Abstract

Glycemic control is of paramount importance in care and management for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Poor glycemic control is a major health problem that greatly contributes to the development of diabetes related complications. This study aims to assess the prevalence of poor glycemic control and associated factors among outpatients with T2DM attending diabetes clinic at Amana Regional Referral Hospital in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania from December 2021 to September 2022. A face to face interviewer semi-structured questionnaire was administered during data collection. Binary logistic regression under multivariable analysis was used to determine the independent predictors of poor glycemic control. A total of 248 patients with T2DM were included in the analysis with mean age of 59.8 ± 12.1 years. The mean fasting blood glucose was 166.9 ± 60.8 mg/dL. The prevalence of poor glycemic control was 66.1% (fasting blood glucose > 130 mg/dL or < 70 mg/dL). Failure to adhere to regular follow-up (AOR = 7.53, 95% CI = 2.34–19.73, p < 0.001) and alcoholism (AOR = 4.71, 95% CI = 1.08–20.59, p = 0.040) were the independent predictors of poor glycemic control. The prevalence of poor glycemic control observed in this study was significantly high. Emphasis should be placed on ensuring that patients have regular follow-up for their diabetes clinics and they should also continue modifying some of lifestyle behaviors including refraining from alcoholism, this can help them to have good glycemic control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic syndrome which is characterized by hyperglycemia that develops as a result of lack or deficit of insulin secretion or sometimes resistance to its function1. The long-standing effects of hyperglycemia are associated with long-term damage, dysfunction, and failure of different organs, especially the eyes, kidneys, nerves, heart, and blood vessels2,3. DM is a significant public health problem of concern globally which contributes to approximately 5 million deaths annually from related complications4,5. It is estimated that, over 422 million adults are living with DM worldwide and this number is expected to increase to about 439 million adults by 2030 and 642 million by 20406. The incidence of DM is increasing at a high rate globally, and approximately 80% of patients with DM reside in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs)7. Its negative impact is highest in resources-limited countries, where screening and access to care and treatment continue to be challenging for the fragile health systems available in place8.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) accounts for almost 90% of all forms of DM9. T2DM is a heterogeneous group of disorders which develops as a result of impaired secretion of insulin and/or resistance which both result into hyperglycemia10. The incidence of DM as well as T2DM vary from one country and another globally. In the United Kingdom for example, T2DM is the most common chronic disease and its incidence is increasing and between 2018–2019, it accounted for approximately 90% for adults with chronic diseases11. The incidence of T2DM is escalating globally including in most of LMICs particularly those which are found in the sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) region12. In 2018, Mayega et al. reported that the incidence of T2DM in Uganda was significantly increasing and over 400,000 people were living with T2DM13. The incidence of T2DM in Sudan was 20% in a study which was conducted in 201914. Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) region, is one of the regions in the world with a large number of individuals living with DM and in 2019, approximately 54.8 million adults aged 20–79 were living with DM15. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) report of 2022, it was reported that the prevalence of T2DM among adults was 10.3% and a total of 2,884,000 adults were living with DM16.

Achievement of good glycemic control among patients with T2DM is of paramount importance in delaying and/or preventing early onset of diabetes related complications which are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Approximately, only 50% of diabetics worldwide achieve good glycemic control12 and in SSA, studies have shown majority of patients with T2DM have poor glycemic control. For example, in a study which was done in Ethiopia it was found that 74% of the patients with T2DM had poor glycemic control17. Also, in another study which was done in Uganda, the prevalence of poor glycemic control was found to be 84.3%18. In other two studies which were both done in Dar-es-salaam in 2014 reported prevalence of poor glycemic control among patients with T2DM of 69.7% and 64.4%19,20. In SSA, achieving good glycemic control as a result of proper management of diabetes faces many challenges including inadequate resources, lack of health priorities, inadequate funds for chronic disease management as well as low health insurance coverage and/or lack of health insurance21.

Both poor and good glycemic control in diabetics are usually predicted by different factors which may either modifiable or non-modifiable factors. For example, alcohol consumption which is a modifiable factor, is usually associated with failure of patients to achieving good glycemic control due to failure to exercise a number of beneficial actions including self-care and poor dietary intake, which both together contribute to poor glycemic control22. Studies have also reported a positive association of old age and male gender with poor glycemic and among diabetics despite contradicting findings in the literature23,24.

The problem of poor or inadequate ability of patients with T2DM to control their blood sugar level in Tanzania has not been fully investigated. This contributes to failure of realizing how big is the problem and this may also lead to lack of priority for allocation of funds for tackling the problem in order to improve the quality of life of the patients through reduction of morbidity and mortality. Therefore, the current study aims to assess the prevalence of poor glycemic control and associated factors among outpatients with T2DM attending diabetes clinic at a regional referral hospital.

Methods

Study design, setting, and duration

This was a cross-sectional analytical hospital-based study. The study was conducted at Amana regional referral hospital (ARRH) in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania from December 2021 to September 2022. The hospital is located in Ilala municipal which is among the five municipals of the Dar-es-salaam city which is the largest business center of the country. The hospital provides treatment for approximately 43,800 patients per year of whom approximately 2080 usually attend the hospital for DM related treatments. Dar-es-salaam city is one of the highly populated cities in Tanzania with a significant number of adults who engage in substance use including alcoholism and smoking, which both are more likely to affect glycemic control for those with T2DM. In a recent study which was conducted in Dar-es-salaam, the reported prevalence of alcoholism and smoking was 31.3% and 6.3%, respectively25. Another study also reported prevalence of 17.2% and 8.7% among study subjects for alcoholism and smoking, respectively26.

Patients’ characteristics and recruitment procedure

We included outpatients with T2DM who were attending diabetes clinic and they agreed to sign written informed consent. All patients with T2DM that were not willing to sign written informed consent and those who were seriously ill were excluded from the analysis.

Sample size determination and sampling method

The sample size was calculated using the standard formula described by Kish Leslie considering prevalence for a single population: n = Z2 × p (100 − p)/e227 assuming standard normal variables (z score) of 1.96 at 95% confidence interval, margin error (e) of 5% and prevalence (p) of 75.8% of poor glycemic control which was reported in the study by Rwegerera GM in Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania in 201420. The total sample size obtained was 248 after considering attrition rate of 10%. Then the sample size of 248 was drawn from a study population of 480 subjects using lottery simple random sampling method. On average 20 patients could attended per week, out of whom up to 10 patients were sampled per week. Pieces of papers were cut and labeled “Yes” and “No” depending on the number of patients had attended. The pieces of papers were folded uniformly and placed in a container, which was covered tightly and shaken so as to mix them. Then the container was opened and every patient was asked to pick one piece of paper. Only those who picked a piece of paper labeled “Yes” were selected to participate in the study.

Definition of variables

Physical activity

Physical activity was defined as any action involving body movement that results from relaxation and contraction of muscles that uses energy stores28. In this study, physical activity was measured as it was done in the previous study29. Patients who reported to do physical activity in less than 30 min per session per day were considered to have mild physical activity and those who reported to have physical activity in more than 30 min per session per day had moderate physical activity, and patients who reported to have physical activity for more than 45 min per session per day were regarded having vigorous activity.

Adherence to dietary intake

Diet for patients with T2DM was defined as the diet comprising of small and frequent more or equal to 5 per day that contains fruits, vegetables, high fibers and whole grains and low in sugars30. Adherence to dietary intake was measured using 10 items whose responses were grouped on Likert scale with scores ranging from 0 to 20 in which responses “always”, “sometimes” and “never” were scored 2, 1, and 0, respectively as it was done previously31. Good adherence to dietary intake was considered for scores from 15 to 20, 10 to 15 partial adherence and less than 10 scores were considered non-adherence to dietary intake.

Glycemic control

Good glycemic control was defined as an average of three consecutive fasting blood glucose measurements between 80 and 130 mg/dL. Poor glycemic control was defined as patients who had average blood glucose measurements on three consecutive visits > 130 or < 70 mg/dL32. Blood glucose level was measured using a glucometer (ONETOUCH Select Simple, serial number SAKQN77Z, Zug-Switzerland).

Data collection and research instrument

Data were collected using a face to face interviewer administered semi-structured questionnaire which was adapted from a previous study particularly in measuring physical activity and adherence to dietary intake31. The questionnaire was divided into three parts: part 1 comprised sociodemographic characteristics (age of the patient, sex, education level, marital status, religion, residence, occupation, and income level), part II consisted of clinical characteristics (duration of T2DM, duration of treatment, route of medication, type of anti-diabetes, adherence to regular follow-up, complications, comorbidities, health insurance, and family history of T2DM, and part III included lifestyle behaviors (alcoholism, smoking, physical activity, and adherence to diabetes dietary intake).

Data collection was done by three researchers (I.F.D, J.J.Y and E.D.M). Validation of the adapted questionnaire was done by conducting a pre-test among 30 patients with T2DM from a different hospital within Ilala municipal in Dar-es-salaam. Data collection was done once per week when patients attended their diabetes clinic. Approximately, 10–20 min were spent during interview for every patient, and the process of interviewing patients was carried out in a secluded room for maintenance of privacy of the patients. Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75 for internal consistency of the validated questionnaire for evaluation of dietary adherence and physical activity was acceptable.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 25.0. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize both categorical and continuous variables in frequencies and percentages and mean ± standard deviation (SD), respectively. Inferential statistics involved the use of binary logistic regression analysis in determining the predictors of poor glycemic control. All variables with p < 0.2 in univariate analysis were fitted into multivariable analysis for controlling confounding factors. Odds ratios (ORs) at 95% confidence interval (CI) were determined for assessing predictability of the independent variables. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients and a copy has been kept by the corresponding author for future review by the Editor-In-Chief of the journal when requested.

Ethics and consent

This study was approved by the Ethical Research Committee of the University of Dodoma (reference: MA.84/261/02 dated 3rd November 2021). We also confirm that all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All study participants signed informed consent and confidentiality was maintained by anonymizing identification of the participants. All study participants signed written informed consent and agreed their anonymized data to be published.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients with T2DM

A total of 248 patients with T2DM were analyzed in the present study with response rate of 92.9%. The mean age of the patients was 59.8 ± 12.1 years (range 31–93 years). Majority 70.2% (174/248) of the patients were females and most 48.4% (120/248) of the patients were aged between 45 and 60 years. Over half 35.5% (88/248) of the patients had attained tertiary level of education and also over half 38.3% (98/248) were obese (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics of the patients with T2DM

The clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 2. Majority 68.5% (170/248) of the patients had more than 5 years since the time they were diagnosed with T2DM and over half 56.5% (140/248) of the patients were on treatment between 5 and 10 years since they were put on anti-T2DM medication. Also, majority 63.3% (157/248) of the patients reported to have no regular follow-up of their DM clinics. Additionally, almost half 49.2% (122/248) of the patients had diabetic complications and retinopathy was the most common complication which consisted of 40.2% (49/122) of all complications.

Lifestyle behaviors of the patients with T2DM

Majority 79.8% (198/248) of the patients in this study reported not to have a tendency of taking physical activity in their history of being diabetic. Also, over one-third 33.1% (82/248) of the patients were not adhering to the guidelines concerning diabetic diets (Table 3).

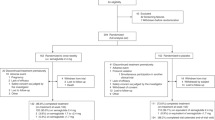

Prevalence of poor glycemic control

The statuses of glycemic control are shown in Fig. 1. The mean fasting blood glucose level was 166.9 ± 60.8 mg/dL (range 41.4–434.2 mg/dL). Majority 64.9% (161/248) of the patients had hyperglycemia and only 1.2% (3/248) had hypoglycemia, making a total of 66.1% (164/248) of patients with poor glycemic control in this study and the remaining 33.9% (84/248) patients had good glycemic control.

Predictors of poor glycemic control

In multivariable logistic regression analysis; age, sex, level of education, health insurance, level of income, comorbidities, adherence to regular follow-up, duration of treatment, taking alcohol, and physical activity had p < 0.2 in univariate analysis and with no multicollinearity problems, and therefore were fitted in multivariable logistic regression analysis using enter method. Two independent variables remained significantly associated with poor glycemic control: failure of adherence to regular follow-up (AOR = 7.53, 95% CI = 2.34–19.73, p < 0.001) and taking alcohol (AOR = 4.71, 95% CI = 1.08–20.59, p = 0.040) (Table 4).

Discussion

This study aims to determine the prevalence of poor glycemic control and the factors that are significantly associated with increasing or decreasing levels of fasting blood glucose in a sample of Tanzanian patients with T2DM living in the Dar-es-salaam region. The findings have shown that, the vast majority of the patients that were assessed had poor glycemic control. It was also found that, failure to adhere to regular follow-up and alcoholism were the independent factors that was were significantly associated with poor glycemic control.

The vast majority of patients in this study had poor glycemic control. Similar high percentages of poor glycemic control of 69.7%, 64%, and 67.1% were reported in studies done Tanzania by Kamuhambwa et al.19, Hoffmeister et al.33, and Rwegerera20, respectively. Other studies done in Guinea and Cameroon34, Northern Ethiopia17, and South-Western Ethiopia35 reported poor glycemic control of 74%, 66.8%, and 72.7%, respectively, which are higher compared with the prevalence of poor glycemic control observed in the present study.

The prevalence of poor or suboptimal glycemic control among patients with T2DM from studies done in LMICs is higher compared with the one observed in most studies which have been reported in developing countries. For example, in the two studies which were done by Temma et al.36 and Matsumura et al.37 in Japan. The studies reported prevalence of poor glycemic control among patients with T2DM of 59.3% and 46.8%, respectively. These percentages of poor glycemic control are lower than that found in the present study and also other previous studies which were conducted in LMICs. In other studies which were done in Croatia38, Colombia39, and Thailand40 also reported relatively low prevalence of poor glycemic control of 58.8%, 52.7%, and 54.8%, respectively.

The discrepancy in prevalence of poor glycemic control among patients with T2DM reported in different areas may be based on different factors. Improved health systems including care for DM and good knowledge among patients and the general population regarding diseases such as DM observed among individuals in developed countries contribute to the improvement in control of blood sugar levels41,42. Fragile health systems associated with care of diabetes43, lack of political will to the engage the communities in improvement of health issues as well as lack of knowledge towards glycemic control among patients with diabetes in LMICs44; all account for the reported significantly high prevalence of poor glycemic control in most LMICs.

The difference in the tests used to measure glycemic control could also explain the variation in the prevalence of glycemic control. For example, use of fasting blood glucose test to measure blood glucose levels is more likely to give different results from results which may be produced when glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) test if used. Also, it has been reported that, the use of different cut-off points when using HbA1c test in measuring blood glucose level may lead to the variation in prevalence of poor glycemic control. For instance, some studies considered HbA1c ≥ 7%, 8% and 7% as cut-off points for patients to be considered to have poor glycemic control45.

Regarding factors associated with poor glycemic control in this study, we observed that lack of adherence to regular follow-up among patients was significantly associated with poor glycemic control. Patients who had irregular follow-up were almost 8 times more likely to have poor glycemic control compared to patients with adherence to regular follow-up. This is similar to the findings in the studies of Zhao et al.46 and Asao et al.47 in which it was also observed that, patients with diabetes who had optimal number of hospital visits for DM clinics was associated with good glycemic control and good quality of life. Furthermore, Yigazu et al.48 and Ramirez et al.49 also reported that, patients with T2DM who had regular follow-up had good glycemic control compared to patients that did not have regular follow-up.

The benefits of having regular follow-up among patients with DM depend on the condition of the patient. For patients with controlled blood sugar, the frequency of follow-up does not help in further improving the clinical outcomes of the patients50. However, patients with T2DM whose glycemic control is suboptimal or poor, are more likely to improve when they maintain regular follow-up for their diabetes clinics over a period of time51. Therefore, it is important for patients with diabetes to have regular follow-up during diabetes clinics.

In this study, taking alcohol was associated with high odds for poor glycemic control. The odds for poor glycemic control among patients who were taking alcohol were significantly higher than in patients who were non-alcoholic. Other studies have also reported a positive association between poor glycemic control with alcohol intake among diabetics. Salama et al. and Abdissa et al. reported that alcohol intake was associated with poor glycemic control52,53. Alcohol intake is detrimental particularly for vulnerable people such as those with diabetes, which usually affects the ability of the patients to practice self-care for themselves as well as affecting vital body organs54. Studies have shown that, excess alcohol intake, particularly in patients with DM can lead to accumulation of certain acids including acetic acid and acetaldehyde in the blood circulation which leads to lethal complications including damage to the organs, dehydration, and increased blood pressure54,55,56. Additionally, alcohol intake can worsen diabetes-related medical complications, such as disturbances in fat metabolism, nerve damage, and eye disease53,55.

Alcohol consumption for patients with DM is associated with decreased food intake57 and it is also linked with reduced desire to adhere to dietary guidelines58, which both are more likely to impair glycemic control. Furthermore, it has also been shown that alcohol interferes with attention to diet and medication due to impaired ability to make decisions53,58. This therefore, affects self-care related lifestyle behaviors including physical activity exercise as well as glucose self-monitoring. Other factors for example age of the patients (≥ 60 years), duration of treatment (< 5 years), having comorbidities, low family income, having informal education, and not having health insurance even though had increased risk for poor glycemic control, but they were not statistically significant.

The findings from this study have shown that, the problem of poor glycemic control among T2DM patients in Tanzania which is among developing countries is still a major health problem which needs collective majors and holistic approach among stakeholders in mitigating its adverse effects. Large multicenter epidemiologic studies in future may help to provide comprehensive and detailed explanations predictors and other related contributing factors.

Study limitations

The study had some limitations including the following: knowing the fact that our data involved patients only from a single health facility in the country, therefore, the findings cannot be generalized. The observed high prevalence of poor glycemic control in this study may be exaggeration of the actual true picture due the fact that data were collected from patients attending at a hospital, this might have resulted into selection bias. Our study cannot establish the causal-effect relationship due to the fact that it is cross-sectional. We could not collect information on drug prescription due to inconsistent documentation which we observed. Also, we could not involve use of HbA1c in determining glycemic control due to financial constraints.

Conclusion

This study reports a significant high prevalence of poor glycemic control among patients with T2DM. This is because for every ten patients, approximately seven of them had poor glycemic control. Alcohol intake and failure to adhere to regular follow-up among patients were the independent factors that were significantly associated with poor glycemic control. This shows that, positive modification of the lifestyle behaviors of patients with T2DM in Tanzania would help to improve glycemic control and prevent development of related complications.

Data availability

The dataset used for this study is restricted by the Research Ethical Committee of the institution detail due to containing sensitive patient information, however, it can be accessed upon reasonable request from the Directorate of Research Publication, and Consultancy (DRPC), University of Dodoma, P. O. Box 259, Dodoma, Tanzania. Email: drpc@udom.ac.tz.

Abbreviations

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- LMICs:

-

Low-and middle-income countries

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

References

American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 32, S262–S267 (2009).

Giri, B. et al. Chronic hyperglycemia mediated physiological alteration and metabolic distortion leads to organ dysfunction, infection, cancer progression and other pathophysiological consequences: An update on glucose toxicity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 107, 306–328 (2018).

Forbes, J. M. & Cooper, M. E. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol. Rev. 93, 137–188 (2013).

Abdul, M. et al. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes—Global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 10, 107–111 (2020).

Kotwas, A., Karakiewicz, B., Zabielska, P., Wieder-Huszla, S. & Jurczak, A. Epidemiological factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus: Evidence from the Global Burden of Disease. Arch. Public Health 79, 1–7 (2021).

Shaw, J. E., Sicree, R. A. & Zimmet, P. Z. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 87, 4–14 (2010).

Cho, N. et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 138, 271–281 (2018).

Hill-Briggs, F. et al. Social determinants of health and diabetes: A scientific review. Diabetes Care 44, 258–279 (2021).

Kazi, A. A. & Blonde, L. Classification of diabetes mellitus. Clin. Lab. Med. 21, 1–13 (2001).

Ramphal, R., Fauci, A. S., Braunwald, E. & Kasper, D. L. Endocrinology and Metabolism. Harrison Principles of Internal Medicine (McGraw Hill Medical, 2008).

US Department of Health and Human Services. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Natl. Diabetes Stat. Rep. 2 (2020).

Pastakia, S. D., Pekny, C. R., Manyara, S. M. & Fischer, L. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa—From policy to practice to progress: Targeting the existing gaps for future care for diabetes. Diabetes. Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 10, 247–263 (2017).

Mayega, R. W. & Rutebemberwa, E. Clinical presentation of newly diagnosed diabetes patients in a rural district hospital in Eastern Uganda. Afr. Health Sci. 18, 707–719 (2018).

Omar, S. M., Musa, I. R., ElSouli, A. & Adam, I. Prevalence, risk factors, and glycaemic control of type 2 diabetes mellitus in eastern Sudan: A community-based study. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042018819860071 (2019).

Leman, P. Validity of urinalysis and microscopy for detecting urinary tract infection in the emergency department. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 9, 141–147 (2002).

Kinimi, E., Balthazary, S., Kitua, S. & Msalika, S. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients seeking medical care at Morogoro regional referral hospital in Tanzania, Tanzan. J. Health Res. 19, 1–8 (2017).

Alemayehu, E., Id, G., Kassie, A. & Id, N. Glycemic control among diabetic patients in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta- analysis. PLoS One 14, e0221790 (2019).

Patrick, N. B., Yadesa, T. M., Muhindo, R. & Lutoti, S. Poor glycemic control and the contributing factors among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients attending outpatient diabetes clinic at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, Uganda. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 14, 3123–3130 (2021).

Kamuhambwa, A. R. & Charles, E. Predictors of poor glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients attending public hospitals in Dar es Salaam. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 6, 155–165 (2014).

Rwegerera, G. M. Adherence to anti-diabetic drugs among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania—A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 17, 252 (2014).

Demoz, G. T. et al. Predictors of poor glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes on follow-up care at a tertiary healthcare setting in Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 12, 1–7 (2019).

Ahmed, A. T., Karter, A. J., Warton, E. M., Doan, J. U. & Weisner, C. M. The relationship between alcohol consumption and glycemic control among patients with diabetes: The Kaiser Permanente Northern California diabetes registry. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 23, 275–282 (2008).

Duarte, F. G. et al. Sex differences and correlates of poor glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study in Brazil and Venezuela. BMJ Open 9, e023401 (2019).

Shamshirgaran, S. M. et al. Age differences in diabetes-related complications and glycemic control. BMC Endocr. Disord. 17, 1–7 (2017).

Ndumwa, H. P. iMedPub journals prevalence of substance use and associated factors among police officers, 1–11 (2021).

Mbatia, J., Jenkins, R., Singleton, N. & White, B. Prevalence of alcohol consumption and hazardous drinking, tobacco and drug use in urban Tanzania, and their associated risk factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 6, 1991–2006 (2009).

Kish, L. Statistical Design for Research (Wiley, 1987).

Westerterp, K. R. Physical activity and physical activity induced energy expenditure in humans: Measurement, determinants, and effects. Front. Physiol. 4, 90 (2013).

Agarwal, S. K. Cardiovascular benefits of exercise. Int. J. Gen. Med. 5, 541–545 (2012).

American Diabetes Association. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes. Diabetes Care 33, 1911 (2010).

Alhariri, A., Daud, F., Almaiman, A., Ayesh, S. & Saghir, M. Factors associated with adherence to diet and exercise among type 2 diabetes patients in Hodeidah city, Yemen. Life 7, 264–271 (2017).

Marathe, P. H., Gao, H. X. & Close, K. L. American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2017. Diabetes 9, 320–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-0407.12524 (2017).

Hoffmeister, M., Lyaruu, A. & Krawinkel, M. B. Assessment of nutritional intake, body mass index and glycemic control in patients with type-2 diabetes from Northern Tanzania. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 49, 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1159/000084179 (2005).

Camara, A. et al. Poor glycemic control in type 2 diabetes in the South of the Sahara: The issue of limited access to an HbA1c test. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 108, 187–192 (2015).

Sheleme, T., Mamo, G., Melaku, T. & Sahilu, T. Glycemic control and its predictors among adult diabetic patients attending Mettu Karl Referral Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia: A prospective observational study. Diabetes Ther. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-020-00861-7 (2020).

Temma, Y., Howteerakul, N., Suwannapong, N. & Rawdaree, P. Glycemic control and associated factors among elderly patients with type 2 diabetes in a tertiary hospital in Saku, Japan. Int. J. Gerontol. 15, 372–376 (2021).

Matsumura, S. et al. Development and pilot testing of quality indicators for primary care in Japan. JMA J. 2, 131–138 (2019).

Lang, V. B., Marković, B. B. & Vrdoljak, D. The association of lifestyle and stress with poor glycemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2: A Croatian nationwide primary care cross-sectional study. Croat. Med. J. 56, 357–365 (2015).

Urina-Jassir, M. et al. The effect of comorbidities on glycemic control among Colombian adults with diabetes mellitus: A longitudinal approach with real-world data. BMC Endocr. Disord. 21, 1–12 (2021).

Yeemard, F. et al. Prevalence and predictors of suboptimal glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in northern Thailand: A hospital-based cross-sectional control study. PLoS One 17, 50–59 (2022).

Timpel, P., Harst, L., Reifegerste, D., Weihrauch-Blüher, S. & Schwarz, P. E. H. What should governments be doing to prevent diabetes throughout the life course?. Diabetologia 62, 1842–1853 (2019).

Lubaki, J.-P.F., Omole, O. B. & Francis, J. M. Prevalence and factors associated with type 2 diabetes control in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 14, 134 (2022).

Lubaki, J. P. F., Omole, O. B. & Francis, J. M. Protocol: Developing a framework to improve glycaemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. PLoS One 17, 1–17 (2022).

FinaLubaki, J. P., Omole, O. B. & Francis, J. M. Glycaemic Control Among Type 2 Diabetes Patients in Sub-Saharan Africa from 2012 to 2022: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabetology and Metabolic Syndrome Vol. 14 (BioMed Central, 2022).

Bin Rakhis, S. A., AlDuwayhis, N. M., Aleid, N., AlBarrak, A. N. & Aloraini, A. A. Glycemic control for type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A systematic review. Cureus 14, 6–13 (2022).

Zhao, Q. et al. Follow-up frequency and clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: A prospective analysis based on multicenter real-world data. J. Diabetes 14, 306–314 (2022).

Asao, K., McEwen, L. N., Crosson, J. C., Waitzfelder, B. & Herman, W. H. Revisit frequency and its association with quality of care among diabetic patients: Translating Research into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD). J. Diabetes Complicat. 28, 811–818 (2014).

Yigazu, D. M. & Desse, T. A. Glycemic control and associated factors among type 2 diabetic patients at Shanan Gibe Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 10, 1–6 (2017).

Ramirez, L. D. H. et al. Factors influencing glycemic control in patients with diabetes type II in Mexican patients. J. Fam. Med. 3, 1051 (2016).

Ukai, T., Ichikawa, S., Sekimoto, M., Shikata, S. & Takemura, Y. Effectiveness of monthly and bimonthly follow-up of patients with well-controlled type 2 diabetes: A propensity score matched cohort study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 19, 1–9 (2019).

Al Mansari, A. et al. GOAL study: Clinical and non-clinical predictive factors for achieving glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes in real clinical practice. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 6, 1–10 (2018).

Abdissa, D. & Hirpa, D. Poor glycemic control and its associated factors among diabetes patients attending public hospitals in West Shewa Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia: An Institutional based cross-sectional study. Metab. Open 13, 100154 (2022).

Salama, M. S. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with alcohol consumption among persons with diabetes in Kampala, Uganda: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 21, 1–10 (2021).

Engler, P. A., Ramsey, S. E. & Smith, R. J. Alcohol use of diabetes patients: The need for assessment and intervention. Acta Diabetol. 50, 93–99 (2013).

Emanuele, N. V., Swade, T. F. & Emanuele, M. A. Consequences of alcohol use in diabetics. Alcohol Res. Health 22, 211–219 (1998).

Vos, T. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390, 1211–1259 (2017).

Kwok, A., Dordevic, A. L., Paton, G., Page, M. J. & Truby, H. Effect of alcohol consumption on food energy intake: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 121, 481–495 (2019).

Mostofsky, E., Mukamal, K. J., Giovannucci, E. L., Stampfer, M. J. & Rimm, E. B. Key findings on alcohol consumption and a variety of health outcomes from the nurses’ health study. Am. J. Public Health 106, 1586–1591 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J.Y., I.F.D. and E.D.M. designing, data correction, methodology and A.I.N. and D.B. statistical analysis, writing the first draft of the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yahaya, J.J., Doya, I.F., Morgan, E.D. et al. Poor glycemic control and associated factors among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 13, 9673 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36675-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36675-3

This article is cited by

-

Predictors of microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at regional referral hospitals in the central zone, Tanzania: a cross-sectional study

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Glycemic control and associated factors among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a cross-sectional study of Azar cohort population

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2023)

-

A case–control study to evaluate hematological indices in blood of diabetic and non-diabetic individuals in Ibb City, Yemen

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.