Abstract

While previous rheumatoid arthritis (RA) studies have focussed on cardiometabolic and lifestyle factors, less research has focussed on psychological variables including mood and cognitive health, and sleep. Cross-sectional analyses tested for associations between RA and RF+ (positive rheumatoid factor) vs. mental health (depression, anxiety, neuroticism), sleep variables and cognition scores in UK Biobank (total n = 484,064). Those RF+ were more likely to report longer sleep duration (β = 0.01, SE = 0.004, p < 0.01) and less likely to get up in the morning easily (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.92–0.99, p = 0.01). Those reporting RA were more likely to score higher for neuroticism (β = 0.05, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001), to nap during the day (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.06–1.14, p < 0.001), have insomnia (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.22–1.35, p < 0.001), have slower reaction times (β = 0.02, SE = 0.008, p < 0.005) and score less for fluid intelligence (β = − 0.03, SE = 0.01, p < 0.05) and less likely to get up easily (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.58–0.64, p < 0.001). The current study suggests that prevalent RA, and RF+ status are associated with differences in mental health, sleep, and cognition, highlighting the importance of addressing these aspects in clinical settings and future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the most prevalent chronic inflammatory condition affecting the joints1, is characterized by pain, stiffness and swelling, which if not controlled, can lead to permanent damage. The estimated prevalence for RA in UK adults is around 0.81%, with a higher prevalence for women (1.16%) than for men (0.44%)2. Rheumatoid factor (RF) is an autoantibody that is present in approximately 80% of people with RA and can occur years before any clinical symptoms3. It can lead to worse outcomes, including higher disease activity and radiographic progression4,5. However, it can also be present in the general population6 including with multimorbidity7. If left untreated, RA can result in several negative outcomes including increased mortality, hospitalization, work disability and decreased quality of life8. RA can also be associated with other comorbidities, most notably cardiovascular disease9, mental health, sleep and cognitive problems.

Mental health

Patients with RA are more likely to suffer from depression, even after controlling for age and sex10. Prevalence rates for depression in research studies vary considerably and can range between 0.04 and 66.3% depending on the instrument used for diagnosis11. The overall quality of published papers is also poor, with a median quality score of 3/10 and 82% of papers scoring 5/10 or lower11. An important issue with depression research in RA is that the two disorders share several symptoms such as fatigue and sleep disturbance that can often be excluded from analyses12 resulting in an underestimation of true prevalence rates. Nevertheless, even when the gold standard of diagnostic criteria for depression is used (i.e. DSM diagnostic criteria) prevalence rates for depression in RA are still high (16.8%)11 compared to prevalence estimates for the general population (4.1% for 1-year estimates and 6.7% for lifetime prevalence)13. Anxiety in RA has received considerably less attention but prevalence rates between 13.5 and 70% have been reported14,15,16. Also, a high neuroticism score at baseline was significantly associated (p < 0.01) with depression and anxiety at the 3 and 5-year follow up in RA patients, making it the most consistent and effective predictor of mental health in the study17. While Isik et al.16 reported no significant differences in anxiety and depression between RF+ and RF− groups, in another study people that were RF− spent twice as much time being treated for depression and were more likely to need longer depression treatment as a result of a prolonged diagnosis delay18. Ho et al.19 reported RF to be a significant predictor for severity of depression even after adjusting for confounding factors, while for anxiety, RF was a significant predictor only in the univariate analysis.

Sleep

Poor sleep in RA is estimated to be present in at least 49% of patient cohorts, with many studies reporting figures as high as 80% for the RA subsample20,21,22,23. Zhang et al.24 undertook the first meta-analysis (n = 1143) evaluating poor sleep in RA as measured by the PSQI (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) and suggested that RA patients scored higher (indicative of worse sleep) than the healthy control group in every domain of the questionnaire (i.e. subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, presence of sleep disorders, use of sleeping medication and daytime dysfunction as a consequence of poor sleep) and total PSQI score. When comparing between poor sleepers with RA and good sleepers with RA, poor sleepers are more likely to have higher disease activity scores, worse night pain and total pain and higher rates for depression and anxiety, while the good sleep RA subsample reported using a significantly higher percentage of synthetic DMARDs (Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs)22. In contrast, RF status did not significantly differ between poor and good sleepers21,22.

Cognition

A recent systematic review including 15 papers and 749 participants has suggested that the RA patient-population might show cognitive differences that could warrant attention in clinical and research settings, but more studies are needed to better understand prevalence rates and what specific cognitive domains are impaired25. RA patients either had worse performances than healthy controls on average or performed at a level that was below their age-related norms. Considering that some of the studies included also had other comparison clinical groups (i.e. fibromyalgia, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome) that also had worse performances at cognitive tasks, the authors suggest that cognitive impairment may be present in other chronic, inflammatory or autoimmune conditions involving pain. Cognitive impairment on a range of cognitive tests ranged from 8% in the semantic fluency test (recall test) to 29% in the design fluency test, with 30% of RA patients displaying impairment in four or more tests (n = 122, mean age = 58.4 ± 10.8)26. In the multivariable analyses, use of glucocorticoids and cumulative number of cardiovascular disease (CVD) factors were independently associated with cognitive impairment in this patient population. Regarding individual components of cognition, Vitturi et al.27 observed significantly worse performance (p < 0.001) in RA for the attention, remote memory, repetition, stage command, writing, read and obey and copy tasks. Those using biologics were less likely to be classified as cognitively impaired using the MMSE (Mini-mental state examination) (p = 0.05), while those under glucocorticoids and that were RF+ were more likely to be classified as cognitively impaired, according to the MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) (p = 0.01 and = 0.05 respectively).

Despite being important contributors to quality of life, sleep, mental health, and cognition have been largely neglected in the RA literature. Most studies to date had a sample size of under 1000 people and use different instruments to test these associations, without properly controlling for covariates. As the systematic review carried out by Matcham et al.11 pointed out there were even 40 different ways to define depression as well as to measure it leading to different prevalence rates and an overall poor quality of published papers. Similarly, there is a lack of understanding and a huge gap in the literature about the role of rheumatoid factor positivity (RF+) on these domains. We aim to provide a solution to these problems by using a very large population cohort of around 500,000 participants all measured identically, by looking at both self-reported rheumatoid arthritis and rheumatoid factor and by controlling for a wide range of covariates. In conclusion, the aim of the current study was to characterize mental health, cognition, and sleep variables in people with RA and to compare these associations in people with positive RF (RF+) and negative RF (RF−) in a large population cohort.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The current study used the UK Biobank, a large database that contains an extensive range of health measures for around half a million participants in the UK. People aged between 40 and 69 years old that were registered with the National Health Service (NHS) and lived up to approximately 25 miles from one of the 22 UK Biobank assessment centers were invited to take part28. Around 5.47% agreed-equivalent to around 500,000 participants- and recruitment took place between 2006 and 2010. All volunteers gave informed consent, and the study was conducted under generic approval from the NHS National Research Ethics Service (approval letter dated 17th June 2021, Ref 11/NW/0382) and under UK Biobank project approval 17689 (PI Lyall). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, informed consent was collected from every participant and the data was anonymized. At the baseline visit at the assessment centre participants completed touchscreen questionnaires on their sociodemographic factors (such as age, sex, ethnicity, postcode of residence), lifestyle (e.g. smoking status, alcohol intake), medical history (including mental health and musculoskeletal problems) and had several physical measures taken and samples of blood, saliva and urine collected28. Area-based socioeconomic deprivation was measured using Townsend scores derived from postcode of residence29. In the current study RA, depression, anxiety and cardiometabolic diseases are based on self-report.

All UK Biobank participants had biomarker levels measured at baseline from serum and packed red blood cell samples. For the current study, very low levels of rheumatoid factor that were coded as ‘missing’ in the original data were recoded conservatively as the square root of the minimum stated detectable value if participants had data for a remaining biomarker30. A new binary variable was then computed for rheumatoid factor category with variables over 14 IU/ml considered rheumatoid factor positive (RF+)31. We removed those that failed biomarker quality control (coded as ‘no data returned’ or logged as having unrecoverable aliquot problems). Details about biomarker quality control, measurements and analysis methods can be found at:

https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/showcase/docs/haematology.pdf,

https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/showcase/docs/serum_biochemistry.pdf, and

https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/showcase/docs/biomarker_issues.pdf.

At the assessment centre, five cognitive tests were administered to participants via a touchscreen computer. It took approximately 15 min to complete all tests (numeric memory excluded in the present study due to low completion rates32. For reaction time (N = 496,771), mean response time (milliseconds) was recorded to matching pairs of visual stimuli. The fluid intelligence/verbal-numeric reasoning touchscreen assessment (N = 209,473) was comprised of questions designed to assess the capacity to solve problems that require logic and reasoning ability, independent of acquired knowledge. Prospective memory (N = 216,124) tested the ability for the participant to remember and follow instructions given before a task. The data used for the present analyses was dichotomized as correctly recalled on first attempt or not. The pairs matching task (N = 498,748) assessed visuo-spatial memory. For this paper, the used variable was the number of errors made.

At the assessment centre participants also completed touchscreen questionnaires about their lifestyle and environment, including mental health (depression, anxiety, derived summary score of neuroticism based on 12 neurotic behaviour domains) and sleep variables such as sleep duration (h/day), frequency of napping during the day (ordinal with 4 options), ease of getting up in the morning (ordinal with 6 options) and insomnia frequency (ordinal with 4 options). Multi-level ordinal variables were dichotomized for the current study: ever nap during the day (No/Yes), ease of getting up in the morning (Not easy/Easy) and insomnia (No/Yes).

Statistical analyses

We used baseline data from the UK Biobank cohort (n = 502,506) to cross-sectionally compare people with and without RA, and people that are RF+ versus RF− on a variety of sociodemographic, lifestyle, illness-related factors and mental health, performance on cognitive tests and sleep-related factors33. We performed logistic and linear regression analyses to determine whether RF+ status (i.e. seropositivity) or RA diagnosis were associated with mental health, cognition, and sleep variables. More specifically, we performed linear regression models for the neuroticism, sleep duration, reaction time, fluid intelligence and pairs matching variables and logistic regressions for the depression, anxiety, nap during the day, getting up in the morning, insomnia, and prospective memory variables. We adjusted for the covariates of age, sex, self-reported ethnicity, deprivation index, smoking status, BMI and alcohol intake (frequency). We removed those that were advised by their doctor to stop drinking alcohol and recorded those with a BMI under 18 as missing. For sleep analyses we also controlled for cardiometabolic diseases.

Results

Demographics

Of the approximately 500,000 baseline UK Biobank participants, 5722 (1.18%) self-reported having RA and 25, 772 (5%) were RF+ (see Table 1). Out of those that self-reported RA 74% were RF− and 26% were RF+. For the current study we have split the baseline sample between self-report RA and non-RA and RF+ versus RF− to compare any differences between these subsamples. Participants that reported RA were older and more likely to be female (69% of RA patients compared to 31% for males). The RA subsample was more likely to report being a current or previous smoker but more likely to drink alcohol less frequently. They were also more likely to have higher values for BMI, hip circumference, and waist circumference. Participants with RF+ were also older and more likely to be female (56% compared to 44% males). There were also significant differences between RF− and RF+ for ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol intake, deprivation index and physical activity score.

Associations

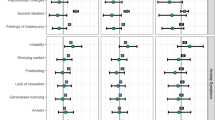

Mental health

In the unadjusted regression models, people RF+ were more likely to score less for neuroticism (β = − 0.01, SE = 0.005, p < 0.001) (see Supplementary Table S2), while people that reported RA were more likely to have depression (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.08–1.25, p < 0.001) and score higher for neuroticism (β = 0.08, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001) (see Table 2). After adjusting for covariates, those that reported RA were still more likely to score high for neuroticism (β = 0.05, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001) but less likely to report anxiety (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.67–0.95, p < 0.01).

Sleep

Regarding sleep, those RF+ were more likely to report longer sleep durations (β = 0.01, SE = 0.004, p < 0.001), more likely to nap during the day (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03–1.09, p < 0.001), and more likely to have insomnia (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.03–1.10, p < 0.001) (see Supplementary Table S3) while those that self-reported RA were more likely to nap during the day (OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.17–1.26, p < 0.001), less likely to get up in the morning with ease (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.59–0.63, p < 0.001) and more likely to have insomnia (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.41–1.56, p < 0.001) (see Table 3). After adjusting for covariates, those RF+ were more likely to report longer sleep duration (β = 0.01, SE = 0.004, p < 0.01) and less likely to get up in the morning easily (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.92–0.99, p = 0.01). Those self-reporting having RA were more likely to nap during the day (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.06–1.14, p < 0.001), less likely to get up with ease (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.58–0.64, p < 0.001) and more likely to suffer from insomnia (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.22–1.35, p < 0.001).

Cognition

For cognition, those RF+ were more likely to score higher for reaction time (β = 0.03, SE = 0.004, p < 0.001) (see Supplementary Table S4). Those that self-reported having RA were also more likely to score higher for reaction time (β = 0.13, SE = 0.009, p < 0.001), but more likely to score less for fluid intelligence (β = − 0.10, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001) and less likely to perform well on the prospective memory task (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.81–0.94, p < 0.001) (see Table 4). After adjusting for covariates, reaction time (β = 0.02, SE = 0.008, p < 0.005) and fluid intelligence (β = − 0.03, SE = 0.01, p < 0.05) remained significant predictors for RA.

Discussion

The prevalence of self-report RA within the UK Biobank baseline sample was 1.18%, out of which 69% were female and 31% were males. This is similar to other estimates in the literature that suggest around 0.81% of people in the UK suffer from RA, with a higher prevalence for women than men2. Out of the 5722 participants that reported RA, 74% were RF− and 26% were RF+. This was much lower than previous estimates of 80%3 and it could be due to differences in measurement, measurement error or changes in RF levels compared to previous population recorded values. RA patients were more likely to report being a current or previous smoker, in line with previous literature suggesting smoking is a risk factor for developing RA34. There were also significant differences between RF+ and RF− people regarding smoking as Sugiyama et al.34 suggested that odds of having RA are almost double for RF+ male smokers. The RA subsample was more likely to drink alcohol less frequently. Observational studies often suggest a ‘protective’ effect of alcohol for RA but this can be due to confounding recall bias35. It is possible that those with more severe RA drink less alcohol or that those that completely abstain from drinking do so due to medical reasons and are less healthy overall compared to those that drink occasionally. Indeed, Mendelian randomization analyses generally do not support the inverse causal relationship between alcohol and RA36. The RA subsample was also more likely to have higher values for BMI, hip circumference, and waist circumference. Having a BMI over 30 was associated in the literature with an increased risk of developing RA (RR = 1.25, 95% CI 1.07–145)37 and 40% lower odds of achieving remission38. To our knowledge there is a gap in the literature comparing people RF− and RF+ but we found significant differences for age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, alcohol intake, deprivation, and physical activity score (but not BMI).

Among RA comorbidities, cardiovascular-related disease was studied most extensively as it is believed that RA patients have a 50% increased risk of CVD-related mortality compared to the general population (meta-SMR 1.50, 95% CI 1.39–1.61). Even after accounting for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, there is still a large proportion of heart failure (at the age of 80) left unexplained in RA patients (p < 0.01)39. The RA subsample in the current study was also more likely to report diabetes, hypertension, heart attack and stroke, while RF+ people were more likely to report hypertension, heart attack and stroke (see Supplementary Table S1).

Regarding mental health, there were significant differences between RA and non-RA groups on average, and RF+ vs RF− for depression and neuroticism. The prevalence rate for depression in RA was 6.9% and for anxiety was 1.1% (see Supplementary Table S1). Prevalence rates for depression in the literature can range between 0.04 and 66.3% depending on the instrument used for diagnosis11. The current study was limited to using self-report depression and anxiety. After adjusting for covariates, RA people were more likely to score higher for neuroticism and less likely to report anxiety. RA was associated with higher neuroticism in our analyses, even after adjusting for covariates. This can be essential for mental health in RA as Evers et al.17 suggested neuroticism is the most consistent and effective predictor of mental health issues in RA at the 3 and 5 years follow up. Regarding sleep, previous studies estimated that between 49 and 80% of RA patients report poor sleep20,21,22,23. In our study, those RF+ were more likely to report longer sleep duration and less likely to get up in the morning with ease, even after adjusting for covariates. Those that reported having RA were more likely to nap during the day, less likely to get up with ease in the morning and more likely to suffer from insomnia even after adjusting for covariates. For cognition, a systematic review suggested that people with RA might have cognitive impairment but more research is needed to better understand what specific domains are affected25. In our study, RF+ people were more likely to score higher for reaction time only in the unadjusted regression analyses. In the unadjusted regressions those that reported having RA were more likely to score higher for reaction time and less for the fluid intelligence and the prospective memory tasks. After adjusting for covariates, reaction time and fluid intelligence remained significant predictors. Considering that RA is a disease that can cause joint stiffness and pain, we believe a reaction time task can be severely impacted by this, unveiling a problem with mobility rather than cognition.

The UK Biobank has the advantage of being a relatively large cohort with around half a million people recruited, tested, and measured in the same way. However, it might not be representative of the population for lifestyle risk factors and disease, and even age or deprivation; there is a well-established ‘healthy bias’ and some evidence this may meaningfully and significantly bias analyses towards type 1/2 errors40,41. It is possible that those with less severe RA or mental health take part in research studies. The current study was also limited to using self-report illness (e.g., depression, anxiety, and rheumatoid arthritis). As in a previous study by Siebert et al.42 this meant that we could not differentiate between participants that preferred not to report or did not remember their diseases, and those that were actually healthy and hence had nothing to report. However, our self-report RA prevalence was similar to previous estimates. Generally, choosing not to answer queries was relatively rare in UK Biobank at < 5%. We believe that the ‘getting up in the morning’ question should have been phrased differently as it does not differentiate between difficulties waking up and difficulties getting out of bed. People with RA suffer from joint stiffness, especially in the morning which could make it more difficult for them to get out of bed. Similarly, we observed an association with RF+ and poorer sleep; the exact mediating mechanisms underlying this are unclear. Future research, may investigate the possibility that joint deformities, higher chronic pain and other comorbidities may contribute to the observed associations. In our study, those RF+ were more likely to report longer sleep duration and more likely to have insomnia which may appear contradictory. The UK Biobank insomnia question was based on self-report and asked participants to include naps as well. We believe that naps should have been excluded from this question as they can give the impression of a long sleep duration at night when in fact quite the opposite could be true—a person could suffer from insomnia which would make them more likely to need a nap throughout the day. Future research should also investigate this further based on more objective sleep measures.

The cross-sectional nature of the current study means that we could not establish causal relationships and rule out confounding and reverse causation. It is unclear whether mental health, sleep and cognition predate or are caused by RA. By only using a single measurement of RF we were also unable to investigate whether levels fluctuate over time or whether they are stable. Future research could benefit from using primary care and hospital admissions diagnoses and genetic or longitudinal analyses for causal relationships.

Despite being important areas of RA patients’ overall quality of life, mental health, sleep and cognition are often overlooked in the literature and in the clinic. Similarly, we need a better understanding about the role RF plays on these domains. The current study suggests that self-reported RA and RF status are associated with differences in all three domains and provide substantial support to previous literature, highlighting the importance of addressing these aspects in clinical settings and future research.

Data availability

Data is available from the UK Biobank website for a fee via their data access procedure: https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research/register.

References

Symmons, D. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis: Determinants of onset, persistence and outcome. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 16, 707–722 (2002).

Symmons, D. et al. The Prevalence of Rheumatoid Arthritis in the United Kingdom: New Estimates for a New Century (2002).

Nell, V. P. K. et al. Autoantibody profiling as early diagnostic and prognostic tool for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64, 1731–1736 (2005).

Aletaha, D., Alasti, F. & Smolen, J. S. Rheumatoid factor determines structural progression of rheumatoid arthritis dependent and independent of disease activity. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72, 875–880 (2013).

Scott, D. L., Coulton, B. L., Symmons, D. P. M. & Popert, A. J. Long-term outcome of treating rheumatoid arthritis: Results after 20 years. Lancet 329, 1108–1111 (1987).

Van Schaardenburg, D., Lagaay, A. M., Otten, H. G. & Breedveld, F. C. The relation between class-specific serum rheumatoid factors and age in the general population. Rheumatology 32, 546–549 (1993).

Newkirk, M. M. Rheumatoid factors: Host resistance or autoimmunity?. Clin. Immunol. 104, 1–13 (2002).

Michaud, K. & Wolfe, F. Comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 21, 885–906 (2007).

Aviña-Zubieta, J. A. et al. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Care Res. 59, 1690–1697 (2008).

Dickens, C., McGowan, L., Clark-Carter, D. & Creed, F. Depression in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychosom. Med. 64, 52–60 (2002).

Matcham, F., Rayner, L., Steer, S. & Hotopf, M. The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol. (United Kingdom) 52, 2136–2148 (2013).

Nerurkar, L., Siebert, S., McInnes, I. B. & Cavanagh, J. Rheumatoid arthritis and depression: An inflammatory perspective. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 164–173 (2019).

Waraich, P., Goldner, E. M., Somers, J. M. & Hsu, L. Prevalence and incidence studies of mood disorders: A systematic review of the literature. Can. J. Psychiatr. 49, 124–138 (2004).

Covic, T. et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Prevalence rates based on a comparison of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) and the hospital, Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). BMC Psychiatry 12, 6 (2012).

El-Miedany, Y. M. & El Rasheed, A. H. Is anxiety a more common disorder than depression in rheumatoid arthritis?. Jt. Bone Spine 69, 300–306 (2002).

Isik, A., Koca, S. S., Ozturk, A. & Mermi, O. Anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 26, 872–878 (2007).

Evers, A. W. M., Kraaimaat, F. W., Geenen, R., Jacobs, J. W. G. & Bijlsma, J. W. J. Longterm predictors of anxiety and depressed mood in early rheumatoid arthritis: A 3 and 5 year followup. J. Rheumatol. 29, 2327–2336 (2002).

Tillmann, T., Krishnadas, R., Cavanagh, J. & Petrides, K. V. Possible rheumatoid arthritis subtypes in terms of rheumatoid factor, depression, diagnostic delay and emotional expression: An exploratory case-control study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 15, 25 (2013).

Ho, R. C. M., Fu, E. H. Y., Chua, A. N. C., Cheak, A. A. C. & Mak, A. Clinical and psychosocial factors associated with depression and anxiety in Singaporean patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 14, 37–47 (2011).

Durcan, L., Wilson, F. & Cunnane, G. The effect of exercise on sleep and fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized controlled study. J. Rheumatol. 41, 1966–1973 (2014).

Goes, A. C. J., Reis, L. A. B., Silva, M. B. G., Kahlow, B. S. & Skare, T. L. Rheumatoid arthritis and sleep quality. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. (English Ed.) 57, 294–298 (2017).

Guo, G. et al. Sleep quality in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Contributing factors and effects on health-related quality of life. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 14, 25 (2016).

Devins, G. M. et al. Restless sleep, illness intrusiveness, and depressive symptoms in three chronic illness conditions: Rheumatoid arthritis, end-stage renal disease, and multiple sclerosis. J. Psychosom. Res. 37, 163–170 (1993).

Zhang, L., Shen, B. & Liu, S. Rheumatoid arthritis is associated with negatively variable impacts on domains of sleep disturbances: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Health Med. 20, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1764597 (2020).

Meade, T., Manolios, N., Cumming, S. R., Conaghan, P. G. & Katz, P. Cognitive impairment in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 70, 39–52 (2018).

Shin, S. Y., Julian, L. & Katz, P. The relationship between cognitive function and physical function in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 40, 236–243 (2013).

Vitturi, B. K., Nascimento, B. A. C., Alves, B. R., de Campos, F. S. C. & Torigoe, D. Y. Cognitive impairment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Clin. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2019.08.027 (2019).

Allen, N. et al. UK Biobank: Current status and what it means for epidemiology. Heal. Policy Technol. 1, 123–126 (2012).

Townsend, P. Deprivation. Health Visit. 45, 223–224 (1972).

Ferguson, A. C. et al. Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility gene apolipoprotein e (APOE) and blood biomarkers in UK biobank (N=395,769). J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 76, 1541–1551 (2020).

Sunar, İ & Ataman, Ş. Serum c-reactive protein/albumin ratio in rheumatoid arthritis and its relationship with disease activity, physical function, and quality of life. Arch. Rheumatol. 35, 247–253 (2020).

Lyall, D. M. et al. Cognitive test scores in UK biobank: Data reduction in 480,416 participants and longitudinal stability in 20,346 participants. PLoS One 11, 25 (2016).

Stanciu, I., Siebert, S., Mackay, D. & Lyall, D. OP0215 Mental health, sleep and cognition characteristics in rheumatoid arthritis and associations with rheumatoid factor status in the UK biobank. Ann. Rheumat. Diseases 80, 122–129 (2021).

Sugiyama, D. et al. Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 70–81 (2010).

Scott, I. C. et al. The protective effect of alcohol on developing rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (United Kingdom) 52, 856–867 (2013).

Bae, S.-C. & Lee, Y. H. Alcohol intake and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A Mendelian randomization study. Z. Rheumatol. 78, 791–796 (2018).

Qin, B. et al. Body mass index and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17, 1–12 (2015).

Liu, Y., Hazlewood, G. S., Kaplan, G. G., Eksteen, B. & Barnabe, C. Impact of obesity on remission and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 69, 157–165 (2017).

Crowson, C. S. et al. How much of the increased incidence of heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis is attributable to traditional cardiovascular risk factors and ischemic heart disease?. Arthritis Rheum. 52, 3039–3044 (2005).

Keyes, K. M. & Westreich, D. UK Biobank, big data, and the consequences of non-representativeness. Lancet 393, 1297 (2019).

Lyall, D. et al. Quantifying bias in psychological and physical health in the UK Biobank imaging sub-sample. PsyArXiv 20, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.31234/OSF.IO/UPVB9 (2021).

Siebert, S. et al. Characteristics of rheumatoid arthritis and its association with major comorbid conditions: Cross-sectional study of 502 649 UK Biobank participants. RMD Open 2, e000267 (2016).

Funding

This work was supported by The Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences (MVLS) Doctoral Training Programme (DTP) scholarship from the University of Glasgow. No other specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception: I.S., D.M.L., D.M.K., S.S. Analysis: I.S. Writing of the manuscript: I.S. Critical revision: all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stanciu, I., Anderson, J., Siebert, S. et al. Associations of rheumatoid arthritis and rheumatoid factor with mental health, sleep and cognition characteristics in the UK Biobank. Sci Rep 12, 19844 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22021-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22021-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.