Abstract

In this work, the most recent Bautista-Manero-Puig (BMP) constitutive model-variant, i.e., the BMP+\(\_\tau _p\) rheological equation-of-state, is used as a theoretical approach to describe the thixo-viscoelastoplastic characteristics of human mucus-sputum in rheometric flows, focused on healthy, Cystic Fibrosis (CF) and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) affected samples, to determine its mechanical-to-biological response interplay. The BMP+\(\_\tau _p\) model reproduces quantitatively the mucus-sputum rheological behaviour in steady and unsteady shearing flows under conventional protocols. From such theoretical characterisation, predictions are presented for LAOS and uniaxial extension, evidencing that thixotropy impacts strongly on sputum rheological behaviour. On plasticity and thixotropy, an explicit inverse relationship between a fluidisation stress and the BMP+\(\_\tau _p\) thixotropic parameters is found and tested against independent measurements, giving: (i) quantitative agreement with medical reports; and (ii) evidence of a highly non-linear internal-structure rearrangement under LAOS. In the scarcely-treated mucus-sputum extensional deformations, BMP+\(\_\tau _p\) predictions provide a rheological signature as augmented strain-hardening extensional-viscosity peaks: an additional source of flow-resistance in expectoration processes, with mixed shear-to-extensional flows. This may serve as: (i) an advanced rheological basis for biomarker development to determine the patient state, (ii) a tool for the efficacy-of-treatment evaluation with potential application for newly-emerging illnesses, e.g., COVID-19, closely-related with CF in sputum consistency and symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mucus is a secretion that serves different functions for organs and glands in living systems, e.g., expelling of external micro-particles, hindering access of noxious agents to the epithelium and, in the respiratory tract, forming a selectively permeable layer for the diffusion and exchange of gases, and tissue lubrication1. Mucus composition consists of about 1% weight of salts or electrolytes, 0.5% - 1% of free proteins, 1% -5% mucin glycoproteins (mucins), and 97% water2,3,4. Also, bronchial mucus contains a significant proportion of lipids and, in pathological states, can also contain DNA and traces of other proteins coming from ruptured leukocytes3. Such composition confers non-Newtonian characteristics to mucus, particularly due to a somewhat complex protein-entanglement process5, i.e., (i) in general, protein concentration increases viscosity; (ii) mucin covalent networked bonds confer mucus its viscoelastic properties6,7; (iii) mucin clusters strengthened by non-mucin proteins generate a finite yield stress8,9; and (iv) the three-dimensional structure of the protein network correlates with time-dependent rheological properties, such as thixotropy10,11,12. We encourage our readers to see a broader explanation of mucin network characteristics, evolution and factors modifying its rheological nature in the work of Georgiades et al.13, Kavishvar & Ramachandran9, Wagner et al.14, and Esteban-Enjuto et al.15,16 Consequently, any affectation upon such network will lead to different complex rheological responses, which may be broadly classified as thixo-viscoelastoplastic (TVEP)8.

Mucus rheological characterisation may help to understand its role within the human body5,11,17,18,19,20. For example, respiratory mucociliary clearance relies on the rheological qualities of mucus, which modulate the transport processes between the cilia layers21. Furthermore, the rheological features of mucus may serve as biomarkers for respiratory disease diagnosis and monitoring18, even as predictors for clinical outcomes22,23,24,25, considering that respiratory diseases alter the usual concentration of proteins through antibody presence, strengthening the mucin network and changing the mucus flow properties25. However, sputum specimen collection (which is a mixture of saliva and mucus, coughed up from the respiratory tract) typically results in a non-invasive and straightforward procedure compared to obtaining mucus samples26. This is why most of research in the field of rheological characterisation is done upon sputum5,11,17,18,19. However, in some clinical settings, a more intensive approach may be necessary when patients have difficulty in expelling fluid from the upper respiratory tract26.

Like any ideal biomarker, those based on rheometric measurements must be reproducible, clinically relevant, sensitive, reliable, and easy to obtain27, aspects not yet fulfilled because of the lack of consensus on the experimental protocols and the pieces of information needed to understand and differentiate the complex rheological response of sputum. Nonetheless, rheological biomarkers present some advantages over conventional ones, such as being cost and time-efficient17, even standing as a non-invasive alternative to predict clinical symptoms22.

Two diseases whose study continues in the spotlight regarding their biomarker improvement are Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and COVID-1928,29. According to the World Health Organization30, one of the most common chronic respiratory diseases is COPD, which is the third leading cause of death worldwide. COPD symptoms include coughing, difficulty of breathing, wheezing, and tiredness, which leads to restricted airflow30. Besides, the lungs can get damaged or clogged with phlegm30. On the other hand, the COVID-19 disease has persisted as a worldwide health issue since the pandemic began and still calls for long term sustained prevention, controlling and management activities9,31. Severe Acute Respiratory Failure (SARS) is one of COVID-19 main complications. SARS is characterised by mucus hypersecretion and high viscosity sputum, resulting in chronic lung-clogging, inflammation and airway obstruction, accompanied with excessive bacterial growth and lack of proper oxygenation in the worst cases17,32. The flow properties of COVID-19 mucus are reported to be comparable in quality and intensity to those of Cystic Fibrosis (CF)9. Indeed, such intense growth of the sputum consistency is apparent in CF that its medical designation as mucoviscidosis reflects its critical condition of development19. Then, derived from the lack of recent studies reporting a thorough rheological characterisation of COVID-19 patients sputum - being, to the best of our knowledge, the work of Kratochvil et al.9 the only one dealing with such rather new respiratory illness-, one way to explore the rheological response of COVID-19 sputum is to study CF samples instead.

In Table 1, the most common biomarkers for COPD and CF are summarised, emphasizing on the type of biomarker, its characteristics and its utility in determining illness-state and treatment, if applicable. Mostly, they serve to determine severity and prognosis of respiratory disease33,34, to monitor the therapeutic response under specific treatments35, and to determine the occurrence of disease exacerbations36 (defined as a sustained worsening of symptoms, that has an acute onset and requires a change in the patients treatment37). Some of them are directly related to major symptoms, e.g. the Forced Expiratory Volume in one second (\(FEV_1\)), yet they are not exclusively used for either COPD or CF, but provide key information on the patient state, e.g., Clara cell protein (CC16)38.

To date, there are several studies seeking to link the macroscopic flow properties of mucus and sputum with its physicochemical characteristics, as a way to develop biomarkers for COPD an CF.

Among those of experimental character in the field of rheological characterisation, the early work of Dawson et al.5 attempted to describe human sputum as a viscoelastic solid, with a characteristic gel-like behaviour at small deformation amplitudes, where the storage modulus (\(G'\)) rises monotonically, whilst the loss modulus (\(G''\)) remained constant over the frequency-range analysed. Under larger deformations, their sputum samples displayed thinning trends in viscosity and elastic modulus.

In this same context, Nielsen et al.11 provided evidence of a more complex rheological response of sputum, for which significantly long times to attain steady-state viscosity measurements are reported, marking the influence of thixotropy in their sputum samples. Here, similarly to Dawson et al.5, a significantly-increased consistency of CF sputum has been systematically associated with the presence of DNA and other proteins originating from ruptured-leukocyte remains - in excess when an infection is active in the human body.

More recently, Tomaiuolo et al.17 concluded that the \(G'\) magnitude is correlated to the \(FEV_1\) index and to specific bacterial colonies in CF-affected sputum samples. Thus, such rheometric \(G'\)-measurement helped to identify the disease severity, which was essentially related -according to these authors- to the presence of high molecular-weight components of sputum, which rendered their samples as thixo-viscoelastoplastic materials.

Hill et al.34 proposed the mucus solid-concentration as a potential biomarker (considering solids as mucin and non-mucin proteins, salts, lipids, and cellular debris40). These authors were able to measure the differences between healthy, COPD and CF samples, finding a critical solid concentration at which a transition from liquid to solid-like response occurs, recorded using the calculated \(G'\) and \(G''\) moduli magnitudes.

Nettle et al.22 carried out Small Amplitude Oscillatory Shear (SAOS) and creep-recovery tests in an attempt to correlate the rheological properties of sputum with clinical data on the severity of symptoms in COPD patients. Their findings suggested that the elastic modulus \(G'\) could be a more suitable measurement of mucus physical properties than the shear viscosity. These authors fitted their experimental elastic modulus data using the Power-Law constitutive relationship. Here, the Power-Law index was correlated with the ratio of \(FEV_1\) to the Forced Vital Capacity of the lungs (FVC), namely \(FEV_1/FVC\), which is a clinical measurement of COPD severity and a lung damage indicator17,22. Lower \(FEV_1/FVC\), indicating the worst exacerbations, corresponded to smaller Power-Law indexes (all \(<1\)), which is interpreted as a relatively more pronounced shear-thinning response.

Patarin et al.19 characterised sputum samples from healthy individuals, asthma, COPD and CF patients in linear and non-linear viscoelastic regimes. They demonstrated how the sputum critical stress (\(\sigma _c\)), defined from the intersection between \(G'\) and \(G''\) in an amplitude sweep, can be used to diagnose respiratory illnesses such as COPD and CF, since the ciliary transport efficiency declines with the augmentation of \(\sigma _c\). In this respect, these authors provided representative measures of the elastic-modulus increase with the illness worsening, from which one can extract an increase of some 10-20 times the COPD-CF samples over the healthy references. For the plastic response measured through the critical stress, these authors reported distinct responses between COPD and CF-affected samples, and those of healthy individuals, for which an increase of some 5-10 units of stress is witnessed for the diseased samples. Therefore, their work highlights the importance of considering the dynamic properties of sputum as viable biomarkers for chronic bronchial diseases. In line with the work of Patarin et al.19, Ghanem et al.41 tested samples from healthy and CF patients with some illness degree and under a mucolytic spray treatment in simple shear flow, to evaluate the correlation between an apparent yield-stress and the illness development, for which the plastic properties of their samples turned out to be the best candidate for a biomarker development to monitor the mucolytic performance.

Jory et al.20 used micro and macrorheology to quantify the viscoelastic properties of human bronchial epithelium mucus. Healthy and COPD samples were tested to obtain steady shear, frequency and deformation sweep curves. After fitting the data with the Power-Law rheological equation-of-state, they concluded that mucus behaves like a shear-thinning viscoelastic material at the macro-scale, and as a viscous liquid at the micro-scale. They explained this difference between macro and micro rheological responses by classifying mucus internal structure as an elastic filament network embedded in a soft gel, rendering sputum as a thixo-viscoelastic gel with yield stress that follows a Power-Law dependence under extreme shear-thinning regimes characterised by negative Power-Law indexes.

Kratochvil et al.9 studied the physical, chemical and immunological properties of sputum infected with severe SARS-CoV-2. Here, these authors stated a direct relationship between the CF and COVID-19 sputum consistency. They identified a increased amount of DNA and hyaluronan (HA) in ill-secretion samples compared to healthy ones, which was reduced by an enzymatic treatment with HAdase and deoxyribonuclease. A comparison between the pre-treatment and post-treatment elastic modulus (\(\Delta G_{Saline}-\Delta G_{Enzyme}\)) revealed that this difference in consistency was almost null for healthy secretions, and different to zero for COVID-19-affected samples.

Despite of all these efforts, no agreement is found to date about what should be a suitable experimental protocol to obtain or test mucus and sputum samples15. Neither there is a standardised way to present nor interpret the rheometric measurements, partly given that flow properties vary form one patient to another regardless of their health condition1, and that obtaining samples is challenging enough10. Additionally, most of experimental rheometry on mucus and sputum characterisation focus on shearing flow, since this kind of deformation is hypothesised to dominate mucus propulsion in airways20 during the mucociliary clearance process42,43. However, uniaxial extensional deformations, which play a relevant role in the mucus and sputum expectoration process - recall spasms and airway contraction-expansion in closure and opening processes18,44,45- remain unexplored, as well as their correlation with other material functions and complex flows occurring in the respiratory system.

In terms of theoretical-rheological characterisation and computations, López-Aguilar et al.44 and Tabatabaei et al.18 used early model-variants of the Bautista-Manero-Puig family-of-fluids, i.e., the NM\(\_\tau _p\) equation46, and the Pom-Pom theoretical framework, to describe human COPD sputum and bile in biliary conducts with obstructions, and to simulate the formation of filaments and the biofluid response in obstructed conduits within the human body. Through such simulations it was possible to estimate the extensional viscosity evolution, and its influence in relevant physiological functions.

Erken et al.47 employed a variant of the Saramito model, namely the Saramito-Herschel-Bulkley model, to fit the oscillatory shear experimental measurements reported by Patarin et al.19. The Saramito model is a combination of the Oldroyd-B and Bingham constitutive equations, whilst the Saramito-HB model is the corresponding Herschel-Bulkley variation48,49. The Saramito constitutive equation is characterised for physically-consistent predictions for \(G'\) in oscillatory-shear strain-amplitude sweeps, but not for \(G''\). Saramito et al.48,49 attempted to solve this problem by considering a kinematic-hardening mechanism. By comparison of the fitting parameters (elastic modulus, yield stress, Power-Law index and consistency parameter), Erken et al.47 were able to set a clear difference between healthy, COPD, asthma and CF samples. The yield stress and elastic modulus of COPD and CF samples were ten times higher than those of healthy individuals, whilst \(G'\) magnitude of CF samples doubled the one from COPD patients. Erken et al.47 also simulated the airway closure due to liquid plug formation; they concluded that this phenomenon is promoted and dominated by the mucus viscoelastic features.

Sedaghat et al.43 have successfully approached the mucocilary clearance process by numerical simulation, using a multimode Giesekus equation. Such constitutive model was validated by Vasquez et al.50 in steady and oscillatory shear flow, for a healthy mucus sample. However, this model does not account for time-dependent material responses, such as thixotropy, which appears clearly manifested in experiments11. Nevertheless, the results of Sedaghat et al.43 prove that an Oldroyd-B-type multimode constitutive equation could be scalable to numerical simulations of physiological flows.

Applications - Monitoring clinical outcomes of targeted treatments for chronic pulmonary diseases. In general, the increase of viscosity and elastic modulus under chronic pulmonary diseases, which is often referred to as a change in consistency, is the distinctive trait between healthy and ill-mucus or sputum samples9,51. This explains to some extent the hindered mucus expectoration process, given that a stiffer consistency of mucus promotes chronic lung-airway obstruction, inflammation and infection17. Most basic treatments deal with these symptoms via the administration of active principles that lower the mucus viscosity or reduce its yield-stress11. Hence, a thorough rheological characterisation of sputum in healthy and relatively-advanced states of pulmonary illnesses could serve as a monitoring tool to determine the effectiveness of mucolytic treatments.

Other applications of such rheological characterisation are: (i) the prospective development cheap and easy-to-use devices for clinical practise in hospitals17, (ii) monitoring the effects of pharmacological treatments, not only in humans41 but also in the livestock and poultry industries52, (iii) the study of drug delivery and diffusion of active principles5,17, (iv) the study of illnesses for which the rheological characterisation of biofluids is relevant for diagnosis and treatment, such as periprosthetic joint infection and synovial fluid23, eye edema, cataracts and vitreous humour53, the reproductive system and vaginal fluids54, among many others.

Hence, as it is evident in the richness of the afore-mentioned experimental and theoretical proposals alongside their applications, from a fundamental point-of-view, a deep study of the rheological response of mucus-sputum can contribute to shed light onto the changes in their micro-structure and their influence in the mucus-sputum macroscopic mechanical response and its effects in airway clearance11.

Until now, we identify the following shortcomings for the rheological study of mucus an in the context of COPD and CF diseases: (1) the lack of a standardised protocol for interpreting rheometric measures; (2) the constitutive equations used to model the rheological phenomena of mucus are not able to capture all the range of mucus non-Newtonian responses (e.g. Power Law20,22, Saramito47, Quemada12,21), or are overly complex, compromising the capacity to using them in numerical simulations of physiological processes, such as the mucocilary clearance43,50,55; and (3) studies are constrained to rheometric shear flows. In this work, we propose a way to cope with these issues. Further than focusing on the elasto-plastic behaviour, we suggest that mucus thixotropic properties, that had been let aside in previous proposals5,19,20,22, can provide valuable information to differentiate between healthy and ill samples. For this purpose, we use the most recent Bautista-Manero-Puig (BMP) constitutive equation model-variant, i.e., the BMP+\(\_\tau _p\) rheological equation-of-state56,57,58, to describe the thixo-viscoelastoplastic response of healthy, COPD and CF mucus samples in rheometric flows, ranging from steady and transient shear, and oscillatory deformations. We contrast the model description against experimental data reported from literature5,11,19,20. With such capability of mathematical modelling prediction, we provide a consistent standardised framework to interpret the resulting flow properties in terms of the thixotropic and viscoelastic parameters of the BMP+\(\_\tau _p\), including a measure of a critical stress for sample fluidisation, that identify starkly healthy-to-ill conditions of COPD and CF human mucus-sputum samples. From here, we provide numerical predictions for uniaxial extensional flow in the form of extensional viscosity trends in steady and transient tests, for which the BMP+\(\_\tau _p\) thixotropic parameters provide a signature of CF illness worsening.

Methods

To understand the mechanical response of any fluid through its rheological characterisation, it is essential to identify its non-Newtonian features to choose a suitable theoretical framework, which shall include a constitutive equation relevant to the desired applications, capable of predicting the rheological features of the material59,60. In this section, we describe our characterisation methodology, which consists of three basic steps: (i) the selection of experimental data and its classification according to the rheological behaviour of samples displayed in their flow-curves, followed by (ii) the choice of a theoretical framework and its corresponding constitutive equation, potentially capable of reproducing the rheological features of the material; and (iii) the mathematical modelling of relevant rheometric tests.

Experimental data sets

Complex fluids such as human mucus and sputum show a wide range of rheological features that are not always observed unless more than one rheometric test is performed. In general, through steady shear flow tests, it is possible to identify shear thinning or thickening, and yield stress. Small and Large Amplitude Oscillatory Shear (SAOS and LAOS, respectively) data, such as frequency and amplitude sweeps, provide crucial information to classify viscoelastic and other non-linear responses61,62,63,64. Extensional flows can provide rheological fingerprints that are not present in shearing deformations, like, e.g., the Trouton ratio (Tr), which is a comparison between the fluid response to a strong deformation (in the sense of having a null vorticity tensor associated to the deformation) such as uniaxial extension, and its response to a shearing flow. Under uniaxial extension, a value of \(Tr>3\) indicates a viscoelastic strain-hardening response, that also can be anticipated from the increase in extensional viscosity from the first Newtonian plateau60. This is a manifestation of the additional resistance to flow biofluids might display in complex-flow configurations (e.g., in the airways), originating from its extensional rheological properties.18 Transient tests, like thixotropic cycles, as well as step-up or step-down in shear rate or stress, and hysteresis loops, assess thixotropy and other time-dependent phenomena. For the characterisation of complex fluids, the more rheometric information available, the more complete the fluid description will be attained.

In the case of rheological characterisation of human sputum, several authors have dealt with this challenging experimental task5,9,11,17,19,20,22,34,47,50. As a first step in this procedure, we have selected a subset of experimental data reporting thoroughly the rheological response of human sputum under healthy and in some illness conditions, such as CF and COPD5,11,17,19,20, which are listed in Table 2. This selection is based on the completeness of experimental protocols employed by the authors of these studies, and the availability of sufficient cases for comparison between healthy references, CF or COPD samples.

Here, the notion of completeness and sufficiency is related to the mathematical modelling of rheological responses of such complex biofluids, where choosing an appropriate or sufficient set of rheometric measurements is an important task to complete, since the amount of data sets and their quality will influence centrally the effectiveness of the fitting procedure and the corresponding rheological explanation that may be withdrawn. Depending on the complexity of the constitutive model, and particularly on the number of parameters in its formulation, one can set a minimum number of rheological signals to work with consistently. In terms of a thixo-viscoelastoplastic material such as sputum and mucus, rheological data sets providing information on the shear thinning characteristics of the biofluid plus its viscous Newtonian plateaux, a viscoelastic signal for determining the relaxation time, and a couple of signals of non-linear nature to find estimates for the thixotropic and plastic features would be enough to start with. If, on top of that, we had information on extensional response of these biofluids, we would be in an ideal scenario. Given that this is not the case, we propose our methodology and results as a starting point for a consistent rheological characterisation of these complex biofluids, with the potential to be expanded into a more detailed description provided that enough data sets on different composition, illness type and other relevant factors are available.

In view of the characteristics of the experimental protocols found in literature, which are based on shearing flow tests5,11,17,19,20, and that to the best of our knowledge, the only extensional rheometric measurements available in the literature are performed upon mucin solutions and saliva, which are the simplest yet the closest systems to mucus and sputum65,66, our results in the modelling of extensional flow are predictive in nature (see the Results and Discussion section). Then, their validity relies only on the hypothesis that if we can accurately describe the shearing flow phenomenology, through informed fittings under linear and non-linear regimes, it is likely that our predictions in other deformations, such as uniaxial extension, may offer insights into the response of mucus and sputum under such deformations. Moreover, it is important to provide predictive information on the extensional response of these biofluids, since its key role is well known in lung and airway blockage.18,47,67,68

Returning to the experimental data sets, in order to summarise and classify our selection to be considered in this work, the type of samples and experimental protocols reported in the literature are listed in Tables 3 and 4. We prioritised studies comprising material functions for steady flows, oscillatory shear and transient tests. Table 3 serves to classify the sample type, either Healthy, CF or COPD affected, according to the rheological property explored. Here, the more common material properties studied are steady simple-shear apparent viscosity \(\eta\) against \(\dot{\gamma }\), and storage \(G'\) and loss \(G''\) moduli response under oscillatory shear, observing frequency \(\omega\) and deformation-amplitude \(\gamma\) variations. The more advanced and detailed inspection of sputum samples are performed by Jory et al.20, Nielsen et al.11, Dawson et al.5, and Tomaiuolo et al.17, under Lissajous curves obtained under LAOS protocols, transient viscosity, compliance and deformation responses to uncover the thixotropic features of human sputum. In literature, the general practice is to report only representative experimental results. Therefore, the mathematical modelling presented in this paper is based on that average data.

In addition, Table 4 provides a brief description of the rheological measurements, the flow characteristics reported by those authors and its relationship with their clinical use, where applicable. This summary may serve to condensate and identify the main rheological characteristics of human sputum. From this data collection, we analysed the experimental results (see Tables 3 and 4), from which we start by making reference to specific pieces of information in the afore-mentioned references to signal and identify key rheological responses:

-

(i)

Apparent viscosity response - In Fig. 1 of the work of Jory et al.20, as well as in Fig. 7 in Nielsen et al.11, in Fig. 1c in Dawson et al.5, and in Fig. 1a on Tomaiuolo et al.17, a marked shear-thinning response of mucus is revealed through a flow curve (viscosity versus shear-rate) for which the viscosity drops with shear-rate increase some five-to-seven orders-of-magnitude. Moreover, such starkly marked shear-thinning trend follows a Power-Law-like trend with negative indexes of around -0.85 units, as reported by Jory et al.20. These two characteristics of mucus and sputum rheological response have already been reported for the flow of wormlike micellar solutions, where such negative Power-law indexes are signatures of the onset of a shear-banding instability. Shear banding is a flow transition characterised by a spontaneous segregation of the fluid into bands of different material properties, e.g., viscosity or elastic moduli, and that has been described and systematically predicted with the BMP family-of-fluids58.

-

(ii)

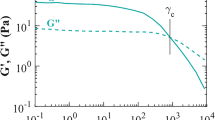

Storage \(G'\) and loss \(G''\) moduli and yield stress - Frequency sweeps under SAOS from Fig. 2 in Jory et al.20, Fig. 1a in Dawson et al.5, and Fig. 3 in Tomaiuolo et al.17, unveil a viscoelastic response of soft-gel-like systems and yielding fluids under oscillatory deformation69, as \(G'>G''\) for low-to-moderate values of frequency (\(\omega\)) and strain (\(\gamma\)). The supplementary material given by Jory et al.20 and Fig. 1 in Patarin et al.19 show that mucus response to oscillatory shear (\(G'\) and \(G''\) versus strain) fits the classification of viscoelastic strain-thinning, according to the general convention: decreasing \(G'\) and \(G''\) at high strain values, without overshoots for none of the moduli62,70. Also, following one of the methods to determine the existence of a yield stress in soft-gel-like systems, i.e. the point at which \(G' = G''\)71, mucus samples manifest a measure of its plasticity, the so-called critical stress (\(\sigma _c\)).

-

(iii)

Thixotropy - Evidence of mucus thixotropic behaviour is found in Fig. 4 and 5 in Nielsen et al.11, and Fig. 1c in Tomaiuolo et al.17, for which CF-sample flow curves display hysteresis (a common manifestation of thixotropy72,73), and the transient response in start-up flow test reflect the effect that the history-of-deformation has on the microstructure11.

Hence, in culmination of the first step of our proposed rheological-characterisation procedure, this number of distinct rheological features permits to qualify human sputum under healthy, and CF or COPD ill-conditions, as a thixo-viscoelastoplastic material.

The second step in our characterisation procedure is to choose a suitable theoretical framework and its relevant constitutive equation, capable of describing the basic rheological features of the material at hand. In the present case, given that human sputum displays time-dependent viscoelastic features with marked yield-stress characteristics, the BMP constitutive modelling approach56,57,58 arises as a feasible choice. The BMP family-of-fluids appears as a well-established option providing thixo-viscoelastoplastic responses, which have been tested in many different materials, such as thixo-viscoelastic wormlike micellar surfactant solutions46,74, biofluids18, aluminium alloys75, among others. In this work, we use the most recent BMP constitutive equation model-variant: the BMP+\(\_\tau _p\) rheological equation-of-state56,57,58.

Once chosen the theoretical framework to work with, the third step in our characterisation protocol comes with the mathematical modelling of the relevant rheometric tests to characterise the material. The results of such mathematical modelling are provided in the next section. Before presenting the experimental-to-theoretical comparison of sputum rheology and the corresponding predictions, we describe the BMP+\(\_\tau _p\) model in detail, alongside its qualities and advantages compared against other thixo-viscoelastoplastic rheological models in the literature, and the parameter-fitting procedure followed in this work.

The Bautista-Manero-Puig constitutive equation

The Bautista-Manero-Puig (BMP) rheological equation-of-state was proposed originally for describing the behaviour of worm-like micellar solutions74,76. The most recent version of this model, the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) rheological equation-of-state56,57,58, considers some generalisations for the application of this model in complex flows, retaining its capabilities in terms of the prediction of shear-thinning, extension hardening and softening, highly non-linear viscoelasticity, and flow segregation in the form of apparent yield-stress and banding. Such generalisation is achieved via the inclusion of viscoelasticity into the material-structure time-evolution dynamics, and using the magnitude of the energy dissipated by the solute in motion to drive non-linear rheological responses - for further details, refer to López-Aguilar et al.56,57,58.

The mathematical formulation of the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model consists of stress (\(\varvec{\tau }\)) contributions expressed in an additive fashion, conceptualising the behaviour of a dissolution under an Elastic-Viscous Stress-Splitting approach in a generalised Oldroyd-B-like differential formulation, composed by an upper-convected Maxwell component for the solute, symbolised as \(\varvec{\tau }_p\), and a Newtonian contribution for the solvent, identified as \(\varvec{\tau }_s\), viz.:

where \(\overset{\nabla }{\varvec{\tau }_p} = \frac{d\varvec{\tau }_p}{dt} + \textbf{v}\cdot \nabla \varvec{\tau }_p - \nabla \textbf{v}^{T}\cdot \varvec{\tau }_p - \varvec{\tau }\cdot \nabla \textbf{v}\) defines the upper-convected time-derivative of \(\varvec{\tau }_p\). The viscoelastic relaxation-time \(\lambda _1\) modulates the influence of this upper-convected time derivative and, hence, the strength of viscoelasticity of the material. The diffusive mechanisms on both solute and solvent stress components are modulated by \(\eta _{p_0}\) and \(\eta _s\), respectively, which, correspondingly, represent the level of the solute first-Newtonian plateau and the solvent viscosity. Here, the gradient operator \(\nabla\) applies over the spatial coordinates and the superscript \(\phantom{0}^T\) stands for a transpose operation over the velocity-gradient tensor \(\nabla \varvec{v}\). The rate-of-deformation tensor \(\varvec{D}=\frac{1}{2} (\nabla \varvec{v} + \nabla \varvec{v}^T\)) collects the isotropic rates of deformation an element of fluid can experience in a three-dimensional space.

The solute stress equation (Eq.(1)) is coupled with a kinetic equation that describes the material internal-structure temporal evolution via a dimensionless fluidity measure (f), given by:

Here, f is defined as \(f = \frac{\eta _{p_0}}{\eta _{p}}\), where \(\eta _{p}\) is the non-Newtonian viscosity of the solute; the total viscosity of the dissolution \(\eta\) is defined as \(\eta = \eta _{p} + \eta _s\). The structure evolution equation describes the thixotropic properties of the material through a characteristic time of structure-construction \(\lambda _s\), and the inverse of the structure-destruction stress k. These two mechanisms of structure construction and destruction obey a dynamical equilibrium in which the energy dissipated by the solute in motion drives the structure evolution in-between two extreme values: (i) \(\eta _{p_0}+\eta _{s}\) for fully-structured materials, and (ii) \((\eta _{\infty }+\delta )+\eta _{s}\) for fully-unstructured fluid responses, where \(\eta _{\infty }\) is the non-Newtonian high shear-rate viscosity.

For flow-segregation response predictions in this context, the destruction coefficient k should take a linear functionality with the applied shear-rate of the form \(k = k_0 + \nu \dot{\gamma }\);58 here, \(\nu\) is the shear-banding intensity-parameter. The quantities \(\lambda _s\) and \(k_0\) implicitly depend on the fluid microstructure construction-destruction mechanisms74. Additionally, flow segregation in the form of yield-stress is obtained under extreme solute concentrations (translated as well into strong shear-thinning responses, or, low solvent-fraction \(\beta\)-conditions, i.e. \(\beta = \frac{\eta _s}{\eta _{p_0}+\eta _s}<<1\). The viscoelastic contributions are significant if \(\lambda _s<<\lambda _1\).

The multimode version of the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) equations follows as:

where \(\varvec{\tau }_p\) and \(\varvec{\tau }_s\) obey Eq.(1) and n represents the number of stress modes considered.

As such, the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) constitutive equation arises as a suitable theoretical framework to reproduce the mucus and sputum rheological responses based on the qualities of its precursor, the BMP model, as it can describe non-linear rheological responses in transient loops and small amplitude oscillatory shear (SAOS)76. Furthermore, a multi-mode version of the BMP equation successfully modelled the rheological behaviour of blood with various cholesterol levels77. Even later modifications of the BMP model reproduce qualitatively the response of thixotropic and viscoelastoplastic fluids in complex flows56,57,58.

One of the main advantages of the BMP constitutive model is its simplicity: alongside the several rheological responses that it can describe, all its parameters have a specific physical-rheological meaning. Moreover, the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) measure of yield stress may be described as apparent, since its definition depends on the relative difference between \(\eta _{p_0}\) and \(\eta _\infty\). Notably, it is possible to define a critical stress \(\tau _c =\sqrt{\frac{\eta _\infty }{\lambda _s k_0}}\), which is analogue to the yield-stress in the Bingham model. \(\tau _c\) can be identified in a \(\tau _{12}\) vs \(\dot{\gamma }\) log-log plot, as the plateau in shear stress74.

Fitting procedure

There are three fundamental aspects of the mathematical modelling of rheological responses that lead to exploit the full describing ability of a constitutive equation. Firstly, one should know the significance of constitutive-model parameters and the physical meaning associated to their combinations. Secondly, one should determine the scope of rheological responses that can be predicted with the constitutive model chosen, by performing a parameter-sensitivity analysis. Finally, one should identify the role the parameters play under specific rheometric test aimed to determine the relevant material properties or generalised flow conditions. The meaning, sensitivity, and the role the parameters play on the predictions depend on the constitutive model characteristics and the kinematics imposed by the flow itself. Besides, understanding the theoretical model in the context of a multi-mode approach is key for analysing data coming from biological samples, since their characteristics are influenced by averaged effects coming from the inhomogeneous biofluid features.

As exposed in the previous section, in the specific case of our BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model, its mathematical statement is engineered through two solute viscosity levels determined at vanishing and large deformation rates (\(\eta _{p_0}\) and \(\eta _{\infty }\) respectively), and the viscosity of the solvent contribution (\(\eta _s\)), which collapse in a single solvent-fraction parameter \(\beta = \frac{\eta _s}{\eta _{p_0}+\eta _s}\); one parameter related to viscoelasticity (defined either as either \(\lambda _1\) or \(G_0\)), two parameters related to internal-structure re-arrangement and thixotropy (\(\lambda _s\) and \(k_0\)), and a parameter for shear banding (\(\nu\)). One can define a parameter to estimate the apparent yield-stress features of the sample, which linked to the calculated critical stress of fluidisation (\(\tau _c\)) and is a combination of the thixotropic and viscous parameters. Hence, for this case, the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model has seven parameters to be determined.

Then, under transient homogeneous deformations, the mathematical nature of this problem arises as a system of ordinary differential equations for shear and normal stresses, fluidity, and moduli, with six unknowns per mode, for which a numerical algorithm based on a fourth-order Runge-Kutta method was used, and a Romberg integration scheme to calculate material functions for oscillatory shear tests.

In this kind of mathematical modelling exercises, in which the determination of model parameters associated with material functions is performed, care must be taken in the balance between the number of parameters to be determined (associated with the constitutive model complexity), and the quantity, quality, and type of experimental data-sets. Ideally, the number of parameters to be determined and the number of experimental data-sets should be equal, rendering a null number of degrees-of-freedom; if this condition is met, one can qualify the case as a closed system. In addition, experimental data sets need to come from appropriate protocols directed to identify specific rheological responses. An additional source of information on the magnitude of parameters may come from reports elsewhere; nevertheless, although such sources of informed estimations are convenient, sometimes they are scarce or not generally applicable, such as in the case of biofluids1,8,15,16,78. Complementarily, through a parameter-sensitivity analysis, it is possible to estimate the influence and values for the remaining unknown parameters. Further details on how the parameter combination and variation impact on the type of BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) responses are provided in the Appendix.

This generalised procedure applied to the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model crystallises over the next steps:

-

(i)

Steady-state viscosity against shear-rate flow curves - From the experimental steady-state apparent viscosity response, one can extract the value of \(\eta _{p_0}\), \(\eta _\infty\), and the product of the thixotropic parameters \(\lambda _s\cdot k_0\), which modulates the shear-thinning slope in the apparent viscosity response, and its inverse value provides the energy dissipation rate per unit volume necessary to breakdown the fluid internal structure. As it will be explained further in the following section, such an energy-dissipation measure correlates with the thixo-viscoelastoplastic rheological response of healthy and ill-conditioned human mucus-sputum. The product \(\lambda _s\cdot k_0\), as well as \(\eta _{p_0}\), \(\eta _\infty\) values are kept fixed for the following fitting steps in this procedure, leaving only three unknowns per mode.

-

(ii)

Small Amplitude Oscillatory Shear flow - These oscillatory shear results are used to find the number of stress-modes n needed to characterise the samples and the corresponding values of \(\lambda _1\), related to viscoelastic features. Likewise, \(\lambda _1\) spectra are kept fixed for the following steps, leaving only two parameters to determine per mode.

-

(iii)

Transient start-up shearing flows, Lissajous curves and thixotropic-loops - Time-dependent tests in the form of start-up flows, Lissajous curves and thixotropic loops serve to determine the individual values of \(\lambda _s\) and \(k_0\). Particularly, if there are both transient data and Lissajous curves available, it is possible to identify if a shear banding parameter is needed. This leaves only one parameter to be determined per mode.

-

(iv)

Viscosity of the Newtonian solvent - Based on its physical meaning, we set \(\eta _s\) as the viscosity of water (the actual solvent of mucus2,3), which amounts 0.001 Pa s.

-

(v)

Closed systems - The only closed system we are working with is CF-311. Closure on the rest of systems is achieved by estimating parameter values observing trends in the closed systems.

Since one of our goals is to determine the generalised mechanical behaviour of mucus-sputum by using a TVEP theoretical approach in the characterisation of mucus and sputum, we considered finding the value of parameters through educated guesses and a trial-and-error procedure, supported by the parameter sensitivity analysis, to be acceptable enough in this instalment. The accuracy of the procedure is quantified through the \(R^2\)-coefficients reported. Notably, our results are quantitatively consistent with experimental values reported in the literature on typical measures used clinically1,8,15,16,20,78, such as the fluidisation stress in the determination of a patient illness state, as we will discuss in the Results and Discussion section.

A final consideration in this procedure is relevant in this case, in which complex biological fluids are studied: a case-by-case analysis should be taken into account given that every study in Table 4 follows a different protocol for the collection and handling of samples. Additionally, as any thixotropic fluid, human sputum is sensitive to the deformation history11,17. Hence, the results presented in the Results and Discussion section are analysed by case-study following the organisation in Table 2.

Results and discussion

In this section, we show and discuss the results of the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) experimental data fitting obtained under varied shear-deformation-based tests, and the predictions of this constitutive equation in uniaxial extensional deformations. These fittings are performed over the rheological characterisation protocols available in the literature, as summarized in Table 3. It is worthy to state that the analysis of these results is primarily addressed on the parameters of the first stress-mode, since this mode dominates the rheological responses in the linear and incipient non-linear regime, in which the physiological flow conditions within the airways occur, i.e., creeping flow conditions42. Additionally, parameters related to the first mode strongly influence the overall behaviour at medium and high deformation rates. Then, in our analysis we will be referring to the parameters of the first mode of stress response, unless otherwise stated.

In addition and contrast to previous studies5,11,17,19,20,47, once a proper rheological characterisation is achieved under shearing deformations, predictions are provided on the response of each mucus-sputum case under uniaxial extensional flow, for which steady extensional viscosity \(\eta _E\) and transient material functions (tensile growth coefficient, \(\eta _E^+\)) are calculated. The extensional response of mucus and sputum is relevant to the expectoration process, in which extensional deformations prevail18.

Following Table 2, result description is categorised according to each data-set with two main objectives: (i) to describe each data-set on its own context in terms of group-of-individuals tested and particular rheometric techniques used, to extract the specific rheological response of each data-set; (ii) then, with the characterisation of each sample, to find a generalised description of the rheological response of mucus and sputum in healthy and ill conditions.

Contrasting healthy and COPD samples through rheological characterisation (Healthy-1 and COPD-1 from Jory et al.20)

Figure 1 provides the comparison between experimental data of steady simple shear flow reported by Jory et al.20 and the fitting obtained under the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model. Note that experimental data is tagged according to the classification in Table 2. The apparent shear viscosity (\(\eta\)) against shear rate (\(\dot{\gamma }\)) plots in Fig. 1 show quantitative agreement between the model predictions and experimental data (\(R^2 \ge 0.97\)). Both healthy and COPD-affected mucus samples display a plastic response through an apparent yield stress, i.e., a drastic drop in viscosity from the first to the second Newtonian plateau79. From Table 5, one can gather that the level of the first Newtonian plateau (\(\sum \eta _{p_0}^i+\eta _s\)) for sample COPD-1 is almost three-times larger than that for Healthy-1, whilst the level of the second Newtonian plateau measured from the solute contribution (\(\sum \eta _{\infty }^i+\eta _s\)) in the case of COPD-1, double the one for sample Healthy-1. This phenomenon may be explained physiologically through the difference in solid concentration, for which COPD-samples generally present an augmented quantity of DNA and other proteins coming from protective mechanisms.

With respect to the strength of the shear-thinning characteristics of both samples, one notes that they share the same order-of-magnitude drop in viscosity (a drop of some four-to-five decades in viscosity), and even a similar shear-thinning slope; within the BMP theoretical framework at hand, the value of the \(\lambda _s \cdot k_0\) product determines such a rheological feature. The \(\lambda _s \cdot k_0\) parameter-product has units of inverse of rate of energy-dissipation per unit volume; hence, \((\frac{1}{\lambda _s \cdot k_0})\) represents the characteristic energy dissipation rate per unit volume required to breakdown the fluid structure. Here, from Table 5, one notes that \(\lambda _s \cdot k_0\) product across samples appears under the same order-of-magnitude, but smaller in the case of sample COPD-1; in general, the reduction of \(\lambda _s k_0\) in the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) renders a weaker shear-thinning response, which correlates with the augmentation of viscosity for sample COPD-1. In this context, the proposed expression for the critical stress is \(\tau _c =\sqrt{\frac{\eta _\infty }{\lambda _s k_0}}\), where we find that the thixotropic inverse rate of energy-dissipation \(\lambda _s \cdot k_0\) has an explicit impact on \(\tau _c\). A close inspection of \(\tau _c\)-definition serves here to explain the influence of its components, where the second Newtonian-plateau \(\eta _\infty\)-factor is modulated by the characteristic energy-dissipation rate \((\frac{1}{\lambda _s \cdot k_0})\) required for fluid-structure breakdown. Here, smaller \(\lambda _s \cdot k_0\)-products render larger energy dissipation rates required for structure fluidisation and, hence, larger critical stresses. Applying this reasoning to samples Healthy-1 and COPD-1, \(\tau _c\) appears higher for COPD-1 and indicates a larger critical stress: this difference ranges from \(\tau _c=0.18\) Pa for Healthy-1, to \(\tau _c=0.28\) Pa for COPD-1, which appear in quantitative agreement with the findings of Jory et al.20, who determined critical-stress values ranging from 0.2 to 0.5 Pa, and other reports in the literature.41

In Fig.2, the response provided by the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model in oscillatory shear appears consistent with the experiments reported by Jory et al.20. Here, a frequency sweep at fixed deformation amplitude of \(\gamma =0.01\) illustrated in Fig.2a, renders \(G'\)> \(G''\) in the frequency range below \(\omega = 100\) rad/s, exhibiting the behaviour of an elastic gel. Beyond this frequency, the order swaps and \(G''\) leads the rheological response. The model predictions describe quantitatively both moduli for frequencies below 10-20 rad/s for \(G'\), and around 50 rad/s for \(G''\), with \(R^2\ge 0.90\). At higher frequencies, moduli are under-predicted. Nevertheless, the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) follows the same trends observed experimentally. Furthermore, in Fig. 2b under a amplitude sweep at the fixed frequency of \(\omega =6.28\) rad/s, the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) constitutive equation describes qualitatively the plateaued responses of \(G'\) and \(G''\) up to a deformation of \(\gamma = 0.1\) units, with quantitative accuracy only for sample Healthy-1; from this point, predictions depart from experiments. The beginning of the strain-thinning response for experimental data is observed around \(\gamma = 0.1\), followed by a crossing point between \(G'\) and \(G''\) at \(\gamma = 1\), marking what experimentalist refer to as the yield point20,71, falling in the category of a purely strain-thinning behaviour62,70. Meanwhile, the theoretical curves display thickening, besides an over prediction of \(G'\), which results in the estimation of a higher yield point, and in a different type of viscoelastic response: weak-strain overshoot62,70. Notwithstanding this contrast between the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) description and the samples behaviour, the weak-strain overshoot viscoelastic response is seen in homologous systems, such as synthetic mucus samples under oscillatory shear, as reported by Lafforgue et al.80 (see Fig. 3 therein), and yield-stress fluids, like Xanthan gum solutions (see Fig. 7b in Hyun et al.70). In Fig. 2, vertical-grey dashed lines signal the \(\gamma \omega\)-value of 0.1 \(s^{-1}\) below which the model applies for these specific tests. One should note that the \(\gamma \omega\)-span studied by Jory et al.20 is notably large with respect to other studies, as will be evident in the distinct cases below. The BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model is capable of predicting strain-thinning viscoelastic responses under relatively small \(\lambda _1\)-values (see more details in the Appendix); such circumstances are characteristic of weakly viscoelastic materials, regime outside the commonplace sputum rheology reported5,11,17,19,20, for which the viscoelastic relaxation time ranges from some tenths to hundreds of units (see Tables 5-8). This explains why, even if we achieve a quantitative agreement in fitting steady shear flow curves and other experimental data sets, as we demonstrate in the following sections, there is room for improvement in describing LAOS data. This same position will be observed for all samples having amplitude-sweeps. We are performing studies on the predictive capabilities of the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model at the moment to extend the \(\gamma \omega\)-window and to capture the diversity of viscoelastic responses reported elsewhere62,70, which will appear subsequently.

BMP\(+\_\tau _p\)-model predictions in oscillatory shear. Experimental data by Jory et al.20. In these figures, a measure of the shear rate for the experiment-to-model-prediction departure is provided under a vertical dashed-grey line signalling the \(\gamma \omega =0.1\) level for non-linear response; here, one should consider the frequency \(\omega\) in Hz to maintain unit consistency.

In Fig. 3, we compare the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) modelling results for the Lissajous curves obtained under oscillatory deformations. It is worth mentioning that this type of plots highlight features that are not apparent in steady protocols or average viscoelastic material functions (\(G'\) and \(G''\)). Here, to achieve a satisfactory description of the Lissajous curves for the sample COPD-1 in Fig. 3, we considered an extra source of non-linearity in the form of a shear-banding mechanism, which provides additional shear-thinning features in the rheological response58. This shear-banding inclusion is in agreement with the characterisation reported by Jory et al.20, where they used the Power-Law constitutive equation to characterise their sputum rheology data under negative Power-Law indexes to fit their data; these same findings are particular of shear-banding systems58. As reported in Table 5, the shear-banding intensity-parameter \(\nu\) was considered only on the first stress mode, but its effects extend to large amplitudes of deformation. In line with the findings in Fig. 2, these elastic projections show agreement for relatively smaller amplitudes, for which the elliptical curves manifested by experiments are captured by the model. In contrast, for larger amplitudes, a stronger squared response is predicted, linked with the over-prediction of the plastic features of the sample. Nevertheless, it stands out that the shear-stress magnitudes are well-predicted with the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) equation, allowing for a \(R^2\ge 0.88\).

BMP\(+\_\tau _p\)-model predictions in oscillatory shear for samples Healthy-1 and COPD-1 at fixed \(\omega =6.28\) rad/s. Elastic Lissajous projections. Note the difference in plot scale across cases, marking different levels in the magnitude of shear stress \(\tau _{xy}\) and deformations \(\gamma\) applied. Symbols: Experimental data by Jory et al.20.

The extensional response of human mucus and sputum is very scarcely treated in the literature18, basically because its measurement is not easily attainable with commercial rheometers. Nevertheless, its importance has been recognised recently18, since the deformation dominating sputum expectoration process is of mixed shear-to-extensional nature. As such, exploration of the extensional response of mucus and sputum is performed here from a theoretical perspective, via prediction of the extensional viscosity coefficient (\(\eta _E\)) in steady state (see Fig.1), and the tensile-stress growth coefficient (\(\eta _E^+\)) (Fig. 4), which are the basic material functions defined for transient uniaxial extension.

In Fig.1, the steady uniaxial extensional viscosity trends predicted by the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) equation, using the parameter-set in Table 5, follow a strain-softening response: \(\eta _E\) decreases with extension rate \(\dot{\epsilon }\)-rise; here, predictions based on COPD-1 parameters display a notably larger extensional viscosity than the Healthy-1 case. It is noteworthy that this is a rather simple response in extension; as it will be shown latter, for the case of severe CF case, a complex strain-hardening and softening behaviour is reported - see on for further details.

In contrast, under transient uniaxial extension, highly non-linear trends are recorded from BMP\(+\_\tau _p\)-model predictions. In Fig.4, we chose to present the results in a dimensionless fashion, in order to make a fair comparison between results for samples Healthy-1 and COPD-1. Also, the span of selected Weissenberg numbers (\(Wi = \lambda _1\dot{\epsilon }_0\)) lie on the non-linear regime, i.e., in the strain-thinning zone. As it is apparent in this figure, both Healthy-1 and COPD-1 concur with the linear viscoelastic (LVE) limit, given at relatively small times and at low Wi numbers, which satisfies \(\eta ^+_E (\dot{\epsilon }, t) = 3\eta ^+(t)\). At \(Wi = 100\), we observe a monotonic response, produced by a competition between viscoelastic relaxation mechanisms that originates from having different relaxation times (a \(\lambda _1\)-spectra) and their contrasting magnitudes. Departure from this relatively-simple behaviour happens at smaller times with larger Wi, and it is characterised by multiple overshoots, being way more pronounced in the Healthy-1 case. Predictions of multiple overshoots are also reported in the work of Lele & Mashelkar81, and Islam82: the former study described the shear-induced transient rate-of-formation of hydrogen bonds in solutions of polar polymers, with the Energetically Crosslinked Transient Network (ECTN) model. The ECTN equation predicted more than one overshoot in the stress-growth coefficient (\(\eta ^+\))81; the latter study employed a variant of the Islam and Archer (IA) equation to model the response of polydisperse, linear polymers melts and solutions. Analogously, these authors observed two stress overshoots in the start-up plots of \(\eta ^+\), that were attributed to the contribution of different components, each one with widely-separated molar masses and relaxation times82. A similar plateaued response appeared also in the work of Varchanis et al.83, where the authors described the behaviour of a TVEP material in step-up shear with the model Saramito/Herschel Bulkley-Isotropic-Kinematic-Hardening (SHB-IKH).

Contrasting healthy, COPD and CF samples through rheological characterisation (Healthy-2, CF-2 and COPD-2 from Patarin et al.19)

In this section, the rheological characterisation of the experimental data reported by Patarin et al.19 with the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model is presented in terms of the comparison between control sample Healthy-2 data-set against ill-conditioned samples COPD-2 and CF-2. The objective of this section is to give evidence of the distinct rheological responses across COPD and CF affecting human sputum. One should note that the rheological protocols followed by Patarin et al.19 are not as exhaustive as those by Jory et al.20 (see Table 3); Patarin et al.19 only provide frequency and amplitude sweeps, over which we perform our theoretical rheological characterisation. Once a BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) parameter-set is determined, we provide predictions in steady simple shear, uniaxial extensional flow, and LAOS.

In Fig.5, we compare the experimental response of samples Healthy-2, COPD-2 and CF-2 against the model fitting results, under the parameter-sets listed in Table 6. Overall, the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) description of the experimental \(G'\) and \(G''\) moduli coincide qualitatively with the mechanical response of Patarin et al.19 sputum samples. The best quantitative agreement is achieved for frequency sweeps (\(R^2\ge 0.83\)), and like in the previous cases, the accuracy is reduced in amplitude sweeps (\(R^2 \ge 0.6\)). As expected, we see a viscoelastic gel-like response with \(G'\) dominating the SAOS window-of-observation at relatively small frequencies and deformation amplitudes. In contrast to previous findings for the data-set from Jory et al.20, the viscoelastic time scale \(\lambda _1\) for sample Healthy-2 is significantly larger (\(\lambda _1 = 600\) s), even compared to \(\lambda _1\)-values for samples COPD-2 (\(\lambda _1 = 180\) s) and CF-2 (\(\lambda _1 = 410\) s). This indicates that even for sputum samples sharing the same consistency (as for Healthy-1 and Healthy-2), they may display totally different transient responses, impacting the transport processes in physiological systems. It is noteworthy how the moduli response segregate across samples Healthy-2, COPD-2 and CF-2, for which Healthy-2 displays the weaker \(G'\) and \(G''\) response, followed by COPD-2 and surpassed by CF-2. Such differences in moduli magnitude may rely in the illness severity (as it is demonstrated later in this work), and the trends found within this theoretical characterisation may not be representative of all COPD and CF severity degrees, but rather of specific case-studies. Then, the experimental data fitted in Fig. 5 reveal that the magnitude of \(G'\) and \(G''\) on their own may not be a suitable way to distinguish one illness from another across isolated studies and would require complementary rheological tests, such as thixotropic tests to reveal other time-dependent responses. Nevertheless, \(G'\) and \(G''\) signals may be sufficient to identify the effects of an obstructive disease in isolated cases19, and can provide valuable information on its severity and treatment progress.

Predictions of shear and extensional viscosity are displayed in Fig. 6. There is a drop of four-to-five orders-of-magnitude in both \(\eta\) and \(\eta _E\) between the first and the second Newtonian plateau levels (see Table 6), finding the largest gap for sample CF-2. In the case of \(\eta _E\), we identify that all samples show a purely strain-softening response. As stated before, the product of the thixotropic parameters \(\lambda _s \cdot k_0\) determines the strength of the thinning response and \(\tau _c\), which is connected to the plastic features of sputum. Concerning the values of \(\tau _c\) reported in Table 6, we observe that the critical stress amounts \(\tau _c=0.07\) Pa for sample Healthy-2, whilst for samples COPD-2 and CF-2, \(\tau _c\) grows one and two orders-of-magnitude, respectively: \(\tau _c=0.63\) Pa for sample COPD-2 and \(\tau _c=1.29\) Pa for CF-2. This relationship between \(\tau _c\) and \(\lambda _s \cdot k_0\) marks a distinctive trend between the rheological response of sputum across illnesses, and provides evidence of the link between the plastic nature of sputum with its thixotropic features, captured theoretically with the BMP+\(\_\tau _p\) model for the first time in sputum and mucus rheological studies - at least, to the best of the our knowledge. This link between plasticity and thixotropy is a current topic in the field of theoretical modelling of complex materials73. These results indicate that rather than focusing only on the consistency of sputum, one should pay attention as well on the comparison between rheological timescales, where the viscoelastic and thixotropic characteristics reside.

BMP\(+\_\tau _p\)-model predictions in simple shear and uniaxial elongation for samples Healthy-2, COPD-2 and CF-2. See parameters in Table 6.

The BMP\(+\_\tau _p\)-model predictions under transient uniaxial extension are provided in Fig. 7. As expected from the steady results in Fig. 6, sample CF-2 displays the largest \(\eta ^+_E\) compared to samples Healthy-2 and COPD-2. A detailed inspection of the CF-2 gives evidence of weak overshoots occurring in the range \(10^{-4}<\dot{\epsilon }<10^{-3} s^{-1}\), which is qualitatively different from the other samples. In contrast to Fig 4, the predicted transient extensional response in Fig.7 for these cases appears rather simpler, possibly due to the experimental protocol used by Patarin et al.19, which hindered the determination of characteristic timescales), for which no transient test were performed, contrary to the characterisation protocol followed by Jory et al.20

Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the Lissajous elastic projections of samples and model description in oscillatory shear under the parameter sets in Table 6. We selected a frequency and amplitude span where the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) predictions were validated, according the fitting in Fig. 5: \(\omega =[1, 10]\) rad/s, and \(\gamma _0 = [0.1, 10]\), respectively. This range of deformation conditions hinders the appearance of a predominantly viscoelastoplastic regime on the Pipkin diagrams, as we cannot see the theoretical limit of a collapsed diagonal (marking a purely elastic response), nor a full circle (marking a purely viscous response in elastic projections63). Instead, one observes a variety of non-Newtonian signatures, that are qualitatively similar from case to case. At relatively small frequencies, and from small to moderate amplitudes (at least, moderate enough so the curves do not present sudden increments in stress), Lissajous curves display the typical trajectory of a post-yielded visco-plastic system84. At larger amplitudes, we observe sudden increments on the shear stress, that appear as over and undershoots. This signals the transition to a highly non-linear thixo-viscoelastoplastic regime85, where the time-dependent (although not necessarily transient) response, e.g. the stress-relaxation mechanism, is dominated not only by the \(\lambda _1\)-spectra, but also by the \(\lambda _s\) thixotropic timescales. At higher frequencies, the yielding occurs at even smaller amplitudes and the viscous contributions become relevant, since the curves acquire a rather elliptical shape, even though the frequency sweep in Fig. 5 demonstrates that \(G'>G''\) along the studied \(\omega\)-span. Then, through the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\)-model description, in contrast with the common-place consideration of sputum being an elasto-viscous solid, we infer that there exist some instances where its fluidisation cannot be determined by the \(G'=G''\) intersection point in amplitude sweeps, as this transition depends on both \(\gamma\) and \(\omega\). This is not surprising, considering that the yield point for thixotropic gels, such as sputum, is recognised to deviate from the expected responses of viscoelastoplastic materials in oscillatory shear71. Therefore, average material functions such as moduli condensate the general characteristics of the rheological behaviour of sputum, but the richness of its response deserves to be explored through dynamic, non-linear experimental and theoretical frameworks, such as LAOS and its representation in Pipkin diagrams, as the ones in Figs. 8 and 9, since they may reveal features that may be disease-dependent, as theoretically predicted in this work.

Also, in Figs. 8 and 9, we give explicit evidence of the relatively-stronger plastic features of samples COPD-2 and CF-2 via predictions with the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model, in connection with what happens physiologically with sputum in the airways, where the plastic features of the material rule its behaviour, blocking the airways18,47,67,68. Particularly in the regime of relatively small frequencies and large deformations, one may note the marked squared loops, which are a common signature for yield-stress fluids, as apparent in Fig.8 for the Healthy-2 case. Comparatively, in Fig.9, the CF-2 case displays markedly-squared with respect to sample Healthy-2 and COPD-2. As such, this kind of data in the form of a Pipkin diagram reveals distinctive behaviour across illnesses and may serve as a qualitative reference to determine the illness severity in affected patients, with the potential of serving as a tool to test and measure the effectiveness of mucolytic treatments, which have the main aim of restoring in some extent the consistency of healthy mucus and sputum to enhance the expectoration process11.

In a closer inspection of these highly-non-linear responses, the transition from a viscoelastoplastic to a thixo-viscoelastoplastic regime shown in Figs. 8 and 9, is evidenced in Fig. 10, where the viscous Lissajous projections (Figs. 10d, 10e and 10f) show that at larger amplitudes, secondary loops appear (given by the self-intersection of curves). According to Ewoldt & McKinley85, secondary loops occur when the thixotropic re-structuration timescale is smaller than the oscillatory deformation timescale, then allowing for microstructure build-up, or as a result of strong elastic non-linearity. Then, this predictions are susceptible to the choice on \(\lambda _s\) and \(k_0\) model parameters for each mode, whose determination requires a thorough rheological characterisation of the samples under exhaustive transient protocols. Unfortunately, the experimental data set of Patarin et al.19 did not include rheometric tests from where to obtain this specific information, e.g, hysteresis loops. Nevertheless, the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model is able to predict such transition signatures, giving further information on the thixo-viscoelastoplastic, gel-like nature of human sputum. Moreover, these kind of differentiated prediction may be an additional ingredient to a computationally-driven characterisation protocol of human mucus-sputum, from which distinct disease-conditioned behaviour may be captured and categorised through advanced rheological tests.

Extract from the Pipkin diagrams in Fig. 8 and 9, \(\omega = 2\) rad/s. Note the different scale in the shear stress needed to report Healthy-2 predictions in contrast with COPD-2 and CF-2, for which the ill-conditioned samples display shear-stress signals one order-of-magnitude larger than those under the healthy sample.

Contrasting CF samples through rheological characterisation (samples CF-3, CF-4, CF-5 from Nielsen et al.11, Dawson et al.5, and Tomaiuolo et al.17)

In this section, we provide evidence of the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) theoretical characterisation of the experimental results reported by Nielsen et al.11, Dawson et al.5, and Tomaiuolo et al.17, reflecting the influence of CF in human sputum, for which we contrast cases with different illness severity and its rheological manifestation.

Starting with the comparison between samples CF-3 and CF-4, we observe quantitative agreement between experimental data5,11 and the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) predictions in Figs.11 and 12 (with \(R^2\ge 0.81\), except for the amplitude sweep of CF-4). Listed in Table 7, we provide the model fitting parameters for samples CF-3 and CF-4. In addition to the main features identified in the rheological response of sample CF-2, which also appear in the case of CF-3 (i.e., a pronounced shear and strain thinning behaviour, and gel-like response in oscillatory shear), the hysteresis loop in Fig. 11b accounts for the strong thixotropic response of CF-sputum. This specific piece of information allowed us to determine the value of \(\lambda _s = 50\) s. The comparison of \(\lambda _s = 50\) s and \(\lambda _1 = 250\) s is in-line with general biogel characteristics, as reported by Ewoldt and McKinley86, where, for such kind of materials, the viscoelastic characteristic time \(\lambda _1\) is significantly larger than the re-structuration time \(\lambda _s\).

The rheometric-data and theoretical-prediction trends displayed in Fig. 12 for sample CF-4 are quite similar to those of CF-3 in Fig. 11, except for the behaviour of \(\eta ^+_E\) (see Fig.12c): here, \(\eta ^+_E\) displays a marked strain hardening-to-softening response, with a \(\eta _E\)-maximum registered at around \(10^{-2}\) \(s^{-1}\), followed by a steep drop of the extensional viscosity with extension-rate rise. This hardening around the transition from the linear to the non-linear regime, of which there would be no indication if the analysis of the response in uniaxial extensional flow were left out, appears also in further exploration of the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) model predictions for CF-affected sputum from the work of Tomaiuolo et al.17, in which samples of mild, moderate and severe CF sputum are characterised.

The BMP\(+\_\tau _p\)-model fittings and tabulated parameter-sets (see Table 8), for the data sets found in the work of Tomaiuolo et al.17, are based on the available steady simple shear apparent viscosity data and SAOS protocols, for which qualitative agreement is attained, but the quantitative description appears reduced by the out-of-tendency experimental points (if compared with the tendency followed by CF-2 to CF-4). First of all, the usual viscosity drop is captured under a span of some six orders-of-magnitude according with the relative level from the first (\(\eta _{p0}\)) to the second Newtonian plateaux (\(\eta _{\infty }\)), being the severe CF case the one with the largest apparent viscosity. In line with these trends, the severe CF-case holds the largest viscoelastic relaxation time \(\lambda _1=250\) s and the largest critical stress for \(\tau _c=10\) Pa.

BMP\(+\_\tau _p\)-model predictions in a frequency sweep in SAOS for CF-5 samples. Symbols: Experimental data from Tomaiuolo et al.17 \(R^2 = \{0.75, 0.93, 0.91\}\) corresponds to Mild, Severe and Very Severe samples, respectively.

Worthy of note are the extensional viscosity \(\eta _E\)-trends in Fig.13 extracted from predictions under the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\)-model formalism and its corresponding parameters-sets in Table 8. Here, the strain hardening-to-softening features of these CF-5 sputum samples correlates with the severity of illness. Reportedly, the CF-5 mild case displays a relatively mild strain-hardening rising trend at intermediate extension-rates in the range \(10^{-2}<\dot{\epsilon }<10^{-1}\) \(s^{-1}\), in contrast to the clinically-qualified as very-severe case, that displays a prominent \(\eta _E\)-peak rising over an order-of-magnitude from the Newtonian plateau at vanishing extension-rates, even appearing sooner in the extension-rate range of \(10^{-3}<\dot{\epsilon }<10^{-1}\) \(s^{-2}\). Recall that the strength of extensional-hardening correlates directly with the magnitude of the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) thixotropic rate of energy dissipation \((\frac{1}{\lambda _s \cdot k_0}\)), making this behaviour highly complex and related to a thixo-viscoelastoplastic response. In Table 8, the very-severe case holds the smallest \(\lambda _s \cdot k_0\) product across cases in Tomaiuolo et al.17, amounting \(\lambda _s \cdot k_0 = 10^{-6}\) units, and translating into a characteristic thixotropic energy-dissipation rate of \((\frac{1}{\lambda _s \cdot k_0})=10^{6}\) \(Pa \cdot s\). Fig.14 displays the response of \(G'\) and \(G''\) moduli, illustrating a direct correlation between CF-severity and moduli magnitude, with the severe case displaying the largest \(G'\) and \(G''\) levels. Here, the BMP\(+\_\tau _p\) performance is consistent with the expected magnitude and trends. It is important to note that the richness of the present analysis is due to comparison between cases associated to a different illness-severity degree. Making this kind of contrast through rheological characterisation for other diseases, such as COPD, could point out the uniaxial-extension material functions and the determination of characteristic time scales as the basis to develop biomarkers for treatment monitoring, even respiratory disease diagnosis.

Complementarily, in Fig.15, the transient extensional-deformation response of CF-5 cases is illustrated. We observe a switch from the strain-softening behaviour of samples CF-3 and CF-4, to a strain-hardening transient response for CF-5 samples, as the CF-5 curves lie above the LVE curve. This feature is accentuated in the severe and very-severe cases. These findings are relevant, since the physiological rates of extension in the airways (specially in the lungs42,87) fall within the deformation range where this hardening takes place, i.e., creeping flow conditions, explaining somehow the hindered process of expectoration that CF patients experience and the worsening of such symptom, according to the illness severity, and considering that uniaxial extension is relevant in the complex mixed shear-to-extensional flow of sputum, e.g. during the closure and reopening of airways45. Moreover, this increase in extensional viscosity, which can be referred to as extension-hardening, is also observed in homologue systems, such as mucin solutions65, and saliva 66. Until this point, such phenomenon has been predicted only for CF-affected sputum samples, but further rheometric measurements are needed to discard its manifestation in the case of COPD mucus and sputum. If discarded, this would serve as the basis for a diagnose biomarker. In this sense, we hypothesise that the rheological response in uniaxial extension may help to generate a more robust biomarker for pulmonary obstructive-disease diagnosis, assuming that thorough rheological transient and steady rheometric tests should be performed on sputum samples with different degrees of illness-severity.

Conclusions

In this work, we have carried out a thorough rheological characterisation on several samples of human mucus and sputum affected by COPD and CF5,11,17,19,20 using a model-variant in the BMP family of fluids; the BMP+\(\_\tau _p\) model in a multi-modal approach56,57,58. Such study involves the mathematical modelling of rheometric flows, such as steady and transient simple shear, uniaxial extension and oscillatory small and large amplitude deformations, i.e., SAOS and LAOS, which reveal a rich rheological response in linear and non-linear regimes, unveiling the complex thixo-viscoelastoplastic nature of human mucus and sputum. The correlation of these non-Newtonian features with the BMP+\(\_\tau _p\)-model parameters, through the critical stress for yielding and the corresponding thixotropic construction-destruction parameters, provides valuable information on the extensional response of human mucus and sputum for physiological airway-clearance functions18,44,45.