Abstract

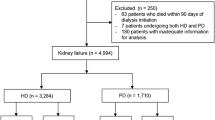

In the general population with COVID-19, the male sex is an established risk factor for mortality, in part due to a more robust immune response to COVID-19 in women. Because patients on kidney function replacement therapy (KFRT) have an impaired immune response, especially kidney transplant recipients due to their use of immunosuppressants, we examined whether the male sex is still a risk factor for mortality among patients on KFRT with COVID-19. From the European Renal Association COVID-19 Database (ERACODA), we examined patients on KFRT with COVID-19 who presented between February 1st, 2020, and April 30th, 2021. 1204 kidney transplant recipients (male 62.0%, mean age 56.4 years) and 3206 dialysis patients (male 61.8%, mean age 67.7 years) were examined. Three-month mortality in kidney transplant recipients was 16.9% in males and 18.6% in females (p = 0.31) and in dialysis patients 27.1% in males and 21.9% in females (p = 0.001). The adjusted HR for the risk of 3-month mortality in males (vs females) was 0.89 (95% CI 65, 1.23, p = 0.49) in kidney transplant recipients and 1.33 (95% CI 1.13, 1.56, p = 0.001) in dialysis patients (pinteraction = 0.02). In a fully adjusted model, the aHR for the risk of 3-month mortality in kidney transplant recipients (vs. dialysis patients) was 1.39 (95% CI 1.02, 1.89, p = 0.04) in males and 2.04 (95% CI 1.40, 2.97, p < 0.001) in females (pinteraction = 0.02). In patients on KFRT with COVID-19, the male sex is not a risk factor for mortality among kidney transplant recipients but remains a risk factor among dialysis patients. The use of immunosuppressants in kidney transplant recipients, among other factors, may have narrowed the difference in the immune response to COVID-19 between men and women, and therefore reduced the sex difference in COVID-19 mortality risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the general population with COVID-19, men exhibit a higher risk of mortality compared with women. In a meta-analysis of over 3 million reported cases of COVID-19 globally, men were reported to have an almost 40% higher likelihood of mortality despite a similar likelihood of having confirmed COVID-19 when compared with women1. Previously it has been shown that women demonstrate a more robust immune response to COVID-19 compared with men and this is suggested to be one of the contributing factors to the observed sex differences in mortality risk2. This line of reasoning also suggests that in an immunocompromised patient population with COVID-19, the sex difference in mortality risk is narrowed or eliminated.

Patients on kidney function replacement therapy (KFRT) have an impaired immune response, especially kidney transplant recipients due to their use of immunosuppressants. Among kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19, some studies indeed showed no sex difference in mortality3,4. However, others demonstrated a higher risk of mortality in men compared with women5. Likewise, among dialysis patients with COVID-19, prior studies reported no to an almost twofold increased risk of mortality in men compared with women6,7,8,9. Importantly, these studies were in general relatively small in size and/or lacked information on key covariates, and therefore lacked power and careful control of these covariates when assessing sex-mortality relationships. Moreover, it remains unclear whether the sex difference in mortality risk differs between kidney transplant recipients and dialysis patients. A better understanding of potential sex-based differences in mortality risk among patients on KFRT with COVID-19 may guide more specific interventions and management of COVID-19 by incorporating sex considerations10.

Therefore, we examined whether sex is associated with the risk for mortality among patients on KFRT with COVID-19. For this study, we used data from the European Renal Association COVID-19 Database (ERACODA), the largest European database with detailed information on patient demographics, comorbidities, symptoms, laboratory results, and prospective follow-up for mortality in patients on KFRT with COVID-19.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

ERACODA was established in March 2020 to study the prognosis and risk factors for mortality among kidney failure patients with COVID-19. Details of the database and the study design have been published previously11. Briefly, adult (≥ 18 years) patients either on dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) or living with a functioning kidney allograft, who were diagnosed with COVID-19 based on a positive result on a real-time polymerase chain reaction assay or rapid antigen test of nasal and/or pharyngeal swab specimens, and/or compatible findings on CT scan or chest X-ray of the lungs were included. Data were voluntarily reported on outpatients and hospitalized patients by physicians responsible for their care. The database currently involves the cooperation of approximately 225 physicians representing over 140 centers in about 35 countries, mostly in Europe.

The database is hosted at the University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands. Data is recorded using REDCap software (Research Electronic Data Capture, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA) for data collection12. Patient information is stored pseudonymized. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University Medical Center Groningen (Netherlands). Since the study did not involve identifiable private information and was observational in nature, a waiver of informed consent was granted by IRB of the University Medical Center Groningen in The Netherlands. Participating centers obtained study approval and waiver of consent from IRBs of their respective institute. All methods were performed per the relevant guidelines and regulations. The clinical and research activities being reported are consistent with the Principles of the Declaration of Istanbul as outlined in the 'Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism'. No organs were procured from prisoners.

Detailed information was collected on patient characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, height, weight, frailty, comorbidities, hospitalization, and medication use) and COVID-19-related characteristics (reason for COVID-19 screening, symptoms, vital signs, and laboratory test results) at presentation. Frailty was assessed using the Clinical Frailty Score developed by Rockwood et al.13. Obesity was defined as a body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2. For the analysis, all patients who presented between February 1st, 2020, and April 30th, 2021, and for whom information on sex, the date of presentation, type of renal replacement therapy, and 3-month mortality was available were included (Fig. S1). The primary outcome was 3-month mortality. The secondary outcome was 28-day mortality.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics are presented by sex (male/female) for dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients, separately. Continuous data are presented as mean (standard deviation (SD)) or as median (interquartile interval (IQI)) in case of a non-Gaussian distribution of data. Categorical data are presented as numbers (percentages). Baseline characteristics were compared between men and women using the independent sample t-test (in case of Gaussian distribution) or the Mann–Whitney U-test (in case of non-Gaussian distribution) for continuous variables and the Pearson Chi-2 test for categorical variables. The standardized difference in baseline characteristics between men and women for both continuous and categorical variables was also calculated. Standardized difference estimates are based only on sample statistics and are not directly influenced by sample size14. A standardized difference of 0.15 or more was used to indicate a relevant difference in baseline characteristics between men and women15.

To investigate the association between sex and mortality risk, hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for the association of sex (male versus female (reference)) with 3-month mortality using Cox proportional-hazards regression models. Multiple models were constructed to account for factors that may explain any observed difference in 3-month mortality between men and women. Model 1 was a crude (unadjusted) model. In Model 2 we adjusted for age (continuous) and clinical frailty score (Continuous). In Model 3, given sex-related differences in access to care16,17,18, we additionally adjusted for the reason for COVID-19 screening (symptoms-based screening/positive COVID-19 contact or routine screening). Model 4 was further adjusted for factors known to be associated with COVID-19 outcome, i.e. smoking (never, current, former), obesity (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), heart failure (yes/no), chronic lung disease (yes/no), coronary artery disease (yes/no), and auto-immune disease (yes/no)19. In the final model (Model 5), we additionally adjusted for the duration of KFRT (years) and estimated the glomerular filtration rate. In dialysis patients, eGFR was assumed to be 0 for those with residual diuresis ≤ 200 mL/day and 5 mL/min/1.73 m2 for those with residual diuresis > 200 mL/day20. The proportional-hazards assumption was investigated by comparing a model with and without the interaction of log(time) with individual covariates. Cumulative incidence was plotted for 3-month mortality by sex. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to compare cumulative incidence between men and women.

To assess the robustness of the association between sex with mortality, we performed several additional analyses. First, to assess the consistency of our results across key subgroups we investigated results by subgroups of age (< 65/ ≥ 65 years), the reason for COVID-19 screening (symptoms-based screening/positive COVID-19 contact or routine screening), frailty (< 4/ ≥ 4), obesity (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), and diabetes (yes/no). Second, assuming immunosuppressant use is among the main factors contributing to excess mortality in kidney transplant recipients compared with dialysis patients and immunosuppressant use affects men and women differently for the risk of mortality in presence of COVID-19, we investigated the association of type of KFRT with mortality by sex. Third, to further account for potential differences in access to care among men and women, we investigated the association between sex and 3-month mortality when starting follow-up from the date of symptom(s) onset. Fourth, to investigate potential sex differences in relatively short-term mortality risk, we examined the association of sex with 28-day mortality instead of 3-month mortality. Fifth, we investigated sex differences in mortality risk by hospitalization and intensive care unit admission status. Finally, to account for the potential influence of between-country differences on the sex-mortality relationship, we constructed a random intercept model with the country as a random factor in a multilevel mixed-effects parametric survival model.

All analyses were performed using Stata version 17.0 (College Station, TX). A 2-sided p-value less than 0.05 was adopted to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the study population by type of KFRT and sex are reported in Table 1. Among a total of 1204 kidney transplant recipients (mean age 56.4 years), 747 (62.0%) were men and 457 (38%) were women. Men on average had lower body mass index and clinical frailty scores compared with women, whereas the prevalence of prior smoking, hypertension, and coronary artery disease was higher among men. The prevalence of auto-immune diseases was higher among women compared with men. Presenting symptoms were largely comparable between men and women except that women more often reported nausea or vomiting.

Among 3206 dialysis patients (mean age 67.7 years), 1981 (61.8%) were men and 1225 (38.2%) were women. Similar to kidney transplant recipients, the prevalence of prior smoking and chronic artery disease was higher among men compared with women and again the prevalence of auto-immune diseases was higher among women. Men more often had fever at presentation and the level of C-reactive protein was also higher among men compared with women.

Three-month mortality

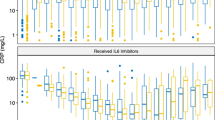

In kidney transplant recipients, 16.9% of men and 18.6% of women died within 3 months of presentation (p = 0.31). Cumulative mortality incidence was similar between men and women (p = 0.57) (Fig. S2). In a crude model, the HR for the risk of 3-month mortality in men (vs women) was 0.90 (95% CI 0.68, 1.18; p = 0.43). In the final multivariable model adjusted model (Model 5), the HR for the risk of 3-month mortality in men vs women was 0.89 (95% CI 0.65, 1.23; p = 0.49) (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Percentage mortality by sex and type of kidney function replacement therapy (A) and hazard ratio for the association of sex (male vs. female (reference)) with 3-month mortality by type of kidney function replacement therapy (B). *Adjusted for: age (continuous), clinical frailty score (continuous), the reason for COVID-19 screening (symptoms-based screening, positive COVID-19 contact or routine screening), smoking (never, current, former), obesity (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), heart failure (yes/no), chronic lung disease (yes/no), coronary artery disease (yes/no), and auto-immune disease (yes/no), duration of kidney function replacement therapy (years) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (continuous). †Adjusted estimate from literature (Nat Commun 2020: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33298944/).

In dialysis patients, 27.1% of men and 21.9% of women died within 3 months of presentation (p = 0.001). Cumulative mortality incidence was higher in men compared with women (p < 0.001) (Fig. S2). In a crude model, the HR for the risk of 3-month mortality in men vs women was 1.27 (95% CI 1.10, 1.47; p = 0.001) and in the fully adjusted model, it was 1.33 (95% CI 1.13, 1.56, p = 0.001) in dialysis patients (Table 2; Fig. 1).

The interaction between sex and type of KFRT for mortality risk was statistically significant (p for interaction = 0.02). No violation of the proportional hazards assumption was noted in the fully adjusted model for kidney transplant recipients nor for dialysis patients (p-value for difference between the model with and without interaction between log(time) and covariates being 0.41 in case of kidney transplant recipients and 0.75 in case of dialysis patients).

Additional analyses

The observed association between sex and 3-month mortality risk in kidney transplant recipients and dialysis patients was consistent across all examined subgroups except across the subgroup of obesity (no/yes) in dialysis patients where the association was particularly evident among non-obese patients (Fig. 2).

In a fully adjusted model, the HR for the risk of 3-month mortality in kidney transplant recipients (vs. dialysis patients) was 1.39 (95% CI 1.02, 1.89, p = 0.04) among men and was 2.04 (95% CI 1.40, 2.97, p < 0.001) among women (p for interaction = 0.02) (Table 3). When the follow-up period was considered to start from the date of symptom(s) onset, the association between sex and 3-month mortality remained statistically non-significant among kidney transplant recipients and statistically significant among dialysis patients (Table S1). When investigating the association between sex and mortality for 28-day mortality, by hospitalization status or by ICU admission status, results were essentially similar to our main findings (Tables S2, S3, and S4 respectively). Finally, the observed association between sex and 3-month mortality risk in kidney transplant recipients and dialysis patients remained unchanged when accounting for potential between-country differences in the relationship between sex and mortality (Table S5).

Discussion

In this large study of patients on KFRT with COVID-19, men were at higher risk of mortality in dialysis patients, whereas mortality risk was similar in males and females in kidney transplant recipients. The observed association between sex and mortality risk in dialysis and transplant patients was consistent across key subgroups except across subgroups according to body mass index in dialysis patients where the increased risk of mortality in men was particularly high among non-obese patients. Importantly, when men and women were investigated separately for the association of type of KFRT with mortality, there was less difference in the adjusted risk of mortality between kidney transplant recipients and dialysis patients among men compared with women.

Studies in the early phase of the pandemic that investigated the sex-mortality relationship among kidney transplant recipients were relatively small and reported no difference in mortality between men and women. However, it remained unclear whether men and women continued to exhibit a similar risk of mortality as more data accumulated. A recent large retrospective study among solid organ transplant recipients suggested a 47% higher risk of mortality in men compared with women in kidney transplant recipients when accounting for differences in patient characteristics5. Unfortunately, due to the retrospective nature, this study had a considerable number of missing records for comorbidities and due to miscoding, a substantial number of these patients may have been misclassified as not having comorbidity. It is worth noting that in the case of other infectious diseases, such as influenza, where men are reported to have an increased risk of mortality in the general population21,22, sex has also been reported not to be associated with mortality in immunocompromised study populations23.

The use of immunosuppressants may be one of the reasons for the lack of difference in risk of mortality between men and women in kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19. Previously it has been demonstrated that in the general population with COVID-19, men have increased plasma levels of innate immune cytokines such as IL-8 and IL-18 along with more robust induction of monocytes, whereas women show more robust T cell activation compared with men2. This study also demonstrated that higher levels of innate immune cytokines and poor T-cell response were associated with poor outcomes, suggesting a more robust immune response to COVID-19 potentially contributes to the survival advantage among women2. However, among kidney transplant recipients, which typically are on maintenance immunosuppression, any survival advantage due to a robust immune response may be mitigated.

Among dialysis patients with COVID-19, our results are in line with other larger studies published later in the COVID-19 pandemic which also showed an increased risk of mortality in men compared with women8,9. Earlier studies, however, did not specifically aim to investigate the sex-mortality relationship and lacked careful control of factors that may explain the excess risk of mortality among men6,7,8,9,24. Consequently, it was unclear whether the association between sex and mortality in dialysis patients was independent of potential sex differences in comorbidities and high-risk behaviours including those related to access to health care. Our study demonstrated that the association between sex and mortality persists independent of comorbidities and factors related to healthcare access, and in our study, we additionally accounted for clinical frailty score and potential sex differences in the time from symptom(s) onset to clinical presentation to limit the possibility of residual influence from comorbidities and factors related to health care access.

Dialysis patients have impaired immune function which may influence the sex-mortality relationship in this population compared with the general population when infected with COVID-19. Among dialysis patients in our study, the risk of mortality was about 30% higher in men compared to women. In the general population with COVID-19, a meta-analysis including 92 studies and 3,111,714 subjects reported an almost 40% higher likelihood of mortality in men1. When this analysis was repeated after accounting for reporting bias, the likelihood of mortality in men was estimated to be even about 64% higher in men compared with women. Other studies in the general population with COVID-19 that were not included in the aforementioned meta-analysis, with similar mean age and design as our study, reported an almost twofold higher adjusted risk of mortality in men compared with women25. These mortality risks appear higher than the 1.39 increased mortality risk that we found in male versus female patients on dialysis. These data suggest that the sex difference in mortality risk among dialysis patients may be narrower compared to the sex difference in mortality risk among the general population with COVID-19.

Our results also demonstrated that the absolute risk of mortality is lower in kidney transplant recipients compared with dialysis patients. However, it should be noted that after adjustment for differences in age, frailty, and comorbidities between these two patient groups, the risk of mortality is actually higher among kidney transplant recipients compared with dialysis patients20. Differences in risk of mortality by type of KFRT and sex were apparent when we analyzed male–female kidney transplant recipients and dialysis patients together in one combined dataset (Table S6).

Our findings imply that sex may be an important factor in the management of patients on KFRT with COVID-19. Male dialysis patients should be informed about their higher risk of complications compared with females when infected with COVID-19 and be advised when in doubt to seek medical attention in the case of (suspected) COVID-19.

The present study has a number of strengths. This study includes detailed information on key patient and disease characteristics and prospective information on mortality from a large number of dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19, which allowed a comprehensive assessment of the sex-mortality association including a direct comparison of the sex-mortality relationship between kidney transplant recipients and dialysis patients. This study was also able to investigate the association between sex and mortality by reason for COVID-19 screening which is particularly relevant given the sex difference in health care seeking behaviour16,17,18. However, this study also has limitations. First, we did not collect the information on viral load. Therefore, we were not able to investigate whether males and females differed in their viral load. Second, we only had data available from patients infected with wild-type or early variants of COVID-19 (e.g. alpha and delta)26. To our knowledge, there has also been no evidence that one viral strain/mutation affected the sex difference in mortality risk more than others. Moreover, data in our study were collected before mass vaccination was rolled out and before the efficacy of any of the currently known pharmacological treatments (e.g. steroid, remdesivir, and/or tocilizumab) was established. This allowed us to investigate the sex-mortality association in a homogeneous population that is unlikely to be influenced by any possible sex difference in vaccination rate or response, or in medication use or efficacy. Third, given the observational nature of the study design it was not possible to reliably investigate whether the dose and/or type of immunosuppressant influenced the sex-mortality relationship among kidney transplant recipients. Fourth, because reporting was voluntary, the included patients may not be completely representative of the overall population of KFRT patients with COVID-19. However, it should be noted that COVID-19 case-fatality rates and relative risk of mortality among men (vs. women) among dialysis patients in our study are comparable to those reported in KFRT registry studies that include non-selected populations, but lack detailed information for adjustment as we have in our study9.

In conclusion, among patients on KFRT with COVID-19, the male sex is not a risk factor for mortality in kidney transplant recipients but remains a risk factor in dialysis patients. The use of immunosuppressants in kidney transplant recipients, among other factors, may have narrowed the difference in the immune response to COVID-19 between men and women, and therefore reduced the sex difference in the risk of COVID-19 mortality.

Data availability

The dataset analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Peckham, H. et al. Male sex identified by global COVID-19 meta-analysis as a risk factor for death and ITU admission. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 6317 (2020).

Takahashi, T. et al. Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID-19 disease outcomes. Nature 588(7837), 315–320 (2020).

Cravedi, P. et al. COVID-19 and kidney transplantation: Results from the TANGO International Transplant Consortium. Am. J. Transplant. 20(11), 3140–3148 (2020).

Kremer, D. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients: Lessons to be learned. Am. J. Transplant. 21(12), 3936–3945 (2021).

Vinson, A. J. et al. Sex and organ-specific risk of major adverse renal or cardiac events in solid organ transplant recipients with COVID-19. Am. J. Transplant. 22(1), 245–259 (2022).

Haarhaus, M. et al. Risk prediction of COVID-19 incidence and mortality in a large multi-national hemodialysis cohort: Implications for management of the pandemic in outpatient hemodialysis settings. Clin. Kidney J. 14(3), 805–813 (2021).

De Meester, J. et al. Incidence, characteristics, and outcome of COVID-19 in adults on kidney replacement therapy: A Regionwide Registry Study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32(2), 385–396 (2021).

Salerno, S. et al. COVID-19 risk factors and mortality outcomes among medicare patients receiving long-term dialysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 4(11), e2135379 (2021).

Jager, K. J. et al. Results from the ERA-EDTA Registry indicate a high mortality due to COVID-19 in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients across Europe. Kidney Int. 98(6), 1540–1548 (2020).

Caughey, A. B. et al. USPSTF approach to addressing sex and gender when making recommendations for clinical preventive services. JAMA 326(19), 1953–1961 (2021).

Noordzij, M. et al. ERACODA: The European database collecting clinical information of patients on kidney replacement therapy with COVID-19. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 35, 2023–2025 (2020).

Harris, P. A. et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 95, 103208 (2019).

Rockwood, K. et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CanMed. Assoc. J. 173, 489–495 (2005).

Nguyen, T. L. & Xie, L. Incomparability of treatment groups is often blindly ignored in randomised controlled trials—A post hoc analysis of baseline characteristic tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 130, 161–168 (2021).

Lovakov, A. & Agadullina, E. R. Empirically derived guidelines for effect size interpretation in social psychology. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 3, 485–504 (2021).

Mauvais-Jarvis, F. et al. Sex and gender: Modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet 396(10250), 565–582 (2020).

Regitz-Zagrosek, V. Sex and gender differences in health. Science & Society Series on Sex and Science. EMBO Rep. 13(7), 596–603 (2012).

Spagnolo, P. A., Manson, J. E. & Joffe, H. Sex and gender differences in health: What the COVID-19 pandemic can teach us. Ann. Intern. Med. 173(5), 385–386 (2020).

Williamson, E. J. et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584(7821), 430–436 (2020).

Goffin, E. et al. COVID-19-related mortality in kidney transplant and haemodialysis patients: A comparative, prospective registry-based study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 36(11), 2094–2105 (2021).

Quandelacy, T. M., Viboud, C., Charu, V., Lipsitch, M. & Goldstein, E. Age- and sex-related risk factors for influenza-associated mortality in the United States between 1997–2007. Am. J. Epidemiol. 179(2), 156–167 (2014).

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7012a5.htm (Accessed 21 May 2022).

Chen, L., Han, X., Li, Y., Zhang, C. & Xing, X. The severity and risk factors for mortality in immunocompromised adult patients hospitalized with influenza-related pneumonia. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 20(1), 55 (2021).

Hilbrands, L. B. et al. COVID-19-related mortality in kidney transplant and dialysis patients: results of the ERACODA collaboration. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 35(11), 1973–1983 (2020).

Bhopal, S. S. & Bhopal, R. Sex differential in COVID-19 mortality varies markedly by age. Lancet 396(10250), 532–533 (2020).

https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants (Accessed 5 Oct 2022).

Acknowledgements

The ERACODA collaboration is an initiative to study prognosis and risk factors for mortality due to COVID-19 in patients with a kidney transplant or on dialysis that is endorsed by the ERA-EDTA. ERACODA is an acronym for European Renal Association COVID-19 Database. The organizational structure contains a Working Group assisted by a Management Team and an Advisory Board. The ERACODA Working Group members: Franssen CFM, Gansevoort RT (coordinator), Hemmelder MH, Hilbrands LB and Jager KJ. The ERACODA Management Team members: Duivenvoorden R, Noordzij M and Vart P. The ERACODA Advisory Board members: Abramowicz D, Basile C, Covic A, Crespo M, Massy ZA, Mitra S, Petridou E, Sanchez JE, White C. We thank all people that entered information in the ERACODA database for their participation, and especially all healthcare workers that have taken care of the included COVID-19 patients. The abstract of this manuscript was presented at the European Renal Association Conference 2022 and has been published in the Nephrology, Dialysis, and Transplantation journal (https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfac095.003). The manuscript has not been submitted for consideration elsewhere.

Funding

Unrestricted research grants were obtained from the European Renal Association, The Dutch Kidney Foundation, Baxter, and Sandoz. Neither organization had any role in the design of the study, interpretation of results, nor in writing of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors contributed to the data collection, study design, data analysis, interpretation, and drafting of this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vart, P., Duivenvoorden, R., Adema, A. et al. Sex differences in COVID-19 mortality risk in patients on kidney function replacement therapy. Sci Rep 12, 17978 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22657-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22657-4

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.