Abstract

To investigate the efficacy of the Korean version of the Minnesota low vision reading chart. A Korean version consisting of 38 items was prepared based on the MNREAD acuity chart developed by the University of Minnesota. A linguist composed the representative sentences, each containing nine words from second and third grade levels of elementary school. Reading ability was measured for 20–35-year-old subjects with normal visual acuity (corrected visual acuity of logMAR 0.0 or better). The maximum reading speed (words per minute [wpm]) for healthy participants, reading acuity (smallest detectable font size), and critical print size (smallest font size without reduction of reading speed) were analyzed. The average age of the subjects was 28.3 ± 2.6 years (male:female ratio, 4:16). The average reading time for 38 sentences was 3.66 ± 0.69 s, with no differences in the average maximum reading speed between sentences (p = 0.836). The maximum reading speed was 174.2 ± 29.3 and 175.4 ± 27.8 in the right and left eye, respectively. Reading acuity was measured as logMAR 0.0 or better in 80% of the cases. All subjects showed a critical print size of 0.2 logMAR or better. The overall reading ability can be measured using the Korean version of the MNREAD acuity chart, thereby making it useful in measuring the reading ability of those with Korean as their native language.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Visual acuity is a widely used essential component of evaluating visual function. More precisely, reading skills are more commonly used in real life than identifying individual letters. However, as conventional visual acuity charts are composed of individual letters, reading skills cannot be evaluated. Moreover, since various dysfunctions, such as visual field defects, loss of contrast sensitivity, or ocular movement abnormalities, can affect reading speed, it is necessary to investigate reading speed in patients with low vision due to corneal opacity, cataracts, retinal disorders, or optic neuropathies1,2,3.

Reading charts, such as the Bailey-Lovie word chart, Colenbrander English continuous text, RADNER reading acuity chart, and MNREAD chart have been introduced by the International Council of Ophthalmology4,5. In 1989, Mansfield and Legge introduced Minnesota Low-Vision Reading chart, which is based on the computer to measure reading speed. Afterward, This test was redesigned in print form in 1993, and it was called the MNREAD Acuity Chart. The MNREAD Acuity Chart consists of sentences from second- and third-grade reading materials, which contain 60 characters and range from 1.3 to − 0.5 logMAR. This chart can measure reading ability, including reading acuity, critical print size, and maximum reading speed and reading accessibility index6. English, German, French, Spanish, Dutch, and Turkish versions of the MNREAD acuity chart are currently available.

The Korean alphabet, called Hangul, comprises two or three parts (initial consonant, middle vowel, and optional ending consonant letters [e.g., for 강, ㄱ is the initial consonant, ㅏ is the middle vowel and ㅇ is the ending consonant). Therefore, it is difficult to develop a Korean version of the visual acuity chart because these characters were not based on any alphabet, unlike Chinese or Japanese characters7. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the efficacy of the Korean version of the reading acuity chart based on the MNREAD acuity chart.

Methods

Representative sentences were obtained from second- and third-grade primary school materials by a linguist (YSK). Thirty-eight items were prepared with similar maximum reading speeds for the right and left eyes. One sentence consisted of nine words, and the font used was MyeongjoChe (Fig. 1). Similar to other language versions of the MNREAD chart, the print size ranged from 1.3 to − 0.5 logMAR. The height of the characters was designed according to the English version of MNREAD chart. This study (no.: P01-202111-21-012) was approved by the institutional review board, and was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Korean version of the MNREAD acuity chart. For example, the contents of Korean are as follows; 8 M size; When you step on fallen autumn leaves, you hear a strange crunching sound. 6.3 M size; We laughed so much that our belly button fell out at the funny look of our friend. 5 M size; The snow is falling, the whole world is white, and the scenery is like a painting. 4 M size; It's nice to go to the zoo to see strange animals and take pictures.

Twenty healthy adults who visited the clinic for refractive surgery from February to July 2021 were included. Complete ophthalmologic examinations, including slit-lamp, fundoscopy, visual field, and refraction tests, were performed. The exclusion criteria were as follows: age > 35 years, far vision < logMAR 0.0, near vision < logMAR 0.0, reading disabilities, visual field defects, and low educational status.

The Korean chart was commissioned by the Precision Vision Company (Woodstock, USA) and created according to the guidelines of the MNREAD acuity chart. The test was conducted under the following conditions: the chart’s white background’s luminance was 80 cd/m2, and the testing distance was 40 cm. Each sentence was to be read out aloud as quickly and accurately as possible. The next lines were covered so that the subjects could not preview those sentences. Reading acuity was determined by the smallest print size that the patient could read without making errors, and was calculated as follows: 1.4 − (sentences × 0.1) + (wrong words × 0.011). The maximum reading speed (words per minute [wpm]) was defined as the maximum reading speed for prints larger than the critical print size, and was calculated as follows: speed = 60 × (9 − wrong words)/reading time in seconds. The critical print size was the smallest print that the patient could read with maximum speed. Two panels on the left and the right were created and compared and analyzed.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Reading acuity was analyzed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study, No; P01-202111-21-012, was approved by the Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy (KoNIBP) and conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The KoNIBP completely waived the requirement to obtain informed consent, and instead approved a consent procedure, which does not include some or all of the required elements of informed consent, provided that the research involves no more than minimal risk.

Results

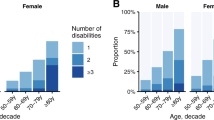

The average age of the experimental group was 28.3 ± 2.6 years (male:female ratio = 4:16). Reading acuity was measured as logMAR 0.0 or better in 80% of cases, the smallest size readable (reading acuity) was found to be the most frequent at 0.2 print size (Fig. 2A). The Maximum reading speed was 174.2 ± 29.3 and 175.4 ± 27.8 in the right and left eye, respectively. Reading speed plateaued at around 0.2 logMAR (Fig. 3). Additionally, there was no significant difference between the right and left panels (p = 0.372). However, there were significantly different maximum reading speeds with respect to the MNREAD acuity chart (p < 0.001, intraclass correlation coefficient). Regarding the critical print size, approximately half of the group had a 0.0 logMAR letter size (Fig. 2B), while all subjects showed a critical print size of 0.2 logMAR or better. The average reading time for the 38 sentences was 3.66 ± 0.69 s, with no difference in the average reading speeds between sentences (p = 0.836) (Table 1).

Discussion

This study provides represented data for the Korean MNREAD chart in the young adult, and the present data, including reading acuity, maximum reading speed, and critical print size, could be representative values to compare normal people and low vision patients in Korean populations.

MNREAD acuity charts have been developed in different languages8,9,10. Each language has its own characteristics. In terms of Korean consonants (e.g., ㄷ vs. ㄸ), each letter has a different level of difficulty of recognition. ETDRS also has the same problem as it contains five letters per line, making it difficult to increase reproducibility. To minimize this problem, the letters in the Korean version of the MNREAD acuity chart were created by a linguist using second- and third-grade materials. Thus, our calculated reading acuity and the maximum reading speed (0.03 ± 0.10 and 174.4 ± 30.0 wpm, respectively) were similar to those of the English version of the MNREAD acuity chart (0.04 ± 0.11 and 153 ± 24 wpm). However, the calculated critical print size was better than that of the English version but identical to the Persian version (English version, 0.35; Persian version; − 0.068 and 0.056). This difference could result from the different shapes and compositions of letters in the Korean version (Table 2).

The maximum reading speed was around 174 wpm. The average reading speed was around 200–210 in English version and around 190 in Turkish version. The reason of the difference of reading speed is thought to be that Hangul has words with three consonants. Unfortunately, in the present study, the maximum reading speed was not the same for different people. Maximum reading speed varied depending on the reading tendency of each person. According to the instructions, reading as fast as possible was a rule. Nevertheless, because some people read rather slowly and some read very fast, the differences in reading propensity could not be ignored. Differences in maximum reading speed have also been reported in other studies9,12.

This study had some limitations. We did not compare the changes in the maximum reading speed, critical print size, or reading acuity in patients with low vision or old patients. Even normal people show differences according to age, so care should be taken in interpretation11. Therefore, further research is needed on comparing normal people and patients with low vision using the Korean version of the MNREAD acuity chart. The most important part is the consistency of each sentence13, and other Turkish or Greek versions were produced based on conditions similar to this study. In this study, sentences of second and third grade primary school were selected, and although the pattern is consistent to some extent as shown in Fig. 3, further research is needed on the reading ability between these sentences. Finally, we did not investigate the reading accessibility index because the number of subjects was not large enough to determine the parameter corresponding to the denominator of the formula6. In the future, we plan to establish a reference point of reading accessibility index through large-scale research.

In conclusion, the Korean version of the MNREAD acuity chart shows similar results to the existing chart. Therefore, this chart is expected to be useful for measuring the reading ability of Korean patients and for treatment evaluation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as they are not digital data; however, they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hilal, A., Bazarah, M. & Kapoula, Z. Benefits of implementing eye-movement training in the rehabilitation of patients with age-related macular degeneration: A review. Brain Sci. 12, 36 (2021).

Ikeda, M. C. et al. Interventions to improve reading performance in glaucoma. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 4, 624–631 (2021).

Xiong, Y. Z., Lei, Q., Calabrese, A. & Legge, G. E. Simulating visibility and reading performance in low vision. Front. Neurosci. 15, 671121 (2021).

Radner, W. Reading charts in ophthalmology. Graefes. Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 255, 1465–1482 (2017).

Mansfield, J.S., Ahn, S.J., Legge, G.E., Luebker, A. A new reading-acuity chart for normal and low vision. Noninvasive assessment of the visual system, NSuD.3. (Optica Publishing Group, 1993).

Calabrese, A., Owsley, C., McGwin, G. & Legge, G. E. Development of a reading accessibility index using the MNREAD acuity chart. JAMA Ophthalmol. 134, 398–405 (2016).

Sung, Y., Kwon, H. J., Choi, S. W. & Song, W. K. Development of a novel Korean reading chart. Clin. Exp. Optom. 105, 281–286 (2022).

Elham, R. & Jafarzadepur, E. Development and validation of the Persian version of the MNREAD acuity chart. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 32, 274–280 (2020).

İdil, ŞA. ÇALIŞKAN D, İDİL NB: Development and validation of the Turkish version of the MNREAD visual acuity charts. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 41, 565–570 (2011).

Castro, C. T., Kallie, C. S. & Salomao, S. R. Development and validation of the MNREAD reading acuity chart in Portuguese. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 68, 777–783 (2005).

Calabrese, A. et al. Baseline MNREAD measures for normally sighted subjects from childhood to old age. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57, 3836–3843 (2016).

Rhiu, S., Kim, M., Kim, J. H., Lee, H. J. & Lim, T. H. Korean version self-testing application for reading speed. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 31, 202–208 (2017).

Mansfield, J. S., Atilgan, N., Lewis, A. M. & Legge, G. E. Extending the MNREAD sentence corpus: Computer-generated sentences for measuring visual performance in reading. Vision Res. 158, 11–18 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We give our special thanks to Gordon E. Legge and J. Stephen Mansfield who generously helped with producing the Korean version of MNREAD acuity chart.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work."

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, U.S., Kim, K.S. & Kim, YS. Korean version of the MNREAD acuity chart. Sci Rep 14, 7429 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57717-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57717-4

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.