Abstract

Children’s literature on the topic of breastfeeding is a niche form of media that has the potential to present breastfeeding in a different light because of a difference in audience and intent, but this media form is understudied. The aim of this study was to explore the portrayal of breastfeeding in English language children’s literature published between 1985 and 2020. This cross-sectional qualitative study explored the written and visual content of children’s literature on the topic of breastfeeding. This qualitative study utilized content analysis to explore 49 children’s books that depict breastfeeding as a major theme or story. Children’s books depict breastfeeding as an act of love that confers benefits beyond nutrition including being a symbolic gift, and conferring growth, and love. Breastfeeding is presented in these books by teaching how mammals feed their young or by teaching children about the function of breasts. These books also often include information for parents. Children’s literature depicting breastfeeding provides a unique avenue for the dissemination of breastfeeding resources and information. This research can inform lactation education practices in healthcare settings by normalizing breastfeeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breastfeeding is important for maternal and child health and increasing breastfeeding is a public health priority (Azad et al., 2020). Media representations “help define what is considered ‘normal’ about infant feeding” and can influence whether breastfeeding is considered an unacceptable spectacle or an everyday event (Foss, 2017, p. 12). Exposure to media depicting breastfeeding can improve attitudes and support for breastfeeding (Foss and Blake, 2019).

Children’s literature has problematic portrayals of infant feeding. In an analysis of children’s literature on the topic of a new baby, Foss (2017) found that bottle-feeding, presumably formula feeding, is presented as normal and is the most commonly depicted means of feeding a baby. Bottles are either in the background of baby care images or are shown being used to feed babies and even animal babies. While a few books depict breastfeeding, this is not messaging common in most children’s literature about new babies. Woodstein (2022) compared 29 English-language picture books about breastfeeding to Swedish books on the same topic. English books were rare and were often “new baby works” or were very pro-breastfeeding (Woodstein, 2022, p. 32). Discretion in breastfeeding was common, with possibilities for images to be interpreted in different ways (Woodstein, 2022). Images of babies could be interpreted as cuddling close to the chest or the same image might be interpreted as breastfeeding (Woodstein, 2022). In addition, Woodstein (2022) found that 44% of English-language books sampled in the study depicted bottle feeding. Overall, Swedish books were more accurate in depicting breastfeeding (e.g. latching) and were more explicit in showing the breast (Woodstein, 2022). The Swedish books also portrayed breastfeeding more and bottles less than books in English (Woodstein, 2022). In an American context, Altshuler (1995) examined books depicting breastfeeding. Similar to Woodstein (2022), Altshuler (1995) found these books to often be in books about a new baby, although while Woodstein (2022) found English-langauge children’s books about breastfeeding to be rare, Altshuler commented that breastfeeding was presented in more recent works. Altshuler (1995) noted that while some depicted breastfeeding positively, others undermined breastfeeding, for example with images of breastfeeding paired with images of formula feeding, presenting them as if equal.

Cultural understandings and knowledge of breastfeeding arise in complex and various ways. The bioecological model of human development focuses on the interaction’s individuals have with the objects and symbols within their environment (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006). Books can be a source of new information for children, including information about biological facts and nutrition (Strouse et al., 2018). A bioecological framework is useful because it recognizes that individuals interact within the contexts of their environment (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006). Media can be viewed as a macrosystem of influence in two ways. First, media such as children’s literature reflects cultural breastfeeding norms of the cultural context it is published within. Second, media can influence infant feeding behaviors and attitudes. Media itself is also within the larger system of time, termed the chronosystem in bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006), influenced by the time it is created. Examination of breastfeeding depictions in children’s literature can identify what norms of breastfeeding are portrayed and can lead to an understanding of one media influence on breastfeeding attitudes.

Altshuler (1995) provided a commentary on breastfeeding in the specialized subject matter of breastfeeding in children’s literature, although this commentary now has many titles out of print. While Foss (2017) examined a broad sample of children’s books, only six books in the sample depicted breastfeeding. Woodstein (2022) examined English-language books about breastfeeding, with a focus on a United Kingdom context. The current study intended to fill the research gap on breastfeeding depictions in children’s literature in an American context by providing a contemporary empirical analysis of these books. The findings of this research can provide a current understanding and description of a form of media that depicts breastfeeding. The overall aim of the study was to explore the portrayal of breastfeeding in English language children’s literature published between 1985 and 2020.

Methods

This cross-sectional qualitative study explored the written and visual content of children’s literature on the topic of breastfeeding (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). This design was used to examine a diverse sample of books currently available on this topic.

Setting and relevant context

Children’s literature exposes children to a wide variety of ideas including race (Huber et al., 2020), political engagement (Patterson, 2019), and the transition to kindergarten (Cutler and Slicker, 2020). In the United States, while some readerships have stagnated, children’s literature continues to increase in sales (Short, 2018). Parents and families invest in books and recognize the importance of reading to children (Short, 2018). Shared reading is considered an important part of child development and literacy is considered a developmental domain, with efforts to increase children’s reading exposure including in healthcare settings (Klass et al., 2020; Logan et al., 2019). Literacy is associated with long-term positive outcomes including school readiness and career success, and is thought to begin development in infancy (Klass et al., 2020). Book publishing in the United States relies on market analysis and children are viewed as consumers and not readers (Short, 2018). Large conglomerates publish the majority of books in the United States with much fewer books published by independent publishers. While previous commentary has discussed the depiction of breastfeeding in children’s literature (Altshuler, 1995), there has been no recent empirical analysis of breastfeeding content in children’s literature examining books currently available in an American context.

Sample

The target population was children’s literature written in English with breastfeeding content. A purposive sampling method was used to identify an original sample of books (N = 53). The inclusion criteria were books that specifically covered breastfeeding. Breastfeeding was defined in this study as feeding at the breast or providing human milk through other feeding methods (Labbok and Starling, 2012). Books were included if they portrayed feeding formula if breastfeeding was also portrayed. Books for various children’s audiences (ages 0–12) were included, ranging from board books for infants to books appropriate for children that read independently. Books were excluded if they were aimed at older audiences (n = 2) or did not contain breastfeeding portrayals (n = 2). The final sampling included 49 children’s books available for sale or library lending in the United States (Table 1) on the topic of breastfeeding.

Data collection

Data collection began with searching various breastfeeding, parenting, and children’s book websites and blogs for recommendations about children’s books on the topic of breastfeeding. Search terms included “breastfeeding,” “weaning,” “mothers milk,” “nursing” and other variations of terms for breastfeeding, as well as “children’s books” and “children’s literature”. Online booksellers were also used to search for books pertaining to the topic, as well as conducting searches of public and university libraries. Sample recruitment concluded when no new book titles emerged in the search process. From October 2020 to May 2021 data were collected by the researcher starting with the creation of the book list and then a collection of the books in physical form or online versions (Table 2).

Interpretations were enriched by my own experiences as a mother that breastfed and reads to her young children. My positionality as an advocate for breastfeeding, training as a certified lactation counselor, and role of researcher and educator situated this work. I was sensitive to these identities, beliefs, and biases throughout data collection and analysis. For example, during data analysis, there was sensitivity to the emerging findings of positive portrayals along with my own positive beliefs about breastfeeding. Therefore, various rounds of iterative categorical coding explored the possibility that negative portrayals occurred but were missed.

Data analysis

Books ranged in publishing year from 1985 to 2020. Only one book sampled came from the 1980s (2%), four were published in the 1990s (8%), 17 were from the 2000s (35%), and 27 were from the 2010s to the present (55%). Breastfeeding was the main topic in 65% of the books (n = 32) and breastfeeding was depicted but not central to the story in 35% (n = 17). The books were hardback picture books (n = 20, 41%), paperback picture books (n = 19, 39%) and board books (n = 10, 20%).

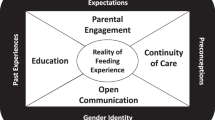

This study utilized content analysis to explore patterns in data moving from the concrete to the more abstract (Graneheim et al., 2017). In this study, inductive content analysis was used. Content analysis is a research methodology for the analysis of qualitative data focusing on subject, context, and variation and allows for opportunities to analyze descriptive (Neuendorf, 2017) as well as interpretative content (Graneheim et al., 2017). The entirety of each book was analyzed including covers, cover pages, and dust jackets.

Analysis followed an inductive process adapted from Neuendorf (2017) to explore how breastfeeding is portrayed (Table 3). A codebook was developed using open coding and categorical analysis. The code book included 25 parts, each a content category. Coding depended on the category, some codes were presence/absence (e.g., formula or bottles) and others were nominal data (e.g., names used to describe breast anatomy). The code book was edited and refined over several iterations and each book in the sample was coded individually. This coding instrument was analyzed thematically, leading to a grouping of the earlier categories into three emergent themes: unique breastfeeding situations depicted, the benefits of breastfeeding beyond nutrition, and educational depictions (Table 3).

Results

In the sample, many of the books had information directed toward parents (n = 19, 39%). Often this took the form of resources, letters from the author, and tips. A lengthy example of this is in Bye Bye Mommy’s Milk which has a “To the moms” section with 20 pages of weaning information and additional pages of resources (De Visscher, 2020, pp. 50–70). While a small proportion of the sample, a few books were bilingual and these paired English writing with Spanish (n = 3, 6%; Fox, 2018; Hackney, 2017; Michels, 2018). Most books used images that were illustrations, and only five books had photography images (10%).

The benefits of breastfeeding beyond nutrition

Books associated breastfeeding with gains that were not directly nutritional (e.g., positive emotions). Books (n = 18, 37%) portrayed associations of breastfeeding with growth or growing, described by Elder (2019) as “my milk helped you to grow” (p. 3) and by Michels (2001) with “breast milk gave me everything I needed to grow big” (p. 53). Breastfeeding was also associated with love. Love was sometimes discussed as something associated with breastfeeding, for example “in her loving arms I feed” (Moen, 1999, p. 4). It was also directly referred to as an act of love, called a “loving gift” (Hutton, 2015, p. 5), and explicitly explained with “breastfeeding isn’t just giving him food. It is also giving him love!” (de Aboititz, 2011, p. 9).

Breastfeeding was also described frequently as a gift or something shared. Breastfeeding was called “mother’s gift” (Fox, 2018, p. 17), and the book The Best Gifts is titled in reference to breastfeeding as a gift at the beginning and end of the story, among other gifts that “can never be bought” (Skrypuch, 2013, p. 25). Breastfeeding was also framed as the “best”. While best was used frequently, “my best way to show I love you” (Neyland, 2017, p. 13) and “my best food comes from mommy” (Moen, 1999, p. 2), and “mummy’s milk is best to eat,” (Moen, 1999, p. 8) other words were also used to describe similar ideas of best including perfect, wonderful, and precious.

Breastfeeding was also depicted as an emotional soother. Many books described how breastfeeding eased children’s emotional state when upset or hurt, “you’d fall and cry…Mummy scooped you up and nursed you” (Gabler, 2016, p. 15). In I Like to Nurse, emotions are soothed with the description of how the character likes to “nurse when I am feeling sad. It helps me feel a little better” (Brundidge, 2015, p. 25). Books also framed breastfeeding as the only food babies need, and the “only food that some babies receive all day” (Purnell-O’Neal, 2005, p. 4). Safety was also frequently mentioned. Safety conferred by human milk was described in a variety of ways including the provision of health, strength, and protection. Sometimes this safety was framed as something related to breastfeeding, for example “he feels safe and at peace” (de Aboititz, 2011, p. 9). Other books were more specific with how breastfeeding directly confers safety, describing “infection fighting cells” and “antibodies” (Brown, 2016, p. 12). Breastfeeding was also described as having “healing power and can cure most anything” (Purnell-O’Neal, 2005, p. 4). Comfort was a term used frequently, for example “suckling for comfort” (Neyland, 2017, p. 5) and in the title and general theme within Dillemuth’s (2017) Loving Comfort. Comfort was generally described as closeness, often with language including “cuddles” (e.g., Michels, 2018, p. 8), “cozy” (e.g., Brundidge, 2015, p. 25), or “snuggled” (e.g., Rogers, 2016, p. 13) or was associated with warmth.

Unique breastfeeding situations depicted

Unique portrayals of breastfeeding appeared in this sample of children’s literature that specifically depicted breastfeeding and this content aligns with the topic of breastfeeding. A common narrative was a new baby or new sibling story (n = 18, 37%). Some books briefly mentioned a new baby, and others had significant storylines, alluded to in titles (e.g., Hello Baby!; Rockwell, 1999; Mommy Breastfeeds My Baby Brother; Repkin, 2009; My New Baby; Fuller, 2009).

Some books had illustrations or described children older than infancy breastfeeding with “when you were older you would climb all over me while nursing” (Brown, 2016, p. 9) or in I Like to Nurse subtitled a “Breastfed toddler story” (Brundidge, 2015, cover). Books also depicted formula feeding explicitly, for example, “formula from a bottle” (Danzig, 2009, p. 13), but also implied with images of bottles. In general, bottles were frequently depicted in the books. Simultaneously breastfeeding two different aged children was occasionally depicted. In Sharing Boo Boo, breastfeeding was described as “special just for us three” (Rogers, 2016, p. 10). Milk expression was described or illustrated (n = 9, 18%), with descriptions including “that is mommy’s breast pump” and an image of expression (Repkin, 2009, p. 18), and with “mummy pumped her milk for you” (Gabler, 2016, p. 10).

Weaning was another aspect of breastfeeding described in the books. Weaning varied from a brief mention to some books that had storylines of weaning. Weaning took various forms, with some books describing child-led weaning and others describing mother-led intentions to reduce or stop breastfeeding. Solid foods were often depicted in books, sometimes compared to breastfeeding with descriptions of infants breastfeeding and older children eating solid food. Other times books described how older children breastfed and also ate family foods. “I nursed after eating a slice of my chocolate birthday cake” (Brundidge, 2015, p. 13) described this combination, and child-led weaning is described as the main character in Loving Comfort “could feed himself, he didn’t need so much of Mama’s milk,” with an illustration of the child eating watermelon (Dillemuth, 2017, p. 10). Another depiction that frequently occurred was breastfeeding related to sleeping. While some books depicted breastfeeding at night, inferred by images of a night sky or dark room, other books more generally associated breastfeeding with sleep, for example, “warm milkies as I slowly fall asleep” (Craft, 2013, p. 24).

Educational depictions

The portrayal of breastfeeding often occurred in an educational manner with certain terms or visual portrayals. A predominant form of education occurred through choices of language. The terms used varied in that some were accurate in relation to adult language (e.g., breast), and others helpful in educating children about breastfeeding (e.g., mother’s milk). Some terms were child-centered (e.g., boo boo, milkies). Overwhelmingly these books use the term milk to refer to human milk, although less often other terms were used (e.g., mother’s milk, Mama’s milk). Only three books (6%) used the term breast milk. Infrequently the general term food, the Spanish Mama’s leche, (Mama’s milk) and the nicknames of boo boo and milkies were used. There was wide variation for the terms used to describe the behavior of breastfeeding and included (in order of occurrence; percentage total more than 100% because some books used multiple terms): feeding/fed/feed (n = 17, 35%), nursing/nurses (n = 16, 33%), breastfeed (n = 7, 14%), drink/drinking (n = 7, 14%), eat (n = 4, 8%), suck/sucked (n = 3, 6%), suckled (n = 2, 4%), boo boo (n = 1, 2%), nursies (n = 1, 2%), nummies (n = 1, 2%), dinner (n = 1, 2%), and nourishes (n = 1, 2%). Books also used different terms to refer to anatomy. Breast was the most common, although nipple, booby, and chest were sometimes used. Some books show illustrations of breasts. In The Mystery of the Breast, an illustration of newborn cuddling a breast is shown, and the image includes the nipple and areola (de Aboititz, 2011). Another form of education was the frequent comparisons of breastfeeding to how other mammals feed their young. Books compared human breastfeeding to how animals feed (n = 12, 24%). In one book, breastfeeding is contrasted to how monkeys, elephants, leopards, giraffes, llamas, pandas, zebras, cows, pigs, dogs, lambs, cats, and colts feed (Martin, 1995).

While there were overall positive depictions of breastfeeding in the sample, a few books depicted times when breastfeeding would be difficult when weaning or when an older child had to wait while a new baby breastfed. While these depictions showed problems, these all ended with issue resolution. In Mommy Breastfeeds My Baby Brother, an older child was upset about needing to be quiet while a new baby breastfeeds but is given a box of special toys to be played with at times when the baby breastfed (Repkin, 2009).

Discussion

In this sample of children’s books on the topic of breastfeeding, breastfeeding is portrayed positively. Scholars have called for wider messaging for breastfeeding traction for all stakeholders in breastfeeding success and have recognized the importance of normalizing breastfeeding through education (Azad et al., 2020). Children’s literature can be a way to provide education to young children about breastfeeding by providing terminology, familiarity with breastfeeding, and resources for education or information for parents.

Connecting breastfeeding to education can normalize breastfeeding or answer questions young children may have. Woodstein (2022) argued that English children’s books on breastfeeding often focus on educating an older sibling, an argument supported by the findings of the current study. While children’s books on the topic of new babies present formula feeding as the norm (Foss, 2017), this study finds that in children’s books specifically about breastfeeding, breastfeeding is positively portrayed and presented as an ordinary way to feed a baby.

In a study of baby books, Hutton et al. (2022) found baby books to be a feasible and helpful tool for providing healthcare guidance. The current research suggests children’s literature depicting breastfeeding is already being used as a way to provide information and resources to parents. Future collaborations and research can strategically improve this method of disseminating infant feeding research and resources.

Publications of children’s literature depicting breastfeeding were found to be increasing in recent years, and this may be due to public health promotions of breastfeeding (Office of the Surgeon General, 2011) and a reflection of general changes in breastfeeding culture. While Woodstein (2022) claimed breastfeeding is taboo in English-language children’s books, the findings of this study suggest this may be changing. Books containing content about human milk expression may reflect infant feeding practices today, with research suggesting the predominant style most breastfed infants are fed includes a combination of breastfeeding and expressed human milk (O’Sullivan et al., 2019). Recent publication increases may also be attributed to changes in publication processes. The most explicit breastfeeding books in Woodstein’s (2022) sample came predominately from one publisher, Pinter and Martin, a publisher that regularly publishes pro-breastfeeding works. In addition to pro-breastfeeding publishers, self-publishing aspects of the publishing industry have allowed for democratic and open written cultures with reductions in the publication gatekeeping that dominated in the past (Ramdarshan Bold, 2018). Julie Dillemuth is the author of Loving Comfort which has sold over 25,000 copies as a self-published book and has been translated into four additional languages (Dillemuth, n.d.). This suggests that while the publishing process for authors limits breastfeeding books to self-publishing, they can be popular with readers. Future research can explore the experience of publication for breastfeeding content for authors. While it is encouraging to see breastfeeding portrayed positively in these sampled books, this sample is small and likely from authors passionate about breastfeeding.

Current research on media portrayals of breastfeeding is limited and it is therefore difficult to place this study in context with other media forms that depict breastfeeding. This study may be useful for future research to extend sampling to include children’s books with any portrayals of breastfeeding, even those without breastfeeding or a new baby as a central aspect of the book. This could allow a more generalizable view of how breastfeeding is depicted in the books that children and families are likely to consume. In future studies, other social contexts, intended audiences (e.g., adolescents), and time periods of portrayals could be explored and compared. Additionally, future research could explore other media to provide a more detailed understanding of what children learn about breastfeeding through various media forms. While this study reveals an uncommon media depiction of breastfeeding, this may be due to underlying motivations for a positive portrayal of breastfeeding and because the authors and illustrators of this content may be intentional in their depictions. In addition, consumers of these books may actively select books on the topic of breastfeeding to provide a medium for discussion and learning (Woodstein, 2022).

This study has limitations in that it sampled American children’s literature with content related to breastfeeding, enough to appear on lists and searches related to breastfeeding. This study is limited to books that appear on lists and database searches. Books published by small or independent presses or that were self-published could have been missed in the data collection process. Due to a small sample size and focus on American books, implications from the current study should be restricted to the sampled books and not extended. In this study, there was also a possibility that researcher bias and positionality impacted the selection and analysis of books, and with only one researcher, there were no additional assessments of potential bias.

These findings have the potential to provide a means for distributing parent breastfeeding information and resources. While these children’s books about breastfeeding were identified in mainstream outlets (booksellers and libraries) it is not likely that they are consumed by most children (Foss, 2017; Woodstein, 2022). Access to these representations is limited to families intentionally seeking this media (Woodstein, 2022). One way to portray breastfeeding could be the inclusion of positive depictions of breastfeeding in books that are popular and mainstream, providing a wider audience with the kinds of portrayals found in the current study (Woodstein, 2022). A strengths-based approach can be useful in communicating with children about breastfeeding. Clinicians and practitioners can use the findings of the current study to promote these forms of children’s literature. Familiarity with breastfeeding through children’s literature may influence later breastfeeding as children become adults (Woodstein, 2022). Children’s literature with positive depictions of breastfeeding can be a way to provide children with the information they need to make informed decisions when they enter parenthood, regardless of whether they were breastfed as a child or not. Table 1 could be used as a recommended book list for families that are breastfeeding or intend to breastfeed.

References

Altshuler A (1995) Breastfeeding in children’s books: reflecting and shaping our values. J Hum Lact 11(4):293–305

Azad MB, Nickel NC, Bode L, Brockway M, Brown A, Chambers C, Goldhammer C, Hinde K, McGuire M, Munblit D, Patel AL, Pérez-Escamilla R, Rasmussen KM, Shenker N, Young BE, Zuccolo L (2020) Breastfeeding and the origins of health: interdisciplinary perspectives and priorities. Matern Child Nutr 17(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13109

Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA (2006) The bioecological model of human development. In: Damon W (Series ed) and Lerner RM (vol. ed) Handbook of child psychology: theoretical models of human development. Wiley, pp. 793–828

Brown K (2016) My mama’s milk (Basil E, Illus). Printed by author

Brundidge V (2015) I like to nurse (Atkinson C, Illus). Printed by author

Craft S (2013) Mama’s milkies (Berggren KM, Illus). Sweet P Press

Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2018) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage

Cutler L, Slicker G (2020) Picture book portrayals of the transition to kindergarten: Who is responsible. Early Childhood Educ J 48:793–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01040-w

Danzig D (2009) Babies don’t eat pizza (Tilley D, Illus). Dutton Children’s Books

de Aboititz V (2011) The mystery of the breast (Afra, Illus). Pinter & Martin, Ltd

De Visscher M (2020) Bye bye mommy’s milk (De Visscher M, Illus). Printed by author

Dillemuth J (2017) Loving comfort (Pratt V, Illus). Printed by author

Dillemuth J (n.d.) Julie Dillemuth: loving comfort. https://www.juliedillemuth.com/loving-comfort

Elder J (2019) My milk will go, our love will grow (Fein S, Illus). Heart Words Press

Foss KA (2017) “So you’re going to have a baby?”: Breastfeeding messages in parenting guides and children’s books. In: Breastfeeding and media: exploring conflicting discourses that threaten public health. Palgrave Macmillian

Foss KA, Blake K (2019) “It’s natural and healthy, but I don’t want to see it”: using entertainment-education to improve attitudes toward breastfeeding in public. Health Commun 34(9):919–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1440506

Fox P (2018) Babies nurse (Fox J, Illus). Platypus Media

Fuller R (2009) My new baby (Fuller R, Illus). Child’s Play (International) Ltd

Gabler J (2016) Mummy’s milk is made of love (Gabler J, Illus). Jacera Publishing

Graneheim UH, Lindgren B-M, Lundman B (2017) Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurse Educ Today 56:29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

Hackney M (2017) Mama’s leche (Ortiz M, Illus). Hohm Press

Huber PL, Gonzalez LC, Solózano DG (2020). Theorizing a critical race content analysis for children’s literature about people of color. Urban Educ. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085920963713

Hutton J (2015) Eat baby, healthy (Busch L, Illus). Blue Manatee Press

Hutton JS, Perazzo D, Boldt M, Leonard AC, Kelly E (2022) Safe sleep and reading guidance during prenatal care? Findings from a pilot trial using specially designed children’s books. J Perinatol 42:510–512. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01211-6

Klass P, Hutton JS, DeWitt TG (2020) Literacy as a distinct developmental domain in children. JAMA Pediatr 174(5):407–408. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0059

Labbok MH, Starling A (2012) Definitions of breastfeeding: call for the development and use of consistent definitions in research and peer-reviewed literature. Breastfeed Med 7(6):397–402. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2012.9975

Logan JA, Justice LM, Yumus M, Chaparro-Moreno LJ (2019) When children are not read to at home: the million word gap. J Dev Behav Pediatr 40(5):383–386. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000657

Martin C (1995) We like to nurse (Rainey SL, Illus). Hohm Press

Michels DL (2001) If my mom were a platypus (Barthelmes A, Illus). Platypus Media, LLC

Michels DL (2018) Cuddled and carried (Speiser M, Illus). Platypus Media, LLC

Moen C (1999) Breastmilk makes my tummy yummy. Midsummer Press

Neyland M (2017) A nursing love poem. Find My Balance Press

Neuendorf KA (2017) The content analysis guidebook, 2nd edn. SAGE

Office of the Surgeon General (2011) The Surgeon General’s call to action to support breastfeeding. United States Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov

O’Sullivan EJ, Geraghty SR, Cassano PA, Rasmussen KM (2019) Comparing alternative breast milk feeding questions to U.S. breastfeeding surveillance questions. Breastfeed Med 14(5):347–353. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2018.0256

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shameer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, … Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 10(89). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

Patterson MM (2019) Children’s literature as a vehicle for political socialization: an examination of best-selling picture books 2012–2017. J Genet Psychol 180(4-5):231–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.20191635077

Purnell-O’Neal M (2005) The wonders of mother’s milk (Simpson D, Illus). InterPress, Ltd

Ramdarshan Bold M (2018) The return of the social author: negotiating authority and influence on Wattpad. Convergence 24(2):117–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856516654459

Repkin M (2009) Mommy breastfeeds my baby brother (Moneysmith D, Illus). Istoria House LLC

Rockwell L (1999) Hello baby! Crown Publishers, Inc

Rogers A (2016) Sharing boo boo. Printed by author

Short KG (2018) What’s trending in children’s literature and why it matters. Language Arts 95(5):287–298. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44810091

Skrypuch MF (2013) The best gifts (MacKay E, Illus). Fitzhenry & Whiteside

Strouse GA, Nyhout A, Ganea PA (2018) The role of book features in young children’s transfer of information from picture books to real-world contexts. Front Psychol 9(50):1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00050

Woodstein BJ (2022) The portrayal of breastfeeding in literature. Anthem Press

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the librarians and staff at the University of Delaware Morris Library and the Harford County Public Library for their assistance in obtaining the books used in this study. I would also like to thank Josephine Bodt for her assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was determined to be not human subjects research by the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board, study number 1856406-1.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by the author.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bianca, K.P. Gifts, growing, and love: A qualitative analysis of children’s literature depicting breastfeeding. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 182 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01666-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01666-2