Abstract

There is conflicting evidence concerning the effect of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) on COVID-19 incidence and outcome. Hence, we aimed to evaluate the published evidence through a systematic review process and perform a meta-analysis to assess the association between IBD and COVID-19. A compressive literature search was performed in PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Embase, and Cochrane Library from inception to July 2021. A snowball search in Google, Google Scholar, Research Gate, and MedRxiv; and bibliographic research were also performed to identify any other relevant articles. Quantitative observational studies such as cohort, cross-sectional, and case–control studies that assessed the incidence, risk, and outcomes of COVID-19 among the adult IBD patients published in the English language, were considered for this review. The incidence and risk of COVID-19, COVID-19 hospitalization, the severity of COVID-19, and mortality were considered as the outcomes of interest. The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist was used for quality assessment. A subgroup and sensitivity analysis were performed to explore the heterogeneity and robustness of the results, respectively. A total of 86 studies out of 2828 non-duplicate records were considered for this meta-analysis. The studies were single or multicentric internationally from settings such as IBD centres, medical colleges, hospitals, or from the general public. Most of the studies were observed to be of good quality with an acceptable risk of bias. The pooled prevalence of COVID-19, COVID-19 hospitalization, severe COVID-19, and mortality in the IBD population were 6.10%, 10.63%, 40.43%, and 1.94%, respectively. IBD was not significantly (p > 0.05) associated with the risk of COVID-19, COVID-19 hospitalization, severe COVID-19, and mortality. In contrast, ulcerative colitis was significantly associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 (OR 1.37; p = 0.01), COVID-19 hospitalization (OR 1.28; p < 0.00001), and severe COVID-19 (OR 2.45; p < 0.0007). Crohn’s disease was significantly associated with a lesser risk of severe COVID-19 (OR 0.48; p = 0.02). Type of IBD was a potential factor that might have contributed to the higher level of heterogeneity. There was a significant association between ulcerative colitis and increased risk of COVID-19, COVID-19 hospitalization, and severe COVID-19 infection. This association was not observed in patients with Crohns' disease or in those diagnosed non-specifically as IBD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world is still dealing with a pandemic that was first reported in Wuhan province in December 2019 and the etiological agent was recognized as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS CoV2)1. During this period of one and half years (till 31st August 2021), a total of 217,925,862 cases were identified with a total of 4,524,091 death cases reported across the world2. Many factors including advanced age, obesity, and comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, epilepsy, sarcopenia and schizophrenia were associated with severe COVID-193,4,5,6,7. Moreover, damages to the internal organs such as the heart, liver, and kidneys were identified as major factors linked with severe COVID-19. Other factors such as time to hospital admission, tuberculosis, inflammation disorders, and coagulation dysfunctions also contributed to the higher fatality and mortality in COVID-19 patients3. Factors like current malignant status, dyspnoea, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, elevated C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine levels, oxygen saturation at admission, and use of azithromycin have been associated with mortality in geriatric COVID-19 patients8.

Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBDs) are a group of chronic conditions which affect the small and large intestines. Sustained inflammation in the gut may contribute to permanent damage of the intestine, compromise the quality of life and increase healthcare costs9. In 2017 a total of 6·8 million (6.4–7.3) people were reportedly living with IBD worldwide. Between 1990 and 2017, the age-standardized prevalence rate of IBD hiked from 79.5 (75.9–83.5) to 84.3 (79.2–89.9) persons per 100,000 population, while the death rate decreased from 0.61 (0.55–0.69) to 0.51 (0.42–0.54) per 100,000 population10.

The incidence and risk of COVID-19 in patients with IBD is still inconclusive. Several studies indicate a higher risk of COVID-19 and mortality in patients with IBD along with other factors such as advanced age and comorbidities11,12. In contrast to this, studies conducted by Maconi et al.13 and Ardizzone et al.14 reported a lower risk of COVID-19 in IBD patients. Interestingly, several other studies observed no cases of COVID-19 in the IBD cohorts they investigated15,16,17,18. In presence of all these conflicts, we aimed to identify all the currently available literature and assess the risk and outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with IBD through a comprehensive systematic literature review process and meta-analysis.

Methodology

We followed a PECOS framework (Population, Exposure, Control, Outcome, and Study Design) for the inclusion of relevant studies and adapted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines19 to report this systematic review. Two independent reviewers were involved in the study selection, data extraction and methodological quality assessment and any disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with another reviewer.

Criteria for considering the studies for this review

Participants

We only considered patients who were diagnosed with IBD (CD, UC or IBD-unclassified) or microscopic colitis (MC) as per the author’s discretion in adult patients. Studies involving patients aged less than 18 or a population that included any disease other than IBD were excluded.

Exposure

The exposure or the etiology of interest were diagnosed with IBD such as CD, UC or IBD-unclassified and MC as per the author’s discretion.

Control

The comparator group considered were those who did not have IBD in the case of cohort studies and non-COVID patients in the case of case–control studies.

Outcomes

The outcomes considered were incidence and risk of COVID-19, COVID-19 hospitalization, severity of COVID-19, and mortality. Any studies which did not provide outcomes that were specific to IBD patients were excluded. The outcomes were considered as per author’s discretion or based on the report from authors.

Study designs

The quantitative observational studies such as cohort, cross-sectional (Descriptive and analytical), and case–control studies that assessed the incidence, risk, and/or outcomes of COVID-19 among adult IBD patients were considered for this review. The descriptive cross-sectional studies which presents only the prevalence were termed as prevalence studies and analytical cross-sectional studies marked as cross-sectional studies. Only the studies with full text available in the English language were considered. Reviews, descriptive studies, clinical trials, commentary, guidelines, and qualitative analyses were excluded.

Search methods for identification of studies

A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed/Medline (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/), Embase (https://www.embase.com/#search) and Cochrane Library (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/advanced-search) using all the possible keywords and entry terms in July 2021. We also did a snowball search in Google, Google Scholar Research Gate, and MedRxiv (https://www.medrxiv.org/) to identify any relevant articles. The reference lists of potential articles were also screened to identify additional potentially relevant citations. A detailed search strategy in various databases is provided as Supplementary File S1.

Study selection

All articles identified from databases following the literature search were retrieved to an Excel sheet and screened against the pre-defined criteria. The studies were screened by first reading the title and abstracts followed by reviewing the full text. Only studies that were not excluded at this stage were considered for final inclusion in the review.

Data extraction

The data were abstracted to a comprehensive data extraction form by two independent reviewers. The author’s first name and year of publication were used to identify the studies. The data regarding the publication, study settings, participants, and outcomes were captured from the studies. The number of events and sample size were collected from the studies or calculated from the available data.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist was used to assess the methodological quality and risk of bias of included prevalence studies, cross-sectional studies, case–control studies and cohort studies20. The Joanna Briggs appraisal for prevalence studies addresses the appropriateness of sample frame, study participants, sample size, measure of condition, study setting, data analysis, and response rate. The checklist for cross-sectional studies assessed study aspects such as inclusion criteria, study subjects and setting, measure of exposure, measurement of the condition, confounding factors, outcomes measurement, and the statistical analysis used. The checklist for the case–control studies assessed study aspects such as comparability and matching of population, participant criteria, measurement of exposures, confounding factors, strategies to deal with confounding factors, outcome measurement, follow-up time, and statistical analysis The checklist for the cohort studies assessed study aspects such as recruitment of population, group assignment, measurement of exposures, confounding factors, strategies to deal with confounding factors, outcome measurement, follow-up time, incomplete data, and statistical analysis20.

Evidence synthesis and meta-analysis

All the evidence extracted through the systematic process was summarized narratively and presented in tabular form. Review Man 5.3 was used to conduct the meta-analysis21. The number of events and the total number of participants was used calculate prevalence rates and results were presented in terms of percentage with the 95% confidence interval (CI). The odds ratio (OR) was captured or calculated for the risk outcomes and the results were presented in terms of OR with 95% CI. The I2 statistics were used to estimate the heterogeneity in the analysis. We used the random effect model in case of substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 50%; P < 0.10) during all analyses. To explore the sources of heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analysis based on the type of IBD, wherever possible22.

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Visual inspection of the funnel plot generated through RevMan 5.321 was used to analyse the publication bias wherever feasible, i.e., analyses with minimum of 10 studies22,23,24. Whereas, statistical tests such as Egger’s and Begg’s test using comprehensive meta-analysis (trial version) were performed for all the analyses to check the statistical significance of publication bias. A probability of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The sensitivity analysis was performed to check the robustness of the findings by removing the study with the lowest weight in each analysis and results were provided22.

Results

Study selection process

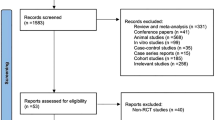

A total of 3733 records were identified from the electronic databases and 40 articles from other resources. Then, a total of 2828 non-duplicate records were initially screened by their title and abstracts, in which 2260 studies were excluded for appropriate reasons. The remaining 568 full-text articles were screened for their eligibility and 86 studies11,12,13,14,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106 were considered for final inclusion in this systematic review and meta-analysis. A detailed study selection is depicted in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of included studies

Among the included studies, 50 studies (58.1%) were published in 2021 and 36 studies (41.9%) in 2020. The majority of studies emerged from the USA (30.23%; n = 26), followed by Italy (20.93%; n = 18), Spain (13.95%; n = 12), Denmark (3.49%; n = 3), France (3.49%; n = 3), the United Kingdom (3.49%; n = 3) Germany (2.32%; n = 2), Iran (2.32%; n = 2), Israel (2.32%; n = 2), and Norway (2.32%; n = 2). The remaining studies were from countries such as Chile (1.16%; n = 1), Egypt (1.16%; n = 1), China (1.16%; n = 1), France & Italy (1.16%; n = 1), India (1.16%; n = 1), Italy & Germany (1.16%; n = 1), Netherlands (1.16%; n = 1), Poland (1.16%; n = 1), Romania (1.16%; n = 1), Saudi Arabia (1.16%; n = 1), Serbia (1.16%; n = 1), and Sweden (1.16%; n = 1); information regarding the country was not available from one study (1.16%; n = 1) as it was a conference abstract. The studies included were single or multi centre; national or international; retrospective or prospective cohort studies, population-based cohort studies, case–control studies, registry analysis, and direct or web-based cross-sectional studies. A total of 34,059,455 participants were included among the studies, out of which 814,633 were IBD patients. The data were collected from IBD centres, medical colleges, hospitals or from the general public. A detailed assessment of characteristics for each included study is illustrated in Table 1.

Risk of bias in the included studies

The quality assessment or risk of bias of included studies for the prevalence and outcomes of COVID-19 patients with IBD is presented in Supplementary File S2. We did not provide a score to the studies as Joanna Briggs's guidance discourages the use of a score cut-off for quality assessment107. Most of the studies were observed as being of good quality with an acceptable risk of bias. Among the prevalence studies, some studies failed to report the method used for the identification of the condition and its reliability. In the case of cross-sectional studies, the risk of bias was attributed to factors such as the identification and dealing with confounding factors in the study. The methodological quality of cohort studies was observed to be good and free of bias.

COVID-19 in patients with IBD

Prevalence of COVID-19

A pooled estimate of 63 studies11,12,14,25,29,31,32,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,49,50,51,52,53,54,58,59,61,66,67,68,69,72,75,77,78,79,80,81,82,85,86,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,98,99,102,103,104,106 indicated an overall prevalence rate of 6.10% (95% CI 3.15–9.04%) of COVID-19 in patients with any IBD. Heterogeneity was very high (I2: 100%); hence a random effect model was used.

Subgroup analysis indicated a prevalence of 9.43% (95% CI − 13.86 to 32.73%; n = 10 studies) of COVID-19 among the patients with CD26,27,28,34,35,45,46,73,76,84 and 8.58% (95% CI − 8.22 to 25.38; n = 10 studies) among those patients with UC27,28,34,35,45,46,55,73,76,84. This analysis indicated that, type of IBD was not a contributing factor to the heterogeneity as there was no change in the level of heterogeneity even after a subgroup analysis (Fig. 2).

Visual inspection of funnel plot observed an obvious asymmetry (Supplementary Fig. S3A) indicating the chances of publication bias which was confirmed by Begg’s test (p = 0.014), but not with Egger’s test (p = 0.087). A sensitivity analysis by removing a study by Singh et al.99 indicated no much difference from the overall pooled estimate (6.07%; 95% CI 3.09–9.06%; 62 studies). The result is provided in Supplementary Fig. S4A.

Risk of COVID-19

A meta-analysis of 22 studies11,12,13,14,31,34,39,44,51,55,58,59,72,75,77,79,83,89,91,92,96,98,105 indicated a non-significant association between the IBD and COVID-19 (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.97–1.37; p = 0.11) compared to non-IBD patients. A significant heterogeneity (I2: 90%) was observed, hence a random effect model was applied.

A Subgroup analysis by type of IBD revealed similar non-significant association with CD patients (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.67–1.15; p = 0.33; n = 9 studies)14,31,39,55,59,79,92,96,98. Whereas, UC was significantly associated with a higher risk of COVID-19 (OR 1.37; 95% CI 1.07–1.74; p = 0.01; n = 9 studies)11,39,55,75,79,91,92,96,98 compared to the non-UC patients. However, the heterogeneity was not observed or non-significant when we performed a subgroup analysis based on the type of IBD such as CD (I2: 18%) and UC (I2: 0%). This indicates that the type of IBD might have contributed to the variation observed among the study findings (Fig. 3).

Visual inspection of funnel plot does not show an obvious asymmetry which is suggestive no publication bias (Supplementary Fig. S3B) which was further confirmed by Egger’s (p = 0.999) and Begg’s test (p = 0.649). A sensitivity analysis by removing single study by Grunert et al.105 estimated no changes in the actual results (OR 1.16; 95% CI 0.97–1.38; 21 studies). The results are provided in Supplementary File S4B.

COVID-19 hospitalization among the patients with IBD

Prevalence of COVID-19 hospitalization

A total of 32 studies11,25,27,31,33,34,37,38,47,48,49,51,52,53,57,60,65,67,68,70,71,72,74,76,77,79,81,85,94,95,100,101 reported COVID-19-related hospitalizations among IBD patients and a pooled estimate identified that 10.63% (95% CI 6.67–14.60%) of IBD patients were admitted to the hospital. There was high heterogeneity (I2: 100%) observed among the studies and random effect model was applied.

Subgroup analysis observed that, only two studies57,76 recorded the COVID-19-related hospitalization rate in patients with CD and UC separately, which was 9.43% (95% CI − 7.90 to 26.75%) and 11.85% (95% CI − 9.25, 32.95%), respectively. No change was in heterogeneity was observed after subgroup analysis based on the type of IBD (Fig. 4).

Visual inspection of funnel plot observed an obvious asymmetry suggestive of publication bias (Supplementary File S3C) which was not confirmed through Egger’s (p = 0.907) and Begg’s (p = 0.252) test. A sensitivity analysis by removing single study estimated no much changes in actual results (10.94; 95% CI 6.92, 14.96; 31 studies). The results are provided in Supplementary File S4C.

Risk of COVID-19 hospitalization

A pooled estimate of 13 studies12,13,27,48,49,50,57,63,72,77,94,99,101 indicated that IBD (OR 1.08; 95% CI 0.87–1.33; p = 0.50) was not significantly associated with risk of COVID-19 associated hospitalization. A random-effect model was used for the analysis as there was significant heterogeneity (I2: 87%).

The subgroup analysis recorded a significantly higher risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization in UC patients (OR 1.28; 95% CI 1.19–1.38; p < 0.00001; n = 4 studies) compared to non-UC patients27,50,57,94. However, CD (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.84–1.06; p = 0.32; n = 2 studies)48,50 and MC (OR 1.28; 95% CI 0.95–1.72; p = 0.11; 1 study)60 was not significantly associated with risk of COVID-19 associated hospitalization. There was a non-significant heterogeneity after the subgroup analysis based on the type of IBD such as CD and UC (I2: 0%). This indicates that type of IBD might be a significant factor that contributed to the variation observed among the study findings (Fig. 5).

The visual inspection of funnel plot observed an obvious asymmetry (Supplementary File S3D) suggestive of publication bias which was not confirmed by Egger’s (p = 0.325) and Begg’s (p = 0.228). A sensitivity analysis by removing Maconi et al.13 observed no changes in the actual findings (OR 1.10; 95% CI 0.89–1.36; 12 studies). The result is provided in Supplementary File S4D.

Severity of COVID-19 in patients with IBD

The severity of COVID-19 among IBD patients was reported in 19 studies11,35,46,49,53,65,66,70,74,77,78,79,80,81,82,87,89,95,101. The meta-analysis of these studies recorded that 7.95% (95% CI 1.10–57.26%; n = 9 studies) had mild disease35,46,53,66,78,79,80,81,82, 2.86% (95% CI 0.92–8.91%, n = 1 study) had moderate disease35 and 40.43% (95% CI 0.05–31,869.21%; n = 14 studies) had severe COVID-1911,35,46,49,65,70,74,77,79,82,87,89,95,101 in the IBD population. A significant level of heterogeneity (I2: 100%) was observed among the studies, hence a random effect model was used for the analysis (Fig. 6).

The visual inspection of funnel plot observed an obvious asymmetry (Supplementary File S3E) suggestive of publication bias which was confirmed by Egger’s (p = 0.025) and Begg’s (p = 0.0002). The sensitivity analysis was not performed for this analysis.

Risk of severe COVID-19 in patients with IBD

A summary estimate of 9 studies30,31,63,77,79,83,94,99,101 indicated no association between IBD and severe COVID-19 (OR 1.05; 95% CI 0.73–1.49; p = 0.80) compared to non-IBD patients. A substantial level of heterogeneity (I2: 66%) was observed, hence random effect model was applied.

The subgroup analysis indicated that CD patients30,79 had a significantly lesser risk of severe COVID-19 (OR 0.48; 95% CI 0.26–0.89; p = 0.02; 2 studies) while UC patients30,79,94 had a significantly higher risk of severe COVID-19 (OR 2.45; 95% CI 1.46–4.11; p < 0.0007; 3 studies). There was non-significant risk of severe COVID-19 with MC (OR 1.39; 95% CI 0.95–2.03; p = 0.09; 1 study)63 and IBD-unclassified (IBD-U) (OR 0.62; 95% CI 0.17–2.25; p = 0.47; 1 study)30. The heterogeneity observed in the overall analysis was not observed in subgroup analysis based on the type of IBD such as CD and UC (I2: 0%). This indicates that type of IBD might be a significant factor that contributed to the variation observed among the study findings (Fig. 7).

The visual inspection of funnel plot observed no obvious asymmetry (Supplementary File S3F) which is suggestive of no publication bias which was confirmed by Egger’s (p = 0.159) and Begg’s (p = 0.272). The sensitivity analysis by removing Burke et al.79 indicated no changes in overall results (OR 1.02; 95% CI 0.71–1.47). The result is provided in Supplementary File S4E.

Mortality in COVID-19 IBD patients

A pooled analysis of 24 studies25,26,27,33,34,38,47,48,57,60,65,67,72,74,76,77,79,82,86,89,94,95,101 estimated an overall mortality rate of 1.94% (95% CI 1.29–2.59%) in COVID-19 patients with IBD. A significant level of heterogeneity (I2: 98%) was observed among the studies.

Subgroup analysis indicates that, a single study76 reported mortality rate of 0.14% (95% CI − 1.82 to 2.10%) in CD patients and an estimate of 3 studies26,57,76 indicated a mortality rate of 2.79% (95% CI 0.60–4.99%) in patients with UC. The subgroup analysis based on the type of IBD did not alter the level of heterogeneity indicative of its non-contribution in heterogeneity (Fig. 8).

The visual inspection of funnel plot observed no obvious asymmetry (Supplementary File S3F) which is suggestive of no publication bias which was confirmed by Egger’s (p = 0.348) and Begg’s (p = 0.881). A sensitivity analysis by removing the study by Axelrad et al.67 indicated no changes in overall results (OR 1.90; 95% CI 1.30–2.62). The result is provided in Supplementary File S4F.

Risk of death or mortality

A meta-analysis of 11 studies11,12,13,27,48,50,51,57,62,77,101 observed that IBD was not significantly associated with COVID-19-related mortality (OR 2.31; 95% CI 0.78–6.81; p = 0.13) compared to non-IBD patients. A random-effect model was used as there was a significant level of heterogeneity (p < 0.10; I2: 98%).

The subgroup analysis also observed the similar non-significant association with CD (OR 6.28; 95% CI 0.55, 72.07; p = 0.14; 2 studies) and UC (OR 4.51; 95% CI 0.78–26.15; p = 0.09; 4 studies) compared to non-CD48,50 and non-UC participants11,27,50,57, respectively. There was no change in the level of heterogeneity (Fig. 9).

The visual inspection of funnel plot observed no obvious asymmetry (Supplementary File S3H) which is suggestive of no publication bias which was confirmed by Egger’s (p = 0.849) and Begg’s (p = 0.881) (Fig. 10). A sensitivity analysis by removing the study by Maconi et al.13 indicated no changes in overall results (OR 2.29; 95% CI 0.75–6.94). The result is provided in Supplementary File S4G.

Discussion

As there is conflicting evidence with respect to the incidence of COVID-19 in patients with IBD, the currently available guidelines for IBD management support the continuation of the use of biologics such as tofacitinib, ustekinumab, and vedolizumab108. Moreover, existing evidence fails to establish a positive association between the use of biologics or immunosuppressives with the risk of COVID-1979. Additionally, biologics use was associated with a lower risk of COVID-19 hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and mortality among IBD patients107. Most of the studies were from the USA, Italy, and Spain, and the remaining countries were observed to have a lesser number of studies from an IBD population. This is an indication of underreporting, which might be due to a lack of manpower or test kits, and other barriers to access the data and patients107.

The findings from the current meta-analysis indicate an overall prevalence of 6.10% (95% CI 3.15–9.04%) of COVID-19 in patients with IBD. Moreover, a significant association could not be identified from the risk estimate (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.97–1.37; p = 0.11). Similarly, a previous meta-analysis by Singh et al., suggested no difference in risk of COVID-19 in IBD patients when compared to the general population107. However, their findings with regards to the association between the risk of COVID-19 and type of IBD differed from our observation. They recorded a non-significant risk in both CD and UC patients, whereas our analysis showed a significantly higher risk in UC patients (OR 1.37; 95% CI 1.07–1.74; p = 0.01). This might be due to the single comparison group that was used by Singh et al., which is the general population. Interestingly, the meta-analysis of 14 studies performed by Tripathi et al., recorded a similar observation in which they recorded a very low incidence (1.01%) of COVID-infection in IBD cohort. Their therapy based analysis revealed a significantly poorer outcomes among those on corticosteroids or mesalamine, though anti-TNFs group had a better outcomes108. These findings were strengthened by another meta-analysis conducted by Alrashed et al.109,110. They also posed a higher risk with other management such as 5-aminosalicylic acid. However, use of vedolizumab, tofacitinib, and immunomodulators alone or in combination with anti-TNF were not associated with severe disease, rather anti-TNFs, and ustekinumab had a better outcomes. The reported COVID-19 hospitalization rate was 10.63% (95% CI 6.67–14.60%) in patients with IBD, which was lesser in the CD (9.43%; 95% CI − 7.90 to 26.75%) and higher in UC (11.85%; 95% CI − 9.25, 32.95%) subtypes, respectively. A similar trend was observed with the risk of COVID-19 hospitalization, where a non-significant association was found in the overall IBD population (p = 0.50), CD (p = 0.32), and MC (p = 0.11) patients. Moreover, the risk of COVID-19 hospitalization was significantly higher among patients with UC (p < 0.00001). The severe nature of disease, high level of immunosuppression, and higher hospitalization rate might have contributed to a significantly higher rate of COVID-associated hospitalization and severity in patients with UC than CD107,111.

We could observe through our meta-analysis that 7.95% and 2.86% of IBD patients had mild and moderate disease, though a higher percentage (40.43%; 95% CI 0.05–31,869.21%) had severe COVID-19. A non-significant association was observed between severe COVID-19 and IBD (p = 0.80), MC (p = 0.09) and IBD-U (p = 0.47). In contrast, a significantly lesser risk was observed in CD patients (OR 0.48; p = 0.02) and significantly higher risk in UC patients (OR 2.45; p < 0.0007). Along with the nature of the disease, factors such as advanced age of ≥ 65 years72,79, unvaccinated status89, CC subtype, use of oral steroids and proton pump inhibitors, rs13071258 A variant63, female gender, obesity, and concomitant diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma79 were associated with a higher risk of severe COVID-19 in IBD patients.

The pooled mortality rate was found to be 1.94%, 0.14%, and 2.79% in IBD, CD, and UC patients respectively. A non-significant association was observed between the COVID-19 mortality and IBD (p = 0.13) and subtypes such as CD (p = 0.14) and UC (p = 0.09). Comparatively, studies by Bezzio et al. (OR 8.45)11, and Ludvigsson et al. (OR 1.92)77 recorded significantly higher mortality in IBD patients. Similarly, Xu et al.50 and Bezzio et al.11 recorded significantly higher mortality in CD (OR 19.93) and UC (OR 22.65) patients, respectively. The evidence indicates that many other factors, such as the use of biologics12, advanced age11,42,95, active IBD status, higher Charlson comorbidity index score11, comorbidities, use of corticosteroids48,101,112 and thiopurines101 were significantly associated with COVID-19 mortality in the IBD population. Very recent evidence also indicates a non-significant effect of corticosteroids in mortality among patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), although positive evidence is reported in more recent randomized clinical trials113. Hence, the use of corticosteroids needs to be monitored in the general population as well as in IBD patients with COVID-19 or ARDS.

There was a significant level of heterogeneity observed in the pooled analysis of all outcomes such as the risk of COVID-19, COVID-19 hospitalization, and severe COVID-19, except for the mortality analysis. Through the subgroup analysis, we found that the type of IBD might have contributed to the heterogeneity as the heterogeneity decreased or became non-significant following the subgroup analysis based on the type of IBD. The risk of bias was observed to be lesser in our included studies which indicates a good quality of the studies. Our sensitivity analysis, which was done by removing the studies with the lowest weight, revealed the robustness of our findings by yielding a non-differing result from the original results.

Conclusions

The current evidence indicates that UC is significantly associated with a higher risk of COVID-19, COVID-19 hospitalization, and severe COVID-19 compared to non-UC participants. Additionally, CD patients had a significantly lesser risk of severe COVID-19 compared to non-CD patients. However, no significant association was observed between higher risk of COVID-19, COVID-19 hospitalization, severe COVID-19, and COVID-19 mortality among those who had been diagnosed non-specifically with IBD compared to non-IBD patients.

References

Khan, S., Gionfriddo, M. R., Cortes-Penfield, N., Thunga, G. & Rashid, M. The trade-off dilemma in pharmacotherapy of COVID-19: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and implications. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 21(15), 1821–1849 (2020).

Worldometer. COVID-19 CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC: Worldometer; 2021 [updated 31 August 2021. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed on 03 September 2021.

Wolff, D., Nee, S., Hickey, N. S. & Marschollek, M. J. I. Risk factors for Covid-19 severity and fatality: A structured literature review. Infection 49(1), 15–28 (2021).

Siahaan, Y. M. T., Ketaren, R. J., Hartoyo, V. & Hariyanto, T. I. Epilepsy and the risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Epilepsy Behav. 125, 108437 (2021).

Siahaan, Y. M. T., Hartoyo, V., Hariyanto, T. I. & Kurniawan, A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) outcomes in patients with sarcopenia: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 48, 158–166 (2022).

Rashid, M., Rajan, A. K., Thunga, G., Shanbhag, V. & Nair, S. Impact of diabetes in COVID-19 associated mucormycosis and its management: A non-systematic literature review. Curr. Diabetes Rev. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573399818666220224123525 (2022).

Pardamean, E., Roan, W., Iskandar, K. T. A., Prayangga, R. & Hariyanto, T. I. Mortality from coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 75, 61–67 (2022).

BağSoytaş, R. et al. Factors affecting mortality in geriatric patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 51(2), 454–463 (2021).

Fakhoury, M., Negrulj, R., Mooranian, A. & Al-Salami, H. Inflammatory bowel disease: Clinical aspects and treatments. J. Inflamm. Res. 7, 113–120 (2014).

GBD 2017 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5(1), 17–30 (2020).

Bezzio, C. et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 in 79 patients with IBD in Italy: An IG-IBD study. Gut 69(7), 1213–1217 (2020).

Belleudi, V. et al. Direct and indirect impact of COVID-19 for patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Med. 10(11), 2388 (2021).

Maconi, G. et al. Risk of COVID 19 in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases compared to a control population. Dig. Liver Dis. 53(3), 263–270 (2021).

Ardizzone, S. et al. Lower incidence of COVID-19 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with non-gut selective biologic therapy. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 36, 3050–3055 (2021).

Fiorino, G. et al. Absence of COVID-19 infection in patients accessing IBD unit at Humanitas, Milan: Implications for postlockdown measures. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 115(10), 1719–1721 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. The symptoms and medications of patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Hubei Province after COVID-19 epidemic. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2847316 (2020).

Viola, A. et al. Management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and outcomes during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. Dig. Liver Dis. 53(6), 689–690 (2021).

Mak, J. W. Y., Weng, M. T., Wei, S. C. & Ng, S. C. Zero COVID-19 infection in inflammatory bowel disease patients: Findings from population-based inflammatory bowel disease registries in Hong Kong and Taiwan. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 36(1), 171–173 (2021).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed). 339, b2535 (2009).

Moola, S. et al. Conducting systematic reviews of association (etiology): The Joanna Briggs Institute’s approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 13(3), 163–169 (2015).

Centre TNC. Review Manager 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

Higgins, J. P. et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Wiley, 2019).

Rashid, M., Shamshavali, K. & Chhabra, M. Efficacy and safety of nilutamide in patients with metastatic prostate cancer who underwent orchiectomy: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 14(2), 108–115 (2019).

Mark, K. et al. Survival benefits of N-acetylcysteine in rodenticide poisoning: Retrospective evidence from an Indian tertiary care setting. Curr. Rev. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. 16(2), 201–208 (2021).

Marafini, I. et al. Low frequency of COVID-19 in inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig. Liver Dis. 52(11), 1234–1235 (2020).

IzquierdoSantervás, S., Casas Machado, P. & Fernández, S. L. Influence of the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the diagnosis and treatment of ulcerative colitis. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas: organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Patologia Digestiva 113(2), 151–152 (2021).

Attauabi, M. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019, immune-mediated inflammatory diseases and immunosuppressive therapies—A Danish population-based cohort study. J. Autoimmun. 118, 102613 (2021).

Moum, K. M., Moum, B. & Opheim, R. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease on immunosuppressive drugs: Perspectives’ on COVID-19 and health care service during the pandemic. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 56(5), 545–551 (2021).

Suárez Ferrer, C., Pérez Robles, T. & Martín-Arranz, M. D. Adherence to intravenous biological treatment in inflammatory bowel disease patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas: organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Patologia Digestiva. 113(2), 154 (2021).

Lamb, C. A. et al. Letter: Risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes associated with inflammatory bowel disease medications-reassuring insights from the United Kingdom PREPARE-IBD multicentre cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 53(11), 1236–1240 (2021).

Richter, V., Bermont, A., Cohen, D. L., Broide, E. & Shirin, H. Effect of inflammatory bowel disease and related medications on COVID-19 incidence, disease severity, and outcome: The Israeli experience. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 34, 267–273 (2022).

Caron, B., Neuville, E. & Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Inflammatory bowel disease and COVID-19 vaccination: A patients’ survey. Dig. Dis. Sci. 67, 2067–2073 (2021).

Sperger, J. et al. Development and validation of multivariable prediction models for adverse COVID-19 outcomes in IBD patients. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.15.21249889 (2021).

Ben-Tov, A. et al. BNT162b2 messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Preliminary real-world data during mass vaccination campaign. Gastroenterology 161, 1715-1717.e1 (2021).

Markovic, S. et al. The effect of COVID-19 resurgence on morbidity and mortality in patients with IBD on biologic therapy. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27(8), e90 (2021).

Botwin, G. J. et al. Adverse events following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.30.21254607 (2021).

Mahmud, N. et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism among patients with inflammatory bowel disease who contract severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Gastroenterology 161, 1709-1711.e1 (2021).

Meyer, A. et al. Risk of severe COVID-19 in patients treated with IBD medications: A French nationwide study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 54(2), 160–166 (2021).

Berte, R. et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV2 in IBD patients treated with biologic therapy. J. Crohns Colitis 15(5), 864–868 (2021).

Khan, N. et al. Are patients with inflammatory bowel disease at an increased risk of developing SARS-CoV-2 than patients without inflammatory bowel disease? Results from a nationwide veterans’ affairs cohort study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 116(4), 808–810 (2021).

Fernández Álvarez, P. et al. Views of patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: ACCU survey results. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas: organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Patologia Digestiva 113(2), 92–97 (2021).

Rottoli, M. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease patients requiring surgery can be treated in referral centres regardless of the COVID-19 status of the hospital: Results of a multicentric European study during the first COVID-19 outbreak (COVID-Surg). Updates Surg. 73, 1811–1818 (2021).

Refaie, E. et al. Impact of the lockdown period due to the COVID-19 pandemic in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 45, 114–122 (2022).

Newsome, R. C. et al. The gut microbiome of COVID-19 recovered patients returns to uninfected status in a minority-dominated United States cohort. Gut Microbes 13(1), 1–15 (2021).

Navarro-Correal, E. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the activity of advanced-practice nurses on a reference unit for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 44(7), 481–488 (2021).

Gubatan, J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 testing, prevalence, and predictors of COVID-19 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Northern California. Gastroenterology 159(3), 1141–4.e2 (2020).

Rodríguez-Lago, I. et al. Characteristics and prognosis of patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in the Basque Country (Spain). Gastroenterology 159(2), 781–783 (2020).

Brenner, E. J. et al. Corticosteroids, but not TNF antagonists, are associated with adverse COVID-19 outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: Results from an international registry. Gastroenterology 159(2), 481–91.e3 (2020).

Allocca, M. et al. Incidence and patterns of COVID-19 among inflammatory bowel disease patients from the Nancy and Milan cohorts. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18(9), 2134–2135 (2020).

Scaldaferri, F. et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the daily management of biotechnological therapy in inflammatory bowel disease patients: Reorganisational response in a high-volume Italian inflammatory bowel disease centre. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 8(7), 775–781 (2020).

Taxonera, C. et al. 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 52(2), 276–283 (2020).

Quera, R. et al. Impact of COVID-19 on a cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease at a specialised centre in Chile. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 45, 110–112 (2022).

Vadan, R. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease management in a Romanian tertiary gastroenterology center: Challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. JGLD 29(4), 549–553 (2020).

Anushiravani, A. et al. A Supporting system for management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease during COVID-19 outbreak: Iranian experience-study protocol. Middle East J. Dig. Dis. 12(4), 238–245 (2020).

Fumery, M., Matias, C. & Brochot, E. Seroconversion of immunoglobulins to SARS-CoV2 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease patients treated by biologics. J. Crohn’s Colitis 14, 1792–1793 (2020).

Xu, F., Carlson, S. A., Wheaton, A. G. & Greenlund, K. J. COVID-19 hospitalizations among U.S. Medicare beneficiaries with inflammatory bowel disease, April 1 to July 31, 2020. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27(7), 1166–1169 (2021).

Queiroz, N. S. F. et al. COVID-19 outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases in Latin America: Results from SECURE-IBD registry. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 36, 3033–3040 (2021).

Hadi, Y. B. et al. COVID-19 vaccination is safe and effective in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Analysis of a large multi-institutional research network in the United States. Gastroenterology 161, 1336-1339.e3 (2021).

Crispino, F., Brinch, D., Carrozza, L. & Cappello, M. Acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among a cohort of IBD patients from southern Italy: A cross-sectional survey. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27, e134–e135 (2021).

Agrawal, M. et al. COVID-19 outcomes among racial and ethnic minority individuals with inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19, 2210-2213.e3 (2021).

Askar, S. R. et al. Egypt’s second wave of coronavirus disease of 2019 pandemic and its impact on patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JGH Open 5(6), 664–668 (2021).

Kjeldsen, J. et al. Outcome of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients with chronic inflammatory diseases. A population based national register study in Denmark. J. Autoimmun. 120, 102632 (2021).

Khalili, H. et al. Association between collagenous and lymphocytic colitis and risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019. Gastroenterology 160(7), 2585–7.e3 (2021).

Taxonera, C. et al. Innovation in IBD care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a cross-sectional survey on patient-reported experience measures. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27(6), 864–869 (2021).

Agrawal, M. et al. Physician practice patterns in holding inflammatory bowel disease medications due to COVID-19, in the SECURE-IBD Registry. J. Crohns Colitis 15(5), 860–863 (2021).

Ghoshal, U. C. et al. Care of inflammatory bowel disease patients during coronavirus disease-19 pandemic using digital health-care technology. JGH Open 5(5), 535–541 (2021).

Axelrad, J. E. et al. From the American Epicenter: Coronavirus disease 2019 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in the New York City metropolitan area. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27(5), 662–666 (2021).

Kennedy, N. A. et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses are attenuated in patients with IBD treated with infliximab. Gut 70(5), 865–875 (2021).

Dailey, J. et al. 731 Failure to develop neutralizing antibodies following SARS-COV-2 infection in young patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving biologics. Gastroenterology 160(6), S-146 (2021).

Agrawal, M. et al. The impact of vedolizumab on COVID-19 outcomes among adult IBD patients in the SECURE-IBD registry. J. Crohn’s Colitis 15, 1877–1884 (2021).

Agrawal, M. et al. Characteristics and outcomes of IBD patients with COVID-19 on tofacitinib therapy in the SECURE-IBD Registry. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27(4), 585–589 (2021).

Derikx, L. et al. Clinical outcomes of Covid-19 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide cohort study. J. Crohns Colitis 15(4), 529–539 (2021).

Attauabi, M. et al. Prevalence and outcomes of COVID-19 among patients with inflammatory bowel disease—A Danish prospective population-based cohort study. J. Crohns Colitis 15(4), 540–550 (2021).

Ungaro, R. C. et al. Effect of IBD medications on COVID-19 outcomes: Results from an international registry. Gut 70(4), 725–732 (2021).

Łodyga, M. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with higher seroprevalence rates of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 131(3), 226–232 (2021).

Rizzello, F. et al. COVID-19 in IBD: The experience of a single tertiary IBD center. Dig. Liver Dis. 53(3), 271–276 (2021).

Ludvigsson, J. F. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and risk of severe COVID-19: A nationwide population-based cohort study in Sweden. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 9(2), 177–192 (2021).

Schlabitz, F. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and COVID-19: How have patients coped so far?. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 56, e126–e130 (2022).

Burke, K. E. et al. Immunosuppressive therapy and risk of COVID-19 infection in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27(2), 155–161 (2021).

Iborra, I. et al. Treatment adherence and clinical outcomes of patients with inflammatory bowel disease on biological agents during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Dig. Dis. Sci. 66, 4191–4196 (2021).

El Hajra, I. et al. Consequences and management of COVID-19 on the care activity of an Inflammatory Bowel Disease Unit. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas: organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Patologia Digestiva 113(2), 98–102 (2021).

Guerra, I. et al. Incidence, clinical characteristics, and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A single-center study in Madrid, Spain. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27(1), 25–33 (2021).

Orlando, V. et al. Development and validation of a clinical risk score to predict the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection from administrative data: A population-based cohort study from Italy. PLoS One 16(1), e0237202 (2021).

Scucchi, L. et al. Low prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 25(5), 2418–2424 (2021).

Carparelli, S. et al. Worse impact of second wave COVID-19 pandemic in adults but not in children with inflammatory bowel disease: An Italian single tertiary center experience. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 25(6), 2744–2747 (2021).

Calafat, M. et al. Impact of immunosuppressants on SARS-CoV-2 infection in elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 33(8), 2355–2359 (2021).

Parekh, R. et al. Presence of comorbidities associated with severe coronavirus infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 67, 1271–1277 (2022).

Dalal, R. S. et al. COVID-19 vaccination intent and perceptions among patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19(8), 1730–2.e2 (2021).

Khan, N. & Mahmud, N. Effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in a veterans affairs cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease with diverse exposure to immunosuppressive medications. Gastroenterology 161(3), 827–836 (2021).

Khan, N., Mahmud, N., Trivedi, C., Reinisch, W. & Lewis, J. D. Risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection and course of COVID-19 disease in patients with IBD in the Veterans Affair Healthcare System. Gut 70(9), 1657–1664 (2021).

Opheim, R., Moum, K. & Moum, B. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease perspective on COVID-19 and health care service during the pandemic. Gastroenterology 160(3), S69 (2021).

Norsa, L. et al. Asymptomatic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease under biologic treatment. Gastroenterology 159(6), 2229–31.e2 (2020).

Harris, R. J. et al. Life in lockdown: Experiences of patients with IBD during COVID-19. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 7(1), e000541 (2020).

Allocca, M. et al. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease are not at increased risk of COVID-19: A large multinational cohort study. J. Clin. Med. 9(11), 3533 (2020).

Fantini, M. C. et al. Telemedicine and remote screening for COVID-19 in inflammatory bowel disease patients: Results from the SoCOVID-19 survey. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 26(11), e134–e136 (2020).

Viganò, C. et al. COVID-19 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A single-center observational study in Northern Italy. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 26(11), e138–e139 (2020).

Allocca, M. et al. Clinical course of COVID-19 in 41 patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: Experience from humanitas center, Milan. Pharmacol. Res. 160, 105061 (2020).

Lukin, D. J. et al. Baseline disease activity and steroid therapy stratify risk of COVID-19 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 159(4), 1541–4.e2 (2020).

Singh, S. et al. Risk of severe coronavirus disease 2019 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: A multicenter research network study. Gastroenterology 159(4), 1575–8.e4 (2020).

Bezzio, C. et al. Biologic therapies may reduce the risk of COVID-19 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 26(10), e107–e109 (2020).

Hong, S. et al. S0717 Inflammatory bowel disease is not associated with severe outcomes of COVID-19: A cohort study from the United States epicenter. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. 115, S360 (2020).

Lewine, E., Trieu, J., Asamoah, N., Venu, M. & Naik, A. S0727 COVID-19 impact on IBD patients in a tertiary care IBD program. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. 115, S365 (2020).

Mosli, M. et al. A cross-sectional survey on the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on inflammatory bowel disease patients in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 26(5), 263–271 (2020).

Hormati, A. et al. Are there any association between COVID-19 severity and immunosuppressive therapy?. Immunol. Lett. 224, 12–13 (2020).

Grunert, P. C., Reuken, P. A., Stallhofer, J., Teich, N. & Stallmach, A. Inflammatory bowel disease in the COVID-19 pandemic—The patients’ perspective. J. Crohn’s Colitis 14, 1702–1708 (2020).

An, P. et al. Prevention of COVID-19 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Wuhan, China. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5(6), 525–527 (2020).

Singh, A. K., Jena, A., Kumar, M. P., Sharma, V. & Sebastian, S. Risk and outcomes of coronavirus disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 9(2), 159–176 (2021).

Tripathi, K. et al. COVID-19 and outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 28, 1265–1279 (2022).

Alrashed, F., Battat, R., Abdullah, I., Charabaty, A. & Shehab, M. Impact of medical therapies for inflammatory bowel disease on the severity of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 8(1), e000774 (2021).

Alrashed, F., Alasfour, H. & Shehab, M. Impact of biologics and small molecules for inflammatory bowel disease on COVID-19-related hospitalization and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JGH Open 6(4), 241–250 (2022).

Lee, M. H. et al. Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 35(11), 2021–2022 (2020).

Pola, S. et al. Strategies for the care of adults hospitalized for active ulcerative colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10(12), 1315–25.e4 (2012).

Rashid, M. et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids in acute respiratory distress syndrome: An overview of meta-analyses. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 75, e14645 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: M.A., Statistics and prepare figures and tables: N.A. Drafting of the manuscript: M.A., N.A., Critical revision of the manuscript: M.A., N.A., J.Q., M.M. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdulla, M., Mohammed, N., AlQamish, J. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and COVID-19 outcomes: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 12, 21333 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25429-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25429-2

This article is cited by

-

The association between ulcerative colitis and COVID-19 severity: a systematic review and meta-analysis systematic review

International Journal of Colorectal Disease (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.