Abstract

There is a lack of epidemiological data on fascioliasis in Egypt regarding disease characteristics and treatment outcomes across different governorates. We aimed to identify the demographic, epidemiologic, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients diagnosed with fascioliasis in Egypt. Data on human fascioliasis were collected retrospectively from patients’ medical records in the period between January 2018 and January 2020. The study included 261 patients. More than 40% of enrolled patients were in the age group of 21–40 years old. Geographically, 247 (94.6%) were from Assiut Governorate with 69.3% were from rural areas. The most frequent symptoms were right upper quadrant pain (96.9%), and fever (80.1%). Eosinophilia was found in 250 cases (95.8%). Hepatic focal lesions were detected in 131 (50.2%); out of them 64/131 (48.9%) had a single lesion. All patients received a single dose of 10 mg/kg of triclabendazole, 79.7% responded well to a single dose, while in 20.3% a second ± a third dose of treatment was requested. After therapy, there was a reduction in leucocytes, Fasciola antibodies titer, eosinophilic count, bilirubin, and liver enzymes with an increase in hemoglobin level. According to our findings, a high index of suspicion should be raised in cases with fever, right upper abdominal pain, and peripheral eosinophilia, and further imaging workup is mandated to detect hepatic focal lesions. Prompt treatment by triclabendazole can serve as a standard-of-care regimen even for suspected cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than eighty countries throughout the globe have reported cases of fascioliasis, a zoonotic infection spreads by eating contaminated food1. This infection is challenging to contain due to its complex epidemiology. Two species of liver flukes, Fasciola hepatica, and Fasciola gigantica are responsible for this parasitic disease. Fasciola hepatica are found all over the world since their snail vectors are present everywhere, but Fasciola gigantica is limited to Africa and Asia2. Significant economic losses and expenditures are caused by fascioliasis infestation in cattle, including impaired fertility, decreased meat, milk, and wool production, cost of anthelmintic medications, reduced weight gain, and loss from death3. Around 17 million individuals are infected with Fasciola globally4,5,6,7, and cases of high pathogenicity, such as neurological and ophthalmological affections, result in long-lasting consequences and even death5. It is found in Oceania, Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Europe, the Caribbean, and parts of Latin America. In some areas where animal fascioliasis is found, human cases are uncommon or sporadic. In other areas, human fascioliasis is very common or hyperendemic4,7.

Additionally, Fasciola infection prevalence varies greatly among regions8,9,10. Rates of infection ranged from 0 to 68% among 2700 participants investigated by Esteban et al. in 24 communities distributed throughout a narrow region between La Paz and Lake Titicaca in the Bolivian Altiplano11. Additionally, Cabada et al. evaluated 2500 children in 26 neighboring towns in the Anta province in Peru and found infection rates ranging from 0 to 20%12. Fascioliasis has been reported to be reemerging and emerging in various African, Asian, and Middle Eastern nations, with Iran, Turkey, Egypt, and Vietnam being the main endemic countries13,14,15,16. Fasciola eggs have been detected in a mummy, confirming that human fascioliasis has existed since pharaonic times17. Human fascioliasis has been identified in almost all Delta governorates16,18. In the Behera Governorate, coprological studies have shown a very high prevalence ranging from 5.2 to 19.0%19. Egypt had a very high prevalence20,21,22, which suggests that earlier WHO reports may underestimate the real situation19. Humans are infected by many different sources, which vary according to countries, diet and traditions. Sources mainly include several vegetables, drinking of natural freshwater or combinations of both, transporting the infective stage of metacercaria23.

Effective preventative actions may be implemented with an understanding of the disease’s epidemiology and its determinants. This study was designed to identify the demographic, epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, radiological characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients diagnosed with human fascioliasis in two governorates of Egypt.

Materials and methods

Study design

The current study was a retrospective study.

Study sites

Endemic diseases clinic in Assiut Governorate and Endemic Diseases Departments at the Directorate of Health Affairs in Al-Behera, Egypt.

Study population

The study retrospectively included the medical records of patients diagnosed with fascioliasis from January 2018 to January 2020 as during this duration an outbreak of Fasciola infection occurred at Manfalout District in Assiut Governorate. The records of patients who didn’t meet the criteria of diagnosis of fascioliasis (peripheral eosinophilia, positive stool analysis for Fasciola ova (Kato Katz test), and/or positive anti-Fasciola antibody) were excluded from the study. Indirect Hemoagglutination assay was used for detection of Fasciola Antibody with a titer of 160 or more was considered to be positive.

Study tool and data collection

A structured data sheet was designed and included demographic data, baseline clinical data, laboratory and radiological investigations, treatment outcome. Patients were followed up for 3 months after treatment by clinical examination, laboratory, and radiological investigations. The Kato Katz test was used for microscopic stool examination of eggs detection.

Data was collected from 370 medical records; 315 records from Assiut and 55 from Al- Behera were included, with the exclusion of 109 records because of a deficiency of some relevant data (Supplementary Table 1).

Ethics considerations

Obtaining the approval of the proposal from the Ethics Committee at the Central Directorate of Research and Health Development and review in the Ministry of Health and Population study (Approval number: 5-2021/12 on 10 March 2021). Official permission was obtained to access data from the Endemic Diseases Department at the Directorates of Health Affairs in Assiut and Al-Behera Governorates. Privacy and confidentiality of all data were assured as data sheets were coded with numbers to maintain anonymity. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration’s ethical guidelines. As the study is retrospective, patients' consent was waived by the Ethics Committee at the Central Directorate of Research and Health Development and review in the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population study.

Data management and analysis

Data was collected and reviewed carefully to ensure data quality. Data entry, cleaning recording, and analysis were done using SPSS software version 26 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, US) for windows 10. Descriptive statistics were calculated as the mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed quantitative variables and as a median and interquartile range for non-parametric quantitative variables and as frequency and percentages for categorical variables. Paired t-test was used as the test of significance for normally distributed quantitative variables and Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for comparing the difference between variables before and after treatment. The correlation between variables was tested using the spearman correlation. Statistical significance was considered when p-value was ≤ 0.05 for all statistical tests.

Results

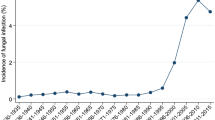

A total of 261 patient medical records were included, the mean age of the enrolled patients was 33.3 ± 17.9 years with a range between 5 and 75 years. More than half of the patients (55.2%) were females. The vast majority (94.6%) of cases were from Assiut Governorate. Rural residents represented 69.3% of the patients included. Regarding occupation, 37.2% were housewives, 30.7% were students, and 9.6% were farmers (Table 1). The majority of the patients (85.8%) came from Manfalout District, Assiut Governorate (Supplementary Fig. 1). Table 2 shows the baseline clinical manifestations of the included patients. The median duration of symptoms was 30 days with a range between 5 and 160 days. The most frequent symptoms were right upper quadrant pain (96.9%), fever (80.1%), and nausea (55.2%). Jaundice and dark urine were reported in 18 patients’ records (6.9%). As shown in Table 3, abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed in 32 (12.3%). But abdominal ultrasound was done for all patients. It was found that 23.4% of the patients had hepatomegaly, 24.5% had a single hepatic focal lesion and 25.7% had multiple lesions. The hepatic lesion was commonly observed in the right lobe (61.1%). Before treatment, 16 patients (6.1%) viable worms could be detected in the biliary system and were extracted with ERCP. Regarding the baseline laboratory data, Fasciola egg was detected in 5% of the examined stool as most of our patients were in the acute phase and some patients did not provide a stool specimen for analysis (children and a few adults), (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, eggs were measured in no case, so that a specific diagnosis whether by F. gigantica or F. hepatica could not be made”.

As shown in Table 4, at the baseline there was a marked increase in Fasciola antibody titer 640 (80–1280), eosinophils 3.6 (0–32.9), leucocytes 12 (2.3–45), platelets 304 (110–888), total bilirubin 2.6 (0.3–11), alanine transaminase 56 (14–311), and aspartate transaminase 59 (19.5–287) followed by a significant reduction in these parameters after therapy. On the other hand, there was no significant difference in hemoglobin level (p = 0.064) and albumin (p = 0.637).

Table 5 shows the treatment of the included patients and its outcome. For all patients, a single dose of 10 mg/kg of triclabendazole was described according to the treatment protocol of the Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population during the study period. The response was reported in 79.7% to a single dose, while in 20.3% a second ± a third dose of treatment was requested. Patients were followed up for 3 months following treatment by clinical evaluation, complete blood counts, Fasciola antibody, stool examination for Fasciola eggs and abdominal ultrasound. Clinical improvement was reported in 84.7% while 40 patients suffered from the persistence of abdominal pain (95.0%), nausea/vomiting (40.0%), fatigue (15.0%), and itching (2.5%). Fasciola egg in stool was detected in only three patients after therapy. As shown in Fig. 2A, there was a statistically significant positive weak correlation (r = 0.2) between the eosinophil count and Fasciola antibody titer before receiving the treatment and this correlation became of a moderate significance (r = 0.4) after the treatment (Fig. 2B).

Discussion

Fascioliasis is a major health problem, especially in limited-resource countries. In Egypt, hepatic fascioliasis was described as an endemic disease with a re-emerging pattern24,25. In the current study, female patients represented 55.2% compared to 44.8% of males. This is in agreement with a study by Curtale et al. that included over 21,000 children in Egypt and found that females had a significantly higher prevalence of fascioliasis than males26. A large study by Parkinson and others in the Bolivian Altiplano involving almost 8000 subjects found an insignificant association with sex8. Assiut Governorate, which is located in Upper Egypt, expressed the vast majority of our recruited cases and most of them were from rural communities, especially Manfalout District. This explains the occurrence of an outbreak of fascioliasis in this district during the study period which was reflected on the number of cases from Assiut, however this is not the true situation in Assiut or even in Egypt which is in concordance with the findings of Ramadan et al. and Hussieun et al.27,28. Most of the included patients were young which could be due to the exposure pattern of those who work on farms to be more liable to disease. This is in concordance with Mekky et al.24 who found a higher infection rate in males and in those who live in rural areas. Also, there may be a false-impression of bizarre distribution of the incidence all over the River Nile track. This could be explained by the location of the tertiary care Centers in areas with high ceiling hospitals like university institutes that work as a drainage area for such rare diseases.

In the present study, patients' age ranged from 5 to 75 years and about one-third of the included patients were students. This finding is in agreement with Parkinson and colleagues who reported that 70% of school children aged 8–11 years in the Bolivian Altiplano were affected by Fasciola infection8. Another study in agricultural communities in Peru showed that infected children had a mean age of 11 years in elementary school (10.2%) and high school (13.2%)12. In this study, more than two third of cases were rural residents (69.3%) because fascioliasis is a rural disease. Also, fascioliasis is considered as a zoonotic disease that tend to be presented in a high endemicity in a rural areas. This notion is obvious in our results as most of the patients (80 cases) were from the urban area explained by their origin from rural areas but resided in an urban area. Moreover, human fascioliasis is classified as plant- or food-borne fluke infections, often caused by ingestion of metacercariae attached to leaves that are eaten as vegetables29.

Several communities in low-income countries such as Egypt have a high prevalence of fascioliasis due to constant close contact with their livestock29. The problem of vegetables sold in uncontrolled urban markets is uncommon. The risks of traditional local dishes made from sylvatic plants are considered. Drinking contaminated water, beverages and juices, and washing of vegetables, fruits, tubercles and kitchen utensils with contaminated water are increasingly involved30.

More than 90% of cases complained of upper abdominal pain and fever. This finding was also reported in most of the published case scenarios regarding hepatic fascioliasis31. Hepatic focal lesions were reported in more than half of the patients and viable worm was detected in the biliary tree in 6.1% of cases before treatment. The presentation was variable due to variations in the incubation period that ranged from a few weeks to a few months with a wide range of disease severity4,32,33. Abdominal pain and fever are explained by the hepatic subcapsular invasion and or formation of small hepatic abscesses that occurred secondary to the immunologic reactions against the parasites4 and subcapsular nodule scan was detected on both sonography and CT scan34. Stool and blood techniques, the main tools for diagnosis in humans, have been improved for both patient and survey diagnosis35. Detection of Fasciola eggs in stool is a diagnostic test for fascioliasis35. In our study, the Kato Katz test was used for microscopic stool examination of eggs detection. In areas with a high prevalence and intensity of infection, the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests using the Kato Katz test, a quantitative microscopy test36,37. If used alone, the Kato Katz test might miss as many as one-third of infections. However, when combined with techniques that concentrate eggs, it becomes much more sensitive. Rapid sedimentation and spontaneous sedimentation are two sedimentation tests that are more sensitive than the Kato Katz36.

However, in this study, 5% of the examined records showed eggs in the stool before treatment. This could be owing to most patients in our study were in the acute phase and some patients did not do stool analysis for eggs (children and a few adults). This is in agreement with studies conducted by Ali et al. and Hussieun et al.28,38. Serodiagnosis of fascioliasis in human and animal species has been successfully carried out employing several antigenic fractions of Fasciola, purified antigens and recombinant antigens. Cathepsins L are the most frequently used target antigens for detecting anti-Fasciola antibodies39.

The presence of eosinophilia is a common laboratory finding to suspect parasitic infestation. In this study, there is a significant correlation between eosinophilia and Fasciola antibody titer before and after treatment. This is in agreement with the results of El Mekky et al. and Hussieun et al.24,28. All patients were treated with oral triclabendazole, and most cases responded well to a single dose of 10 mg/kg of triclabendazole. Criteria of cure include improvement of the clinical manifestations, decrease of eosinophils and anti-Fasciola antibodies, disappearance of the hepatic focal lesions and ascites, and regression of splenomegaly.

Triclabendazole is considered the drug of choice in treating human fascioliasis40. One or two doses of 10 mg/kg per dose separated by 12 to 24 h are recommended by the WHO37. In 2019, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a two-dose regimen for the treatment of acute and chronic fascioliasis in people aged 6 and older41. The WHO endorses extensive medication administration as a method of decreasing the prevalence of fascioliasis in people living in endemic areas. Vietnam, Peru, Egypt, and Bolivia have implemented various measures to contain the infection in humans8,12,37,42. The prevalence of fascioliasis in Egypt dropped from 6 to 1% after the country implemented a school and community-based screening and treatment program in endemic areas15. Mass treatment and use of triclabendazole at irregular intervals may result in the emergence of resistant parasites43. Only a few cases of triclabendazole resistance in humans have been reported44,45. However given that triclabendazole is the only very effective medication available, reports of resistance are concerning as published by Ramadan et al.27.

In spite of being the first Egyptian study conducted in two centers; one in Upper Egypt and the other in Lower Egypt, to describe the situation of human fascioliasis, this study may carry some limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small and may not reflect the actual incidence of the disease. The researchers recruited cases from patients’ records with overt clinical and/or imaging findings. Second, the study was a retrospective one that carries an inhered selection bias. These defects can be solved by targeting all records in the selected governorates and follow-up of the cases after treatment on a large scale.

Conclusion

In conclusion, human fascioliasis is not an uncommon disease, and a high index of suspicion should be raised in cases with fever, right upper abdominal pain, and peripheral eosinophilia. Further imaging workup is mandated to detect hepatic lesions. Prompt treatment by triclabendazole can serve as a standard-of-care regimen even for suspected cases.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Furst, T., Duthaler, U., Sripa, B., Utzinger, J. & Keiser, J. Trematode infections: Liver and lung flukes. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 26, 399–419 (2012).

Mas-Coma, S., Valero, M. A. & Bargues, M. D. Chapter 2. Fasciola, lymnaeids and human fascioliasis, with a global overview on disease transmission, epidemiology, evolutionary genetics, molecular epidemiology and control. Adv. Parasitol. 69, 41–146 (2009).

Cwiklinski, K., O’neill, S., Donnelly, S. & Dalton, J. A prospective view of animal and human Fasciolosis. Parasite Immunol. 38, 558–568 (2016).

CDC. Fasciola Vol. 2022 (CDC, 2018).

Mas-Coma, S., Agramunt, V. H. & Valero, M. A. Neurological and ocular fascioliasis in humans. Adv. Parasitol. 84, 27–149 (2014).

Mas-Coma, S., Valero, M. A. & Bargues, M. D. Climate change effects on trematodiases, with emphasis on zoonotic fascioliasis and schistosomiasis. Vet. Parasitol. 163, 264–280 (2009).

Rosas-Hostos Infantes, L. R. et al. The global prevalence of human fascioliasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 10, 20499361231185412 (2023).

Parkinson, M., O’Neill, S. M. & Dalton, J. P. Endemic human fasciolosis in the Bolivian Altiplano. Epidemiol. Infect. 135, 669–674 (2007).

Cabada, M. M. et al. Fascioliasis and eosinophilia in the highlands of Cuzco, Peru and their association with water and socioeconomic factors. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 91, 989–993 (2014).

Silva, A. E. P., Freitas, C. D. C., Dutra, L. V. & Molento, M. B. Correlation between climate data and land altitude for Fasciola hepatica infection in cattle in Santa Catarina, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 29, e008520 (2020).

Esteban, J. G., Flores, A., Angles, R. & Mas-Coma, S. High endemicity of human fascioliasis between Lake Titicaca and La Paz valley, Bolivia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93, 151–156 (1999).

Cabada, M. M. et al. Socioeconomic factors associated with fasciola hepatica infection among children from 26 communities of the Cusco region of Peru. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 99, 1180–1185 (2018).

Qureshi, A. W., Zeb, A., Mansoor, A., Hayat, A. & Mas-Coma, S. Fasciola hepatica infection in children actively detected in a survey in rural areas of Mardan district, Khyber Pakhtunkhawa province, northern Pakistan. Parasitol. Int. 69, 39–46 (2019).

Zoghi, S. et al. Human fascioliasis in nomads: A population-based serosurvey in southwest Iran. Infez Med. 27, 68–72 (2019).

Caravedo, M. A. & Cabada, M. M. Human fascioliasis: Current epidemiological status and strategies for diagnosis, treatment, and control. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 11, 149–158 (2020).

Lotfy, W. M. & Hillyer, G. V. Fasciola species in Egypt. Exp. Pathol. Parasitol. 6, 9–22 (2003).

Arjona, R., Riancho, J. A., Aguado, J. M., Salesa, R. & González-Macías, J. Fascioliasis in developed countries: A review of classic and aberrant forms of the disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 74, 13–23 (1995).

Haseeb, A. N., El-Shazly, A. M., Arafa, M. A. & Morsy, A. T. A review on fascioliasis in Egypt. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 32, 317–354 (2002).

Periago, M. V. et al. Very high fascioliasis intensities in schoolchildren from Nile Delta governorates, Egypt: The old world highest burdens found in Lowlands. Pathogens 10, 1210 (2021).

Esteban, J. G. et al. Hyperendemic fascioliasis associated with schistosomiasis in villages in the Nile Delta of Egypt. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 69, 429–437 (2003).

Ahmad, A. A. et al. New perspectives for fascioliasis in upper Egypt’s new endemic region: Sociodemographic characteristics and phylogenetic analysis of Fasciola in humans, animals, and lymnaeid vectors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16, e0011000 (2022).

Adarosy, H. A., Gad, Y. Z., El-Baz, S. A. & El-Shazly, A. M. Changing pattern of fascioliasis prevalence early in the 3rd millennium in Dakahlia Governorate, Egypt: An update. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 43, 275–286 (2013).

Mas-Coma, S., Bargues, M. D. & Valero, M. A. Human fascioliasis infection sources, their diversity, incidence factors, analytical methods and prevention measures. Parasitology 145, 1665–1699 (2018).

Mekky, M. A., Tolba, M., Abdel-Malek, M. O., Abbas, W. A. & Zidan, M. Human fascioliasis: A re-emerging disease in upper Egypt. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93, 76–79 (2015).

Hussein, A.-N.A. & Khalifa, R. M. A. Fascioliasis prevalences among animals and human in upper Egypt. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 22, 15–19 (2010).

Curtale, F. et al. Human fascioliasis infection: Gender differences within school-age children from endemic areas of the Nile Delta, Egypt. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101, 155–160 (2007).

Ramadan, H. K. et al. Evaluation of nitazoxanide treatment following triclabendazole failure in an outbreak of human fascioliasis in upper Egypt. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007779 (2019).

Hussieun, S. M. et al. Studies on sociodemography, clinical, laboratory and treatment of fascioliasis patients in Assiut hospitals, Assiut governorate, Egypt. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 52, 133–138 (2022).

Mas-Coma, S., Valero, M. A. & Bargues, M. D. Fascioliasis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 766, 77–114 (2014).

Angles, R., Buchon, P., Valero, M. A., Bargues, M. D. & Mas-Coma, S. One health action against human fascioliasis in the Bolivian Altiplano: Food, water, housing, behavioural traditions, social aspects, and livestock management linked to disease transmission and infection sources. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 1120 (2022).

Gell, J.M. & Graves, P.F. Case Study: 32-Year-Old Male Presenting with Right Lower Quadrant Abdominal Pain. In StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC., Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Peter Graves declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies, 2023).

Lalor, R. et al. Pathogenicity and virulence of the liver flukes Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola Gigantica that cause the zoonosis Fasciolosis. Virulence 12, 2839–2867 (2021).

Kaya, M., Beştaş, R. & Cetin, S. Clinical presentation and management of Fasciola hepatica infection: Single-center experience. World J. Gastroenterol. 17, 4899–4904 (2011).

Kim, T. K. & Jang, H. J. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the diagnosis of nodules in liver cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 3590–3596 (2014).

Mas-Coma, S., Bargues, M. D. & Valero, M. A. Diagnosis of human fascioliasis by stool and blood techniques: Update for the present global scenario. Parasitology 141, 1918–1946 (2014).

Lopez, M. et al. Kato-Katz and Lumbreras rapid sedimentation test to evaluate helminth prevalence in the setting of a school-based deworming program. Pathog. Glob. Health 110, 130–134 (2016).

World Health Organization. Report of the WHO Informal Meeting on use of Triclabendazole in Fascioliasis Control: WHO Headquarters, Geneva, Switzerland 17–18 October 2006 (World Health Organization, 2007).

Ali, M. N., Amin, M. A., Nada, M. S. & Abou-Elez, R. M. Fascioliasis in man and animals at sharkia province. Zagazig Vet. J. 42, 81–86 (2014).

Valero, M. A. et al. Assessing the validity of an ELISA test for the serological diagnosis of human fascioliasis in different epidemiological situations. Trop. Med. Int. Health 17, 630–636 (2012).

Fang, W., Chen, F., Liu, H. K., Yang, Q. & Yang, L. Comparison between albendazole and triclabendazole against Fasciola gigantica in human. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi 26, 106–108 (2014).

Zhang, X. et al. Application of PBPK modeling and simulation for regulatory decision making and its impact on US prescribing information: An update on the 2018–2019 submissions to the US FDA’s office of clinical pharmacology. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 60(Suppl 1), S160-s178 (2020).

Bui, T. D., Doanh, P. N., Saegerman, C. & Losson, B. Current status of fasciolosis in Vietnam: An update and perspectives. J. Helminthol. 90, 511–522 (2016).

Sargison, N. Diagnosis of triclabendazole resistance in Fasciola hepatica. Vet. Rec. 171, 151–152 (2012).

Winkelhagen, A. J., Mank, T., de Vries, P. J. & Soetekouw, R. Apparent triclabendazole-resistant human Fasciola hepatica infection, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18, 1028–1029 (2012).

Gil, L. C. et al. Resistant human fasciolasis: Report of four patients. Rev. Med. Chil. 142, 1330–1333 (2014).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND all authors have drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; AND all authors have approved the final version to be published; AND all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All persons who have made substantial contributions to the work reported in the manuscript, including those who provided editing and writing assistance but who are not authors, are named in the Acknowledgments section of the manuscript and have given their written permission to be named. If the manuscript does not include Acknowledgments, it is because the authors have not received substantial contributions from non-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibrahim, N., Abdel Khalek, E.M., Makhlouf, N.A. et al. Clinical characteristics of human fascioliasis in Egypt. Sci Rep 13, 16254 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42957-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-42957-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.