Abstract

Self-assessment of health status is an important marker of social and health aspects. Haemodialysis is an option for renal replacement therapy that alters daily life and impacts social participation and the performance of tasks that give the subject a socially accepted role. In this scenario, leisure activities have the potential to generate well-being and are associated with several aspects of daily life, but few studies have analysed their relationship with the self-assessment of health status. This is a cross-sectional, census study with 1024 individuals from haemodialysis units of a Southeast Brazilian region, with the application of a questionnaire in 2019. We calculated the difference between the proportions of self-assessment of health status (positive and negative) and the two logistic regression models. The chances of individuals on haemodialysis negatively evaluating their health increase when they do not perform artistic leisure activities (OR 2.15; 95% CI 1.35–3.43), physical and sports activities (OR 3.20; 95% CI 1.86–5.52), intellectual (OR 2.21; 95% CI 1.44–3.41), manuals (OR 1.82; 95% CI 1.22–2.72), social (OR 2.74; 95% CI 1.74–4.31), tourist (OR 2.08; 95% CI 1.37–3.17) and idleness and contemplative (OR 1.92; 95% CI 1.29–2.85). Negative health self-assessment is associated with not practicing artistic, manual, physical and sporting, social, intellectual, tourist, and contemplative leisure activities, which have the function of providing social participation and giving meaning to life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-assessment of health status has been extensively studied1,2,3 because it is a multidimensional health construct that encompasses physical and emotional components, aspects of well-being and life satisfaction4, in addition to sociodemographic factors, such as education5,6 and age6, lifestyle, and behaviour7,8, and those related to mental health9. It is an important marker of social participation in community10 and quality of life11,12, a predictor of morbidity6,13 and mortality14, and indicates the subjective perception in relation to health. It can also be called health perception11,12,15, self-reported health16 and subjective health17.

Despite the diversity of factors that the self-assessment of health status is related to, it is a very simple question about how the person assesses their own health, with the answer in the form of a Likert scale of 4 or 5 points18. These characteristics make it an important indicator to be studied, and there are limited studies on the subject in South America19.

Haemodialysis treatment for chronic kidney disease generates major changes in daily life20, and a lack of social support is one of the factors for individuals to determine their quality of life21. In these situations, for the individual on haemodialysis to better perceive their health, care should not be limited to exclusively clinical-biological issues but should also seek care that is close to the World Health Organization definition of health, which aims at complete physical, psychological and social well-being22,23.

The practice of leisure is a behaviour that generates well-being for the individual24 and helps to explain health promotion and prevention in a more comprehensive way25. Furthermore, we are not aware of studies that assess the self-assessment of health status associated with various leisure activities of people undergoing haemodialysis treatment. Thus, the objective of this study was to analyse the association between self-assessment of the state and leisure practices of people using haemodialysis services in a metropolitan region of south-eastern Brazil.

Methods

Study type and population

This study is an epidemiological, cross-sectional and census study with individuals undergoing haemodialysis treatment in the metropolitan region of a capital city in south-eastern Brazil. All users of haemodialysis services in public, philanthropic, hospitals and private clinics in the investigated region over 18 years of age of both sexes and undergoing haemodialysis renal replacement therapy between February and September 2019 participated in the research. Exclusion criteria were being under contact precautions, not residing in one of the municipalities of the metropolitan region, having been transferred to a hospital inpatient unit, and/or having limitations in understanding or answering the questions due to some acute or chronic medical condition.

Measurements

Data on leisure activities, sociodemographic characteristics, life habits, treatment and clinical characteristics were collected. The data were categorised as follows:

-

(1)

The Self-Assessment of Health Status was assessed with the question, “In general, compared to people of your age, how do you consider your own health status?” With the answer on a 4-point Likert scale (very good, good, bad, and very bad) and categorised as “positive” (combining the answers “very good” and “good”) or “negative” (with the answers “bad” and “very bad”).

-

(2)

To measure leisure practices, the Leisure Practices Scale26 was used. It is a Likert-type scale that assesses eight domains of leisure: artistic (going to the movies, theatre, musical shows, participating in choir groups, etc.), manual (gardening, cooking, making crafts, woodworking, etc.), physical sports (going to the gym, playing ball, hiking, etc.), intellectual (participating in courses, reading, listening to or composing music, etc.), social (going to church, going out with friends, going to parties, visiting family, etc.), tourism (traveling, participate in excursions, take short walks in the city, etc.), virtual (browse the internet, use social networks, play video games), idleness and contemplation (appreciate nature, the sunset, meditate, etc.) with 11 points (from zero to ten, where zero means that the user never practices and ten that he always practices). The responses for each leisure domain were categorised into “no” involvement for those who do not practice leisure activities (zero response) and tertiles referring to the level of involvement. To facilitate the understanding of the analyses, the tertile with the lowest values was called “low” involvement in leisure, the tercile with intermediate values of “medium” involvement and the tercile with higher values of “high” involvement.

-

(3)

Sociodemographic characteristics: sex (“female” or “male”); age group (“18 to 29 years old”, “30 to 59 years old” or “60 years old or more”); schooling in years of study (“less than 8 years”, “9 to 11 years” or “more than 11 years”); income in minimum wage (MW) (“less than one MW”, “more than one to two MW”, “more than two to five MW” or “more than five MW”); self-reported race/colour (“white”, “black” and “brown”)27; marital status (“with a partner” or “without a partner”); and number of people living in the same household (“three or less” or “four or more”).

-

(4)

Characteristics of lifestyle habits: habit of consuming alcoholic beverages (“yes” or “no”); and smoking habit (“no, I never smoked”, “no, I smoked in the past, but I stopped smoking” or “yes, regularly”).

-

(5)

Clinical and treatment characteristics: type of treatment (“public”, “private” or “mixed”); time of chronic kidney disease (“less than 5 years” or “5 years or more”); time on haemodialysis (“less than 2 years” or “2 years or more”); medications used (“less than five” or “five or more”); shift that performs haemodialysis (“morning”, “afternoon” or “evening”); city of treatment and residence (“same city” or “different cities”); self-reported intradialytic complications (“none”, “one to three” or “more than three”); and self-reported illnesses (“two or less” or “three or more”).

Data collection

Data collection took place on the premises of the haemodialysis units during the period of the permanence of the individual in the health service.

A pilot test was carried out in a test and re-test format with an interval of 15 days to assess the reliability and reproducibility of the data collection instrument. The participants were 58 individuals with CKD undergoing haemodialysis treatment in a municipality with more than 100,000 inhabitants located outside the surveyed metropolitan area. Kappa and McNemar test statistics were performed. The adjusted Kappa values for the variables of the Leisure Practices Scale ranged from 0.89 to 0.99, which expressed an almost perfect agreement, and in the McNemar tests, no variable showed a significant tendency towards disagreement at the p-value < 5% level.

Statistical analysis

The normality of the variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Descriptive analysis was presented in absolute and relative frequencies. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to calculate the difference between the proportions of self-rated health status (positive and negative) and the other variables. To calculate the odds ratio, a binomial logistic regression model was used for each dimension of leisure with statistical significance of up to 10% in the association test (p < 0.10), adjusting for sociodemographic variables, life habits, and clinical and treatment characteristics that were related to the self-assessment of health status. The significance level was set at 5% and the confidence interval to 95% (95% CI). Data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistic 25.

Ethics approval

The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences Center of the Federal University of Espírito Santo (UFES), under number 3,002,709 and CAAE 6852817.4.0000.5060 and met the criteria of Resolution No. 466/2012 of the National Health Council. Individuals on haemodialysis who agreed to participate in the research signed the Free and Informed Consent Terms before answering the questionnaire. All the methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

During the period of data collection, 1351 people were on haemodialysis in the haemodialysis units of a capital city in south-eastern Brazil. Of the total, 215 were excluded (137 for being in contact precautions and 78 with understanding limitations). There were 89 losses (67 due to being hospitalised in hospital units for death and seven were before data collection unit data after the beginning of unit collection in hospital units). In addition, of the 1047 eligible individuals, 23 (2.2%) refused to participate and three did not respond to the dependent variable question. Thus, 1021 individuals were included in this study.

The study population consisted predominantly of male individuals (56.7%), aged over 30 and up to 59 years (51.6%), with up to eight years of schooling (51.6%), an income between 1 and two minimum wages (44.6%), of brown race/colour (49.1%), living with a partner (55.7%), and with up to 3 people in the same household (71.1%) (Table 1). Significant differences were found for sex (p < 0.001), years of schooling (p = 0.001) and income (p = 0.001).

Most individuals on haemodialysis used public assistance (75.7%), had less than 5 years of chronic kidney disease (51.5%), 2 years or more of haemodialysis (77.9%), in the morning shift (41.1%), had 3 or more intradialytic complications (78.8%), self-reported having three or more diseases (68.1%), and used less than 5 medications (70.4%). For clinical and treatment variables, significant differences were found for self-reported diseases (p < 0.001) and self-reported intradialytic complications (p = 0.001; Table 2).

For leisure activities, most individuals on haemodialysis reported not being involved in artistic activities (59%), manuals (30.8%), physical and sports activities (67.4%), tourist activities (53.3%), and virtual activities (50.5%). For intellectual activities, most of the sample reported having medium involvement (28.3%), as well as social (30.5%) and idleness and contemplative activities (28.3%). There were significant differences in artistic (p < 0.001), manual (p = 0.062), physical and sports (p < 0.001), intellectual (p < 0.001), social (p < 0.001), tourist activities (p < 0.001), virtual (p = 0.099), and idleness and contemplative activities (p = 0.001; Table 3).

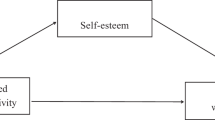

Table 4 presents the model with adjustments for variables with p values less than 10% in the univariate analysis. After adjusting for variables in all domains, 7 of the 8 dimensions of leisure remained associated with self-rated health. When belonging to the group without involvement in leisure, the chances of negatively self-assessing health increased for social (OR 2.74; 95% CI 1.74–4.31), for physical and sports (OR 3.2; 95% CI 1.86–5.52), for tourist (OR 2.08; 95% CI 1.37–3.17), for manual (OR 1.8; 95% CI 1.22–2.72), for artistic (OR 2.15; 95% CI 1.35–3.43), for idleness and contemplative (OR 1.92; 95% CI 1.30–2.85), and for intellectual (OR 2.22; 95% CI 1.44–3.41). For social and intellectual activities, as involvement decreased, the chance of individuals negatively evaluating their health increased.

Discussion

Our study is a pioneer in testing the relationship between the self-rated health status of individuals on haemodialysis and the cultural dimensions of leisure. The use of an instrument that assesses the engagement (frequency and quality) of individuals in leisure is also innovative. We found that individuals on haemodialysis who are not involved in leisure practices are more likely to have a negative self-assessment of health. This relationship occurs because leisure produces moments with the possibility of social interaction and resignification of life, which increases well-being, the perception of health and quality of life. This relationship has no concrete connection with the different leisure activities but rather with the social and subjective aspects that leisure activities provide.

The influence of leisure activities with social content on the self-assessment of health status may be related to favouring social relationships and/or associations. This study showed that the lower the involvement in social leisure activities, the greater the chances of negative self-assessments of their own health. When an individual mentions not having this type of leisure, the chances of a negative self-assessment of health can be close to three times higher. A possible explanation for this relationship is that a worse self-rated health status is associated with less social support28, and individuals in solitude have a negative association with leisure activities29. Haemodialysis requires a routine of long hours in health services and generates difficulties in maintaining leisure activities of the social type at the same frequency and intensity experienced before the beginning of treatment, which can generate unstable psychological conditions and a decrease in the quality of life30. The progressive increase in the chances of a negative self-assessment of health as involvement decreases can be explained by the fact that it is the cultural dimension of leisure that directly involves activities that provide associations with other individuals.

Physical and sports activities also have an impact on strengthening the social relationships of people with chronic diseases31 and are associated with a positive self-assessment of health status32. However, adherence to physical activities by individuals on haemodialysis is positively affected by motivation, anxiety, sleep quality and physical performance33 and is also associated with the strength of social relationships built between people34. In this study, we identified that individuals who reported not performing physical and sports activities were more than three times more likely to negatively evaluate their own health. The health assessment did not change for those who had some engagement with this type of leisure. This relationship indicates that the effect on the self-assessment of health status may be due to situations that favour the creation/strengthening of social bonds rather than the exercise itself.

The chances of negatively self-assessing their own health was higher among haemodialysis users who did not perform tourist activities, while no statistical differences were found between those who performed the most and other levels of engagement. This relationship can also be explained by favouring sociability. A survey carried out in Brazil pointed out that having friends or family members who encourage and make trips and trips together is an important factor in increasing the frequency of leisure activities35. Tourism is also carried out by people looking for experiences related to a greater purpose in life as a way of finding meaning and addressing internal problems36.

This search for new meanings for life and reflection on internal conflicts also explains the relationship between manual, artistic and contemplation leisure activities with the self-assessment of health status. For these leisure activities, differences were found between high and no involvement in leisure activities. Performing manual activities was related to a better perception of health, a feeling of greater control and the possibility of concrete change in the world37. Similarly, the relationship between artistic activities and self-assessment of health status can be explained by the association with multiple aspects of mental health and well-being38, in the awareness of health issues39 and, specifically for people on haemodialysis, are directly proportional to the perception of health they have40, while contemplative and leisure activities arouse positive feelings41. The relationship between leisure activities and health perception is known, and quality of life is an important mediator in this relationship42.

This study showed that the chances of negatively self-assessing health status increased as involvement in intellectual activities decreased, reaching a little more than twice as high among those who did not engage in this leisure activity. This association can be explained by studies indicating that higher levels of education are related to better health perceptions43. Economic, behavioural and health factors positively influence the frequency of intellectual activities throughout life, and these have a positive association with social roles developed for social inequalities44. The progressive increase in the chance of negatively evaluating health as the involvement with this dimension of leisure decreases can be explained by the fact that people undergoing haemodialysis, when developing more intellectual activities, discover new social functions for themselves that are not limited to the role of sick individuals.

We did not identify an association between the self-assessment of health status and involvement in the virtual activities of haemodialysis users in this study. Virtual activities occupy a place of importance in modern life and have the same characteristics as other leisure activities45; however, it must be considered that virtual leisure activities, when carried out in person and mediated only by technology (for example, playing video games with friends in the same real environment), arouse the positive feeling of the encounter46. Virtual activities allow people to star in their own stories and create other worlds, but they need experiences mediated by physical presence to consolidate bonds between individuals, overcoming an era we live in marked by alienation, individualism and loss of the sense of collectivism47.

Finally, this study has some limitations. This was a cross-sectional study; therefore, it was not possible to determine a causal effect between self-rated health status and leisure, but the results may support further studies that point to a causal relationship. The theme of leisure is complex, and there may be relationships with variables that were not considered in this study. However, the use of an instrument that assesses engagement and, therefore, the intensity and evaluation that each individual gives to each dimension of leisure seeks to minimise the difficulties of quantitative research on leisure that does not consider the subjective questions of the participants.

Conclusions

The worst self-assessment of health status of individuals on haemodialysis was associated with not practicing leisure activities, regardless of clinical and treatment characteristics. The establishment of maintaining and/or expanding social relationships and building new social roles and meanings for life after starting haemodialysis treatment are important contributions that leisure activities make to improve the self-assessment of the health status. In this way, treating individuals on haemodialysis with the aim of offering complete well-being, as indicated by the World Health Organization, is a major challenge. It is important that health guidelines reinforce the importance of leisure and that public policies include the benefits of leisure practices for this population. Finally, the effectiveness of this care and the improvement of the health perception of these individuals will be greatly benefited if there are professionals in the multidisciplinary teams who can stimulate, indicate and favour leisure practices.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study may be publicly available from the corresponding author after elimination of identifying information.

References

Petarli, G. B., Salaroli, L. B., Bissoli, N. S. & Zandonade, E. Autoavaliação do estado de saúde e fatores associados: Um estudo em trabalhadores bancários. Cad. Saude Publ. 31, 787–799 (2015).

Sarabi, R. E., Mokhtari, Z., Tahami, A. N., Borhaninejad, V. R. & Valinejadi, A. Assessment of type 2 diabetes patients’ self-care status learned based on the national diabetes control and prevention program in health centers of a selected city. Iran. Koomesh. 23, 465–473 (2021).

de Oliveira, B. L. C. A., Lima, S. F., Costa, A. S. V., da Silva, A. M. & de Britto e Alves, M. T. S. S. Social participation and self-assessment of health status among older people in Brazil. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 26, 581–92 (2021).

Pavão, A. L. B., Werneck, G. L. & Campos, M. R. Autoavaliação do estado de saúde e a associação com fatores sociodemográficos, hábitos de vida e morbidade na população: Um inquérito nacional. Cad. Saude Publ. 29, 723–734 (2013).

Mollaoğlu, M., Başer, E. & Candan, F. Examination of the relationship between health literacy and health perceptions in hemodialysis patients. J. Renal Endocrinol. 7, e11 (2021).

Ogunrinde, B. J., Adetunji, A. A., Muyibi, S. A. & Akinyemi, J. O. Illness perception amongst adults with multimorbidity at primary care clinics in Southwest Nigeria. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 13, e1–e8 (2021).

Tanaka, S., Muraki, S., Inoue, Y., Miura, K. & Imai, E. The association between subjective health perception and lifestyle factors in Shiga prefecture, Japan: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 20, 1786 (2020).

Sayón-Orea, C. et al. Determinants of self-rated health perception in a sample of a physically active population: PLENUFAR VI study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018(15), 2104 (2018).

Luque, B. et al. The role of emotional regulation and affective balance on health perception in cardiovascular disease patients according to sex differences. J. Clin. Med. 9, 3165 (2020).

de Oliveira, B. L. C. A., Lima, S. F., Costa, A. S. V., da Silva, A. M. & de Alves, M. T. S. S. B. E. Social participation and self-assessment of health status among older people in Brazil. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 26, 581–92 (2021).

Oduncuoğlu, B. F., Alaaddinoğlu, E. E., Çolak, T., Akdur, A. & Haberal, M. Effects of renal transplantation and hemodialysis on patient’s general health perception and oral health-related quality of life: A single-center cross-sectional study. Transpl. Proc. 52, 785–792 (2020).

Anna, E. et al. Qualidade de vida e percepção do estado de saúde entre indivíduos hospitalizados. Escola Anna Nery 24, 2020 (2020).

Martins-Silva, T. et al. Health self-perception and morbidities, and their relation with rural work in southern Brazil. Rural Remote Health 20, 5424 (2020).

Kaplan, G. A. et al. Perceived health status and morbidity and mortality: Evidence from the Kuopio ischaemic heart disease risk factor study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 25, 259–265 (1996).

Carneiro, J. A. et al. Autopercepção negative da saúde: Prevalência e fatores associados entre idosos assistidos em centro de referência. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 25, 909–18 (2020).

Opdal, I. M., Larsen, L. S., Hopstock, L. A., Schirmer, H. & Lorem, G. F. A prospective study on the effect of self-reported health and leisure time physical activity on mortality among an ageing population: Results from the Tromsø study. BMC Public Health 20, 1–15 (2020).

Solís-Cámara, P., Meda Lara, R. M., Moreno Jiménez, B., Palomera Chávez, A. & Juárez, R. P. Comparación de la salud subjetiva entre prototipos de personalidad recuperados en población general de México. Acta Colomb. Psicol. 20, 200–213 (2017).

de Barros, M. B. A., Zanchetta, L. M., de Moura, E. C. & Malta, D. C. Auto-avaliação da saúde e fatores associados, Brasil, 2006. Rev. de Saúde Públ. 43(Suppl 2), 27–37 (2009).

van Druten, V. P. et al. Concepts of health in different contexts: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 389 (2022).

Ferreira, B. C. A. et al. Nursing actions and interactions in the recovery of patients with chronic renal failure: Integrative review. Res. Soc. Dev. 10, e49710716861 (2021).

Pan, K. C. et al. Social support as a mediator between sleep disturbances, depressive symptoms, and health-related quality of life in patients undergoing hemodialysis. PLoS ONE 14, e0216045 (2019).

World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata 3 (World Health Organization, 1978).

World Health Organization. World Health Organization Constitution (World Health Organization, 1947).

Mansfield, L., Daykin, N. & Kay, T. Leisure and wellbeing. Leis. Stud. 39, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/0261436720201713195 (2020).

Schmalz, D. L., Janke, M. C. & Payne, L. L. Multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinary research: Leisure studies past, present, and future. J. Leis. Res. 50, 389–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022221620191647751 (2019).

Andrade, R. D. et al. Validade de construto e consistência interna da Escala de Práticas no Lazer (EPL) para adultos. Ciencia e Saude Coletiva 23, 519–528 (2018).

IBGE. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios: Síntese de Indicadores 2015 (Coordenação de Trabalho e Rendimento, 2016).

Wärnberg, J. et al. Lack of social support and its role on self-perceived health in a representative sample of Spanish adults. Another aspect of gender inequality. J. Clin. Med. 10, 1502 (2021).

Chang, L. C., Dattilo, J., Hsieh, P. C. & Huang, F. H. Relationships of leisure social support and flow with loneliness among nursing home residents during the COVID-19 pandemic: An age-based moderating model. Geriatr. Nurs. 42, 1454–1460 (2021).

Takahashi, J. et al. Influence of unstable psychological condition on the quality of life of hemodialysis patients. Renal Replace. Ther. 6, 1–6 (2020).

Skrok, Ł, Majcherek, D., Nałȩcz, H. & Biernat, E. Impact of sports activity on Polish adults: Self-reported health, social capital & attitudes. PLoS ONE 14, e0226812 (2019).

da Silva, P. S. C., de Lima, T. R., Botelho, L. J. & Boing, A. F. Recommendation and physical activity practice in Brazilians with chronic diseases. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 67, 366–372 (2021).

Hornik, B. & Duława, J. Frailty, quality of life, anxiety, and other factors affecting adherence to physical activity recommendations by hemodialysis patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 1827 (2019).

Dalen, H. B., Seippel, Ø., Frahsa, A. & Thiel, A. Friends in sports: Social networks in leisure, school and social media. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 6197 (2021).

Mayor, S. T. S. & Isayama, H. F. O lazer do brasileiro: Sexo, estado civil e escolaridade. In Lazer No Brasil: Representações e Concretizações das Vivências Cotidianas 1st edn (eds Stoppa, E. A. & Isayama, H. F.) 19–36 (Autores Associados, 2017).

Müller, C. V. & Scheffer, A. B. B. Life and work issues in volunteer tourism: A search for meaning? Rev. Admin. Mack. 20, 190095 (2019).

Aranda, L. et al. La importancia de mantenerse activo en la vejez. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2, 13–22 (2017).

Wang, S., Mak, H. W. & Fancourt, D. Arts, mental distress, mental health functioning & life satisfaction: Fixed-effects analyses of a nationally-representative panel study. BMC Public Health 20, 1–9 (2020).

Sonke, J. et al. Health communication and the arts in the United States: A scoping review. Am. J. Health Promot. 35, 106–115 (2021).

de Pasquale, C. et al. Comparison of the CBA-H and SF-36 for the screening of the psychological and behavioural variables in chronic dialysis patients. PLoS ONE 12, e0180077 (2017).

Ferreira, H. G. & Barham, E. J. Relationships between pleasant events, depression, functionality and socio-demographic variables in the elderly. Paideia 28, 15 (2018).

Eifert, E. K., Hall, M., Smith, P. H. & Wideman, L. Quality of life as a mediator of leisure activity and perceived health among older women. J. Women Aging 31, 248–268 (2018).

Yiğitalp, G., Bayram Değer, V. & Çifçi, S. Health literacy, health perception and related factors among different ethnic groups: A cross-sectional study in southeastern Turkey. BMC Public Health 21, 1109 (2021).

Moriya, S., Tei, K., Miura, H., Inoue, N. & Yokoyama, T. Associations between higher-level competence and general intelligence in community-dwelling older adults. Aging Ment. Health 17, 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/136078632012717256 (2013).

Bryce, J. The technological transformation of leisure. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 19, 7–16 (2001).

Lin, C. S., Jeng, M. Y. & Yeh, T. M. The elderly perceived meanings and values of virtual reality leisure activities: A means-end chain approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 663 (2018).

de Cardoso, F. S., Ladislau, C. R., de Souza Neto, G. J. & Alves, R. O. T. Redes sociais e sociabilidade. Rev. do Prog. de Pós-grad. Interdiscipl. em Estudos do Lazer. 22, 91–121 (2019).

Funding

This work was supported by the Research and Innovation Support Foundation of Espírito Santo (FAPES) [grant number 83164324 - FAPES/CNPq/Decit–SCTIE-MS/SESA n° 03/2018 (Research Program for Brazilian Health Unic System)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C.C., E.T.S.N. and L.B.S. designed this study and determined its methods. A.C.C. conducted the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data with assistance from L.B.S. and E.T.S.N. for revising the analytical approach. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. A.C.C. wrote the manuscript and L.B.S. and E.T.S.N. and reviewed of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the development and approval of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cunha, A.C.d., Santos Neto, E.T.d. & Salaroli, L.B. Self-assessment of the health status and leisure activities of individuals on haemodialysis. Sci Rep 12, 20344 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23955-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23955-7

This article is cited by

-

Exploring factors influencing farmers’ health self-assessment in China based on the LASSO method

BMC Public Health (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.