Abstract

Family history (FH) of alcoholism increases the risk of alcohol use disorder (AUD); however, the contribution of childhood trauma (CT) in this respect remains unclear. This study investigated the relationship between FH and AUD-related clinical characteristics (social onset, antisocial tendency, and severity of problematic alcohol consumption) through the mediating effects of childhood trauma (CT) and conduct behaviors (CB) in a Korean male population with AUD. A total of 304 patients hospitalized for AUD at 16 psychiatric hospitals completed standardized questionnaires, including self-rated scales. Mediation analyses were performed using the SPSS macro PROCESS. Individuals with positive FH (133, 44%) had greater CT and CB and more severe AUD-related clinical characteristics than those without FH (171, 56%). In the present serial mediation model, FH had significant direct and indirect effects on AUD-related clinical characteristics through CT and CB. Indirect effects were 21.3% for social onset, 46.3%, antisocial tendency, and 37.9% for problematic drinking. FH directly contributed to AUD-related clinical characteristics, and CT and CB played mediating roles. This highlights the importance of careful intervention and surveillance of adverse childhood experiences and conduct disorder to prevent and mitigate alcohol-related problems in individuals with FH of AUD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Family history (FH) of alcohol use disorder (AUD) in individuals is known to contribute to the development of AUD in subsequent generations, and numerous twin and adoptions studies showed that AUD is about 50% heritable1,2,3,4. In fact, having a positive family history (FH+) of AUD was found to be associated with more severe clinical characteristics, worse prognosis, and earlier onset of AUD than those without family history (FH−)5,6,7,8. Substantial evidence shows that FH+ individuals meet more diagnostic criteria for AUD and suffer from greater physical, inter-, and intrapersonal alcohol-related consequences8,9,10,11. Studies have found that FH is also closely related to behavioral and emotional problems that may predispose individuals to AUD, as FH+ individuals tend to have worse mood dysregulation and greater antisocial personality12,13. These findings demonstrate a close association between family history and AUD.

As family history is comprised of both genetic and environmental elements, both of these factors should be considered when studying the association between family history and AUD. Several genes associated with AUD have been identified, and many studies have revealed that genetic susceptibility is a crucial risk factor for AUD2,14,15. Furthermore, environmental factors such as childhood maltreatment and poor social support are also well-known risk factors for AUD development and severity1,3,16. Environmental factors can interact with genetic factors to increase the risk of AUD1. FH+ patients also reported greater early life adversity, which can independently increase the risk of AUD, regardless of FH12,17. This suggests a synergistic role for parental alcoholism in the pathogenesis and progression of AUD. Therefore, having biological parents with AUD is thought to expose genetically susceptible individuals to high-risk environments, which may increase the risk of AUD.

The relationship between FH and AUD can be affected by childhood experiences, particularly childhood trauma (CT). Early life trauma greatly increases the risk of substance abuse disorders through numerous mechanisms1,18. For instance, substance abuse can be a coping strategy for dealing with traumatic experiences, and dysfunctional family patterns may predispose an individual to early use of substances19. Such negative childhood experiences are more likely to be experienced by children with a FH of alcohol abuse13.

Furthermore, having parents with alcoholism can lead to the development of childhood behavioral problems, like antisocial behaviors, which are well-known risk factors for alcohol-related problems. Interestingly, conduct disorder is a predictor of regular alcohol use in early adolescence20. This can be explained by the role of impaired control during childhood, which can lead to earlier alcohol use, predisposing an individual to developing AUD in adulthood20. Such antisocial behaviors are more common in FH+ children, noting the importance of parental factors in the development of childhood personalities21,22,23. It can be thus said that childhood characteristics are crucial in the development of adult behaviors; and a FH of alcoholism has numerous genetic and environmental influences that can greatly increase the risk of AUD in individuals.

The current study aimed to explore the association between FH of alcoholism, negative childhood experiences such as CT and conduct behaviors (CB), clinical traits of AUD such as age at onset of social problems caused by drinking, antisocial tendency, and severity of problematic drinking. This study particularly investigated the mediating roles of CT and CB in the association between family history of alcoholism and age at social onset, severity of problematic drinking, and antisocial tendency using a serial multiple mediation model. We hypothesized that (1) the presence of a FH of alcoholism would be associated with certain AUD-related clinical characteristics, such as earlier onset, higher antisociality, and increased problematic drinking; (2) CT and CB would mediate the association between a FH of alcoholism and AUD-related clinical characteristics; and (3) CT and CB can act as serial mediators of the relationship between a FH of alcoholism and AUD-related clinical characteristics.

Methods

Participants

This study recruited 330 Korean male individuals with AUD from 16 psychiatric hospitals specializing in alcohol dependence with rehabilitation programs. All participants were inpatients who had been hospitalized primarily for alcohol detoxification rehabilitation. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) men aged between 20 and 70; (2) having a primary diagnosis of alcohol dependence according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV criteria; (3) being abstinent for at least one week prior to participation; and (4) having scored above the cut-off of eight points on the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT), which is indicative of hazardous drinking24,25. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) having a major psychiatric disorder such as psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, major depressive disorder, and anxiety disorder; (2) having substance dependence other than alcohol and tobacco use in the past six months based on the DSM-IV-TR criteria and clinician’s careful observation during hospitalization; (3) having scored less than 26 on the Mini Mental State examination—Korea version; (4) having mental retardation or organic mental disorder; and (5) having physical conditions preventing patients from complete self-reports and a structured, in-person interview26,27,28. All participants provided written informed consent before beginning the study, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital. This study was performed in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Measures

Participants completed a self-report questionnaire that included questions on date of birth, level of education, marital status, occupation, income, height, weight, and alcohol consumption. Of the 330, 26 did not provide appropriate answers to the questionnaire and thus were excluded from the analysis. The questionnaire included the following items:

-

1.

Family history of alcoholism.

To assess family history of alcohol abuse, participants answered “yes/no” to whether they had any family members with problematic drinking and then specified who it was. An individual with a FH+ of alcoholism was defined as having at least one biological parent or sibling with a problematic drinking habit.

-

2.

Social onset of AUD.

Social onset of AUD was defined as the earliest age at which participants experienced impairments in interpersonal, social, and occupational functioning due to harmful alcohol consumption. As part of the questionnaire, the patients were asked to specify the age at which they experienced social onset of AUD based on this definition. Two patients who did not provide answers were excluded from analysis.

-

3.

The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire—Version 4 + (PDQ-4 +) for antisocial tendency.

The PDQ-4 + is a 99-item yes/no tool used to screen for the 10 personality disorders of the DSM-IV axis II and the two personality disorders included in further studies that have shown reliability and validity in Korean populations29,30. Each “yes” response was counted as one point, and the sum of the points was used to evaluate the likelihood of having a personality disorder. Subscale scores were used to determine the presence of specific personality disorders. This study used a shortened 15-item version of the PDQ-4 + scale, which included eight questions assessing antisocial traits. The sum of the points for the eight items assessing antisocial traits was used to identify the extent of antisocial tendencies. Question 14 asked whether the participant had lied about many items in the questionnaire. 20 participants who answered “yes” to this question and four who did not answer were excluded from the analysis.

-

4.

Modified Korean version of The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-K) for severity of AUD.

The AUDIT is a 10-item scale used as a screening tool to assess the severity of hazardous drinking25. The Korean version of the AUDIT was used to measure AUD severity. Higher AUDIT-K scores correspond to a more problematic drinking pattern31.

-

5.

Modified Korean version of the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale (mPCCTS), Childhood Maltreatment Scale, and modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scale (mCTS) for childhood trauma.

CT was evaluated using the mean composites of childhood maltreatment, sexual abuse, and parental conflict. Childhood maltreatment was assessed using the mPCCTS, a 24-item scale based on the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale developed by Straus et al32,33. It measures psychological and physical maltreatment, and neglect of children experienced before the age of 18. Sexual abuse was measured using the “sexual abuse” section of the Childhood Maltreatment Scale, comprising 10 items assessing exposure to sexual violence before the age of 1834. The scale includes eight items that evaluate minor assaults, such as verbal abuse and physical touch, and two items that evaluate severe assault, such as oral sex and sexual intercourse. Childhood parental conflict experienced before the age of 18 years was measured using the mCTS35,36. This 10-item scale comprises verbal violence, minor physical violence, and severe physical violence between parents. The mean composite score of childhood maltreatment, sexual abuse, and parental conflict was calculated by summing the z-scores of the individual scales and dividing them by three.

-

6.

The Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire – Version 4+ (PDQ-4+) for conduct behaviors.

Of the eight questions assessing antisocial traits in the shortened version of the PDQ-4+ used in this study, the last question included 15 sub-questions that inquired about delinquent behavior that occurred before the age of 15. The sum of the points for this question assessed CB.

-

7.

Modified Korean version of The Beck Depression Inventory.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a 21-item self-report scale that measures symptoms of depression37,38,39. A modified Korean version of the BDI was used for this study, with each item comprised of three response choices ranging from absent to intense symptoms. The scores for each item were summed up to assess depression severity criteria.

-

8.

Modified Korean version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) is a 21-item self-report scale that measures severity of anxiety40,41. Each item on the BAI is comprised of four response choices in order from least to most severe symptoms. The total points for each item were added to assess anxiety severity. The modified Korean version of this scale was used in this study.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS 26.0 software for Mac (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistical analyses were first performed to evaluate the baseline differences between those with a FH of problematic alcohol consumption and those with no FH. Correlations between the variables and baseline differences were also found. Using Preacher and Hayes’ method, serial multiple mediation models of CT and CB were used as mediators of the relationship between FH of problematic alcohol consumption and one of three outcomes (social onset of hazardous drinking, antisocial tendency, and severity of problematic drinking)42. Further, a bootstrapping analysis with 10,000 re-samples was conducted. Analysis was performed using the PROCESS function in SPSS, and Model 6 was used for the multiple serial mediation model. Standardized coefficients were reported. Mediation was considered significant if the 95% bias-corrected and accelerated CIs (lower limit (LL) and upper limit (UL)) for the indirect effect (IE) did not include 043.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Of the 330 patients recruited, two who did not provide answers on social onset, 20 who answered “yes” to question 14 on the PDQ-4+ , and four who did not answer to question 14 on the PDQ-4+ were excluded from the statistical analysis. A total of 133 (44%) FH+ participants and 171 (56%) FH- participants were included in the analysis. It was found that FH+ individuals experience more childhood maltreatment, parental conflict, and conduct behaviors. This group also was younger and had higher levels of depression. Furthermore, FH+ patients had earlier social onset, greater antisocial tendency, and higher severity of problematic drinking.

Spearman’s correlations between CT, CB, social onset, antisocial tendency, and AUDIT score are shown in Table 2. There were significant correlations between all five variables. CT, CB, antisocial tendencies, and problematic drinking were positively correlated with each other, and social onset was negatively correlated with the other variables.

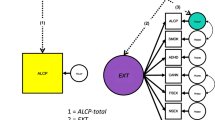

Serial multiple mediation models illustrating the relationships between family history and social onset, antisocial tendencies, and AUDIT scores in patients with AUD are presented in Fig. 1. Significant direct (SO: β = − 0.37, AS: β = 0.21, AD: β = 0.23) and total effects (SO: β = 0− 0.47, AS: β = 0.39, AD: β = 0.37) of FH on social onset, antisocial tendency, and severity of problematic drinking were found.

Path analysis linking family history of AUD with social onset (a), antisocial tendency (b), and severity of problematic drinking (c). a1 = direct effect of family history on childhood trauma; a2 = direct effect of family history on conduct behaviors; a3 = direct effect of childhood trauma on conduct behaviors; b1 = direct effect of childhood trauma on social onset (a), antisocial tendency (b), or severity of problematic alcohol consumption(c); b2 = direct effect of conduct behaviors social onset (a), antisocial tendency (b), or severity of problematic alcohol consumption (c); c’ = total effect of family history on social onset (a), antisocial tendency (b), or severity of problematic alcohol consumption (c); c = direct effect of family history on social onset (a), antisocial tendency (b), or problematic alcohol consumption (c). *p < 0.05. PDQ: Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4.

Table 3 summarizes these indirect effects. The indirect effect of FH on social onset through the path FH−> CT−> CB−> SO (β = − 0.0230, SE = 0.0123, 95% CI − 0.0513, − 0.0037) was significant. There was a significant indirect effect through CT (β = − 0.0510, SE = 0.0266, 95% CI − 0.1063, − 0.0030) and no significant effect through CB (β = − 0.0267, SE = 0.0193, 95% CI − 0.0715, 0.0027). The indirect effect of FH on antisocial tendency through the path FH−> CT−> CB−> AS (β = 0.0771, SE = 0.0244, 95% CI 0.0333, 0.1298) was significant. Contrastingly, the indirect effects through CT (β = 0.0138, SE = 0.0258, 95% CI − 0.0312, 0.0716) and through CB (β = 0.0895, SE = 0.0522, 95% CI − 0.0075, 0.1982) were not significant. The indirect effects of FH on severity of problematic drinking through the path FH−> CT−> CB−> AD (β = 0.0335, SE = 0.0140, 95% CI 0.0101, 0.0646) and through CT (β = 0.0680, SE = 0.0311, 95% CI 0.0147, 0.1356) were significant. However, the indirect effect through CB was not significant (β = 0.0386, SE = 0.0258, 95% CI − 0.0043, 0.0964).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the relationship between FH and three AUD-related clinical characteristics (social onset, antisocial tendency, and severity of problematic alcohol consumption) through the serial mediating effects of CT and CB. Our findings showed that CT and CB significantly mediated this relationship, suggesting that adverse childhood experiences and behavioral problems together contribute to the pathogenesis of AUD. Additionally, the direct effects of FH on AUD-related clinical characteristics were found to be significant. These findings support previous theories that gene-environment interactions contribute to the disease phenotype in FH + individuals1,44,45.

In the serial mediation models, CT and CB partially mediated the relationship between FH and AUD-related clinical characteristics. In the mediation model of FH on social onset, the total indirect effect was significant (β =− 0.1007) and accounted for 21.3% of the total effect. The indirect effect of FH via CT (β = − 0.051) and that of the serial mediation via CT and CB (β = − 0.023) accounted for 10.9% and 4.9% of the total effect, respectively. The total indirect effect of FH on antisocial tendency was also significant (β = 0.1804), accounting for 46.3% of the total effect, and antisocial tendency was indirectly affected by FH serially through CT and CB (β = 0.0771), which accounted for 19.8% of the total effect. FH also had a significant total indirect effect on the severity of problematic drinking (β = 0.1403), and this accounted for 37.9% of the total effect. The indirect effect of FH via CT (β = 0.068) and that of the serial mediation via CT and CB (β = 0.0335) accounted for 18.4% and 9.1% of the total effect on severity of problematic drinking, respectively. These findings suggest that a FH is likely to predispose a child to experiencing trauma during childhood, which can trigger the development of CB. The cumulative effects of such stressors could lead to an earlier onset of social problems caused by drinking, greater antisocial tendency in adulthood, and more problematic consumption of alcohol. These findings corroborate previous studies showing that FH is a risk factor for both AUD development and severity2,3,4,10, and the results support our hypothesis that these effects are mediated by CT and CB.

Notably, we found a significant direct effect of FH on AUD-related clinical characteristics, which was greater than the indirect effects of CT and CB (78.7% vs. 21.3% for social onset, 53.8% vs. 46.3% for antisocial tendency, and 62.2% vs. 37.9% for severity of problematic drinking). These findings suggest that other environmental factors not included in this study may contribute to AUD pathogenesis and progression and that genetic aspects of FH may heavily influence AUD. In Korean men, lower educational status, lower service occupation, greater depressive symptoms, and being divorced or bereaved are associated with heavier drinking46,47. These mediators were not included in our analysis, which may account for the weaker indirect effects of FH.

Previous studies on childhood risk factors for AUD in FH + individuals have focused on adverse childhood experiences such as physical, sexual, or emotional abuse since they are known to be prevalent in families with a parental history of alcoholism. Our study not only considered CT, but also examined the additional effects of childhood misconduct on AUD. Pathways that included both mediators had significant indirect effects in all three models, suggesting that a causal effect could exist between them. A longitudinal study previously found that childhood maltreatment increased the risk of developing conduct disorder, which could be applicable to patients with CB48. Another study explained that early life stress leads to impulsive decision-making in children, a hallmark of both CB and substance abuse, further supporting the hypothesis made in this study49. Greater stress induced by multiple traumas during childhood can lead to various harmful outcomes, including the development of CB, thus predisposing already high-risk populations to develop worse clinical outcomes of AUD.

Interestingly, as shown in the Fig. 1, while three models showed significant serial mediating effects of CT and CB between FH and outcomes, no significant direct effect of FH on CB was found, suggesting a mediating role of CT between FH and CB. This reflects that in FH + AUD patients, CT is a critical risk factor for the development of CB. Previous studies have found CT to be a risk factor for the development of externalizing behaviors in adolescence, and CT is also associated with increased risk of alcoholism1,12,50. Children who are exposed to trauma develop impaired executive functioning, leading to problems with impulsivity control, and such traits have been shown to predict increased adolescent drinking and alcohol-related problems51,52. These findings implicate need for routine monitoring and surveillance for childhood abuse and neglect in individuals with a FH of AUD to reduce the risks of alcohol-related problems.

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of this study limits the conclusions that can be drawn regarding the causal relationships among the variables. For instance, CT may not have occurred before CB, and antisocial tendencies may have been a precursor rather than an outcome of AUD. Second, only CT and CB were included as mediators in our study, which may not completely explain the relationship between FH and AUD-related clinical characteristics, as other mediators may be involved in the pathogenesis of AUD. Third, since the data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire, there is a possibility that the respondents did not answer accurately. In this study, the participants may not have recalled their FH accurately or answered correctly about their symptoms, which would have led to incorrect relationships between the mediator and outcome variables. Fourth, since the present study included only male patients with severe AUD requiring hospitalization, the results may not be applicable to females or those with mild-to-moderate cases of AUD. In addition, since we excluded patients with major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder, which often co-occur with AUD, to reduce heterogeneity of our sample, our findings may not be applicable to some AUD patients with diverse clinical levels of comorbid internalizing or externalizing disorders. Considering the presence of various comorbid psychopathologies in AUD, further research using a larger and a more diverse pool of participants is required to confirm the present findings.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that FH directly and indirectly contributes to earlier social onset of alcohol-related problems, greater antisocial tendency, and more severe problematic drinking. The study found that CT and CB partially mediated the relationship between FH and AUD-related clinical characteristics. These findings highlight the importance of careful surveillance and an early identification of adverse childhood experiences and conduct problems to reduce the burden of childhood maltreatment and to prevent and mitigate alcohol-related problems in vulnerable individuals with a FH of alcoholism.

Data availability

Raw data are not publicly shared because the participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared openly. However, the minimal datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Enoch, M. A. Genetic and environmental influences on the development of alcoholism: Resilience vs. risk. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1094, 193–201 (2006).

Heath, A. C. et al. Genetic and environmental contributions to alcohol dependence risk in a national twin sample: Consistency of findings in women and men. Psychol. Med. 27(6), 1381–1396 (1997).

Magnusson, Å. et al. Familial influence and childhood trauma in female alcoholism. Psychol. Med. 42(2), 381–389 (2012).

Verhulst, B., Neale, M. C. & Kendler, K. S. The heritability of alcohol use disorders: A meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychol. Med. 45(5), 1061–1072 (2015).

Frances, R. J., Timm, S. & Bucky, S. Studies of familial and nonfamilial alcoholism I. Demographic studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 37(5), 564–566 (1980).

Latcham, R. W. Familial alcoholism: Evidence from 237 alcoholics. Br. J. Psychiatry 147, 54–57 (1985).

Hill, S. Y., Shen, S., Lowers, L. & Locke, J. Factors predicting the onset of adolescent drinking in families at high risk for developing alcoholism. Biol. Psychiatry 48(4), 265–275 (2000).

Lee, S. H., Lee, B. C., Kim, J. W., Yi, J. S. & Choi, I. G. Association between alcoholism family history and alcohol screening scores among alcohol-dependent patients. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 11(2), 89–95 (2013).

Lai, D. et al. Evaluating risk for alcohol use disorder: Polygenic risk scores and family history. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 46(3), 374–383 (2022).

Boyd, S. J., Plemons, B. W., Schwartz, R. P., Johnson, J. L. & Pickens, R. W. The relationship between parental history and substance use severity in drug treatment patients. Am. J. Addict. 8(1), 15–23 (1999).

Haeny, A. M. et al. Individual differences in the associations between risk factors for alcohol use disorder and alcohol use-related outcomes. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 35(5), 501–513 (2021).

Sorocco, K. H., Carnes, N. C., Cohoon, A. J., Vincent, A. S. & Lovallo, W. R. Risk factors for alcoholism in the Oklahoma Family Health Patterns project: Impact of early life adversity and family history on affect regulation and personality. Drug Alcohol Depend. 150, 38–45 (2015).

Acheson, A., Vincent, A. S., Cohoon, A. J. & Lovallo, W. R. Defining the phenotype of young adults with family histories of alcohol and other substance use disorders: Studies from the family health patterns project. Addict. Behav. 77, 247–254 (2018).

Li, D., Zhao, H. & Gelernter, J. Strong protective effect of the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (ALDH2) 504lys (*2) allele against alcoholism and alcohol-induced medical diseases in Asians. Hum. Genet. 131(5), 725–737 (2012).

Sanchez-Roige, S. et al. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in two population-based cohorts. Am. J. Psychiatry 176(2), 107–118 (2019).

Enoch, M. A. The role of early life stress as a predictor for alcohol and drug dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 214(1), 17–31 (2011).

Fenton, M. C. et al. Combined role of childhood maltreatment, family history, and gender in the risk for alcohol dependence. Psychol. Med. 43(5), 1045–1057 (2013).

Pilowsky, D. J., Keyes, K. M. & Hasin, D. S. Adverse childhood events and lifetime alcohol dependence. Am. J. Public Health 99(2), 258–263 (2009).

Coyer, S. M. Women in recovery discuss parenting while addicted to cocaine. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 28(1), 45–49 (2003).

Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Newman, D. L. & Silva, P. A. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 53(11), 1033–1039 (1996).

Das Eiden, R., Leonard, K. E. & Morrisey, S. Paternal alcoholism and toddler noncompliance. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 25(11), 1621–1633 (2001).

Foley, D. L. et al. Risks for conduct disorder symptoms associated with parental alcoholism in stepfather families versus intact families from a community sample. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 45(4), 687–696 (2004).

Schaeffer, K. W., Parsons, O. A. & Errico, A. L. Abstracting deficits and childhood conduct disorder as a function of familial alcoholism. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 12(5), 617–618 (1988).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR). 4th edn (Amer Psychiatric Pub, 2000).

Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., de la Fuente, J. R. & Grant, M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction 88(6), 791–804 (1993).

Kang, Y. W., Na, D. L. & Hahn, S. H. A validity study on the korean mini-mental state examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J. Korean Neurol. Assoc. 15(2), 300–308 (1997).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12(3), 189–198 (1975).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM-5. 5th edn (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013).

Hyler, S. E. Personality diagnostic questionnaire-4 (New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1994).

Kim, D. I. The preliminary study of reliability and validity on the Korean version of personality disorder questionnaire-4+. J. Korean Neuropsychiatric Assoc. 156(3), 525–538 (2000).

Version of Personality Disorder Questionnaire-4+. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association 156(3):525–38. (2000).

Kim, J. S., Oh, M. K., Park, B. K., Lee, M. K. & Kim, G. J. Screening criteria of alcoholism by alcohol use disorders identification test(AUDIT) in Korea. J. Korean Acad. Fam. Med. 20(9), 1152–1159 (1999).

Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Finkelhor, D., Moore, D. W. & Runyan, D. Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child conflict tactics scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse Negl. 22(4), 249–270 (1998).

Kim, M. & Lee, E. The influence of abused childhood experiences, exposure to suicide and exposure to suicide news on suicidal thought among adolescents: The mediating role of goal instability. Korean J. Youth Stud. 18(12), 403–429 (2011).

Jang, H. & Lee, J. The development of a child abuse assessment scale. J. Korean Counc. Child. Rights. 3(1), 77–96 (1999).

Straus, M. A. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. J. Marriage Fam. 41(1), 75–88 (1979).

Kim, J.-Y., Cho, C.-B. & Chung, Y.-K. The effect of domestic violence experience on adolescents’ violence towards their parents and the mediating effect of the internet addiction. Korean J. Soc. Welf. 60(2), 29–51 (2008).

Chung, Y. C. et al. Korean version (K—BDI ): Reliability and factor analysis. Korean J. Psychopathol. 4(1), 77–95 (1995).

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J. & Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 4, 561–571 (1961).

Hahn, H. et al. A standardization study of beck depression inventory in Korea. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 25, 487–502 (1986).

Kim, Z. S. & Yook, S. P. A clinical study of the Korean version of beck anxiety inventory: Comparative study of patients and non-patient. Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 16, 185–197 (1997).

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G. & Steer, R. A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 56(6), 893–897 (1988).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40(3), 879–891 (2008).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 36(4), 717–731 (2004).

Meyers, J. L. et al. Childhood adversity moderates the effect of ADH1B on risk for alcohol-related phenotypes in Jewish Israeli drinkers. Addict. Biol. 20(1), 205–214 (2015).

Dick, D. M. & Kendler, K. S. The impact of gene-environment interaction on alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Res. 34(3), 318–324 (2012).

Choe, S. A., Yoo, S., JeKarl, J. & Kim, K. K. Recent trend and associated factors of harmful alcohol use based on age and gender in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 33(4), e23 (2018).

Kim, Y. Y., Park, H. J. & Kim, M. S. Drinking trajectories and factors in Koreans. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(16), 8890 (2021).

Docherty, M., Kubik, J., Herrera, C. M. & Boxer, P. Early maltreatment is associated with greater risk of conduct problems and lack of guilt in adolescence. Child Abuse Negl. 79, 173–182 (2018).

Liu, R. T. Childhood maltreatment and impulsivity: A meta-analysis and recommendations for future study. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 47(2), 221–243 (2019).

Appleyard, K., Egeland, B., van Dulmen, M. H. & Sroufe, L. A. When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 46(3), 235–245 (2005).

Jones, C. B., Meier, M. H., Corbin, W. E. & Chassin, L. Adolescent executive cognitive functioning and trait impulsivity as predictors of young-adult risky drinking and alcohol-related problems. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 35(2), 187–198 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (2021M3E5D9025022, RS-2023-00209077, and 2019R1A2C1084611). The funding source did not influence the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study. SJK, SSH, and JIK conceptualized and planned the study. SSH and SJK carried out the data collection and management. MJH, SJK, and JIK performed the statistical analyses and data interpretation. MJH and JIK wrote the manuscript. STK, HWK and CIP provided scientific input and helped edit the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, M.J., Kim, S.T., Park, C.I. et al. Serial mediating effects of childhood trauma and conduct behaviors on the impact of family history among patients with alcohol use disorder. Sci Rep 14, 7196 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57861-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57861-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.