Abstract

Hypertension (HPT) is the leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and premature death worldwide. Currently, attention is given to various dietary approaches with a special focus on the role of micronutrient intake in the regulation of blood pressure. This study aims to measure the dietary intake of selected minerals among Malaysian adults and its association with HPT. This cross-sectional study involved 10,031 participants from the Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological study conducted in Malaysia. Participants were grouped into HPT if they reported having been diagnosed with high blood pressure [average systolic blood pressure (SBP)/average diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 140/90 mm Hg]. A validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was used to measure participants' habitual dietary intake. The dietary mineral intake of calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, sodium, and zinc was measured. The chi-square test was used to assess differences in socio-demographic factors between HPT and non-HPT groups, while the Mann–Whitney U test was used to assess differences in dietary mineral intake between the groups. The participants’ average dietary intake of calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, sodium, and zinc was 591.0 mg/day, 3.8 mg/day, 27.1 mg/day, 32.4 mg/day, 0.4 mg/day, 1431.1 mg/day, 2.3 g/day, 27.1 µg/day, 4526.7 mg/day and 1.5 mg/day, respectively. The intake was significantly lower among those with HPT than those without HPT except for calcium and manganese. Continuous education and intervention should be focused on decreasing sodium intake and increasing potassium, magnesium, manganese, zinc, and calcium intake for the general Malaysian population, particularly for the HPT patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension continues to be a public health problem despite many actions that have been taken to reduce its incidence across the world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 46% of adults with HPT are unaware that they have the condition, and of adults with HPT, only 1 in 5 (21%), approximately, have it treated (WHO, 2021). This multifactorial disease is responsible for more than 8 million deaths annually1,2.

Current evidence indicates that HPT is a multifactorial condition with genetic, sociodemographic, and behavioral risk factors, among others2,3. Some factors are non-modifiable, while others, such as physical activity and dietary intake, are well known modifiable risk factors. Individuals with HPT who adhered to their scheduled clinical sessions in a local public hospital were regularly advised to monitor their dietary intake in order to keep their blood pressure at an optimum level. They were also advised to reduce their salt intake and to include more vegetables and fruits in their diet.

Studies have shown a strong relationship between dietary intake and HPT, and several have proven the critical role of minerals (sodium, potassium, magnesium, zinc, calcium, selenium and copper) in food in maintaining an optimal blood pressure level4,5,6. Dietary sodium is a well-known risk factor of hypertension and there is strong association between salt and HPT4. There is significant evidence showing an association between calcium deficiencies and increases in blood pressure7,8. According to a recent longitudinal study, selenium might have an adverse impact on the development of HPT in the elderly9, and elevated selenium levels have been linked with increased levels of serum cholesterol10,11. A recent study has concluded that both deficiency and excessive dietary intake of iron would increase the risk of HPT12. Findings on associations between zinc, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, copper and blood pressure are inconsistent4,13,14,15,16,17,18,19.

To the best of our knowledge, the current studies in Malaysia were focusing on the association between dietary sodium and potassium intake with hypertension20,21. Studies regarding association between other dietary minerals and hypertension are still scarce in Malaysia. This study aimed to determine the dietary intake of selected minerals (calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, sodium and zinc) among Malaysian adults and its association with HPT.

Methodology

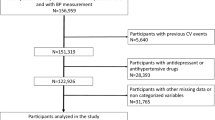

Study design and population

This was a community-based study, a sub-study under the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study conducted among adults aged 35–70 years old. The PURE study involved 27 countries, including Malaysia that focused on the impact of societal influences on the prevalence of selected non-communicable diseases. The extensive methodology of the overall PURE study has been described in previous studies22,23.

Measurements of dependent and independent variables

Blood pressure was measured by a trained research assistant using a calibrated Omron automatic digital monitor (Omron HEM-757; Omron Corp, Tokyo, Japan) after the participants had had 15 min of rest in a seated position. For purposes of this study, an individual with HPT is defined as one who reported having HPT and either (a) was receiving blood pressure-lowering medication or (b) had an average systolic blood pressure (SBP) of at least 140 mm Hg, or an average diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of at least 90 mm Hg, or both SBP and DBP that exceeded those levels. The readings of SBP and DBP were taken twice at five-minute intervals with appropriately sized cuffs based on a standard protocol. The average of the two readings was recorded and categorized as normal or HPT (SBP of 140 mm Hg or greater and/or DBP of 90 mm Hg or greater) according to the Malaysian Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) on Hypertension 201824.

The dietary intake of participants was measured using a validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ)25. A list of food and drink items was given to the participants, with pre-defined portion sizes and information on frequency of intake was sought with the following question: “During the past year, on average, how often have you consumed the following foods or drinks?” Responses ranged from “never” to “more than 6 times/day”. The dietary intake of each mineral—calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, sodium, and zinc—was estimated according to the recipes of dishes reported by the participants. To compute daily nutrient intake, this study utilized both the Malaysian Food Composition (MyFCD) database and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) food-composition database, modifying them as necessary by incorporating information from local food-composition tables and nutrient databases that contained recipes for mixed dishes commonly consumed in the local area26,27.

Physical activity levels were captured using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)27,28,29, and participants were also asked whether they had a medical diagnosis of other comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus (DM) and whether they had any family members with HPT and/or DM. Physical activity was classified as low if it was less than 600 Metabolic Equivalent (MET) minutes per week, and as high if it was equal to or greater than 600 MET minutes per week30,31.

Height and weight were measured using a portable stature meter and the TANITA (BC-558 Ironman®) segmental body composition analyzer, respectively. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (in kilograms) by the square of height (in meters). Overweight was defined as a BMI equal to or greater than 25 kg/m2 but less than 30 kg/m2, and obesity was defined as a BMI equal to or greater than 30 kg/m2.

All the information was collected using a questionnaire developed by the Population Health Research Institute (PHRI). The questionnaire was later revised and validated by the Malaysian team of researchers to ensure its suitability for the local population. Face and content validity were carried out by the research team, which comprised experts in public health-related studies.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 26. The general characteristics are presented as frequencies and percentages (categorical data) and median with interquartile range (IQR) of continuous data. This study used the Recommended Nutrient Intakes (RNI) for selected minerals by the Ministry of Health (MOH) to examine whether participants meet their requirement. The chi-square test was used to assess the differences between HPT and non-HPT groups for the following variables: age, sex, location, education level, SES, employment status, marital status, BMI, physical activity, co-morbidity, a family history of HPT, and a family history of DM. The difference between the HPT groups for the dietary intake of minerals was assessed through the Mann–Whitney U test. The statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All protocols were carried out in accordance with the relevant ethical guidelines and regulations. Each participant gave their informed written consents before taking part in the study. The Hamilton Health Sciences Research Ethics Board approved the study protocol (PHRI; Grant No. 101414), and local ethical clearance was obtained from the Research and Ethics Committee of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) Medical Center (project code: PHUM-2012–01) and the Research Ethics Committee of Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM).

Results

Table 1 shows the incidence of HPT, which was 43.5%. The majority of those with HPT were > 40 years old (48.0%), residing in rural areas (48.0%), having low education level (54.2%), and lower socio-economic status (48.2%). The majority of those with HPT were also currently unmarried (48.2%) and were overweight/obese (46.6%). Most of the respondents with HPT reported having co-morbidity of DM (68.4%) and a family history of HPT (48.7%) (Table 1).

Comparison of participants dietary intake of minerals with the Recommended Nutrient Intakes (RNI) for selected minerals by the Ministry of Health (MOH) are reported in Table 2. The average intakes of calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, sodium, and zinc were 591 mg/day, 3.8 mg/day, 27.1 mg/day, 32.4 mg/day, 0.41 mg/day, 1431 mg/day, 2.4 g/day, 27.1 µg/day, 4526 mg/day and 15 mg/day, respectively. For copper, phosphorus, and sodium, the dietary intake of these minerals was reported to be higher than RNI, especially sodium, which was three times higher. The dietary intake among participants were lower than the RNI for calcium, magnesium, manganese, potassium, and zinc. However, for iron and selenium, there were slight differences in the minerals' intake according to sex and age groups. Among those with HPT, the dietary intake of all the minerals except for calcium and manganese was significantly lower as compared to those without HPT.

Discussion

This study has shown that 43.5% of the participants had HPT. The findings revealed that this population had higher intake of sodium compared to RNI and lower intake of potassium and calcium, which are important for regulating blood pressure. In contrast, the intake of copper, iron, phosphorus, and selenium was higher than RNI among all participants, regardless of HPT status. Excessive intake of copper, iron, selenium, and phosphorus was associated with increased risk of HPT. The study also highlighted the higher incidence of HPT among older individuals, those who were overweight or obese, and those with a history of diabetes or family history of HPT or diabetes.

The incidence of HPT among this study population was 43.5%, which was higher than the incidence reported in the three consecutive NHMS reports for 2011 (32.7%), 2015 (30.3%), and 2019 (30.0%)24,32,33. This difference was expected, however, since NHMS covered individuals aged 18 years and above whereas this study limited its participants to adults 35 to 70 years old. The age range of 35 years and above is known to have a higher risk of NCDs, including HPT. This study found that individuals older than 40 years were more likely to have HPT than the younger participants (48.0% vs 18.1%). This may be caused by arterial stiffening due to aging, which is also closely associated with the progression of cardiovascular disease (CVD)34,35. Limited access to healthcare and low health literacy may have caused the late detection of these individuals’ health conditions, especially among less educated, those with low socioeconomic status, or residing in rural areas36. Additionally, HPT was more common among overweight or obese participants, those with history of diabetes or having family history of HPT or diabetes. Population-based studies have suggested that two-thirds of HPT can be directly attributed to obesity37,38. In addition to genetic factors, lifestyle choices (diet or food choices and physical activity levels), which tend to be similar among family members, have been demonstrated to be a strong risk factor for HPT39.

The findings highlighted the sodium intake of this population (4526 mg/day) was three times higher than the RNI (1500 mg/day), regardless of the HPT status. The sodium intake by this population is similar to the China population (4505 mg/day) but higher than the US population (3232 mg/day)40,41. However, this study showed that the sodium intake among those with HPT (4229.5 mg/day) was significantly lower compared to those without HPT (4757.5 mg/day). The finding is concurrent with a study done in the US that reported HPT and non-HPT groups consumed 3246.1 mg/day and 3410.1 mg/day of sodium respectively42. Sodium in the form of table salt, which is a common flavor enhancer widely used in cooking and processed and packaged foods, sauces, and snacks, is thought to be the cause of 40–50% of all types of HPT20,43. High consumption of sodium can trigger endogenous cardiotonic steroids (CTs), which act as Na+/K+ pump inhibitors44. These CTs may cause sodium retention (Na+ overload) and alter the vascular tone, causing damage to the endothelium, leading to arterial stiffness, and increasing the risk of HPT.

This study found those with HPT had a significantly lower intake of potassium (2.3 g/day) compared to those without HPT (2.4 g/day). The US population also shows similar patterns, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2007 to 2014 reported that potassium intake among HPT and non-HPT were 2.3 g/day and 2.5 g/day respectively42. Several studies have suggested a low dietary intake of potassium, may also lead to HPT. Potassium, which plays a vital role in cellular metabolism as well as electrolyte and fluid balance, affects blood pressure in a manner contrary to sodium due to the action of the sodium–potassium pump45. Adequate potassium intake aids in exerting hypotensive activity by suppressing the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). This leads to lower production of renin and angiotensin-II by inhibiting angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and by acting as an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB)46; as a result, it promotes better regulation of blood volume and cardiac output (CO). A sufficient intake of potassium also helps stimulate adenosine triphosphate (sodium/potassium ATPase), which promotes sodium excretion and results in decreased blood pressure47. Therefore, an adequate dietary intake of potassium is crucial in a daily diet, especially among those with high-sodium diets.

Although this study does not show any significant difference of dietary calcium intake between the HPT groups, the low dietary intake of calcium may hinder the ability of intracellular calcium ions to effectively regulate vascular tone, thereby affecting the blood pressure7,48. The calcium ion helps to enhance diuretic action, which aids in sodium secretion, encouraging better regulation of blood volume and CO via activation of SNS49. The low calcium intake found in this population was in line with previous studies, which reported dietary calcium intake of between 357 and 397.2 mg/day50,51,52. It was also supported by the findings of an International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) research committee, which concluded that countries from South, East, and Southeast Asia have the world’s lowest average calcium intake, which is often less than 400 mg/day53.

For copper, iron, phosphorus, and selenium, the dietary intake reported by all study participants was higher than the RNI. Similarly, the US population also consumed dietary copper, iron, phosphorus, and selenium higher than the recommended dietary allowances (RDA) by the WHO54. Although the intakes were much lower among those with HPT, they were still higher than the recommended values. Too much copper is said to suppress myosin-ATPase activity, which will lead to calcium overload, later resulting in elevated blood pressure17. Excessive iron intake has been shown to play a role in the development of HPT, increasing free radicals and oxidative stress, which leads to endothelial damage and the development of HPT55,56,57. As for selenium, too much of this mineral can adversely affect the major organs due to its pro-oxidant activity, which can disrupt the normal regulation of blood pressure58. Studies have also shown that excessive phosphorus intake activates the sympathetic nervous system, which accelerates cardiac activity and increases blood pressure59.

The intake of magnesium, manganese, and zinc among this study population was much lower than the recommended values. In contrast, the US population was reported to have dietary zinc intake higher than the RDA and the German population was reported to have adequate dietary manganese as recommended by the societies for nutrition in the region54,60. Studies have long linked the deficiency of these minerals with HPT4,61,62,63. Magnesium, which has an antiarrhythmic effect, may influence blood pressure levels by modulating the vascular tone62. Low extracellular manganese levels can adversely affect the production and release of nitric oxide (NO), resulting in the alteration of arterial smooth muscle tone leading to HPT14,64. As for zinc, its deficiency may elevate blood pressure by altering vascular tone63. Moreover, inadequate zinc intake is said to alter an individual’s taste sensitivity to salt, causing increased salt consumption, which is known to promote high blood pressure61.

The overall dietary intake of all the minerals except for calcium and manganese was significantly lower among those with HPT. Since this was a cross-sectional study, the temporal link between dietary intake and the occurrence of HPT could not be determined. Thus, the lower dietary intake among the respondents with HPT could potentially be explained by dietary modifications that the individuals made after having been diagnosed with HPT65,66,67. Without a proper understanding of the guidelines on diet modification, some individuals tend to reduce all types of food groups following an HPT diagnosis68. This can lead to an inadequate intake of some minerals that play a vital role in maintaining optimum blood pressure. Regardless of the insignificant difference of calcium intake between HPT and non-HPT groups, the overall intake of all participants was lower than the RNI level. It may be due to Asian cultural dietary habits, which commonly involve non-dairy diets69,70.

This study involved more than 10,000 participants from rural and urban areas of Malaysia who thoroughly reported their dietary intakes. Thus, the dietary intake of this study’s participants provided grounds for discussing the deficiency and overconsumption of minerals. The study’s main limitation was that dietary intakes was self-reported, which may have potentially overestimated or underestimated the dietary intakes of the respondents due to recall bias. Furthermore, the quantification of the minerals was calculated based on the meals that the respondents reported having consumed. This may be subject to slight inaccuracy since the calculation was based on general recipes for each dish. However, this study only included participants with plausible energy intake in the range of 500–5000 kcal to control the over- or underestimation of dietary intakes. Also, it is encouraged that future studies to analyze biomarkers of minerals in blood serum for a more accurate interpretation of the nutritional status of the study population.

Conclusion

Increased dietary intake of certain minerals, especially potassium, magnesium, manganese, zinc, and calcium (low in this population), as well as reduced intake of sodium and selenium, could positively modulate BP levels, thereby lowering the risk of HPT. Continuous professional education among doctors should be promoted to increase awareness and knowledge of the role these minerals play in common conditions such as hypertension. Public health campaigns to increase awareness of the importance of consuming an adequate amount of these minerals should also be carried out.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from PHRI but restrictions apply to the availability of the data, which were used under license for the current study, and are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from PHRI.

Abbreviations

- PURE:

-

Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological Study

- HPT:

-

Hypertension

- CVDs:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- MyFCD:

-

Malaysian Food Composition Database

- USDA:

-

United States Department of Agriculture

- IPAQ:

-

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PHRI:

-

Population Health Research Institute

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- RNI:

-

Recommended nutrient intakes

- RDA:

-

Recommended dietary allowances

- MOH:

-

Ministry of Health

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

References

Zhou, B. et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: A pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet 398(10304), 957–980 (2021).

Petrie, J. R., Guzik, T. J. & Touyz, R. M. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: Clinical insights and vascular mechanisms. Can. J. Cardiol. 34(5), 575–584 (2018).

Chia, Y. & Kario, K. Asian management of hypertension: Current status, home blood pressure, and specific concerns in Malaysia. J. Clin. Hypertens. 22(3), 497–500 (2020).

Chiu, H. F., Venkatakrishnan, K., Golovinskaia, O. & Wang, C. K. Impact of micronutrients on hypertension: Evidence from clinical trials with a special focus on meta-analysis. Nutrients 13(2), 588 (2021).

Filippou, C. D. et al. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet and blood pressure reduction in adults with and without hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv. Nutr. 11(5), 1150–1160 (2020).

Ozemek, C., Laddu, D. R., Arena, R. & Lavie, C. J. The role of diet for prevention and management of hypertension. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 33(4), 388–393 (2018).

Cormick, G., Ciapponi, A., Cafferata, M. L. & Belizán, J. M. Calcium supplementation for prevention of primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015(6), CD010037 (2015).

Villa-Etchegoyen, C., Lombarte, M., Matamoros, N., Belizán, J. M. & Cormick, G. Mechanisms involved in the relationship between low calcium intake and high blood pressure. Nutrients 11(5), 1112 (2019).

Su, L. et al. Longitudinal association between selenium levels and hypertension in a rural elderly Chinese cohort. J. Nutr. Health Aging 20(10), 983–988 (2016).

Bastola, M. M., Locatis, C., Maisiak, R. & Fontelo, P. Selenium, copper, zinc and hypertension: An analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2011–2016). BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 20(1), 45 (2020).

Chen, C. et al. The association between selenium and lipid levels: A longitudinal study in rural elderly Chinese. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 60(1), 147–152 (2015).

Wu, S. et al. Dietary intakes of total, nonheme, and heme iron and hypertension risk: a longitudinal study from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Eur. J. Nutr. 62(8), 3251 (2023).

McClure, S. T. et al. Dietary phosphorus intake and blood pressure in adults: A systematic review of randomized trials and prospective observational studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 109, 1264 (2019).

Xu, J. et al. The association between blood metals and hypertension in the GuLF study. Environ. Res. 202, 111734 (2021).

Bergomi, M. et al. Zinc and copper status and blood pressure. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 11(3), 166–169 (1997).

Carpenter, W. E., Lam, D., Toney, G. M., Weintraub, N. L. & Qin, Z. Zinc, copper, and blood pressure: Human population studies. Med. Sci. Monit. 19, 1–8 (2013).

Darroudi, S. et al. Association between hypertension in healthy participants and zinc and copper status: A population-based study. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 190(1), 38–44 (2019).

Vivoli, G., Bergomi, M., Rovesti, S., Pinotti, M. & Caselgrandi, E. Zinc, copper, and zinc- or copper-dependent enzymes in human hypertension. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 49(2–3), 97–106 (1995).

Yao, J., Hu, P. & Zhang, D. Associations between copper and zinc and risk of hypertension in US adults. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 186(2), 346–353 (2018).

Isa, Z. M. et al. Dietary sodium intake and its association with hypertension: A cross-sectional study in Selangor, Malaysia. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 71(Suppl 2), S68–S73 (2021).

Palaniveloo, L. et al. Low potassium intake and its association with blood pressure among adults in Malaysia: Findings from the MyCoSS (Malaysian Community Salt Survey). J. Health Popul. Nutr. 40, 7 (2021).

Jaafar, M. H. et al. New insights of minimum requirement on legumes (Fabaceae sp.) daily intake in Malaysia. BMC Nutr. 9(1), 6 (2023).

Chow, C. K. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in rural and urban communities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. JAMA 310(9), 959 (2013).

Institute for Public Health (IPH) NI of HM of HM. National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2019: Vol. I: NCDs—Non-Communicable Diseases: Risk Factors and Other Health Problems (2019).

Norimah, A. K. et al. Food consumption patterns: Findings from the Malaysian Adult Nutrition Survey (MANS). Malays. J. Nutr. 14(1), 25–39 (2008).

Miller, V. et al. Fruit, vegetable, and legume intake, and cardiovascular disease and deaths in 18 countries (PURE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet 390(10107), 2037–2049 (2017).

Teo K, Lear S, Islam S, Mony P, Dehghan M, Li W, et al. Prevalence of a Healthy Lifestyle Among Individuals With Cardiovascular Disease in High-, Middle-and Low-Income Countries The Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Study (2013). www.jama.com.

Yusuf, S. et al. Use of secondary prevention drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (the PURE Study): A prospective epidemiological survey. Lancet 378(9798), 1231–1243 (2011).

Dehghan, M. et al. Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet 390(10107), 2050–2062 (2017).

Alzahrani, H. et al. Impact of the 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic on health-related quality of life and psychological status: The role of physical activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(8), 3992 (2021).

Thanamee, S. et al. A population-based survey on physical inactivity and leisure time physical activity among adults in Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2014. Arch. Public Health 75(1), 1–9 (2017).

Institute for Public Health, National Institutes of Health M of HM. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2015 (NHMS 2015). Vol. II: Non-Communicable Diseases, Risk Factors & Other Health Problems. Vol. II, Ministry of Health Malaysia 1–291, 2015; http://www.iku.gov.my/images/IKU/Document/REPORT/nhmsreport2015vol2.pdf

Institute of Public Health. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2011 Fact Sheet NHMS 2011 Background. Kuala Lumpur; 2011.

McEniery, C. M., Wilkinson, I. B. & Avolio, A. P. Age, hypertension and arterial function. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 34(7), 665–671 (2007).

Sun, Z. Aging, arterial stiffness, and hypertension. Hypertension 65(2), 252–256 (2015).

Park, N. H., Song, M. S., Shin, S. Y., Jeong, J. H. & Lee, H. Y. The effects of medication adherence and health literacy on health-related quality of life in older people with hypertension. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 13(3), e12196 (2018).

Aniza, I. et al. Obesity related hypertension-gender specific analysis among adults in Tanjung Karang, Selangor, Malaysia. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 15, 41–52 (2015).

Mahadir Naidu, B. et al. Factors associated with the severity of hypertension among Malaysian adults. PLoS ONE 14(1), e0207472 (2019).

Ranasinghe, P., Cooray, D. N., Jayawardena, R. & Katulanda, P. The influence of family history of Hypertension on disease prevalence and associated metabolic risk factors among Sri Lankan adults. BMC Public Health 15(1), 576 (2015).

Fang, K., He, Y., Fang, Y. & Lian, Y. Dietary sodium intake and food sources among Chinese adults: Data from the CNNHS 2010–2012. Nutrients 12(2), 453 (2020).

Brouillard, A. M., Kraja, A. T. & Rich, M. W. Trends in Dietary Sodium Intake in the United States and the Impact of USDA Guidelines: NHANES 1999–2016. Am. J. Med. 132(10), 1199 (2019).

Wabo, T. M. C. et al. Association of dietary calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium intake and hypertension: a study on an 8-year dietary intake data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr. Res. Pract. 16(1), 74 (2022).

Grillo, S. Coruzzi, Salvi, Parati. Sodium Intake and Hypertension. Nutrients 11(9), 1970 (2019).

Paczula, A., Wiecek, A. & Piecha, G. Cardiotonic Steroids—A possible link between high-salt diet and organ damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(3), 590 (2019).

Ekmekcioglu, C., Elmadfa, I., Meyer, A. L. & Moeslinger, T. The role of dietary potassium in hypertension and diabetes. J. Physiol. Biochem. 72(1), 93–106 (2016).

Houston, M. C. Nutrition and nutraceutical supplements in the treatment of hypertension. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 8(6), 821–833 (2010).

Haddy, F. J. Role of dietary salt in hypertension. Life Sci. 79(17), 1585–1592 (2006).

Jayedi, A. & Zargar, M. S. Dietary calcium intake and hypertension risk: A dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 73(7), 969–978 (2019).

Garland, C. J., Bagher, P., Powell, C., Ye, X., Lemmey, H. A. L., Borysova, L., et al. Voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry into smooth muscle during contraction promotes endothelium-mediated feedback vasodilation in arterioles, 2017; https://www.science.org.

Lee, Y. Y. & Wan Muda, W. A. M. Dietary intakes and obesity of Malaysian adults. Nutr. Res. Pract. 13(2), 159 (2019).

Mirnalini, K. et al. Energy and nutrient intakes: Findings from the Malaysian Adult Nutrition Survey (MANS). Malays. J. Nutr. 14(1), 1–24 (2008).

Zainuddin, A. A. Current nutrient intake among Malaysia adult: Finding from MANS 20. Med. J. Malays. 70(1), 1–2 (2015).

Balk, E. M. et al. Global dietary calcium intake among adults: A systematic review. Osteoporos. Int. 28(12), 3315–3324 (2017).

Jiang, S. et al. Association between dietary mineral nutrient intake, body mass index, and waist circumference in U.S. Adults using quantile regression analysis NHANES 2007–2014. PeerJ. 2020(3), e9127 (2020).

Mori, N. & Hirayama, K. Long-term consumption of a methionine-supplemented diet increases iron and lipid peroxide levels in rat liver. J. Nutr. 130(9), 2349–2355 (2000).

Galan, P. et al. Low total and nonheme iron intakes are associated with a greater risk of hypertension. J. Nutr. 140(1), 75–80 (2010).

Kim, M. K. et al. Increased serum ferritin predicts the development of hypertension among middle-aged men. Am. J. Hypertens. 25(4), 492–497 (2012).

Drake, E. N. Cancer chemoprevention: Selenium as a prooxidant, not an antioxidant. Med. Hypotheses. 67(2), 318–322 (2006).

Kim, H. K., Mizuno, M. & Vongpatanasin, W. Phosphate, the forgotten mineral in hypertension. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 28(4), 345–351 (2019).

Sachse, B. et al. Dietary manganese exposure in the adult population in Germany—What does it mean in relation to health risks?. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 63, 1900065 (2019).

McDaid, O., Stewart-Knox, B., Parr, H. & Simpson, E. Dietary zinc intake and sex differences in taste acuity in healthy young adults. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 20(2), 103–110 (2007).

Romani, A. M. P. Beneficial role of Mg2+ in prevention and treatment of hypertension. Int. J. Hypertens. 2018, 1–7 (2018).

Şentürk, Ü. K., Kaputlu, I., Gündüz, F., Kuru, O. & Gökalp, O. Tissue and blood levels of zinc, copper, and magnesium in nitric oxide synthase blockade-induced hypertension. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 77(2), 97–106 (2000).

Bulka, C. M. et al. Changes in blood pressure associated with lead, manganese, and selenium in a Bangladeshi cohort. Environ. Pollut. 248, 28–35 (2019).

Alsaigh, S. A. S., Alanazi, M. D. & Alkahtani, M. A. Lifestyle modifications for hypertension management. Egypt J. Hosp. Med. 70(12), 2152–2156 (2018).

Di Daniele, N. et al. Effects of caloric restriction diet on arterial hypertension and endothelial dysfunction. Nutrients 13(1), 274 (2021).

Mahmood, S. et al. Non-pharmacological management of hypertension: in the light of current research. Irish J. Med. Sci. (1971) 188(2), 437–52 (2019).

Kwant, C. T., Ruiter, G. & Noordegraaf, A. V. Malnutrition in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 25(5), 405–409 (2019).

Chan, C. Y., Mohamed, N., Ima-Nirwana, S. & Chin, K. Y. Attitude of Asians to calcium and vitamin D rich foods and supplements: A systematic review. Sains Malays. 47, 1801–1810 (2018).

Tupe, R. & Chiplonkar, S. A. Diet patterns of lactovegetarian adolescent girls: Need for devising recipes with high zinc bioavailability. Nutrition 26(4), 390–398 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all PURE staff members at PHRI for continuous staff training and data management support. The authors are also grateful for the dedication and commitment of RESTU research assistants from UKM and UiTM who were involved in the data collection process. The voluntary participation of all respondents is greatly appreciated.

Funding

RESTU was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation of Malaysia (grant numbers 100-IRDC/BIOTEK 16/6/21(13/2007) and 07–05-IFN-BPH 010), Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia (grant number 600-RMI/LRGS/5/3(2/2011)), UiTM and UKM (PHUM-2012-01).The PURE study is an investigator-initiated study that is funded by the Population Health Research Institute (grant number 101414), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, with support from CIHR’s Strategy for Patient Oriented Research (through the Ontario SPOR Support Unit), as well as the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. This study also received unrestricted grants from several pharmaceutical companies (with major contributions from AstraZeneca [Canada], Sanofi-Aventis [France and Canada], Boehringer Ingelheim [Germany and Canada], Servier, and GlaxoSmithKline) and additional contributions from Novartis and King Pharma.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.N., Z.M.I., R. I, A.M.T and M.H.J; data collection, K.H.Y; data analysis, N.H.A.R, N.Z.A and K.H.Y; funding acquisition, N.H.I, R.I., and M.H.J; methodology, Z.M.I, N.M.N., N.H.I, R. I, A.M.T, M.H.J and K.H.Y; writing—original draft preparation, N.Z.A, A.Z and N.M.N., Z.M.I; writing—review and editing; N.Z.A, A.Z., N.M.N., N.H.A.R, Z.M.I, N.H.I, R.I, A.M.T, M.H.J, M.S.M.Y.; supervision, R.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mat Nasir, N., Md Isa, Z., Ismail, N.H. et al. A cross-sectional analysis of the PURE study on minerals intake among Malaysian adult population with hypertension. Sci Rep 14, 8590 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59206-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59206-0

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.