Abstract

Cognitive emotion regulation (CER) strategies are useful in evaluating the risk of developing emotional disorders and that they may define subjects’ styles. This study aims to explore the extent to which specific styles of CER strategies relate to the anxious and avoidant attachment dimensions in adults and whether such relationships operate similarly for women and men. Two hundred and fifteen adults (between 22 and 67 years old) completed the Spanish versions of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire and the Experiences in Close Relationships instrument. Cluster analysis, ANOVA and Student's t-test were used. Our results show that women and men can be successfully classified into two CER clusters (Protective and Vulnerable), distinguished by the higher use in the protective cluster of the CER strategies considered most adaptive and complex (Acceptance, Positive Refocusing, Refocus on Planning, Positive Reappraisal, and Putting into Perspective). However, only in women were the anxious and avoidant attachment dimensions significantly associated with CER style. In conclusion, from a clinical and interpersonal perspective, it is interesting to be able to predict the belonging to a Protective or Vulnerable coping style by analysing the CER strategies and to know their relationship with the adult affective system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emotion regulation refers to the set of competences that allow one to supervise, evaluate, and modify the processes that are implied in the origin of emotion, thereby modulating one’s emotional manifestations1. Due to its importance, emotion regulation has been addressed by different lines of research from a range of perspectives, including the biological, psychological, and socio-cultural. In this broad view, cognitive emotion regulation strategies are highlighted as a factor relevant to understanding our way of dealing with emotional threats. Garnefski et al.2 developed the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) to assess the thoughts most employed to handle challenging emotions or feelings, such as Self-Blame, Acceptance, Rumination, Positive Refocusing, Refocus on Planning, Positive Reappraisal, Putting into Perspective, Catastrophizing, and Blaming Others. Subsequent research has confirmed the presence of these nine primary strategies across different cultures and ages3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Research on cognitive emotion regulation strategies has revealed that, on the one hand, strategies usually referred to as “less adaptive” or “maladaptive,” such as Rumination, Catastrophizing, Self-Blame, and Blaming Others, are directly related to symptoms of depression and anxiety3,4,5,6. On the other hand, the so-called “adaptive strategies,” such as Positive Reappraisal, Putting into Perspective, and Acceptance, are inversely related to such symptoms (e.g.,7,8,9,10).

However, the functional relationship that defines maladaptive strategies as risk factors and adaptive strategies as prevention factors is not always applicable. It varies with such factors as the condition of the sample, e.g., clinical or community-dwelling, its age, and its cultural composition11,12,13. At the same time, various works have proposed that the adaptive or maladaptive nature of the strategies and, therefore, their protective or risk-enhancing function, also depends on various contextual factors14,15,16,17. The research available in this regard is still very scarce; so far, for example, the analysis has focused on contextual factors such as the controllability of the stressor18, the type or intensity of the emotion, and the social or achievement circumstances in which the strategies must be implemented19. In general, the results obtained describe a dynamic process in which contextual factors mediate the selection of whatever strategies may be the most effective in the specific circumstances that the person must face. These works, essentially, focus on the study of the cognitive and emotional effects associated with the regulation of the emotional response. However, most affective transactions take place in social settings. In fact, interpersonal processes (e.g., in a family, social, or couple setting) are a contextual factor that is especially relevant in terms of the emotions we experience and the way we regulate them20. Moreover, the research carried out from this interpersonal perspective is of relevance insofar as it provides information not only on the intrapsychic processes that underlie the regulation of emotion, but also on the effects of that regulation on different areas of a person’s life (e.g., health, affiliative tendencies, relationships, and conflict management)20,21. In relation to this, it seems evident that the styles of affective bonding that we deploy in interpersonal relationships could affect the processes that give rise to emotion and its regulation. The theory of attachment formulated by Bowlby22 looks at the bond of attachment from the perspective of how a baby–adult interaction system operates to keep the child close to the adult and to protect him or her from threats. According to this theory, as the child grows, the experiences of caring begin to be represented symbolically in an internal working model that gathers the essential aspects of the self and the other in an attachment relationship. However, as pointed out by Bretherton and Munholland23, in Bowlby’s theory22, internal working models should not be regarded as dispositions or temperament traits, since they are updated as the child develops. Numerous studies highlight the stability of an early attachment style during childhood and adolescence, especially the secure style24. The principles of attachment theory have been applied to adult relationships, revealing the presence of parallel styles of emotional relationships and threat coping. Nevertheless, correspondences between early attachment representations and romantic styles need to be addressed carefully. Measures of adult attachment, as the state of mind with respect to attachment, assessed by the AAI (Adult Attachment Interview) have shown a wide association with early attachment representations24. However, despite their conceptual analogies, mainstream research reports a weak relationship between the affective style in current romantic relationships and early attachment representations24,25. It has been speculated that the patterns of affective regulation observed in adult relations could be more strongly affected by current interpersonal exchanges. Therefore, the affective style displayed in adult relationships might be affected by factors that go beyond early attachment representations (such as previous experiences in romantic relationships, maturative changes, or significant life situations). Furthermore, previous research has proven that the adult affective style influences different areas of a person’s life, emerging as a relevant dimension for our understanding of adults’ cognitive emotion regulation styles. In general, anxiously attached adult individuals have been described as having a higher sensitivity for detecting threats and a bias towards a negative and exaggerated valuation of such threats. Alternatively, avoidantly attached adult individuals are defined by their attempts to render the system of attachment through methods such as emphasizing self-sufficiency, avoiding emotional closeness, denying their attachment needs, and maximizing their physical and emotional distance from others26,27. Predictably, insecure adult attachment dimensions have been related to symptoms of depression and anxiety or psychopathic traits28,29,30,31.

As far as we know, the relationship between an individual’s adult romantic style and their profile of cognitive emotion regulation remains unexplored, even when it is predictable that the two constructs may be interrelated. To fill this gap, in this work we explore the relationship between adult cognitive emotion regulation style and the avoidant and anxious adult attachment dimensions in the context of a romantic relationship, examining whether such a connection works in a similar way for men and women. We hope that this work will improve our knowledge about the cognitive style of emotional regulation in women and men and about how these styles relate to the affective bonds that both maintain with their partners.

Method

Participants

A total of 215 people participated in the study, ranging in age from 22 to 67 years old (M = 41.03 years old, SD = 10.49). Of the participants, 30.2% were men (M = 42.20 years old, SD = 10.29), while 69.8% were women (M = 40.53 years old, SD = 10.61). Regarding academic level, most of the sample held a university degree (87%), and the rest of the participants had professional training (6.5%) or had graduated from secondary school (4.7%) or primary school (1.9%). Employment status was also taken into consideration: 48.4% had a permanent job, 14% had a temporary job, 2.3% were retired, and the rest of the participants either did not work (13.5%) or were focusing exclusively on their studies (21.9%). Participation in this research was voluntary, and there were no economic or academic rewards.

Instruments

The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire2, Spanish version (CERQ-S)32 consists of 36 items, four for each of the nine cognitive emotion regulation strategies it measures: Self-Blame (i.e., thinking that one is responsible for what happened), Acceptance (i.e., accepting what has happened and resigning oneself to it), Rumination (i.e., reflecting on one’s feelings and thoughts associated with what happened), Positive Refocusing (i.e., thinking about enjoyable experiences instead of about the stressful event), Refocus on Planning (i.e., concentrating on the measures to adopt in response to the event), Positive Reappraisal (i.e., considering the positive aspects of what happened), Putting into Perspective (i.e., reducing the relevance of the event), Catastrophizing (i.e., having thoughts that intensify the negative side of what happened), and Blaming Others (i.e., having thoughts that shift the blame for what happened onto others). In turn, these nine scales can be grouped into two more general categories, namely adaptive or appropriate strategies (Acceptance, Positive Refocusing, Refocus on Planning, Positive Reappraisal, and Putting into Perspective) and maladaptive or inappropriate strategies (Self-Blame, Rumination, Catastrophizing, and Blaming Others)2,32,33. These two categories (more adaptive strategies and less adaptive strategies) will be the ones used in this research and are the result of the sum of the corresponding CERQ first-order dimensions. The CERQ has good psychometric properties, both in its original version2 and in the versions adapted to other languages, in which the structure of the original nine-factor model has been confirmed6,32,33,34,35. In the sample used in the original study2,36, the internal consistency (alpha) of the scales ranged from 0.75 (Self-Blame) to 0.86 (Refocus on Planning). In our study the alpha values ranged from 0.70 (Acceptance) to 0.89 (Positive Reappraisal), with coefficient alphas of 0.89 and 0.82 for the more and less adaptive strategies, respectively.

Experiences in Close Relationships37 Spanish version (ECR-S)38 is a 32-item instrument containing a 7-point (1 = “strongly disagree” and 7 = “strongly agree”) Likert-type answer scale that has been validated within the adult Spanish population. It enables the evaluation of the original ECR’s orthogonal romantic attachment dimensions of anxiety and avoidance. In the ECR-S, 17 items measure anxiety about relationships (for instance, “I resent it when my partner spends time away from me”) and 15 items measure avoidance of intimacy (e.g., “I am nervous when partners get too close to me”). The items appear in the same order as in the English-language ECR. The ECR has good psychometric properties, both in its original version37 and in the Spanish version38. According to its authors, the ECR-S presents indexes of satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.87 for the Avoidance dimension and 0.85 for the Anxiety dimension. In our study, the alpha values ranged from 0.92 for Avoidance to 0.88 for Anxiety.

Procedure

This cross-sectional, relational, and descriptive research study was carried out between January 2020 and December 2022. The sample was obtained through a form that was uploaded on an institutional open web page of the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED; https://www.uned.es). They were informed that their participation, which was voluntary and anonymous, would comprise completing a series of sociodemographic data and two questionnaires (CERQ-S and ECR-S). All participants signed the informed consent through the Internet form (by checking the corresponding checkbox). This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (protocol number 25-PSI-2022) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association)39.

Not being 18 years of age at the time of the study and not having signed the informed consent were considered exclusion criteria for the study.

Although the total sample consisted of 215 participants, five cases were eliminated from the analyses because three participants did not indicate their gender and two left unanswered more than four of the instrument’s items measuring attachment. In the remaining cases, missing values for an item were replaced by the mean value of the item. The missing values, distributed randomly among the different items from these scales, represent 0.32% of the data from the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire and 0.36% from the Experiences in Close Relationships instrument.

Data analysis

The statistical analyses employed were as follows: Descriptive analysis and Pearson's correlations between the first and second order dimensions of the CERQ and the attachment dimensions (avoidance and anxiety). Cluster analysis (K-means) was used to obtain groups of subjects who were similar in their cognitive emotion regulation style (in all cases, the criterion of K = 2 was used, which is the minimum value that allows capturing differences between participants). This analysis was used for the total sample and later also separately for the all-male and all-female subsamples. The clustering process used the scores from the subjects in the second-order factor dimensions of the CERQ-S and used One-Way ANOVA to examine the relevance of the variables in the process of conglomeration. Student’s t-test and Hedges’ g (95% interval confidence) were used to analyse the possible statistical differences and the effect size (ES) between the two coping styles identified in each case (total sample and separate sub-samples of men and women) in the nine first-order dimensions of the CERQ-S and in the two dimensions of adult attachment. IBM SPSS 27 was used for the statistical analysis.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Descriptive analysis and correlation matrix were calculated between the first and second-order dimensions of the CERQ and avoidance and anxiety attachment dimensions (Table 1).

Cluster analysis according to cognitive emotional coping type

To construct the clusters, the participants’ scores on the second-order factors on the CERQ (More vs. Less adaptive strategies) were employed as variables. Two groups were obtained (Table 2 shows the results of the clusterization process and the centres of the final clusters). The first cluster consisted of 124 participants, who were grouped together according to their ability to use a higher amount of the more adaptive cognitive emotional coping strategies (CECS): Acceptance, Positive Refocusing, Refocus on Planning, Positive Reappraisal, and Putting into Perspective (Protective style). The second cluster consisted of 91 participants, who were grouped together based on their minor tendency to use the more adaptive CECS, resulting in a more equitable use of the more and the less adaptive cognitive emotional regulation strategies (Vulnerable style). In both groups, the use of the less adaptive strategies was similar (Fig. 1). In summary, in one group the use of adaptive strategies is clearly higher than that of non-adaptive ones (protective group); while in another group, clearly differentiated, the use of adaptive strategies is simply superior to that of non-adaptive strategies (vulnerable group).

Subsequently, the two groups were compared in the nine first-order dimensions of the CERQ-S. Significant statistical differences were found in five of the nine dimensions of the CERQ-S considered more adaptive. The participants from group 1 (Protective style) scored significantly higher than the participants from group 2 (Vulnerable style) in the dimensions of Positive Refocusing, Refocus on Planning, Positive Reappraisal, Putting into Perspective (large ES), and Acceptance (medium ES). In contrast, no statistically significant differences were found between the two groups in the use of Self-Blame, Rumination, Catastrophizing, or Blaming Others. The results indicate that the most relevant strategies for differentiating between both coping styles are those described above as the “more adaptive” strategies (see Table 3).

Analysis of attachment factors according to coping style

Once the two types of participants were identified according to their CECS style, their mean scores on the two dimensions of adult attachment evaluated via the ERC-S were compared. Statistically significant differences were found in both dimensions of attachment (Table 3). The participants from the protective style, characterized by the more frequent use of the more adaptive CECS, were shown to have lower scores on avoidance (small ES) and anxiety (medium ES) attachment dimensions.

Cluster analysis according to cognitive emotional coping type by gender

The cluster analysis was repeated separately for the all-male and all-female samples. As in the previous case, two participants groups were obtained. Table 4 shows the results of the clusterization process and the centres of the final clusters for men and women. As in the previous analysis, the differences between the clusters are determined by the group of more adaptive strategies. In both samples, the people included in the first group (Protective style) are characterized by a higher score on the more adaptive CECS. In contrast, the use of the less adaptive strategies is similar for the four groups.

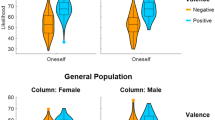

The first group (Protective style) consisted of 24 men and 87 women, who were grouped together according to their ability to use a higher amount of the more adaptive CECS (Acceptance, Positive Refocusing, Refocus on Planning, Positive Reappraisal, and Putting into Perspective). The second group (Vulnerable) consisted of 39 men and 60 women. As can be seen in Fig. 2 (and similarly to Fig. 1), if a cut-off point were to be established to differentiate between both groups, it would be at around 70 points in the more adaptive strategies.

In comparing mean CECS scores according to group (Protective vs. Vulnerable), very similar results were obtained for men and women (see Table 5). Significant statistical differences were found in the five first-order dimensions of the CERQ-S considered to be more adaptive strategies. Specifically, the participants (men or women) from group 1 (Protective style) scored significantly higher than the participants from group 2 (Vulnerable style) in the dimensions of Acceptance, Positive Refocusing, Refocus on Planning, Positive Reappraisal, and Putting into Perspective, with large effect sizes, except for the group of women in the Acceptance dimension (medium ES). Regarding the strategies considered less adaptive, no statistically significant differences in Self-Blame or Rumination were found in either of the two groups. In contrast, different results were obtained in the group of men and women in the dimensions of Catastrophizing and Blaming Others. Specifically, on the one hand, women fitting group 2 (Vulnerable style) scored significantly higher than those aligning with group 1 (Protective style) on Catastrophizing (small ES); however, no statistically significant differences were found in men. On the other hand, the men from group 1 (Protective style) scored significantly higher than those from group 2 (Vulnerable style) on the strategy of Blaming Others (medium ES), in contrast to the women, among whom no statistically significant differences were found between the two styles.

Analysis of attachment factors according to coping style by gender

This analysis was carried out on men and women separately. The two groups yielded different results in the attachment dimensions (see Table 5). In the group of men, no differences were found between the two cognitive emotional regulation styles in the Anxious and Avoidant attachment dimensions. In contrast, the women belonging to group 2 (Vulnerable style) scored significantly higher than those aligning with group 1 (Protective style) in the Avoidant (small ES) and Anxious (medium ES) attachment dimensions.

Discussion

Cognitive strategies for emotional self-regulation play an important role in the way we deal with emotions and are of great relevance in clinical settings. Such strategies as Rumination or Catastrophizing are usually related to depression or anxiety symptoms3,4,5,10, while other strategies considered as “adaptive,” such as Positive Refocusing or Putting into Perspective, are inversely related to those same symptoms7,8,9,10,14,40,41,42. For this reason, results like those mentioned above have promoted the consideration of “multivariate patterns” of cognitive regulation strategies as an alternative to targeting isolated strategies of cognitive regulation43. Accordingly, our study approach focused not on isolated strategies, nor even on groupings of strategies, but on individual styles of the use of strategies, which emerges as an adequate method to produce a realistic image of how individuals use cognitive strategies for regulation.

The results of our work identified two cognitive styles of cognitive emotion regulation. Specifically, individuals with a noteworthy tendency to use the cognitive strategies usually related to higher mental health scores (Acceptance, Positive Refocusing, Refocus on Planning, Positive Reappraisal, and Putting into Perspective) fit a Protective style, which runs counter to a second, Vulnerable style composed primarily of individuals who make a significantly less noteworthy use of these same strategies. The statistical analyses also reveal that the use of the so-called adaptive strategies (Acceptance, Positive Refocusing, Refocus on Planning, Positive Reappraisal, and Putting into Perspective) is significant enough to distinguish individuals in terms of their style (see Fig. 1), suggesting that these cognitive emotion regulation strategies may be crucial for individuals to preserve psychological adjustment and avoid the risk of developing emotional disorders such as depression or anxiety. In terms of clinical implications, this result suggests the desirability of involving people in the use of "adaptive" and complex strategies, since these strategies are revealed as the discriminating factor between the two regulation styles observed. Interestingly, the current research agrees on highlighting the complexity and singularity of adaptive strategies, suggesting that Positive Reappraisal, Positive Refocusing, and Putting into Perspective may demand higher levels of attentional control abilities, which in turn implies that cognitive control deficits in working memory, interference control, or perseveration could lead to greater reliance on the cognitive strategies of Self-Blame, Acceptance, Rumination, and Catastrophizing3,44,45, which require less cognitive elaboration.

Traditionally, differences have been observed between men and women with respect to the greater use of one or another emotional regulation strategy46,47, noting, among other generalized effects, a greater presence of rumination or internalized coping styles in women48. These results are consistent with the significantly higher risk among women of developing a depression or anxiety disorder46,49,50.

Nevertheless, other research emphasizes that the nine cognitive emotional regulation strategies measured by the CERQ are gender-invariant, although women are more likely than men to use adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies51. In addition to these heterogenous results, some authors have pointed out that the relationship between the use of emotional regulation strategies and emotional disorders might not be the same for men and women52,53. In this puzzle of diverse results, in which not only cognitive or neurological but also cultural aspects have an influence, we find that from the point of view of the subjects, there are no differences in the cognitive regulation styles of men and women. In our study, male and female subjects showed the same two cognitive regulation styles, differentiated by the greater use of the most adaptive strategies. In addition, while the Vulnerable style described most of the men, in women the Protective style predominated – a result that is consistent with the evidence indicating that women tend to score higher in emotional intelligence54,55,56 and interpersonal competence57,58,59.

Although the cognitive coping groups showed identical clustering in men and women, a remarkable gender difference emerged. Specifically, men who fit the Protective style were significantly more likely to blame others than men allocated to the Vulnerable style (see Table 5). This issue, located in the cognitive coping groups of men, contrasts with the evidence that places this strategy among the least adaptive and relates it to the presence of psychopathy traits51,60,61,62,63, pointing again to the consideration already raised that the degree to which a regulatory strategy is adaptive depends not only on its nature but also on its flexible use and effective implementation by the individual14,15,16,17. Thus, while the rigid use of the Blaming Others strategy could generate maladaptive consequences for the individual, our study suggests that, in the broader context of a healthy and complex style of cognitive regulation, the use of this strategy could be “protective” for the user. Blaming Others is a strategy that involves externalizing responsibility, thus helping to avoid the emergence of negative emotions (e.g., guilt or shame)64 and to preserve the positive self-concept that the person has of himself65,66. In addition, Blaming Others is the strategy most linked to interpersonal relationships, as some authors have already pointed out60. This uniqueness puts us on the track of considering gender differences from the point of view of “the Other”. Recourse to Blaming Others might be more available to those people who have less of a tendency to put themselves in the shoes of the other, that is, to feel empathy. Empathy is a complex emotion that involves being able to share another person’s emotional state and mental perspective. This emotion traditionally shows higher levels in women, particularly in studies based on self-reported measures67,68,69. In turn, impassivity, a contrast factor to empathy defined as a lack of solidarity with and sensitivity to others, is a key factor in the research on gender differences70. Thus, although we cannot explain the reasons for the observed difference in the use of Blaming Others on the part of the men who fit the Protective style, based on previous research, we can hypothesize that a higher sensitivity to the perspectives of others and their feelings, usually found in women, may be underlying this gender singularity, which allows men to have one more strategy in their adaptive style of cognitive emotion regulation.

Gender differences were also found in the relationship between cognitive coping styles and adult attachment dimensions. As can be seen in Table 5, attachment dimensions were significantly related to the cognitive emotion regulation clusters of women, but they were not significant for men. Specifically, women who showed anxious or avoidant attachment in their relationships were more likely to be included in the Vulnerable cognitive emotion regulation group. That is, interpersonal attachment emerged as a more relevant factor in the cognitive emotional regulation processes of women than in those of men. The motives for this connection remain unclear, but we can hypothesize that this difference may be reinforced by the influence of cultural gender stereotypes. Parents socialize their sons and daughters according to culturally prescribed gender roles, which helps to explain why, as children become more aware of their images, sex role stereotypes, and expectations, these differences increase71. In most cultures, women, more than men, are required to attend to the perspectives of others and to take care of others’ interests and desires, which may help to explain the higher interrelation, observed in our study, between their interpersonal attachment insecurities and their cognitive emotion regulation style. In this sense, interpersonal attachment style could be acting in women as a source of additional affective information that, together with the rest of their emotional resources, contributes to the selection of a specific regulatory style16,72. This normalized dynamic could be altered in insecure attachment styles; in people with these attachment styles, the associated cognitive biases (e.g., cognitive and emotional distancing in avoidant attachment, or negative evaluation and high emotional reactivity in anxious attachment) would act as a contextual factor, favouring the selection of a higher-risk emotional regulation style, i.e., the Vulnerable style.

In sum, our research confirms that women and men display similar cognitive emotion regulation styles and that cognitive strategies considered more adaptive (Acceptance, Positive Refocusing, Refocus on Planning, Positive Reappraisal, and Putting into Perspective) play a decisive role that predicts their belonging to one or another cognitive emotion regulation style. In turn, although our work does not provide an explanation for some of the observed gender differences, it does highlight some interesting points that may improve our understanding of them. First, although the styles of cognitive emotion regulation were similar in women and men, men apparently presented a wider range of adaptive strategies by including “Blaming Others” in the Protective style of cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Second, the cognitive emotion regulation styles of men were more independent of their interpersonal affective system than was the case in women, which may be related to the gender differences observed in the socio-cognitive development of women and men in most cultures. The observed gender differences highlight the style of bonding, with the couple as a factor of special relevance in the dynamics of the emotional regulation of women. In this sense, our results suggest the relevance of considering the extent to which toxic and abusive romantic relationships may affect the individual’s cognitive way of dealing with threats or challenges.

Data availability

The data of the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation: Past, present, future. Cogn. Emot. 13, 551–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999399379186 (1999).

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V. & Spinhoven, P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personal. Individ. Differ. 30, 1311–1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00113-6 (2001).

Domaradzka, E. & Fajkowska, M. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies in anxiety and depression understood as types of personality. Front. Psychol. 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00856 (2018).

Garnefski, N. & Kraaij, V. Specificity of relations between adolescents’ cognitive emotion regulation strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Cogn. Emot. 32, 1401–1408. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1232698 (2018).

Holgado-Tello, F. P., Amor, P. J., Lasa-Aristu, A., Domínguez-Sánchez, F. J. & Delgado, B. Two new brief versions of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire and its relationships with depression and anxiety. An. Psicol. 34, 458–464. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.34.3.306531 (2018).

Martin, R. C. & Dahlen, E. R. Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression, anxiety, stress, and anger. Personal. Individ. Differ. 39, 1249–1260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.06.004 (2005).

Balzarotti, S., Biassoni, F., Villani, D., Prunas, A. & Velotti, P. Individual differences in cognitive emotion regulation: Implications for subjective and psychological well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 17, 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9587-3 (2016).

Doron, J., Thomas-Ollivier, V., Vachon, H. & Fortes-Bourbousson, M. Relationships between cognitive coping, self-esteem, anxiety and depression: A cluster-analysis approach. Personal. Individ. Differ. 55, 515–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.017 (2013).

Lasa-Aristu, A., Delgado, B., Holgado-Tello, F. P., Amor, P. J. & Domínguez-Sánchez, F. J. Profiles of cognitive emotion regulation and their association with emotional traits. Clínica Salud 30, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2019a6 (2019).

Stikkelbroek, Y., Bodden, D. H. M., Kleinjan, M., Reijnders, M. & van Baar, A. L. Adolescent depression and negative life events, the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation. PLOS ONE 11, e0161062. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161062 (2016).

Garnefski, N. & Kraaij, V. Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Personal. Individ. Differ. 40, 1659–1669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.009 (2006).

Potthoff, S. et al. Cognitive emotion regulation and psychopathology across cultures: A comparison between six European countries. Personal. Individ. Differ. 98, 218–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.022 (2016).

Zhuang, X. Y. et al. The differential functions of cognitive emotion regulation strategies in Chinese adolescents with different levels of anxiety problems in Hong Kong. J. Child Fam. Stud. 29, 3433–3446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01825-y (2020).

Aldao, A. The future of emotion regulation research: Capturing context. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 8, 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612459518 (2013).

Bonanno, G. A. & Burton, C. L. Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 8, 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613504116 (2013).

Burton, C. L. & Bonanno, G. A. Regulatory flexibility and its role in adaptation to aversive events throughout the lifespan in Emotion, aging, and health (eds. Ong, D. & Löckenhoff, C. E.) 71–94 (American Psychological Association, 2016).

Sheppes, G. Transcending the “good & bad” and “here & now” in emotion regulation: Costs and benefits of strategies across regulatory stages in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (ed. Gawronski, B.) 185–236 (Academic Press, 2020).

Troy, A. S., Shallcross, A. J. & Mauss, I. B. A person-by-situation approach to emotion regulation: Cognitive reappraisal can either help or hurt, depending on the context. Psychol. Sci. 24, 2505–2514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613496434 (2013).

Aldao, A. & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. The influence of context on the implementation of adaptive emotion regulation strategies. Behav. Res. Ther. 50, 493–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.04.004 (2012).

Lindsey, E. W. Relationship context and emotion regulation across the life span. Emotion 20, 59–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000666 (2020).

English, T. & Eldesouky, L. We’re not alone: Understanding the social consequences of intrinsic emotion regulation. Emotion 20, 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000661 (2020).

Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment, 2nd ed. (New York Basic Books, 1982)

Bretherton, I. & Munholland, K. A. Internal working models in attachment relationships: Elaborating a central construct in attachment theory in Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications, 2nd ed. (eds. Cassidy, J. & Shaver, P. R.) 102–127 (The Guilford Press, 2008).

Belsky, J. Developmental origins of attachment styles. Attach. Hum. Dev. 4, 166–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730210157510 (2002).

Bouthillier, D., Julien, D., Dubé, M., Bélanger, I. & Hamelin, M. Predictive validity of adult attachment measures in relation to emotion regulation behaviors in marital interactions. J. Adult Dev. 9, 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1020291011587 (2002).

Cassidy, J. & Kobak, R. R. Avoidance and its relation to other defensive processes in Clinical implications of attachment. (eds. Belsky, J. & Nezworski, T.) 300–323 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, 1988).

Mikulincer, M. & Shaver, P. R. Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. (The Guilford Press, 2007).

Dobson, O., Price, E. L. & DiTommaso, E. Recollected caregiver sensitivity and adult attachment interact to predict mental health and coping. Personal. Individ. Differ. 187, 111398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111398 (2022).

Jinyao, Y. et al. Insecure attachment as a predictor of depressive and anxious symptomology. Depress. Anxiety 29, 789–796. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21953 (2012).

Kyranides, M. N., Kokkinou, A., Imran, S. & Cetin, M. Adult attachment and psychopathic traits: Investigating the role of gender, maternal and paternal factors. Curr. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01827-z (2021)

Zheng, L., Luo, Y. & Chen, X. Different effects of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 37, 3028–3050. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407520946482 (2020).

Domínguez-Sánchez, F. J., Lasa-Aristu, A., Amor, P. J. & Holgado-Tello, F. P. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. Assessment 20, 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191110397274 (2013).

Jermann, F., Van der Linden, M., d’Acremont, M. & Zermatten, A. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire (CERQ). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 22, 126–131. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.22.2.126 (2006).

Abdi, S., Taban, S. & Ghaemian, A. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire: Validity and reliability of Persian translation of CERQ-36 item. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 32, 2–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.001 (2012).

Cakmak, A. & Cevik, E. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire: Development of Turkish version of 18-item short form. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 4, 2097–2102 (2010).

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & Spinhoven, Ph. Manual for the use of Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. (Leiderdorp, The Netherlands, 2002).

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L. & Shaver, P. R. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview in Attachment theory and close relationships (eds. Simpson, J. A. & Rholes, W. S.) 46–76 (The Guilford Press, 1998).

Alonso-Arbiol, I., Balluerka, N. & Shaver, P. R. A Spanish version of the experiences in close relationships (ECR) adult attachment questionnaire. Pers. Relatsh. 14, 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2006.00141.x (2007).

WMA - The World Medical Association-WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V. & van Etten, M. Specificity of relations between adolescents’ cognitive emotion regulation strategies and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. J. Adolesc. 28, 619–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.12.009 (2005).

Legerstee, J. S., Garnefski, N., Jellesma, F. C., Verhulst, F. C. & Utens, E. M. W. J. Cognitive coping and childhood anxiety disorders. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 19, 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-009-0051-6 (2010).

Legerstee, J. S., Garnefski, N., Verhulst, F. C. & Utens, E. M. W. J. Cognitive coping in anxiety-disordered adolescents. J. Adolesc. 34, 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.04.008 (2011).

Garnefski, N. & Kraaij, V. Cognitive coping and psychological adjustment in different types of stressful life events. Individ. Differ. Res. 7, 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.009 (2009).

Abdollahpour Ranjbar, H. et al. Investigating cognitive control and cognitive emotion regulation in Iranian depressed women with suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Suicide Life. Threat. Behav. 51, 586–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12735 (2021).

Mohammed, A.-R., Kosonogov, V. & Lyusin, D. Is emotion regulation impacted by executive functions? An experimental study. Scand. J. Psychol. 63, 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12804 (2022).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 8, 161–187. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109 (2012).

Tamres, L. K., Janicki, D. & Helgeson, V. S. Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc. 6, 2–30. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0601_1 (2002).

Johnson, D. P. & Whisman, M. A. Gender differences in rumination: A meta-analysis. Personal. Individ. Differ. 55, 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.019 (2013).

Altemus, M., Sarvaiya, N. & Neill Epperson, C. Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 35, 320–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.05.004 (2014).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Larson, J. & Grayson, C. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77, 1061–1072. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1061 (1999).

Wang, J. et al. Factorial invariance of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire across gender in Chinese college students. Curr. Psychol. 1, 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02291-5 (2021).

Duarte, A. C., Matos, A. P. & Marqués, C. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: Gender’s moderating effect. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 165, 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.632 (2015).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. & Aldao, A. Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Personal. Individ. Differ. 51, 704–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.012 (2011).

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., Shiffman, S., Lerner, N. & Salovey, P. Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: A comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91, 780–795. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.780 (2006).

Mirgain, S. A. & Cordova, J. V. Emotion skills and marital health: The association between observed and self–reported emotion skills, intimacy, and marital satisfaction. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 26, 983–1009. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2007.26.9.983 (2007).

Rooy, D. L. V., Dilchert, S., Vlswesvaran, C. & Ones, D. S. Multiplying intelligences: Are general, emotional, and practical intelligences equal? in A critique of emotional intelligence: What are the problems and how can they be fixed? (ed. Murphy, K. R.) 235–262 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2006).

Barrett, L. F., Lane, R. D., Sechrest, L. & Schwartz, G. E. Sex differences in emotional awareness. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 26, 1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672002611001 (2000).

Ciarrochi, J., Hynes, K. & Crittenden, N. Can men do better if they try harder: Sex and motivational effects on emotional awareness. Cogn. Emot. 19, 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930441000102 (2005).

Hall, J. A. & Schmid Mast, M. Are women always more interpersonally sensitive than men? Impact of goals and content domain. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 34, 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207309192 (2008).

Kyranides, M. N. & Neofytou, L. Primary and secondary psychopathic traits: The role of attachment and cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Personal. Individ. Differ. 182, 111106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111106 (2021).

Sharma-Patel, K. et al. Patterns in blame attributions in maltreated youth: Association with psychopathology and interpersonal functioning. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 23, 567–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2014.920456 (2014).

Trickey, D., Siddaway, A. P., Meiser-Stedman, R., Serpell, L. & Field, A. P. A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32, 122–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.001 (2012).

Zlomke, K. R. & Hahn, K. S. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies: Gender differences and associations to worry. Personal. Individ. Differ. 48, 408–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.11.007 (2010).

Tangney, J. P. & Dearing, R. L. Shame and guilt. xvi, 272 (Guilford Press, 2002). https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412950664.n388.

Green, S., Moll, J., Deakin, J. F. W., Hulleman, J. & Zahn, R. Proneness to decreased negative emotions in major depressive disorder when blaming others rather than oneself. Psychopathology 46, 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1159/000338632 (2013).

Tracy, J. L. & Robins, R. W. Appraisal antecedents of shame and guilt: Support for a theoretical model. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 32, 1339–1351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206290212 (2006).

Baez, S. et al. Men, women…who cares? A population-based study on sex differences and gender roles in empathy and moral cognition. PLOS ONE 12, e0179336 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179336 (2017).

Carrasco, M. Á., Delgado, B., Barbero, M. I., Holgado-Tello, F. P. & Del Barrio, M. V. Propiedades psicométricas del interpersonal reactivity index (IRI) en población infantil y adolescente española. Psicothema 23, 824–831 (2011).

Mestre, M. V., Samper, P., Frías, M. D. & Tur, A. M. Are women more empathetic than men? A longitudinal study in adolescence. Span. J. Psychol. 12, 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1138741600001499 (2009).

Holgado-Tello, F. P., Delgado, B., Carrasco, M. A. & Del Barrio, M. V. Interpersonal reactivity index: Analysis of invariance and gender differences in Spanish youths. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 44, 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0327-9 (2013).

Eisenberg, N. Empathy and sympathy. In Handbook of emotions (eds. Lewis, M. & Haviland-Jones, J.) 473–485 (The Guilford Press, 2004)

Blanke, E. S. et al. Mix it to fix it: Emotion regulation variability in daily life. Emotion 20, 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000566 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the design, performed the study, and reviewed the final version manuscript. B.D. and F.J.D.-S. wrote the introduction and discussion. P.J.A. and F.P.H.-T. performed the statistical analyses and wrote the results, tables and figures.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Delgado, B., Amor, P.J., Domínguez-Sánchez, F.J. et al. Relationship between adult attachment and cognitive emotional regulation style in women and men. Sci Rep 13, 8144 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35250-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35250-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.