Abstract

Long-term demographic studies at biogeographic transition zones can elucidate how body size mediates disturbance responses. Focusing on subtropical reefs in eastern Australia, we examine trends in the size-structure of corals with contrasting life-histories and zoogeographies surrounding the 2016 coral bleaching event (2010–2019) to determine their resilience and recovery capacity. We document demographic shifts, with disproportionate declines in the number of small corals and long-term persistence of larger corals. The incidence of bleaching (Pocillopora, Turbinaria) and partial mortality (Acropora, Pocillopora) increased with coral size, and bleached corals had greater risk of partial mortality. While endemic Pocillopora experienced marked declines, decadal stability of Turbinaria despite bleaching, coupled with abundance increase and bleaching resistance in Acropora indicate remarkable resilience of these taxa in the subtropics. Declines in the number of small corals and variable associations with environmental drivers indicate bottlenecks to recovery mediated by inhibitory effects of thermal extremes for Pocillopora (heat stress) and Acropora (heat and cold stress), and stimulatory effects of chlorophyll-a for Turbinaria. Although our study reveals signs of resilience, it foreshadows the vulnerability of subtropical corals to changing disturbance regimes that include marine heatwaves. Disparity in population dynamics suggest that subtropical reefs are ecologically distinct from tropical coral reefs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the global imprint of climate change on natural systems intensifies and environmental conditions are becoming more stressful for many species, demographic approaches are increasingly used to assess the effects of environmental disturbances on the short- and long-term population dynamics of plants and animals1. Species respond differently to disturbance, and interspecific and size-dependent variation in demographic performance can provide valuable insights into the mechanisms that underly persistence in different habitats and the idiosyncratic effects of environmental stress2. Long-term demographic studies are thus urgently needed to determine taxon-specific responses to disturbance3, their recovery capacity4 and ultimately to anticipate future community reorganisation under climate change1.

Climate change is exacerbating environmental extremes5 that often lead to unexpected consequences6. Hence, much can be learned from studies of populations that naturally persist in extreme settings7,8,9. Classical demographic theory predicts that natural selection maximises the long-term growth rate of populations in fluctuating environments10. Yet, depending on their life history traits, some taxa exploit short-term demographic strategies (e.g., ability to rapidly enhance population growth) to persist in highly variable and extreme environments11. Besides, just like species vary in their responses to disturbance, conspecific individuals of different sizes or developmental stages often respond differently to disturbance, thereby influencing population dynamics and demographic resilience1. Long-term decadal-scale demographic monitoring is therefore critical to determine recovery trajectories of different species in response to environmental stress, especially for long lived taxa with diverse life histories such as corals12 and trees13.

Recent evidence suggests that climate-driven disturbances such as drought and marine heatwaves alter size-dependent patterns in mortality, with lasting impacts on recovery capacity13,14. Shifts in the size structure of species with contrasting life histories can reflect distinct demographic drivers4 and when linked with environmental data can reveal vulnerabilities of distinct life stages to environmental stress15,16. Size-based demographic approaches thus provide valuable insights into the potential mechanisms that influence recovery trajectories following disturbance4,12,17, such as the existence of recruitment bottlenecks18 and post-settlement mortality19. For instance, on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), declines in the number of small corals20 and impaired stock-recruitment dynamics have diminished recovery capacity in the years directly following mass coral bleaching in response to heat stress18.

Abiotic stress is especially pronounced where species occur at the limits of their geographic distribution and environmental tolerances 8,21. As such, subtropical reefs south of the GBR present the ideal system in which to investigate decadal-scale population dynamics of corals in naturally variable and stressful conditions. With above-average observed and projected warming, this region is considered a warming hotspot22. Yet, despite tropicalisation of fish assemblages and declines in temperate seaweeds6, coral assemblages have remained relatively stable between 1990 and 2013/201423. They subsequently suffered extensive coral bleaching in 201616,24,25 and the extent to which the abundance and size structure of different species have recovered to pre-disturbance trajectories is still unknown but critical for determining their resilience to changing conditions. Moreover, as corals are colonial organisms that can exhibit partial mortality, investigating size-dependent patterns in partial mortality and coral bleaching can provide valuable insights into population dynamics and susceptibilities of different life stages to disturbance12.

Here, we quantify decadal patterns in the population size structure of corals in the Solitary Islands Marine Park (30° South) between 2010 and 2019, surrounding the pantropical coral bleaching event of 2016. Specifically, to determine their resilience and recovery potential following heat stress we examine spatio-temporal patterns in the population size-structure of three coral genera with contrasting life-histories and distributions before, during and after coral bleaching. On the Great Barrier Reef, juveniles of most examined coral taxa were more resistant to bleaching than adult corals26. Therefore, to test whether corals in high-latitude settings undergo similar size dependency in disturbance responses, we examine whether coral bleaching and partial mortality vary among taxa and are influenced by coral size. Given the importance of population replenishment for recovery and evidence of recruitment limitation in subtropical ecosystems16,27,28,29, we quantify environmental correlates of juvenile coral abundances to determine potential abiotic drivers of recovery dynamics in the subtropics. Consistent with trait-based filtering30 and different range limiting factors21, we expect that demographic patterns and environmental drivers vary among species and that coral abundance has declined during the 10-year period surrounding the 2016 coral bleaching event. Our study on the long-term population trajectories of different species following heat stress is key to predicting future trajectories of high-latitude reefs in warming seas.

Methods

Survey design and data collection

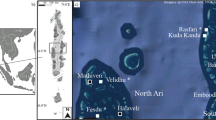

Coral surveys were conducted at four sites in the Solitary Islands Marine Park (30° South) in subtropical eastern Australia between 2010 and 2019. In this region corals persist in cool, light-limited, nutrient-rich and highly variable conditions21 and grow directly on rocky substrate. Coral communities exist in pockets of suitable rocky habitat31 and are considered marginal and extreme8 for most corals. Considering known cross-shelf gradients in biotic communities and environmental conditions in the region30,31,32 we surveyed two inshore (Southwest and Northwest Solitary Islands, 2–6 km from shore) and two offshore (South and North Solitary Islands, 6–11 km from shore) sites located on the semi-protected leeward side of islands (see Appendix Fig. A.1). The four sites were surveyed during the Austral spring of 2010, 2012, 2016, 2018 and 2019, and during a coral bleaching event in April 2016 to monitor temporal change in coral assemblages. As surveys weren’t conducted annually during this period and to investigate the effect of the 2016 bleaching event on coral populations, we grouped the surveys into 3 periods that accounted for the gap in survey years between periods. Specifically, we grouped surveys into Period 1 (2010, 2012), characterising the pre-bleaching state; Period 2 (April and October 2016), encapsulating the bleaching event and immediate aftermath; and Period 3 (2018, 2019), which is long enough after the disturbance to begin to track recovery (i.e., 2–3 years of possible recruitment).

At each site, we ran 3 replicate, 30 m long by 1.2 m wide photographic belt transects at 8-10 m depth, taking 30 downward-facing non-overlapping photos of 1 m × 1.2 m size per transect, capturing a total area of 108 m2 across the 3 transects (36 m2 per transect) per site. On each visit, transects were haphazardly placed running from an initial marker in the spatially restricted coral habitat (i.e., hundreds of meters), were at least 20 m apart and representative of the study sites30. An L-shaped calibration stick was used to maintain consistent vertical distance (80 cm) above the substrate and to include a scale of known size in the photographs for measurements of planar area (see Figure 1 in33). Sizes of individual corals in the genera Acropora, Pocillopora and Turbinaria were extracted from photographs using the SizeExtractR workflow in ImageJ and R33, recording the genus, and the incidence of bleaching (0 = not bleached, 1 = bleached) and partial mortality (0 = without partial mortality, 1 = with partial mortality) for each coral. Bleaching status and partial mortality were visually assessed from photographs by recording whether a coral had whitened relative to the typical colouration of unbleached Acropora, Pocillopora and Turbinaria corals at the sites, and whether the coral contained dead parts devoid of living tissue, respectively. We chose the three genera due to their high abundance in the region (i.e., up to 70% of Scleractinia abundance30) and to determine whether patterns of abundance and population size structure varied among taxa with different distributions and traits: the subtropical endemic Pocillopora aliciae, a brooding coral of branching morphology that only occurs in coastal New South Wales (NSW); hermaphroditic, broadcast spawning, predominantly tabular Acropora with a tropical-subtropical distribution; and gonochoric, broadcast spawning Turbinaria of laminar morphology with a predominantly subtropical distribution.

Although individual corals were not followed through time, we likely captured many of the same coral colonies in our repeat surveys as transects were placed in the same area on each visit to limit within-site variability. To ensure consistent capture of small corals across surveys, we applied a lower size cut-off of 0.8 cm2 (~ 1 cm diameter), excluding all corals < 0.8 cm2 from data analysis. 10.7% of coral colonies were not fully captured in the photographs and we were only able to outline the perimeter of the colony area visible in the photographs for these corals as information from outside the photographs was unavailable. To ensure that the underestimated sizes of these partially captured colonies did not affect our results we performed analyses with and without partially captured colonies. As we found no qualitative difference in the results and because the inclusion of partially captured colonies provides more accurate estimates of coral abundance, all analyses in the main manuscript include partially captured colonies. Complementary analyses that exclude partially out of frame corals can be found in Appendix A and show that sub-setting of the data did not alter the main findings.

Environmental data

The physical and chemical oceanography of this region is strongly influenced by the warm poleward flowing East Australian Current (EAC), with greater EAC influence at offshore islands where temperatures are approximately 1 °C higher32 and chlorophyll a concentrations are lower than at inshore sites34. EAC waters are generally more oligotrophic and have lower chlorophyll a concentrations than adjacent Tasman Sea Water35, also affecting light penetration and water clarity. To characterise environmental conditions at the study sites and examine their influence on coral population replenishment, we compiled daily sea surface temperature data (SST) from the global 5 km resolution NOAA Coral Reef Watch CoralTemp reanalysis36 and daily chlorophyll a (Chla) data at 9 km resolution from NASA OceanColour37 as a proxy for nutrient content. Temporal gaps in the Chla record were filled using linear interpolation. We calculated mean annual SST (SST_mean) and Chla (Chla_mean) for each site and year, as well as three thermal stress metrics to examine the role of heat and cold stress. Specifically, we calculated Degree Heating Weeks (DHW0C) as the accumulated weekly temperature anomalies (daily data divided by 7 to move from days to weeks) over the previous 12 weeks (i.e., 84 days inclusive) that exceed the long-term maximum of monthly means climatology (MMM) to account for the accumulation of low-level heat stress following16,24,38. This means that the absolute values of DHW0C are greater than the conventional NOAA Coral Reef Watch metric that accumulates thermal anomies greater than 1 °C above the MMM24,36,38. Analogous to this definition, we calculated Degree Cooling Weeks (DCW) as the accumulation of values below the long-term minimum of monthly means (mMM) over the preceding 12-week period39, whereby larger negative values indicate higher accumulated cold stress (DCW0C). As cold stress is an important predictor of coral biodiversity patterns in this21 and other high-latitude regions40,41, we computed a second DCW metric with a higher temperature threshold to assess the potential effect of very low magnitude cold stress at the poleward range-limit of corals (DCW1C). In the computation of DCW1C cold stress starts accumulating once SST reaches a threshold of 1 °C above the mMM (i.e., once SST is colder than mMM + 1 °C).

Data analyses.

Taxonomic, spatial and temporal trends in colony size structure

To examine spatiotemporal trends in the colony size structure of corals with contrasting life histories we constructed size-frequency distributions for Acropora, Pocillopora and Turbinaria corals based on log-transformed colony area. We used 2-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests to examine whether size-frequency distributions varied among taxa, periods and between inshore and offshore sites.

To further characterise size-based patterns, we divided colony counts into five size classes (quintiles), which we grouped into small (1st quintile), medium-sized (2nd to 4th quintile) and large (5th quintile) corals following Dietzel, et al.20. The abundance of small corals is a proxy for population replenishment, encompassing variation in both settlement and post-settlement survival and the abundance of large corals can characterise reproductive output. As population size structure tends to vary among taxa and habitats42, the boundaries between size bins were allowed to vary among taxa and habitats (i.e., inshore, offshore), but fixed across years. We also calculated mean colony size, coefficient of variation, skewness, and the 1st and 5th quintiles of colony size. The coefficient of variation (CV = σ⁄μ) is a standardised measure of the dispersion of size-frequency distributions suited to comparing populations with different mean colony sizes. Skewness measures asymmetry of size-frequency distributions and reflects the proportion of small versus large colonies, whereby positive and negative skewness indicate a high proportion of small and large corals, respectively42.

To characterise spatial and temporal trends in the colony size structure of Acropora, Pocillopora and Turbinaria corals in detail, we calculated changes in the abundance of small (1st quintile), medium (2nd to 4th quintile) and large (5th quintile) corals at inshore and offshore sites between periods 1 (2010, 2012) and 3 (2018, 2019) following Dietzel, et al.20. We also determined changes in the mean and CV of colony size, and of the 1st and 5th quintile of the colony size structure to assess changes in the size of the smallest (bottom 20%) and largest (top 20%) corals in the population, respectively. Specifically, an increase in the 1st quintile indicates that corals in the bottom 20% were larger due to a decline in the relative abundance of small corals. An increase in the 5th quintile indicates a size increase of corals in the 80th percentile due to an increase in the relative abundance of large corals. We used bootstrap resampling (n = 1000) from posterior distributions to characterise uncertainties in size-class abundances and report parameter uncertainties as 66% and 95% highest posterior density intervals.

We used Bayesian generalised linear models (GLMs) to assess the interactive effects of period, shelf position and taxa (~ period * position * taxa) on trends in mean coral size (family = gaussian) and coral abundance (family = log link negative binomial) pooled across transects. We then used Bayesian binary logistic regression (family = bernoulli) to assess the effects of coral size (logArea) and taxon on whether corals bleached (bleaching ~ logArea * taxa) or experienced partial mortality (partial mortality ~ logArea * taxa) and to determine whether the odds of corals suffering partial mortality varied among periods and taxa (partial mortality ~ period * taxa). We also tested whether bleached corals had greater odds of suffering partial mortality than unbleached corals (partial mortality ~ bleaching; family = bernoulli).

Environmental correlates of patterns in the abundance of small corals

The recruitment of new individuals is key to population recovery after disturbance, and in open marine populations, captures both pre- and post-settlement processes43. In coral surveys, the abundance of small corals is frequently used as a proxy for recruitment19,20,44 encapsulating processes not directly measured in the surveys that can affect recovery, such as larval supply, settlement rates and post-settlement survivorship43,45. To investigate how abiotic conditions might be influencing population replenishment on subtropical reefs, we therefore fit Bayesian GLMs with a log link negative binomial variance structure to examine the environmental predictors (see Table A.3. for predictors in the models) that best explained spatiotemporal trends in the abundance of small Acropora, Turbinaria and Pocillopora corals as a proxy for recruitment. Notably, small colonies can also come about thorough partial mortality, however, the incidence of partial mortality was low in our study. Due to multi-collinearity (r > 0.8, Appendix Table A.2), the DCW1C metric was used in the models to assess the effect of cold stress. We calculated Bayes R2 values and used approximate leave-one-out cross-validation with LOO information criterion (LOOIC) to assess model fit and compare model weights (i.e., the relative likelihood of a model, based on the relative scaling of models in the model set).

All models were created using the probabilistic framework offered by Bayesian statistics and executed in Stan, accessed with the R package ‘brms’46. We chose a Bayesian approach as it (i) quantifies uncertainty by sampling from the posterior distributions, (ii) can account for asymmetrically distributed uncertainty distributions, and (iii) flexibly handles complex models that quantify uncertainty for all parameters46. We summarised model fits using the 95% highest posterior density interval as the credible interval and computed median point estimates for all chains. To improve convergence and guard against overfitting, we specified weakly informative conservative priors and ran each model with three chains of 4000 iterations (warmup = 200) and a thinning rate of 5. We examined chain mixing, performed posterior predictive checks to assess model fit, and used the Gelman–Rubin convergence diagnostic (R-hat) to assess model convergence.

Results

Patterns in coral size structure

We recorded a total of 13,195 coral colonies across 2160 images; 6992 Pocillopora, 3207 Turbinaria and 2996 Acropora, with Pocillopora more abundant offshore and Turbinaria more abundant inshore (Figs. 1 and 2, Table A.1). Size-frequency distributions varied markedly among taxa (Fig. 1), with Pocillopora and Turbinaria (2-sample KS test, D = 0.517, p < 0.001) most dissimilar, followed by Pocillopora and Acropora (D = 0.243, p < 0.001) and Acropora and Turbinaria (D = 0.112, p < 0.001) for all sites and years pooled. Log-transformed size-frequency distributions were negatively skewed for Turbinaria (− 0.29), indicating relatively fewer colonies in the smaller size classes and a dominance of large corals. Colony size structure of Pocillopora (− 0.03) and Acropora corals (0.05) was fairly symmetrical (i.e., skewness close to zero) when pooled for all sites and years (Appendix Table A.1).

Patterns in the (a) mean size and (b) number of Acropora, Pocillopora and Turbinaria corals at Inshore (red) and Offshore (blue) sites in the Solitary Islands Marine Park in Period 1 (2010, 2012), Period 2 (April and October 2016) and Period 3 (2018, 2019). Estimates are shown as 95% highest posterior density intervals with 95% upper and 95% lower credible intervals.

Size-frequency distributions varied significantly between inshore and offshore habitats for all genera (2-sample KS test, Turbinaria, D = 0.308, p < 0.001; Acropora D = 0.161, p < 0.001; Pocillopora, D = 0.125, p < 0.001), with higher densities of larger corals inshore (Fig. 1). Colony size varied most for Pocillopora (CV = 0.51) and least for Turbinaria corals (CV = 0.31, Appendix Table A.1). Size-frequency distributions changed over time for all taxa. Notably, over the duration of the study (i.e., Periods 1 vs. 3) temporal shifts were most pronounced for Pocillopora (Offshore D = 0.367, p < 0.001; Inshore D = 0.216, p < 0.001) and Acropora (Inshore D = 0.249, p < 0.001; Offshore D = 0.189, p < 001), with Turbinaria populations the most stable (Inshore D = 0.129, p < 0.001; Offshore D = 0.129, p = 0.74). Greatest shifts occurred between Periods 1 and 2 (Pocillopora, Offshore D = 0.4, p < 0.001, Inshore D = 0.15, p < 0.001; Acropora, Inshore D = 0.238, p < 0.001, Offshore D = 0.219, p < 0.001; Turbinaria Inshore D = 0.066, p = 0.023, Offshore D = 0.124, p = 0.765), with minor changes in size-frequency distributions between Periods 2 and 3 for Pocillopora (Inshore D = 0.099, p = 0.016; Offshore D = 0.059, p = 0.014) and Turbinaria Inshore (D = 0.084, p = 0.002).

Mean colony size varied among taxa and ranged between 66.42 cm2 for Pocillopora and 708.47 cm2 for Turbinaria and was larger inshore for all taxa during all time periods (Fig. 2, Appendix Table A.1). Colony size structure shifted towards larger colonies through time, as shown by increases in mean colony size for all taxa as well as increases in the size of small (in the 20th percentile) and large (in the 80th percentile) colonies and declines in the coefficient of variation (Fig. 3).

Changes in the mean, coefficient of variation (CV) and 20th and 80th percentile of the colony size structure of Acropora, Pocillopora and Turbinaria corals in the Solitary Islands Marine Park between Period 1 (2010, 2012) and Period 3 (2018, 2019). Percentiles are indicators for the relative abundance of the smallest (20th percentile) and largest (80th percentile) corals, where increases in the 20th and 80th percentiles indicate a decrease in the relative abundance of the smallest corals and an increase in the relative abundance of largest corals in the population, respectively. All estimates are shown as 95% highest posterior density intervals where the point indicates the median, the thick line the 66% credible interval and the thin line the 95% credible interval.

Patterns in coral abundance

The abundance of Pocillopora colonies declined through time, especially offshore, whereas the abundance of Turbinaria and Acropora remained relatively stable (Fig. 2b). The abundance of small corals declined for all taxa in all periods (Fig. 4). Although the abundance of medium and large corals followed a stable to upward trajectory up until 2016 (Periods 1 vs. 2), the abundance of medium and large corals declined considerably in the aftermath of coral bleaching (Period 2 vs. 3) for all taxa, except for slight increases in the abundance of large Turbinaria colonies (Fig. 4).

Changes in the abundance of small, medium, and large colonies for all taxa between Periods 1 versus 2, Periods 2 versus 3, and Periods 1 versus 3. Percentage changes in abundances are defined as changes in the number of corals in the 1st quintile (small), 2nd–4th quintile (medium) and 5th quintile (large) of colony size. All estimates are shown as 95% highest posterior density intervals. The point indicates the median, the thick line the 66% credible interval and the thin line the 95% credible interval.

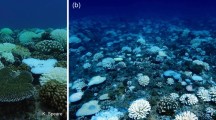

Patterns in coral bleaching and partial mortality

The incidence of coral bleaching varied among taxa, with the probability of bleaching highest for Pocillopora (0.806), followed by Turbinaria (0.653) and minimal bleaching of Acropora (0.069). Larger corals had a higher probability of bleaching (Fig. 5a), and this effect was greatest for Turbinaria, followed by Pocillopora and was not significant for Acropora (95% CI − 0.17, 0.20 overlapped zero).

Relationships between the size of Acropora (red), Pocillopora (blue), and Turbinaria (green) corals and the probability of suffering (a) coral bleaching and (b) partial mortality. (c) Temporal patterns in the probability of partial mortality for Period 1 (2010, 2012), Period 2 (April and October 2016) and Period 3 (2018, 2019). Estimates are shown as 95% highest posterior density intervals with 95% upper and 95% lower credible intervals.

Coral size also influenced whether a coral suffered partial mortality, with larger Acropora and Pocillopora corals exposed to greater odds of partial mortality (Fig. 5b). Acropora corals had the highest probability of suffering partial mortality across all periods (0.04 Period 1, 0.106 Period 2, 0.116 Period 3; Odds of 2.581 and 2.851 compared to 0.04 in Period 2), followed by Pocillopora (0.012 Period 1, 0.079 Period 2, 0.062 Period 3) and Turbinaria (0.014 Period 1, 0.0251 Period 2, 0.03 Period 3). The odds of suffering partial mortality were higher in Periods 2 and 3, compared to Period 1 for all taxa (but not significant for Turbinaria) (Fig. 5c). Bleached corals had a greater probability of partial mortality (0.0552) than unbleached (0.0183) corals (95% CI 1.62, 4.66).

Environmental correlates of patterns in the abundance of small corals

We found spatio-temporal variation in environmental conditions, with higher SST_mean and DHW0C offshore, and higher Chla_mean and DCW1C inshore (Figure A.3). Low-level heat and cold stress accumulated in all survey years, with highest heat stress (DHW0C = 7.54 °C weeks at North Solitary Island) in 2016 (i.e., the bleaching year) and highest cold stress (DCW1C = 13.52 °C weeks at Southwest Solitary Island) in 2012 (Figure A.3). Environmental predictors of the abundance of small corals varied among taxa (Fig. 6, Table A.3). Specifically, the abundance of small Acropora corals was best explained by patterns in thermal stress, with small corals more prevalent in areas (or times) of low heat (DHW0C) and cold stress (DCW1C). Small Pocillopora corals were more abundant where SST_mean was high and DHW0C was low. The abundance of small Turbinaria corals was independent of thermal stress and showed a positive association with Chla_mean (best model). The second-best model for Turbinaria indicated more small corals where SST_mean was low and Chla_mean was high (model weight = 0.2; Table A.3).

Relationships between the number of small corals and environmental conditions on subtropical reefs in the Solitary Islands Marine Park, eastern Australia, for (a) Pocillopora, (b) Acropora, and (c) Turbinaria corals. Plots show best models for results given in Supplementary Table A.3. Note that for Degree Cooling Weeks, larger negative values indicate higher accumulated cold stress. Estimates are shown as 95% highest posterior density intervals with 95% upper and 95% lower credible intervals.

Discussion

Climate change poses a significant threat to biodiversity across natural systems globally47. In coral reef ecosystems, recurrent mass bleaching episodes have led to dramatic loss of coral in response to heat stress25. Here, contrary to wholesale declines in coral populations across taxa, size classes and habitats recorded on the GBR20, we found more nuanced and optimistic results in a subtropical warming hotspot south of the GBR. Although endemic Pocillopora experienced marked declines in the decade surrounding the 2016 bleaching event, decadal stability of Turbinaria despite high incidence of bleaching, coupled with abundance increase and bleaching resistance observed in Acropora indicate remarkable resilience of these taxa in the subtropics. Shifts away from small corals point to bottlenecks to population replenishment for all taxa16,48 with abundance patterns of small corals best explained by thermal extremes (Pocillopora, Acropora) and patterns in chlorophyll a concentrations (Turbinaria). Nevertheless, persistence of larger corals despite higher incidence of bleaching and partial mortality, could boost recovery due to disproportionate contribution of large corals to population growth rates via survival, colony growth49 and reproduction18. Our findings support the notion that subtropical reefs are ecologically distinct from tropical coral reefs30,50,51, highlighting disparity in population dynamics11 and bleaching responses24,48 compared to tropical coral reefs.

Patterns in coral abundance

While we recorded declines in the abundance of small corals for all taxa and periods (declines of Turbinaria in Period 1 vs. 2 and Acropora in Period 2 vs. 3 based on 66% credible intervals), the number of medium and large corals followed a stable to upward trajectory for all taxa up until 2016, consistent with corals growing into larger size classes. In the aftermath of coral bleaching, the abundance of medium and large corals declined, apart from slight abundance increases of large Turbinaria corals (Fig. 4). This pattern likely reflects disproportionate bleaching and partial mortality of larger corals (Fig. 5). The decadal declines in the number of small corals reported here mirror long-term declines in the abundance of small corals on the GBR20 and are consistent with recruitment limitation and post-settlement mortality on high-latitude reefs28. Indeed, multiple lines of evidence point to recruitment bottlenecks on subtropical reefs in eastern Australia, ranging from settlement studies using tiles29 to size-based demographic studies16,27,48 and dispersal models that show limited connectivity with the southern GBR at spawning time23. Moreover, disturbance can cause high post-settlement mortality of early recruits14,15, especially when impacted by multiple disturbances such as coral bleaching and storms52, and in systems with high abundance of macroalgae53. Subtropical reefs are naturally exposed to marginal conditions8,21,50 that are further exacerbated by extreme storm events, and recently also by heat stress16,24. It is thus plausible that these factors, in combination with high abundance of macroalgae and sessile invertebrates31,50 limit coral establishment and impair recovery following disturbance.

Variable associations with environmental drivers

Variable links between the abundance of small corals and environmental drivers across taxa shows that in the subtropics, corals are exposed to complex multi-stressor regimes, particularly extremes in temperature and eutrophication. Indeed, negative association of the number of small Acropora corals with both degree cooling and heating weeks, illustrates their sensitivity to both cold and heat stress at high latitudes, where DCW1C reached 13.52 °C in 2012 and DHW0C reached 7.54 °C weeks in 2016. The number of small Pocillopora corals was positively associated with higher average temperatures, but still sensitive to accumulated heat stress (DHW0C). This vulnerability to heat stress is consistent with high incidence of bleaching of the subtropical endemic Pocillopora aliciae recorded here and by Lachs et al.16, and of Pocillopora species in the subtropical region more broadly24. Notably, the abundance of small Turbinaria corals was best explained by gradients in chlorophyll a, with small corals faring better in high-nutrient conditions (Fig. 6). These taxon-specific results highlight nuanced relationships with varying environmental conditions in this region, likely mediated by inhibitory effects of thermal extremes for Pocillopora and Acropora, and by stimulatory effects of food availability in higher chlorophyll a conditions for Turbinaria via heterotrophic feeding54,55.

While the role of thermal stress on coral biology and ecology is well established, other factors such as food availability are less often explored. Yet, heterotrophic feeding and trophic plasticity are important when it comes to regulating persistence in abiotically stressful conditions55,56. For example, heterotrophic feeding increases resilience to coral bleaching in turbid7 and chlorophyll a environments (e.g., in Yap, Micronesia, where eddies enhance productivity on the leeward side of islands)57, boosts reproductive output58, and influences calcification and growth rates55. The capacity to exploit these strategies relies on food availability, which tends to be higher in nutrient-rich settings such as turbid and high-latitude environments. Indeed, Fox et al.54 found that many corals increase heterotrophy as a function of food availability. In Bremer Bay, Western Australia (34.3° S) for instance, calcification rates for Turbinaria reniformis were elevated when chlorophyll a concentrations were higher during winter, despite cooler temperatures59. On mesophotic high-latitude reefs at Rottnest Island (32° S), Coscinaraea marshae corals that survived in a bleached state for more than 11 months showed signs of increased heterotrophic feeding60. The relative stability of Turbinaria abundance over our 10-year study, despite high incidence of coral bleaching, also supports the positive role of food availability on persistence of Turbinaria corals in subtropical environments. Nevertheless, phytoplankton blooms (typically measured as chlorophyll a concentrations) can also impose nutrient stress on corals and negatively affect their physiological performance, such as leading to reduced reproductive success, calcification, or linear extension61. These effects vary among species and might contribute to variation in demographic structure among taxa and between inshore and offshore sites (Figs. 3, 4, and 5), probably linked to variable encroachment of the EAC and subtle differences in environmental regimes32,34,35.

Taxonomic and size-based responses to disturbance

Subtropical reefs are sometimes heralded as thermal refugia for tropical species in warming seas, yet mounting evidence shows that they are also vulnerable to coral bleaching24,62,63,64,65 and future climate risks66. In this study, the subtropical endemic Pocillopora alicae had the highest incidence of coral bleaching, followed by Turbinaria and minimal bleaching of Acropora. This is consistent with other studies, showing that genera normally among the first to bleach in the tropics (e.g., Acropora) were less vulnerable to bleaching in marginal or extreme environments7. In the subtropics, endemic species, subtropical specialists24 and species close to their northern distributional limits65 typically have higher rates of bleaching, possibly because they live close to their upper thermal limits.

Body size influences the physiology, demography and ecology of organisms including how they respond to disturbance13,67. For example, mortality from extreme drought disproportionately affects larger trees13 and corals of certain growth forms (e.g., tabular corals) become increasingly susceptible to hydrodynamic dislodgement as they grow67. We have found size-dependent incidence of coral bleaching and partial mortality in the subtropics (Fig. 5). Specifically, larger Turbinaria and Pocillopora colonies had a higher probability of bleaching than smaller colonies. This is consistent with efficient mass transfer in small corals68 and positive size-bleaching relationships in experimental and field studies from subtropical Japan68, the Mediterranean69, French Polynesia14, and the Great Barrier Reef26, but in contrast with Pocillopora meandrina populations in Hawaii that showed the opposite pattern70. Differences in the shape of these relationships (Fig. 5) are likely due to disparity in the bleaching severity between Pocillopora and Turbinaria species, with severe and mild bleaching of these taxa, respectively24.

Furthermore, we found that larger Acropora and Pocillopora corals had greater odds of partial mortality than smaller ones, consistent with patterns found on disturbed reefs in the Caribbean42 and the general expectation that rates of partial mortality increase with colony size12. Unsurprisingly, bleached corals had a greater probability of partial mortality compared to unbleached corals, and the odds of suffering partial mortality were higher in the latter periods compared to Period 1 for all taxa (but not significant for Turbinaria). This points to elevated physiological stress following coral bleaching and is consistent with higher incidence of partial mortality after coral bleaching in the Galapagos Islands71.

Implications

The post-bleaching effects on coral populations may not become evident until years after the event72. For instance, mortality of adult size-classes can lead to collapse in recruitment in the years following bleaching18, and recovery can be suppressed for several years under chronic stress73. Moreover, sublethal stress can depress growth rates74 and fecundity18,75 of surviving corals, with negative effects on population growth and increases in mean colony size12,20. Indeed, this is likely to have occurred at the Solitary Islands Marine Park, as supported by declines in the number of small corals and increases in mean colony size for all taxa post bleaching. This suggests that coral recovery in the Solitary Islands was incomplete during the three-year period of data collection following bleaching, consistent with GBR recovery projections of at least seven years (to 70% of pre-disturbance levels) in the absence of disturbance73.

While some studies have reported the selective loss of larger corals and declines in mean colony size after disturbance (reviewed in12), we found the opposite pattern in the subtropics, consistent with long-term stability of large corals on high-latitude reefs in South Africa28. Indeed, the decadal stability of Turbinaria populations despite high incidence of coral bleaching (0.653 probability), and the abundance increase and bleaching resistance of Acropora corals recorded in this study point to remarkable resilience of these taxa in the subtropics. This supports the results of coral cover-based studies (i.e., not accounting for the size of individual corals) that predated the 2016 bleaching event and showed long-term stability of coral assemblages despite warming in this region23. Notwithstanding the loss of Pocillopora corals recorded here and the absence of heat stress, we predict that remnant Pocillopora will undergo recovery in the coming years, especially in light of their brooding reproduction and higher reproductive success in the region compared to other taxa29, properties that enhance their ability to increase population growth following disturbance (i.e., their capacity for demographic compensation)11.

Although our study reveals some signs of coral resilience in this warming hotspot, it also underlines the vulnerability of subtropical coral populations to changing environmental conditions. Population decline is inevitable without recruitment and, alarmingly, all three taxa suffered decadal declines in the number of small corals, likely due to recruitment and mortality bottlenecks of early life-stage corals. Recruitment limitation could thus hamper population replenishment following disturbance. While subtropical coral populations appear to be well adapted to the dynamic multi-stressor regime at high latitudes, taxon and size-specific bleaching and mortality indicate nuanced responses to heat stress and foreshadow vulnerability to changing disturbance regimes that include more frequent or severe heat stress events. Indeed, although population declines were greatest for Pocillopora corals in this study, projected long-term stochastic population growth trajectories suggest that the abundance of Pocillopora, Acropora and Turbinaria corals could drastically decline by 2100 under escalated future thermal stress in this region48. Nevertheless, the observed stability of large corals (Figs. 3 and 4) during the study period, despite higher incidence of bleaching and partial mortality, could bolster recovery because the largest corals in a population contribute disproportionately to reproduction76 and population growth49. Moreover, in these rocky reef environments where many coral species have massive and flat growth30, large branching Pocillopora, laminar Turbinaria and tabular Acropora corals provide structurally complex habitats for fish and invertebrates and could thus enhance associated biodiversity77. Larger corals are less likely to completely fit into our photographs than smaller corals and possibly bias our population size structure estimates towards smaller corals (see discussion in78). The observed decadal shift towards larger colonies and the positive scaling of disturbance responses with coral size are therefore likely conservative. Our study highlights the utility of long-term demographic studies to determine taxon and size-specific responses to changing disturbance regimes in marginal environments and implications for population recovery. It also emphasises the need for further studies into larval dispersal23 and the factors that influence settlement dynamics and success of early life-stage corals4,15,19,41,79 in this region to predict future population trajectories.

Data availability

Data used in this study and additional information are available upon request from the authors.

References

Capdevila, P., Stott, I., Beger, M. & Salguero-Gómez, R. Towards a comparative framework of demographic resilience. Trends Ecol. Evol. 35, 776–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.05.001 (2020).

Iida, Y. et al. Linking functional traits and demographic rates in a subtropical tree community: The importance of size dependency. J. Ecol. 102, 641–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12221 (2014).

De Bakker, D. M., Meesters, E. H., Bak, R. P. M., Nieuwland, G. & Van Duyl, F. C. Long-term shifts in coral communities on shallow to deep reef slopes of Curaçao and Bonaire: Are there any winners?. Front. Mar. Sci. 3, 247 (2016).

Doropoulos, C., Ward, S., Roff, G., Gonzalez-Rivero, M. & Mumby, P. J. Linking demographic processes of juvenile corals to benthic recovery trajectories in two common reef habitats. PLoS ONE 10, e0128535. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128535 (2015).

Sen Gupta, A. et al. Drivers and impacts of the most extreme marine heatwave events. Sci. Rep. 10, 19359. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75445-3 (2020).

Verges, A. et al. Long-term empirical evidence of ocean warming leading to tropicalization of fish communities, increased herbivory, and loss of kelp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 13791–13796. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1610725113 (2016).

Camp, E. F. et al. The future of coral reefs subject to rapid climate change: Lessons from natural extreme environments. Front. Mar. Sci. 5, 4 (2018).

Schoepf, V. et al. Corals at the edge of environmental limits: A new conceptual framework to re-define marginal and extreme coral communities. Sci. Total Environ. 884, 163688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163688 (2023).

Sommer, B., Butler, I. R. & Pandolfi, J. M. Trait-based approach reveals how marginal reefs respond to acute and chronic disturbance. Coral Reefs 40, 735–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-021-02077-y (2021).

Hilde, C. H. et al. The demographic buffering hypothesis: Evidence and challenges. Trends Ecol. Evol. 35, 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.02.004 (2020).

Cant, J. et al. Coral assemblages at higher latitudes favor short-term potential over long-term performance. Ecology 104, e4138. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.4138 (2023).

Pisapia, C. et al. In Advances in Marine Biology Vol. 87 (ed. Riegl, B. M.) 31–60 (Academic Press, 2020).

Stovall, A. E. L., Shugart, H. & Yang, X. Tree height explains mortality risk during an intense drought. Nat. Commun. 10, 4385. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12380-6 (2019).

Speare, K. E., Adam, T. C., Winslow, E. M., Lenihan, H. S. & Burkepile, D. E. Size-dependent mortality of corals during marine heatwave erodes recovery capacity of a coral reef. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1342–1358. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16000 (2022).

Edmunds, P. J. Vital rates of small reef corals are associated with variation in climate. Limnol. Oceanogr. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.11650 (2020).

Lachs, L. et al. Linking population size structure, heat stress and bleaching responses in a subtropical endemic coral. Coral Reefs 40, 777–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-021-02081-2 (2021).

Edmunds, P. J. & Riegl, B. Urgent need for coral demography in a world where corals are disappearing. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 635, 233–242. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13205 (2020).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming impairs stock–recruitment dynamics of corals. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1081-y (2019).

Sarribouette, L., Pedersen, N. E., Edwards, C. B. & Sandin, S. A. Post-settlement demographics of reef building corals suggest prolonged recruitment bottlenecks. Oecologia https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-022-05196-7 (2022).

Dietzel, A., Bode, M., Connolly, S. R. & Hughes, T. P. Long-term shifts in the colony size structure of coral populations along the Great Barrier Reef. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 287, 20201432. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.1432 (2020).

Sommer, B., Beger, M., Harrison, P. L., Babcock, R. C. & Pandolfi, J. M. Differential response to abiotic stress controls species distributions at biogeographic transition zones. Ecography 41, 478–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02986 (2018).

Wu, L. et al. Enhanced warming over the global subtropical western boundary currents. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1353 (2012).

Mizerek, T. L. et al. No evidence for tropicalization of coral assemblages in a subtropical climate change hot spot. Coral Reefs 40, 1451–1461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-021-02167-x (2021).

Kim, S. W. et al. Refugia under threat: Mass bleaching of coral assemblages in high-latitude eastern Australia. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 3918–3931. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14772 (2019).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543, 373–377. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21707 (2017).

Burn, D., Hoey, A. S., Matthews, S., Harrison, H. B. & Pratchett, M. S. Differential bleaching susceptibility among coral taxa and colony sizes, relative to bleaching severity across Australia’s Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea Marine Parks. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 191, 114907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.114907 (2023).

Precoda, K. et al. How does a widespread reef coral maintain a population in an isolated environment?. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 594, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12537 (2018).

Porter, S. N. & Schleyer, M. H. Long-term dynamics of a high-latitude coral reef community at Sodwana Bay, South Africa. Coral Reefs 36, 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-016-1531-z (2017).

Fairfull, S. J. L. & Harriott, V. J. Succession, space and coral recruitment in a subtropical fouling community. Mar. Freshw. Res. 50, 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF97267 (1999).

Sommer, B., Harrison, P. L., Beger, M. & Pandolfi, J. M. Trait-mediated environmental filtering drives assembly at biogeographic transition zones. Ecology 95, 1000–1009. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-1445.1 (2014).

Harriott, V. J., Smith, S. D. A. & Harrison, P. L. Patterns of coral community structure of subtropical reefs in the Solitary-Islands Marine Reserve, Eastern Australia. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 109, 67–76 (1994).

Malcolm, H. A., Davies, P. L., Jordan, A. & Smith, S. D. A. Variation in sea temperature and the East Australian Current in the Solitary Islands region between 2001–2008. Deep Sea Res. Part Ii Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 58, 616–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2010.09.030 (2011).

Lachs, L. et al. SizeExtractR: A workflow for rapid reproducible extraction of object size metrics from scaled images. Ecol. Evolut. 12, e8724. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8724 (2022).

Everett, J. D., Baird, M. E., Roughan, M., Suthers, I. M. & Doblin, M. A. Relative impact of seasonal and oceanographic drivers on surface chlorophyll a along a Western Boundary Current. Prog. Oceanogr. 120, 340–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2013.10.016 (2014).

Messer, L. F. et al. Microbial tropicalization driven by a strengthening western ocean boundary current. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 5613–5629. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15257 (2020).

Skirving, W. J. et al. (2018).

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, O. E. L., Ocean Biology Processing Group.

van Hooidonk, R. & Huber, M. Quantifying the quality of coral bleaching predictions. Coral Reefs 28, 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-009-0502-z (2009).

González-Espinosa, P. C. & Donner, S. D. Predicting cold-water bleaching in corals: Role of temperature, and potential integration of light exposure. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 642, 133–146. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13336 (2020).

Veron, J. E. N. & Minchin, P. R. Correlations between sea-surface temperature, circulation patterns and the distribution of hermatypic corals of Japan. Cont. Shelf Res. 12, 835–857 (1992).

Abrego, D. et al. Factors limiting the range extension of corals into high-latitude reef regions. Diversity https://doi.org/10.3390/d13120632 (2021).

Meesters, E. H. et al. Colony size-frequency distributions of scleractinian coral populations: Spatial and interspecific variation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 209, 43–54 (2001).

Caley, M. J. et al. Recruitment and the local dynamics of open marine populations. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 27, 477–500. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.477 (1996).

Hoey, A. S., Pratchett, M. S. & Cvitanovic, C. High macroalgal cover and low coral recruitment undermines the potential resilience of the world’s southernmost coral reef assemblages. PLoS ONE 6, e25824. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025824 (2011).

Chong-Seng, K. M., Graham, N. A. J. & Pratchett, M. S. Bottlenecks to coral recovery in the Seychelles. Coral Reefs 33, 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-014-1137-2 (2014).

Bürkner, P.-C. brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 80, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v080.i01 (2017).

Scheffers, B. R. et al. The broad footprint of climate change from genes to biomes to people. Science 354, aaf7671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf7671 (2016).

Cant, J. et al. The projected degradation of subtropical coral assemblages by recurrent thermal stress. J. Anim. Ecol. 90, 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13340 (2021).

Shlesinger, T. & van Woesik, R. Different population trajectories of two reef-building corals with similar life-history traits. J. Anim. Ecol. 90, 1379–1389. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13463 (2021).

Beger, M., Sommer, B., Harrison, P. L., Smith, S. D. A. & Pandolfi, J. M. Conserving potential coral reef refuges at high latitudes. Divers. Distrib. 20, 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12140 (2014).

Sommer, B. et al. Local and regional controls of phylogenetic structure at the high-latitude range limits of corals. Proc. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. Ser. B https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.0915 (2017).

Mumby, P. J. Bleaching and hurricane disturbances to populations of coral recruits in Belize. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 190, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.3354/MEPS190027 (1999).

Johns, K. A. et al. Macroalgal feedbacks and substrate properties maintain a coral reef regime shift. Ecosphere 9, e02349. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2349 (2018).

Fox, M. D. et al. Gradients in primary production predict trophic strategies of mixotrophic corals across spatial scales. Curr. Biol. 28, 3355-3363.e3354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.08.057 (2018).

Houlbrèque, F. & Ferrier-Pagès, C. Heterotrophy in tropical scleractinian corals. Biol. Rev. 84, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00058.x (2009).

Travaglione, N. et al. Scleractinian corals rely on heterotrophy in highly turbid environments. Coral Reefs https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-023-02407-2 (2023).

Keighan, R., van Woesik, R., Yalon, A., Nam, J. & Houk, P. Moderate chlorophyll-a environments reduce coral bleaching during thermal stress in Yap, Micronesia. Sci. Rep. 13, 9338. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36355-2 (2023).

Bellworthy, J., Spangenberg, J. E. & Fine, M. Feeding increases the number of offspring but decreases parental investment of Red Sea coral Stylophora pistillata. Ecol. Evolut. 9, 12245–12258. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.5712 (2019).

Ross, C. L., DeCarlo, T. M. & McCulloch, M. T. Environmental and physiochemical controls on coral calcification along a latitudinal temperature gradient in Western Australia. Glob. Change Biol. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14488 (2018).

Bessell-Browne, P., Stat, M., Thomson, D. & Clode, P. Coscinaraea marshae corals that have survived prolonged bleaching exhibit signs of increased heterotrophic feeding. Coral Reefs 33, 795–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-014-1156-z (2014).

D’Angelo, C. & Wiedenmann, J. Impacts of nutrient enrichment on coral reefs: New perspectives and implications for coastal management and reef survival. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain 7, 82–93 (2014).

Cook, C. B., Logan, A., Ward, J., Luckhurst, B. & Berg, C. J. Elevated temperatures and bleaching on a high latitude coral reef: The 1988 Bermuda event. Coral Reefs 9, 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00686721 (1990).

Moore, J. A. Y. et al. Unprecedented mass bleaching and loss of coral across 12° of latitude in Western Australia in 2010–11. PLoS ONE 7, e51807. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051807 (2012).

Moriarty, T., Leggat, W., Heron, S. F., Steinberg, R. & Ainsworth, T. D. Bleaching, mortality and lengthy recovery on the coral reefs of Lord Howe Island. The 2019 marine heatwave suggests an uncertain future for high-latitude ecosystems. PLoS Clim. 2, e0000080. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000080 (2023).

Thomson, D. P., Bearham, D., Graham, F. & Eagle, J. V. High latitude, deeper water coral bleaching at Rottnest Island, Western Australia. Coral Reefs 30, 1107–1107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-011-0811-x (2011).

Kim, S. W., Sommer, B., Beger, M. & Pandolfi, J. M. Regional and global climate risks for reef corals: Incorporating species-specific vulnerability and exposure to climate hazards. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 4140–4151. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16739 (2023).

Madin, J. S. & Connolly, S. R. Ecological consequences of major hydrodynamic disturbances on coral reefs. Nature 444, 477–480. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05328 (2006).

van Woesik, R., Irikawa, A., Anzai, R. & Nakamura, T. Effects of coral colony morphologies on mass transfer and susceptibility to thermal stress. Coral Reefs https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-012-0911-2 (2012).

Shenkar, N., Fine, M. & Loya, Y. Size matters: Bleaching dynamics of the coral Oculina patagonica. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 294, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps294181 (2005).

Johnston, E. C. et al. The legacy of stress: Coral bleaching impacts reproduction years later. Funct. Ecol. 34, 2315–2325. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13653 (2020).

Riegl, B. et al. Some environmental and biological determinants of coral richness, resilience and reef building in Galápagos (Ecuador). Sci. Rep. 9, 10322. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46607-9 (2019).

Baird, A. H. & Marshall, P. A. Mortality, growth and reproduction in scleractinian corals following bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 237, 133–141 (2002).

Ortiz, J.-C. et al. Impaired recovery of the Great Barrier Reef under cumulative stress. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar6127. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aar6127 (2018).

Pratchett, M. S. et al. Spatial, temporal and taxonomic variation in coral growth—Implications for the structure and function of coral reef ecosystems. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev. 53, 215–295. https://doi.org/10.1201/b18733 (2015).

Leinbach, S. E., Speare, K. E., Rossin, A. M., Holstein, D. M. & Strader, M. E. Energetic and reproductive costs of coral recovery in divergent bleaching responses. Sci. Rep. 11, 23546. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02807-w (2021).

Hall, V. R. & Hughes, T. P. Reproductive strategies of modular organisms: Comparative studies of reef-building corals. Ecology 77, 950–963. https://doi.org/10.2307/2265514 (1996).

O’Connell, M. J., Fowler, A. M., Allan, S. J., Beretta, G. A. & Booth, D. J. Subtropical coral expansion into SE Australia: A haven for both temperate and expatriating tropical reef fishes. Coral Reefs 42, 1257–1262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-023-02429-w (2023).

Chong, F. et al. High-latitude marginal reefs support fewer but bigger corals than their tropical counterparts. Ecography 2023, e06835. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.06835 (2023).

Cooney, C., Sommer, B., Marzinelli, E. M. & Figueira, W. F. The role of microbial biofilms in range shifts of marine habitat-forming organisms. Trends Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2023.07.015 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank K-Le Gomez-Cabrera, Sun Kim, Carrie Sims, Nicole Kyriacou, Steve Dalton, Bob Edgar, Katie Cook and Dive Quest for assistance with fieldwork. Funding supporting this research was provided by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE230100141) and a University of Sydney Fellowship to BS, by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (CE140100020) to JMP and others, the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions (CE110001014) and the Winifred Violet Scott Charitable Trust to MB, the Royal Geographical Society’s Ralph Brown Expedition Grant to MB and JC, the Natural Environment Research Council’s Sphere Doctoral Training Partnership to JC and the Natural Environment Research Council’s ONE Planet Doctoral Training Partnership (NE/S007512/1) and the European Commission’s Erasmus Traineeship to LL. This project has further received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant agreement TRIM-DLV-747102 to MB.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.S., M.B., J.M.P., J.H. and L.L. developed the research ideas. B.S., M.B., J.C., J.M.P. and L.L. conducted field work and J.H. and L.L. annotated the field images. B.S. analysed the data and led the writing of the manuscript with all authors contributing critically to the writing and giving final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sommer, B., Hodge, J.M., Lachs, L. et al. Decadal demographic shifts and size-dependent disturbance responses of corals in a subtropical warming hotspot. Sci Rep 14, 6327 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56890-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56890-w

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.