Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine cross-cultural differences, as operationalized by Schwartz's refined theory of basic values, in burnout levels among psychotherapists from 12 European countries during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. We focused on the multilevel approach to investigate if individual- and country-aggregated level values could explain differences in burnout intensity after controlling for sociodemographic, work-related characteristics and COVID-19-related distress among participants. 2915 psychotherapists from 12 countries (Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Great Britain, Serbia, Spain, Norway, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and Switzerland) participated in this study. The participants completed the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Service Survey, the revised version of the Portrait Values Questionnaire, and a survey questionnaire on sociodemographic, work-related factors and the COVID-19 related distress. In general, the lowest mean level of burnout was noted for Romania, whereas the highest mean burnout intensity was reported for Cyprus. Multilevel analysis revealed that burnout at the individual level was negatively related to self-transcendence and openness-to-change but positively related to self-enhancement and conservation values. However, no significant effects on any values were observed at the country level. Male sex, younger age, being single, and reporting higher COVID-19-related distress were significant burnout correlates. Burnout among psychotherapists may be a transcultural phenomenon, where individual differences among psychotherapists are likely to be more important than differences between the countries of their practice. This finding enriches the discussion on training in psychotherapy in an international context and draws attention to the neglected issue of mental health among psychotherapists in the context of their professional functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since Freud's1 early observation of the danger of analysis for the analyst, subsequent empirical studies have shown that psychotherapists may be vulnerable to burnout (see reviews and metanalyses2,3. Although this highly emotionally taxing helping profession should be a textbook example of a job with a high risk of burnout4,5,6,7, studies on burnout among psychotherapists are much less prevalent than those on burnout in other similar health professions such as physicians or nurses (see reviews and meta-analyses8,9,10,11,12). Thus, the issue of burnout in this occupation was and is still largely understudied in the fields of clinical psychology and psychotherapy, which are traditionally focused on the clients of psychotherapy rather than on psychotherapists13,14. However, several authors have observed that burned-out psychotherapists not only lose their ability to maintain their therapeutic relationship with clients and manage the whole therapeutic process15,16,17,18 but also experience a substantial decline in their well-being, accompanied by various somatic and psychological complaints19,20,21. Until now, the most commonly studied burnout risk factors among psychotherapists were either work-related (e.g., caseload and years of experience) or sociodemographic (sex and age)3. Much less attention was paid to the interpersonal and intrapersonal characteristics of therapists22. In addition, several studies found vast discrepancies in burnout prevalence among psychotherapists from various countries, ranging from 6%–54%3. To date, however, the cultural context has only been examined from the perspective of client outcomes, not how it potentially relates to a psychotherapist's functioning and well-being23. In our study, we followed the basic cultural values in the refined Schwartz value theory24,25 to assess burnout differences among psychotherapists from 12 European countries during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. To combine both individual and cultural perspectives, we employed the multilevel approach, which allowed us to evaluate burnout at different levels of this hierarchy simultaneously26,27. This approach may provide new insight into the fundamental question of whether burnout is a multidimensional phenomenon or unitary, single-factor syndrome consisting of interrelated symptoms27. In our study, we wanted to verify whether, among psychotherapists from these 12 countries, differences in professional burnout were associated with individual and country-aggregated Schwartz’s values, after controlling for sociodemographic and work-related characteristics as well as the COVID-19 distress.

According to Schwartz28, values are “desirable trans-situational goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in the life of a person or other social entity.” The recently refined theory of basic values24,25 highlights 19 basic values, which can be grouped into four higher-order values (self-transcendence, self-enhancement, openness to change, and conservation; see Measures section). These values were recognized in all major cultures29 and are associated distinctively with human attitudes, behaviors, and demographic variables. The main important assumption in this theory relates to a circular motivational continuum of values, which shows motivational conflict or compatibility across distinct values30,31. In other words, values can be compatible if decisions and behaviors that express the goals of one value also correspond to the goals of the other value. By contrast, values conflict if decisions or behaviors that express the goals of some values do so at the cost of other values. However, one of the still unresolved research questions is to what extent one may observe high within-country similarity and significant between-country variability in the culture as a shared meaning system32,33,34. This problem becomes even more interesting if there is a mismatch between individual values declared by a citizen of a particular country and a country-aggregated level of these values32. For example, Stephens et al.35 observed that a culturally mismatched environment can be associated with significant psychological distress, which can even impact the biological functioning of the person experiencing such mismatch. In the issue of psychotherapists, existing reviews and meta-analyses have revealed that the link between burnout and work-related factors may be modified by cultural differences, which shape not only the organizational characteristics of this profession but even the types of therapeutic relationships formed with clients2,3,9. Nevertheless, those cultural factors have never been explicitly measured in previous studies. Therefore our study is the first to apply a well-established theoretical model to interpersonal and cross-cultural comparisons of values and their potential impact on burnout among psychotherapists. Finally, we also took into account the most recent and thus, much understudied potential burnout risk factor among psychotherapists, which is the psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic36,37. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychotherapists were faced with many new challenges and obstacles regarding their therapeutic practice. Many psychotherapists either stopped working altogether or changed their practices in some form. One of the main challenges encompassed switching entirely or partly to providing psychotherapy in an online format. The above-mentioned factors were responsible for elevated levels of depression, anxiety and loneliness in this particular sample36. However, till now no studies have been conducted on how the COVID-19 pandemic could be related to burnout among psychotherapists employing cross-cultural comparisons.

Present Study

The main aim of this study was to examine the cross-cultural differences in burnout intensity among psychotherapists from 12 countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. We focused on the multilevel approach to investigate if individual- and country-aggregated level values, as operationalized by Schwartz's refined theory of basic values24,25, could explain differences in burnout after controlling for sociodemographic and work-related characteristics and COVID-19-related distress. We formulated the following hypotheses at the individual and country-aggregated levels to determine whether burnout in that specific occupation is more an individual syndrome or mostly shaped by the between-country differences in values declared by psychotherapists. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted on burnout in this group of participants using such a concrete model of culture and methodological design. Thus, our study is mainly explorative.

Hypothesis 1

Burnout among psychotherapists is significantly related to individual-level values (self-transcendence, self-enhancement, openness to change, and conservation) after controlling for sociodemographic and work-related characteristics and COVID-19-related distress.

Hypothesis 2

Burnout among psychotherapists is significantly related to country-aggregated values (self-transcendence, self-enhancement, openness to change, and conservation) after including all the variables from Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 3

Burnout among psychotherapists is related to cross-level interactions in a way that a higher level of burnout is associated with a higher mismatch between the values declared at the individual- and country-aggregated levels.

Methods

Participants

We conducted a cross-cultural survey using standardized questionnaires in online format (see below) via the specialized survey platform among psychotherapists from 12 European countries: Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Great Britain, Serbia, Spain, Norway, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and Switzerland. The data collection in all the countries was parallelly conducted between June 2020 and June 2021, during the second and third waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. The online set of the study questionnaires was sent in each country to the professional psychotherapeutic associations of various therapeutic modalities, which have distributed it among their members.

Finally, 2915 psychotherapists from the 12 countries representing various psychotherapeutic modalities participated in this study. The eligibility criteria encompassed certification (or being in the process of certification) in a particular psychotherapeutic modality and psychotherapeutic practice for at least 1 year. The participants completed the online versions of the questionnaires, which were preceded by detailed sociodemographic and work-related questions, including items on how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their practice and on potential psychological distress associated with the pandemic. In each country, participation was anonymous and voluntary, and the participants received no remuneration for participating in the survey. Informed consent was obtained from all participants of this study. The study protocol was accepted by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Psychology at the University of Warsaw in Poland. The sociodemographic and work-related variables and COVID-19-related distress among the psychotherapists from each country are presented in the Supplementary Tables. Finally, it is important to underline that this manuscript contains unique data, which has not been published in any other journal.

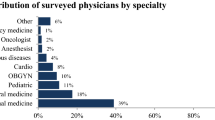

As can be seen in all the tables, age distributions were generally similar among all countries (M = 45.5 years, min. 21 years—max. 82 years). Regarding the participants' sexes, female psychotherapists were overrepresented (83%) in all of the countries. A significant number of participants were also in some form of stable relationships (75%). In terms of education, most participants held psychology degrees. However, Finnish and Swedish participants were almost evenly divided between having a psychology degree or a different degree such as social work, counseling, or nursing. In all 12 countries, most psychotherapists worked with adult clients. Nonetheless, a significant number of Polish and Bulgarian psychotherapists also worked with children. Having a private workplace was almost universal for therapists in all countries. Most psychotherapists in all the countries had already undergone their own psychotherapy. Supervision was provided once a month to the participants in most of the countries. However, Austrian psychotherapists used supervision quarterly, and most Spanish therapists did not use it at all. The results regarding therapeutic modalities varied across countries. Cognitive-behavioral therapy seemed to be the more common therapeutic approach in Cyprus, Spain, Poland, and Romania. Next, psychodynamic therapy was the dominant modality in Bulgaria, Norway, and Sweden. Austria and Switzerland seemed to favor Gestalt therapy. Finally, integrative psychotherapy was the most common approach in the United Kingdom. On average, psychotherapists in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Poland, Romania, and Serbia had between 6 and 11 years of experience in the profession. On the other hand, psychotherapists who were working in Austria, Spain, Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom had between 12 and 18 years of experience. In eight of the included countries (Austria, Cyprus, Finland, Spain, Norway, Romania, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom), most psychotherapists reported having a psychology certification (80% or more). The numbers appeared lower in Bulgaria, Poland, Serbia, and Sweden, with only approximately 35–65% of psychotherapists obtaining a certificate. Psychotherapists worked anywhere between a couple of hours a week and more than 20 h a week. More specifically, the average weekly workload in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Romania, and Serbia was between 1 and 10 h. In Sweden and the United Kingdom, the average was between 10 and 20 h a week. Psychotherapists who worked for more than 20 h a week were from Finland, Norway, and Poland. Austrian, Spanish, and Swiss psychotherapists were evenly divided between the last two workload categories. Finally, a general trend in working partially online during the COVID-19 pandemic was observed, with this being the case for psychotherapists in 11 countries (Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Spain, Norway, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Switzerland, and Sweden). At the time of data collection, UK therapists were still mostly providing their services online only.

Measures

To assess burnout, we used the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Service Survey (MBI-HS)6. All 12 language adaptations of the MBI-HS were bought from Mind Garden, the official distributor of the MBI-HS. The MBI-HS consists of 22 items and evaluates burnout and its three components: (1) Emotional Exhaustion (EE), nine items; (2) Personal Accomplishment (PA), eight items; and (3) Depersonalization (DP), five items. For each item, the respondent indicated the frequency of symptoms on a Likert-type scale from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). ). All the summed responses form an overall index, higher values of which indicate higher burnout. We decided to use the MBI-HS in our study for two reasons: First, it is the most popular and widely used burnout inventory focused especially on helping professions, which was the case in our research7,38. Second, the MBI-HS is the only tool available for the assessment of burnout with a wide spectrum of different language adaptations; as such, it is valuable in cross-cultural studies38.

To measure cultural values, the participants completed a revised version of the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ-R) developed by Schwartz et al.24. The PVQ-R consists of 57 short, sex-matched, verbal portraits of different people, each depicting a goal that is important to some person. For each portrait, respondents highlight how similar the person is to themselves on a 6-point Likert-type scale defined as follows: 1—not like me at all, 2—not like me, 3—a little like me, 4—moderately like me, 5—like me, and 6—very much like me. The participants' values are inferred from the values of the other people they described as similar to themselves. For example, a respondent who underlines that a person described as "Enjoying life's pleasures is important to her" is similar to herself, and probably attributes importance to hedonistic values. The PVQ-R assesses 19 values that can be combined into higher-order values, which was the case in our study: self-transcendence (universalism-nature, universalism-concern, universalism-tolerance, benevolence-care, and benevolence-dependability), self-enhancement (achievement, power dominance, and power resources), openness to change (self-direction thought, self-direction action, stimulation, and hedonism), conservation (security-personal, security-societal, tradition, conformity-rules, and conformity-interpersonal). All the language versions of the PVQ-R were provided by the author of this tool, S. Schwartz.

COVID-19 related distress was assessed via short, but reliable operationalization of this variable based on some other studies published at the time, when we started our research39,40. Namely, we asked participants on a Likert 1–5 point scale how stressful they found the situation in their role as psychotherapists caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The answers varied between 1 (“not at all)” to 5 (“very much”). We also examined the issue of changes in psychotherapy settings (i.e. online setting) imposed by the pandemic situation.

Data analysis

The data obtained had a two-level structure with persons (2915 units) nested within countries (12 units); thus, a cross-sectional multilevel model was adopted41. The explained variable was the burnout level among the psychotherapists, which was operationalized as the global burnout indicator. The explaining variables at Level 1 were the four higher-order values assessed by each person (see Measures section), centered on their means (centering on the group mean). The Level 2 variables were aggregates of the individual person's scores on four higher-order values to form a country mean of each value, which was then centered on the mean for all countries at a given value (see, centering on the grand mean). The maximum likelihood (ML) estimation method was used. For random effects (the random intercept model), the covariance structure of the variance components (VC) was assumed.

Unconditional (i.e., intercept only) modeling was the first step of the analysis. It was also used to obtain the interclass correlation coefficient (ICC)42, which informs about the proportion of variance in the burnout level explained by a grouping variable, that is, a country in which a participant is a psychotherapist. ICC values as low as 0.01 were treated as non-trivial43. Next, sociodemographic and work-related characteristics and COVID-19-related distress were added to the model. Continuous variables were centered on the group mean (e.g., age, work experience, and pandemic-related stress), whereas categorical variables were transformed into two dummy-coded categories (sex: female = 0, male = 1; relationship status: single = 0, in a stable relationship = 1; weekly workload: 0 = less than 20 h, 1 = 20 h and more; supervision: 0 = quarterly or less, 1 = once a month or more). In subsequent steps, only the variables found to be significantly related to the explained variable were taken into account44. In the third step, the Level 1 personal values were added, followed by the introduction of the Level 2 aggregates of these values for each country in the fourth step. Finally, the cross-level interactions of all values were tested45,46. For significant cross-level interactions, simple slopes, regions of significance, and confidence bands were established using the computational tools developed by Preacher et al.47. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 2748. Only the final hypothesis-testing models are presented in the article.

For model comparison, deviance statistics, based on χ2 distribution with the degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the number of parameters estimated in nested models, and the Akaike Information Criterion were used41.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics on burnout levels and the four higher-order values for each national sample of therapists.

Figure 1 illustrates the mean burnout levels at the country level. The lowest mean was noted for Romania, whereas the highest mean was reported for Cyprus. However, the ICC equals 0.09; thus, only 9% of the variance of burnout level in the study sample of psychotherapists was related to the country level.

Hypothesis testing

The results of the hypothesis testing are presented in Table 2.

For Hypothesis 1, the test revealed that the psychotherapist-reported self-transcendence and openness-to-change values that were higher than the typical values for a national sample were related to the lower overall burnout levels of the psychotherapists. On the other hand, the higher-than-typical self-enhancement and conservation values were related to higher overall burnout levels. Moreover, we observed significant associations of burnout with some of the sociodemographic and work-related characteristics as well as COVID-19-related distress. The burnout correlates were male sex, being single, younger age, and reporting more intense pandemic-related stress than typical for the national sample.

For Hypothesis 2, after controlling for all the variables mentioned in Hypothesis 1, the differences in values at the country-aggregated level were not significant for burnout.

Finally, with regard to Hypothesis 3, we observed significant cross-level interaction between openness-to-change values reported at individual- and aggregated country-level (B = − 3.81, SE = 1.92, t = 1.98, p < 0.05). The analysis of simple slopes is presented in Fig. 2. As can be observed, the openness-to-change values were more negatively related to burnout among psychotherapists in the countries with aggregated openness-to-change values higher than the cross-country average (Β = − 3.47, SE = 0.70, z = − 4.98, p < 0.001) in comparison to the countries for which these aggregated values were lower (Β = − 1.72, SE = 0.68, z = − 2.55, p < 0.05). Thus, the protective effect of being individually highly localized on openness-to-change values in the national sample was further amplified by originating from a country with aggregated openness-to-change values higher than the average for all 12 studied countries. Referring these results to the confidence bands of the aggregated values (− 61.83, − 0.29), inside which the simple slopes were equal to zero, we conclude that there was no relationship between personal openness-to-change values and burnout only for psychotherapists from Finland (Β = − 0.75, SE = 1.05, z = − 0.73, ns), which at the country level has the lowest openness to change among the studied countries. However, this result should be interpreted with caution as a model including interaction is not significantly better fitted to the data than a model including only main effects.

Discussion

The results of our study were in accordance with our hypotheses at the individual level rather than at the country-aggregated level of analysis. At the individual level, burnout was negatively related to the self-transcendence and openness-to-change values but positively related to the self-enhancement and conservation values. Although Schwartz's30 theory of basic human values has been used in hundreds of studies and various theoretical contexts24,25,49, it has not been applied to the issue of psychological disorders. Owing to the fact that this is the first study to link cross-cultural values to burnout syndrome among psychotherapists, this result is difficult to discuss other than exploratorily. Nevertheless, it is intriguing that motivational goals expressed in higher-order values of self-enhancement (e.g. power-dominance) and conservation (tradition, conformity-rules) were found to be burnout predictors, while motivational goals of self-transcendence (e.g. universalism-tolerance) and openness-to-change (e.g. self-direction thought) acted as buffers against burnout in this particular sample. Thus, our study may be an interesting adjunct to the literature on the psychological functioning of psychotherapists, including the neglected cross-cultural context2,3. As part of the psychotherapy training process, it is also important to consider this latter context.

However, the most intriguing finding was somehow a null result at the country-aggregated level. At this level, differences in values were irrelevant to the burnout levels of the participants. This was also confirmed by the comparisons of the effects at the individual and country levels. For example, we observed differences in burnout among the 12 countries, with the highest levels in Cyprus, Sweden, Norway, and the United Kingdom and the lowest levels in Romania, Serbia, and Finland. Nevertheless, these differences were explained almost entirely by interpersonal differences, as only 9% of the burnout variance was related to the country level. From a different perspective, burnout among psychotherapists tends to be a transcultural phenomenon rather than a country-specific problem. Although values do matter, their idiosyncratic aspect is more important for burnout than the collectivist aspect, i.e. shared by a group of representatives of this profession in a given country. This may be an important conclusion for reflection on the organizational structure and training in psychotherapy in Europe13,50.

The country-level aggregated values were found to be significant in the only observed cross-level interaction concerning openness to change. This supports the hypothesis on the role of fit between individual and collective values24,25. Namely, the protective effect of individual values was enhanced when being a psychotherapist in a country where other psychotherapists also declared high openness-to-change values. However, this result requires further research. Observing it only for this category of values may in fact be due to the specific circumstances of the study. The COVID-19 pandemic universally enforced adaptation to the "new normal". Burnout may therefore actually affect to a lesser extent those who consider openness to change as an important value in their lives since they have an intrinsic motivation for novelty and mastery, but this adaptation may also be facilitated or hindered by what happens in the social environment of such a person. The attitudes represented by one's occupational group, especially when the external demands include major changes in the conditions of work, are likely to become an influential reference point to modify an individual's appraisals and behaviors.

We found that higher burnout levels among psychotherapists were associated with sociodemographic data (younger age, being single, and male sex) and higher levels of COVID-19-related distress. Previous studies on burnout among psychotherapists have shown that younger psychotherapists are at greater risk of burnout than older psychotherapists and usually more experienced colleagues15,51,52,53. This finding is often explained by the fact that young psychotherapists may have high and unrealistic expectations about their roles in this occupation, and a subsequent reality crash may be a burnout catalyst52. Our study also showed that male psychotherapists can be at a higher risk of burnout than female psychotherapists, but the results reported in the literature on this topic are discrepant54,55. Our meta-analysis revealed that men and women may experience burnout in different ways; for example, women score higher on emotional exhaustion, whereas men score higher on depersonalization56. Consistent with our findings, the psychotherapy profession may also be associated with burnout among men due to sex-related differences in self-efficacy, which is usually higher among females in helping professions57. As expected, COVID-19-related distress was a significant burnout correlate in all the countries included in the study, which is consistent with the most recent research36,37. However, this subject is still understudied in general, particularly in this sample. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, psychotherapists were faced with many new challenges and obstacles regarding their practices, clients, and their well-being.

In a more general discussion, our findings contradict one of the main assumptions at the root of cross-cultural psychology, which is high within-country similarity and significant between-country variability in shared cultural meaning systems33,34,58. This notion suggests conducting cross-country comparisons by “unpacking” cultural differences within the studied psychological constructs and discussing them in light of a culture-comparative perspective33. Nevertheless, for at least two decades, attempts have been made to calculate the effect sizes of the aforementioned within-culture consensus and cross-cultural variability in several theoretical constructs59,60. Fisher and Schwartz32 examined values in 67 countries and observed negligible variances in value ratings that may be associated with country differences. Specifically, they found that the cross-country differences and within-country consensus in values were very low in all examined countries. Thus, we can infer that this is not because values are part of some shared meaning system defined as culture but because people, in general, differ in values regardless of where they come from. We obtained a similar pattern of results in this study. However, the aforementioned problem needs further examination, as we did not observe a consistent pattern of the effects of a mismatch between individual and country-aggregate values on burnout outcomes at the cross-level interactions (Fig. 2). The clinical context in cross-cultural psychology, that is, the role of values in psychological disorders, is, therefore, an important research gap to address in the future.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, including its large sample of psychotherapists from 12 different countries observed during the critical period of the COVID-19 pandemic and the use of a theoretical model for cross-cultural comparisons and a multilevel design, which make it a pioneer study in the relevant literature. However, several limitations should be mentioned. First, for organizational reasons, our samples of psychotherapists were heterogeneous concerning psychotherapeutic modalities and other work-related characteristics. In addition, they cannot be considered representative of the countries in which they were sampled. This represents a common shortcoming in the literature on the psychological functioning of this professional group3 but is hard to avoid, particularly in international comparisons and associated differences in regulations for this job between countries. Second, our research shares other common limitations in burnout studies among psychotherapists, including its cross-sectional design and precluding causal inferences2. The role of values in the prospective study design would be interesting to investigate to determine the stability of its effect at the individual and country levels. Two typical shortcomings must be borne in mind in cross-cultural research, namely the reference group effect61 and the response style effect62. The former deals with the problem of using a self-report measure to assess cross-cultural differences when participants compare themselves to familiar others (e.g., Poles compared themselves to other known Poles). The latter illustrates culture-related differences in response styles. These effects may also be the reason for the small effects of the country-aggregated level of analysis. However, another reason may be that there are not enough units of analysis at this level. A general rule of thumb is to have as many units at a higher level as possible63. In cross-cultural research, because of practical considerations, this rule is rarely fulfilled64. Finally, our study was not limited in terms of the number of countries, but also in terms of their location. The participants represented only European countries, which was due both to organizational issues, including the course of the pandemic, but also to the sharing of the basic foundations of psychotherapy as a profession. Future research should therefore focus on comparisons that cover a broader spectrum of countries.

Conclusions

In light of the recent inclusion of burnout in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases65, one should bear in mind that burnout is a global occupational phenomenon that can be observed in any profession10, including psychotherapists3. Our data suggest that burnout among psychotherapists may be, in some sense, a transcultural phenomenon, in which there is room for interplay between what is individual and what is shared with one's occupational group. However, the most important factors are the individual differences between psychotherapists, regardless of their cultures, at least across the studied European countries. Although this finding should be treated with caution because of the explorative characteristics and limitations of our study, it may be an enriching adjunct to the discussion on preventing psychotherapists’ burnout. Specifically, the results of our study call for the need to place more focus on psychotherapists’ personal values regarding their professional and private lives, especially during the psychotherapy training process. It has been found that these are crucial factors that promote the personal and professional quality of life in this profession66.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Freud, S. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (Macmillan, 1964).

Lee, M. K., Kim, E., Paik, I. S., Chung, J. & Lee, S. M. Relationship between environmental factors and burnout of psychotherapists: Meta-analytic approach. Couns. Psychother. Res. 20(1), 164–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12245 (2020).

Simionato, G. K. & Simpson, S. Personal risk factors associated with burnout among psychotherapists: A systematic review of the literature. J. Clin. Psychol. 74(9), 1431–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22615 (2018).

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F. & Schaufeli, W. B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499 (2001).

Maslach, C. Understanding burnout: Definitional issues in analyzing a complex phenomenon. In Job Stress and Burnout (ed. Paine, W. S.) 29–41 (SAGE, 1982).

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. & Leiter, M. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual (Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996).

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397–422. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Aronsson, G. et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4153-7 (2017).

Cieslak, R. et al. A meta-analysis of the relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress among workers with indirect exposure to trauma. Psychol. Serv. 11(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033798 (2014).

Guthier, C., Dormann, C. & Voelkle, M. C. Reciprocal effects between job stressors and burnout: A continuous time meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 146(12), 1146–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000304 (2020).

Koutsimani, P., Montgomery, A. & Georganta, K. The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 10, 284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284 (2019).

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P. & Maslach, C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev. Int. 14(3), 204–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430910966406 (2009).

Laverdière, O., Kealy, D., Ogrodniczuk, J. S. & Morin, A. J. S. Psychological health profiles of Canadian psychotherapists: A wake up call on psychotherapists’ mental health. Can. Psychol. 59(4), 315–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000159 (2018).

Laverdière, O., Ogrodniczuk, J. S. & Kealy, D. Clinicians’ empathy and professional quality of life. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 207(2), 49–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000927 (2019).

Ackerley, G. D., Burnell, J., Holder, D. C. & Kurdek, L. A. Burnout among licensed psychologists. Prof. Psychol. 19(6), 624–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.19.6.624 (1988).

Berjot, S., Altintas, E., Lesage, F.-X. & Grebot, E. The impact of work stressors on identity threats and perceived stress: An exploration of sources of difficulty at work among French psychologists. SAGE Open 3(3), 215824401350529. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013505292 (2013).

Farber, B. A. & Heifetz, L. J. The process and dimensions of burnout in psychotherapists. Prof. Psychol. 13(2), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.13.2.293 (1982).

Rupert, P. A. & Morgan, D. J. Work setting and burnout among professional psychologists. Prof. Psychol. 36(5), 544–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.5.544 (2005).

Raquepaw, J. M. & Miller, R. S. Psychotherapist burnout: A componential analysis. Prof. Psychol. 20(1), 32–6. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.20.1.32 (1989).

Rosenberg, T. & Pace, M. Burnout among mental health professionals: special considerations for the marriage and family therapist. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 32(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2006.tb01590.x (2006).

Rupert, P. A., Stevanovic, P. & Hunley, H. A. Work-family conflict and burnout among practicing psychologists. Prof. Psychol. 40(1), 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012538 (2009).

Rzeszutek, M. & Schier, K. Temperament traits, social support, and burnout symptoms in a sample of therapists. Psychotherapy 51(4), 574–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036020 (2014).

Lee, E., Greenblatt, A. & Hu, R. A knowledge synthesis of cross-cultural psychotherapy research: A critical review. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 52(6), 511–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220221211028911 (2021).

Schwartz, S. H. et al. Refining the theory of basic individual values. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 103(4), 663–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029393 (2012).

Schwartz, S. H. et al. Value tradeoffs propel and inhibit behavior: Validating the 19 refined values in four countries: Value tradeoffs and behavior. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 47(3), 241–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2228 (2017).

Bakker, A. B. & de Vries, J. D. Job Demands-Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress Coping 34(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695 (2021).

Gruszczynska, E., Basinska, B. A. & Schaufeli, W. B. Within- and between-person factor structure of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory: Analysis of a diary study using multilevel confirmatory factor analysis. PLoS ONE 16(5), e0251257. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251257 (2021).

Schwartz, S. H. Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values?. J. Soc. Issues 50(4), 19–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01196.x (1994).

Schwartz, S. H. et al. Extending the cross-cultural validity of the theory of basic human values with a different method of measurement. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 32(5), 519–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022101032005001 (2001).

Schwartz, S. H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 1–65 (Elsevier, 1992).

Schwartz, S. A Theory Of Cultural Value Orientations: Explication and applications. Comp Sociol. 5(2–3), 137–82. https://doi.org/10.1163/156913306778667357 (2006).

Fischer, R. & Schwartz, S. Whence differences in value priorities?: Individual, cultural, or artifactual sources. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 42(7), 1127–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110381429 (2011).

Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations (SAGE, 2001).

Leung, K. & van de Vijver, F. J. R. Strategies for strengthening causal inferences in cross cultural research: The consilience approach. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 8(2), 145–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595808091788 (2008).

Stephens, N., Townsend, S., Markus, H. & Phillips, L. A cultural mismatch: Independent cultural norms produce greater increases in cortisol and more negative emotions among first-generation college students. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48(6), 1389–1393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.07.008 (2012).

Brillon, P. et al. Psychological distress of mental health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison with the general population in high- and low-incidence regions. J. Clin. Psychol. 78, 602–621. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23238 (2021).

Summers, E. M. A., Morris, R. C., Bhutani, G. E., Rao, A. S. & Clarke, J. C. A survey of psychological practitioner workplace well-being. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 28(2), 438–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2509 (2021).

Leiter, M. P. & Maslach, C. Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burnout Res. 3(4), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2016.09.001 (2016).

Dragan, M., Grajewski, P. & Shevlin, M. Adjustment disorder, traumatic stress, depression and anxiety in Poland during an early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 12(1), 1860356. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1860356 (2021).

Gambin, M. et al. Generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms in various age groups during the COVID-19 lockdown in Poland. Specific predictors and differences in symptoms severity. Compr. Psychiatry. 105, 152222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152222 (2021).

Snijders, T. A. B. & Bosker, R. J. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling 2nd edn. (SAGE, 2012).

Kreft, I. & de Leeuw, J. Introducing Multilevel Modeling (SAGE Publications, Ltd, 1998).

Bliese, P. D. Group size, ICC values, and group-level correlations: A simulation. Organ. Res. Methods 1(4), 355–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819814001 (1998).

Becker, T. E. Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organ. Res. Methods 8(3), 274–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105278021 (2005).

Aguinis, H., Gottfredson, R. & Culpepper, S. Best-practice recommendations for estimating cross-level interaction effects using multilevel modeling. J. Manag. 39(6), 1490–1528. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313478188 (2013).

Hayes, A. A primer on multilevel modeling. Hum. Commun. Res. 32(4), 385–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2006.00281 (2006).

Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J. & Bauer, D. J. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 31(4), 437–48. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986031004437 (2006).

IBM. SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 270 2020 (IBM, 2020).

Cieciuch, J., Davidov, E., Vecchione, M. & Schwartz, S. H. A hierarchical structure of basic human values in a third-order confirmatory factor analysis. Swiss J. Psychol. 73(3), 177–82. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000134 (2014).

McCormack, H. M., MacIntyre, T. E., O’Shea, D., Herring, M. P. & Campbell, M. J. The prevalence and cause(s) of burnout among applied psychologists: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 9, 1897. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01897 (2018).

Berjot, S., Altintas, E., Grebot, E. & Lesage, F.-X. Burnout risk profiles among French psychologists. Burn. Res. 7, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2017.10.001 (2017).

Rupert, P. A. & Kent, J. S. Gender and work setting differences in career-sustaining behaviors and burnout among professional psychologists. Prof. Psychol. Res. P. 38(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.1.88 (2007).

van der Ploeg, H. M., van Leeuwen, J. J. & Kwee, M. G. Burnout among Dutch psychotherapists. Psychol. Rep. 67(1), 107–12. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1990.67.1.107 (1990).

Allwood, C. M., Geisler, M. & Buratti, S. The relationship between personality, work, and personal factors to burnout among clinical psychologists: Exploring gender differences in Sweden. Couns. Psychol. Q. 35, 324–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2020.1768050 (2020).

Emery, S., Wade, T. D. & McLean, S. Associations among therapist beliefs, personal resources and burnout in clinical psychologists. Behav. Change 26(2), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1375/bech.26.2.83 (2009).

Purvanova, R. K. & Muros, J. P. Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 77(2), 168–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.04.006 (2010).

Roohani, A. & Iravani, M. The relationship between burnout and self-efficacy among Iranian male and female EFL teachers. J. Lang. Educ. 6(1), 173–88. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2020.9793 (2020).

Poortinga, Y. H. & Van De Vijver, F. J. R. Explaining cross-cultural differences: Bias analysis and beyond. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 18(3), 259–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002187018003001 (1987).

Matsumoto, D., Grissom, R. J. & Dinnel, D. L. Do between-culture differences really mean that people are different?: A look at some measures of cultural effect size. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 32(4), 478–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022101032004007 (2001).

Schwartz, S. H. & Bardi, A. Value hierarchies across cultures: Taking a similarities perspective. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 32(3), 268–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022101032003002 (2001).

Heine, S. J., Lehman, D. R., Peng, K. & Greenholtz, J. What’s wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales?: The reference-group effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 82(6), 903–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.903 (2002).

van de Vijver, F. J. R. & Leung, K. Methods and data analysis of comparative research. In Handbook of Cross-cultural Psychology 2nd edn (eds Berry, J. W. et al.) 257–300 (Allyn & Bacon, 1997).

Snijders, T. Power and Sample Size in Multilevel Linear Models. Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118445112.stat06584 (2014).

Nezlek, J. B. Multilevel modeling and cross-cultural research. In Cross-Cultural Research Methods in Psychology (eds Matsumoto, D. & van de Vijver, F. J. R.) 299–345 (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

International Classification of Diseases (ICD). World Health Organization https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases. (Accessed: 6 Jan 2022)

Norcross, J. & VandenBos, G. Leaving it at the office: A Guide to Psychotherapist Self-care 2nd edn, 276 (The Guilford Press, 2018).

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the New Ideas of POB V project implemented within the scope of the "Excellence Initiative—Research University" Program, by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland (number PSP: 501-D125-20-5004310).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors took part in the data collection. A.V. and M.R. prepared the original version of the manuscript. A.V. and M.R., E.G. prepared results analysis. A.V. and M.R. prepared research plan. A.V., M.R., M.P., and E.G. prepared all visualisation of data and its interpretations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Hoy, A., Rzeszutek, M., Pięta, M. et al. Burnout among psychotherapists: a cross-cultural value survey among 12 European countries during the coronavirus disease pandemic. Sci Rep 12, 13527 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17669-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17669-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.