Abstract

This study aimed to identify the risk factors for placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) in women who had at least one previous cesarean delivery and a placenta previa or low-lying. The PACCRETA prospective population-based study took place in 12 regional perinatal networks from 2013 through 2015. All women with one or more prior cesareans and a placenta previa or low lying were included. Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) was diagnosed at delivery according to standardized clinical and histological criteria. Of the 520,114 deliveries, 396 fulfilled inclusion criteria; 108 were classified with PAS at delivery. Combining the number of prior cesareans and the placental location yielded a rate ranging from 5% for one prior cesarean combined with a posterior low-lying placenta to 63% for three or more prior cesareans combined with placenta previa. The factors independently associated with PAS disorders were BMI ≥ 30, previous uterine surgery, previous postpartum hemorrhage, a higher number of prior cesareans, and a placenta previa. Finally, in this high-risk population, the rate of PAS disorders varies greatly, not only with the number of prior cesareans but also with the exact placental location and some of the women's individual characteristics. Risk stratification is thus possible in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) is characterized histologically by the total or partial absence of decidua and placental invasion into the myometrium1,2. PAS has become a leading cause of peripartum hysterectomy and is associated with major maternal morbidity and even maternal death worldwide3,4.

Maternal mortality and morbidity are lower in women with PAS disorders who deliver in a referral center with a multidisciplinary care team experienced in managing the surgical risks and perioperative challenges that these disorders present5,6,7,8,9. Transfer to a referral center, however, requires both recognition of the women at risk of PAS and accurate prenatal diagnosis. Although routine imaging examinations have improved PAS screening during pregnancy, their performance is not yet good enough to reliably detect or rule out all cases. Risk stratification based on clinical indicators would thus be useful in helping to identify subgroups of women at very high risk.

Overall, 30 to 65% of PAS cases occur in women with at least one prior cesarean and a placenta previa or low-lying10,11,12. The combination of these two factors has been identified as a profile at high risk for PAS, and prenatal screening for these disorders is usually performed among this subgroup of women, rather than among all pregnant women12.

A few studies have analyzed the risk factors for PAS specifically in women with this high-risk profile13,14,15,16. They have found that among women with prior cesareans and placenta previa the risk of PAS increases with the number of previous cesareans. These studies were limited, however, by their center-based design with women included who may not have been representative of the general population. They also did not explore other possible PAS risk factors, most importantly, precise placenta location, but also individual characteristics and details of obstetric history, although this information could provide additional tools to stratify the risk of PAS among these women.

This prospective population-based study was designed to include all women with any prior cesarean deliveries and a placenta previa or low lying17. Our objective was to apply a population-based approach to investigate the risk factors, particularly the precise placenta location, for PAS in women with this profile.

Material and methods

This study took place in 176 French maternity units and hospitals belonging to 12 regional perinatal networks over a two-year period, from November 1, 2013, to October 31, 2015. It had a source population of 520 114 deliveries, 30% of the national total; the characteristics of the women giving birth were similar to those nationwide (Table S.1)18.

Recruitment and data collection started only after informed consent has been obtained from the participants of this study. The appropriate ethics committees approved this study.

The study protocol has previously been described17. In brief, all women with at least one previous cesarean section and a placenta previa or low-lying (0–20 mm from the internal cervical os, considered posterior if predominantly posterior or anterior if predominantly anterior), diagnosed by the last ultrasound before delivery-were included in the immediate postpartum period (i.e., a live or stillborn baby after 22 weeks of gestation). Placentas previa were considered as a single category, regardless of the predominant position of the placenta. First-, second-, and third-trimester ultrasound examinations are free of charge and part of routine care in France. Therefore nearly all pregnant women have all three scans; when a placenta is found to be previa or low lying, a transvaginal ultrasound is generally performed before delivery, in accordance with French recommendations18.

All women meeting the inclusion criteria were identified and flagged by local coordinators at each participating center. Moreover, the exhaustiveness of the case identification was verified by clinical research midwives, who consulted the delivery logbook and the computerized databases at each center. All women were followed up until their post-delivery discharge, and those with PAS until 6 months postpartum.

PAS was defined by the presence of at least one of the following clinical or histological criteria:17 (1) manual removal of the placenta partially or totally impossible and no cleavage plane between part or all of the placenta and the uterus; (2) massive bleeding from the implantation site after forced placental removal in the absence of another cause of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH); (3) histological confirmation of PAS on a hysterectomy specimen; (4) sign of PAS at laparotomy corresponding to the Grade 2 (increta type of abnormally invasive placenta) and 3 (percreta type of abnormally invasive placenta) clinical criteria of the FIGO classification19.

Research midwives manually reviewed the medical files to collect the following information: (1) maternal characteristics and medical history, including the women's age, geographical origin, medical insurance coverage, smoking status during pregnancy, body mass index, pre-existing diabetes or hypertension, gravidity, parity and any history of the following: PPH, manual removal of a placenta, termination of pregnancy, uterine surgery (myomectomy, hysteroscopy, or curettage), and cesarean delivery; (2) characteristics of the current pregnancy, including use of in vitro fertilization (IVF), type of pregnancy (singleton or multiple), pregnancy complications (second- or third-trimester bleeding, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia or preterm premature rupture of the membranes), and placental location.

Statistical analysis

The population-based incidence of women with a placenta previa or low lying and at least one prior cesarean was calculated with its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Characteristics of women, pregnancies, deliveries and pregnancy outcomes were described and compared between women with and without PAS. Categorical variables were compared with Pearson's Chi2 test or Fisher's exact test, and quantitative variables with Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon's rank-sum test, as appropriate.

Risk factors for PAS were identified by univariate and multivariable logistic regression modelling. Variables included in the multivariable model were selected based on the available literature and the results of the univariate analysis. We used multilevel modelling to take the correlation between observations within perinatal networks into account. The proportion of women with missing data for any covariate included in the multivariable model ranged from 0–8%; 333 (84%) women had no missing data. Missing data were considered missing at random. We imputed them by chained equations and computed 30 imputation datasets.

We used Stata/SE 15.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) to analyze the data.

Ethical approval

The appropriate ethics committees (Consultative Committee on the Treatment of Data on Personal Health for Research Purposes—reference n° AOR12156; 12/ 19/2013 , and the Committee for the Protection of People Participating in Biomedical Research—reference CPP 13-017; 05/28/2013) , and the National Data Protection Authority (CNIL n° DR-2013-427; 12/20/2013) approved the study.

Results

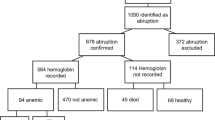

Of the 520 114 women who gave birth, 396 (0.76‰; 95% CI 0.69–0.84) had at least one prior cesarean delivery and a placenta previa or low-lying. Among them, 108 (27%; 95% CI 23–32) had PAS. Table S.2 shows the distribution of the PAS criteria: 83% of PAS cases met more than one of these criteria.

Women with PAS more often had a BMI≧30, higher gravidity and parity, a previous PPH, a previous PAS disorder, more prior cesareans, previous uterine surgery excluding cesareans, and more frequent previa locations of the placenta (Table 1).

The PAS rates in women with one, two, and three or more prior cesareans were respectively, 19% (95% CI 14–24), 36% (95% CI 25–48), and 57% (95% CI 43–71). PAS rates by placental position were 9% (95% CI 3–19) when it was posterior low lying, 21% (95% CI 12–33) when anterior low lying, and 33% (95% CI 28–39) when previa (Table 2). Combining the number of prior cesareans and the location of the placenta yielded a PAS rate ranging from 5% (95% CI 1–15) for one prior cesarean combined with a posterior low-lying placenta, to 63% (95% CI 45–79) for three or more prior cesareans combined with placenta previa (Table 2).

In the multivariable analysis, the risk factors for PAS among these women with any prior cesarean delivery and an abnormally located placenta were BMI ≧ 30, previous uterine surgery, previous PPH, more prior cesareans and placenta previa (Table 3). The rate of PAS was 2% (95% CI 0–11) in women without any of these four risk factors and 31% (95% CI 26–36) in women with at least one.

Discussion

About one quarter of the women with any prior cesareans and a placenta previa or low lying had PAS. Risk factors for these disorders in this population were BMI ≧ 30, previous uterine surgery, previous PPH, prior cesareans (risk increasing with number), and placenta previa versus low-lying.

The 27% PAS rate among this high-risk profile population contrasts with the proportion of 5 to 10% reported in two previous population-based studies10,11. Potential explanations for this difference may be related to the fact that those two studies did not collect the total number of women with abnormally located placentas specifically for the study, as we did, but instead derived it from routine databases where diagnoses may be less accurately reported. They may also have included in their denominator previa or low-lying placentas in the second but not the third trimester and women with prenatal bleeding from other causes10,11.

Several previous studies have explored PAS risk factors. Most were conducted in general populations of pregnant women and compared women with and without PAS. One or more prior cesareans and an abnormally located placenta are both present in approximately half the cases of PAS, and their combination has been recognized as a major risk factor10,11,13,14,15,16. These findings have guided current clinical practice to focus PAS screening in the subgroup of women combining these conditions. However, the characteristics of women with PAS have been shown to differ between those with the combination of at least one prior cesarean and an abnormally located placenta and those without both12,20. Risk factors for PAS may therefore be specific to each of these two subgroups and should be explored separately. No previous study has specifically assessed the risk factors for PAS among women with any prior cesareans and placenta previa or low-lying.

We found that the risk of PAS increases not only with the number of prior cesareans but also varies with the placenta location relative to the internal cervical os: despite findings about the risk of PAS and the number of previous cesareans, no study had explored the risk according to the placenta location14. Posterior low-lying placenta are generally not implanted on the cesarean scar which may explain the lower risk of PAS. The position of the previous uterine cesarean scar (or scars) may explain the higher risk of PAS in women with placenta previa compared with low-lying locations. Cesarean scars are located in the anterior uterine wall, close to the internal os, or in the cervix; their precise position depends on cervical dilation at the time of the previous cesareans21. In an ongoing pregnancy with a previous cesarean, the scar is located in the cervix in 50 to 75% of cases22.

We found higher BMI to be associated with a higher risk of PAS in women with prior cesareans and placenta previa or low-lying. The growing proportion of pregnant women who are obese may thus contribute to the increasing rate of PAS disorders, along with rising cesarean rates23,24. This association is found inconsistently in the literature in the general population and had never been studied within the high risk population of women with any prior cesareans and placenta previa or low-lying10,11. Obesity may contribute to abnormal decasualization through various mechanisms involving hormonal balance and the effects of endometrial free fatty acid accumulation and lipotoxicity25.

PAS was also more frequent in women with previous PPH, which may be a cause or a marker of decidualization failure and has been associated with PAS in general populations of parturients11,26. Our study shows, interestingly, that even among women with a prior cesarean and placenta previa or low-lying, previous PPH is associated with an increased risk of PAS.

Strengths of our study include its large size, its population-based design with a rigorous verification of case ascertainment completeness, and especially its focus on women with the two best-known determinants of PAS, which provides a clinically relevant population. Another strength, in contrast with previous studies13,14,15,16, is the precise analysis of the placenta location and the availability of detailed data regarding the distance between the placental edge and the internal cervical os.

Contrary to other studies, we did not find any association of IVF with PAS in our study27,28,29,30. However, previous studies who reported an increased risk of PAS in women with IVF were mostly conducted in a general population of pregnant women, whereas our study was focused on the specific population of women with a placenta previa and a previous cesarean31. An important point is that IVF is associated with a higher risk of placenta previa which itself is a major risk factor of PAS30. Therefore, the increased risk of PAS in cases of IVF is likely, at least in part, mediated by the increased risk of placenta previa, but that, among women with previa and previous cesarean, having or not having had an IVF does not make a difference in terms of PAS risk. Further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The specific identification of risk factors for PAS in women with any prior cesareans and an abnormally located placenta may be useful for pinpointing women at particularly high risk of PAS to customize the information they receive as well as their care during pregnancy and delivery.

This study suggests a pathophysiological hypothesis related to abnormal decidualization that should be investigated to find specific targets for preventing PAS disorders. In addition, in women with any prior cesareans and an abnormally located placenta, a next step would be to test the predictive performance of combining the clinical risk factors identified here and imaging features in a single score.

One potential limitation is the absence of histologic confirmation of PAS for the cases without hysterectomies. The prospective design and prespecified definitions make the risk of false diagnosis of PAS low. Another potential limitation is that the number of women with a posterior low-lying placenta may have been underestimated if some that were asymptomatic were not identified. That could overestimate the prevalence of PAS among this subgroup but is unlikely to bias the risk factors of PAS identified.

Finally, the rate of PAS disorders varies greatly not only with the number of prior cesareans but also with the precise location of the placenta and some of the women's individual characteristics. The specific identification of risk factors for PAS in women with any prior cesareans and a placenta previa or low lying will help to pinpoint women at particularly high risk of PAS to customize the information they receive as well as their care during pregnancy and delivery.

Data availability

Data are available if requested to Gilles Kayem after acceptance by our institution.

References

Khong, T. Y. & Robertson, W. B. Placenta creta and placenta praevia creta. Placenta 8, 399–409 (1987).

Jauniaux, E. & Jurkovic, D. Placenta accreta: Pathogenesis of a 20th century iatrogenic uterine disease. Placenta 33, 244–251 (2012).

van den Akker, T., Brobbel, C., Dekkers, O. M. & Bloemenkamp, K. W. Prevalence, indications, risk indicators, and outcomes of emergency peripartum hysterectomy worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 128, 1281–1294 (2016).

Saucedo, M., Deneux-Tharaux, C. & Bouvier-Colle, M. H. Ten years of confidential inquiries into maternal deaths in France, 1998–2007. Obstet. Gynecol. 122, 752–760 (2013).

Eller, A. G. et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet. Gynecol. 117, 331–337 (2011).

Shamshirsaz, A. A. et al. Multidisciplinary team learning in the management of the morbidly adherent placenta: Outcome improvements over time. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 216, 612.e1–12.e5 (2017).

Al-Khan, A. et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes in placenta accreta after institution of team-managed care. Reprod. Sci. 21, 761–771 (2014).

Silver, R. M. et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 212, 561–568 (2015).

Erfani, H. et al. Maternal outcomes in unexpected placenta accreta spectrum disorders: single-center experience with a multidisciplinary team. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 221(337), e1-37 (2019).

Fitzpatrick, K. E. et al. Incidence and risk factors for placenta accreta/increta/percreta in the UK: A national case-control study. PLoS ONE 7, e52893 (2012).

Thurn, L. et al. Abnormally invasive placenta-prevalence, risk factors and antenatal suspicion: Results from a large population-based pregnancy cohort study in the Nordic countries. BJOG 123, 1348–1355 (2016).

Kayem, G. et al. Clinical profiles of placenta accreta spectrum: The PACCRETA population-based study. BJOG 128, 1646 (2021).

Miller, D. A., Chollet, J. A. & Goodwin, T. M. Clinical risk factors for placenta previa-placenta accreta. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 177, 210–214 (1997).

Silver, R. M. et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet. Gynecol. 107, 1226–1232 (2006).

Bowman, Z. S. et al. Risk factors for placenta accreta: A large prospective cohort. Am. J. Perinatol. 31, 799–804 (2014).

Clark, S. L., Koonings, P. P. & Phelan, J. P. Placenta previa/accreta and prior cesarean section. Obstet. Gynecol. 66, 89–92 (1985).

Kayem, G., Deneux-Tharaux, C., Sentilhes, L. & Group, P. PACCRETA: Clinical situations at high risk of placenta ACCRETA/percreta: Impact of diagnostic methods and management on maternal morbidity. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 92, 476–82 (2013).

Enquête nationale périnatale (2016), Paris, France, http://www.epope-inserm.fr/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/ENP2016_rapport_complet.pdf. Paris, France, http://www.epope-inserm.fr/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/ENP2016_rapport_complet.pdf., 2016 (vol 2019).

Jauniaux, E., Ayres-de-Campos, D., Langhoff-Roos, J., Fox, K. A. & Collins, S. FIGO classification for the clinical diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 146, 20–24 (2019).

Hessami, K. et al. Clinical correlates of placenta accreta spectrum disorder depending on the presence or absence of placenta previa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 140, 599–606 (2022).

Kamel, R., Eissa, T., Sharaf, M., Negm, S. & Thilaganathan, B. Position and integrity of uterine scar are determined by degree of cervical dilatation at time of Cesarean section. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 57, 466–470 (2021).

Markovitch, O., Tepper, R. & Hershkovitz, R. Sonographic assessment of post-cesarean section uterine scar in pregnant women. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 26, 173–175 (2013).

Fisher, S. C., Kim, S. Y., Sharma, A. J., Rochat, R. & Morrow, B. Is obesity still increasing among pregnant women? Prepregnancy obesity trends in 20 states, 2003–2009. Prev. Med. 56, 372–378 (2013).

Heslehurst, N. et al. Trends in maternal obesity incidence rates, demographic predictors, and health inequalities in 36,821 women over a 15-year period. Bjog 114, 187–194 (2007).

Rhee, J. S. et al. Diet-induced obesity impairs endometrial stromal cell decidualization: A potential role for impaired autophagy. Hum. Reprod. 31, 1315–1326 (2016).

Eshkoli, T., Weintraub, A. Y., Sergienko, R. & Sheiner, E. Placenta accreta: Risk factors, perinatal outcomes, and consequences for subsequent births. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 208(219), e1-7 (2013).

Nagata, C. et al. Complications and adverse outcomes in pregnancy and childbirth among women who conceived by assisted reproductive technologies: A nationwide birth cohort study of Japan environment and children’s study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 77 (2019).

Tanaka, H. et al. Evaluation of maternal and neonatal outcomes of assisted reproduction technology: A retrospective cohort study. Medicina (Kaunas) 56, 3255 (2020).

Zhu, L. et al. Maternal and live-birth outcomes of pregnancies following assisted reproductive technology: A retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 6, 35141 (2016).

Carusi, D. A., Gopal, D., Cabral, H. J., Racowsky, C. & Stern, J. E. A risk factor profile for placenta accreta spectrum in pregnancies conceived with assisted reproductive technology. F S Rep. 4, 279–285 (2023).

Matsuzaki, S. et al. Antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum after in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 11, 9205 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the URC-CIC Paris Descartes Necker/Cochin (Laurence Lecomte) for the study implementation, monitoring, and data management; the coordinators of the participating regional perinatal networks for their help in the implementation and coordination of the PACCRETA Study in their region: Alsace, Aurore, Auvergne, Basse-Normandie, Centre, Lorraine, MYPA, NEF, Paris Nord, Pays de Loire, 92 Nord; Isabelle AVRIL, Sophie BAZIRE, Sophie BEDEL, Fanny DE MARCILLAC, Laurent GAUCHER, Maëlle GUITTON, Catherine GUERIN, Laurence LECOMTE, Marine PRANAL, Laetitia RAULT, Anne VIALLON, Myriam VIRLOUVET and Justine SCHWANKA, for their contribution to the women’s inclusion and data collection; the obstetricians, midwives, and anaesthetists who contributed to case identification and documentation in their hospitals; and the research assistants who collected the data. The authors also thank Jo Ann Cahn for editorial assistance.

Funding

PACCRETA was funded by the French Health Ministry under its Clinical Research Hospital Program (Grant Number: AOR12156) and by the Angers University Hospital. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. All methods were carried out by relevant guidelines and regulations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.K. designed the study, coordinated the data collection, conducted the validation of the data, participated in the analysis and wrote the paper. C.D. and L.S. participated in the study design, coordinated the data collection, conducted the validation of the data, participated in the analysis and contributed to writing the article. A.S. assisted with data collection, participated in the validation of the data, analysed the data and contributed to writing the article. C.C. assisted with data collection, participated in the validation of the data and contributed to writing the article. SP reviewed all the pathology reports. B.B., G.B., C.D., B.G., C.C.H., C.H., J.F., N.W., B.L., P.R., O.M., M.P.B., F.P., E.A., L.C., P.R., R.C.R., M.D., F.V., S.P. assisted with data collection and contributed to writing the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kayem, G., Seco, A., Vendittelli, F. et al. Risk factors for placenta accreta spectrum disorders in women with any prior cesarean and a placenta previa or low lying: a prospective population-based study. Sci Rep 14, 6564 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56964-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56964-9

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.