Abstract

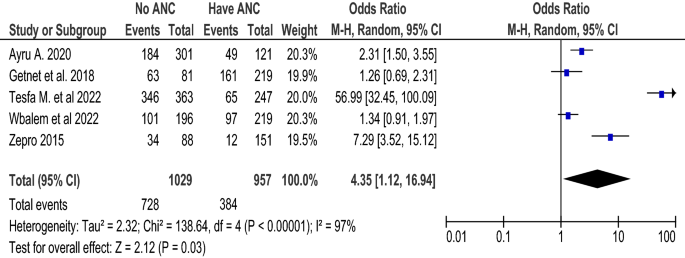

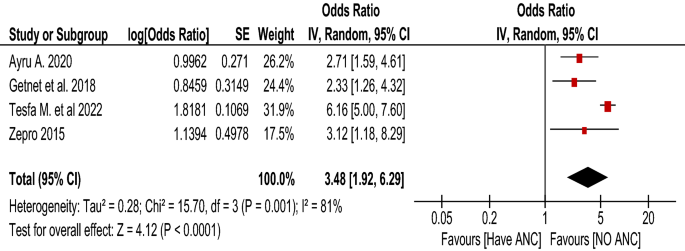

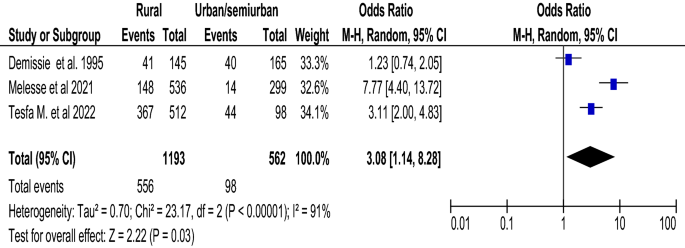

Food taboos have a negative impact on pregnant women and their fetuses by preventing them from consuming vital foods. Previous research found that pregnant women avoided certain foods during their pregnancy for a variety of reasons. This review aimed to determine the pooled prevalence of food taboo practices and associated factors in Ethiopia. In compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline, we searched the literature using PubMed/MEDLINE, AJOL (African Journal Online), HINARI, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Google electronic databases. The random-effects model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of food taboo and its determinants at a 95% confidence interval with their respective odds ratios. The pooled food taboo practice among Ethiopian pregnant women was 34.22% (95% CI 25.47–42.96), and after adjustment for publication bias with the trim-and-fill analysis, the pooled food taboo practice of pregnant women was changed to 21.31% (95% CI: 10.85–31.67%). Having less than a secondary education level (OR = 3.57; 95% CI 1.43–8.89), having no ANC follow-up (OR = 4.35; 95% CI 1.12–16.94), and being a rural resident (OR = 3.08; 95% CI 1.14–8.28) were the significant factors. Dairy products, some fruits, green leafy vegetables, meat, and honey are among the taboo foods. The most frequently stated reasons for this taboo practice were: fear of producing a big fetus, which is difficult during delivery; attachment to the fetus's body or head; and fear of fetal abnormality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the course of pregnancy, physiological changes like new tissue development and synthesis, mother tissue growth, and the growing fetus significantly increase energy and food needs1. To fulfill this increased demand, pregnant women must consume an adequate and balanced diet that includes a sufficient number of macronutrients and micronutrients2. Pregnant women restrict themselves from specific foods for several reasons. Pregnant women avoid foods because of a strong dislike (aversion) caused by pregnancy; others avoid them due to medical grounds. However, a high proportion of pregnant women avoid specific foods due to cultural beliefs or impositions in developing countries like Ethiopia3,4. Food taboos vary by culture, society, and even among pregnant women, especially in rural areas, and are typically passed down from generation to generation5,6.

Although the consumption of important, diversified foods is essential to producing the hormones needed during pregnancy, food taboos during pregnancy are a common practice, particularly in developing countries7,8. Prenatal dietary taboo influence what they eat, leaving them vulnerable to micronutrient deficits, including vitamin A, folate, iodine, iron, calcium, and zinc, which are all important during pregnancy. Previous studies from Nigeria9,10, Gambia11, Kenya12, and Ethiopia13,14,15 show that pregnant women are typically prohibited from eating foods high in iron, carbohydrates, animal products, and micronutrients. Avoiding most vital food groups leaves these pregnant women with limited dietary diversity and vulnerable to many nutrient deficiencies, including micronutrient deficiencies, which can lead to pregnancy malnutrition9,11. Worldwide, about 9.8 million women are deficient in vitamin A16, and iron deficiency, contributes to at least 18% of maternal mortality in developing countries16,17. In sub-Saharan Africa, women are particularly exposed to inadequate intake of micronutrients, resulting in different types of malnutrition, which can occur even in the presence of adequate energy and protein intake due to food restrictions during pregnancy7,18.

A number of researchers have reported the prevalence of food taboo practices in Ethiopia15,19,20,21. The study done in Addis Ababa shows 18% of pregnant women avoid one or more food items due to food taboos19. Previous studies identified age, parity, support from husbands and communities, knowledge, dietary counseling, attendance at antenatal care (ANC), educational status, and cultural beliefs as major determinants22. Individual studies on the prevalence of food taboo practice and associated factors in Ethiopia show varying and inconsistent findings. Previous studies conducted on pregnant women's food taboo practices provided a qualitative discussion on the most commonly avoided foods and their reasons, but they didn’t provide pooled food taboo practices among pregnant women in Ethiopia and associated factors using statistical analysis23. This systematic review and meta-analysis included the most recent primary studies available, which can provide a recent summarized magnitude of food taboo practices and factors influencing them. By reviewing 16 articles that mentioned food taboos during pregnancy as well as the reasons for the food prohibition, this review may help to fill a gap in summarized information on the prevalence of food taboo practices during pregnancy. The findings of this study can help policymakers, planners, and health service providers by generating and disseminating evidence-based information that can aid in the design and implementation of appropriate interventions. Our study paves the way for future investigations on the determinants of changes and levels of food taboo practices during pregnancy. Hence, the goal of this systematic review and meta-analysis study is to determine the pooled prevalence of food taboos and associated factors among pregnant women in Ethiopia.

Methods and materials

Study design and search strategy

We systematically reviewed and analyzed available research articles to determine the pooled prevalence of food taboo practices and associated factors among pregnant women in Ethiopia. The review protocol and reporting were done using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol (PRISMA-P) and the Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies guideline. The review protocol was filed with the International Registration of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the registration number CRD42022304915 on February 20, 2022, in order to reduce duplication of reviews and increase transparency in the review process. The study question's core topics were used to develop a search strategy that included food taboo, pregnant women, prevalence, factors, and Ethiopia. For each key concept, appropriate free-text words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were developed. The Boolean logic operators AND, OR, and NOT were used to combine free-text words (truncated or with wildcards) and MeSH terms. The search was not bound by the year of publication, in which case all articles published and/or reported up to December 30, 2022, were included. The electronic search was exhaustively searched by BGD and DAS through PubMed/MEDLINE, AJOL (African Journal Online), HINARI, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Google electronic databases. In addition, reference lists of already identified articles were also searched to retrieve more relevant studies. The search terms "food taboo" OR "food restriction" OR "food avoidance" OR "food prohibition" AND "prevalence" OR "magnitude" OR "proportion" OR "burden" AND "risk factors" OR "predictors" OR "determinants" AND "pregnant" OR "pregnant woman" OR "pregnant mother" AND "Ethiopia" were used.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort studies from the community and facilities were considered. We used both published and unpublished articles in the English language from Ethiopia. Only studies that estimated the proportion and/or associated factors of food taboos were included. Studies that were duplicated, unrelated, or abstract-only were removed, as well as studies with unclear reporting of the burden and/or factors associated with food taboo practices. Two independent reviewers (HEH and DS) acquired the complete texts of the remaining publications and reviewed them thoroughly before data extraction to ensure their eligibility.

Data extraction procedure and items

Two independent reviewers (BGD and DAS) abstracted data from the primary studies using a standardized data abstraction form devised according to the sequence of variables required. The following characteristics were used to extract data: author's first name, publication date, region; study design (cross-sectional, case–control), sample size, sampling technique, the prevalence of food taboos, odds ratio, and factors that influence food taboos, such as family size, religion, occupation, residence (urban or rural), age, monthly income, education, and ANC follow-up. The degree of agreement between the two independent data extractors is in the range of almost perfect agreement, according to Kappa statistics. We attempted to contact and seek missing outcome data from the original authors by e-mail, and sensitivity analysis was done to find out the robustness of the meta-analysis findings and to show the influence of missing data on review results.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for cross-sectional studies was employed to assess the quality of all the included papers for risk of bias24. Each paper was critically evaluated by two independent reviewers (BGD and HEH). The problem of subjectivities between the two reviewers was solved through discussion and with the involvement of other review teams (HA, DS, and TME). The papers with a quality evaluation score of 6 out of 10 on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale were judged low-risk and included in the systematic review and meta-analysis based on the relevant literature cut-off point (Supplementary 2).

Outcome variable

The primary outcome of this review is the pooled prevalence of food taboo practices among pregnant women at the national level. The numerator was the number of pregnant women who have food taboo practices, while the denominator was the total number of pregnant mothers who participated in the study. The second aim of this review was to identify factors affecting the practice of food taboos among pregnant women in Ethiopia. Unadjusted (raw data) and adjusted odds ratios were extracted for associated factors.

Statistical analysis

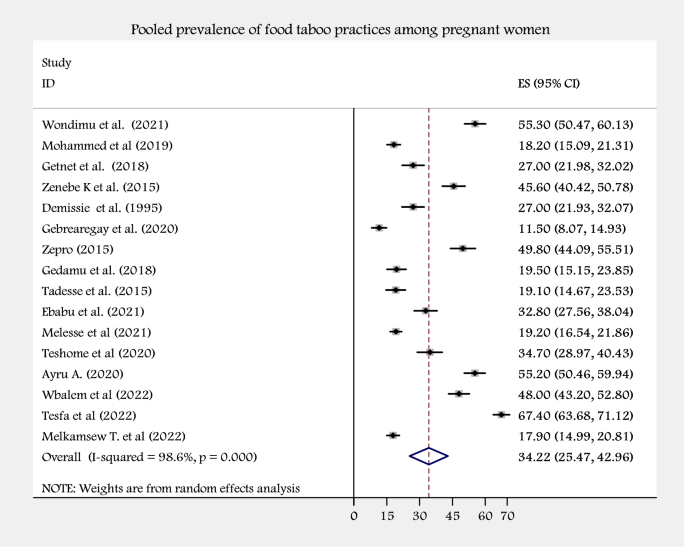

The extracted data was entered into a computer via an Excel sheet for the title, abstract, and full-text screening before being exported to STATA v. 16. The findings were presented in a table and tested using descriptive statistics. The Metaprop program was used to calculate the pooled prevalence of food taboos using the random-effects meta-analysis model. On a forest plot, the single studies and pooled prevalence of food taboo, 95% CI, the author's name, and the publication year were plotted. We performed a subgroup analysis based on the study's publication year, place of residence, and region because the random-effect model with 95% CI had substantial variability among forest plots. Regarding factors influencing food taboo practices, we have pooled the unadjusted odds ratio (raw data) for three factors (age, educational status, and place of residence) (Figs. 6, 7, 9, and 10). However, for ANC follow-up, we pooled both the unadjusted odds ratio (raw data) and the adjusted odds ratio separately, and both were presented to investigate the differences (Figs. 8 and 9). For both adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios, a p-value less than 0.05 with a 95% CI was considered statistically significant. Review Manager 5.4 (RevMan version 5.4)25 was used to identify factors influencing food taboo practices among pregnant women using a random-effects model with an inverse-variance method.

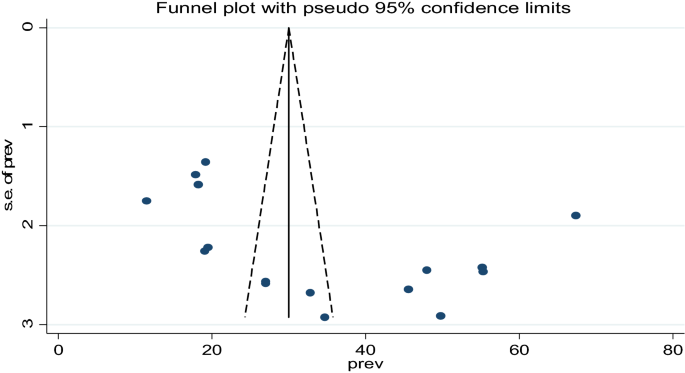

Publication bias and heterogeneity

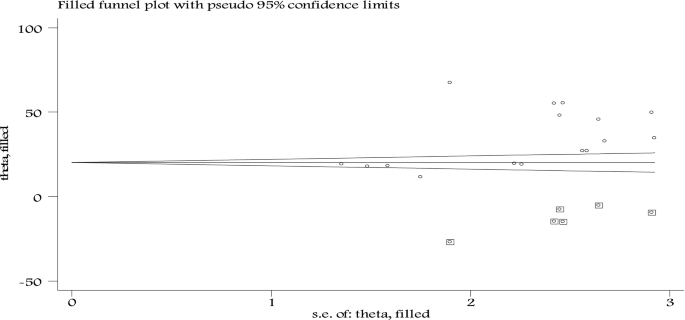

Heterogeneity between the results of the primary studies was assessed using the Cochran’s Q test and quantified with the inverse variance (I2) statistic of 25, 50, and 75% as low, moderate, and severe heterogeneity, respectively, with a p-value less than 0.05. The random-effects model was used to incorporate heterogeneity in meta-analyses. Further, meta-regression was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 4.026 to identify the source of heterogeneity by considering both continuous and categorical data. Region, number of included samples (continuous variable), publication year (during or before 2016 and after 2016), and place of the study (rural/semi-urban, and urban) were considered in the meta-regression. Publication bias was assessed using Begg’s and Egger’s tests with a p-value of less than 0.05 as a cutoff point to declare the presence of publication bias27,28. Due to significant publication bias, a non-parametric Duval and Tweedie’s Trim and Fill analysis was undertaken to manage the publication bias29 (Fig. 4).

Ethics approval

No human subject participant was involved.

Results

Search results

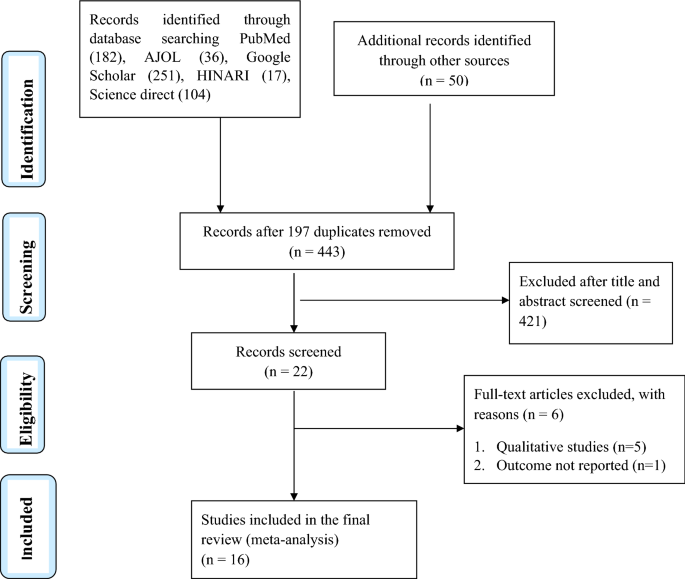

In the first step of our search, 640 articles were systematically retrieved from electronic databases (PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, AJOL (African Journal Online), HINARI, Science Direct, and gray literature from Google) and reference lists of previous studies. From the 640 articles, 197 were excluded due to duplication. Additionally, 421 articles were excluded after we reviewed their titles, abstracts, and full texts and found them to be non-relevant to our review. Among the 22 full-text articles accessed, we excluded six articles as they did not report the prevalence of food taboo practices and/or associated factors among pregnant women15,20,30,31,32,33. Finally, 16 articles were found to be eligible and included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies

After assessment of the titles, abstracts, and full texts, a total of 16 studies that met the inclusion criteria were included in the review. The included studies were conducted between 1995 and 2022 in the English language. Four studies from each of the Oromia14,34,35,36 and Amhara37,38,39,40 regional states as well as eight studies from different regions41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48 of Ethiopia were included. This review includes five community-based studies and eleven institution-based studies, with sample sizes ranging from 276 to 845 in the Dimma district of Gambella42 and West Amhara respectively39. A total sample of 6730 pregnant women was included to estimate the pooled prevalence of food taboo practices among pregnant women at the national level. The lowest level of food taboo practice among pregnant women was reported in Mekelle, Tigray region (12%)41 and the highest level was reported in Gursum district, Somali region (67.4%)47 (Table 1). The quality score of the articles ranged from 6 to 10 out of 10 points (Supplementary 2).

Meta-analysis

The pooled prevalence of food taboo among pregnant women in Ethiopia

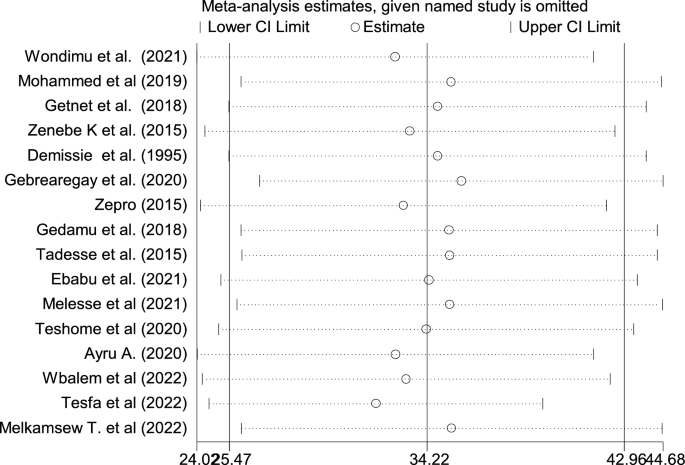

The pooled prevalence of food taboo practices among pregnant women in Ethiopia was 34.22% (with 95% CI 25.47–42.96) using visual forest plots in the random-effect model (Fig. 2). Heterogeneity was seen across the studies, which is detected by the I2 statistic (I2 = 98.6%, p value < 0.0001). Therefore, we employed a random effect meta-analysis model to estimate the pooled prevalence of food taboo practices among pregnant women in Ethiopia (Fig. 2).

Publication bias and Trim-and-fill analysis

Publication bias: A visual inspection of the funnel plot indicated an asymmetrical distribution of studies showing publication bias (Fig. 3). The presence of publication bias was also checked using Begg's test, which shows insignificant publication bias at a p-value = 0.65, whereas Egger’s test indicates the presence of significant publication bias as evidenced by P = 0.04 (Table 2). Therefore, Duval and Tweedie’s Trim and Fill analysis was done (Fig. 4).

Trim-and-fill analysis: Trim-and-fill analysis shows six studies were imputed for missing studies during the analysis, making the total number of studies of 22 and after adjusting publication bias, the estimated pooled awareness of pregnant women toward food taboo practices appeared to be 21.31% (95% CI 10.85 to 31.67%) (Fig. 4).

Meta-regression

A meta-regression was conducted to identify the source of heterogeneity using region, residence, sample size, and publication year as covariates. Meta regression revealed that the prevalence of food taboo practices among pregnant women in Ethiopia was significantly associated with the region of the study, meaning that the prevalence of pregnant women food taboo practices was higher among regions categorized as others (Somali, Benishangul Gumuz, Gambela, and Afar) with a coefficient of 1.40, and a p-value of 0.048 when compared with Addis Ababa city administration (Table 3).

Sub-group analysis

A subgroup analysis was computed to compare the prevalence of food taboo practices by classifying to region, publication year, and residence place. Based on this analysis, the lowest prevalence of food taboo practices among pregnant women was observed in the Tigray region which is 11.5% (with a 95% CI 8.07–14.93) and the highest prevalence was in the Somali region which is 67.4% (with a 95% CI 63.68–71.12). The pooled prevalence of food taboo practices among the studies conducted after the year 2016 was slightly lower than the pooled prevalence from the studies conducted during and before the year 2016. A higher prevalence of food taboo practices was observed in the studies conducted in rural and semi-urban areas (36.6%) than from those conducted in urban study areas (27.02%) (Table 4).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was done to evaluate the effect of a single study on the overall effect estimate. The results indicated that removing a single study did not have a significant influence on pooled prevalence (Fig. 5).

Factors associated with pregnant women's food taboo practices in Ethiopia

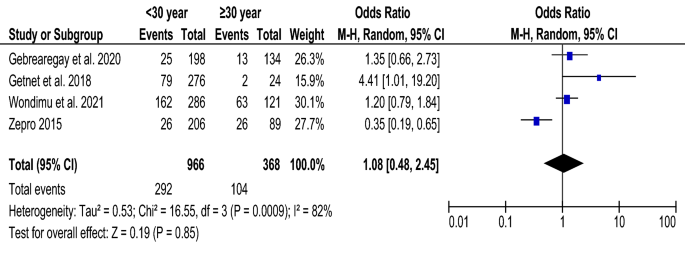

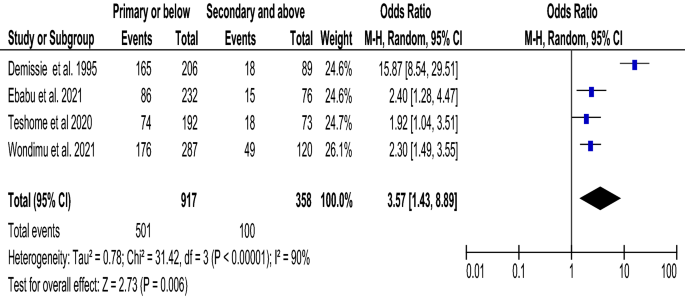

Eleven studies14,34,36,37,41,42,43,44,46,47 were included for the analysis of risk factors for food taboo practices. Accordingly, four risk factors had data that could be used in the quantitative meta-analysis. The pooled odds ratios of four identified risk factors were ranged from 1.08 (for age) to 4.35 (for ANC follow-up) ((Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10).

Age and food taboo practices

A total of four articles14,34,37,41, with 1334 participants were included to assess the association between age and food taboo practices. The pooled odds ratio of included studies shows there is no significant association between the age of pregnant women and food taboo practices (Fig. 6).

Educational status and food taboo practices

Four articles34,42,43,46 with a total of 1275 participants were included in the analysis to detect the association between education and food taboo. Pregnant women with primary and below educational status were 3.57 times more likely (with 95% CI 1.43, 8.89, and I2 = 90%) to practice food taboos during pregnancy than those with secondary and above educational status (Fig. 7).

ANC counseling and food taboo practices

A total of five articles36,37,39,41,44 with 1986 participants were included to determine the association between ANC counseling and food taboo practices using an unadjusted odds ratio. Those mothers who had no ANC follow-up were 4.35 times (with 95% CI 1.12, 16.94, I2 = 97%) more likely to practice food taboo as compared to those who had ANC follow-up (Fig. 8). The pooled AOR (Fig. 9) was 3.48 (with 95% CI 1.92, 6.29; I2 = 81%; n = 4 studies). Both the unadjusted OR and AOR suggest that pregnant women who have no ANC follow-up have significantly higher odds of engaging in taboo food practices when compared to those who have ANC follow-up during their pregnancy.

Place of residence and food taboo practices

Three articles39,46,47 with a total of 1755 participants were included in this analysis. Mothers who live in rural areas were 3.08 times (with 95% CI 1.14, 8.28; I2 = 91%) more likely to practice food taboo during their pregnancy than those who live in urban areas (Fig. 10).

Types of foods considered taboo in Ethiopia and the reasons

Among the 16 included studies, 13 of them assessed the types of prohibited foods for pregnant women and their reasons. From the findings of the studies, seven of them14,34,38,41,43,44,46,48 reported that mainly milk and milk products were prohibited due to beliefs that they plastered on the fetal head, prolonged labor, fear of abortion, making the baby fat, disclosures of the fetus, etc. Fruits and vegetables were also among the most frequently reported food types prohibited by pregnant women due to the most common reasons: attachment to the fetus's body, making a fatty baby, and fear of fetal abnormality. Other types of prohibited foods were meat and eggs due to the fear of producing a large fetus, which is difficult to deliver (Table 5).

Discussion

Ethiopian pregnant women avoid certain foods for a range of reasons, and some of these relate to factors associated with pregnancy outcome, the birthing process, culture, and others to avoid undesirable aesthetic features in the baby14,15. This study, the first systematic review and meta-analysis as far as our knowledge goes, is aimed at estimating the pooled prevalence of food taboo practice and associated factors among pregnant women in Ethiopia. The findings of this meta-analysis showed that the pooled proportion of food taboo practices among pregnant women in Ethiopia is 34.22% (95% CI 25.47–42.96), and after adjustment for publication bias with the trim-and-fill analysis, the pooled food taboo practice of pregnant women was changed to 21.31% (95% CI: 10.85–31.67%). Since we were unable to find another meta-analysis that reported food taboo practices among pregnant women, we didn't compare the findings with similar studies.

The subgroup analysis shows a variation of food taboo practices between regions, with the lowest (11.5%; 95% CI 8.50–15.49) from the Tigray region and the highest (67.4%; 95% CI 63.68–71.12) from the Somali region. The variation could be due to the difference in health service accessibility and utilization. This possible explanation is supported by evidence from the 2019 Ethiopian Mini-Demographic Health Survey (EDHS 2019)49 and recent reports50 on "Progress in Health among Regions of Ethiopia", show regional differences in health service accessibility and utilization. With regard to variation in health service utilization among regions the data from the 2019 Ethiopian Mini-Demographic Health Survey (EDHS 2019)49 show the percentage of pregnant women who received antenatal care from a skilled provider was 70.8% in Oromia and 30.2% in Somali region.

The variation could also be due to the difference in educational status of study participants, which varies among regions. According to the Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey (EDHS 2016)51 the percentage of the female household population who completed primary education ranges from 5.2% in Addis Ababa city administration to 0.7% in the Somali region, which may influence their level of food taboo practices. Furthermore, the possible explanation could be due to socio-cultural differences, as food taboo practices are strongly linked to specific communities' cultural beliefs, as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia is divided into ethnic-linguistic regions.

The pooled prevalence of food taboo practices among the studies conducted after the year 2016 was slightly lower than the pooled prevalence from the studies conducted during and before the year 2016, which was 33.89% and 35.3%, respectively. The possible explanation for the difference could be an improvement in the accessibility of health services, which increases community awareness, particularly through Ethiopian health extension workers. Another reason could be the improvement of the educational levels of women and their partners, as the accessibility of education also shows improvement from time to time.

The findings of this review show the most commonly taboo food types are from four major food groups: proteins, fats, and fruits and vegetables. These include green chili pepper, spinach, lettuce, kale, broccoli, linseed, cabbage, banana, pimento, groundnut, sugarcane, pumpkin, fatty meat, egg, honey, and some cereal products. This is similar to a meta-analysis conducted on food taboos52 and a narrative literature review done in Ethiopia53, which show similar types of foods were prohibited by pregnant women. Among the reasons explained for food taboo, foods getting attached to the fetus's body or head, making the baby gain weight, and fear of fetal abnormality are the most frequent ones. This is similar to a literature review done in Ethiopia53, a meta-analysis conducted worldwide52, and a systematic review conducted in Ethiopia23, which show fear of producing a big fetus, which is difficult during delivery or prolonged labor, fear of abortion, discoloring of the fetus, nausea, abdominal cramps in the mother, and fetal head plastering as the primary drivers of food taboo. Another systematic review supports this, finding that pregnant women's food restrictions are related to their fear of unfavorable pregnancy outcomes, such as the risk of abortion, and are used to avoid child problems such as cutaneous and respiratory disorders54.

Regarding factors associated with food taboo practices, the odds of practicing food taboo during pregnancy were 3.57 times (OR = 3.57; 95% CI 1.43–8.89) higher among pregnant women who have primary and below educational status when compared with those who have secondary and above educational status. This finding is supported by meta-analysis study55 from Ethiopia, which found that pregnant women with lower educational levels have less dietary diversity than those with higher education levels, possibly due to food taboos. This finding also aligned with other primary studies carried out in Sudan and Nigeria, which indicated that higher maternal education was linked to a lower likelihood of practicing food taboos during pregnancy56,57. The possible reason could be the knowledge that they obtained from formal education and reading from different sources about appropriate maternal nutrition.

The ANC follow-up of pregnant women was also significantly associated with food taboo practices during pregnancy. The finding shows pregnant women who had no ANC counseling were 3.48 (AOR = 3.48; 95% CI 1.92–6.92) times more likely to practice food taboos during the pregnancy period than those who had ANC counseling. The finding is in line with a review of evidence on traditional beliefs and practices during the pregnancy period in Asian countries, which suggests that nutrition education should be given to both mothers and husbands in order to alleviate malpractices during pregnancy58. The possible reasons for the association may be due to the nutrition counseling provided by health care providers’ during ANC follow-up.

Another factor that significantly affected the pregnant woman's food taboo practices was her place of residence. Pregnant women who reside in rural areas are 3.08 (OR = 3.08; CI 1.14–8.28) times more likely to practice food taboo than those who live in urban areas. The finding is slightly supported by the meta-analysis study from Ethiopia, which shows pregnant women who reside in rural areas are more likely to get inadequate dietary diversity than those who live in urban55. The probable justification is that urban mothers have more access to health services and health information from different sources than rural pregnant women.

Conclusion

According to the results of this meta-analysis, more than one-third of pregnant Ethiopian women practice food taboo during their pregnancy. Dairy products, fruits, vegetables, meat, eggs, and honey were among the foods prohibited for pregnant women. Food clinging to the fetus's body or head, fear of having a huge fetus that would be difficult to deliver, fear of abortion, and fear of the fetus's appearance were the most often reported reasons for food taboo practices. Educational status, ANC follow-up, and place of residence had a substantial impact on the outcome variable. Therefore, healthcare organizations and other concerned bodies should work on reducing food taboo practices focusing on the identified factors. The findings can be used by healthcare professionals, managers, and policymakers to improve nutrition programs by devising plans and making active efforts to address gaps in dietary practices during pregnancy.

Strength and limitation of the study

We strictly followed PRISMA flow charts and searched a wide range of databases to retrieve related articles. To provide a comprehensive review, additional searches such as hand searching reference lists and citation searching were conducted. Procedures to minimize human error and subjectivity like double independent screening, and double independent quality assessment was used. The limitation of this systematic review and meta-analysis might be due to the cross-sectional nature of the included studies, which couldn’t show the temporal relationship between the outcome and independent variables. Another limitation might be due to the presence of heterogeneity between studies and publication bias, which readers should consider when using this finding. We also have faced difficulties comparing our findings with other findings due to the lack of similar systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Barker, D. J. et al. Maternal nutrition from pre-pregnancy to lactation. Lancet 341, 938–941 (1993).

World Health Organization (WHO). Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. World Healh Organizaion (2016).

Food and Nutrition Unit, Ministry of Planning and Economic Development. Social and Cultural Aspects of Food Consumption Patterns in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (1992).

Mitchell, J., & Mackerras, D. The traditional humoral food habits of pregnant Vietnamese‑Australian women and their effect on birth weight Aust. J. Public Health 19 (1995).

Lakshmi. Food preference and taboos during ANC among the tribal women. J. Commun. Nutr. Health 2 (2013).

Parmar, A., & Khanpara, G. H. A study on taboos and misconceptions associated with pregnancy among rural women of Surendranagar district. Healthline 2 (2013).

von Grebmer, K. et al. Global Hunger Index: The Inequalities of Hunger; International Food Policy Research Institute (Washington, DC, 2017).

Olden, C. D. et al. Seasonal trends of nutrient intake in rainforest communities of north-eastern Madagascar. Public Health Nutr. 22, 2200–2209 (2019).

Ekwochi, U. et al. Food taboos and myths in South Eastern Nigeria: The belief and practice of mothers in the region. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2, 7 (2016).

Ugwa, E. A. Nutritional practices and taboos among pregnant women attending antenatal care at general hospital in Kano, Northwest Nigeria. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 6, 109–114 (2016).

Martínez Pérez, G., & Pascual García, A. Nutritional taboos among the Fullas in Upper River region, the Gambia J. Anthropol. (2013).

Kariuki, L. W. et al. Role of food taboos in energy, macro and micronutrient intake of pregnant women in western Kenya. Nutr. Food Sci. 47, 795–807 (2017).

Cherkos, T. M., Hailemichael, T., Sinamo, S., Loha, M. & Woldeyes, L. Role of nutrition education to overcome food taboos and improve iron tablets demand during pregnancy in Ethiopia: Wonchi District. Ann. Nut. Metab. 63, 1738 (2013).

Zepro, N. B. Food taboos and misconceptions among pregnant women of Shashemene District. Ethiopia Sci. J. Public Health 3, 410–416 (2015).

Asilevski, V. & Carolan-Olah, M. Food taboos and nutrition-related pregnancy concerns among Ethiopian women. J. Clin. Nurs 25, 3069–3075 (2016).

World Health Organization (WHO). Essential Nutrition Actions: Improving Maternal, Newborn, Infant and Young Child Health and Nutrition; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland (2013).

WHO/UNICEF. Methodology for Monitoring Progress Towards the Global Nutrition Targets for 2025—Technical Report. World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Technical Expert Advisory Group on Nutrition Monitoring (TEAM). Geneva (2017 ).

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018. Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition (2018).

Mohammed, S. H., Taye, H., Larijani, B. & Esmaillzadeh, A. Food taboo among pregnant Ethiopian women: magnitude, drivers, and association with anemia. Nutr. J. 18, 19 (2019).

Hadush, Z., Birhanu, Z., Chaka, M. & Gebreyesus, H. Foods tabooed for pregnant women in Abala district of Afar region, Ethiopia: An inductive qualitative study. BMC Nutr. 3(1), 40 (2017).

Zerfu, T. A., Umeta, M. & Baye, K. Dietary habits, food taboos, and perceptions towards weight gain during pregnancy in Arsi, rural Central Ethiopia: A qualitative cross-sectional study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 35(1), 22–22 (2016).

Getnet, W., Aycheh, W., & Tessema. T. Determinants of food taboos in the pregnant women of the Awabel District, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Regional State in Ethiopia. Adv. Public Health (2018).

Gebremariam, H. Food taboos during pregnancy and its consequence for the mother, infant and child in Ethiopia: A systemic review. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. Fund. 13(02) (2017) www.ijpbsf.com (An Indexed, Referred and Impact Factor Journal) ISSN: 2278-3997.

Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 603–605 (2010).

Review Manager software (RevMan version 5.4.1) [Internet]. https://medium.com/mlearning-ai/reviewmanager-software-revman-version-5-4-1-933c3d9f7a2f.

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 4.0) [Internet]. https://www.meta-analysis.com/pages/cma4_manual.php.

Sterne, J. A. E. M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 54(2), 1046–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00377-8 (2001).

Sterne, J. A. E. M. Regression methods to detect publication and other bias in meta-analysis. Publication bias in meta-analysis: Prevention, assessment and adjustments 99–110.

Duval, S. & Tweedie, R. A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in metaanalysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 95(449), 89–98 (2000).

Zerfu, T. A., Umeta, M. & Baye, K. Dietary habits, food taboos, and perceptions towards weight gain during pregnancy in Arsi, rural central Ethiopia: A qualitative cross-sectional study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 35, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-016-0059-8 (2016).

Tsegaye, D., Tamiru, D. & Belachew, T. Food-related taboos and misconceptions during pregnancy among rural communities of Illu Aba Bor zone, Southwest Ethiopia. A community based qualitative cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 309. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03778-6 (2021).

Tilahun, R., Aregawi, S., Molla, W. Food taboo and myth among pregnant mothers in Gedeo Zone, South Ethiopia: a qualitative study (unpublished). https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1556900/v1.

Kassahun, G., Wakgari, N. & Abrham, R. Patterns and predictive factors of unhealthy practice among mothers during pregnancy, childbirth, postnatal and newborn care in Southern Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes 12, 594. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4631-3 (2019).

Wondimu, R., Tesfahun, E. & Kaba, Z. Food taboo and its associated factors among pregnant women in SendafaBeke Town, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Soc. 9, 75 (2021).

Tola, T. N. & Tadesse, A. H. Cultural malpractices during pregnancy, child birth and postnatal period among women of child bearing age in Limmu Genet Town, Southwest Ethiopia. Sci. J. Public Health 3, 752–756 (2015).

Wbalem, A. et al. Food taboos among pregnant women and associated factors in eastern Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 10, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121221133935 (2022).

Getnet, W., Aycheh, W. & Tessema, T. Determinants of food taboos in the pregnant women of the Awabel District, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Regional State in Ethiopia. Adv. Public Health 2018 (2018).

Gedamu, H., Tsegaw, A., & Debebe, E. The prevalence of traditional malpractice during pregnancy, child birth, and postnatal period among women of childbearing age in Meshenti Town. Int. J. Reprod. Med. 2018 (2016).

Melesse, M. et al. Cultural malpractices during labor/delivery and associated factors among women who had at least one history of delivery in selected Zones of Amhara region, North West Ethiopia: Community based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 1–12 (2021).

Zenebe, K. et al. Prevalence of cultural malpractice and associated factors among women attending MCH Clinic at Debretabor Governmental Health Institutions South Gondar, Amhara Region, North West Ethiopia, 2015. Gynecol. Obstet. (Sunnyvale) 6, 2161–09321000371 (2016).

Tela, F. G. G., WeldegerimaBeyene, L. & Asfaw, S. Food taboos and related misperceptions during pregnancy in Mekelle city, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 15, e0239451 (2020).

Teshome, A., Zinab, B., Wakjira, T. & Tamiru, D. Factors associated with food taboos among pregnant women in the Dimma district, Gambella, Ethiopia. Afr. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 14, 1–9 (2020).

Ebabu, A. & Muhammed, M. Traditional practice affecting maternal health in pastoralist community of Afar Region, Ethiopia: A facility-based cross-sectional study. J. Midwifery Reprod. Health 9, 2817–2827 (2021).

Alga, A. Food taboo and associated factors among pregnant women attanding ANC service in Mandura Woreda, Benishangul Gumuz Regional State, Northwest Ethiopia (2020).

Mohammed, S. H., Taye, H. L., Esmaillzadeh, B. & Ahmad,. Food taboo among pregnant Ethiopian women: Magnitude, drivers, and association with anemia. Nutr. J. 18, 1–9 (2019).

Demissie, T., Muroki, N., Kogi-Makau, W. Food taboos among pregnant women in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia. Ethiopian J. Health Dev. 12 (1998).

Tesfa, M. et al. Food taboos and associated factors among agro-pastoralist pregnant women: A community-based cross-sectional study in Eastern Ethiopia. Heliyon 8, e10923 (2022).

Tesfaye, M., Solomon, N., Getachew, D. & Biru, Y. B. Prevalence of harmful traditional practices during pregnancy and associated factors in Southwest Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 12, e063328 (2022).

Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. 2021. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Final Report. Rockville, Maryland: EPHI and ICF.

Misganaw, A. et al. Progress in health among regions of Ethiopia, 1990–2019: A subnational country analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 399(10332), 1322–1335 (2022).

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. 2016. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville. Maryland: CSA and ICF

Maggiulli, O., Rufo, F., Johns, S. E. & Wells, J. C. K. Food taboos during pregnancy: Meta-analysis on cross cultural differences suggests specific, diet-related pressures on childbirth among agriculturalists. PeerJ 10, e13633. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13633 (2022).

Kibr, G. A narrative review of nutritional malpractices, motivational drivers, and consequences in pregnant women: Evidence from recent literature and program implications in Ethiopia. Hindawi Sci. World J. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5580039 (2021).

de Diego-Cordero, R. et al. The role of cultural beliefs on eating patterns and food practices among pregnant women: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa119 (2021).

Hidru, H. D. et al. Burden and determinant of inadequate dietary diversity among pregnant women in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hindawi J. Nutr. Metab. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1272393 (2020).

Tahir, H. M. H. et al. Food taboos among pregnant women in health centers, Khartoum State-Sudan. Int. J. Sci. Healthc. 3, 13–25 (2018).

Sholeye, O. O., Badejo, C. A. & Jeminusi, O. A. Dietary habits of pregnant women in Ogun-East Senatorial Zone, Ogun State, Nigeria: A comparative study. Int. J. Nutr. Metab. 4, 42–49 (2014).

Mellissa Withers, N. K. Esther Lim, Traditional beliefs and practices in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum: A review of the evidence from Asian countries. Midwifery 56, 158–170 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all authors of studies included in this systematic review and Meta analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B. G. selected the studies. B. G, H.E.H, T. M. E, and A.T. performed the literature search and helped with study selection process. B. G. and H.E.H. extracted the data. B. G., H.E.H., T. M. E., H. A. E., D. S., and D. A. designed the study. B. G., H.E.H., D. S., and D. A. software utilization. B. G., H.E.H., T. M. E., H.A.E., A. T., D.S., and D. A. performed the statistical analyses. B. G. wrote the initial draft. B. G., H.E.H., T. M. E., H.A.E., D.S., D. A., and A. T. interpreted data and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Debela, B.G., Sisay, D., Hareru, H.E. et al. Food taboo practices and associated factors among pregnant women in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 13, 4376 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30852-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30852-0

This article is cited by

-

Effect of nutrition education integrating the health belief model and theory of planned behavior on dietary diversity of pregnant women in Southeast Ethiopia: a cluster randomized controlled trial

Nutrition Journal (2024)

-

Prevalence and Associated Factors of Cultural Malpractice During the Perinatal Period in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Reproductive Sciences (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.