Abstract

An effective method for synthesizing acridinedione derivatives using a xanthan gum (XG), Thiacalix[4]arene (TC4A), and iron oxide nanoparticles (IONP) have been employed to construct a stable composition, which is named Thiacalix[4]arene-Xanthan Gum@ Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (TC4A-XG@IONP). The process used to fabricate this nanocatalyst includes the in-situ magnetization of XG, its amine modification by APTES to get NH2-XG@IONP hydrogel, the synthesis of TC4A, its functionalization with epichlorohydrine, and eventually its covalent attachment onto the NH2-XG@IONP hydrogel. The structure of the TC4A-XG@IONP was characterized by different analytical methods including Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, X-Ray diffraction analysis (XRD), Energy Dispersive X-Ray, Thermal Gravimetry analysis, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller, Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope and Vibration Sample Magnetomete. With magnetic saturation of 9.10 emu g−1 and ~ 73% char yields, the TC4As-XG@IONP catalytic system demonstrated superparamagnetic property and high thermal stability. The magnetic properties of the TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst system imparted by IONP enable it to be conveniently isolated from the reaction mixture by using an external magnet. In the XRD pattern of the TC4As-XG@IONP nanocatalyst, characteristic peaks were observed. This nanocatalyst is used as an eco-friendly, heterogeneous, and green magnetic catalyst in the synthesis of acridinedione derivatives through the one-pot pseudo-four component reaction of dimedone, various aromatic aldehydes, and ammonium acetate or aniline/substituted aniline. A combination of 10 mg of catalyst (TC4A-XG@IONP), 2 mmol of dimedone, and 1 mmol of aldehyde at 80 °C in a ethanol at 25 mL round bottom flask, the greatest output of acridinedione was 92% in 20 min.This can be attributed to using TC4A-XG@IONP catalyst with several merits as follows: high porosity (pore volume 0.038 cm3 g−1 and Pore size 9.309 nm), large surface area (17.306 m2 g−1), three dimensional structures, and many catalytic sites to active the reactants. Additionally, the presented catalyst could be reused at least four times (92–71%) with little activity loss, suggesting its excellent stability in this multicomponent reaction. Nanocatalysts based on natural biopolymers in combination with magnetic nanoparticles and macrocycles may open up new horizons for researchers in the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The N-containing heterocyclic structures have been considered essential members of organic materials. They are the main scaffold of a wide spectrum of medicine and biologically active products1,2,3. These compounds have been attracted great attention for several decades because of their extensive applications in numerous fields, including medicine, veterinary products, disinfectants, and antioxidants4,5,6,7. In past years, multicomponent reactions (MCRs) have attracted the curiosity of pharmaceutical scientists, particularly for the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds with significant variety, for instance, Hantzsch and acridinedione derivatives8,9. Among the many medicinal and biological properties of acridinediones, they possess a wide range of activities such as ionotropic activity promoting calcium entry into cells, anticancer activity, inhibition of enzymes and tumor cells, antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity10. Several pharmaceuticals can be synthesized from 1,4-dihydropyridines (1,4-DHPs), often used in synthetic reactions as intermediates11. Different methods produce acridine derivatives (ADs), which are usually hazardous, expensive, and take quite a while to synthesize. The manufacturing of the diverse variety of chemicals that are essential to our contemporary society depends greatly on heterogeneous catalysts12,13. In addition to their selectivity, thermal stability, high surface area, high activity, nontoxicity, and recyclability for repeated reaction cycles, heterogeneous catalysts have a range of advantages as well14. The acridinedione moiety plays an instrumental role in synthesizing of bioactive heterocyclic molecules. Through designing and developing MCRs synthesis using sustainable principles and techniques and biobased catalysts, high-quality synthesis can be achieved. Ethyl acetoacetate, hydrazine hydrate, aldehydes, and malononitrile have been used in the MCRs process to synthesize ADs. g-C3N4@L-arginine15, Fe3O4@Polyaniline-SO3H16, GO/CR-Fe3O417, ionic liquids18, The aforementioned process began with catalysts such as imidazole19 and tetranitrophenol. The fact that bio-based catalysis is environmentally benign and has excellent biocompatibility, and chemical diversity over conventional catalysis, as a result of its benefits, including high activity and selectivity. The development of natural polymer-based catalysts has received attention recently due to their remarkable advantages such as their eco friendliness, hydrophilicity, abundance, availability, and low cost. Previous research has shown, a polysaccharide including Arabic Gum20, sodium alginate21, cellulose22, dextrin23, and chitosan24; their modified forms were commnoly employed as main components of the different catalytic systems25,26,27. Additionally, a wide range of hydratererocylic compounds can be synthesized via catalysis using magneticnatural polymer composites, including magnetic guanidinylated chitosan (MGCS) nanobiocomposite28, HNTs/Chit catalyst29, Hyd AG-g-PAN/ZnFe2O430, and Fe3O4@xanthan nanocatalyst31.

Xanthan gum (XG) a prominent example of polysaccharide that has attracted much attention in various industries and fields, including cosmetics, tissue engineering, drug delivery, wound healing, and the food industry32. Despite its incredible advantages, XG has several limitations, such as low specific surface area, heat resistance, difficulty in processability, insolubility in common organic solvents, instability and relatively poor hydrodynamic volume33. The chemical functionalization of this natural polymer by magnetic nanomaterials, supramolecules, synthetic polymers and also network formation of the natural polymers can be effectively enhancing their structural and chemical properties making them a promising candidate for organic reaction34,35.

Thiacalix[4]arenes (TC4A) are three-dimensional basket-like compounds considered a new category of calixarenes, a third generation of supramolecules. These are tetramers of phenols linked by sulfur atoms and have been identified as a prominent ligand for the construction of coordination cages and molecular clusters36. Indeed, the inclusion of sulfur atoms instead of the methylene bridges makes thiacalix[4]arenes particularly intriguing compounds, with with remarkable structural features that differ from the chemistry of "traditional" calixarenes 37. The TC4As are fascinating compounds with changeable conformations and excellent coordination ability, cavity structure, host–guest properties, versatile derivatization and high heat resistance has several applications in supramolecular chemistry36,38. The combination of TC4A with other materials and compounds can be used to construct different composites as sensors, absorbers, and catalysts in organic reactions39,40. Several catalytic systems based on calixarene have been shown to have effective catalytic characteristics for various organic processes.

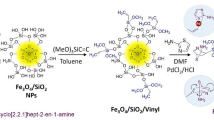

Hence, in continuing our efforts in designing and preparing the natural-polymer based heterogeneous catalyst, we aimed to construct a composed of the amine-modified XG, iron oxide nanoparticles, and TC4A, based on the covalent attachments using epichlorohydrin as organic linkers as illustrated in Fig. 1. The process used to fabricate the TC4A-XG@IONP Nanocatalyst including: (a) in-situ magnetization of XG, (b) its amine-modification by APTES, (c) the synthesis of TC4A, (d) its functionalization with ECH as a crosslinking agent, and eventually its covalent attachment onto the NH2-XG@IONP hydrogel matrix. The structure and physicochemical characteristics of the fabricated catalyst have been characterized by utilizing different analyses. The catalytic activity of the designed nanocatalyst have been assessed for the acridinedione derivatives. In this pseudo-fourcomponent condensation, a combination of ethyl acetoacetate, various aromatic aldehydes, ammonium acetate/aniline or substituted aniline, and NH4OAc were reacted to the synthesis acridinedione derivatives. It has been observed that all are synthesized with good to excellent yields by utilizing the designed TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst over a short reaction times.

Experimental

Materials and instruments

Xanthan gum (XG) (Sigma-Aldrich, Sigma-Aldrich Cas.no (G1253)), Ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O) (ACS reagent, 97%), (3-Aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES) (≥ 98%, Sigma-Aldrich),Tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether (≥ 99%, Sigma-Aldrich), Para-tert-butyl-phenol (99%, Sigma-Aldrich), Sodium hydroxide (reagent grade, ≥ 98%, pellets (anhydrous), Sigma-Aldrich), Sulfur (powder, 99.98% trace metals basis), Toluene (anhydrous, 99.8%, Sigma-Aldrich), Ethanol (96%, Sigma-Aldrich), Sulfuric acid (ACS reagent, 95.0–98.0%, Sigma-Aldrich), Diethyl ether (ACS reagent, anhydrous, ≥ 99.0%, contains BHT as an inhibitor, Sigma-Aldrich), Ammonia (puriss., anhydrous, ≥ 99.9%,Sigma-Aldrich), Epichlorohydrin (ECH) (purum, ≥ 99% (GC), Sigma-Aldrich).

FT-IR spectroscopy (Shimadzu FT-IR-8400S), EDX spectroscopy(Numerix DXP–X10P), VSM analysis (Meghnatis Kavir Kashan Co), BET analysis (BELCAT-A), XRD (DRON-8 X-ray diffractometer), EDX (VEGA-TESCAN-XMU), FESEM (Hitachi S-5200 and ZELSS SIGMA), TGA (BAHR-STA 504), Oven (Genlab Ltd), Zeta Meter (Zeta Meter Inc), H-NMR (VARIAN,INOVA 500 MHz).

Catalyst preparation

Preparation of IONP@XG

For preparing magnetic XG by co-precipitation method, 0.4 g XG was added to 85 ml d.w. in a double-mouthed flask. The temperature was raised to 45 °C until it was completely dissolved. FeCl2.4H2O (0.396 g, 2 mmol), FeCl3.6H2O (0.54 g, 4 mmol), and 10 ml d.w. were added to the mixture and stirred for 30 min to dissolve. Then, it was placed under a N2 atmosphere, and the temperature was raised and fixed at 80 °C. The mixture was stirred for 1 h after adding 8 ml of ammonia dropwise. After that, it was washed 10 times with d.w. and ethanol after that dried in an oven over 65 °C. Finally, a brown powder (IONP@XG) was obtained.

Preparation of IONP@XG-NH 2

0.5 g IONP@XG, 2 ml APTES, and 20 ml ethanol were poured into a round bottom flask and refluxed for 48 h. Then, it was washed seven times with ethanol, dried in an oven, and a brown powder (IONP@XG-NH2) was obtained.

Preparation of TC4A-XG@IONP

0.36 g prepared thiacalix[4]arene (TC4A was synthesized based on the reported procedure in literature41) and 35 ml ethanol were added to a 250 ml round bottom flask with a solution of NaOH (1 M) (to make the mixture basic) and stirred for 20 min. Next, 0.1 ml epichlorohydrin was added to the mixture, and litmus paper was used to check the basic of the mix. Then, the temperature was raised to 60 °C, and the mixture was stirred for 3 h. After that, 0.5 g IONP@XG-NH2 and 25 ml distilled water were added and stirred for 16 h. Then, the mixture was filtered, washed with distilled water and ethanol, and dried in an oven. Finally, a dark brown powder (TC4A-XG@IONP) was obtained. The preparation route of the TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst is illustrated in Fig. 2.

General procedure for the synthesis of acridinedione derivatives

A 25 ml round bottom flask was filled with a combination of aldehyde (1 mmol), dimedone (2 mmol), ammonium acetate/aniline/substituted aniline (1 mmol), TC4A-XG@IONP catalyst (0.01 g), and ethanol (5 ml), and the liquid was refluxed at 80 °C for 20 min. TLC kept track of the reaction's development. The combination was progressively cooled to room temperature when the reaction was finished. The nanocatalyst was then removed using external magnetic force, and the desired product was produced by recrystallizing with ethanol.

Selected spectral data

9-(4-chlorophenyl)-3,3,6,6-tetramethyl-10-(o-tolyl)-3,4,6,7,9,10-hexahydroacridine-1,8(2H,5H)-dione (6 g)

FT-IR (KBr, cm−1): 2952, 2870, 1635, 1579, 1489, 1222, 1087, 837, 737 cm−1. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ H (ppm) = 0.74(s, 6H, 2 CH3), 0.86(s, 6H, 2 CH3), 1.07(s, 3H, CH3), 1. 50(d, 2H, 2 CH), 2.21(m, 6H, 6 CH), 5.05(s, 1H, CH), 6.96–7.50(m, 8H, Ar–H) (Figs. S1 and S2).

3,3,6,6-Tetramethyl-9-(4-chlorophenyl)-3,4,6,7,9,10-hexahydroacridine1,8(2H,5H)-dione (5c)

FT-IR (KBr, cm−1): 2875, 2801, 1606, 1490, 1221, 1066, 887, 763 cm−1. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ H (ppm) = 0.68(s, 6H, 2 CH3), 0.85(s, 6H, 2 CH3), 1. 73(d, 2H, 2 CH), 1,98(d, 2H, 2 CH), 2.16(d, 2H, 2 CH), 2.21(d, 2H, 2 CH), 5.02(s, 1H, CH), 7.15–7.35(m, 4H, Ar–H), 7.42(b, 2H, Ar–H), 7.55–7.64(m, 3H, Ar–H) (Figs. S3 and S4).

Result and discussion

Characterization

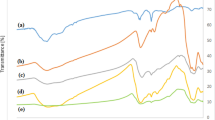

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy analysis

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis was applied to identify the functional groups of each step and the evidence for the final synthesis of TC4A-XG@IONP. The FT-IR spectra of (a) XG, (b) IONP@XG, (c) IONP@XG-NH2, (d) TC4A, and (e) TC4A-XG@IONP are shown in Fig. 3. The peaks about 1529, 1733, 2923, and 3386 cm-1 corresponded to stretching vibrations of CO–O, C=O, CH2, and OH of XG, shown in Fig. 3a42. In Fig. 3b, two peaks were added, about 575 and 1672 cm−1, related to C–O and Fe–O of IONP11. There is a characteristic peak of about 1654 cm−1 concerning the bending vibration of NH2 of IONP@XG-NH2 (Fig. 3c)43. In Fig. 3d, three characteristic peaks of TC4A were observed at 1205, 2945, and 3201 cm−1, which related to C–O, C–H, and O–H stretching vibrations, respectively44,45. Finally, in Fig. 3e, the stretch vibrations of C–O, C=C, C–H, and O–H are about 1026, 1654, 2924, and 3425 cm−1, which shows the complete synthesis of TC4A-XG@IONP.

Field emission scanning electron microscope analysis

The Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope imaging (FE-SEM) was used to observe the particle size distribution and surface morphology of nanocatalysts XG, IONP@XG, TC4A , TC4A-XG@IONP and shown in (Fig. 4a,b) The XG image illustrate a relatively uniform matrix and non-porous structure provide a relatively smooth and regular surface, in contrast the image of IONP@XG (Fig. 4c,d) spherical nanoparticles of iron oxide are completely visible in networks without aggregation in XG polymers46. Also, The TC4A images (Fig. 4e,f) have an average diameter of 50 nm found in the nanoparticle structure, which consists exclusively of rod-like structures. Graph of TC4A-XG@IONP (Fig. 4g,h) exhibited the presence of TC4A on the hydrogel network of TC4A-XG@IONP by chemical attachment.

Thermal gravimetry analysis

Thermal Gravimetry Analysis (TGA) evaluation of thermal resistance was performed on the samples XG, IONP@XG, IONP@XG-NH2, and TC4A-XG@IONP as shown in Fig. 5. TGA analysis of Fe3O4 was studied in detail to determine the thermal behavior of synthesized samples47. The reported thermal profile of iron oxide nanoparticles showed that its weight loss was about 5–6% up to 800 °C is related to the evaporation of surface absorbed water9. Figure 5a represent the thermal behavior of XG indicates that thermal degradation of this natural polymer begins at about 200 °C. The weight loss of 10% at 100 °C was due to the evaporation and outflow of water from the gum. This weight loss continued with increasing temperature, up to 300 °C, and after it went downhill48. About 50% of its weight is reduced between temperatures of 200–300 °C and its residuals weight at 800 °C is about 14%. The thermal profile of IONP@XG hydrogel (Illustrated in Fig. 5b) exhibited considerably elevated residual weight (73%) than unmodified XG over the studied range of temperature. This indicates the formation of iron oxide nanoparticles within the XG matrix and its effective interaction with chains of XG limits the mobility of chain of this natural polymer. Based on IONP@XG hydrogel thermogram, the first weight loss began at 270 °C which continued up to 400 °C and the second thermal decomposition observed between 400 and 800 °C. These are related to the surface dehydrogenation and dehydroxylation, dissociation of site chain and functional groups and decomposition of glycosidic bridge of XG. Thermal degradation of IONP@XG-NH2 as illustrated in Fig. 5c, showed similar trend with slightly decreased resudial weight (68%) as compared to IONP@XG48. The thermal degradation of the TC4A-XG@IONP showed three step decomposition (Fig. 5d). The initial weight loss in the temperature range of 50–200 °C caused by evaporation of adsorbed water in its cavities, the next one started at 250 °C and stained up to 300 °C which can be related to the breakdown the linkage between IONP@XG-NH2 and TC4A and thermal dissociation of XG functional groups. The last weight loss in the temperature range of 350–450 °C might be caused by thermal degradation of TC4A and depolymerization of XG. Modifying IONP@XG-NH2 with TC4A supermolecule increased its thermal resistance by 5%. Accordingly, TC4A-XG@IONP had relatively high thermal resistance with ~ 73% residual weight unto 800 °C.

Vibration sample magnetometer analysis

The vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM) analysis measured the synthesized nanocatalyst magnetic properties. According to (Fig. 6a), the property magnetic coercivity and the magnetic reluctance of TC4A-XG@IONP is zero. Therefore, the synthesized samples have superparamagnetic properties. The magnetic saturation value of IONP nanoparticles is 58 emu g−1, and saturation magnetization of IONP@XG and TC4A-XG@IONP are decreased to 30.060 emu g−1 and 9.300 emu g−1 as illustrated in Fig. 6b,c respectively. The decrease in magnetic saturation is related to XG and TC4A, a natural polysaccharide, and a macrocyclic compound, which none of them have a magnetic nature. However, the magnetic saturation of TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst is sufficient to separate it using a magnet in the experiments.

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller analysis

We conducted a nitrogen adsorption–desorption analysis by Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) to determine the specific surface area, porosity, and textural properties of the synthesized nanocatalyst. Based on BJH theory, Table 1 summarizes IONP@XG and TC4As-XG@Fe3O4 specific surface areas, pore volumes, and average pore diameters. Figure 7 illustrates type-IV isotherm profiles (with H4 hysteresis loops) for both nanocatalyst materials. Mesoporous materials are classified by IUPAC based on type-IV isotherm profiles. In contrast to neat XG, IONP@XG (Fig. 7a) showed a BET surface area of 45.317 m2 g−1, much higher than the 0.676 m2 g−1 previously reported for neat XG. For explanation of this observation can be said that, during the in-situ fabrication of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles in XG natural polymer matrix, the inherent coordination potential of Fe3+ (trivalent metal ion) in alkaline reaction media leads to the coordination bonding between hydroxylate and carboxylate functional groups of polymeric chains of XG natural and formation of three-dimention hydrogel network with improved surface area49. In the case of TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst (Fig. 7b), the BET surface area was measured 17.3065 m2 g−1, which was satisfactory compared to IONP@XG. The surface area and size of TC4A-XG@IONP were decreased following, amine-functionalization, and then covalent bonding to funtionalized TC4A. A nanocatalyst fabricated with favorable textural properties, a porous structure, and a high specific surface area may be considered as a desired catalytic system.

X-Ray diffraction analysis

The crystallinity of the produced materials in the range of 5–80° was investigated using X-Ray diffraction analysis (XRD) analysis50. According to earlier research, a distinctive peak (at 2θ = 18°–25°) was seen in the XRD pattern of XG, indicating that it is an amorphous material (Fig. 8b). As shown in Fig. 8a, the acceptable IONP pattern with card number JCPDS, 01-77-0010 fits the XRD pattern for LONP, which includes diffraction peaks at 2θ = 30.61° 35.99°, 43.27°, 54.18°, 57.53° and 63.35°. The same peaks as those associated with IONP have been identified for IONP@XG, but since XG is an amorphous material, their pitch is less intense (Fig. 8c). According to studies in the literature, TC4A has a crystalline structure in Fig. 8d. Additionally, the typical IONP peak can be seen in the XRD pattern of the TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst, confirming the existence of IONP MNPs there. Finally, it can be said that compared to pristine XG, in-situ magnetization,amine modification and functionalization with TC4As produced better crystallinity(Fig. 8e).

Energy dispersive X-ray

The detection and identification of organic and inorganic elements in the manufactured compounds was done by the Energy Dispersive X-Ray (EDX) qualitative analysis method51,52. Therefore, the constituent elements of the prepared samples can be examined in the EDX spectrum. As shown in Fig. 9a–e, the EDX spectrum of neat XG was illustrated in Fig. 9a with high intensity peaks represent to C, N, O, Na, Cl and Ca elements. On the analysis of the TC4A, the weight% (atomic%) values for C, O, and S are 74.59% (81.35%), 20.17% (16.52%), and 5.23% (2.14%) respectively,which are the main constituents of TC4A, are well visible in Fig. 9b. In the spectrum Fig. 9c the elements C, O and Fe are confirm the structure of IONP@XG. Spectrum Fig. 9d confirm the structure of IONP@XG-NH2 with the relayted elements (C, O, N, Si, and Fe). The peaks related to the final nanocatalyst (TC4A-XG@IONP), this diagrame also has high intensity peaks of the elements including C, O, N, S, and Fe are the main constituent elements that are shown with high intensity (Fig. 9e). A uniform distribution of elements is observed in (a) XG, (b) TC4A, (c) IONP@XG, (d) IONP@XG-NH2, and (e) TC4A-XG@IONP, as illustrated in Fig. S6 of the Supplementary Materials.

Catalytic study

The green and eco-friendly TC4A-XG@IONP was applied as a catalyst in organic reaction. For this purpose, it was used as a catalyst in synthesizing acridinedione derivatives. The one-pot reaction between dimedone, 4-chlorobenzaldehyde, ammonium acetate/aniline/substituted aniline, and ethanol as solvent was carried out as a model reaction. Different conditions like temperature, amount of catalyst, solvent, and reaction time were investigated and shown in Table 2. First, the reaction was performed without a catalyst at room temperature (rt) and 80 °C and observed there was no product, which shows the essential role of the catalyst (Table 2, Entry 1 and 2). Then, the reaction was applied at rt, 40 °C, and 80 °C, it was observed at 80 °C, the product yield was the highest (Table 2, Entry 3–5). Other green solvents including water, methanol, and acetonitrile were investigated, and ethanol as a solvent has the highest yield (Table 2, Entry 6–8). Also, the amount of catalyst was investigated, which observed that 20 mg catalyst is the optimized amount, and the extra amount does not affect yield (Table 2, Entry 9 and 10). The reaction time was also investigated at 10, 20, and 30 min. It was found that the optimized reaction time is 20 min, and more than, does not affect the yield of the intended product (Table 2, Entry 11–13). Moreover, the reaction performed by XG and TC4A. The results showed that the TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst has more yield, which shows the merits of its catalytic activity (Table 2, Entry 14 and 15).

After obtaining the optimized reaction conditions, various aldehyde and amine derivatives were used to show the TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalytic merits, and the intended products were obtained with high yields (Table 3).

In addition, the catalytic activity of TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst comparisons was made with some other catalysts reported (Table 4) and observed that using the synthesized nanocatalyst has a higher yield than the others. Based on this, it can be concluded that TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst is an efficient catalyst in synthesizing acridinedione derivatives.

Proposed mechanism

The green and multifunctional TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst can perfectly accelerate organic reactions due to the desired physicochemical properties as follows; large surface area, high porosity, three-dimentional network, and abundantly OH and NH2 groups. The plausible mechanism for synthesizing acridinedione derivatives with TC4A-XG@IONP as a nanocatalyst. First, the catalyst makes a hydrogen bonding with dimedone and makes the alpha hydrogen highly acidic. Then, aromatic aldehyde was activated by TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst, and dimedone made a nucleophilic attack and a knovenagel product was obtained. By dehydration, a Michael reaction would occur with another dimedone with acidic hydrogen through hydrogen bonding with TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst. Then ammonium acetate would react with the carbonyl group, and the intended product would be obtained with the help of a nanocatalyst by intramolecular cyclization and dehydration (Fig. S5).

Reusability

In green chemistry, the ability to reuse the catalyst is one of the main principles. So, the reusability of TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst was investigated in synthesizing the acridinedione derivatives. This process involved extracting the TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst from a mixture with an external magnet, washing it several times with ethanol and water, drying it in an oven, and reusing it for the reaction. As shown in Fig. 10a, the TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst was reused four times with no apparent diminish in the product yield. Also, the FT-IR of reused TC4A-XG@IONP is shown in Fig. 10b, and it is clear that the structure maintained its stability.

Conclusion

In the present work, we constructed a composition of XG and TC4A via covalent bonding in the presence of IONP and by using organosilane, and epichlorohydrine. The next step, the employed characterization methods have confirmed well the construction of TC4A-XG@IONP nanocatalyst. We then used that nanocatalyst to synthesize the acridinedione derivatives through one-pot multicomponent reaction of dimedone, various aromatic aldehydes, and different amines (ammonium acetate or aniline/substituted aniline). The corresponding products were synthesized with good to high yields (92–72%). The presented eco-friendly catalytic system has great textural and structural characteristics which originated from its constituent components, (i.e., XG, IONP, and TC4A) and their synergistic effects such as high porosity and presence of cavity shaped structure, high surface area, abundant reactive functional groups as catalytic sites, high thermal stability, and great retrievability, considering the great advantages that this nanocatalyst has for the acridinedione derivatives, still has challenges such as scalability challenge researchers could explore innovative approaches for producing the nanocatalyst on a larger scale while maintaining its catalytic activity and stability. This could involve investigating alternative synthesis methods or optimizing the current synthesis process to reduce production costs and increase yield. To evaluate the potential environmental impact of the nanocatalyst, researchers could conduct comprehensive toxicity studies to assess its effects on human health and the environment. They could also investigate methods for safely disposing of or recycling the nanocatalyst after use to minimize any negative environmental impacts.Overall, addressing these challenges will be crucial for advancing the development and application of the TC4A_XG@IONP nanocatalyst as a sustainable and efficient alternative for organic transformations in various industrial sectors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gao, B., Yang, B., Feng, X. & Li, C. Recent advances in the biosynthesis strategies of nitrogen heterocyclic natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1NP00017A (2022).

Haribabu, J., Garisetti, V. & Malekshah, R. E. Design and synthesis of heterocyclic azole based bioactive compounds: Molecular structures, quantum simulation, and mechanistic studies through docking as multi. J. Mol. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131782 (2022).

Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F. et al. Facile synthesis of pyrazolopyridine pharmaceuticals under mild conditions using an algin-functionalized silica-based magnetic nanocatalyst (Alg@SBA-15/Fe3O4). RSC Adv. 13, 10367–10378 (2023).

Teng, H. et al. The role of flavonoids in mitigating food originated heterocyclic aromatic amines that concerns human wellness. Food Sci. Human Wellness https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fshw.2022.10.019 (2023).

Hayat, K. et al. O-Halogen-substituted arene linked selenium-N-heterocyclic carbene compounds induce significant cytotoxicity: Crystal structures and molecular docking studies. J. Organomet. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jorganchem.2022.122593 (2023).

Abdussalam-Mohammed, W., Ali, A. Q. & Errayes, A. O. Green chemistry: Principles, applications, and disadvantages. Chem. Methodol. https://doi.org/10.33945/SAMI/CHEMM.2020.4.4 (2020).

Salehi, M. M., Esmailzadeh, F. & Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F. Applications of MOFs. Eng. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18675-2_13/COVER (2023).

Wu, H. et al. Magnetic negative permittivity with dielectric resonance in random Fe3O4@graphene-phenolic resin composites. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 1, 168–176 (2018).

Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F., Dogari, H., Esmailzadeh, F. & Maleki, A. Magnetized melamine-modified polyacrylonitrile (PAN@melamine/Fe3O4) organometallic nanomaterial: Preparation, characterization, and application as a multifunctional catalyst in the synthesis of bioactive dihydropyrano [2,3-c]pyrazole and 2-amino-3-cyano 4H-pyran derivatives. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 35, e6363 (2021).

Pei, Y., Wang, L., Tang, K. & Kaplan, D. L. Biopolymer nanoscale assemblies as building blocks for new materials: A review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2008552 (2021).

Maleki, A., Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F., Varzi, Z. & Esmaeili, M. S. Magnetic dextrin nanobiomaterial: an organic-inorganic hybrid catalyst for the synthesis of biologically active polyhydroquinoline derivatives by asymmetric. Mater. Sci. Eng. C https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2019.110502 (2020).

Peramune, D. et al. Recent advances in biopolymer-based advanced oxidation processes for dye removal applications: A review. Environ. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.114242 (2022).

Simionescu, B. C. & Ivanov, D. Natural and synthetic polymers for designing composite materials. In Handbook of Bioceramics and Biocomposites 233–286 (2016) doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12460-5_11.

Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R. et al. Recent advances in the application of mesoporous silica-based nanomaterials for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2019.110267 (2020).

Ghafuri, H., Bijari, F., Talebi, M., Tajik, Z. & Hanifehnejad, P. Graphitic carbon nitride-supported L-arginine: Synthesis, charachterization, and catalytic activity in multi-component reactions. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-26-13708 (2022)

Ghafuri, H., Moradi, S., Ghanbari, N., Dogari, H. & Ghafori, M. Efficient and green synthesis of acridinedione derivatives using highly Fe3O4@Polyaniline-SO3H as efficient heterogeneous catalyst. Proceed Chem https://doi.org/10.3390/ecsoc-25-11719 (2021).

Eyvazzadeh-Keihan, R., Bahrami, N., Taheri-Ledari, R. & Maleki, A. Highly facilitated synthesis of phenyl (tetramethyl) acridinedione pharmaceuticals by a magnetized nanoscale catalytic system, constructed of GO, Fe3O4 and creatine. Diam. Related Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2019.107661 (2020).

Kumar, P. S. V., Suresh, L., Bhargavi, G., Basavoju, S. & Chandramouli, G. V. P. Ionic liquid-promoted green protocol for the synthesis of novel naphthalimide-based acridine-1,8-dione derivatives via a multicomponent approach. ACS Sustain Chem. Eng. 3, 2944–2950 (2015).

Iqbal, N. et al. Acridinedione as selective flouride ion chemosensor: A detailed spectroscopic and quantum mechanical investigation. RSC Adv. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7RA11974G (2018).

Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F., Salehi, M. M., Heidari, G., Maleki, A. & Zare, E. N. Hydrolyzed Arabic gum-grafted-polyacrylonitrile@ zinc ferrite nanocomposite as an efficient biocatalyst for the synthesis of pyranopyrazoles derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.134490 (2023).

Elinson, M. N. et al. Utilization of monosodium glutamate (MSG) for the synthesis of 1, 8-dioxoacridine and polyhydro-quinoline derivates with SiO2-AA-glutamate catalyst and antioxidant. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/902/1/012071.

Sahiba, N., Sethiya, A., Soni, J. & Agarwal, S. Acridine-1,8-diones: Synthesis and biological applications. ChemistrySelect 6, 2210–2251 (2021).

Kheilkordi, Z., Ziarani, G., Badiei, A. & Sillanpää, M. Recent advances in the application of magnetic bio-polymers as catalysts in multicomponent reactions. RSC Adv. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2RA01294D (2022).

Sahiba, N. et al. A facile biodegradable chitosan-SO3H catalyzed acridine-1, 8-dione synthesis with molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation and density functional theory. J. Mol. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.133676 (2022).

Temel, F., Turkyilmaz, M. & Kucukcongar, S. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions by silica gel supported calix arene cage: Investigation of adsorption properties. Eur. Polym. J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2020.109540 (2020).

Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R. et al. Synthesis of core-shell magnetic supramolecular nanocatalysts based on amino-functionalized Calix[4]arenes for the synthesis of 4H-chromenes by ultrasonic waves. ChemistryOpen 9, 735–742 (2020).

Nasiriani, T. et al. Isocyanide-based multicomponent reactions in water: Advanced green tools for the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds. Top. Curr. Chem. 380, 50 (2022).

Maleki, A., Firouzi-Haji, R. & Hajizadeh, Z. Magnetic guanidinylated chitosan nanobiocomposite: A green catalyst for the synthesis of 1,4-dihydropyridines. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 116, 320–326 (2018).

Jelodar, D. F., Hajizadeh, Z. & Maleki, A. Halloysite nanotubes modified by chitosan as an efficient and eco-friendly heterogeneous nanocatalyst for the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds. Multidiscip. Dig. Publ. Inst. Proceed. 41, 59 (2019).

Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F., Salehi, M. M., Heidari, G., Maleki, A. & Zare, E. N. Hydrolyzed Arabic gum-grafted-polyacrylonitrile@ zinc ferrite nanocomposite as an efficient biocatalyst for the synthesis of pyranopyrazoles derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 1274, 134490 (2023).

Esmaeili, M. S., Khodabakhshi, M. R., Maleki, A. & Varzi, Z. Green, natural and low cost xanthum gum supported Fe3O4 as a robust biopolymer nanocatalyst for the one-pot synthesis of 2-amino-3-cyano-4H-pyran derivatives. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 41, 1953–1971. https://doi.org/10.1080/10406638.2019.1708418 (2020).

Riaz, T., Iqbal, M. W., Jiang, B. & Chen, J. A review of the enzymatic, physical, and chemical modification techniques of xanthan gum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 186, 472–489 (2021).

Sikora, M., Kowalski, S. & Tomasik, P. Binary hydrocolloids from starches and xanthan gum. Food Hydrocolloids. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2007.05.007 (2008).

Maleki, A., Rahimi, J., Hajizadeh, Z. & Niksefat, M. Synthesis and characterization of an acidic nanostructure based on magnetic polyvinyl alcohol as an efficient heterogeneous nanocatalyst for the synthesis of α. J. Organomet. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.12.002 (2019).

Dabiri, M., Salehi, P., Koohshari, M., Hajizadeh, Z. & Magee, D. I. An efficient synthesis of tetrahydropyrazolopyridine derivatives by a one-pot tandem multi-component reaction in a green media. Arkivoc https://doi.org/10.3998/ark.5550190.0015.40 (2014).

Hang, X. & Bi, Y. Thiacalix[4]arene-supported molecular clusters for catalytic applications. Dalton Trans. 50, 3749–3758 (2021).

Böhmer, V. Calixarenes, macrocycles with (almost) unlimited possibilities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 34, 713–745 (1995).

Yilmaz, M. & Sayin, S. Calixarenes in organo and biomimetic catalysis. Calixarenes Beyond 7, 19–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31867-7_27/COVER (2016).

Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F., Ranjbar, G., Salehi, M. M., Esmailzadeh, F. & Maleki, A. Thiacalix arene-functionalized magnetic xanthan gum (TC4As-XG@ Fe3O4) as a hydrogel adsorbent for removal of dye and pesticide from water medium. Sep. Purif. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2022.122700 (2023).

Creaven, B., Donlon, D. & McGinley, J. Coordination chemistry of calix arene derivatives with lower rim functionalisation and their applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2008.06.008 (2009).

Lakouraj, M. M., Hasanzadeh, F. & Zare, E. N. Nanogel and super-paramagnetic nanocomposite of thiacalix[4]arene functionalized chitosan: Synthesis, characterization and heavy metal sorption. Iran. Polym. J. (Engl. Ed.) 23, 933–945 (2014).

Inphonlek, S., Niamsiri, N., Sunintaboon, P. & Sirisinha, C. Chitosan/xanthan gum porous scaffolds incorporated with in-situ-formed poly (lactic acid) particles: Their fabrication and ability to adsorb anionic compounds. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125263 (2020).

Qiu, H. et al. Removal of Cu2+ from wastewater by modified xanthan gum (XG) with ethylenediamine (EDA). RSC Adv. 6, 83226–83233 (2016).

Norouzian, R. S. & Lakouraj, M. M. Preparation and heavy metal ion adsorption behavior of novel supermagnetic nanocomposite of hydrophilic thiacalix[4]arene self-doped polyaniline: Conductivity, isotherm, and kinetic study. Adv. Polym. Technol. 36, 107–119 (2017).

Iki, N. et al. Synthesis of p-tert-butylthiacalix arene and its inclusion property. Tetrahedron https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4020(00)00030-2 (2000).

Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F., Ranjbar, G., Salehi, M. M., Esmailzadeh, F. & Maleki, A. Thiacalix[4]arene-functionalized magnetic xanthan gum (TC4As-XG@Fe3O4) as a hydrogel adsorbent for removal of dye and pesticide from water medium. Sep. Purif .Technol. 306, 122700 (2023).

Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F. et al. Efficient removal of Pb (II)/Cu (II) from aqueous samples by a guanidine-functionalized SBA-15/Fe3O4. Sep. Purif. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120956 (2022).

Koyuncu, I. et al. Modification of PVDF membranes by incorporation Fe3O4@Xanthan gum to improve anti-fouling, anti-bacterial, and separation performance. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10, 107784 (2022).

Ribeiro, M. et al. Xanthan-Fe3O4 nanoparticle composite hydrogels for non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging and magnetically assisted drug delivery. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 4, 7712–7729 (2021).

Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F. et al. Carrageenan-grafted-poly(acrylamide) magnetic nanocomposite modified with graphene oxide for ciprofloxacin removal from polluted water. Alex. Eng. J. 82, 503–517 (2023).

Salehi, M. M., Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F., Heidari, G., Maleki, A. & Nazarzadeh Zare, E. In situ preparation of MOF-199 into the carrageenan-grafted-polyacrylamide@Fe3O4 matrix for enhanced adsorption of levofloxacin and cefixime antibiotics from water. Environ. Res. 233, 116466 (2023).

Dogari, H., Salehi, M. M., Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F., Saeidirad, M. & Maleki, A. Magnetic polyacrylonitrile-melamine nanoadsorbent (PAN-Mel@Fe3O4) for effective adsorption of Cd (II) and Pb (II) from aquatic area. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 298, 116871 (2023).

Taheri-Ledari, R. et al. Facile route to synthesize Fe3O4 @acacia–SO3H nanocomposite as a heterogeneous magnetic system for catalytic applications. RSC Adv. 10, 40055–40067 (2020).

Mahesh, P. et al. Magnetically separable recyclable nano-ferrite catalyst for the synthesis of acridinediones and their derivatives under solvent-free conditions. Chem. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1246/cl.15050344,1386-1388 (2015).

Zolfigol, M. A., Karimi, F., Yarie, M. & Torabi, M. Catalytic application of sulfonic acid-functionalized titana-coated magnetic nanoparticles for the preparation of 1,8-dioxodecahydroacridines and 2,4,6-triarylpyridines via anomeric-based oxidation. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 32, e4063 (2018).

Kiani, M. & Mohammadipour, M. Fe3O4@ SiO2–MoO3H nanoparticles: A magnetically recyclable nanocatalyst system for the synthesis of 1, 8-dioxo-decahydroacridine derivatives. RSC Adv. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA25571J (2017).

Taheri-Ledari, R., Rahimi, J. & Maleki, A. Synergistic catalytic effect between ultrasound waves and pyrimidine-2, 4-diamine-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles: applied for synthesis of 1, 4. Ultrason. Sonochem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104737 (2019).

Aher, D. S., Khillare, K. R. & Shankarwar, S. G. Incorporation of Keggin-based H3PW7Mo5O40 into bentonite: Synthesis, characterization and catalytic applications. RSC Adv. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RA01179K (2021).

Chavan, P. N., Pansare, D. N. & Shelke, R. N. Eco-friendly, ultrasound-assisted, and facile synthesis of one-pot multicomponent reaction of acridine-1,8(2H,5H)-diones in an aqueous solvent. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 66, 822–828 (2019).

Tiwari, K. N., Uttam, M. R., Kumari, P., Vatsa, P. & Prabhakaran, S. M. Efficient synthesis of acridinediones in aqueous media. Syn. Commun. 47, 1013–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/00397911.2017.1304556t (2017).

Shi, D. Q., Shi, J. W. & Yao, H. Three-component one-pot synthesis of polyhydroacrodine derivatives in aqueous media. Synth. Commun. 39, 664–675 (2009).

Kour, J., Gupta, M., Chowhan, B. & Gupta, V. K. Carbon-based nanocatalyst: An efficient and recyclable heterogeneous catalyst for one-pot synthesis of gem-bisamides, hexahydroacridine-1,8-diones and 1,8-dioxo-octahydroxanthenes. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 16, 2587–2612 (2019).

Baghbanian, S. M., Khanzad, G., Vahdat, S. M. & Tashakkorian, H. P-Sulfonic acid calix[4]arene as an efficient and reusable catalyst for the synthesis of acridinediones and xanthenes. Res. Chem. Intermed. 41, 9951–9966 (2015).

Dorehgiraee, A., Tavakolinejad Kermani, E. & Khabazzadeh, H. One-pot synthesis of novel 1, 8-dioxo-decahydroacridines containing phenol and benzamide moiety and their synthetic uses. J. Chem. Sci. 126, 1039–1047 (2014).

Bhagat, D. S. et al. A rapid and convenient synthesis of acridine derivatives using camphor sulfonic acid catalyst. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 51, 96–101 (2019).

Sarkar, P. & Mukhopadhyay, C. The synthesis of new 8-imino-1-one acridine derivatives catalyzed by a calix arene mono-acid core. Green Chem. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6GC02144A (2016).

Rezaei, R., Khalifeh, R., Rajabzadeh, M., Dorosty, L. & Doroodmand, M. M. Melamine-formaldehyde resin supported H+-catalyzed three-component synthesis of 1,8-dioxo-decahydroacridine derivatives in water and under solvent-free conditions. Heterocycl. Comm. 19, 57–63 (2013).

Mahesh, P., Kumar, B. D., Devi, B. R. & Murthy, Y. L. N. Synthesis of thioacridine derivatives using Lawesson’s reagent. Orient. J. Chem. 31, 1683–1686 (2015).

Nikpassand, M., Mamaghani, M. & Tabatabaeian, K. An efficient one-pot three-component synthesis of fused 1,4-dihydropyridines using HY-zeolit. Molecules 14, 1468–1474 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The Iran University of Science and Technology (IUST) Research Council provided some of the authors' support, which they gratefully acknowledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.H.-A. Data curation-Equal, Investigation, Writing—original draft-Equal, Review & editing-Equal. M.M.S. Data curation-Equal, Formal Analysis-Equal, Writing – original draft-Equal. G.R. Methodology-Equal, Formal Analysis-Equal. F.E. Formal analysis-Equal, Investigation-Equal. P.H., M.A., F.E.Y. Methodology-Equal, Writing—original draft-Equal. A.M. Conceptualization-Equal, Funding Acquisition-Equal, Supervision-Equal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassanzadeh-Afruzi, F., Salehi, M.M., Ranjbar, G. et al. Utilizing magnetic xanthan gum nanocatalyst for the synthesis of acridindion derivatives via functionalized macrocycle Thiacalix[4]arene. Sci Rep 13, 22162 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49632-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49632-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.