Abstract

The metabolic syndrome (MetS) has been well linked with coronary heart disease (CHD) in the general population, but studies have rarely explored their association among patients with stroke. We examine prevalence of MetS and its association with CHD in patients with first-ever ischemic stroke. This hospital-based study included 1851 patients with first-ever ischemic stroke (mean age 61.2 years, 36.5% women) who were hospitalized into two university hospitals in Shandong, China (January 2016–February 2017). Data were collected through interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory tests. MetS was defined following the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) criteria, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria, and the Chinese Diabetes Society (CDS) criteria. CHD was defined following clinical criteria. Data were analyzed using binary logistic regression models. The overall prevalence of MetS was 33.4% by NECP criteria, 47.2% by IDF criteria, and 32.5% by CDS criteria, with the prevalence being decreased with age and higher in women than in men (p < 0.05). High blood pressure, high triglycerides, and low HDL-C were significantly associated with CHD (multi-adjusted odds ratio [OR] range 1.27–1.38, p < 0.05). The multi-adjusted OR of CHD associated with MetS defined by the NECP criteria, IDF criteria, and CDS criteria (vs. no MetS) was 1.27 (95% confidence interval 1.03–1.57), 1.44 (1.18–1.76), and 1.27 (1.03–1.57), respectively. In addition, having 1–2 abnormal components (vs. none) of MetS was associated with CHD (multi-adjusted OR range 1.66–1.72, p < 0.05). MetS affects over one-third of patients with first-ever ischemic stroke. MetS is associated with an increased likelihood of CHD in stroke patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The metabolic syndrome (MetS), characterized by a constellation of multiple interrelated cardiometabolic risk factors, has become a major concern for public health1,2. Currently, several criteria are proposed to define MetS such as the US National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) criteria3, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria4, and the Chinese Diabetes Society (CDS) criteria5. Thus, the prevalence of MetS varies across studies, and even in the same population, depending on the defining criteria6.

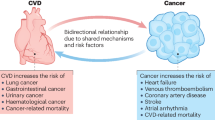

The associations between MetS and cardiovascular diseases have been well studied in the general population. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 87 population-based prospective studies showed that MetS was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, stroke) and cardiovascular mortality7. We previously reported that MetS was associated with coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, and cardiovascular multimorbidity among Chinese older adults living in a rural area6. So far, data are sparse with regard to the relationship between MetS and CHD among patients with ischemic stroke.

Ischemic stroke and CHD are common circulatory disorders among adults and share major common etiological factors (e.g., smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and high cholesterol) and pathophysiological mechanisms (e.g., atherosclerosis)8,9. However, evidence also suggests that the two entities show differences in risk factors, pathophysiologies, incidence, mortality, and prognosis in the general population10,11,12. As the worldwide leading causes of disability and death, CHD and ischemic stroke together have a great impact on public health13,14. A meta-analysis suggested that coronary stenosis was highly prevalent in patients with ischemic stroke and that CHD was the leading cause of death following the occurrence of acute ischemic stroke15. A large-scale register-based study in Sweden showed that ~ 50% of the men with both stroke and coronary disease died from coronary heart disease (e.g., myocardial infarction and sudden coronary death)10. Similarly, a recent large-scale retrospective cohort study also revealed the poor prognosis and an increased risk of cardiovascular complications following the onset of an ischemic stroke16. Thus, identifying risk factors for CHD among stroke patients is crucial to reduce the risk of coronary events and improve the prognosis.

In this hospital-based study of patients with first-ever acute ischemic stroke, we seek to describe the prevalence of MetS and CHD, and further to assess the association of MetS with CHD among the patients with ischemic stroke.

Methods

Study design and population

Data were obtained from the baseline survey of a hospital-based intervention study, the Multimodal Behavioral Intervention Study in Stroke, which is an ongoing randomized controlled multimodal intervention study in two hospitals, i.e., the Shandong Jining No. 1 People’s Hospital and the Jining Medical University Affiliated Hospital, Shandong, China17. The recruitment and baseline survey of participants was conducted from January 2016 to February 2017. In total, 2205 patients with first-ever acute ischemic stroke who were hospitalized into the above two hospitals were recruited based on the inclusion criteria similar to those specified in the China National Stroke Registry Protocol18: (a) first-ever ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA); (b) age ≥ 40 years; (c) patients, family or caregivers can provide consent; (d) others (e.g., direct admission based on physician evaluation or arrival through the emergency department, and confirmed by brain CT or MRI within 14 days after the onset of symptoms). Of the 2205 participants, we excluded 354 patients who had insufficient information to define MetS, leaving 1851 patients (83.9%) for the current analysis.

Data collection

Following the structured questionnaire, data were collected through interviews, clinical and neurological examinations, and laboratory tests by trained nurses, physicians, and technicians from the two hospitals, as previously reported19. Epidemiological data were collected via a questionnaire that was developed from the WHO STEPwise approach to Surveillance (STEPS) and the Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE)20,21.

MetS and its components

Waist circumference was measured at a point midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest in a horizontal plane using nonelastic tape. After at least a 5-min rest, arterial blood pressure was measured in the sitting position on the right arm using an electronic sphygmomanometer (HEM-7127J, Omron Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) with the cuff maintained at the heart level. Blood pressure was measured three times on one occasion, and the mean of the three readings was used in the analysis. After an overnight fast, peripheral blood samples were taken at the hospital. Fasting blood glucose, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were measured using an automatic Biochemical Analyser (Olympus AU-400, Olympus Optical Company, Tokyo, Japan) at the laboratory of the hospitals that is licensed by the local authority.

MetS were defined according to three sets of criteria: the NCEP criteria3, the IDF criteria4, and the CDS criteria5 (Table 1).

Definition of CHD

CHD was defined as coronary artery stenosis or occlusion caused by atherosclerosis in patients with a clear history of acute coronary syndrome or confirmed by coronary CT angiography or coronary angiography. The discharge diagnosis of CHD was made by senior cardiologists and neurologists via reviewing all medical records from comprehensive assessments during the hospitalization, which was based on medical history of CHD, clinical examinations, and instrumental assessments (e.g., coronary CT angiography or coronary angiography) following the current clinical guidelines22.

Covariates

The covariates included age, sex, education, and lifestyles (e.g., smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, and dietary). Education was categorized into 4 groups: illiteracy (no formal schooling education), primary school (1–6 years of education), middle school (7–9 years of education), and high school and above (≥ 10 years of education). Smoking status was categorized as no smoking and ever smoking. Alcohol consumption was defined as drinking alcohol more than once per month during the past year. Physical inactivity was defined as having not participated in any physical activity during leisure time. Information on dietary habits was collected on the frequency of vegetables or fruits and categorized into daily versus less than daily consumption.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of study participants were compared between men and women with Student t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Due to the skewed distribution, triglycerides were logarithmized before the comparison between men and women. Because around 73.3% of the participants had missing values on waist circumference, a linear regression model (R2 = 17%, p < 0.001) was used to predict and impute the waist circumference based on body mass index and demographic data, as previously reported23. The age- and sex-specific prevalence was graphed for MetS and CHD. Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of CHD associated with MetS and its components while adjusting for age, sex, education, smoking, alcohol drinking, physical activity, and dietary habits.

The IBM SPSS Statistics 25 for Windows (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for all analyses.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee at Jining Medical University, Shandong, China (No. 2015B006). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, or in case of cognitively impaired persons, from informants, usually the next-of-kin (spouse or children). Research within this project had been conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

The mean age of the 1851 participants was 61.2 (SD 9.7) years and 36.5% were women. Compared with men, women were older, less educated, and less likely to smoke, drink alcohol, and had higher levels of waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, triglycerides, and HDL-C, had a lower level of diastolic blood pressure (all p < 0.01) (Table 2). There was no significant sex difference in the prevalence of physical inactivity and daily eating fruits and vegetables (p > 0.10).

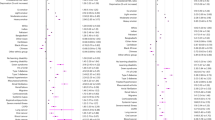

Figure 1 shows the age- and sex-specific prevalence of MetS defined by the three sets of criteria. The overall prevalence of MetS was 33.4% by NECP criteria, 47.2% by IDF criteria, and 32.5% by CDS criteria. For each criteria, women had a higher MetS prevalence than men across all age groups, and the sex difference disappeared after the age of 75 years. The prevalence of MetS decreased with age overall and for both men and women.

The overall prevalence of CHD among patients with ischemic stroke was 41.3% (48.1% in women; 37.4% in men, p < 0.05). The prevalence increased from 34.6% in those aged 40–54 years, 39.5% in those aged 55–64 years, 47.0% in those aged 65–74 years, to 51.8% in those aged ≥ 75 years, and the prevalence increased with age for both men and women (Fig. 2). The prevalence of CHD was higher in women than in men across all age groups.

In the total sample, high blood pressure, high serum triglycerides, and low HDL-C were significantly associated with CHD (OR ranged from 1.27 to 1.38), however, there was no significant association of abdominal obesity and high blood glucose with CHD (Table 3). The MetS defined by all three sets of criteria was associated with an increased likelihood of CHD, with the adjusted OR ranging from 1.27 to 1.44 (P < 0.05). When the analysis was stratified by sex, high blood pressure, high serum triglycerides, and MetS defined by IDF criteria was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of CHD in men, whereas among women, high serum triglycerides, low HDL-C, and MetS defined by all three sets of criteria were associated with CHD.

Furthermore, we categorized all participants into three groups according to the number of abnormal MetS components that were defined by each of the three MetS criteria, i.e., 0 (reference), 1–2, and ≥ 3 MetS components. In the total sample, compared to patients without abnormality in any of the five MetS components, having 1–2 and ≥ 3 abnormal MetS components was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of CHD (Table 4). There was no statistical interaction of MetS with sex on CHD. However, when the analysis was stratified by sex, the results showed that having 1–2 and ≥ 3 abnormal MetS components (vs. none) defined by all the three sets of criteria was significantly associated with an elevated likelihood of CHD in men, whereas in women only having ≥ 3 abnormal MetS components defined by the CDS criteria was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of CHD (Table 4).

Discussion

Summary of the main findings

MetS affects around one-third to nearly a half of patients with ischemic stroke, depending on the defining criteria for MetS, which ranged from 32.5% by CDS criteria and 33.4% by NECP criteria to 47.2% by IDF criteria. CHD was present in 41.3% of patients with ischemic stroke. The prevalence of both MetS and CHD was higher in women than in men, and the prevalence of CHD increased with age but the prevalence of MetS slightly decreased with age. In addition, MetS defined by all three sets of criteria was associated with an increased likelihood of CHD in patients with ischemic stroke. Notably, compared to patients without any of the five MetS components, having even 1–2 abnormal components was associated with a higher likelihood of CHD, especially in men.

Compared with other studies

In our study, the prevalence of MetS defined by IDF criteria was 47.2% among patients with ischemic stroke, which was in line with the report from another study of stroke patients in China (51.3%)24. However, our prevalence of MetS was lower than that in Polish stroke patients (61.2%) based on the same criteria25. The difference might be partly due to a higher proportion of women in the Polish study than ours (57.6% vs. 36.5%) because women are more likely to have MetS than men. Indeed, we found that women had a higher prevalence of MetS than men across all age groups, which is in line with the reports of previous studies2,25,26. The sex difference might be primarily attributable to the higher levels of MetS components (e.g., waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, blood glucose, and triglycerides) in women than in men.

In addition, we found that the prevalence of MetS slightly decreased with age in both men and women. This was different from the previous studies, which reported an increasing prevalence with age in young or middle-aged people27 but a relatively stable prevalence with age in older adults6,28. The decreasing prevalence of MetS with age may be explained by the age-related metabolic and pathophysiological changes, due to the fact that the levels of some MetS components, e.g., waist circumference, diastolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol, may not increase with age, especially in very old age29,30.

Coronary heart disease is highly prevalent in patients with ischemic stroke and the risk of long-term fatal CHD following the onset of clinical stroke or TIA is increased31. In addition, the follow-up study of patients with ischemic stroke showed that new-onset cardiovascular complications (e.g., acute coronary syndrome, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure) diagnosed following an ischemic stroke were very common and that the newly diagnosed cardiovascular complications in patients with ischemic stroke were associated with an increased risk of recurrent stroke16. We found that the overall prevalence of CHD was 41% in patients with ischemic stroke, which can be supported by the previous studies showing that coronary atherosclerosis is present in around 45% of stroke patients32,33.

The association between MetS and CHD

The meta-analysis revealed that MetS could double the risk of cardiovascular events in the general population7, but the risk of cardiovascular events associated with MetS in patients with stroke has not been well studied. Notably, whether the prognostic value of the MetS for cardiovascular events exceeds that of the sum of MetS individual components remains to be clarified34. This is releant because defining MetS as a binary entity (abnormalities in ≥ 3 vs. < 3 MetS components) might limit its power for predicting cardiovascular events35. Indeed, our study showed that having even 1–2 abnormal MetS components was associated with an increased likelihood of CHD. Thus, defining MetS as a binary entity could underestimate the association of clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors with risk of CHD. Our findings of the MetS-CHD associations among patients with ischemic stroke were consistent with those of our previous report from the general population of older adults living in the same area6. However, very few studies have investigated the association between MetS and risk of CHD in patients with clinical stroke, which limits the comparison of our results with the literature.

The underlying pathways linking MetS with CHD could be that MetS is associated with endothelial dysfunction and inflammation, which are key pathophysiologic features of atherosclerosis36. Atherosclerosis plays a key role in CHD through several critical processes in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (e.g., lipid accumulation, intimal thickening and fibrosis, vascular inflammation, remodeling, and plaque rupture or erosion)37. In addition, the ulceration of atherosclerotic plaques is very important in coronary occlusion38. Our analysis showed that having more components was linearly associated with an increased likelihood of CHD. This suggests that multiple individual MetS components may have an accumulative effect on the atherosclerotic process and increase the likelihood of CHD, which is in line with previous studies39.

Strengths and limitations

This hospital-based study includes a relatively large sample of patients with first-ever ischemic stroke who were mostly from the rural areas (26.7% illiteracy) of southwest Shandong province, a less developed region compared to the eastern coastal areas. In addition, trained staff and clinicians performed comprehensive assessments on a range of health-related factors and health conditions, which allowed us to define MetS with different criteria and to control for multiple potential confounders. However, this study also has limitations. First, because the study participants were recruited from local two university hospitals (tertiary hospitals), the patient sample might not be representative of the patient population. This should be kept in mind when generalizing our study findings. Second, a considerable proportion (73.3%) of participants had missing data on waist circumference, and an imputed waist circumference based on age, sex, and body mass index was used instead. However, this approach has previously been validated in terms of correct classification of abdominal obesity (88.4%) and cardiometablic risk (91.5% in men and 99.5% in women)23, thus, any bias from the missing waist circumference is likely to be minimal. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the study design does not allow us to determine the causal relationship between MetS and CHD, and the cross-sectional association might be subject to survival bias that usually leads to underestimation of the true associations.

Conclusions

Our hospital-based study of patients with first-ever acute ischemic stroke suggested that MetS affects around one-third to a half of stroke patients, depending on the criteria used for defining MetS, and that CHD was present in over 40% of the patients. Furthermore, MetS is associated with CHD in patients with ischemic stroke, and even having 1–2 abnormal components without meeting the criteria for MetS is associated with an increased likelihood of CHD. Our study also revealed sex differences in the prevalences of CHD and MetS as well as in the associations of MetS and its some components with CHD in patients with ischemic stroke. These results, if confirmed in follow-up studies, will add further evidence to the notion that proper management of MetS and individual components may benefit cardiovascular health in patients with stroke.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to current regulations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and approval from the data management committee.

Abbreviations

- MetS:

-

Metabolic syndrome

- NCEP:

-

National Cholesterol Education Program

- IDF:

-

International Diabetes Federation

- CDS:

-

Chinese Diabetes Society

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- TIA:

-

Transient ischemic attack

- STEPS:

-

WHO STEPwise approach to Surveillance

- SAGE:

-

Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Church, T. S. et al. Metabolic syndrome and diabetes, alone and in combination, as predictors of cardiovascular disease mortality among men. Diabetes Care 32, 1289–1294 (2009).

Gu, D. et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and overweight among adults in China. Lancet 365, 1398–1405 (2005).

Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 285, 2486–2497 (2001).

Alberti, K. G. et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 120, 1640–1645 (2009).

Chinese Diabetes Society. Chinese guideline for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (2017 edition). Chin. J. Diabetes Mellitus. 10, 4–67. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-5809.2018.01.003 (2018) (in Chinese).

Liang, Y. et al. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease in elderly people in rural China: A population-based study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 61, 1036–1038 (2013).

Mottillo, S. et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 56, 1113–1132 (2010).

Matsunaga, M. et al. Similarities and differences between coronary heart disease and stroke in the associations with cardiovascular risk factors: The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Atherosclerosis 261, 124–130 (2017).

Soler, E. P. & Ruiz, V. C. Epidemiology and risk factors of cerebral ischemia and ischemic heart diseases: Similarities and differences. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 6, 138–149 (2010).

Wilhelmsen, L. et al. Differences between coronary disease and stroke in incidence, case fatality, and risk factors, but few differences in risk factors for fatal and non-fatal events. Eur. Heart J. 26, 1916–1922 (2005).

Agmon, Y. et al. Relation of coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease with atherosclerosis of the thoracic aorta in the general population. Am. J. Cardiol. 89, 262–267 (2002).

Leening, M. J. G. et al. Comparison of cardiovascular risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke type in women. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e007514 (2018).

GBD Compare Data Visualization (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), University of Washington, 2016).

Ervasti, J. et al. Permanent work disability before and after ischaemic heart disease or stroke event: A nationwide population-based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ Open 7, e017910 (2017).

Gunnoo, T. et al. Quantifying the risk of heart disease following acute ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of over 50,000 participants. BMJ Open 6, e009535 (2016).

Buckley, B. J. R. et al. Stroke-heart syndrome: Incidence and clinical outcomes of cardiac complications following stroke. Stroke 53, 1759–1763 (2022).

Bai, B. et al. A randomised controlled multimodal intervention trial in patients with ischaemic stroke in Shandong, China: Design and rationale. Lancet 390, S13 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. The China National Stroke Registry for patients with acute cerebrovascular events: design, rationale, and baseline patient characteristics. Int. J. Stroke. 6, 355–361 (2011).

She, R. et al. Health-related quality of life after first-ever acute ischemic stroke: Associations with cardiovascular health metrics. Qual Life Res. 30, 2907–2917 (2021).

World Health Organization. The STEPS Instrument and Support Materials. https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/instrument/en/. Accessed 5 Dec 2020.

Kowal, P. et al. Data resource profile: the World Health Organization Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). Int. J. Epidemiol. 41, 1639–1649 (2012).

Levine, G. N. et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 68(10), 1082–1115 (2016).

Bozeman, S. R. et al. Predicting waist circumference from body mass index. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 12, 115 (2012).

Mi, D. et al. Investigators for the Survey on Abnormal Glucose Regulation in Patients with Acute Stroke Across China ACROSS-China. Metabolic syndrome and stroke recurrence in Chinese ischemic stroke patients—The ACROSS-China study. PLoS One. 7, e51406 (2012).

Brola, W. et al. Metabolic syndrome in polish ischemic stroke patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 24, 2167–2172 (2015).

Mabry, R. M. et al. Gender differences in prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: A systematic review. Diabet. Med. 27, 593–597 (2010).

Villegas, R. et al. Prevalence and determinants of metabolic syndrome according to three definitions in middle-aged Chinese men. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 7, 37–45 (2009).

He, Y. et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its relation to cardiovascular disease in an elderly Chinese population. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 1588–1594 (2006).

Qiu, C. Preventing Alzheimer’s disease by targeting vascular risk factors: Hope and gap. J. Alzheimers Dis. 32, 721–731 (2012).

Wang, R. et al. The age-related blood pressure trajectories from young-old adults to centenarians: A cohort study. Int. J. Cardiol. 296, 141–148 (2019).

Amarenco, P. & Steg, P. G. Stroke is a coronary heart disease risk equivalent: Implications for future clinical trials in secondary stroke prevention. Eur. Heart J. 29, 1605–1607 (2008).

Touboul, P. J. et al. Common carotid artery intima-media thickness and ischemic stroke: the GENIC case-control study. Circulation 102, 313–318 (2000).

Gongora-Rivera, F. et al. The prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with stroke. Stroke 38, 1203–1210 (2007).

Kahn, R. Metabolic syndrome—What is the clinical usefulness?. Lancet 371, 1892–1893 (2008).

Sone, H. et al. Is the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome useful for predicting cardiovascular disease in Asian diabetic patients? Analysis from the Japan Diabetes Complications Study. Diabetes Care 28, 1463–1471 (2005).

Kressel, G. et al. Systemic and vascular markers of inflammation in relation to metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in adults with elevated atherosclerosis risk. Atherosclerosis 202, 263–271 (2009).

Fairweather, D. Sex differences in inflammation during atherosclerosis. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 8(Suppl 3), 49–59 (2015).

Porambo, M. E. & DeMarco, J. K. MR imaging of vulnerable carotid plaque. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 10, 1019–1031 (2020).

Scuteri, A. et al. Metabolic syndrome amplifies the age-associated increases in vascular thickness and stiffness. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43, 1388–1395 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the study participants for their contribution to the multidomain behavioral interventions in ischemic stroke and all staff from the two participating hospitals for their collaboration in data collection and management.

Funding

Open access funding is provided by Karolinska Institutet. The multimodal behavioral intervention trial in patients with ischemic stroke was supported in part by Jining No. 1 People’s Hospital and the Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University, Jining, Shandong, China. Dr. Y Hao received a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Grant no. 81771360). Prof. B Bai received a grant from NSFC (Grant no. 81870948). Dr. Y Du received grants from the National Key R&D Program of the China Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant no. 2017YFC1310100) and NSFC (Grants no. 31711530157, 8171101298, and 8191101618). Dr. C Qiu received grants from the Swedish Research Council for Sino-Sweden Network on Aging Research and Sino-Sweden Joint Research Project (VR, Grants no. 2017-00740, 2017-05819, and 2020-01574), the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education (STINT, Grant no.: CH2019-8320), and Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. Dr. Y Liang received grants from the Swedish Research Council (VR, No. 2021-01107), and Karolinska Institutet, Sweden (No. 2018-01590). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design of the study: Y.L., Z.Y., Y.H., Z.Z., Y.D., J.D., B.B., and C.Q. Execution: Z.Y., Y.H., P.W., Z.Z., and B.B. Statistical analysis: Y.L. and Q.W.; Writing of the manuscript: Y.L. and C.Q. Critical revision of the manuscript and approval of the final versions for submission: all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, Y., Yan, Z., Hao, Y. et al. Metabolic syndrome in patients with first-ever ischemic stroke: prevalence and association with coronary heart disease. Sci Rep 12, 13042 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17369-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17369-8

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.