

Thus, transformation leadership is critical for developing teachers’ trust and working commitment. Bushra (2011) discovered that transformation leadership is critical to a school’s success and quality outcomes. The principal’s charisma, individual consideration, intellectual stimulation and motivational inspiration are among influential traits of transformational leadership (Abdullah, 2016). According to an earlier work by Bass (1985), these characteristics have the ability to influence how workers think, react, and behave, as well as motivate them to be committed to their job.

Purpose of the present study

The current study sought to investigate: a) the level of transformational leadership practices among principals (TL), teachers’ trust in principals (TT), and teachers’ working commitment (WC) from the perspective of GFRS teachers in Selangor, and b) the influence of TT as a mediator between TL and WC.

To achieve these objectives, the study aimed to answer the following research questions: (a) What is the level of TL, TT, and WC from the perspective of GFRS teachers in Selangor? and (b) What is the influence of TT as a mediator between TL and WC from the perspective of GFRS teachers in Selangor?

In this study, it is believed that TT was a mediator that mediates the relationship between TL and WC. Therefore, to analyse its influence of as a mediator between TL and WC, the following hypotheses were tested:

-

1.

H01: There is no positive and significant effect of TL on TT

-

2.

H02: There is no positive and significant effect of TT on WC

-

3.

H03: There is no positive and significant effect of TL on WC

-

4.

H04: The relationship between TL and WC is not positively and significantly mediated by TT.

Methodology

To answer the research question, a survey research design was adopted as this is suitable for quantitatively explaining a specific aspect of a target population (Glasow, 2005). Furthermore, Chua (2020) stated that the survey questionnaire is useful in gathering direct data from respondents and generalising the findings to the target population.

Participants

The population for this study comprised 1277 teachers across all 23 GFRS in Selangor (Data Terbuka, 2018). As suggested by Krejcie and Morgan (1970), a sample of 297 teachers were then selected using stratified random sampling. To determine the sample size for each stratum, the total target sample (S = 297) was divided by the total population (N = 1277) and multiplied by the number of instructors for each stratum. For instance, for Gombak district: (297 (total of required sample)/1277 (population)) X 106 (total of instructors in Gombak district) = 25 teachers to be randomly selected. Table 1 presents the distribution of research participants according to district.

The permission from the Education Policy Planning and Research Division, Ministry of Education Malaysia and Selangor Education Office was obtained before the data was collected. The survey was then administrated face-to-face to selected respondents across nine districts in Selangor. The number of respondents from each district is shown in the table above.

Instrument

The survey questionnaire was adapted from the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) Form 5X- Short (Avolio and Bass, 2004). The first section (Section A) elicited demographic information from the participants. Section B of the instrument assessed the TL through four leadership components: cultivate an ideal influence, stimulate intellectual thinking, develop individual-based judgments, and inspire motivation. (Slocum and Hellriegel, 2007). The items employed to measure TT (Section C) were adapted from the Trust in Teams and Trust in Leaders Scale (Blais and Thompson, 2009). Finally, items measuring WC (Section D) were adapted from the instrument developed by Mujir (2011) and Ami et al. (2016). This instrument uses the 5-item Likert scale as it is comprehensible and reliable (Chua 2020). There are four sections in this instrument and an overall total of 16 items (see Table 2).

Data analysis

First, a data cleaning process was performed to eliminate input errors. The expectation-maximisation approach was also adopted to address items to which there were no responses (Byrne, 2010; Osborne, 2014). Descriptive statistics were then employed to answer the first three research questions (What is the level of TL, TT, and WC from the perspective of GFRS teachers in in Selangor?). Frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations were calculated to describe the characteristics of the target sample (Chua, 2020; McMillan and Schumacher, 2001). Table 3 provides the interpretations of mean scores used to determine the level of the three variables (TL, TT, and WC), as suggested by Hamzah et al. (2016).

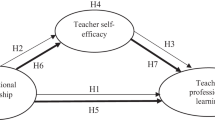

Inferential statistics (analysis of regression and predictive accuracy) were then utilised to determine the relationships between the three variables in this study: (a) transformational leadership practices among principals (TL), (b) teachers’ trust in principals (TT), and c) teachers’ commitment (WC) in GFRS in Selangor. The relationships between these variables are depicted in Fig. 1.

The review of the literature indicated that teachers’ trust in principals might affect the relationship between transformational TL and WC in GFRS in Selangor. To test this relationship, a mediation analysis was conducted based on Baron and Kenny’s (1986) causal procedure method. They proposed the following steps:

-

1.

ensure the independent variable (TL) significantly affects the dependent variable (WC)

-

2.

ensure the independent variable (TL) significantly affects the mediator (TT)

-

3.

ensure the mediator (TT) significantly affects the dependent variable (WC)

-

4.

ensure the effect of the independent variable (TL) is smaller after the addition of the mediator (TT) in the model.

Preacher and Heyes (2004), on the other hand, suggested using bootstrapping analysis to identify the mediation effect because this resampling procedure provides a more powerful and rigorous analysis (Zhao et al., 2010). Thus, in this study, bootstrapping with 5000 samples was conducted using PROCESS macro for SPSS (Darlington and Hayes, 2017). Predictive accuracy using the coefficient of determination (R2) was then tested to measure the amount of variance in the endogenous variables that was explained by the exogenous variables (Ramayah et al., 2018). According to Cohen (1988), the level of accuracy can be categorised as weak, moderate, and substantial (see Table 4).

Findings

Demographics of the research participants

Demographic information on the research participants is presented in Table 5. The majority of the participants were female (n = 245) and aged between 40 to 49 years old (n = 126). Most had working experience ranging between 11 to 15 years (n = 79) and had been working in their current school for six to ten years (n = 91).

The level of TL in GFRS in Selangor

To answer the first research question (what is the level of TL from the perspective of GFRS teachers in in Selangor?), the data were analysed to determine the means and standard deviations.

The findings in Table 6 indicate that all dimensions of TL were ‘high’ except for Inspire motivation, which achieved a ‘very high’ level (M = 4.272, SD = 0.559). The overall level of transformational leadership practices among principals in GFRS in Selangor was ‘high’ (M = 4.077, SD = 0.533).

The level of teachers’ trust in principals (TT) in GFRS in Selangor

To answer the second research question (what is the level of TT from the perspective of teachers in GFRS in Selangor?), the data were analysed to determine the means and standard deviations.

The findings in Table 7 indicate that all dimensions of TT were ‘high’ (M = 4.070, SD = 0.521) and that competence was the highest among the TT domains (M = 4.194, SD = 0.572). The overall level of teachers’ trust in principals in GFRS in Selangor was ‘high’ (M = 4.070, SD = 0.521).

The level of teachers’ working commitment (WC) in GFRS in Selangor

To answer the second research question (what is the level of WC from the perspective of GFRS teacher in Selangor?), the data were analysed to determine the means and standard deviations.

The findings in Table 8 indicate that all dimensions of WC were ‘high’ except for commitment towards the profession, which was ‘very high’ (M = 4.567, SD = 0.452). The overall level of working commitment in GFRS in Selangor was ‘high’ (M = 4.188, SD = 0.413).

The Influence of TT as a mediator in the relationship between TL and WC

To determine the influence of TT as a mediator in the relationship between TL and WC, an analysis of regression and predictive ability was conducted. Table 9 provides a summary of the mediation analysis results.

The results indicate that TL was a significant predictor of TT (B = 0.867, SE = 0.026, p < 0.05). Therefore, the first null hypothesis (H10: There is no positive and significant effect of TL on TT) was rejected. However, TT was not a significant predictor of WC (B = 0.064, SE = 0.085, p = 0.452), which supported the second null hypothesis (H20: There is no positive and significant effect of TT on WC). TL was a significant predictor of WC (B = 0.361, SE = 0.083, p < 0.05). Approximately 29% of the variance in WC was accounted for by TL (R2 = 0.290), indicating a substantial level of predictive accuracy (>0.26) (Cohen, 1988; Falk and Miller, 1992). Hence, the third null hypothesis (H30: There is no positive and significant effect of TL on WC) was rejected.

The indirect effect was tested using a percentile bootstrap estimation approach with 5000 samples. These results indicated that the indirect coefficient was not significant (B = 0.055, SE = 0.071, 95% CI = −0.080, 0.199). Hence, the fourth null hypothesis (H40: The relationship between TL and WC is not positively and significantly mediated by TT) was supported.

Discussion

The findings indicated that the level of transformational leadership practices among principals from the perspective of teachers was high (M = 4.272, SD = 0.559). The teachers believed that their principals had exhibited an ability to cultivate an ideal influence, stimulate intellectual thinking, develop individual-based judgments, and inspire motivation. The findings reflect the proposed dimensions of an excellent leader suggested by Slocum and Hellriegel (2007). Notably, the findings are also in line with previous studies on transformational leadership among principals in other public schools (Abdullah and Kassim, 2013; Shali, 2016; Abdullah, 2016). This suggests that the principals are extremely determined and thoughtful in creating a working environment that encourages intellectual development, motivation to work, and positive working habits.

The findings also indicated that the level of teachers’ trust in principals was high (M = 4.070, SD = 0.521). This suggests that the principals have exhibited a high level of integrity, concern, reliability, and competency at work. By contrast, Tahir and Yassin (2008) found that the teachers in public schools in Batu Pahat, Johor have only a moderate level of trust in their principals. Although they believed that the principals were the primary source of information essential for managing the schools, they also believed their commitment to work was important in enhancing the academic performance of schools. In this study, the teachers perceived that, in addition to being competent, their principals exhibited a high level of reliability, concern, and integrity. These are important factors in developing a more supportive and efficient working environment (Tschannen-Moran, 2004). Geist and Hoy (2004) noted that a high level of trust in principals will lead to more open interaction, which is essential for achieving goals as a team.

The results of this study also suggested that the level of working commitment was high (M = 4.188, SD = 0.413). Notably, commitment towards the profession was found to be very high (M = 4.567, SD = 0.452). In contrast, Abdullah and Mansor (2014) discovered that working commitment among GFRS teachers in Negeri Sembilan was at an average level, despite the fact that they considered their principals to have a high level of transformational leadership. This may be because Selangor GFRS principals consistently establish a pleasant working atmosphere that promotes professional commitment among teachers. Koon (2018) defined a positive working environment as one that is: (a) safe and hygienic, (b) allows teachers to have autonomy in implementing their teaching, (c) allocates reasonable duties and responsibilities, (d) is effective in its administration, and (e) provides in-service training for teachers. Consequently, these teachers have developed an affective, normative, and continuance commitment that contributes to a high level of working commitment in these institutions. In Allen and Meyer’s (1990) working commitment model, the affective, normative, and continuance commitment developed by workers will cultivate a sense of loyalty and willingness to contribute to the organisation.

The review of literature indicated that TL has a positive effect on TT (Li et al. 2019; Zeinabadi and Rastegarpour, 2010). Similarly, this study discovered that TL has a positive and significant effect on TT (B = 0.867, SE = 0.026, p < 0.05). This suggests that the transformational leadership exemplified by principals in these institutions has aided in the development of teachers’ trust in them. Abdullah (2016) agreed that the GFRS principal’s charisma, individual consideration, intellectual stimulation and motivational inspiration are pivotal in creating a positive working climate. According to Bass (1985) and Bass and Avolio (1994), an effective leader who demonstrates all four components of transformational leadership has the ability to influence his or her employees’ thinking, motivation, and behaviour. Furthermore, Zeinabadi and Rastegarpour’s (2010) model of Teacher Trust in Principal, which is based on Bass’s (1985) TL components, demonstrated that it has a substantial and direct impact on TT. In the context of this study, these principals were able to apply TL and, as a consequence, build teacher trust, which is consistent with Abdullah’s (2016) findings. Specifically, Abdullah (2016) discovered that the charisma, individual consideration, intellectual stimulation, and motivational inspiration of the GFRS principal are critical in establishing a positive working environment.

Undoubtedly, in this study, these principals have exhibited an ability to cultivate an ideal influence, stimulate intellectual thinking, develop individual-based judgments, and inspire motivation in their schools. As a result, teachers have developed trust in their principals. These teachers believed their principals were capable of not just appreciating, caring for, and supporting their efforts to the school, but also of continuously managing and successfully carrying out their duties in school. Clearly, the principals’ efforts have contributed to the development of trust in teachers and positive perceptions towards their leader (Li et al. 2019).

The results indicated that TL has a positive and significant effect on WC (B = 0.361, SE = 0.083, p < 0.05). Furthermore, approximately 29% of the variance in WC was accounted for by TL (R2 = 0.290), indicating a substantial level of predictive accuracy (>0.26) (Cohen, 1988; Falk and Miller, 1992). Previous studies (Al Yusfi, 2016; Andriani et al., 2018; Mangundjaya and Adiansyah, 2018) have similarly identified the effect of TL on WC. The principals in these institutions were therefore clearly able to motivate teachers to be committed towards their school, students, and profession. As described in Allen and Meyer’s (1990) working commitment model, psychological states, namely affective, normative, and continuance commitment, are important indicators in developing positive attitudes towards an organisation. They further elaborated that if the leader were able to develop a positive working environment, workers will develop a strong emotional attachment towards the job (affective commitment), a fear of losing their job due to benefits offered by the organisation (continuance commitment), and a sense of loyalty to their positions and company (normative commitment).

Although the importance of workers’ trust in developing a positive working commitment has been supported in the literature (Martins et al., 2017; Ndubisi 2011; Utami, 2014), the results in the current study indicated the opposite. For instance, TT has no positive and significant effect on WC (B = 0.064, SE = 0.085, p = 0.452). Furthermore, the mediation analysis indicated that the relationship between TL and WC was not positively and significantly mediated by TT (B = 0.055, SE = 0.071, 95% CI = −0.080, 0.199).

Previous researchers have defined trust as an intention to acknowledge vulnerability that is based on optimistic views of the actions taken by another party (Mishra 1996; Rousseau et al. 1998). Trust is developed according to how reliable, concerned, competent, and open principals are in exercising their leadership (Mishra, 1996). In this study, although teachers’ trust in principals was high, this did not predict their working commitment.

A possible explanation for this finding lies in how commitment is developed. Razak et al. (2010) argued that working commitment is a complex process that is influenced by the dynamics of the group and is contextually contingent. In this study, the dimension of working commitment only focused on commitment towards school, students, and the profession. It may be the case that other external factors such as the dynamics among teachers, between teachers and staff, and between teachers and parents might also influence their working commitment. Ni (2017) argued that teachers are not only connected to their classrooms, they also have relationships with colleagues, students, society, and the profession, which makes the establishment of working commitment a dynamic process.

Another contributing factor to working commitment is working conditions (Firestone and Pennell, 1993; Ni, 2017). For instance, teachers’ heavy workload might affect how they perceive their working commitment. Ni (2017) further elaborated that a reasonable teaching load will help teachers to be more fully engaged and motivated in teaching. Umar et al. (2012) noted that in GFRS in Malaysia, teachers’ workload is burdensome as some of the teaching duties overlap with administrative works. Therefore, their working commitment might be affected even though they are committed towards students, the school, and the profession.

Implication and limitation of the study

The GFRS principals need to practice TL in ensuring the TT and WC are at a high level. The findings of this study indicated that the teachers have a high level of TT and WC and perceived that their principals were able to practice TL. This provides valuable information for the ministry and stakeholders to constantly provide training or support in ensuring the future principals are able to practise transformative leadership in schools. However, the findings should not be generalised to other educational institutions in Malaysia since the respondents were teachers in Selangor GFRS. Thus, it is recommended for future researchers to consider a larger sampling and explore this similar issue from the perspective of principals.

Conclusion

In this study, the aims were to identify (a) the level of TT, TL, and WC among GFRS teachers in Selangor, and (b) the influence of TT as a mediator between TL and WC. Generally, teachers perceived the levels of TL, TC, and WL to be at a high level. Furthermore, TL was found to have a positive and significant effect on TT. The effect of TL on WC was also significant and positive. However, TT was found to have an insignificant effect on WC and thus was not a mediator for the relationship between TL and WC. Even though this finding was not in line with previous studies, this did not indicate that TT was less important in developing WC. The literature has indicated that the development of working commitment is complex and influenced by various factors, including group dynamics and the working conditions in an organisation (Firestone and Pennell, 1993; Ni, 2017; Razak et al., 2010). It is believed that these factors might have affected the relationship between trust in principals and working commitment.

Much can be learnt from this unique finding. The study has provided a direction for future research to investigate the dynamics of relationships among teachers, between teachers and staff, and possibly other relevant parties outside the school. It will also be important to explore the workloads of teachers in GFRS as this might provide a deeper understanding of the relationship between teachers’ trust in principals and positive working commitment.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality of the respondents’ information but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abdullah T (2016) Amalan Kepimpinan Transfrormasional Pengetua dan Kepuasan Kerja Guru di SABK Negeri Perak. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia

Abdullah T, Mansor AN (2014) amalan kepimpinan transformasional pengetua dan kepuasan kerja guru di Sekolah Menengah Agama Bantuan Kerajaan (SABK) Negeri Sembilan. Int Semin Global Educ II 4:2426–2439. ISBN 978-983-2267-91-1

Abdullah JB, Kassim JB (2013) Amalan Kepimpinan Instruksional Dalam Kalangan Pengetua Sekolah Menengah di Negeri Pahang: Satu Kajian Kualitatif. (Doctoral dissertation, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia). Retrieved from http://eprints.iab.edu.my/v2/427/

Al Yusfi A (2016) Pengaruh kepemimpinan transformasional dan komitmen organisasi terhadap organizational citizenship behavior guru SMP negeri di Jakarta Selatan. Jurnal Manajemen Pendidikan 7:1225–1233. https://doi.org/10.21009/jmp.07104

Allen NJ, Meyer JP (1990) The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J Occup Psychol 63(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

Ami NASNZ, Johari FM, Rahman NA, Yaacob SUM, Yahaya Z (2016) Efikasi Pengajaran Vokasional dalam Penerapan Kemahiran Berfikir Abad Ke 21. Jabatan Hospitaliti, IPG Kampus Pendidikan Teknik Bandar Enstek, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia

Andriani S, Kesumawati N, Kristiawan M (2018) The Influence of The Transformational Leadership and Work Motivation on Teachers Performance. Int J Sci Technol Res 7/7:19–29

Avolio BJ, Bass BM (2004) Multifactor leadership questionnaire: Manual and sampler set, 3rd edn. Mind Garden, Inc, Menlo Park

Azizi U, Supyan H (2008) Peranan kerajaan negeri dan pusat ke atas sekolah agama rakyat: suatu kajian masalah pengurusan bersama terhadap pemilikan kuasa. Jurnal Pengurusan dan Kepimpinan Pendidikan 18/2:19–40

Amin MH, Jasmi KA (2012) Sekolah Agama di Malaysia: sejarah, isu dan cabaran. UTM Press, Johor Bahru, ISBN: 978-983-52-0791-4

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Person Soc Psychol 51/6:1173–1182

Bass BM (1985) Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Collier Macmillan Publishers, New York, NY

Bass BM, Avolio BJ (1994) Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Blais A, Thompson M (2009) The trust in teams and trust in leaders scale: a review of their psychometric properties and item selection. Defence Research and Development Canada, Toronto, Canada

Blau P (1964) Exchange and power in social life. Wiley, New York, NY

Bushra F (2011) Effect of transformational leadership on employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment in banking sector of Lahore (Pakistan). Int J Bus Soc Sci 2/18:261–267

Byrne MB (2010) Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd edn.). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, New York, NY

Chua YP (2020) Mastering research methods (3rd edn.). McGraw-Hill Education, Kuala Lumpur

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

Criswell BA, Rushton GT, Nachtigall D, Staggs S, Alemdar M, Cappelli CJ (2018) Strengthening the vision: Examining the understanding of a framework for teacher leadership development by experienced science teachers. Sci Educ 102/6:1265–1287. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21472

Darlington RB, Hayes AF (2017) Regression analysis and linear model: concepts, applications, and implementation. The Guildford Press, New York, NY

Data Terbuka (2018) Bilangan Guru Mengikut Sekolah dan PPD di Selangor. Retrieved from https://www.data.gov.my/data/ms_MY/dataset/bilangan-guru-selangor/resource/b2ed2175-36c8-4d33-bac6-3eec8d167ff4

Eliophotou-Menon M, Ioannouz A (2016) The link between transformational leadership and teachers’ job satisfaction, commitment, motivation to learn, and trust in the leader. Acad Educ Leadersh J 20/3:12–22. https://gnosis.library.ucy.ac.cy/handle/7/37924

Fairman JC, Mackenzie SV (2015) How teacher leaders influence others and understand their leadership. Int J Leadersh Educ 18:61–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2014.90400

Falk RF Miller NB (1992) A primer for soft modelling. Akron, OH: University of Akron Press

Firestone WA, Pennell JR (1993) Teacher commitment, working conditions, and differential incentive policies. Rev Educ Res 63/4:489–525. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170498

Geist JR, Hoy WK (2004) Cultivating a culture of trust: Enabling school structure, teacher professionalism, and academic press. Lead Manag 10/2:1–17

Ghamrawi N (2013) In principle, it is not only the principal! Teacher leadership architecture in schools. Int Educ Stud 6/2:148–159. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v6n2p148

Glasow PA (2005) Fundamentals of survey research. MITRE, Washington

Hamzah MI, Juraime F, Mansor AN (2016) Malaysian principals’ technology leadership practices and curriculum management. Creat Educ 7:922–930. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.77096

Hussian SM Mansor AN (2015) Amalan Kepimpinan Lestari Dan Hubungannya Dengan Komitmen Guru Kolej Islam Sultan Ahmad Shah, Klang. International Seminar on Global Education III, 1, 1119–1131. ISBN 9786027052512

Ismail FN (2015) Effects of ethical climate on organizational commitment, professional commitment and job satisfaction of auditor in Malaysia. Gadjah Mada Int J Bus 17/2:139–155. https://doi.org/10.22146/gamaijb.6907

Kim S, Kim J (2014) Integration strategy, transformational leadership and organizational commitment in korea’s coorporate split -offs. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci 109:1353–1364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.637

Koon TL (2018) Faktor dalaman sekolah dan komitmen guru terhadap organisasi: pengaruh pengantara kualiti kehidupan kerja guru di SBT dan SBBT. (Doctoral dissertation, Universiti Sains Malaysia). Retrieved from http://eprints.usm.my/43764/

Krejcie R Morgan D (1970) Sample size determination using Krejcie and Morgan table. Retrieved from http://www.kenpro.org/sample-size-determination-using-krejcie-and-morgan-table/

Lai TT, Luen WK, Chai LT (2014) School principal leadership styles and teacher organisational commitment among performing schools. J Glob Bus Manag 10/2:67–75

Li H, Sajjad N, Wang Q, Ali AM, Khaqan Z, Aminah S (2019) Influence of transformational leadership on employees’ innovative work behavior in sustainable organisations: test of mediation and moderation processes. Sustainability 11/6:1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11061594

Li L, Hallinger P, Walker A (2016) Exploring the mediating effects of trust on principal leadership and teacher professional learning in Hong Kong primary schools. Educ Manag Admin Leadersh 44:20–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214558577

Mangundjaya WL, Adiansyah A (2018) The impact of trust on transformational leadership and commitment to change. Adv Sci Lett 24:493–496. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2018.12048

Martins DM, Faria AC, Prearo LC, Arruda AGS (2017) The level of influence of trust, commitment, cooperation, and power in the inter-organizational relationships of Brazilian credit cooperatives. Re vista de Administração 52:47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rausp.2016.09.003

McMillan JH, Schumacher S (2001) Research in education: a conceptual introduction (5th ed.). Longman, Boston

Ministry of Education Malaysia (2018) Malaysia educational statistics. Retrieved from: https://www.moe.gov.my/muat-turun/penerbitan-dan-jurnal/terbitan/buku-informasi/1578-buku-perangkaan-kpm-2018/file

Mishra AK (1996) Organisational responses to crisis: The centrality of trust. Kramer. In: Roderick M, Tyler T (eds.) Trust in Organisations. Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 261–287

Mohamad R, Kasim AL, Zakaria S, Nasir FM (2016) Komitmen Guru dan Kepuasan Kerja Guru di Sekolah Menengah Harian Berprestasi Tinggi dan Berprestasi Rendah di Daerah Kota Bharu, Kelantan. Proceeding of ICECRS, 1, 863–874. International Seminar on Generating Knowledge Through Research, UUM-UMSIDA, http://ojs.umsida.ac.id/ index.php/icecrs, https://doi.org/10.21070/picecrs.v1i1.603

Mohamad Adnan MK, Siti Noor I, Suhaila M, Hasliza I (2016) Iklim sekolah dan komitmen guru di Sekolah Agama Bantuan Kerajaan (SABK) Negeri Kelantan. Proceeding of ICERS 1(1):699–708. https://doi.org/10.21070/picecrs.v1i1.543

Mujir SJM (2011) Impak kepimpinan multidimensi, pemikiran strategik. dan keberkesanan kepimpinan ketua jabatan politeknik malaysia kepada komitmen kerja pensyarah. (Doctoral dissertation, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia). Retrieved from http://myto.upm.edu.my/find/Record/ukmvital-74318

Ndubisi NO (2011) Conflict handling, trust and commitment in outsourcing relationship: A Chinese and Indian study. Indust Market Manag 40:109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.09.015

Ni Y (2017) Teacher working conditions, teacher commitment, and charter schools. Teach Coll Rec 119/6:1–38

Norwani NM, Yusof H, Mansor M, Daud WMNWM (2016) Development of teacher leadership guiding principles in preparing teachers for the future. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci 6/12:374–388. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v6-i12/2503

Osborne JW (2014) Best practices in exploratory factor analysis. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, Middletown, DE

Peretomode VF, Bello SO (2018) Analysis of teachers’ commitment and dimensions of organisational commitment in Edo State Public Secondary Schools. J Educ Soc Res 8/3:87–92. https://doi.org/10.2478/jesr-2018-0034

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2004) SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Method Instrum Comput 36:717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553

Ramayah T, Cheah J, Chuah F, Ting H, Memon MA (2018) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.0: An updated and practical guide to statistical analysis (2nd edn.). Pearson Malaysia Sdn. Bhd, Kuala Lumpur

Razak NA, Darmawan IGN, Keeves JP (2010) The influence of culture on teacher commitment. Soc Psychol Educ 13/2:185–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-009-9109-z

Rousseau DM, Sitkinn SB, Burt RS, Camerer C (1998) Not so different after all: a cross discipline view of trust. Acad Manag Rev 23/3:393–404. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926617

Shali KKS (2016) Amalan kepimpinan transformasi guru besar dan kualiti pengurusan sekolah rendah di Perlis. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia

Slocum JW, Hellriegel D (2007) Fundamentals of organizational behavior. Cengage Learning, India

Sulehan F (2013) Amalan kepimpinan lestari pengetua Sekolah Agama Bantuan Kerajaan (SABK) di Daerah Pontian [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Universiti Teknologi MARA

Tahir LM, Yassin MA (2008) Impak psikologi guru hasil kepimpinan pengetua. Jurnal Teknologi 48:129–139. https://doi.org/10.11113/jt.v48.250

Tschannen-Moran M (2004) Trust matters: leadership for successful schools. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Umar A, Jamsari EA, Hassan WZW, Sulaiman A, Muslim N, Mohamad Z (2012) Appointment as principal of government-aided religious school (SABK) in Malaysia. Aust J Basic Appl Sci 6/10:417–423

Utami AF, Bangun YR, Lantu DC (2014) Understanding the role of emotional intelligence and trust to the relationship between organizational politics and organizational commitment. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci 115:378–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.444

Yahaya R, Ebrahim F (2016) Leadership styles and organisational commitment: literature review. J Manag Dev 35/2:190–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-01-2015-0004

Yue CA, Men LR, Ferguson MA (2019) Bridging transformational leadership, transparent communication, and employee openness to change: The mediating role of trust. Public Relat Rev 45/3:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.04.012

Zeinabadi H, Rastegarpour H (2010) Factors affecting teacher trust in principal: testing the effect of transformational leadership and procedural justice. Procedia Social Behav Sci 5:1004–1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.226

Zhao X, Lynch JG, Chen Q (2010) Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res 37/2:197–206

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interest exists.

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from the Education Policy Planning and Research Division, Ministry of Education Malaysia and Selangor Education before the data was collected.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the data was collected.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mansor, A.N., Abdullah, R. & Jamaludin, K.A. The influence of transformational leadership and teachers’ trust in principals on teachers’ working commitment. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 302 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00985-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00985-6