Abstract

Academic dishonesty is becoming a big concern for the education systems worldwide. Despite much research on the factors associated with academic dishonesty and the methods to alleviate it, it remains a common problem at the university level. In the current study, we conducted a survey to link personality traits (using the HEXACO model) and people’s general attitudes towards the rule (i.e., “rule conditionality” and “perceived obligation to obey the law/rule”) to academic dishonesty among 370 university students. Using correlational analysis and structural equation modeling, the results indicated that both personality traits and attitudes towards the rule significantly predicted academic misconduct. The findings have important implications for researchers and university educators in dealing with academic misconduct.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Academic dishonesty is a global issue that attracts much attention from educators worldwide, and relevant research could date back to the last century1. It is considered immoral and inappropriate because the behavior has an unfair advantage over other students and impedes individuals’ capacity to study2,3. Dishonesty behavior often starts early in school, such as copying others’ work, and has been a consistent and paramount problem throughout all education levels4. It is an educational and academic issue with severe consequences5. Engagement in academic dishonesty predicts increased acceptance of immoral workplace behavior, indicating its continuous influence post-graduation6,7. At the university level, such misconduct behavior has clear potential to diminish the reputation and integrity of universities. It hinders universities’ ability to ensure that students who achieve degrees have the knowledge and skills they require for employment or further study8.

Much literature on the individual predictors of academic cheating has mostly focused on the influences of personality traits, academic attitudes & values, and some demographic variables9. Several personality traits were found to be significantly predictive, such as impulsivity10, psychopathy11, Machiavellianism and narcissism12. Self-control may explain why people do, or do not, engage in plagiarism when the opportunity is available13. Curtis et al.14 found that self-control and academic misconduct were negatively correlated. Although individuals’ self-control can vary depending on situational factors such as mood, fatigue, and hunger, it is more like stable personality-like differences15.

Research on the demographic variables found that age and gender are critical factors predicting academic misconduct. For instance, as they age, female college students are less likely to engage in academic dishonesty due to fewer comparisons between one’s own behaviors and peer behaviors16. However, age and gender are not consistently found to be significant factors in most research on academic misconduct9,17.

In the current study, we still focused on these individual factors with attempts to 1) assess a recent model of personality (i.e., HEXACO) and its predictive power of academic dishonesty; and 2) to link people’s general attitude towards the rule/law to academic dishonesty, considering that it is essentially a violation of the rules in academia. Age and gender effects are examined along with the above goals.

Academic dishonesty

Academic dishonesty, academic misconduct, academic cheating, and academic integrity are concepts often used interchangeably in previous literature. The concept is usually defined through behavioral classifications. Pavela18 considered academic dishonesty to contain four main types of misconduct that deliberately violate school regulations: cheating, fabrication, facilitation, and plagiarism. McCabe and Trevino19 further expanded the scope of this concept into 12 types of violating behaviors in school, including sneaking at notes in the exam, copying others’ answers in the exam, copying others’ answers without their permission in the exam, etc. These researchers developed a 12-item scale to measure academic dishonesty, which is widely used19,20. However, Adesile and Nordin21 criticized that the psychometric properties have not been critically investigated despite their broader literature application. To validate the psychometric properties of the instrument and determine the dimensionality of academic dishonesty, Adesile21 adapted the original scale, divided academic dishonesty into three dimensions (“cheating,” “plagiarism,” and “research misconduct”), and named it “the academic integrity survey.”

Academic dishonesty is found to be largely explained by individual factors22. Motivation is one of the major individual factors relating to academic dishonesty. Through a meta-analytic investigation, Krou and colleagues23 reviewed 79 studies and reported that academic dishonesty was negatively associated with intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, utility value, and internal locus of control, and was positively associated with amotivation and extrinsic goal orientation. Motivation, however, may vary across different cultural backgrounds. A recent study of Chinese university students found that their unethical academic behaviors are associated with their unique motivation to meet parents’ expectations24.

Morality is another crucial predictor of academic cheating and plagiarism. Individuals with a high level of morality, emphasis on fairness, and value of social rules have stringent attitudes towards plagiarism25,26,27. Meanwhile, moral disengagement is positively associated with cheating28. The predicting effect of morality may also be inconsistent across cultures. Ampuni et al.29 studied the relationship between academic dishonesty and the five moral foundations in Indonesia, and found only a weak predictive power of the “authority” foundation on academic dishonesty.

Since the COVID-19 epidemic outbreak, courses and examinations have been conducted online, and researchers are concerned that academic misconduct in online learning environments has become more serious30. Studies, however, provided little and even opposite evidence regarding the actual behavioral differences in academic misconduct between traditional and online settings. Peled et al.31 found that students tend to engage less in academic dishonesty behaviors online than in face-to-face courses. In addition, cheating intentions among students in traditional and online education settings are very little32. To reconcile the inconsistent findings, researchers started considering potential moderating and mediating factors such as the types of academic dishonesty, the level of technology complexity, and statistics anxiety33,34,35.

Personality traits and academic dishonesty

Personality reflects a person’s consistent patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. It has a large effect on individuals’ academic behaviors. The Big Five personality model is the most widely used predictor of academic dishonesty. For instance, Giluk and Postlethwaite36 reviewed studies of both high school and university students, and concluded that conscientiousness and agreeableness (of the Big Five) are the strongest predictors of academic dishonesty. Graziano and Eisenberg37 found agreeable people more trusting and less cynical. As a result, they were less likely to justify cheating and see it as a necessity to compete with others. Lee et al.9 conducted a meta-analysis on predictors of academic dishonesty and confirmed the strong relationship between agreeableness and academic dishonesty. They also found openness to be associated with self-efficacy/personal ability, and in turn, was negatively related to academic dishonesty. Finally, a positive association between neuroticism and academic procrastination increased cheating behaviors at school38.

Empirical evidence on the relationship between extraversion and academic dishonesty, however, is not consistent. For example, some research found a small positive association between extraversion and scholastic dishonesty11, while others indicated a moderate negative association39, and nonsignificant findings36.

Ashton and Lee40 extended the Big Five personality model with a set of lexical studies, and developed a six-dimension model, referred to as the HEXACO model of personality structure. The name of this model reflects both the number of factors (i.e., the Greek hexa, six) and their names: Honesty-Humility (H), Emotionality (E), extraversion (X), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), and Openness to Experience (O). It is essential the Big Five personality plus an additional Honesty-Humility dimension. The six-dimensional structure was more replicable across cultures than the Big Five model, as the Big Five structure has failed to present in four languages that recovered the HEXACO dimensions41. It has become a major tool in measuring personality traits in the early 21st century.

The HEXACO model, particularly the Honesty-Humility (H) dimension, is proven to be very useful in predicting many unethical behaviors. Kleinlogel et al.42 investigated the relationship between Honesty-Humility and cheating behavior. Results showed that individuals high in Honesty-Humility were less likely to cheat than those low on this trait. Honesty-Humility was negatively associated with adolescents’ unethical behavior, and moral disengagement partially mediated this negative association43. Hilbig and Zettler44 found that German adults who were low in Honesty-Humility were more likely to behave dishonestly across various experimental situations (e.g., coin-toss task and dice-task). Honesty-Humility was negatively associated with unethical business decisions among people from Fiji and the Marshall Islands45. Honesty-Humility was proved to be the strongest predictor of cheating, dishonesty, counterproductive behavior, and antisocial behavior, according to a meta-analysis41. Accordingly, the current study posits that,

Hypothesis 1

All six dimensions of the HEXACO model will predict academic dishonesty. Specifically, Honesty-Humility (H), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), Openness to Experience (O), and Emotion Stability (E) are all expected to predict academic dishonesty negatively.

Attitudes towards the rule: perceived obligation of rule/law and rule conditionality

The concept of the perceived obligation of law/rule proposed (short for POOL) by Tyler46 refers to individuals’ variability in perceptions of obeying general laws. The higher the endorsement, the more likely they are to comply with laws and rules. If one’s POOL level is high, it has nothing to do with the fear of violating and thus being punished by the laws, and it is also not because someone sees other people’s compliance behaviors and tries to conform and comply. POOL exists at the personal level, which arises from people’s knowledge and conscience to stand up for the laws and rules.

Tyler’s research has shown a negative link between POOL and general criminal behavior. The more one perceives an obligation to obey the law, the less likely one will violate the law47. In other words, if one’s POOL is higher, one is not expected to perform academic misconduct, as the person would like to obey the rule or law, and volunteer to restrain one’s behavior. POOL is also found to be a key element in predicting compliance behavior to slow the spread of the virus during the COVID-19 pandemic48.

Rule conditionality (RC), also called rule orientation, assess the extent to which an individual perceives it is acceptable to violate the legal rules under certain conditions49. In other words, less rule-oriented people accept more reasonable circumstances to break the rules, and those who are more rule-oriented acknowledge fewer acceptable circumstances to violate the regulations.

RC derives from POOL and negatively relates to POOL, but they are very different. RC presents the level of flexibility when people evaluate different circumstances to break the law or rules. POOL is a sense of one’s obligation and duty to obey the laws and regulations. RC played a crucial role in predicting compliance behaviors and law violations. When laws go against personal morals, people will weigh the advantages, and disadvantages of immoral behavior, combined with moral belief, the lack of knowledge of the law, cost-benefit analysis, social norms, and lack of procedural justice are all critical roles in influencing the possibility of violating the law49.

In general, since both POOL and RC are stable personality-like variables that do not vary across mood and situations, and because misconducts in academia are rule violations by their nature (although the consequences are not similarly severe as law violations), we expect that students’ perception of the duty to obey the law/rule and their sense of rule conditionality would both be significant predictors of academic dishonesty. Accordingly, the current study expects that,

Hypothesis 2

RC positively predicted academic dishonesty, and POOL negatively predicted academic dishonesty. That is, participants who are more likely to consider rules as conditional, will report more cheating behaviors. In contrast, participants who perceive more obligation to obey the law, will report fewer cheating behaviors.

Method

The current study has been approved by the IRB of School of Philosophy and Sociology of Jilin University. Informed consent has been obtained from all participants of the present study. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Sample

The sample consists of 370 students coming from a Northern Chinese University. The mean age of the participants was 19.77 years old (SD = 3.63). 224 (60.54%) participants majored in sciences and 146 (39.46%) participants majored in humanities and social sciences. 211 (57.03%) were male students, and 159 (42.97%) were female students.

Instruments

All research instruments were originally in English, translated into Chinese by a psychology graduate student, and back-translated by a bilingual psychology researcher.

Academic dishonesty (AD)

The Academic Integrity Survey (AIS)50 was used to measure academic dishonesty (α = 0.916). It contains 15 items assessing the “Cheating,” “Research Misconduct,” and “Plagiarism” of academic misconduct. The survey comprised an 8-point Likert scale (1 = ‘very strongly disagree’; 8 = ‘very strongly agree’). A higher score on the scale indicated a higher level of academic dishonesty. The internal consistency for the whole scale in current study was 0.955, with Cronbach’s alpha being 0.919, 0.812, and 0.817 for “Cheating,” “Research Misconduct,” and “Plagiarism,” respectively.

Personality

The HEXACO model40, a six-dimension structure containing the factors Honesty-Humility (H), Emotionality (E), Extraversion (X), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), and Openness to Experience (O), was used as a measure of personality, with 60 items in total. The internal consistency reliabilities ranged from 0.77 to 0.80 in the college sample and from 0.73 to 0.80 in the community sample51. The HEXACO-60 comprised a 5-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’; 5 = ‘strongly agree’). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.795(αHH = 0.701, αEX = 0.748, αEM = 0.642, αAG = 0.649, αCO = 0.609, αOP = 0.668) in the current study.

Rule conditionality (RC)

Rule Conditionality Scale49 was utilized to indicate the extent to which individuals perceive acceptable conditions for breaking the law in general (α = 0.928). The 7-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’; 7 = ‘strongly agree’) contains 12 items, which is calculated as a mean score (M = 3.49, SD = 1.08), with higher scores indicating more rule conditionality (i.e., the individual accepts fewer justifications for violating laws). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.868 in the current study.

Perceived obligation to obey the law (POOL)

Perceived Obligation to Obey the Law47 includes six items on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’; 4 = ‘strongly agree’, α = 0.64). The POOL was calculated as a mean score of all items (M = 2.78, SD = 0.61), with a higher score indicating a higher perceived obligation to obey the law. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.671 in the current study.

Procedure

Participants were offered course credits to take part in an online study. Wenjuanxin was used as the data collection platform, providing functions equivalent to Amazon Mechanical Turk. The participants were asked to answer the AIS, HEXACO, RC, and POOL questionnaires and then reported demographic information (gender and age). Data were excluded from the analysis if the participants failed to choose the correct answer of the “filter” items (e.g. “Please choose #1 on this question”). A total of 397 questionnaires were collected and 370 were valid (rejection rate = 6.80%).

Data analysis

SPSS and Amos 26.0 were used for data analysis. Pearson correlation analysis and structural equation model were conducted to test the hypotheses.

Results

Results of the correlation analysis

Pearson correlation was used to examine the correlations among the variables. Regarding the effects of demographic variables on academic dishonesty, age was positively correlated with academic dishonesty (r = 0.208, p < 0.01). As age increased, people were more likely to conduct various academic misconducts.

Regarding the effects of personality traits on academic dishonesty, as expected and in line with a prior study9, we found strong negative correlations between personality and academic dishonesty on all six dimensions. Specifically, academic dishonesty was negatively predicted by honesty-humility (r = − 0.362, p < 0.01), emotion stability (r = − 0.119, p < 0.05), agreeableness (r = − 0.246, p < 0.01), conscientiousness (t = − 0.231, p < 0.01), openness to experience (r = − 0.190, p < 0.01), and extraversion (r = − 0.185, p < 0.01).

Finally, regarding the effect of attitudes towards the rule on academic dishonesty, rule conditionality was positively correlated with academic dishonesty (r = 0.231, p < 0.01). It showed that academic misconduct was more acceptable as students scored higher on rule conditionality, consistent with the hypothesis. Contrary to the hypothesis, however, perceived obligation to obey the law/rule was not correlated with academic dishonesty (r = − 0.009, p = 0.864). In addition, POOL was also not associated with five of six personality dimensions nor rule conditionality (rHH = − 0.001, p = 0.984; rEM = 0.043, p = 0.413; rEX = 0.009, p = 0.861; rAG = 0.012, p = 0.816; rCO = 0.007, p = 0.897; rRC = − 0.016, p = 0.761) (see Table 1).

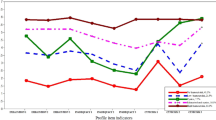

Results of the structural equation modeling

The structural equation models linking the demographic variables (age and gender), the personality variables (HEXACO), and the attitude variables (RC and POOL) were tested. The findings were presented in Fig. 1. The model was examined for the goodness of fit using indices including Chi-square, comparative fit index, and root mean square error of approximation. The results indicated an overall good model fix (χ2 = 180.714, χ2 /df = 2.82, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.922; RMSEA = 0.070)52.

In general, students’ tendency to engage in academic dishonesty was accounted for by the demographic variables, the personality variables, and the attitude variables. Specifically, consisting to the results of correlation analysis, age but not gender positively predicted academic dishonesty. The HEXACO model negatively predicted academic dishonesty, with five out of the six dimensions being significant except for the emotionality dimension. It indicated that people who scored higher on honesty-humility, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness to experience, and extraversion were less likely to engage in academic misconduct. In addition, rule conditionality positively predicted academic dishonesty, indicating that individuals who believed in the conditionality of rules were more likely to misbehave at school. These results partially aligned with the hypotheses.

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to explore the influence of individual factors (personality and people’s general attitudes toward the rules) on academic dishonesty. A survey among university students was conducted, and the results provided evidence that both personality traits and people’s rule orientation had significant effects on their various academic misconducts. The HEXACO model is a relatively recent personality model to expand and replace the Big Five personality model, and its cross-cultural applicability has been verified in many research settings41. The current study applied the HEXACO model in predicting academic dishonesty for the first time, and our findings justified its application.

Attitudes towards the rule are manifested in two aspects. Rule conditionality assessed whether individuals would violate relevant regulations and commit deviant behaviors under certain circumstances. Perception of the obligation to obey the law and rules (POOL) assessed individuals’ sense of duty to avoid behaviors that violate regulations, such as academic misconduct. Results of the current study demonstrated that rule conditionality positively predicted academic misconduct; that is, individuals who believed that rules are conditional and could be broken under certain conditions are more likely to engage in various academic transgressions. POOL, however, was not found to be related to academic dishonesty. Previous results showed that Chinese students scored lower on the POOL than American students53. POOL is likely an inadequate measure of Chinese students’ sense of obligation and duty to obey the laws and rules. Future research could use a different sample to test the predicting effect of POOL on academic dishonesty, and should also consider revising and refining the POOL measure for cultural research.

Regarding the predictive effect of demographic variables on academic misconduct, only age was found to have a significant positive correlation with academic misconduct. Gender had no effect which is consistent with the previous literature9,17.

Conclusion and implication for future research

The current study examined the HEXACO model and peoples’ attitudes toward the rule to better understand the academic misconduct behaviors among university students. Our findings have important implications for researchers and institutional educators. We demonstrated that in addition to the tractional big five personality factors, honesty-humility is a unique contributor to decreasing academic dishonesty. Recent studies have suggested focusing on integrity as the broadest defense against dishonesty in all spheres of academia54. Our research findings encourage university educators and institutional policymakers to pay much attention to this dispositional protector.

Our study also linked law-abiding attitudes with academic behaviors. Legal laws and academic rules share features in regulating people’s behaviors by imposing sanctions. They are quite different from social norms, which is a rather indirect way of behavior regulation. The current study confirmed that rule conditionality plays an important role in predicting academic misconduct of university students. Thus law-abiding education and behavior modification interventions might also be effective in preventing academic dishonesty.

Our results have contributed to the academic dishonesty field, but it is not free from limitations. First, it was a correlational study, meaning it is only possible to speak about relationships but not causal links. Experiments are necessary for future research. In addition, we did not control the participant’s prior academic performance. A previous study showed that students with lower than average performance tend to cheat55. Future research should control and study the links in a longitudinal data set. Finally, although the current research only focused on the impact of individual factors on academic misconduct, contextual factors could be considered using multi-level analysis.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the present study is a part of a bigger study that has not been completed yet, but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

McCabe, D. L. & Trevino, L. K. Individual and contextual influences on academic dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. Res. High. Educ. 38, 379–396 (1997).

Barrett, R. & Cox, A. L. ‘At least they’re learning something’: The hazy line between collaboration and collusion. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 30, 107–122 (2005).

Verhoef, A. H. & Coetser, Y. M. Academic integrity of university students during emergency. Transform. High. Educ. 6, a132 (2021).

Harding, T. S., Carpenter, D. D., Finelli, C. J. & Passow, H. J. Does academic dishonesty relate to unethical behavior in professional practice? An exploratory study. Sci. Eng. Ethics 10, 311–324 (2004).

Orosz, G. et al. Academic cheating and time perspective: Cheaters live in the present instead of the future. Learn. Individ. Differ. 52, 39–45 (2016).

Lawson, R. A. Is classroom cheating related to business students’ propensity to cheat in the “real world”?. J. Bus. Ethics 49, 189–199 (2004).

Nonis, S. & Swift, C. An examination of the relationship between academic dishonesty and workplace dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. J. Educ. Bus. 77, 69–77 (2001).

Brimble, M. & Stevenson-Clarke, P. Perceptions of the prevalence and seriousness of academic dishonesty in Australian universities. Aust. Educ. Res. 32, 19–44 (2005).

Lee, S. D., Kuncel, N. R. & Gau, J. Personality, attitude, and demographic correlates of academic dishonesty: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 146, 1042–1058 (2020).

McTernan, M., Love, P. & Rettinger, D. The influence of personality on the decision to cheat. Ethics Behav. 24, 53–72 (2014).

Williams, K. M., Nathanson, C. & Paulhus, D. L. Identifying and profiling scholastic cheaters: Their personality, cognitive ability, and motivation. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 16, 293–307 (2010).

Esteves, G. G. L., Oliveira, L. S., de Andrade, J. M. & Menezes, M. P. Dark triad predicts academic cheating. Personal. Individ. Differ. 171, 110513 (2020).

Stone, T. H., Jahwar, I. M. & Kisamore, J. L. Using the theory of planned behaviour and cheating justifications to predict academic misconduct. Career Dev. Int. 14, 221–241 (2009).

Curtis, G. J. et al. Self-control, injunctive norms, and descriptive norms predict engagement in plagiarism in a theory of planned behavior model. J. Acad. Ethics 16, 225–239 (2018).

Baumeister, R. F. & Tierney, J. Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength (Penguin, 2012).

Walton, C. L. T. An Investigation of Academic Dishonesty Among Undergraduates at Kansas State University (Kansas State University, 2010).

Roig, M. & Caso, M. Lying and cheating: Fraudulent excuse making, cheating, and plagiarism. J. Psychol. 139, 485–494 (2005).

Pavela, G. Judicial review of academic decision making after Horowitz. NOLPE School Law J. 8, 55–75 (1978).

McCabe, D. L. & Trevino, L. K. Academic dishonesty: Honor codes and other contextual influences. J. High. Educ. 64, 522–538 (1993).

Marques, T., Reis, N. & Gomes, J. A bibliometric study on academic dishonesty research. J. Acad. Ethics 17, 169–191 (2019).

Adesile, M. I. & Nordin, M. S. Predicting the underlying factors of academic dishonesty among undergraduates in public universities: A path analysis approach. J. Acad. Ethics 11, 103–120 (2013).

Ransome, J. & Newton, P. M. Are we educating educators about academic integrity? A study of UK higher education textbooks. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 126–137 (2018).

Krou, M. R., Fong, C. J. & Hoff, M. A. Achievement motivation and academic dishonesty: A meta-analytic investigation. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33, 427–458 (2021).

Jian, H., Li, G. & Wang, W. Perceptions, contexts, attitudes, and academic dishonesty in Chinese senior college students: A qualitative content-based analysis. Ethics Behav. 30, 543–555 (2020).

Lau, G. K. K., Yuen, A. H. K. & Park, J. Toward an analytical model of ethical decision making in plagiarism. Ethics Behav. 23, 360–377 (2013).

Kuntz, J. R. C. & Butler, C. Exploring individual and contextual antecedents of attitudes toward the acceptability of cheating and plagiarism. Ethics Behav. 24, 478–494 (2014).

Feather, N. T. Reactions to penalties for an offense in relation to authoritarianism, values, perceived responsibility, perceived seriousness, and deservingness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 71, 571–587 (1996).

Risser, S. & Eckert, K. Investigating the relationships between antisocial behaviors, psychopathic traits, and moral disengagement. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 45, 70–74 (2016).

Ampuni, S. et al. Academic dishonesty in Indonesian college students: An investigation from a moral psychology perspective. J. Acad. Ethics 18, 395–417 (2020).

King, C. G., Guyette, R. W. & Piotrowski, C. Online exams and cheating: An empirical analysis of business students’ views. J. Educ. Online 6, 11 (2009).

Peled, Y., Eshet, Y., Barczyk, C. & Grinautski, K. Predictors of Academic Dishonesty among undergraduate students in online and face-to-face courses. Comput. Educ. 131, 49–59 (2019).

Daty, T. K. Cheating From a Distance: An Examination of Academic Dishonesty Among University Students (University of New Haven, 2022).

Chiang, F. K., Zhu, D. & Yu, W. A systematic review of academic dishonesty in online learning environments. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 38, 907–928. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12656 (2022).

Steinberger, P., Eshet, Y. & Grinautsky, K. No anxious student is left behind: Statistics anxiety, personality traits, and academic dishonesty—lessons from COVID-19. Sustainability 13, 4762 (2021).

Eshet, Y., Steinberger, P. & Grinautsky, K. Relationship between statistics anxiety and academic dishonesty: A comparison between learning environments in social sciences. Sustainability 13, 1564 (2021).

Giluk, T. L. & Postlethwaite, B. E. Big Five personality and academic dishonesty: A meta-analytic review. Personal. Individ. Differ. 72, 59–67 (2014).

Graziano, W. G. & Eisenberg, N. Agreeableness: A dimension of personality. In Handbook of Personality Psychology (Academic Press, 1997)

Steel, P. The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychol. Bull. 133, 65–94 (2007).

Salgado, J. F. et al. Validity of the five-factor model and their facets: The impact of performance measure and facet residualization on the bandwidth-fidelity dilemma. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 24, 325–349 (2015).

Ashton, M. C. & Lee, K. Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 11, 150–166 (2007).

Zettler, I., Thielmann, I., Hilbig, B. E. & Moshagen, M. The nomological net of the HEXACO model of personality: A large-scale meta-analytic investigation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 15, 723–760 (2020).

Kleinlogel, E. P., Dietz, J. & Antonakis, J. Lucky, competent, or a just a cheat? Interactive effects of honesty-humility and moral cues on cheating behavior. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 44, 158–172 (2017).

Guo, Z., Li, W., Yang, Y. & Kou, Y. Honesty-Humility and unethical behavior in adolescents: The mediating role of moral disengagement and the moderating role of system justification. J. Adolesc. 90, 11–22 (2021).

Hilbig, B. E. & Zettler, I. When the cat’s away, some mice will play: A basic trait account of dishonest behavior. J. Res. Pers. 57, 72–88 (2015).

De Vries, R. E., Pathak, R. D., Van Gelder, J. L. & Singh, G. Explaining unethical business decisions: The role of personality, environment, and states. Personal. Individ. Differ. 117, 188–197 (2017).

Tyler, T. Procedural fairness and compliance with the law. Swiss J. Econ. Stat. 133, 219–240 (1997).

Tyler, T. Why People Obey the Law (Princeton University Press, 2006).

Van Rooij, B. et al. Compliance with COVID-19 mitigation measures in the United States. Amsterdam law school research paper 2020–21(2020).

Fine, A. et al. Rule orientation and behavior: Development and validation of a scale measuring individual acceptance of rule violation. Psychol. Public Policy Law 22, 314–329 (2016).

Adesile, M. I., Nordin, M. S., Kazmi, Y. & Hussien, S. Validating academic integrity survey (AIS): An application of exploratory and confirmatory factor analytic procedures. J. Acad. Ethics 14, 149–167 (2016).

Ashton, M. C. & Lee, K. The HEXACO-60: A short measure of the major dimensions of personality. J. Pers. Assess. 91, 340–345 (2009).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (The Guilford Press, 1998).

Van Rooij, B., Fine, A., Zhang, Y. & Wu, Y. Comparative compliance: Digital piracy, deterrence, social norms, and duty in China and the United States. Law Policy 39, 73–93 (2016).

Mahmud, S. & Ali, I. Evolution of research on honesty and dishonesty in academic work: A bibliometric analysis of two decades. Ethics Behav. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2021.2015598 (2021).

Whitley, B. E. Factors associated with cheating among college students: A review. Res. High. Educ. 39, 235–274 (1998).

Funding

Funding was provided by Jilin University Innovative Team of Philosophy and Social Sciences (Project entitled “Research on the Theories and Practices of Social Modernization”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.W. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared Table 1 and Figure 1. Y.Z. guided the revision of the manuscript. The authors share equal contributions to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Zhang, Y. The effects of personality traits and attitudes towards the rule on academic dishonesty among university students. Sci Rep 12, 14181 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18394-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18394-3

This article is cited by

-

A Richer Vocabulary of Chinese Personality Traits: Leveraging Word Embedding Technology for Mining Personality Descriptors

Journal of Psycholinguistic Research (2024)

-

HEXACO Personality Traits and Self-Control as Predictors of Counterproductive Academic Behavior

Journal of Academic Ethics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.