Abstract

The sense of self is a foundational element of neurotypical human consciousness. We normally experience the world as embodied agents, with the unified sensation of our selfhood being nested in our body. Critically, the sense of self can be altered in psychiatric conditions such as psychosis and altered states of consciousness induced by psychedelic compounds. The similarity of phenomenological effects across psychosis and psychedelic experiences has given rise to the “psychotomimetic” theory suggesting that psychedelics simulate psychosis-like states. Moreover, psychedelic-induced changes in the sense of self have been related to reported improvements in mental health. Here we investigated the bodily self in psychedelic, psychiatric, and control populations. Using the Moving Rubber Hand Illusion, we tested (N = 75) patients with psychosis, participants with a history of substantial psychedelic experiences, and control participants to see how psychedelic and psychiatric experience impacts the bodily self. Results revealed that psychosis patients had reduced Body Ownership and Sense of Agency during volitional action. The psychedelic group reported subjective long-lasting changes to the sense of self, but no differences between control and psychedelic participants were found. Our results suggest that while psychedelics induce both acute and enduring subjective changes in the sense of self, these are not manifested at the level of the bodily self. Furthermore, our data show that bodily self-processing, related to volitional action, is disrupted in psychosis patients. We discuss these findings in relation to anomalous self-processing across psychedelic and psychotic experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The self is a central organizing principle of our cognition and experience. The sense of self is composed of different levels or models1,2,3,4,5,6 subserved by different neural systems7,8,9,10,11,12,13, which in neurotypical states are manifested as a robust and unified phenomenological experience. Altered states of consciousness, such as those found in neurological, psychiatric, and psychedelic states, are known to alter this experience e.g.,14,15,16. Notably, psychosis and psychedelic states both produce hallucinations and substantial alterations in the sense of self e.g.,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, causing some researchers to consider the psychedelic experiences as psychotomimetic24,25. For example, psychedelic experiences may induce changes across many levels of self, from the narrative self26,27 to robust changes in the ‘minimal self’28. Changes in minimal self may include abnormal feelings of ownership over one’s body, aberrant bodily sensations, loss of spatial self-location, and even a loss of the sense of self—“ego dissolution”15,18,29,30. Indeed, “ego dissolution” is an extreme condition associated with high doses of psychedelics leading to a loss of segregation between oneself and one's surroundings and typically accompanied by a feeling of unity with the universe15,31.

Similarly, the disrupted self is a prominent feature in psychosis32,33,34,35,36,37,38. Schizophrenia patients show deficits across different levels of self, including narrative39,40, social41, and bodily23,34,42,43 models of the self. Positive symptoms in schizophrenia include diminished control over one’s thoughts and actions, which lead to “passivity” experiences like auditory hallucinations and thought insertion23,43,44. It has been proposed that abnormal predictive sensorimotor processes blur the demarcation of self-generated sensations and drive self-deficits in psychosis34,45,46. This, in turn, may cause one’s inner voice, thoughts, and actions to be felt as if they are generated by some external agent leading to symptoms found in psychosis22,43,47,48. Thus, both psychedelic and psychotic states are unique examples in which the fundamental dimensions of the bodily self are altered.

The bodily self consists of two fundamental aspects, Body Ownership, the experience of identifying with the body e.g.,49,50,51, and the Sense of Agency, the experience of control over one’s actions e.g.,5,43,52,53,54,55,56,57. Body Ownership relies on multisensory integration in which exteroceptive and interoceptive sensory signals are bound to form a coherent model of the self e.g.,5,12,58,59,60. For example, when the brain receives converging visual, tactile, and proprioceptive signals congruent with prior implicit models of the self, a feeling of ownership arises for this limb. The Sense of Agency is grounded in predictive motor and inference processes linking volitional actions to the predicted sensory outcomes e.g.,57,61,62. Previous work has shown that voluntary actions are accompanied by an efference copy, which is used to compute forward models predicting the expected sensory consequences e.g.,63,64,65. The comparison of the predicted and actual sensory feedback enables the agent to distinguish between internally and externally generated sensations. If they match, a feeling of a self-generated movement arises (that the action is self-generated), and this is accompanied by both behavioral66,67,68 and neural69,70,71,72 suppression of the sensory consequences. However, there are documented instances where actions have led to sharpened sensory information73,74,75. If there is a large discrepancy between an action's predicted and actual sensory outcomes, the action is not attributed to oneself. For example, if the visual outcome of an action is modified temporally e.g.,76,77,78, anatomically e.g.,56, or spatially e.g., 79,80,81, participants do not experience authorship of the action. Thus, both Body Ownership and Sense of Agency rely on integration of sensory signals, however, Sense of Agency utilizes information from volitional action which can be used to improve inferences on the bodily self82.

The experimental study of the bodily self has relied heavily on the induction of illusory states of Body Ownership and Sense of Agency. In their seminal work, Botvinick and Cohen revealed that Visuotactile stimulation on a visible rubber hand, synchronous to tactile stimulation on one’s unseen real hand, induces illusory ownership over the rubber hand83. The rubber hand illusion, as well as full body and virtual versions of this paradigm, have become a mainstay of experimental research on the bodily self e.g.,1,13,84,85,86. Indeed, numerous subsequent studies have shown that induction of illusory Body Ownership is accompanied by replicable behavioral, physiological, and neural states87,88,89,90. Sense of Agency is typically tested by introducing discrepancies between participants’ movements and their visual consequences. For example, several studies have used temporal or spatial visuomotor discrepancies to alter and decrease the experience of Sense of Agency e.g.,56,76,86,91. Most experiments have focused on either Body Ownership or Sense of Agency such that their interactions were neglected. The Moving Rubber Hand illusion, a paradigm introduced a decade ago by Kalckert and Ehrsson allowed examining both Body Ownership and Sense of Agency by introducing both Visuotactile and Visuomotor illusions in a within-subject design92,93.

Here we used the Moving Rubber Hand illusion to examine alterations in the bodily self across participants with substantial psychedelic experience, participants with psychosis, and neurotypical controls. In psychosis, there is substantial evidence of impairments in Sense of Agency22,34,94. Across different paradigms, participants on the psychosis spectrum show a reduced ability to discriminate self-initiated actions95. Recent evidence has shown that this deficit is even present in non-symptomatic 22Q11DS participants with a genetic propensity for psychosis, suggesting Sense of Agency deficits may be a precursor of the psychotic state38. This aberrant Sense of Agency has been suggested to stem from abnormal predictive sensorimotor processes, which have been causally shown to induce psychosis-like states14,96. While there is converging evidence for Sense of Agency deficits in psychosis, the state of Body Ownership is less clear. While early reports reported abnormal processing of the Rubber Hand illusion in schizophrenia, recent empirical and meta-analytical work has shown no differences between control and schizophrenia participants for Body Ownership97. Classic psychedelics, which have been suggested to mimic psychosis symptoms98,99, also induce striking alterations of self, including strange sensations of the bodily self e.g.,30,100. These have been suggested to drive by changes in neural connectivity primarily due to the activation of 5HT2A receptors24,101,102,103. However, while subjective reports of acute and long-term changes in the sense of self after psychedelic use exist104,105, experimental evidence is conspicuously lacking. In this experiment, we compared Body Ownership and Sense of Agency using the Moving Rubber Hand illusion in participants with psychosis, participants with a history of substantial psychedelic experiences, and neurotypical controls.

Materials and methods

Participants

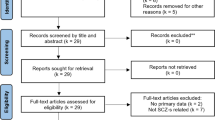

Seventy-five, right-handed participants took part in the experiment (27 females; Age M = 29.9, SD = 8.85). There were three groups of participants: Control (N = 25; 16 females; Age M = 24.84, SD = 6.28), Psychedelic (N = 25; 11 females; Age M = 28.8, SD = 6.01), and Psychosis (N = 25; all males; Age M = 36.08, SD = 10.39). The sample size was determined by previous studies using the Rubber Hand Illusion or the Moving Rubber Hand Illusion with similar sample sizes106,107,108,109,110. The Control and Psychedelic groups included participants who self-reported no history of neurological, psychiatric, or tactile and motor disorders and any use of associated medications. Participants in the Psychedelic group were collected by approaching psychedelic social media groups and all participants reported psychedelic substance use, whereas in the Control group, they reported no use (see Supplementary Fig. S2). In the psychedelic cohort 50% reported having experienced psychedelics over 15 times and about 25% reporting having used psychedelics over 50 times. The Psychosis group included patients with psychosis hospitalized at the Beer Yaakov-Ness Ziona Mental Health Center (see Supplementary Table S4). The experiment was performed following the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Gonda Multidisciplinary Brain Research Center ethics committee (for the Control and Psychedelic groups) and by the Beer Yaakov-Ness Ziona Mental Health Center ethics committee (for the Psychosis group). All participants gave written informed consent before the experiment. The Psychosis group had a higher mean age than other groups, Wilcoxon rank-sum test (Psychosis vs. Control: W = 505.5, p < 0.001; Psychosis vs. Psychedelic: W = 447.5, p < 0.01).

Assessment of psychedelic use and changes in Self

The Psychedelic and Control groups self-reported their frequency of use of psychedelic substances as well as other substances (e.g., alcohol and other compounds see Supplementary Fig. S2–S6). We wished to assess changes in the Sense of Self and especially the bodily self, due to psychedelic experiences. We thus chose to rely on previously established questionnaires, while focusing on items particularly relevant to the study’s main aim. Specifically, to assess changes in the sense of self following psychedelic use, we constructed a questionnaire examining altered self-experiences using 18 statements gathered from several well-established questionnaires (Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI)31, Cambridge Depersonalization Scale (CDS)111, and the Pahnke-Richards Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ)112 that examine the frequency and duration of experiences such as depersonalization, ego-dissolution, internal and external unity, and transcendence of time and space. These included items such as “Whilst doing something I have the feeling of being a detached observer of myself” and “I cannot feel properly the objects that I touch with my hands for it feels as if it were not me who was touching it” measuring depersonalization. Other items such as “I experienced a disintegration of my self or ego” and “All notion of self and identity dissolved away” probed other aspects such as ego-dissolution (see Supplementary Table S2 for full questionnaire details). The questionnaire was completed by both the Psychedelic and Control groups. To assess whether psychedelic use is associated with increased altered self-experiences, we compared the questionnaire scores for each section (EDI, CDS, and MEQ) between the Psychedelic and Control groups using a Mann–Whitney test. Psychosis patients’ clinical symptoms were assessed by a clinician via the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (see the clinical characteristics of Psychosis patients in Supplemental Table S4).

Experimental setup

We used an adaptation of the Moving Rubber Hand illusion setup to assess both Body Ownership and Sense of Agency92,93. Participants sat at a table with their right hand hidden from their view and placed inside a box (35 cm × 25 cm × 12 cm). A realistic life-size and gender-matched rubber hand model was placed on top of the box and covered with a latex glove identical to the participants’ glove. The participant’s forearm was covered with a soft black cloth to ensure visual continuity of the rubber hand with the participant's arm (Fig. 1A).

Experimental paradigm. (A) Experimental design illustration of Visuomotor (VM) and Visuotactile (VT) stimulations, each divided for the Sync (synchronous coupling/stroking on both index fingers), Incong (synchronous coupling/stroking on the subject’s index finger and the rubber hand’s middle finger), and Async (coupling/stroking on both index fingers with a temporal delay) conditions. Red connecting lines in Visuomotor represent the mechanical connection between the subject’s index finger and the rubber hands index finger in Sync, the middle finger in Incong, or the experimenter’s finger for a delayed movement (Async). (B) Experimental procedure of a single run. In each run a single stimulation type (Visuotactile / Visuomotor) and condition (Sync / Incong / Async) was administered, after which the subject completed the Moving Rubber Hand illusion (MRHI) questionnaire that consists of 12 statements probing Sense of Agency and Body Ownership. The order of runs was randomized between subjects.

Experimental design

Participants underwent two types of sensorimotor stimulation: Visuotactile and Visuomotor. In the Visuotactile stimulation, as used in classical Rubber Hand illusion experiments to induce illusory Body Ownership83, participants were instructed to relax their hand while the experimenter brushed both the real and rubber hand with small brushes. In the Visuomotor stimulation, used in Moving Rubber Hand illusion experiments to elicit an illusion of Body Ownership and Sense of Agency over the rubber hand89,92,93, participants raised their index finger at a semi-regular rhythm of 1 Hz, which was practiced before the experiment. This movement resulted in a movement of the rubber hand by thin metal rod hidden inside the box. In both Visuotactile and Visuomotor stimulations, three different conditions were used. The brush strokes (i.e., Visuotactile) or active movement (i.e., Visuomotor) of the participant’s index finger was accompanied by either anatomically congruent and temporally synchronous stimulation of the rubber hand’s index finger (Sync), or anatomically incongruent and temporally synchronous stimulation of the rubber hand’s middle finger (Incong), or anatomically congruent and asynchronous stimulation with a 500 ms delay inserted between stimulation of the real and rubber hand (Async) (Fig. 1). In the Visuomotor Async condition, the metal rod was connected to the experimenter’s finger, allowing the experimenter to manipulate the rubber hand’s movement in a matter unknown to the participant. Each combination of stimulation type and condition was induced in a separate run lasting one minute, resulting in a total of six runs presented in a pseudorandomized order.

After each run, participants completed the Moving Rubber Hand illusion questionnaire93 which assesses their subjective experiences of Body Ownership and Sense of Agency. The questionnaire comprises 12 statements, including three statements referring to Body Ownership, three to Sense of Agency, three Body Ownership control statements, and three Sense of Agency control statements (see Supplementary Table S1 for the full list of statements). The control statements in the questionnaire do not capture the specific phenomenological experiences of Body Ownership or Sense of Agency, but rather have several similarities to the illusion-specific statements in general92. Each statement was rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from −3 “totally disagree” to + 3 “totally agree”, with 0 indicating “neutral”. Control and Psychedelic participants were presented with the statements on a computer screen and responded with a num-pad, while the Psychosis participants responded verbally.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JASP 0.16.3113 and R114. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess normality (p > 0.05). Since the data sets failed to meet the criteria for normal distribution, the appropriate non-parametric tests were applied. Friedman’s repeated measures ANOVA was used to estimate the main effects of Condition (Sync / Incong / Async) as a within-subjects factor, with a Pairwise Wilcoxon Rank sum test (Bonferroni corrected) as post-hoc. One-way Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA was used to estimate the main effects of Group (Control / Psychedelic / Psychosis) as a between-subjects factor, with Dunn test (Bonferroni corrected) as post-hoc. To examine whether the effect of Group is modulated by Condition type, we calculated the differences between all Condition scores and conducted a One-way Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA on these differentials115,116,117. For non-significant results of the Group factor, we performed a Bayesian Mann–Whitney test between Control and Psychedelic, and between Control and Psychosis, to assess the evidence’s strength of the null hypothesis. Specifically, we used a Bayes factor of exclusion. Briefly, BF exclusion was obtained using JASP, by comparing the evidence of models that included the factor of interest to the evidence of models that did not include the factor. Since there was no prior knowledge on the effect between groups, we used the default prior (Cauchy = 0.707) and reported the robustness of the findings (See supplementary Table S3) using a wide prior (Cauchy = 1.414) and a narrow prior (Cauchy = 0.353)118. The models that were compared were of similar complexity, including the same number of variables119. Thus, BF exclusion represents how likely it is to observe the data under models that exclude the factor compared to models that include this factor. BF values between 1 and 3, 3 and 10, and 10 and 30, were interpreted as anecdotal, moderate, and strong evidence for the hypothesis respectfully120. To examine if a condition induced an illusion of Body Ownership or Sense of Agency over the rubber hand, we conducted a Wilcoxon signed-rank test by comparing the participants’ ratings to 0 (i.e., neutral experience). Conversely, the control ratings were compared to 0 in the opposite direction using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test, to ensure all were rated negatively below zero. To estimate the difference in Body Ownership illusion strength between the Healthy group (Control and Psychedelic) and the Psychosis group, we performed a Mann–Whitney test. The illusion strength for each group was computed as the difference in Body Ownership subjective rating between Sync and Async conditions. The Sync and Async conditions were also compared using a paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test within groups. We used Spearman’s correlations to estimate the association between the strength of Sense of Agency and Body Ownership illusion in each simulation. Comparing illusion scores between recent users (within the last month) and past users (beyond the last month) revealed no significant differences in scores for any of the illusion conditions; hence, this aspect was not further analyzed.

Results

Psychedelic experience is associated with altered self-experiences

To examine reported differences in self-related experiences between the Control and Psychedelic groups, we compared the mean scores of their statements across sections of the self-experience questionnaire Fig. 2. The Psychedelic group’s mean in the EDI statements (M = 7.28, SD = 2) was significantly higher than the Control group’s mean (M = 3.85, SD = 1.92) (W = 68, p < 0.0001). Similarly, in the MEQ statements, the Psychedelic group showed a higher mean (M = 8.27, SD = 1.65) than the Control group (M = 3.02, SD = 2.45) (W = 38, p < 0.0001; For the analysis of each question, see Supplementary Fig. S1 and Table S2). Additionally, in the CDS statements the Psychedelic group’s mean score (M = 5.33, SD = 1.99) was higher than the Control (M = 3.16, SD = 1.77) (W = 127, p < 0.001). These results support previous reports of the association between psychedelic experiences and changes in the sense of self26,27,29,121.

Psychedelic experience is associated with reported altered self-experiences. Statements scores were gathered from each questionnaire. (A) Scores for statements from Ego Dissolution Inventory (EDI). (B) Pahnke-Richards Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ). (C) Cambridge Depersonalization Scale (CDS). Gray ‘X’ at the boxplots represents the group’s mean. Asterisks indicate significance levels: ∗ p < 0.05; ∗ ∗ p < 0.01; and ∗ ∗ ∗ p < 0.001.

Reduced sense of agency during visuomotor stimulation in psychosis

As expected, Visuomotor stimulation induced an experience of Sense of Agency in the Sync condition (M = 1.81, SEM = 0.15, V = 2527, p < 0.001), the Incong condition (M = 0.85, SEM = 0.21, V = 2042, p < 0.001), where temporal coupling occurs, and was not significant in the Async condition (M = −0.18, SEM = 0.21, p > 0.05; see Fig. 3B). A main effect of Condition was found, (χ2 (2) = 52.4, p < 0.0001, Kendall’s W = 0.35), and post-hoc comparisons showed significant differences between all the combinations of conditions (p < 0.0001 for Sync vs. Async and p < 0.01 for the rest). Importantly, a main effect of Group was found (χ2 (2) = 6.68, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.02), and a post-hoc test revealed that this was driven by a significant difference between the Psychosis group and the Control group (p < 0.05) but was not significantly different between the Psychosis and Psychedelic groups (p = 0.057) and between the Psychedelic and Control groups (p = 0.567). A Bayesian analysis revealed moderate evidence supporting the lack of an effect between the Control and the Psychedelic groups (BF01 = 3.09). Despite lower Sense of Agency ratings of the Psychosis group, they were similarly affected by the different conditions in the Visuomotor stimulation, as can be seen by the lack of significant interaction between the Group and Condition factors (χ2 (2) = 1.54, p = 0.46). Notably, all the control statements ratings were negatively rated (p < 0.0001; Bonferroni Corrected). Thus, the Psychosis group showed reduced Sense of Agency compared to the Control group in the Visuomotor stimulation yet were comparably impacted by the modulation of anatomical congruence and temporal synchrony (Fig. 3B).

Behavioral Ratings. (A) Rating of Body Ownership in Visuomotor stimulation. (B) Ratings of Sense of Agency in Visuomotor stimulation (C) Ratings of Body Ownership in Visuotactile stimulation. (D) Ratings of Sense of Agency in Visuotactile stimulation. Gray ‘X’ at the boxplots represents the group’s mean.

Reduced body ownership during visuomotor stimulation in psychosis

As expected, Visuomotor stimulation induced an experience of Body Ownership in the Sync condition (M = 0.4, SEM = 0.21, V = 1665, p < 0.05), and a lower and non-significant in the Incong (M = −0.89, SEM = 0.19, V = 606, p = 1), and Async (M = −1.09, SEM = 0.2, V = 452, p = 1) conditions (Fig. 3A). A main effect of Condition was found (χ2 (2) = 39.3, p < 0.001, Kendall’s W = 0.26), and post-hoc comparisons showed significant differences between Sync vs. Async and Sync vs. Incong (p < 0.0001) and were not significant for the Incong vs. Async (p = 1). The main effect of Group was not significant (χ2 (2) = 1.34, p = 0.5). Notably, conditions affected the groups differently, as evidenced by a significant interaction between Condition and Group factors (χ2 (2) = 10.8, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.12). This interaction was driven by the lack of Body Ownership experience for the Psychosis group in the Sync condition (i.e., group’s mean is below 0). Importantly, the illusion strength of the Healthy group (Psychedelic and Control) was higher than the Psychosis group (Healthy: M = 2, SEM = 0.25; Psychosis: M = 0.52, SEM = 0.33; W = 916, p < 0.001). Additionally, a pairwise comparison between the typical difference of Sync and Async conditions was only significant in the Control (W = 252; p < 0.001) and Psychedelic (W = 290; p < 0.001) groups but was not significant in the Psychosis group (W = 107; p = 0.07). Nonetheless, a Bayesian analysis revealed moderate evidence supporting the lack of a group difference (main effect) between the Control and the Psychedelic groups (BF01 = 3.34) and between the Control and Psychosis groups (BF01 = 3.12). Notably, all the control statements ratings were negatively rated (p < 0.0001; Bonferroni Corrected). This lack of difference in the Sync and Async conditions, and diminished experience of Body Ownership illusion compared to the Healthy group, further supports our finding that the Psychosis group have impaired experience of Body Ownership under Visuomotor stimulation.

Visuotactile stimulation induced similar body ownership across groups

The Visuotactile stimulation is similar to the classic Rubber Hand illusion, which is characterized by inducing Body Ownership over the rubber hand. As expected, the participants experienced Body Ownership over the rubber hand in the Sync condition (M = 0.97, SEM = 0.22, V = 2107.5, p < 0.001). The Body Ownership ratings were non-significant and gradually declined in the Incong (M = −0.03, SEM = 0.22, V = 1282, p = 0.49), and Async (M = −0.91, SEM = 0.19, V = 579, p = 1) conditions (Fig. 3C). This was supported by a significant main effect of Condition (χ2 (2) = 44.2, p < 0.0001, Kendall’s W = 0.29), and post-hoc comparisons which showed significant differences between all possible combinations of conditions (p < 0.0001 for Sync vs. Async and p < 0.01 for the rest). Comparing Body Ownership between groups, we did not find significant differences between Control, Psychedelic, and Psychosis groups across the different conditions. The main effect of Group was not significant (χ2 (2) = 1.35, p = 0.5). Finally, the interaction of Group and Condition was not significant (χ2 (2) = 5.58, p = 0.062, η2 = 0.05). A Bayesian analysis revealed anecdotal evidence supporting the lack of a difference between the Control and the Psychedelic groups (BF01 = 2.37) and moderate evidence between the Control and Psychosis groups (BF01 = 3.36). Notably, all the control statements ratings were negatively rated (p < 0.0001; Bonferroni Corrected). Thus, no significant differences between the Psychosis, Psychedelic and Control groups were found in the Visuotactile induction of illusory Body Ownership (Fig. 3C) and moderate evidence against such differences was present.

Visuotactile stimulation did not induce sense of agency across groups

In general, the Visuotactile stimulation did not induce Sense of Agency experience over the rubber hand (Sync: M = −0.87, SEM = 0.21, V = 743, p = 1; Incong: M = −1.33, SEM = 0.18, V = 345, p = 1; Async: M = −1.85, SEM = 0.16, V = 154, p = 1; see Fig. 3D). A main effect of Condition was found (χ2 (2) = 21, p < 0.0001, Kendall’s W = 0.14). A post-hoc comparisons showed significant differences between the Sync vs. Async (p < 0.05) and nonsignificant for the rest (p > 0.05). The main effect of the Group was not significant (F(χ2) = 2.49, p = 0.28). Moreover, a Bayesian analysis revealed moderate evidence supporting the lack of a difference between the Control and the Psychedelic groups (BF01 = 3.12) and between the Control and Psychosis groups (BF01 = 2.56). A significant interaction between Group and Condition was found (χ2 (2) = 6.95, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.06). However, as mean ratings were below zero, we do not interpret this as inducing a Sense of Agency. All the control statements ratings were negatively rated (p < 0.0001; Bonferroni Corrected). Thus, in the absence of active movement, no experience of Sense of Agency over the rubber hand was formed, while the effect of condition was differently modulated between groups.

Positive correlation between body ownership and sense of agency

We wanted to determine whether Body Ownership experience was correlated with Sense of Agency experience in both simulations (Visuomotor and Visuotactile). To examine it we calculated the subtraction between Sync and Async for Body Ownership and Sense of Agency for each stimulation. The differences from the subtraction represent the Body Ownership and Sense of Agency illusion strength. Body Ownership and Sense of Agency illusions in Visuomotor were significantly correlated (r = 0.34, p < 0.01; see Fig. 4A). Likewise, Body Ownership and Sense of Agency illusions in Visuotactile were also significantly correlated (r = 0.51, p < 0.001; see Fig. 4B). These results stand with the idea that when one experiences Sense of Agency over the rubber hand, one also tends to experience Body Ownership over the rubber hand.

Discussion

The current study aimed at experimentally comparing how the bodily self is impacted in populations with modulations of the sense of self driven by psychotic or psychedelic experiences. Using the Moving Rubber hand Illusion, we tested both Body Ownership and the Sense of Agency in these populations. Our study revealed several interesting findings. First, as expected all populations showed modulations of Body Ownership using the classical Visuotactile stimulation. Second, the Psychosis group showed a reduced Sense of Agency during Visuomotor stimulation. Third, in the Control and Psychedelic groups, synchronous Visuomotor stimulation induced Body Ownership, which was absent in the Psychosis group. Finally, while the Psychedelic group reported altered self-experiences, we found no evidence for lasting modulations of the bodily self in this group.

As expected, synchronous Visuotactile stimulation induced illusory BO over the rubber hand. No significant differences were found between the Control, Psychedelic, and Psychosis groups and Bayesian analysis revealed moderate (i.e., Control vs. Psychosis) and anecdotal (i.e., Control vs. Psychedelic) evidence against such differences. This is in line with previous experimental and meta-analytical data showing no differences between Control and Psychosis groups in multisensory Body Ownership processing97. Similarly, this suggests that psychedelic experiences which often include striking modification of the phenomenological experiences of Body Ownership29,100,121, do not cause long-lasting alterations of multisensory bodily processing.

Previous theoretical and experimental work has highlighted abnormal Sense of Agency and predictive sensorimotor mechanisms as a central impairment across the schizophrenia spectrum22,48,122,123,124,125. For example, irregularities in Sense of Agency attribution have been shown in neurotypical individuals with high psychotypical scores126,127 and even in healthy individuals with a genetic propensity for schizophrenia38. In acute psychosis abnormalities in Sense of Agency processing are pronounced with both low accuracy in judgments and aberrant meta-cognition e.g.,33,34,94. Indeed, in a recent study embodied agency judgments allowed to classify psychotic participants with a high degree of accuracy34. The current results show reduced feeling of agency in the Psychosis group across all conditions indicating that they were affected by the conditions but had diminished sensation of control over the movements. This finding is in line with the passivity experiences in schizophrenia, which involve a reduction in Sense of Agency128,129,130. Furthermore, previous studies using body illusions, revealed that individuals on the schizophrenia spectrum experience a reduction in Sense of Agency similar to healthy individuals when exposed to Visuotactile or Visuomotor asynchronous stimulations, as evidenced by decreased Sense of Agency compared to synchronous stimulations128,131,132.

Synchronous Visuomotor stimulation also induced sensations of Body Ownership in the Control and Psychedelic groups but not the Psychosis group. Several studies have shown that Sense of Agency and Body Ownership are often correlated89,92,93, suggesting that they impact each other. Reduced Body Ownership during synchronous Visuomotor stimulation suggests that aberrant sensations of bodily self in psychosis may stem not from deficits in Body Ownership processing per se 97 but rather from reduced Sense of Agency which in turn impacts the feeling of ownership over body parts. Thus, while the Psychosis group showed typical Body Ownership and Sense of Agency in the Visuotactile conditions, these experiences were reduced specifically in Visuomotor conditions. This result joins previous evidence that the experience of the bodily self is disrupted in psychosis patients. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that these altered bodily experiences in psychosis patients are not a global impairment, but rather related to aberrant processing of volitional actions33,34,48,128,133.

Importantly, our findings highlight that while psychedelic experiences are associated with dramatic changes in the sense of self, including the bodily self29,100, these were not associated with experimentally induced changes in Body Ownership or Sense of Agency. In fact, across all experimental conditions the Psychedelic group’s results were nearly identical to those of the Control group. This finding is especially salient considering the clear differences in subjective experiences of modifications of the self between these groups (See Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S2). This suggests that while some changes to the sense of self induced by psychedelic experiences are retained at explicit levels of the self-model, fundamental sensorimotor processing of the bodily self is not altered in an enduring manner. Thus, our data provide evidence against psychotomimetic approaches to psychedelic experiences at least for bodily self-processing, in such that the Psychosis and Psychedelic groups showed no similarities in their results.

While considering that this is a novel study which must be replicated, we note several interesting implications arising from our findings. First, no evidence for modulations of the bodily self were shown in the psychedelic group. This suggests that long lasting changes in the sense of self are not evident at the level of the bodily self. Furthermore, psychosis patients showed atypical bodily self only in conditions including volitional action. This implicates Sense of Agency and action related processing as the primary mechanisms driving abnormal sense of bodily self in psychosis34,97,134. These findings may guide future studies in psychedelics to focus on higher levels of self-related processing e.g.,9,135, while targeting volitional action as a critical subject in the study of psychosis 136,137,138.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations which should be addressed. Due to the age limits of the population at the mental health center, the psychotic group was on average older than the other groups. Nonetheless, age differences were previously not found to affect the illusion strength139. Since the experiment was conducted in a male only ward of the Beer Yaacov-Ness Ziona mental health center, the Psychosis group consisted only of men. While Psychosis participants were screened for current or previous substance addictions, and none had a history of substance induced psychosis, we didn’t specifically inquire about psychedelic use. It is thus possible that some of these patients had previously experienced psychedelics. Furthermore, due to time constraints as well as the limited reliability of self-report questionnaires in psychosis we opted to assess the sense of self using the PANSS in this group. This prevented direct comparisons of questionnaire scores with the other groups. We didn’t include a passive movement condition in this study as we had a limited duration for our experiment with the psychosis group. This condition could have allowed additional insight into the effects of volitional action on the sense of self e.g.,92,93. Additionally, we didn’t collect proprioceptive drift measures, which have often been used as an implicit measure of the Rubber Hand illusion e.g.,92,93. As recent studies have found dissociations between proprioceptive drift and body ownership measurements140,141,142,143,144 and given the time limitations with the clinical cohort we decided not to include this measure in the design. Finally, due to ethical and experimental limitations, we could not collect psychedelic participants in the acute stage of the psychedelic experience, limiting any inferences regarding their acute effects. Further studies are needed to explore how different psychedelic compounds impact the sense of self, during and after the psychedelic experience.

Conclusions

Our study shows that psychosis impacts the bodily self with diminished agency and body ownership during volitional actions. Contrarily, while substantial psychedelic use was associated with reported enduring changes in the experience of self, it showed no impact on processing of the bodily self. Our results suggest that even considerable psychedelic use doesn’t alter multisensory bodily processing underlying the sense of self, but may manifest changes in more explicit, narrative models of the self.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Blanke, O. & Metzinger, T. Full-body illusions and minimal phenomenal selfhood. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13, 7–13 (2009).

De Vignemont, F. Mind the body: An exploration of bodily self-awareness. (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Limanowski, J. & Blankenburg, F. Minimal self-models and the free energy principle. Front. Human Neurosci. 7, (2013).

Metzinger, T. Being no one: The self-model theory of subjectivity. (mit Press, 2004).

Salomon, R. The assembly of the self from sensory and motor foundations. Soc. Cogn. 35, 87–106 (2017).

Seth, A. K. & Tsakiris, M. Being a Beast Machine: The Somatic Basis of Selfhood. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 969–981 (2018).

Blanke, O. Multisensory brain mechanisms of bodily self-consciousness. Nat Rev Neurosci 13, 556–571 (2012).

Carhart-Harris, R. L. & Friston, K. J. The default-mode, ego-functions and free-energy: a neurobiological account of Freudian ideas. Brain 133, 1265–1283 (2010).

Peer, M., Salomon, R., Goldberg, I., Blanke, O. & Arzy, S. Brain system for mental orientation in space, time, and person. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 11072–11077 (2015).

Qin, P., Wang, M. & Northoff, G. Linking bodily, environmental and mental states in the self—A three-level model based on a meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 115, 77–95 (2020).

Seghezzi, S., Giannini, G. & Zapparoli, L. Neurofunctional correlates of body-ownership and sense of agency: A meta-analytical account of self-consciousness. Cortex 121, 169–178 (2019).

Seth, A. K. Interoceptive inference, emotion, and the embodied self. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 17, 565–573 (2013).

Tsakiris, M. My body in the brain: A neurocognitive model of body-ownership. Neuropsychologia 48, 703–712 (2010).

Blanke, O. et al. Neurological and robot-controlled induction of an apparition. Curr. Biol. 24, 2681–2686 (2014).

Nour, M. M. & Carhart-Harris, R. L. Psychedelics and the science of self-experience. Br. J. Psych. 210, 177–179 (2017).

Waters, F. & Fernyhough, C. Hallucinations: A systematic review of points of similarity and difference across diagnostic classes. Schizophr Bull 43, 32–43 (2017).

Carhart-Harris, R. Waves of the unconscious: the neurophysiology of dreamlike phenomena and its implications for the psychodynamic model of the mind. Neuropsychoanalysis 9, 183–211 (2007).

Carhart-Harris, R. L. et al. The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, (2014).

Corlett, P. R., Frith, C. D. & Fletcher, P. C. From drugs to deprivation: a Bayesian framework for understanding models of psychosis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 206, 515–530 (2009).

Kircher, T. & Leube, D. Self-consciousness, self-agency, and schizophrenia. Conscious. Cognit. 12, 656–669 (2003).

Lebedev, A. V. et al. Finding the self by losing the self: Neural correlates of ego-dissolution under psilocybin. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36, 3137–3153 (2015).

Leptourgos, P. & Corlett, P. R. Embodied predictions, agency, and psychosis. Front. Big Data 3, 27 (2020).

Sass, L. A. & Parnas, J. Schizophrenia, consciousness, and the self. Schizophr. Bull. 29, 427–444 (2003).

González-Maeso, J. & Sealfon, S. C. Psychedelics and schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci. 32, 225–232 (2009).

Vollenweider, F. X., Vollenweider-Scherpenhuyzen, M. F. I., Bäbler, A., Vogel, H. & Hell, D. Psilocybin induces schizophrenia-like psychosis in humans via a serotonin-2 agonist action. NeuroReport 9, 3897 (1998).

Aday, J. S., Mitzkovitz, C. M., Bloesch, E. K., Davoli, C. C. & Davis, A. K. Long-term effects of psychedelic drugs: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 113, 179–189 (2020).

Amada, N., Lea, T., Letheby, C. & Shane, J. Psychedelic experience and the narrative self: an exploratory qualitative study. J. Conscious. Stud. 27, 6–33 (2020).

Milliere, R., Carhart-Harris, R. L., Roseman, L., Trautwein, F.-M. & Berkovitz-Ohana, A. Psychedelics, meditation, and self-consciousness. Front. Psychol. (2018).

Millière, R. Looking for the Self: Phenomenology, neurophysiology and philosophical significance of drug-induced ego dissolution. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, (2017).

Tagliazucchi, E. et al. Increased global functional connectivity correlates with LSD-induced ego dissolution. Curr. Biol. 26, 1043–1050 (2016).

Nour, M. M., Evans, L., Nutt, D. & Carhart-Harris, R. L. Ego-Dissolution and Psychedelics: Validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10, (2016).

Haggard, P., Martin, F., Taylor-Clarke, M., Jeannerod, M. & Franck, N. Awareness of action in schizophrenia. NeuroReport 14, 1081–1085 (2003).

Hauser, M. et al. Altered sense of agency in schizophrenia and the putative psychotic prodrome. Psych. Res. 186, 170–176 (2011).

Krugwasser, A. R., Stern, Y., Faivre, N., Harel, E. V. & Salomon, R. Impaired sense of agency and associated confidence in psychosis. Schizophrenia 8, 32 (2022).

Nelson, B. et al. A disturbed sense of self in the psychosis prodrome: linking phenomenology and neurobiology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 33, 807–817 (2009).

Parnas, J. Self and schizophrenia: a phenomenological perspective. Self Neurosci. Psych. 217–241 (2003).

Parnas, J., Handest, P., Jansson, L. & Sæbye, D. Anomalous subjective experience among first-admitted schizophrenia spectrum patients: empirical investigation. PSP 38, 259–267 (2005).

Salomon, R. et al. Agency Deficits in a Human Genetic Model of Schizophrenia: Insights From 22q11DS Patients. Schizoph. Bull. (2021).

Parnas, J. & Zandersen, M. Self and schizophrenia: current status and diagnostic implications. World Psych. 220–221 (2018).

Schneider, M. et al. Comparing the neural bases of self-referential processing in typically developing and 22q11. 2 adolescents. Dev. Cognit. Neurosci. 2, 277–289 (2012).

Vaskinn, A., Ventura, J., Andreassen, O. A., Melle, I. & Sundet, K. A social path to functioning in schizophrenia: From social self-efficacy through negative symptoms to social functional capacity. Psych. Res. 228, 803–807 (2015).

Campbell, J. Schizophrenia, the space of reasons, and thinking as a motor process. Monist 82, 609–625 (1999).

Gallagher, S. Self-reference and schizophrenia: A cognitive model of immunity to error through misidentification. Exploring the self: Philosophical and psychopathological perspectives on self-experience 203–239 (2000).

Schneider, K. Clinical psychopathology. (Grune & Stratton, 1959).

Frith, C. The positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia reflect impairments in the perception and initiation of action. Psychol. Med. 17, 631–648 (2009).

Salomon, R. et al. Agency deficits in a human genetic model of schizophrenia: insights from 22q11DS patients. Schizoph. Bull. 48, 495–504 (2022).

Ford, J. M., Palzes, V. A., Roach, B. J. & Mathalon, D. H. Did I do that? Abnormal predictive processes in schizophrenia when button pressing to deliver a tone. Schizoph. Bull. sbt072 (2013).

Salomon, R. et al. Sensorimotor induction of auditory misattribution in early psychosis. Schizoph. Bull. 46, 947–954 (2020).

Ehrsson, H. H. The Concept of Body Ownership and Its Relation to Multisensory Integration. (2012).

Gallagher, S. Dynamic models of body schematic processes. Adv. Conscious. Res. 62, 233 (2005).

Tsakiris, M., Hesse, M. D., Boy, C., Haggard, P. & Fink, G. R. Neural signatures of body ownership: a sensory network for bodily self-consciousness. Cerebral Cortex 17, 2235–2244 (2007).

Blakemore, S. & Frith, C. Self-awareness and action. Curr. Op. Neurobiol. 13, 219–224 (2003).

David, N., Newen, A. & Vogeley, K. The, “sense of agency” and its underlying cognitive and neural mechanisms. Conscious. Cognit. 17, 523–534 (2008).

Gallagher, S. Sense of agency and higher-order cognition: Levels of explanation for schizophrenia. Cognit. Semi. 1, 33–48 (2007).

Haggard, P. Conscious intention and motor cognition. Trends Cognit. Sci. 9, 290–295 (2005).

Krugwasser, A. R., Harel, E. V. & Salomon, R. The boundaries of the self: The sense of agency across different sensorimotor aspects. J. Vis. 19, 14–14 (2019).

Synofzik, M., Vosgerau, G. & Newen, A. Beyond the comparator model: A multifactorial two-step account of agency. Conscious. Cognit. 17, 219–239 (2008).

Blanke, O., Slater, M. & Serino, A. Behavioral, neural, and computational principles of bodily self-consciousness. Neuron 88, 145–166 (2015).

Chancel, M., Ehrsson, H. H. & Ma, W. J. Uncertainty-based inference of a common cause for body ownership. (2021).

Park, H.-D. & Blanke, O. Coupling Inner and Outer Body for Self-Consciousness. Trends Cognit. Sci. 23, 377–388 (2019).

Haggard, P. Sense of agency in the human brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 196–207 (2017).

Moore, J. W. What Is the Sense of Agency and Why Does it Matter? Front. Psychol. 7, (2016).

Blakemore, S., Wolpert, D. & Frith, C. Abnormalities in the awareness of action. Trends Cognit. Sci. 6, 237–242 (2002).

Wolpert, D. M., Ghahramani, Z. & Jordan, M. I. An internal model for sensorimotor integration. Science 269, 1880 (1995).

Carruthers, G. The case for the comparator model as an explanation of the sense of agency and its breakdowns. Conscious. Cognit. 21, 30–45 (2012).

Bays, P. M., Flanagan, J. R. & Wolpert, D. M. Attenuation of self-generated tactile sensations is predictive, not postdictive. PLoS Biol. 4, e28 (2006).

Kilteni, K., Houborg, C. & Ehrsson, H. H. Rapid learning and unlearning of predicted sensory delays in self-generated touch. eLife 8, e42888 (2019).

Moore, J. W., Wegner, D. M. & Haggard, P. Modulating the sense of agency with external cues. Conscious. Cognit. 18, 1056–1064 (2009).

Hughes, G. & Waszak, F. ERP correlates of action effect prediction and visual sensory attenuation in voluntary action. NeuroImage 56, 1632–1640 (2011).

Palmer, C. E., Davare, M. & Kilner, J. M. Physiological and perceptual sensory attenuation have different underlying neurophysiological correlates. J. Neurosci. 36, 10803–10812 (2016).

Shergill, S. S. et al. Modulation of somatosensory processing by action. Neuroimage (2012).

Van Elk, M., Salomon, R., Kannape, O. & Blanke, O. Suppression of the N1 auditory evoked potential for sounds generated by the upper and lower limbs. Biol. Psychol. 102, 108–117 (2014).

Press, C., Thomas, E. & Yon, D. Cancelling cancellation? Sensorimotor control, agency, and prediction. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 105012 (2022).

Reznik, D., Henkin, Y., Schadel, N. & Mukamel, R. Lateralized enhancement of auditory cortex activity and increased sensitivity to self-generated sounds. Nat. Commun. 5, 4059 (2014).

Yon, D., Gilbert, S. J., de Lange, F. P. & Press, C. Action sharpens sensory representations of expected outcomes. Nat. Commun. 9, 4288 (2018).

Farrer, C. et al. The angular gyrus computes action awareness representations. Cerebral Cortex 18, 254–261 (2008).

Salomon, R. et al. The insula mediates access to awareness of visual stimuli presented synchronously to the heartbeat. J. Neurosci. 36, 5115–5127 (2016).

Tsakiris, M., Haggard, P., Franck, N., Mainy, N. & Sirigu, A. A specific role for efferent information in self-recognition. Cognition 96, 215–231 (2005).

Farrer, C., Franck, N., Paillard, J. & Jeannerod, M. The role of proprioception in action recognition. Conscious. Cognit. 12, 609–619 (2003).

Kannape, O., Schwabe, L., Tadi, T. & Blanke, O. The limits of agency in walking humans. Neuropsychologia 48, 1628–1636 (2010).

Stern, Y., Ben-Yehuda, I., Koren, D., Zaidel, A. & Salomon, R. The dynamic boundaries of the Self: Serial dependence in the Sense of Agency. Cortex 152, 109–121 (2022).

Zaidel, A. & Salomon, R. Multisensory decisions from self to world. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 378, 20220335 (2023).

Botvinick, M. & Cohen, J. Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see [8]. Nature 391, 756 (1998).

Aimola Davies, A. M., White, R. C. & Davies, M. Spatial limits on the nonvisual self-touch illusion and the visual rubber hand illusion: Subjective experience of the illusion and proprioceptive drift. Conscious. Cognit. 22, 613–636 (2013).

Costantini, M. & Haggard, P. The rubber hand illusion: sensitivity and reference frame for body ownership. Conscious. Cognit. 16, 229–240 (2007).

Ma, K. & Hommel, B. The role of agency for perceived ownership in the virtual hand illusion. Conscious. Cognit. 36, 277–288 (2015).

Barnsley, N. et al. The rubber hand illusion increases histamine reactivity in the real arm. Curr. Biol. 21, R945–R946 (2011).

Ehrsson, H., Holmes, N. & Passingham, R. Touching a rubber hand: feeling of body ownership is associated with activity in multisensory brain areas. J. Neurosci. 25, 10564 (2005).

Harduf, A., Shaked, A., Yaniv, A. U. & Salomon, R. Disentangling the Neural Correlates of Agency, Ownership and Multisensory Processing. bioRxiv (2022).

Salomon, R., Lim, M., Pfeiffer, C., Gassert, R. & Blanke, O. Full body illusion is associated with widespread skin temperature reduction. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 7, (2013).

Wen, W., Yamashita, A. & Asama, H. The influence of action-outcome delay and arousal on sense of agency and the intentional binding effect. Conscious. Cognit. 36, 87–95 (2015).

Kalckert, A. & Ehrsson, H. H. Moving a Rubber Hand that Feels Like Your Own: A Dissociation of Ownership and Agency. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6, (2012).

Kalckert, A. & Ehrsson, H. H. The moving rubber hand illusion revisited: Comparing movements and visuotactile stimulation to induce illusory ownership. Conscious. Cognit. 26, 117–132 (2014).

Frith, C. D. & Done, D. J. Experiences of alien control in schizophrenia reflect a disorder in the central monitoring of action. Psychol. Med. 19, 359–363 (1989).

Franck, N. et al. Defective recognition of one’s own actions in patients with Schizophrenia. Am. J. Psych. 158, 454–459 (2001).

Faivre, N. et al. Sensorimotor conflicts alter metacognitive and action monitoring. Cortex 124, 224–234 (2020).

Shaqiri, A. et al. Rethinking body ownership in schizophrenia: experimental and meta-analytical approaches show no evidence for deficits. Schizoph. Bull. 44, 643–652 (2018).

Carhart-Harris, R. Psychedelic drugs, magical thinking and psychosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 84, e1–e1 (2013).

Paparelli, A., Di Forti, M., Morrison, P. & Murray, R. Drug-Induced Psychosis: How to Avoid Star Gazing in Schizophrenia Research by Looking at More Obvious Sources of Light. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 5, (2011).

Ho, J. T., Preller, K. H. & Lenggenhager, B. Neuropharmacological modulation of the aberrant bodily self through psychedelics. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 108, 526–541 (2020).

Carhart-Harris, R. L. et al. Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging. PNAS 113, 4853–4858 (2016).

Moreno, J. L., Holloway, T., Albizu, L., Sealfon, S. C. & González-Maeso, J. Metabotropic glutamate mGlu2 receptor is necessary for the pharmacological and behavioral effects induced by hallucinogenic 5-HT2A receptor agonists. Neurosci. Lett. 493, 76–79 (2011).

Timmermann, C. et al. Human brain effects of DMT assessed via EEG-fMRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2218949120 (2023).

Bouso, J. C., Dos Santos, R. G., Alcázar-Córcoles, M. Á. & Hallak, J. E. C. Serotonergic psychedelics and personality: A systematic review of contemporary research. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 87, 118–132 (2018).

Knudsen, G. M. Sustained effects of single doses of classical psychedelics in humans. Neuropsychopharmacol. 48, 145–150 (2023).

Peled, A., Pressman, A., Geva, A. B. & Modai, I. Somatosensory evoked potentials during a rubber-hand illusion in schizophrenia. Schizoph. Res. 64, 157–163 (2003).

Thakkar, K. N., Nichols, H. S., McIntosh, L. G. & Park, S. Disturbances in body ownership in schizophrenia: evidence from the rubber hand illusion and case study of a spontaneous out-of-body experience. PLoS ONE 6, e27089 (2011).

Dummer, T., Picot-Annand, A., Neal, T. & Moore, C. Movement and the rubber hand illusion. Perception 38, 271 (2009).

Kammers, M., de Vignemont, F., Verhagen, L. & Dijkerman, H. C. The rubber hand illusion in action. Neuropsychologia 47, 204–211 (2009).

Laurin, A. et al. Self-consciousness impairments in schizophrenia with and without first rank symptoms using the moving rubber hand illusion. Conscious. Cognit. 93, 103154 (2021).

Sierra, M. & Berrios, G. E. The Cambridge Depersonalisation Scale: a new instrument for the measurement of depersonalisation. Psych. Res. 93, 153–164 (2000).

Griffiths, R. R., Richards, W. A., McCann, U. & Jesse, R. Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology 187, 268–283 (2006).

JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.16.3)[Computer software]. (2022).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019).

Hicks, C. R. Fundamental concepts in the design of experiments. https://philpapers.org/rec/HICFCI (1964).

Mead: The design of experiments: statistical principles... - Google Scholar. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The%20design%20of%20experiments&publication_year=1988&author=R.%20Mead.

Jenkinson, P. M. & Preston, C. New reflections on agency and body ownership: The moving rubber hand illusion in the mirror. Conscious. Cognit. 33, 432–442 (2015).

van Doorn, J. et al. The JASP guidelines for conducting and reporting a Bayesian analysis. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 28, 813–826 (2021).

van den Bergh, D. et al. A tutorial on conducting and interpreting a Bayesian ANOVA in JASP. L’Année psychologique 120, 73–96 (2020).

Lee, M. D. & Wagenmakers, E.-J. Bayesian Cognitive Modeling: A Practical Course. (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Preller, K. H. & Vollenweider, F. X. Phenomenology, Structure, and Dynamic of Psychedelic States. in Behavioral Neurobiology of Psychedelic Drugs (eds. Halberstadt, A. L., Vollenweider, F. X. & Nichols, D. E.) 221–256 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2016_459.

Fletcher, P. C. & Frith, C. D. Perceiving is believing: a Bayesian approach to explaining the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 48–58 (2008).

Frith, C. & Done, D. Experiences of alien control in schizophrenia reflect a disorder in the central monitoring of action. Psychol. Med. 19, 359–363 (2009).

Hohwy, J. The sense of self in the phenomenology of agency and perception. Psyche 13, 1–20 (2007).

Hur, J.-W., Kwon, J. S., Lee, T. Y. & Park, S. The crisis of minimal self-awareness in schizophrenia: A meta-analytic review. Schizoph. Res. 152, 58–64 (2014).

Asai, T., Sugimori, E. & Tanno, Y. Schizotypal personality traits and prediction of one’s own movements in motor control: What causes an abnormal sense of agency?. Conscious. Cognit. 17, 1131–1142 (2008).

Stern, Y., Koren, D., Moebus, R., Panishev, G. & Salomon, R. Assessing the relationship between sense of agency, the bodily-self and stress: four virtual-reality experiments in healthy individuals. J. Clin. Med. 9, 2931 (2020).

Graham-Schmidt, K. T., Martin-Iverson, M. T. & Waters, F. A. V. Self- and other-agency in people with passivity (first rank) symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizoph. Res. 192, 75–81 (2018).

Stripeikyte, G. et al. Fronto-temporal disconnection within the presence hallucination network in psychotic patients with passivity experiences. Schizoph. Bull. 47, 1718–1728 (2021).

Synofzik, M., Thier, P., Leube, D. T., Schlotterbeck, P. & Lindner, A. Misattributions of agency in schizophrenia are based on imprecise predictions about the sensory consequences of one’s actions. Brain 133, 262–271 (2010).

Germine, L., Benson, T. L., Cohen, F. & Hooker, C. I. Psychosis-proneness and the rubber hand illusion of body ownership. Psychiatry Res. 207, 45–52 (2013).

Graham, K. T., Martin-Iverson, M. T., Holmes, N. P., Jablensky, A. & Waters, F. Deficits in Agency in Schizophrenia, and Additional Deficits in Body Image, Body Schema, and Internal Timing, in Passivity Symptoms. Front. Psychiatry 0, (2014).

Maeda, T. et al. Reduced sense of agency in chronic schizophrenia with predominant negative symptoms. Psych. Res. 209, 386–392 (2013).

Salomon, R. et al. Agency deficits in a genetic model of schizophrenia: insights from 22Q11DS patients. Schizophr. Bull. (in press).

Axelrod, V., Rees, G. & Bar, M. The default network and the combination of cognitive processes that mediate self-generated thought. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 896 (2017).

Leptourgos, P. & Corlett, P. Embodied predictions, agency, and psychosis. Front. Big Data 3 (2020).

Poletti, M., Gebhardt, E. & Raballo, A. Corollary discharge, self-agency, and the neurodevelopment of the psychotic mind. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 1169–1170 (2017).

Poletti, M., Gebhardt, E., Kvande, M. N., Ford, J. & Raballo, A. Motor impairment and developmental psychotic risk: connecting the dots and narrowing the pathophysiological gap. Schizophr. Bull. 45, 503–508 (2019).

Palomo, P. et al. Subjective, behavioral, and physiological responses to the rubber hand illusion do not vary with age in the adult phase. Conscious. Cognit. 58, 90–96 (2018).

Rohde, M., Di Luca, M. & Ernst, M. O. The Rubber Hand Illusion: feeling of ownership and proprioceptive drift do not go hand in hand. PLoS ONE 6, e21659 (2011).

Makin, T. R., Holmes, N. P. & Ehrsson, H. H. On the other hand: dummy hands and peripersonal space. Behav. Brain Res. 191, 1–10 (2008).

Erro, R., Marotta, A., Tinazzi, M., Frera, E. & Fiorio, M. Judging the position of the artificial hand induces a “visual” drift towards the real one during the rubber hand illusion. Sci. Rep. 8, 2531 (2018).

Walsh, E. et al. Are you suggesting that’s my hand? the relation between hypnotic suggestibility and the rubber hand illusion. Perception 44, 709–723 (2015).

Tsakiris, M. & Haggard, P. Experimenting with the acting self. Cognit. Neuropsychol. 22, 387–407 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants who took part in the study. This study was supported by an Israeli Science Foundation personal grant (ISF 1169/17) to R.S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H and G.P collected and analyzed the data, and prepared the figures and tables. E.V.H, provided clinical supervision, assisted with data collection from the clinical group, and helped with conceptualization. A.H, G.P, Y.S and R.S wrote the manuscript. R.S provided supervision and acquired funding for the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Harduf, A., Panishev, G., Harel, E.V. et al. The bodily self from psychosis to psychedelics. Sci Rep 13, 21209 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47600-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-47600-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.