Abstract

Empathy enables us to understand the emotions of others and is an important determinant of prosocial behavior. Investigating the relationship between mindfulness and empathy could therefore provide important insights into factors that promote interpersonal understanding and pathways that contribute to prosocial behavior. As prior studies have yielded only inconsistent results, this study extended previous findings and investigated for the first time the associations of two important factors of mindfulness (Self-regulated Attention [SRA] and Orientation to Experience [OTE]) with two commonly proposed components of empathy (cognitive empathy and affective empathy). Using a community sample of N = 552 German-speaking adults, the two mindfulness factors were differentially associated with cognitive and affective empathy. SRA correlated positively with cognitive empathy (r = 0.44; OTE: r = 0.09), but OTE correlated negatively with affective empathy (r = − 0.27; SRA: r = 0.11). This negative association was strongest for one specific aspect of affective empathy, emotional contagion. Revisiting previously reported mediating effects of emotion regulation, we found that emotional awareness mediated the associations with both components of empathy, but only for SRA. Together, these findings imply that mindfulness benefits the cognitive understanding of others’ emotions via two distinct pathways: by promoting emotional awareness (SRA) and by limiting the undue impact of others’ emotions on oneself (OTE).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mindfulness is a concept with roots in ancient Buddhist meditation traditions1,2 and in the last decades has become a major topic in psychology3, with numerous studies reporting beneficial outcomes of mindfulness on clinical4, cognitive5, and prosocial processes6. A common definition describes mindfulness as intentionally maintaining attention on the present moment while adopting a nonjudgmental stance1. In a functional analytic way, the form of contact with the present moment in mindfulness can further be described as defused, accepting, and open, with a person noticing the experiences in the present moment, but with a transcendent sense of self7. Bishop and colleagues emphasized the dimensionality of the construct and proposed two components3: Self-regulated Attention (SRA; the ability to bring one’s attention to the present moment and to intentionally switch attention between objects) and Orientation to Experience (OTE; an open, accepting, curious, and nonjudgmental attitude towards own experiences and the world). This definition may prove particularly useful, as the two components likely also relate to two important meditation styles8. Focused Attention meditation involves selectively maintaining and effortfully bringing back one’s moment-to-moment attention to a selected object, and this style appears to be associated with the cultivation of SRA8,9. Another meditation style, Open Monitoring meditation, involves non-reactive, effortless monitoring of one’s moment-to-moment experience, without explicitly selecting and maintaining focus on a particular object. This style appears to be associated with the cultivation of OTE8,9. This link between the two components of mindfulness and specific meditation styles could allow tailor-made interventions (training with a focus on one meditation style) that could have the potential to not only promote the associated mindfulness-component, but possibly also other related outcomes.

Empathy can be defined as a skill or trait that enables individuals to vicariously experience and understand the emotions of others10,11. There are many different definitions and conceptualizations regarding the structure of empathy12. One common definition suggests two interrelated components: Affective empathy describes the ability to vicariously experience others’ emotions, whereas cognitive empathy describes the processes that enable one to understand and interpret one’s own and others’ emotions10,11. Other definitions proposed emotion regulation13 or prosocial motivation14 as a third additional component, two concepts that are considered as strongly related to, but that are deliberately separated from empathy in the two-component model11. In general, empathy is viewed as a determinant of prosocial behavior and may enable us to respond appropriately to the needs of others or may motivate us to help, which could benefit our social relationships14,15.

Associations between mindfulness and empathy could provide important insights into factors underlying or promoting prosocial behavior and thus warrant further investigation. However, research on both mindfulness and empathy is surrounded by methodological and conceptual issues, which may give rise to inconsistent results12,16. This is also reflected in the extant literature on their mutual relationship.

Prior studies reported positive associations of mindfulness with components of cognitive empathy17,18,19,20, but the association of mindfulness with components of affective empathy varied widely, from positive17,21, null18, to negative19,20. A recent meta-analysis of studies on the relationship between mindfulness and empathy (as measured with the Interpersonal Reactivity Index22; IRI) in samples of counseling professionals reported an overall positive association of mindfulness with perspective taking, and a negative association with personal distress23. However, in many of these studies, either mindfulness, empathy, or both constructs were measured with unidimensional scales, even though definitions and empirical findings indicate multidimensionality9,11. More recent studies investigated the associations of mindfulness and empathy also on their subscale levels. Yet, associations still await their contextualization into the two-component models of mindfulness and empathy.

MacDonald and Price24 reported medium-to-high correlations between the subscales of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)25 with cognitive and affective empathy, as measured with the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE)11. The FFMQ measures mindfulness with five facets (i.e., subscales): Observe (actively perceiving internal and external stimuli), Describe (the ability and tendency to describe internal experiences with words), Actaware (being attentive towards one’s own actions), Nonjudge (taking a neutral, non-judgmental stance towards one’ own thoughts and feelings), and Nonreact (attending to feelings and thoughts without being carried away by them). Observe, Describe, and Nonreact correlated positively with cognitive empathy, and Describe, Nonreact, Actaware, and Nonjudge correlated negatively with affective empathy. These correlations were partially mediated by alexithymia (i.e., difficulties in recognizing, labeling, and processing emotions), highlighting the importance of emotional awareness for empathic processes.

Fuochi and Voci26 investigated associations between the subscales of the FFMQ and the IRI. All five facets of mindfulness correlated positively with perspective taking. Observe, Describe, and Actaware correlated positively with the subscale emotional concern, a result that is partially in line with a previous study that reported a positive association between the facets Observe and Describe and emotional concern27, and all facets except Observe correlated negatively with personal distress. Further, they expanded the extant findings on specific mediational paths. They reported an indirect effect of mindfulness on empathy via emotion regulation processes as measured with the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS)28. While emotional awareness (the tendency to be aware of, acknowledge, and attend to emotions) mediated the associations of Observe, Describe, and Nonreact with the components of empathy, impulse control (the tendency to remain in control of one’s behavior when experiencing negative emotions) and emotion regulation strategies (the belief of being able to effectively regulate emotions when one is upset) mediated the respective associations with Actaware, Nonjudge, and Nonreact. Such associations between mindfulness, empathy and emotion regulation abilities are also in line with studies reporting a positive relationship between self-reported mindfulness and trait emotional intelligence (TEI)29,30, i.e., emotion-related behavioral dispositions and self-perceptions, including but also going beyond concepts such as trait-empathy and self-perceived emotion regulation abilities31.

Still, even these studies are subject to some further methodological limitations. First, extant research considered no or only a limited number of potential background confounders. Meditation experience was reported to moderate the associations of mindfulness with other constructs, including empathy26,32. Additionally, there also are sex differences in empathy33,34. However, when investigating indirect effects, only MacDonald and Price24 controlled for sex differences and neither study considered participants’ meditation experience.

Adding to this, across many studies17,18,19,21,24,26, only limited emphasis was put on delineating empathy from related concepts. This remains an important research desiderate, especially regarding emotional contagion. In empathy, the source of the emotion is recognized to lie outside rather than within the self (referred to as self/other distinction)15. While emotional contagion surely contributes to the empathic process, a high tendency to “catch” the emotions of others could be grounded in a limited ability to differentiate between the self and others, thus making it partly different from empathy15. Accordingly, high levels of emotional contagion have even been associated with negative outcomes, such as impaired emotion regulation, neuroticism, abnormal eating behavior and general psychological vulnerability33,35,36. High emotional contagion appears to be especially harmful in emotionally negative contexts, as individuals could become overwhelmed by the emotions of others, resulting in emotional distress37. Psychological benefits of empathy might thus specifically depend on the absence of high levels of emotional contagion. Negative associations between self-reported mindfulness and emotional distress, a potential outcome of high emotional contagion, were reported as well23,30, and a lower susceptibility to emotional contagion was proposed as a potential pathway between mindfulness, less anxiety symptoms, and a lower risk for burnout in health care professionals38,39. Therefore, one could expect negative associations of mindfulness specifically with emotional contagion, which could also have some relevance as a link between mindfulness and beneficial mental health outcomes4,38.

Other, more general limitations were mainly related to the applied self-report measures. Most studies either assessed mindfulness using the Mindfulness Awareness Attention Scale (MAAS)40 or the FFMQ. While both measures demonstrate good psychometric properties40,41, the MAAS has been criticized for being partially inconsistent with mindfulness definitions. Its items capture a unidimensional construct of mindlessness (emphasis ours): It therefore appears to reflect more strongly a (negative) element of mindfulness related to absent-mindedness, compared to other measures that may capture a broader subset of (positive) aspects of mindfulness25,42. The FFMQ on the other hand provides a more comprehensive picture of the construct. The five-facetted structure derives from empirical findings25,41, which also poses some challenges in linking it to (other) theoretical assumptions about, or definitions of, mindfulness (e.g., the two-component model3). Advantageously, the facets of the FFMQ have also been shown to fit well with a two-factor higher-order structure associated with SRA and OTE9, combining its empirical strengths with the advantages of the two-component model3. The factorial validity of these two higher-order factors was recently replicated, and differential associations of the two factors with mental health outcomes in meditating and nonmeditating samples were suggested32,43. Extracting two higher-order factors from the FFMQ facets could thus offer an efficient, empirically, as well as theoretically supported operationalization of mindfulness. This approach remains yet to be applied when investigating associations with empathy and may provide information on the specific pathways along which mindfulness is associated with it.

The most commonly applied self-report measure to assess empathy was the IRI. However, the subscales of the IRI were criticized to possibly confound empathy with other constructs, such as imagination and emotional self-control11,37,44. In contrast, the QCAE is a well-established self-report instrument of empathy, but has so far only rarely been used in the context of mindfulness research20,24. The QCAE delineates empathy better than the IRI from reactive emotions, such as sympathy, and its structure is in line with up-to-date definitions of two higher-order factors, each of which is measured with multiple subscales. This allows for both precise and general statements about the associations of other constructs with the components of empathy11,33,45, specifically emotional contagion. However, the associations of the subscales of affective empathy (i.e., Emotion Contagion, Proximal Responsivity, and Peripheral Responsivity; see “Methods”) with mindfulness have not yet been investigated.

In summary, recent large-scale studies have suggested several links and pathways between mindfulness and empathy24,26. Still, the relationship between mindfulness and empathy is far from being clear and due to methodological and conceptual limitations their relationship requires further research. To provide insight both on a theoretical and empirical level, investigations should be guided by theoretical conceptualizations of the two constructs, such as the two-component model of mindfulness, but also probe associations between sub-components that could explain heterogeneity in previous results, such as with emotional contagion. Other methodological aspects, such as considering different background confounders, need further attention as well. In addition, reported mediating effects of emotion regulation abilities between mindfulness and empathy could be fruitfully re-investigated in a study that aims to account for these previous limitations. Together, this could provide much needed clarity on the interrelation of mindfulness and empathy and pave the way forward for future research or interventional approaches. This motivated the present research.

The present research

Our first research goal aimed at replicating the higher-order two-factor structure for the FFMQ9,32,43, in order to operationalize mindfulness in line with the two-component model3. Following a replication-extension approach46, the second research goal aimed at extending previous findings by investigating the associations of these two higher-order factors of mindfulness with components of empathy in detail.

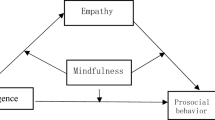

We thus had several hypotheses for the present study (for a summary visualization set of hypotheses, see Fig. 1): We expected that SRA will correlate positively with cognitive empathy (Hypothesis 1) and affective empathy (i.e., QCAE subscales Peripheral and Proximal Responsivity), but not with emotional contagion (QCAE subscale Emotion Contagion; Hypothesis 2). We further expected that OTE will correlate positively with cognitive empathy (Hypothesis 3), but negatively with affective empathy, especially with its sub-component emotional contagion (Hypothesis 4).

As the third research goal, we aimed to conceptually replicate mediational effects of emotion regulation abilities between mindfulness and empathy, as previously reported by Fuochi and Vochi26. We expected that the relationships between SRA and cognitive and affective empathy will be mediated by the DERS subscale Emotional Awareness (Hypothesis 5) and that the relationships between OTE and cognitive and affective empathy will be mediated by the DERS subscales Impulse Control and Emotion Regulation Strategies (Hypothesis 6).

Further, we controlled for the possible confounders participant sex and meditation experience. In an exploratory analysis, we additionally investigated the effects segmented by sex, and in a supplemental analysis, for better comparability with previous studies, we investigated the mediational effects also on the facet level of mindfulness.

Methods

Participants

The sample for this study consisted of a total of N = 552 German-speaking participants from the general adult population (67% women; age: M = 31.8, SD = 14.2, range: 18–78 yrs.). 34% of participants reported meditating at least once a week and thus could be considered regular meditators41. Further sample characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Procedure

Participants were recruited by several study inviters via social media and personal contacts to partake in an online survey created with SoSci Survey47 that consisted of 13 scales in total (as assembled for a larger research project), five of which were relevant for the present study. An overview over all scales administered, as well as their respective position within the survey, is provided online (see “Open practices” section, below).

Data collection took place during April 2021. Participants had to be at least 18 years old, proficient in the German language, and provided informed consent before inclusion in the study. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. As an incentive, participants could opt-in to partake in a raffle with the possibility of winning one of two 25€ coupons. Contact information (email addresses) was electronically stored separately from all other participant data to guarantee anonymity and irrecoverably deleted after the raffle closed.

In total, N = 850 persons accessed the online survey, of which n = 558 filled out all five scales that were relevant for this study. Three cases had to be excluded as they stated being younger than the required age limit; two more cases were excluded for more than 5% missing items in at least one of the relevant scales; one case had to be excluded as, judging from the time count provided by the online survey, the participant had merely rushed through the survey, indiscriminately selecting the same response alternative for most items. Six individual missing values in the remaining data were replaced by the respective individual scale means.

We utilized the safeguard power-analytic approach to perform a conservative (i.e., realistic, if not “calculated pessimistic”) a priori power analysis48, using G*Power49. Following this approach, we did not select empirically observed effect sizes as the target effect size for this study, but rather (in the manner of reasonable calculated pessimism) the lower bound of the 60% confidence interval (r = 0.13) of the most conservative estimate of the association between mindfulness and empathy available from prior related research24,26 (namely, r = 0.16). This power analysis (two-tailed α = 0.05; desired power 1 – β = 0.80) suggested a sample size of at least N = 462 necessary for an effect of this size. A sample size of N = 462 was also found to achieve a power of 0.80 in a mediation analysis, using a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure for relevant small-to-medium effects (i.e., standardized estimates = 0.14)50. This study’s sample size thus was deemed appropriate to detect target effects of relevant size.

Measures

All scales were presented in German. Sample reliabilities internal consistency were calculated according to McDonald’s ω and Cronbach’s α, using the MBESS package in R51, and are reported in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire

Mindfulness was measured with a 23-item short form32 of the 39-item Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire25. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never or very rarely true to 5 = very often or always true. Four items each measured the facets Observe (e.g., “I pay attention to sensations, such as the wind in my hair or sun on my face”), Describe (e.g., “I’m good at finding words to describe my feelings”), Actaware (e.g., “I am easily distracted”; reverse-scored), and Nonjudge (e.g., “I tell myself I shouldn’t be feeling the way I’m feeling”; reverse-scored); Nonreact was measured with all seven items of the full form (e.g., “In difficult situations, I can pause without immediately reacting”). The FFMQ demonstrated high construct validity in different samples41, and the German short form showed improved psychometric properties relative to the full form9.

Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy

Empathy was measured with the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy11. The QCAE has a total of 31 items, which are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. It assesses the two dimensions of cognitive and affective empathy on five subscales: Perspective Taking (the ability to intuitively put oneself in situations of others and interpret these from their perspective; with items such as “I can pick up quickly if someone says one thing but means another”), Online Simulation (attempting to put oneself in another person’s position to understand their feelings and anticipate future actions; with items such as “I find it easy to put myself in somebody else’s shoes”), Emotion Contagion (automatically mirroring other people’s emotions; with items such as “People I am with have a strong influence on my mood”), Proximal Responsivity (the affective responsivity when other people’s feelings are observed in a close social context; with items such as “I often get emotionally involved with my friends’ problems”), and Peripheral Responsivity (the affective responsivity when other people’s feelings are observed in a more detached context, like observing characters in a movie; with items such as “I usually stay emotionally detached when watching a film”, reverse-scored). The first two subscales measure cognitive empathy, and the latter three subscales measure affective empathy. The QCAE demonstrated good psychometric properties with good convergent and construct validity11. High validity and reliability were also replicated in the German translation of the QCAE45.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale

Aspects of emotion regulation were measured using three of the six subscales of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale28: Lack of Emotional Awareness (six items; e.g., “I pay attention to how I feel”, reverse-scored), Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies (eight items; e.g., “When I’m upset, it takes me a long time to feel better”), and Impulse Control Difficulties (six items; e.g., “When I’m upset, I become out of control”). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = almost never to 5 = almost always. The DERS has shown to be valid across non-clinical and clinical populations also in the German translation52. High DERS scores reflect difficulties in emotion regulation. In this study, DERS subscales were reverse-scored to allow for an easier interpretation and to thereby reflect emotion regulation abilities (i.e., emotional awareness, emotion regulation strategies, and impulse control). This framed the subscales of the DERS as abilities or skills, which much better fitted the skill-related conceptualization of mindfulness in the FFMQ.

Meditation experience

Following a slightly adapted approach as in a previous study32, the practice of (1) meditation, (2) autogenic training or progressive muscle relaxation, or (3) other relaxation techniques was measured with three items (e.g., “How often do you practice meditation?”). Items were rated on 7-point scales (1 = never, 2 = not regularly, 3 = at least once per month, 4 = once per week, 5 = twice per week, 6 = three times per week, 7 = four times per week and more). For each participant, the highest reported value across the three items was transferred to a new variable capturing overall meditation experience (ranging from 1 = never/not regularly, 2 = at least once a month, 3 = once per week, 4 = twice per week, 5 = three times per week, 6 = four times per week and more). During this step, we combined the response options 1 = never and 2 = not regularly into one option (1 = never/not regularly) to ensure maximum comparability with the scale used in the previous study (associations with meditation experience on the 6-point and 7-point scales were, however, identical). Participants who reported doing some form of meditation practice were queried on the length of their meditation practice, on the time in years since they started practicing, and on the type of practice they did most in the last 6 months.

Data analysis

The data were examined for missing values, scale score distributions, scale reliabilities, and fit of the data to the assumptions of the utilized data-analytic approach. Some score distributions were moderately skewed. Yet, due to otherwise mostly close approximations of scores to the normal distribution, the large sample size, and thus the applicability of the central limit theorem, and the similarity of results with non-parametric methods, parametric methods were used throughout for analysis. Significance was set to p < 0.05 (two-sided).

Open practices

We disclose how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures in the study53. All data, materials (variable descriptions, instructions, demographic items), and the entire analysis code are available at https://osf.io/ujp3e.

Structural analysis

As in previous studies9,32,43, the two-factor higher-order model was investigated with exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM)54, fitting a two-factor model on the scale scores of the five facets of the FFMQ. ESEM is an integration and combination of the benefits of both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, as it allows for cross-loadings but also provides additional fit indices54. This approach provided insight into the factorial structure of the present data and provided sample-specific factor scores, which were used for further analysis. Analyses were conducted with the lavaan and psych packages in R55,56. Robust maximum-likelihood estimation (MLR) was used, as well as oblique geomin rotation. This latter method provides unbiased results, akin to confirmatory factor analysis and target-rotated solutions, without the need to specify a factor-loading pattern57, and, in addition, incorporates a complexity parameter which increases with the number of factors, in order to avoid inflated factor intercorrelations54.

The sample’s adequacy for factor analysis was checked with the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test and Bartlett’s sphericity test. Model fit was assessed with the comparative fit index (CFI; good fit: ≥ 0.95), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; good fit: ≥ 0.95), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; good fit: < 0.06), and the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR; good fit: < 0.08). Benchmarks were taken from Hu and Bentler58.

Correlation and mediation analysis

Correlation and mediation analysis was conducted with the psych and lavaan packages in R. We calculated Pearson’s r and Spearman’s rs for all variable pairs. As values were very similar, only Pearson r values are reported. Results were interpreted according to the cutoffs proposed by Funder and Ozer59: r = 0.05 indicated a very small, r = 0.10 a small, r = 0.20 a medium, r = 0.30 a large, and r ≥ 0.40 a very large effect.

Mediation analyses examined all three DERS subscales (measuring emotional awareness, impulse control, and emotion regulation strategies) in parallel, testing for mediating effects for the associations between SRA and OTE (predictors), and cognitive and affective empathy (outcomes). In additional, mediation analysis was also performed using the five facets of mindfulness as predictors. Participant sex (using a dummy variable for this analysis step, coded 0 = female and 1 = male) and meditation experience were included as control variables. Additionally, in an exploratory analysis, multigroup structural equation modeling was used to investigate direct and indirect effects segmented by participant sex. Confidence intervals (CIs) of all effect estimates were obtained, using a 95% bias-corrected bootstrapping approach with 10,000 samples60. Statistical significance was determined using the 95% bias-corrected bootstrapping CIs, and standardized estimates were used to evaluate the size of the effects.

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in this study adhere to the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards, and with institutional guidelines of the School of Psychology, University of Vienna. Study participation did not affect the physical or psychological integrity, the right for privacy, or other personal rights or interests of the participants. Such being the case, according to national laws (Austrian Universities Act 2002)61, this study was exempt from formal ethical approval.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Results

Means, standard deviations, intercorrelations for all study variables, and measures of reliability for the scale scores, are provided in Table S1 in Supplemental Materials.

Two-factor higher-order structure of mindfulness

Both the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test (KMO = 0.62) and Bartlett’s sphericity test (χ2[10] = 286.58, p < 0.001) indicated that the FFMQ data were appropriate for factor analysis. The ESEM had a good fit, χ2(1) = 0.38, p = 0.54, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, SRMR = 0.005, RMSEA = 0.000, 90% CI = [0.000, 0.087], indicating a two-factor higher-order structure similar to the one reported in previous studies9,32,43. Factor loadings are reported in Fig. S1 in Supplemental Materials. Observe and Describe loaded high on SRA, and Actaware and Nonjudge high on OTE. Nonreact loaded on both factors, but higher on OTE. The two higher-order factors had an intercorrelation of r = 0.23 which is comparable to previous studies with (mostly) nonmeditating samples9,32.

Associations between mindfulness and empathy

There were two distinct patterns in the associations between the two higher-order factors of mindfulness and empathy (Table S1). SRA had a very large positive correlation with cognitive empathy (r = 0.44) and a small positive correlation with affective empathy (r = 0.11). On the subscale level, the second correlation was driven by Peripheral Responsivity and Proximal Responsivity; the association with Emotion Contagion was weaker and directionally reversed (Table S1). In contrast, OTE only had a small positive correlation with cognitive empathy (r = 0.09), but a medium to large negative correlation (r = -0.27) with affective empathy, which, on the subscale level, was driven by Emotion Contagion (larger association, compared to Peripheral Responsivity and Proximal Responsivity; Table S1).

Mediation analysis

Higher-order factor level

Controlling for participant sex and meditation experience, the total effects of SRA to cognitive and affective empathy were r = 0.43, 95% CI = [0.35, 0.52], and r = 0.17, 95% CI = [0.08, 0.25]; and of OTE to cognitive and affective empathy r = − 0.06, 95% CI = [− 0.14, 0.04], and r = − 0.31, 95% CI = [− 0.39; − 0.22]; i.e., there was no significant total effect of OTE on cognitive empathy anymore. Meditation experience had a direct effect to SRA (r = 0.10, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.15]) but no other variable, whereas participant sex had a direct effect to all variables except emotion regulation strategies (for a display of all confounder effects, see Fig. 2 and Table S3).

Associations between two higher-order-factors of mindfulness, emotional awareness, and cognitive and affective empathy. SRA = Self-regulated Attention, OTE = Orientation to Experience. Numbers are standardized path coefficients. Only significant direct and indirect paths (p < 0.05; see Table 2) and confounding effects of meditation experience and participants’ sex (see Table S3) are displayed. Significance was determined via 95% bias-corrected bootstrapping.

Mediation analysis (Table 2 and Fig. 2) indicated that emotional awareness, but neither impulse control nor emotion regulation strategies, mediated these associations significantly. Indirect effects of emotional awareness were largest for the associations of SRA with cognitive and affective empathy, but smaller, and thus evidently less relevant, for the associations of OTE with cognitive and affective empathy.

SRA was positively associated with cognitive empathy both directly and indirectly (partial mediation), whereas with affective empathy mostly indirectly (full mediation; no significant direct effect, see Table 2 and Fig. 2). For OTE, there were tiny indirect effects, which contributed to its negative total effects on cognitive and affective empathy (Table 2).

Facet level

Total, direct, indirect and confounding effects obtained in the facet-level analyses are displayed in supplementary materials (Table S2; Fig. S2). There were positive total effects of Observe and Describe on cognitive and affective empathy. Actaware had a negative total effect on affective empathy and Nonreact a positive total effect on cognitive empathy, and a negative total effect on cognitive empathy. Again, only emotional awareness contributed significantly to these total effects. The largest indirect effect concerned the association of Describe with cognitive empathy (which also had the largest total effect overall), which was partially mediated via emotional awareness. The indirect effects of the associations of Observe with cognitive empathy, and of Describe with affective empathy, appeared of further relevant size. The former association was partially, and the latter association fully, mediated via emotional awareness. The remaining indirect effects were only tiny and appeared, hence, less relevant overall.

Multigroup analysis

In an exploratory analysis, the total, direct and indirect effects between the two higher-order factors of mindfulness and empathy were investigated segmented by sex (displayed in supplementary materials, Tables S4 and S5). Effects were similar to those across groups (see Table 2). The direct effect of SRA to cognitive empathy and its indirect effect via emotional awareness appeared to be slightly stronger in female participants, and in contrast, the direct effect of OTE to affective empathy appeared to be slightly stronger in male participants. Indirect effects between OTE and cognitive and affective empathy were tiny and statistically non-significant in analyses segmented by participant sex.

Discussion

This study revisited—along with important extensions that went beyond prior related research evidence—the correspondence of self-reported mindfulness with empathy. We delineated two empirically-derived higher-order factors of mindfulness and, in extension to existing studies, investigated their differential associations with cognitive and affective empathy. We obtained evidence of distinct patterns of association between mindfulness and empathy, with Self-regulated Attention (SRA) being strongly related to cognitive empathy and moderately related to affective empathy. On the other hand, Orientation to Experience (OTE) had a small positive relationship with cognitive empathy, but a negative relationship with affective empathy. Further analyses on the subscale level indicated that negative associations with affective empathy mainly concerned emotional contagion. Lastly, we aimed at replicating previously reported mediational effects of emotional awareness, impulse control and emotion regulation strategies between mindfulness and empathy26. In the present study, only emotional awareness, but neither impulse control nor emotion regulation strategies, mediated the associations between mindfulness and empathy. Indirect effects were of a relevant size for SRA, but were less relevant for OTE.

ESEM indicated a good fit of two-higher order factors on the FFMQ data, thus replicating previous findings32,34,43. These results provide further evidence that the extraction of two higher-order factors leads to an efficient, empirically as well as theoretically supported, operationalization of mindfulness. Observe and Describe loaded high on SRA, and Actaware and Nonjudge on OTE. Nonreact loaded on both factors, but higher on OTE. Factor structure differences between non-meditators and meditators have been discussed in previous studies: The present study used a mixed sample (34% meditators) and was most comparable to the sample in a study of Burzler and collegues32. The ranking of factor loadings was largely similar in this previous study and in the present study. A single deviation occurred for Describe, which loaded only on SRA in the present study, but not on OTE, a pattern which has otherwise been reported for meditating samples43.

In the correlation analysis, the two higher-order factors of mindfulness showed specific associations with the two components of empathy. SRA correlated positively with cognitive empathy (Hypothesis 1) and to a lesser extent also with affective empathy, but not with emotional contagion (Hypothesis 2). Thus, SRA apparently was specifically associated with a heightened understanding of one’s own and others’ emotions in an interpersonal context, or in other words, the attentional component of mindfulness seemed to be primarily associated with cognitive aspects of empathy. It is thus possible that cognitive empathy could benefit from heightened mindful attention. Even though our cross-sectional design does not allow claims on such potential causal effects, these findings may provide inspiration for future research, and interventions specifically targeting the cultivation of SRA (as does Focused Attention meditation) could enhance interpersonal understanding.

OTE had a small positive correlation with cognitive empathy (Hypothesis 3), but a large negative correlation with affective empathy, primarily driven by emotion contagion (Hypothesis 4). High emotional contagion may be a psychological risk factor for neuroticism, alexithymia, and depression33,36, and associations of emotion contagion with further pathological conditions have been reported as well35,37. OTE thus appeared to be the main protective factor, relative to SRA, of potentially problematic aspects in the empathic process associated with emotion contagion. This finding is further backed by previous evidence of strong associations of OTE with positive mental health outcomes43.

These implications could also be linked to previous research on trait emotional intelligence (TEI; i.e., emotion-related dispositions and self-perceptions31). TEI was associated with lower emotional distress, positive mental health outcomes, and with mindfulness, respectively29,30. Further, mindfulness interventions seemed to promote TEI alongside subjective well-being62. Given the common associations, OTE may be the component of mindfulness that is specifically associated with higher TEI. In turn, TEI could also be associated with lower susceptibility to emotional contagion in the context of its role as a protective factor against emotional distress or burnout30,63, ultimately having a positive impact on mental health. Future research is needed to examine differential associations of the two components of mindfulness with TEI, as well as the role of emotional contagion in linking OTE to mental health outcomes, as these associations may be of clinical importance.

Interventions based on Open Monitoring meditation (which specifically benefits the cultivation of OTE) could thus protect from, or improve, symptoms in individuals with increased risk of, and susceptibility to, taking over others’ (negative) emotions. This could be of particular interest for groups frequently exposed to emotionally stressful situations (e.g., occupationally, such as counselors, social workers and health workers in general38,64; or in some patient populations35). Future studies should thus investigate the effects in such groups, as the potential benefits of mindfulness on empathy may vary among different populations. Effects could also be limited in individuals with low levels of affective empathy, such as individuals high in socially aversive personality traits65 (i.e., the dark triad of personality: narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism66). To some degree, these individuals might also be protected from psychological risks associated with a high susceptibility to emotional contagion33, but an extremely low level of affective empathy could completely hinder the empathic process15, resulting in empathic dysfunction65. Longitudinal studies are thus needed to clarify these relationships: Previous results of mindfulness-based interventions on trait empathy were mixed (e.g., a meta-analysis that indicated no effects in counselors23, and conversely reviews on effects in other healthcare professionals seemed more promising39,67). However, taking our cross-sectional results into account, a particular emphasis on tailor-made mindfulness-interventions and multidimensional outcome measures could result in more robust findings and potentially uncover specific pathways in interventional studies as well. Further, as changes in traits regarding emotional tendencies might manifest only after longer time periods68, follow-up measurements and studies applying particularly long mindfulness-programs might be needed.

In summary, the correlational findings were in line with Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the present study. The positive association with cognitive empathy and the negative association with emotional contagion across the two mindfulness components highlights the potential of mindfulness-based interventions to improve interpersonal understanding, without introducing a higher susceptibility to emotional contagion, thereby ultimately benefitting psychological health.

Emotional awareness was confirmed as an important mediator of the association between mindfulness and empathy. This is consistent with what has been previously reported in recent large-scale studies24,26. Mediational effects of emotional awareness seemed to depend on the specific higher-order factor of mindfulness: SRA (and its corresponding main subscales, i.e., Observe and Describe) were positively related with cognitive and affective empathy via emotional awareness (Hypothesis 5). Against our expectations, there were also significant indirect effects between OTE (and its corresponding main subscales, i.e., Actaware and Nonreact) and both empathy dimensions via emotional awareness, which, in contrast to SRA, were negative. However, these indirect effects for OTE were tiny and thus of small relevance. For Nonjudge, which also loaded high on OTE, no indirect effects were observed at all.

No indirect effects of impulse control or emotion regulation strategies (cf. Fuochi and Voci26) were observed for the associations between the two-higher order factors or the five facets of mindfulness and cognitive and affective empathy (Hypothesis 6). These null findings could stem from using a measure in the present study that better delineates empathy from related concepts and that is based on more up-to-date definitions of empathy (i.e., the QCAE) rather than the IRI, which has often been used in previous studies26. The IRI was based on a broad definition of empathy11 and may rather capture empathy-related constructs, such as emotional self-control or imagination11,44. This might also explain why the IRI and its scales were more strongly related to emotion regulation processes in previous studies. Furthermore, the present study controlled for additional background confounders (meditation experience and sex).

Interestingly, meditation experience only had a small direct effect on SRA, and no effect on OTE in the present study. In contrast, previous studies indicated medium effects on both SRA and OTE32, and increased trait mindfulness after mindfulness practice in general69. Yoga was by far the most common meditation technique in the present sample. Previous research indicated no large differences in trait mindfulness between different meditation techniques70. However, the relationship between meditation experience and trait mindfulness could depend more strongly on the duration of sessions or years of practice71 than session frequency. Differential associations of meditation experience and the two-higher order factors of mindfulness should be further investigated in future research.

Participants’ sex had direct effects to SRA, OTE, and cognitive and affective empathy, indicating higher scores in woman in all variables except OTE. In line with previous findings33, this effect was strongest for affective empathy. Associations were also investigated segmented by participant sex in an exploratory multigroup analysis, and the overall pattern of results was similar within groups compared to the results across groups.

Considering the overall weaker indirect effects explaining the associations of OTE with empathy, future studies should investigate further possible mediators in addition to those re-investigated in the current study. For example, Fuochi and Voci also reported positive indirect effects of nonattachment (a flexible way of dealing with one’s experiences and concepts of the world without clinging to them), decentering (the ability to gain a distanced perspective on one’s thoughts, to step outside one’s own perspective) and non-rumination (not showing repetitive, negative, and self-centered thoughts about the past or the future) for the associations of mindfulness facets mainly contributing to OTE and empathy26. Future studies on these (and other) mediators could provide additional information on differential associations of the two higher-order factors of mindfulness and empathy.

Our findings are broadly compatible with the tenets of monitoring and acceptance theory (MAT)72, which considers acceptance (which is comparable to OTE in the present study) a broad emotion regulation skill that is responsible for the beneficial effects of mindfulness on mental health. On the other hand, attention monitoring (which is comparable to SRA) is considered to improve selective and executive attention in affectively neutral contexts and the awareness of affective information in affective contexts (Tenet 1 and 1a of MAT); only coupled with acceptance it may also allow the efficient processing of emotional information. Otherwise, attention monitoring may exacerbate negative thoughts, feelings, or symptoms, according to MAT (Tenet 1b). The high positive association of SRA with cognitive empathy in the present study corroborates the assumption that attention monitoring improves the awareness of affective information. However, our results also suggest that there might be pathways of attention monitoring for the effective processing of emotional information specifically in empathic processes that are independent of acceptance and depend on the awareness of one’s own emotions only. Thus, our findings challenge Tenet 1b of MAT. This should be investigated in more detail in future studies.

In conclusion, the present study replicated findings from recent large-scale studies, but even more so provided important new insights into the differentiated relationships between the two higher-order factors of mindfulness and (sub)components of empathy. Self-Regulation Attention was strongly positively associated with cognitive empathy and Orientation to Experience negatively with affective empathy. Overall, mindfulness seemed to be associated with aspects of empathy which specifically benefit psychological health. For Self-Regulated Attention, emotional awareness could be a key mediator of these relationships. The present findings thus suggest differential roles of Self-Regulated Attention and Orientation to Experience for the links between mindfulness and empathy and highlight the importance of emotional awareness for these associations. Mindfulness interventions could be instrumental for the increase of empathy, which should be investigated in future studies based on the present results.

Limitations

Although promising, the results of this study must be interpreted in light of some limitations. The cross-sectional data did not allow for causal conclusions. In addition, all data were based on self-reports and therefore potentially are susceptible to common-method variance and other, related biases. Longitudinal studies are therefore needed to confirm and replicate the present findings, also by beneficially considering alternative, more objective, measures (e.g., assessing empathy with behavioral tasks, as in the Multifaceted Empathy Test, which would reduce bias due to impression management and socially desirable responding73). Complementary measures could be of particular interest for components of affective empathy that may be partially automatic and not always dependent on conscious control15. For these, self-reports may provide important insights into self-perceptions11, but physiological measures could provide a more direct measurement of emotional reactivity12. Only a selection of potential mediators was examined in this study, and indirect, subscale-level effects of cognitive and affective empathy were not investigated. As well, only trait components of mindfulness and empathy were accounted for, but not their respective state components. Future inquiries along these lines might also fruitfully address the respective state components of these constructs. Meditation experience was included as a background confounder, but potential effects of meditation style, or length of meditation sessions, were not considered. Lastly, larger studies could address potential influences of mediation styles and also investigate associations on the latent level.

Data availability

The data reported in this article is available at https://osf.io/ujp3e.

References

Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness (Delta Trade Paperback/Bantam Dell, 1990).

Thera, N. The Heart of buddhist Meditation: Satipaṭṭhāna: A Handbook of Mental Training Based on the Buddha’s Way of Mindfulness, with an Anthology of Relevant Texts Translated from the Pali and Sanskrit (Buddhist Publication Society, 2005).

Bishop, S. R. et al. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 11, 230–241 (2004).

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A. & Oh, D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 78, 169–183 (2010).

Chiesa, A., Calati, R. & Serretti, A. Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 449–464 (2011).

Donald, J. N. et al. Does your mindfulness benefit others? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the link between mindfulness and prosocial behaviour. Br. J. Psychol. 110, 101–125 (2018).

Fletcher, L. & Hayes, S. C. Relational frame theory, acceptance and commitment therapy, and a functional analytic definition of mindfulness. J. Ration. Emotive Cogn. Behav. Ther. 23, 315–336 (2005).

Lutz, A., Slagter, H. A., Dunne, J. D. & Davidson, R. J. Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 12, 163–169 (2008).

Tran, U. S., Glück, T. M. & Nader, I. W. Investigating the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ): Construction of a short form and evidence of a two-factor higher order structure of mindfulness. J. Clin. Psychol. 69, 951–965 (2013).

Cuff, B. M. P., Brown, S. J., Taylor, L. & Howat, D. J. Empathy: A review of the concept. Emot. Rev. 8, 144–153 (2016).

Reniers, R. L., Corcoran, R., Drake, R., Shryane, N. M. & Völlm, B. A. The QCAE: A questionnaire of cognitive and affective empathy. J. Assess. 93, 84–95 (2011).

Hall, J. A. & Schwartz, R. Empathy present and future. J. Soc. Psychol. 159, 225–243 (2019).

Derntl, B. et al. Generalized deficit in all core components of empathy in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 108, 197–206 (2009).

Morelli, S. A., Rameson, L. T. & Lieberman, M. D. The neural components of empathy: Predicting daily prosocial behavior. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9, 39–47 (2012).

Singer, T. & Lamm, C. The social neuroscience of empathy. Ann. N. Acad. Sci. 1156, 81–96 (2009).

Van Dam, N. T. et al. Mind the Hype: A critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13, 36–61 (2017).

Beitel, M., Ferrer, E. & Cecero, J. J. Psychological mindedness and awareness of self and others. J. Clin. Psychol. 61, 739–750 (2005).

Fulton, C. L. & Cashwell, C. S. Mindfulness-based awareness and compassion: Predictors of counselor empathy and anxiety. Couns. Educ. Superv. 54, 122–133 (2015).

Thomas, J. & Otis, M. Intrapsychic correlates of professional quality of life: Mindfulness, empathy, and emotional separation. J. Soc. Soc. Work Res. 1, 83–98 (2010).

Vilaverde, R., Correia, A. & Lima, C. Higher trait mindfulness is associated with empathy but not with emotion recognition abilities. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 192077 (2020).

Berry, D. R. et al. Mindfulness increases prosocial responses toward ostracized strangers through empathic concern. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 147, 93–112 (2018).

Davis, M. H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 44, 113–126 (1983).

Cooper, D., Yap, K., O’Brien, M. & Scott, I. Mindfulness and empathy among counseling and psychotherapy professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness 11, 2243–2257 (2020).

MacDonald, H. & Price, J. Emotional understanding: Examining alexithymia as a mediator of the relationship between mindfulness and empathy. Mindfulness 8, 1644–1652 (2017).

Baer, R., Smith, G., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J. & Toney, L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 13, 27–45 (2006).

Fuochi, G. & Voci, A. A deeper look at the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and empathy: Meditation experience as a moderator and dereification processes as mediators. Personal. Individ. Differ. 165, 110122 (2020).

Jones, S., Bodie, G. & Hughes, S. The impact of mindfulness on empathy, active listening, and perceived provisions of emotional support. Commun. Res. 46, 838–865 (2019).

Gratz, K. & Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26, 41–54 (2004).

Petrides, K., Gómez, M. & Pérez-González, J. Pathways into psychopathology: Modeling the effects of trait emotional intelligence, mindfulness, and irrational beliefs in a clinical sample. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 24, 1130–1141 (2017).

Jacobs, I., Wollny, A., Sim, C. & Horsch, A. Mindfulness facets, trait emotional intelligence, emotional distress, and multiple health behaviors: A serial two-mediator model. Scand. J. Psychol. 57, 207–214 (2016).

Petrides, K., Pita, R. & Kokkinaki, F. The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. Br. J. Psychol. 98, 273–289 (2007).

Burzler, M., Voracek, M., Hos, M. & Tran, U. Mechanisms of mindfulness in the general population. Mindfulness 10, 469–480 (2019).

Di Girolamo, M., Giromini, L., Winters, C., Serie, C. & de Ruiter, C. The Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy: A comparison between paper-and-pencil versus online formats in Italian samples. J. Pers. Assess. 101, 159–170 (2019).

Tran, U. S. et al. Factorial structure and convergent and discriminant validity of the E (Empathy) scale. Psychol. Rep. 113, 441–463 (2013).

Weisbuch, M., Ambady, N., Slepian, M. L. & Jimerson, D. C. Emotion contagion moderates the relationship between emotionally-negative families and abnormal eating behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 44, 716–720 (2011).

Wheaton, M., Prikhidko, A. & Messner, G. Is fear of COVID-19 contagious? The effects of emotion contagion and social media use on anxiety in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Front. Psychol. 11, 567379 (2021).

Horan, W. P. et al. Structure and correlates of self-reported empathy in schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 66–67, 60–66 (2015).

Westphal, M. et al. Protective benefits of mindfulness in emergency room personnel. J. Affect. Disord. 175, 79–85 (2015).

Boellinghaus, I., Jones, F. W. & Hutton, J. The role of mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation in cultivating self-compassion and other-focused concern in health care professionals. Mindfulness 5, 129–138 (2014).

Brown, K. W. & Ryan, R. M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 822–848 (2003).

Baer, R. A. et al. Construct validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment 15, 329–342 (2008).

Medvedev, O. N. et al. Measuring trait mindfulness: How to improve the precision of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale using a Rasch model. Mindfulness 7, 384–395 (2016).

Tran, U. S. et al. The serenity of the meditating mind: A cross-cultural psychometric study on a two-factor higher order structure of mindfulness, its effects, and mechanisms related to mental health among experienced meditators. PLoS ONE 9, e110192 (2014).

Baron-Cohen, S. & Wheelwright, S. The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 34, 163–175 (2004).

Georgi, E., Petermann, F. & Schipper, M. Are empathic abilities learnable? Implications for social neuroscientific research from psychometric assessments. Soc. Neurosci. 9, 74–81 (2014).

Bonett, D. G. Replication-extension studies. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 21, 409–412 (2012).

Leiner, D. J. SoSci Survey. (2019).

Perugini, M., Gallucci, M. & Costantini, G. Safeguard power as a protection against imprecise power estimates. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9, 319–332 (2014).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160 (2009).

Fritz, M. S. & Mackinnon, D. P. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol. Sci. 18, 233–239 (2007).

Kelley, K. MBESS: The MBESS R Package. (2021).

Gutzweiler, R. & In-Albon, T. Überprüfung der Gütekriterien der deutschen Version der Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale in einer klinischen und einer Schülerstichprobe Jugendlicher. Z. Für Klin. Psychol. Psychother. 47, 274–286 (2018).

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D. & Simonsohn, U. A 21 word solution. Cogn. Soc. Sci. EJournal https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2160588 (2012).

Marsh, H. W., Morin, A. J., Parker, P. D. & Kaur, G. Exploratory structural equation modeling: An integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 10, 85–110 (2014).

Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36 (2012).

Revelle, W. psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research. (2021).

Hattori, M., Zhang, G. & Preacher, K. J. Multiple local solutions and geomin rotation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 52, 720–731 (2017).

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 6, 1–55 (1999).

Funder, D. C. & Ozer, D. J. Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2, 156–168 (2019).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891 (2008).

Nadler, R., Carswell, J. & Minda, J. Online mindfulness training increases well-being, trait emotional intelligence, and workplace competency ratings: A randomized waitlist-controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 11, 255 (2020).

Gutierrez, D. & Mullen, P. Emotional intelligence and the counselor: Examining the relationship of trait emotional intelligence to counselor burnout. J. Ment. Health Couns. 38, 187–200 (2016).

Siebert, D. C., Siebert, C. F. & Taylor-McLaughlin, A. Susceptibility to emotional contagion. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 33, 47–56 (2007).

Blair, R. J. R. Responding to the emotions of others: Dissociating forms of empathy through the study of typical and psychiatric populations. Conscious. Cogn. 14, 698–718 (2005).

Paulhus, D. L. & Williams, K. M. The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Personal. 36, 556–563 (2002).

Irving, J., Dobkin, P. & Park, J. Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: A review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 15, 61–66 (2009).

Cejudo, J. et al. Using a mindfulness-based intervention to promote subjective well-being, trait emotional intelligence, mental health, and resilience in women with fibromyalgia. Front. Psychol. 10, 2541 (2019).

Kiken, L. G., Garland, E. L., Bluth, K., Palsson, O. S. & Gaylord, S. A. From a state to a trait: Trajectories of state mindfulness in meditation during intervention predict changes in trait mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 81, 41–46 (2015).

Bergomi, C., Tschacher, W. & Kupper, Z. Meditation practice and self-reported mindfulness: A cross-sectional investigation of meditators and non-meditators using the Comprehensive Inventory of Mindfulness Experiences (CHIME). Mindfulness 6, 1411–1421 (2015).

Cebolla, A. et al. Exploring relations among mindfulness facets and various meditation practices: Do they work in different ways?. Conscious. Cogn. 49, 172–180 (2017).

Lindsay, E. K. & Creswell, J. D. Mechanisms of mindfulness training: Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Clin. Psychol. Rev. 51, 48–59 (2017).

Dziobek, I. et al. Dissociation of cognitive and emotional empathy in adults with Asperger syndrome using the Multifaceted Empathy Test (MET). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 38, 464–473 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.B. designed the study, participated in the data analysis, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the final manuscript. L.M. participated in the data analysis and reviewed and edited the final manuscript. M.V. reviewed and edited the final manuscript. U.S.T. designed the study, supervised the execution of the study, supervised the data analysis, and reviewed and edited the first draft and the final version of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borghi, O., Mayrhofer, L., Voracek, M. et al. Differential associations of the two higher-order factors of mindfulness with trait empathy and the mediating role of emotional awareness. Sci Rep 13, 3201 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30323-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30323-6

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.