Abstract

In this study, 2-[(E)-(hexylimino)methyl] phenol (SA-Hex-SF) was synthesized by adding salicylaldehyde (SA) and n-hexylamine (Hex-NH2), which was subsequently reduced by sodium borohydride to produce 2-[(hexylamino)methyl] phenol (SA-Hex-NH). Finally, the SA-Hex-NH reacted with formaldehyde to give a benzoxazine monomer (SA-Hex-BZ). Then, the monomer was thermally polymerized at 210 °C to produce the poly(SA-Hex-BZ). The chemical composition of SA-Hex-BZ was examined using FT-IR, 1H, and 13C NMR spectroscopy. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and X-ray Diffraction (XRD), respectively, were used to examine the thermal behavior, surface morphology, and crystallinity of the SA-Hex-BZ and its PBZ polymer. Mild steel (MS) was coated by poly(SA-Hex-BZ) which was quickly prepared using spray coating and thermal curing techniques (MS). Finally, the electrochemical tests were used to evaluate the poly(SA-Hex-BZ)-coating on MS as anti-corrosion capabilities. According to this study, the poly(SA-Hex-BZ) coating was hydrophobic, and corrosion efficiency reached 91.7%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

By anticipating the arrival of destructive specialists and working as linked current boundaries, organic coatings were frequently used to resist corrosion in metals and steel1. The main strategies for preventing mild steel from unfavorable corrosion during industrial processes include organic coatings that resist corrosion. This keeping in contact with resistance inhibition and the creation of a barrier that prevents the passage of corrosive species and then were thought to be an affordable and practical solution2,3. The rates of ion transport and moisture through a coating's polymer network were frequently used to characterize a coating's protective barrier properties3. Relatively high-risk PBZ coatings could adhere to metal substrates better and resist corrosion when particular functional groups were incorporated into them4,5. Recently, steel surfaces were covered with protective passive oxide layers composed of PBZ-based electroactive species to inhibit corrosion6,7. As an analogy, covering mild steel (MS) with curable polybenzoxazine (PBA-ddm) achieved good corrosion inhibition and two-orders of magnitude reduction in the corrosion rate compared to that generated by the uncoated MS7. The crosslinking network structure of polybenzoxazines (PBZs) involves intra and intermolecular hydrogen linkages that offered polybenzoxazines many desirable characteristics, outstanding mechanical and insulating characteristics8,9, in addition to high thermal stability, high glass transition temperatures, high char yields, almost little shrinkage upon polymerization, low surface free energy, and higher moisture absorption. Benzoxazine monomers were commonly produced via Mannich reactions of phenols, primary amines, and formaldehyde, and could readily polymerize by thermal curing without a catalyst and without releasing any byproducts in their ring-opening polymerization (ROP)10,11. High-performance polymers with good mechanical, chemical and thermal properties include PBZs and aromatic polyimides12. Various ways were employed to reduce base metal corrosion, among which inhibitors were one of the simplest and utmost well-known13. The performance of this monomer and the resultant PBZs might be enhanced by making use of the significant levels of structural flexibility in design and functionalization that were present in benzoxazine monomers. This increased the variety of possible uses for these monomers. When a sulfonic acid unit was inserted into the benzoxazine backbone, for instance, the resulting PBZs exhibited excellent acid resistance and low methanol permeability with good thermal stability in methanol-based fuel cells; they were a good material for hydrogen membranes14. The soybean (SE) was utilized to inhibit corrosion on carbon steel in a sulfuric media15. PBZ was found to be a promising matrix material, but even in need to be utilized more efficiently in the space environment, it needs to be strengthened against atomic oxygen (AO), ultraviolet (UV), ionizing, vacuum-ultraviolet (VUV), and heat cycles16,17. Various materials, particularly polymers, dyes, pigments, and semiconductor devices, were degraded by UV light18. Polymeric materials survived permanent deterioration, as a result, impacting their properties19,20. Manufacturers used polybenzoxazine coatings, such as electronics, fire resistance, and super hydrophobic coatings at elevated temperatures21,22,23. To increase a polybenzoxazines variety of applications, silane-functionalized polybenzoxazine anticorrosion coating was applied to steel surfaces. This coating effectively decreased the rate of corrosion on steel since the corrosion current was five times lower than that of a pure MS surface24. Upon the MS surface, hydrophobic polybenzoxazine (PBA-a) coatings based on bisphenol A were produced. According to studies, the PBA-a coating into MS exhibited superior resistance to corrosion to the epoxy resin coating7. P-phenylene diamine benzoxazine and commercial bisphenol A based on benzoxazine also was utilized as a corrosion-resistant coating on 1050 aluminum alloy25. Recent studies have shown the efficiency of PBZ derivatives developed from bio-based materials, including vegetable oil, in inhibiting the corrosion of steel covered with Zn–Mg–Al alloy15,26,27. These studies revealed that PBZs could be used as corrosive environmental materials28. A new type of PBZ precursor called main-chain-type benzoxazine polymer (MCBP) contained cross-linkable benzoxazine rings within the polymer backbone29. Using diamine, bisphenol A, as well as paraformaldehyde, high molecular weight PBZ was synthesized30. According to the results of toughness tests, higher molecular weight PBZ thermosets produced from MCBP are more durable than any of those prepared from more common, lower molecular weight PBZ. An isomer combination of paraformaldehyde, diamines, and bisphenol-F was used to produce good physical and mechanical characteristics with MCBPs31. Pyrimidine derivatives also were reported as an effective ecofriendly corrosion inhibitor in acidic environments32. Improvement of mild steel's ability to resist corrosion in an acid environment by using unique carbon dots as a green corrosion inhibitor33. Herein, we synthesized novel benzoxazine monomer (SA-Hex-BZ) through Schiff base condensation of n-hexyl amine with SA followed by reduction of Schiff base compound by sodium borohydride and finally, ring closing by formaldehyde in 1,4-dioxane (DO) at 100 °C [Fig. 1], which their chemical structures were proved by FTIR 1H and 13CNMR. The thermal stabilities, thermal curing behavior, and surface morphology of the SA-Hex-BZ and poly(SA-Hex-BZ) were confirmed by TGA, DSC, and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). On the MS surface, the SA-Hex-BZ monomer was sprayed on and thermally cured. Open-circuit potentials (OCPs) results showed that our poly(SA-Hex-BZ) coating was excellent anti-corrosion performance.

Experimental section

Materials

Salicylaldehyde (SA), n-hexylamine (Hex-NH2), ethanol, sodium hydroxide (NaOH), anhydrous sodium sulfate, formaldehyde, 1,4-dioxane (DO), chloroform, sodium borohydride (NaBH4) and dilute hydrochloric acid were purchased from Acros. All melting points were recorded and corrected on the Melt-Temp II melting point instrument. The chemicals and solvents used in this experiment were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and are all of the analytical grades.

Synthesis of 2-[(E)-(hexylimino)methyl] phenol [SA-Hex-SF]

Hex-NH2 (40 mmol, 5.25 mL) was stirred slowly to a solution of SA (40 mmol, 4.2 mL) in abs. ethanol (30 mL) for 5 h at 60 °C. The viscous liquid product was transparent and yellow in color [Fig. 1b]. b.p: 78–79 °C. FTIR (KBr, cm−1, Fig. 2a): 3550–3300 (OH), 1633 (CH=N).1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, δ, ppm, Fig. 3): 13.85 (s, 1H, -OH), 8.35 (s, 1H, –CH=N–), 6.80–7.40 (m, 4H, ArH), 3.60 (t, 2H, –CH2–), 1.70 (m, 2H, –CH2–), 1.40 (m, 4H, 3–CH2–), 1.0 (t, 3H, –CH3), 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, δ, ppm, Fig. 4): on decoupled 163 (–CH=N–), 120–161 (6C aromatic) which become (4C aromatic) on dept due to 2C have no proton.

Synthesis of 2[(hexylamino)methyl]phenol [SA-Hex-NH]

SA-Hex-NH (20 mmol, 4.10 g) and excess NaBH4 (0.76 g) were added slowly with stirring for 3 h at room temperature. Then, 100 mL of water was added when the reduction was completed, and the product was extracted with chloroform, washed with water, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated until dry. The viscous liquid product tas transparent and yellow in color [Fig. 1b]. FTIR (KBr, cm−1, Fig. 2b): 3212 (NH, stretching), 3100–3300 (OH, broad) due to inter and intramolecular hydrogen bond, 1572 (–NH–, bending). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, δ, ppm, Fig. 5): 7.80 (s, 1H, OH), 6.77–7.30 (m, 4H, ArH), 4.0 (s, 2H, –CH2–), 2.70 (t, 2H, –CH2–), 1.55 (m, 2H, –CH2–), 1.35 (m, 6H, 3–CH2–), 0.5 (t, 3H, –CH3).

Synthesis of n-hexylamine based-benzoxazine (SA-Hex-BZ)

SA-Hex-NH (30 mmol, 6.21 g) was stirred with an excess of formaldehyde (32 mmol, 1.14 mL) in 30 mL of DO at 100 °C for 27 h. The residue was dissolved in chloroform and washed with NaOH (20 mL, 2 M) solution just after the solvent had already been evaporated. Over sodium sulfate, the organic layer was dried and extracted to dryness. The product was a brownish liquid oil [Fig. 1d]. The physical properties of SA-Hex-Bz are listed in Table 1. FTIR (KBr, cm−1, Fig. 2c), 1236 (COC antisymmetric stretching), 1107 (COC symmetric stretching), and 930 (oxazine ring). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, δ, ppm, Fig. 6): 6.75–7.40 (m, 4H, ArH), 4.90 (s, 2H, OCH2N), 4.0 (s, 2H, ArCH2N=), 2.20 (t, 2H, –CH2–), 1.50 (m, 8H, 4–CH2–), 0.95 (t, 3H, –CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, δ, ppm, Fig. 7): 129.93–118.12 (aromatic), 84.63 (-OCH2N-), 51.41 (ArCH2N-).

Preparation of poly(SA-Hex-BZ)

In accordance with the procedure for the synthesis of poly(SA-Hex-BZ), the SA-Hex-BZ monomer was cured in a furnace at 210 °C; for 2 to afford poly(SA-Hex-BZ) as a black solid, as presented in Fig. 1e. The physical properties of poly(SA-Hex-BZ) are listed in Table 1.

Preparing studied surface and tested media

0.17% C, 0.072% Ni, 0.022% Si, 0.0017% Al, 0.011% Mo, 0.010% P, 0.71% Mn, 0.182% Cu, 0.022% F, 0.045% Cr, 0.011% Sn and 98.74% Fe constitute the mild steel (MS) specimen34. We cut the MS specimens into 1 × 1 × 1 cm3 blocks for the electrochemical measurements. Every specimen placed through the testing process has its surfaces cleaned with acetone first, then polished with emery polishing paper of different grades, including 1200 and 1400, before even being dried. The corrosive solutions are made with analytical grade 97% H2SO4 (Sigma-Aldrich Laborchemikalien, Germany) and are subsequently diluted with bi-distilled water before usage.

Corrosion tests

The SA-Hex-BZ and poly(SA-Hex-BZ) were dissolved in 200 ppm chloroform to create the inhibitor's solution. The method employed in the studies involves spraying monomer on the surface of MS and curing it at 210 °C for two hours. The resultant layer has a 4-µm thickness that forms a thin coating (poly(SA-Hex-BZ)) on the mild steel electrode (using a micrometer caliper). The corrosion-causing medium must be immersed to allow the open circuit potential to proceed.

Characterization

FTIR spectra were recorded using a Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR spectrophotometer with a resolution of 4 cm–1 through the KBr disk method. 13C Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded using an INOVA 500 instrument with CDCl3 as the solvent and TMS as the external standard; chemical shifts were reported in parts per million (ppm). The thermal stabilities of the samples were examined under an N2 using a TG Q-50 thermogravimetric analyzer; each cured sample (ca. 5 mg) was placed in a Pt cell and heated at a rate of 20 °C min–1 from 100 to 800 °C under a N2 flow rate of 60 mL min–1. Wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) patterns were measured using the wiggler beamline BL17A1 of the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC), Taiwan; a triangular bent Si (111) single crystal was used to give a monochromated beam having a wavelength (λ) of 1.33 Å. The morphologies of the samples were examined using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; JEOL JSM7610F). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was collected on K-ALPHA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with monochromatic X-ray Al K-alpha radiation − 10 to 1350 eV spot size 400 micron at pressure 9–10 bar with full spectrum pass energy 200 eV and at narrow spectrum 50 eV. The Raman spectra were investigated using Horiba Jobin–Yvon HR800 Raman Spectrometer with 633 nm laser, 10 s accumulated scans repeated 20 times, and a 50× magnification lens.

Results and discussion

Thermal curing behavior of SA-Hex-BZ monomer to produce poly(SA-Hex-BZ)

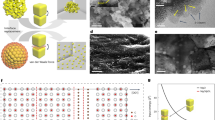

Herein, salicylaldehyde (SA) [Fig. 1a] and n-hexylamine (Hex-NH2) were used to produce SA-Hex-SF [Fig. 1b], which was then reduced by NaBH4 to afford SA-Hex-NH [Fig. 1c], and finally the SA-Hex-NH reacted with CH2O to afford a new benzoxazine precursor called SA-Hex-BZ) [Fig. 1d]. Then, the poly(SA-Hex-BZ) was prepared through thermal curing polymerization of its monomer at benzoxazine at 210 °C [Fig. 1e]. The FTIR spectrum of SA-Hex-BZ features characteristics absorption signals centered at 1236 and 1107 cm−1, corresponding to asymmetric and symmetric C–O–C stretching, respectively, which occurs slight disappearance or changes in its intensity, as well as the intensity of peak for OH group [Fig. 2d], was increased, subsequent thermal curing 210 °C to give poly(SA-Hex-BZ). The FT-IR analysis confirmed the ring-opening polymerization of the SA-Hex-BZ monomer, which revealed that the oxazine ring's absorption band at 933 cm−1 practically vanished after thermal curing. Figure S1 presents the Raman profile of poly(SA-Hex-BZ) after thermal polymerization of SA-Hex-BZ monomer at 210 °C. As observed, The bands (1236, 1107, and 930 cm−1) from the benzoxazine ring are consumed during the ring opening reaction of the SA-Hex-BZ monomer. The peak at 1611 cm−1 attributed to the C=C from the benzene ring still existed and was used as an internal standard because the aromatic ring is not consumed during the thermal polymerization of the BZ monomer. The peaks of C1s, N1s, and O1s in the poly(SA-Hex-BZ) sample were found at 285.32 eV, 400.07 eV, and 532.97 eV; respectively, based on XPS analysis [Figure S2]. Figure 8 shows DSC thermograms of the SA-Hex-BZ and poly(SA-Hex-BZ). As shown in the DSC profile of SA-Hex-BZ, the endothermic peak may be attributed to the melting point, and the exothermic peak (ROP) was 179 °C and 198 °C, respectively35. As compared to prior imide-functionalized benzoxazine investigations that had been employed in the manufacture of high-performance materials, this study's exothermic peaks manifested at lower temperatures22. After curing of SA-Hex-BZ at 210 °C, the exothermic peaks of SA-Hex-BZ entirely vanished, suggesting full ROP. Additionally, the glass transition temperature (Tg) of poly(SA-Hex-BZ) after curing at 210 °C was computed in Table 2, at which the Tg value of poly(SA-Hex-BZ) was 217 °C. These results are the average from three different observations. Hence, the Tg value in our new poly(SA-Hex-BZ) was higher compared to the cross-linked materials reported NDOPodaBz (205 °C after curing at 210 °C)36. We were able to explain the high value of Tg of poly(SA-Hex-BZ) by referring to the high density of inter- and intra-molecular hydrogen bonds between the phenolic OH groups and the nitrogen atoms in Mannich bridges. The stability of the SA-Hex-BZ monomer as well as its corresponding poly(SA-Hex-BZ) obtained after curing at 210 °C was studied using TGA (Fig. 9, Table 2). We considered the temperature for 5%, 10%, and 50% weight loss as (Td5 and Td10, Td50, respectively). As the curing temperature increased, highly cross-linked thermosets developed, increasing the data of Td5, Td10, Td50, and char yields. After curing the monomer at 210 °C, the data of Td5, Td10, Td50, and char yields at 800 °C have been 332, 409, 635 °C, and 51.89 wt.%, respectively; for SA-Hex-BZ monomer data of Td5, Td10, Td50, and the char yields have been 116, 134, 188 °C, and 0.85 wt.%, respectively. Thus, the thermal stabilities of our new poly(SA-Hex-BZ) were higher than that of the SA-Hex-BZ. The XRD profiles of the SA-Hex-BZ and poly(SA-Hex-BZ) obtained after thermal curing at 210 °C showed that the signal at 2 = 11° refers to the (002) plane, which represents irregular and amorphous carbons [Fig. 10]. The SEM images [Fig. 11] of poly(SA-Hex-BZ), after thermal curing at 180 and 210 °C, the SEM images displayed that the poly(SA-Hex-BZ) particles were placed next to each other like ropes.

Electrochemical techniques

Open circuit potential

Figure 12 shows the curves of E (mV) vs. time (min.) at current zero for MS immersed in the blank solution and 200 ppm of the tested inhibitors (SA-Hex-BZ and poly(SA-Hex-BZ). It was clear that for blank solution curves, Es.s moves to a negative potential than Eim. This change is owing to the oxide film deteriorating from the surface of MS until it enters the corrosion cell's Es.s. The addition of various concentrations of the testing inhibitors resulted in a shift of Es.s value to a more positive potential than the uncoated MS. The latter result from such an inhibitor molecule layer being adsorbed on the MS surface's active sites. Data derived from open circuit potential (OCP) are displayed in Table 3.

Tafel polarization

The Tafel plot polarisation method estimates the corrosion current, potential, rate, and inhibition efficiency of mild steel that has been subjected to acidic conditions both with and without inhibitors within a range of 250 mV versus ES.S and at a scan rate of between 0.166 and 0.3 mV/S. The corrosion rate (denoted by CR) and the inhibitor efficiency percent (IE %), can be determined using Eqs. (1) and (2).37

where CR was the (corrosion rate mpy), Icorr was the (corrosion current density μA/cm2), which records the current value at which the corrosion process takes place, Eq. Wt. was the equivalent weight of the metal (g/equivalent) equal to 55.8 atomic mass, A is the area (cm2) immersed in tested solutions, ρ is the density (gm/cm3) equal to 7.874 g/cm3, and 0.13 was the metric and time conversion factor.

Figure 13 shows potentiodynamic polarisation curves of mild steel corrosion in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution with and without inhibitors. It was observed that the presence of SA-Hex-BZ and poly(SA-Hex-BZ), caused shifting in Tafel slopes. This indicated that: (1) the adhesion of inhibitor molecules to the MS electrodes' surface and (2) the Ecorr of used inhibitors differs positively from that of the blank solution, and the difference doesn't reach 85 mV, which proved that these inhibitors are mixed ones and are reduced in anodic and cathodic Tafel slope38. Table 4 records the parameters extracted from TF such as Icorr, Ecorr, CR, IE%, and θ of MS with and without inhibitors. In the absence of studied inhibitors, Icorr increased to reach 2990 (µA/cm2), and CR increased to reach 2488 mpy. In addition, with the inhibitors to the blank solution, a decrease in each of Icorr, CR, and IE% was observed. The poly(SA-Hex-BZ) exhibits more inhibition efficiency than the SA-Hex-BZ monomer (91.7% and 84.4%, respectively). The high inhibition efficiency of poly(SA-Hex-BZ) (91.7%) compared with SA-Hex-BZ monomer (84.4%) was caused, upon ring-opening of the oxazine units, there was a higher cross-linking density and intra–intermolecular hydrogen bonding in the earlier. The corrosion behavior of MS in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution in the absence and presence of poly(SA-Hex-BZ) was investigated by the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) method at 25 °C. Nyquist plots of MS in 1.0 M H2SO4 solution with and without the poly(SA-Hex-BZ) is given in Figure S3, which shows a single semicircle and reveals that the charge transfer process is occurring at the electrode/solution interface. The addition of the poly(SA-Hex-BZ) does not change the impedance shape, but the diameter of this semicircle increases in the presence of poly(SA-Hex-BZ) than in its absence. It is clear that the impedance response for steel in HCl changes significantly in the presence of poly(SA-Hex-BZ) and the corrosion of steel is inhibited in the presence of the poly(SA-Hex-BZ). Figure S4 displayed the surface morphology of poly(SA-Hex-BZ) coating on mild steel after curing SA-Hex-BZ monomer at 210 °C for 2 h and immersing coated MS with poly(SA-Hex-BZ) in corrosive solution 1.0 M H2SO4 solution. The SEM images revealed that there are no defects like pores or cracks appearing in the morphology of poly(SA-Hex-BZ) coatings after the corrosion process. Moreover, The surface is lightly damaged, which indicates that poly(SA-Hex-BZ) coating on MS can effectively inhibit the corrosion of MS in the aggressive H2SO4 solution. This emerged from coordination interaction among poly(SA-Hex-BZ) coatings and MS surfaces, that have high adsorbing properties.

Corrosion protection mechanism

The SA-Hex-BZ precursor was capable of forming a compact crosslinking network after thermal curing. As such coating was completely cured at 210 °C for 2 h and exhibited hydrophobic qualities to produce poly(SA-Hex-BZ), which considerably improved the corrosion resistance of MS. Figure 14 indicates that the barrier ability was principally responsible for the poly(SA-Hex-BZ) coating's anti-corrosive property after curing. The hydrophobic poly(SA-Hex-BZ) coating with a dense crosslinked network can enhance corrosion reaction barrier ability and reduce corrosive medium penetration compared to hydrophilic bare MS. From Table 5, it can be noticed that our polymer named poly(SA-Hex-BZ) has the highest inhibition effect from other different inhibitors in the same corrosive medium.

Conclusions

In summary, the SA-Hex-BZ monomer was prepared through three steps, including condensation, reduction, and ring-closing reaction, as displayed in Fig. 1. DSC and TGA analyses revealed that the poly(SA-Hex-BZ) produced following the thermal curing of SA-Hex-BZ at 210 °C had a high value of Tg and char yield due to the higher crosslinking density and degree of intramolecular hydrogen bonding in poly(SA-Hex-BZ). In 0.1 M H2SO4 solution, MS coated with poly(SA-Hex-BZ) revealed superior resistance to corrosion than bare MS. This emerged from coordination interaction among poly(SA-Hex-BZ) coatings and MS surfaces, that have high adsorbing properties. It can be noticed that our polymer named poly(SA-Hex-BZ) has the highest inhibition effect. Finally, incorporating the hexyl group into benzoxazine coatings appears to be a great option to provide high-performance corrosion protection.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Zhou, C., Lin, J., Lu, X. & Xin, Z. Enhanced corrosion resistance of polybenzoxazine coatings by epoxy incorporation. RSC Adv. 6(34), 28428–28434. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA02215D (2016).

Sayed, M. M., Abdel-Hakim, M., Mahross, M. H. & Aly, K. I. Synthesis, physico-chemical characterization, and environmental applications of meso porous crosslinked poly (azomethine-sulfone)s. Sci. Rep. 12, 12878. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17042-0 (2022).

Ren, S., Cui, M., Chen, X., Mei, S. & Qiang, Y. Comparative study on corrosion inhibition of N doped and N, S codoped carbon dots for carbon steel in strong acidic solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 628(B), 384–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2022.08.070 (2022).

Aly, K. I. et al. Salicylaldehyde azine-functionalized polybenzoxazine: Synthesis, characterization, and its nanocomposites as coatings for inhibiting the mild steel corrosion. Prog. Org. Coat. 138, 105385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.105385 (2020).

Krishnan, S. et al. Silane-functionalized polybenzoxazines: a superior corrosion resistant coating for steel plates. Mater. Corros. 68(12), 1343–1354. https://doi.org/10.1002/maco.201709587 (2017).

Li, S., Zhao, C., Wang, Y., Li, H. & Li, Y. Synthesis and electrochemical properties of electroactive aniline-dimer-based benzoxazines for advanced corrosion-resistant coating. J. Mater. Sci. 53(1), 7344–7356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-018-2113-y (2018).

Lu, X. et al. Crosslinked main-chain-type polybenzoxazine coatings for corrosion protection of mild steel. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 14(4), 937–944. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11998-016-9902-5 (2017).

Arslan, M., Kiskan, B. & Yagci, Y. Benzoxazine-based thermoset with autonomous self-healing and shape recovery. Macromolecules 51(24), 10095–10103. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.8b02137 (2018).

Mohamed, M. G. & Kuo, S.-W. Crown ether-functionalized polybenzoxazine for metal ion adsorption. Macromolecules 53(7), 2420–2429. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.macromol.9b02519 (2020).

Lin, R. C., Mohamed, M. G. & Kuo, S.-W. Benzoxazine/triphenylamine-based dendrimers prepared through facile one-pot mannich condensations. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 38(16), 1700251. https://doi.org/10.1002/marc.201700251 (2017).

Mohamed, M. G., Kuo, S. W., Mahdy, A., Ghayd, I. M. & Aly, K. I. Bisbenzylidene cyclopentanone and cyclohexanone-functionalized polybenzoxazine nanocomposites: Synthesis, characterization, and use for corrosion protection on mild steel. Mater. Today Commun. 25, 101418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.101418 (2020).

Mohamed, M. G. & Kuo, S. W. Functional silica and carbon nanocomposites based on polybenzoxazines. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 220, 1800306. https://doi.org/10.1002/macp.201800306 (2019).

Ganjoo, R. et al. Experimental and theoretical study of Sodium Cocoyl Glycinate as corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in hydrochloric acid medium. J. Mol. Liq. 364, 119988. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie502578q (2022).

Yao, B. et al. Synthesis of sulfonic acid-containing polybenzoxazine for proton ex proton exchange membrane in direct methanol fuel cells. Macromolecules 47(3), 1039–1045. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma4020214 (2014).

Wan, S. et al. Soybean extract firstly used as a green corrosion inhibitor with high efficacy and yield for carbon steel in acidic medium. Ind. Crops Prod. 187(A), 115354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115354 (2022).

Nambiar, S., John, T. W. & Yeow, W. Polymer–composite materials for radiation protection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4(11), 5717–5726. https://doi.org/10.1021/am300783d (2012).

Tsutomu, T., Kawauchi, T. & Agag, T. High performance polybenzoxazines as a novel type of phenolic resin. Polym. J. 40(12), 1121–1131. https://doi.org/10.1295/polymj.PJ2008072 (2008).

Rajamanikam, R., Pichaimani, P., Kumar, M. & Muthukaruppan, A. Optical and thermomechanical behavior of benzoxazine functionalized ZnO reinforced poly benzoxazine nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 38(19), 1881–1889. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.23758 (2017).

Pardo, R., Zayat, M. & Levy, D. Thin film photochromic materials: Effect of the sol–gel ormosil matrix on the photochromic properties of naphthopyrans. ComptesRendusChimie 13(1), 212–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crci.2009.05.006 (2008).

Verker, R., Grossman, E. & Eliaz, N. Erosion of POSS-polyimide films under hypervelocity impact and atomic oxygen: The role of mechanical properties at elevated temperatures. Acta Mater. 57(4), 1112–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2008.10.054 (2009).

Jin, L., Agag, T. & Ishida, H. Bis (benzoxazine-maleimide) s as a novel class of high-performance resin: Synthesis and properties. Eur. Polym. J. 46(2), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2009.09.013 (2010).

Zhang, K. & Ishida, H. Thermally stable polybenzoxazines via ortho-norbornene functional benzoxazine monomers: Unique advantages in monomer synthesis, processing, and polymer properties. Polymer 66, 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2015.04.044 (2015).

Zhang, W. F., Lu, X., Xin, Z. & Zhou, C. L. A self-cleaning polybenzoxazine/TiO2 surface with superhydrophobicity and superoleophilicity for oil/water separation. Nanoscale 7(46), 19476–19483. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5nr06425b (2015).

Zhou, C. L., Lu, X., Xin, Z. & Liu, J. Corrosion resistance of novel silane-functional polybenzoxazine coating on steel. Corros. Sci. 70, 145–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2013.01.023 (2013).

Poorteman, M. et al. Thermal curing of paraphenylenediamine benzoxazine for barrier coating applications on 1050 aluminum alloys. Prog. Org. Coat. 97, 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2016.03.026 (2016).

Balanuca, B. et al. Phenolated oleic acid based polybenzoxazine derivatives as corrosion protection layers. ChemPlusChem 80(7), 1170–1177. https://doi.org/10.1002/cplu.201500092 (2015).

Jasim, A. S., Rashid, K. H., Al-Azawi, K. F. & Khadom, A. A. Synthesis of a novel pyrazole heterocyclic derivative as corrosion inhibitor for low-carbon steel in 1M HCl: Characterization, gravimetrical, electrochemical, mathematical, and quantum chemical investigations. Results Eng. 15, 100573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2022.100573 (2022).

Aly, K. I. et al. Conducting copolymers nanocomposite coatings with aggregation controlled luminescence and efficient corrosion inhibition properties. Prog. Org. Coat. 135, 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.06.001 (2019).

Agag, T., Geiger, S., Alhassan, S. M., Qutubuddin, S. & Ishida, H. Low-viscosity polyether-based main-chain benzoxazine polymers: Precursors for flexible thermosetting polymers. Macromolecules 43(17), 7122–7127. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma1014337 (2010).

Takeichi, T., Kano, T. & Agag, T. Synthesis and thermal cure of high molecular weight polybenzoxazine precursors and the properties of the thermosets. Polymer 46(26), 12172–12180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2005.10.088 (2005).

Liu, J., Agag, T. & Ishida, H. Main-chain benzoxazine oligomers a new approach for resin transfer moldable neat benzoxazines for high performance applications. Polymer 51(24), 5688–5694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2010.08.059 (2010).

Mehta, R. K., Gupta, S. K. & Yadav, M. Studies on pyrimidine derivative as green corrosion inhibitor in acidic environment: Electrochemical and computational approach. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10(5), 108499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2022.108499 (2022).

Saraswat, V. & Yadav, M. Improved corrosion resistant performance of mild steel under acid environment by novel carbon dots as green corrosion inhibitor. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 627, 127172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2021.127172 (2021).

Hegazy, M. A. A novel Schiff base-based cationic gemini surfactants: Synthesis and effect on corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in hydrochloric acid solution. Corros. Sci. 51, 2610–2618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2009.06.046 (2019).

Zhang, K., Liu, Y., Han, L., Wang, J. & Ishida, H. Synthesis and thermally induced structural transformation of phthalimide and nitrile-functionalized benzoxazine: Toward smart ortho-benzoxazine chemistry for low flammability thermosets. RSC Adv. 9, 1526–1535. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8RA10009H (2019).

El-Mahdy, A. F. M. & Kuo, S. W. Direct synthesis of poly (benzoxazine imide) from an ortho-benzoxazine: Its thermal conversion to highly cross-linked polybenzoxazole and blending with poly (4-vinylphenol). Polym. Chem. 9, 1815–1826. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8py00087e (2018).

Li, W.-H., He, Q., Zhang, S.-T., Pei, C.-L. & Hou, B.-R. Some new triazole derivatives as inhibitors for mild steel corrosion in acidic medium. J. Appl. Electrochem. 38, 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10800-007-9437-7 (2008).

El Din, A. S. & Paul, N. J. Oxide film thickening on some molybdenum-containing stainless steels used in desalination plants. Desalination 69(3), 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/0011-9164(88)80028-6 (1988).

Parveen, G. et al. Experimental and computational studies of imidazolium based ionic liquid 1-methyl-3-propylimidazolium iodide on mild steel corrosion in acidic solution. Mater. Res. Express 7, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ab5c6a (2019).

Davilal Parajuli, D. et al. Comparative study of corrosion inhibition efficacy of alkaloid extract of artemesia vulgaris and solanum tuberosum in mild steel samples in 1 M sulphuric acid. Electrochemistry 3(3), 416–433. https://doi.org/10.3390/electrochem3030029 (2022).

AbdEl-Lateef, H. M., Shalabi, K., Sayed, A. R., Gomha, S. M. & Bakir, E. M. The novel polythiadiazole polymer and its composite with a-Al(OH)3 as inhibitors for steel alloy corrosion in molar H2SO4: Experimental and computational evaluations. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 105, 238–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2021.09.022 (2022).

Sathiyanarayanan, S. & Balkrishnan, K. Prevention of corrosion of iron in acidic media using poly(o-methoxy aniline). Electrochem. Acta 39(6), 831–837. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4686(94)80032-4 (1994).

Muralidharan, S., Phani, K. L. N., Pitchumani, S., Ravichandran, S. & Lyer, S. V. K. Polyamino-benzoquinone polymers: A new class of corrosion inhibitors for mild steel. J. Electrochem. Soc. 142(5), 1478–1483. https://doi.org/10.1149/1.2048599 (1995).

Dubey, A. K. & Singh, G. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in sulphuric acid solution by using polyethylene glycol methyl ether (PEGME). Port. Electrochim. Acta 25, 221–235. https://doi.org/10.4152/pea.200702221 (2007).

Mwakalesi, A. J. Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in sulphuric acid solution with tetradenia riparia leaves aqueous extract: Kinetics and thermodynamics. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 13(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.33263/BRIAC131.032 (2023).

Gholami, M., Danaee, I., Maddahy, M. H. & Rashvandavei, M. Correlated ab initio and electroanalytical study on inhibition behavior of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole and its thiole−thione tautomerism effect for the corrosion of steel (API 5L X52) in sulphuric acid solution. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 14875–14889. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie402108g (2013).

Tanwer, S. & Shukla, S. K. Cefuroxime: A potential corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in sulphuric acid medium. Prog. Color Colorants Coat. 16, 125–138. https://doi.org/10.30509/pccc.2022.166974.1165 (2023).

Arukalam, I. O., Madufor, I. C., Ogbobe, O. & Oguzie, E. E. Inhibition of mild steel corrosion in sulphuric acid medium by hydroxyethyl cellulose. Chem. Eng. Commun. 202(1), 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986445.2013.838158 (2014).

Umoren, S. A. & Obot, I. B. Polyvinyl pyrrolidone and polyacrylamide as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic medium. Surf. Rev. Lett. 15(3), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218625X08011366 (2008).

Alamry, K. A., Hussein, M. A., Musa, A., Haruna, K. & Saleh, T. A. The inhibition performance of a novel benzenesulfonamide-based benzoxazine compound in the corrosion of X60 carbon steel in an acidizing environment. R. Soc. Chem. Adv. 11(12), 7078–7095. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0RA10317A (2021).

Umoren, S. A., Ebenso, E., Okafor, P. C. & Ogbobe, O. Water-soluble polymers as corrosion inhibitors. Pigment Resin Technol. 35(6), 346–352. https://doi.org/10.1108/03699420610711353 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Academy of Science Research & Technology (ASRT) in Egypt as part of the research Project (RESPECT_1 ID: 10019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.M.S.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, supervision, visualization, writing—reviewed editing. K.I.A.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, supervision, visualization, writing—review and project administration, and funding acquisition. M.G.M.: data curation, writing original draft, supervision, and writing—review and editing. A.A.A.: methodology, investigation, data curation, visualization, and editing. M.R.B.: data curation, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. M.A.H.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, resources, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soliman, A.M.M., Aly, K.I., Mohamed, M.G. et al. Synthesis, characterization and protective efficiency of novel polybenzoxazine precursor as an anticorrosive coating for mild steel. Sci Rep 13, 5581 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30364-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30364-x

This article is cited by

-

Nonylphenol-based polybenzoxazine composites: hydrophobic coating, ultra-low-k and anticorrosion applications

Journal of Materials Science (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.