Abstract

This study aimed to compare compliance with 24-h movement guidelines across countries and examine the associations with markers of adiposity in adults from eight Latin American countries. The sample consisted of 2338 adults aged 18–65 years. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and sedentary behavior (SB) data were objectively measured using accelerometers. Sleep duration was self-reported using a daily log. Body mass index and waist circumference were assessed as markers of adiposity. Meeting the 24-h movement guidelines was defined as ≥ 150 min/week of MVPA; ≤ 8 h/day of SB; and between 7 and 9 h/day of sleep. The number of guidelines being met was 0.90 (95% CI 0.86, 0.93) with higher value in men than women. We found differences between countries. Meeting two and three movement guidelines was associated with overweight/obesity (OR: 0.75, 95% CI 0.58, 0.97 and OR: 0.69, 95% CI 0.51, 0.85, respectively) and high waist circumference (OR: 0.74, 95% CI 0.56, 0.97 and OR: 0.77, 95% CI 0.62, 0.96). Meeting MVPA and SB recommendations were related to reduced adiposity markers but only in men. Future research is needed to gain insights into the directionality of the associations between 24-h movement guidelines compliance and markers of adiposity but also the mechanisms underlying explaining differences between men and women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epidemiologic studies showed that sleep1, sedentary behavior2, and moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (MVPA)3 are associated with reduced morbidity and mortality in adults independent of age and sex. Given that a 24-h period consists of three types of movement behaviors (i.e., physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep)4, monitoring the levels and patterns of these behaviors is essential for health surveillance and for developing future preventative health strategies. Also, identifying those at risk due to unhealthy movement behavior patterns give a valuable information to tail future interventions as well as to permit an equitable allocation and provision of economic resources5.

Growing evidence shows that high MVPA, low sedentary behavior, and adequate sleep duration are collectively associated with a range of health benefits, such as lower body mass index and low waist circumference6,7. Based on the emerging evidence and a better understanding of the importance of considering these behaviors holistically, new public health guidelines that combine recommendations for physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep have been issued in many countries7,8,9,10,11,12. In addition, the World Health Organization has recently shown similar guidelines, but without a sleep recommendation for adults13,14. Determining individuals meeting these new public health guidelines is necessary to notify future health promotion and illness prevention policies and interventions. However, most previous studies have been conducted in the middle- and high-income countries15,16,17.

In the last two decades, Latin America has undergone important health and epidemiological transitions experiencing fast socioeconomic growth and lifestyle transformation18. This situation has been associated with an increase in diverse health risk factors but mainly overweight and obesity19. Alarming rates of overweight (32.0%) and obesity (19.6%) have been described in the Latin American countries, and these rates are projected to increase to 38.1 and 43.6%, respectively, by 203020. Furthermore, physical inactivity prevalence in Latin America is the highest reported worldwide21 and average sedentary behavior exceeds nine hours per day22.

A recent systematic review on 24-h movement guideline adherence and the relationship with markers of adiposity found five studies with adults from high-income countries (i.e., United States, Canada, Australia, Denmark, and Ireland)6. The authors showed that adults meeting all three guidelines (i.e., physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleep) had lower body mass index and waist circumference compared with those meeting none of the guidelines6. However, additional research is warranted to expand the knowledge on the associations of compliance with 24-h movement guidelines and body weight in adults from Latin America.

Multi-country data on compliance with 24-h movement behaviors is nonexistent in Latin America due mainly to the wide variety of sampling strategy used. Besides, the lack of standardized and validated measurements further makes it difficult to evaluate inter-country differences in compliance with 24-h movement behaviors in adults across Latin American countries. Thus, data collected in a single country or subnational region may show limited variance and results23,24,25. Examining data in different cultural and economic contexts can improve the understanding of the generalizability of the results. Therefore, the purposes of this study were (a) to compare compliance with 24-h movement guidelines across eight Latin American countries and (b) examine the associations between compliance with 24-h movement guidelines and markers of adiposity in adults. We hypothesized that (a) the number of guidelines being met and combinations of them would differ in Latin American adults across countries and (b) the number of guidelines being met and combinations of them would be inversely associated with markers of adiposity in adults from Latin America.

Methods

Study design and participants

The Latin American Study of Nutrition and Health (Estudio Latinoamericano de Nutrición y Salud; ELANS) was an observational, epidemiological, cross-sectional study conducted in eight Latin American countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela that focused only on urban areas. The data used in the present study were derived from the 2014–2015 cycle of the ELANS (https://es.elansstudy.com/) international database. A detailed description of the study design and sampling methodology can be found elsewhere26,27. The overarching ELANS protocol was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (#20140605) and is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (#NCT02226627). The ethical committee from each local institutional review board approved the ELANS study. The participants provided written informed consent/assent before data collection. All aspects of the study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The study was conducted using a complex and multistage cluster-stratified sampling design, representing all regions for each country and randomly selecting the main cities according to probability proportional to size method26,27. The sampling size required for essential accuracy was considered with a 95% confidence level, a maximum error of 3.5%, and a survey design effect of 1.75. Socioeconomic status was balanced based on national indices used in each country. Households were selected through systematic randomization. Selection of the respondent within a household was established using 50% of the sample next birthday, 50% last birthday, controlling quotas for sex, age, and socioeconomic level. Details have been previously published27,28.

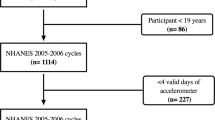

A total of 10,134 individuals (15.0–65.0 years) were invited to participate in the ELANS study; however, 9218 (47.8% men) agreed to participate. A subsample of 2737 participants aged 15–65 years used accelerometers, representing 29.6% of the ELANS population29,30. Due to logistical and financial reasons, efforts were made to confirm that 30% of the sample was assessed using accelerometers30,31,32.

We excluded adolescents aged 15–17 years from the manuscript because this study focused on the adult population. In addition, the 24-h movement guideline recommendations are different for adolescents and adults7,14. Furthermore, we also excluded participants aged 65 years based on the age range (i.e., 18–64 years) according to the Canadian guidelines to distinguish adults from older adults7. Therefore, the sample in the present manuscript consists of 2338 participants (53.4% women) aged 18–64 years with valid accelerometer data representing 23.6% of the total ELANS sample.

The protocol used in this manuscript included data collected during two home visits. The first visit included an assessment of markers of adiposity. Additionally, a subsample of the designated respondents received instructions regarding using accelerometers to measure MVPA and sedentary behavior; they were also provided with diaries (to complete for seven consecutive days). The second visit, which included administering the questionnaire and retrieving the accelerometers, and diaries, occurred eight days after the first visit for participants who were provided with the accelerometers.

Measures

Average time spent sedentary and in MVPA (min/day) was assessed using the GT3X + Actigraph (Fort Walton Beach, FL, United States). Prior studies have shown the GT3X + Actigraph to have acceptable technical reliability for sedentary behavior and MVPA33,34.

Participants were instructed to wear the accelerometer using an elasticized belt at the right hip (mid-axillary) during waking hours for seven consecutive days and to remove the device only when sleeping or for water activities (e.g., showering). The minimum wear time considered acceptable to be included in the study was five valid days, including least one weekend day, with at least 10 h of data following the removal for sleep time35. After excluding the nocturnal sleep period time, periods with at least 60 min of consecutive zero accelerometer counts were classified as non-wear time36.

Data were collected at a sampling frequency of 30 Hz, and subsequently downloaded using ActiLife Software (V6.0; ActiGraph, Pensacola, FL) in epochs of 60 s37. Sedentary behavior was defined as all activity below 100 counts per minute not including the sleep period and non-wear time. MVPA was defined as all behaviors greater or equal to 1952 counts per minute38,39. Sedentary behavior and MVPA were calculated and reported as minutes per day in the present analyses. Participants were instructed to complete a daily log, and to report the time they put the accelerometer belt on and the time when it was removed. Sleep duration was calculated by identifying non-wear time during valid accelerometer days, identifying the time between going to bed (removing the device) and waking up (wearing the device)40. Total sleep duration was presented as hours per night for analysis. Details on accelerometer data have been published elsewhere29,30.

In each country, the markers of adiposity (body weight, height, and waist circumferences) were measured while the participant wore light clothing and without shoes using standard procedures and equipment. Height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm with the participant’s head in the Frankfort Plane. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg after all outer clothing, heavy pocket items, shoes, and socks were removed with a calibrated electronic scale (Seca 213®, Seca Corporation Hamburg, Germany) using standard procedures41. Body mass index was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2) and was categorized as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) and obesity (≥ 30.0 kg/m2)42.

Waist circumference was measured with an inelastic tape to the nearest 0.1 cm. Measurements were taken midway between the lowest rib and the iliac crest on the horizontal plane, with the subject standing. We used the “substantially increased risk of metabolic complications (central obesity)” cutoff defined by World Health Organization, > 102 cm for men and > 88 cm for women42 in order to determine high waist circumference. These measurements of the markers of adiposity were completed in duplicate and the mean was considered for the analysis. Details on markers of adiposity have been published elsewhere31,32.

Sociodemographic variables were assessed using standard questionnaires during face-to-face interviews. Participants self-reported their age and were categorized into three age groups (18–34, 35–49, and 50–64 years) to obtain appropriate sample sizes. In addition, participants reported, sex (women, men), and marital status (single [not married, widowed, and divorced] and married). Further, education level data was divided into three strata: low (basic or lower), middle (elementary), and high (university degree) for all countries. Details on sociodemographic variables have been published previously26,29.

Data analysis

Weighting was done according to sociodemographic characteristics, sex, socioeconomic level, and country22,27. Mean, 95% confidence interval (95% CI), and percentages were computed, as appropriate, to describe the variables by sociodemographic variables.

Each participant was categorized as either “meeting” or “not meeting” the time-specific recommendations outlined within the Canadian 24-h Movement Guidelines for adults aged 18–64 years. The recommendations were as follows: (1) engage in at least 150 min/week of MVPA; (2) spend ≤ 8 h/day in sedentary behavior; and (3) obtain between 7 and 9 h/day of sleep. The participants who met all three recommendations for MVPA, sedentary behavior, and sleep duration were categorized as meeting the integrated Canadian 24-h movement guidelines. The proportion of participants meeting the physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep duration recommendations by sex and by country were also calculated.

To obtain a complete profile of the 24-h compliance with movement guidelines, two variables were used in this study: (a) the a number of the guidelines being met (from 0 = “no guideline met” to 3 = “all three guidelines met”), and (b) combinations of the guidelines being met as a category variable (“none”, “MVPA guideline met”, “only sedentary behavior guideline met”, “only sleep guideline met”, “both the MVPA and sedentary behavior guidelines met”, “both the MVPA and sleep guidelines met”, “both the sedentary behavior and sleep guidelines met”, and “all three guidelines met”). Country differences in compliance with 24-h movement guidelines were tested using one-way ANOVA (dependent variable was the number of the guidelines being met) and Chi-square test (dependent variable was combinations of the guidelines being met).

The adjusted odds ratio (OR) and respective 95% CI were obtained from multivariable logistic regression models investigating the odds of two different outcomes: (a) overweight/obesity classification based on body mass index and (b) as above thresholds based on waist circumference42. The models are presented by sex adjusted for age, education level, marital status, and country. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used to interpret inferential analyses. All analyses were performed using SPSS V22 software (SPSS Inc., IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, NY, USA).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was provided by the Western Institutional Review Board (#20140605), and by the ethical review boards of the participating institutions. ELANS is registered at Clinical Trials #NCT02226627. Written informed consent/assent was obtained from all individuals, before commencement of the study.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive characteristics. The sample consisted of 2338 participants (Mean: 38.2, 95% CI 37.7, 38.7) with 53.4% women (95% CI 51.4, 55.4); 44.7% (95% CI 42.7, 46.7) of participants were aged < 35 years; over half (56.8%, 95% CI 54.7, 58.8) were classified as having a low education level; 52.5% (95% CI 50.5, 54.5) were married. The country with the lowest proportion of participants was Ecuador (10.7%, 95% CI 9.4, 11.9), and the highest was Brazil (19.5%, 95% CI 17.9, 21.1).

The means (95% CI) of MVPA (min/day), sedentary behavior (min/day), and sleep duration (h/day) across the entire sample were 34.5 (95% CI 33.6, 35.5), 568.9 (95% CI 564.1, 573.3), and 9.6 (95% CI 9.4, 9.7), respectively. Mean weight and height was 72.6 kg (95% CI 72.0, 73.2), 162.8 cm (95% CI 162.1, 163.4), respectively. Mean adiposity markers were 27.3 kg/m2 (95% CI 26.7, 28.0), and 89.7 cm (95% CI 89.1, 90.3) for body mass index, and waist circumference (Table 2).

The number of participants meeting the 24-h movement guidelines was markedly higher in men than in women (1.02 [95% CI 0.98, 1.07] and 0.78 [95% CI 0.73, 0.82], p < 0.001). On average, the number of the guidelines being met in participants ranged from 0.74 (95% CI 0.65, 0.82, Venezuela) to 1.14 (95% CI 1.03, 1.24, Chile) with significant differences across countries (p < 0.001). Country differences (p < 0.001) were also found for the combinations of the guidelines being met. Specifically, around 0.3% of adults in Colombia met all three guidelines, while 4.6% of participants from Chile met all three guidelines. No sex differences were observed for compliance with all three movement guidelines (p = 0.126) (Table 3).

Compliance with two and three guidelines was negatively associated with overweight/obesity (OR: 0.75, 95% CI 0.58, 0.97 and OR: 0.69, 95% CI 0.51, 0.85) and having high waist circumference (OR: 0.74, 95% CI 0.56, 0.97 and OR: 0.77, 95% CI 0.62, 0.96) in adults after adjustment for age, education level, marital status, and country. These results, however, only remained in men. At the same time, there were no significant associations between meeting movement guidelines and adiposity measures in women. The associations were not significant between meeting sleep duration with markers of adiposity (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study examined compliance with 24-h movement guidelines and the associations between compliance with 24-h movement guidelines and markers of adiposity in adults from eight Latin American countries. Overall, the proportion of adults complying with all 24-h movement behavior guidelines was small (1.6%). Besides, we found significant differences in compliance with the 24-h movement guidelines among countries. Furthermore, the number of guidelines being met was negatively associated with measures of adiposity in men but not in women.

This study is the first to examine compliance with 24-h movement guidelines in adults from Latin American countries. Thus, contributing to the previous literature by examining how meeting 24-h movement guidelines is associated with markers of adiposity. Two recent systematic reviews with compositional data analysis studies described that the composition of movement behaviors across the 24-h day (including physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep) was associated with all-cause mortality, markers of adiposity (i.e., body mass index, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and body fat), cardiometabolic biomarkers, and mental health6,43.

A negative association between the number of the guidelines being met and markers of adiposity was detected in Latin American adults. Our findings corroborate previous studies from high-income countries (for instance, the United States, Canada, and Denmark), which showed an increased likelihood for obesity in participants not meeting any of the movement guidelines7,44,45. A recent systematic review7 indicates that only two international studies44,45 examined the relationship between 24-h movement guidelines and markers of adiposity in adults. Both of which found that the distribution of time spent in 24-h movement behaviors was significantly associated with body mass index and waist circumference. For instance, in one study45 the strongest favorable association was found for the proportion of time spent in MVPA whereas unfavorable associations were found for the proportion of time spent in light physical activity and sedentary behavior. Our findings suggest that men from Latin America meeting more movement guidelines of MVPA, sedentary behavior, and adequate sleep were more likely to have lower body mass index and waist circumference. A relevant finding is that Latin American adults meeting more guidelines had healthier lifestyles such as sufficient MVPA, reduced sedentary activities, and adequate sleep. These healthy lifestyle behaviors may reduce the risk of overweight and obesity in adults. It should be acknowledged that current evidence for the association between the number of 24-h movement guidelines and adiposity in adults is still understudied in Latin America. Therefore, future research is recommended, including longitudinal study designs, to examine the potential direction of the associations.

We found that adults meeting both the physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines were more likely to have lower odds ratios for body mass index and waist circumference than those meeting none. This finding suggests that a combination of sufficient MVPA and less sedentary behavior provides beneficial effects on maintaining healthy body weight in adults. Furthermore, this study did not detect a significant association between meeting MVPA plus sedentary behavior and sedentary behavior plus sleep with markers of adiposity, with the reference category of meeting none of the guideline in women. These findings are essential for understanding 24-h movement behaviors in Latin American adults and for establishing evidence-based intervention for preventing overweight and obesity.

The current findings suggest differences in the association between guideline adherence and body composition by sex. In international studies, low adherence to the MVPA and sleep duration recommendation has been previously described among women46,47. Particularly Latin American women seem to lag behind in MVPA compared with men in international research24,29,48. Increasing MVPA levels and sleep duration would be favorable for the population49,50 and would also increase the proportion of Latin American adults meeting the integrated 24-h movement recommendations. Intervention and public health promotion efforts to inspire MVPA and adequate sleep time, which enhance compliance with the 24-h movement guideline recommendations are essential in this group.

Several countries' development and release of evidence on 24-h movement guidelines7,8,9 characterize a new public health approach by providing specific recommendations for a healthy 24-h period, including time spent in physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep. The guidelines recognize that focusing on a single behavior has limitations and suggest that a combination of movement behaviors (physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep) matters for health and healthy development. Given that most Latin American adults do not met all movement guidelines, consideration should be given to presenting adequate behavior to multiple behavior change. Certainly, it has been theorized that a sequential rather than simultaneous approach to multiple movement behavior change may be more successful. Our findings illustrate important considerations that must be made about the content of Guidelines released in Latin America.

This study has several significant limitations and strengths. One limitation of the study is the cross-sectional design which cannot reveal the causality. Another potential limitation was that sleep duration was derived from the non-wear time of valid days. Sleep time was calculated using the device removal time during night time. This may overestimate sleep time, as participants may remove the device before effectively going to sleep and start wearing it sometime after waking up. However, to minimize this issue, participants were specifically instructed to only remove the device when going to sleep and wearing it immediately after waking up. Participants took notes in their daily logs, which were matched to identify potential problems. Wearing an accelerometer for too few hours per day can result in an underestimation of time spent in different physical activity intensity categories. Assessing physical activity for more hours per day can provide a more accurate picture of the true levels of physical activity and avoid misclassification bias51,52. Misclassification of physical activity can bias results of studies toward the null, alter the interpretations for dose–response relationships between physical activity and inactivity exposures and health outcomes, modify the proportion of adults meeting public health physical activity recommendations, and change the interpretations of intervention studies. Furthermore, the ELANS study did not assess recreational screen time as suggested in previous guidelines7. As there are no specific public health recommendations concerning 24-h Movement Guidelines for inhabitants from Latin America, the study also relied on the Canadian movement guidelines. On the other hand, there are several strengths of the present study. We used a large sample size from eight Latin American countries using a rigorous quality control program to ensure high quality data across all countries. Furthermore, we present objective measures to assess MVPA and sedentary behavior, which is rare in Latin America31,53.

Conclusion

We showed that less than 2% of adults met all three movement guidelines. Effective strategies are, therefore, needed to promote healthy lifestyles in Latin American adults. Particularly, engagement in more MVPA and less sedentary behavior along with adequate sleep should be encouraged in Latin American adults, mainly women from urban areas.

To improve empirical evidence for developing evidence-based 24-h movement guidelines for the Latin American adult population, future research is recommended that uses perspective and intervention designs to examine the associations between compliance with 24-h movement guidelines and relevant health outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the terms of consent/assent to which the participants agreed but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author to discuss availability of data and materials.

References

Wang, C. et al. Association of estimated sleep duration and naps with mortality and cardiovascular events: a study of 116 632 people from 21 countries. Eur. Heart J. 40, 1620–1629. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy695 (2019).

Rezende, L. F. M., Lee, D. H., Ferrari, G. & Giovannucci, E. Confounding due to pre-existing diseases in epidemiologic studies on sedentary behavior and all-cause mortality: a meta-epidemiologic study. Ann. Epidemiol. 52, 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.09.009 (2020).

Wang, Y., Nie, J., Ferrari, G., Rey-Lopez, J. P. & Rezende, L. F. M. Association of physical activity intensity with mortality: a national cohort study of 403681 US adults. JAMA Intern. Med. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6331 (2020).

Tremblay, M. S. et al. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN)-terminology consensus project process and outcome. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act 14, 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0525-8 (2017).

Bauman, A. E. et al. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not?. Lancet 380, 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1 (2012).

Rollo, S., Antsygina, O. & Tremblay, M. S. The whole day matters: Understanding 24-hour movement guideline adherence and relationships with health indicators across the lifespan. J. Sport Health Sci. 9, 493–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2020.07.004 (2020).

Ross, R. et al. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for adults aged 18–64 years and adults aged 65 years or older: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 45, S57–S102. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0467 (2020).

Okely, A. D. et al. A collaborative approach to adopting/adapting guidelines: the Australian 24-hour movement guidelines for the early years (birth to 5 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep. BMC Public Health 17, 869. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4867-6 (2017).

Reilly, J. J. et al. GRADE-ADOLOPMENT process to develop 24-hour movement behavior recommendations and physical activity guidelines for the under 5s in the United Kingdom, 2019. J. Phys. Act Health 17, 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2019-0139 (2020).

New Zealand Ministry of Health. Sit Less, Move More, Sleep Well: Physical Activity Guidelines for Children and Young People (Ministry of Health, 2017).

Tremblay, M. S. et al. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41, S311-327. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2016-0151 (2016).

Tremblay, M. S. et al. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for the early years (0–4 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. BMC Public Health 17, 874. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4859-6 (2017).

World Health Organization. Guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age. World Health Organization. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311664 (2019).

Bull, F. C. et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 54, 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955 (2020).

Weatherson, K. A. et al. Post-secondary students’ adherence to the Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for adults: results from the first deployment of the Canadian campus wellbeing survey (CCWS). Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 41, 173–181. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.41.6.01 (2021).

Khan, A., Lee, E. Y. & Tremblay, M. S. Meeting 24-h movement guidelines and associations with health related quality of life of Australian adolescents. J. Sci. Med. Sport 24, 468–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2020.10.017 (2021).

Zhu, X., Healy, S., Haegele, J. A. & Patterson, F. Twenty-four-hour movement guidelines and body weight in youth. J. Pediatr. 218, 204–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.11.031 (2020).

Greene, J. & Guanais, F. An examination of socioeconomic equity in health experiences in six Latin American and Caribbean countries. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 42, e127. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2018.127 (2018).

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 390, 2627–2642. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3 (2017).

Kelly, T., Yang, W., Chen, C. S., Reynolds, K. & He, J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 32, 1431–1437. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.102 (2008).

Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M. & Bull, F. C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 4, 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2 (2020).

Ferrari, G. L. M. et al. Socio-demographic patterning of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviours in eight Latin American countries: findings from the ELANS study. Eur. J. Sport Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2019.1678671 (2019).

Figueiredo, T. K. F. et al. Changes in total physical activity, leisure and commuting in the largest city in Latin America, 2003–2015. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 24, e210030. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-549720210030 (2021).

Werneck, A. O. et al. Macroeconomic, demographic and human developmental correlates of physical activity and sitting time among South American adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 17, 163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01068-6 (2020).

Troncoso, C. et al. Patterns of healthy lifestyle behaviours in older adults: findings from the Chilean National Health Survey 2009–2010. Exp. Gerontol. 113, 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2018.09.026 (2018).

Fisberg, M. et al. Latin American Study of Nutrition and Health (ELANS): rationale and study design. BMC Public Health 16, 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2765-y (2016).

Ferrari, G. et al. Is the perceived neighborhood built environment associated with domain-specific physical activity in Latin American adults? An eight-country observational study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act 17, 125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01030-6 (2020).

Ferrari, G. et al. Agreement between self-reported and device-based sedentary time among eight countries: findings from the ELANS. Prev. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01206-x (2021).

Ferrari, G. L. M. et al. Socio-demographic patterning of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviours in eight Latin American countries: findings from the ELANS study. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 20, 670–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2019.1678671 (2020).

Ferrari, G. L. M. et al. Methodological design for the assessment of physical activity and sedentary time in eight Latin American countries-the ELANS study. MethodsX https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2019.100788 (2020).

Ferrari, G. L. M. et al. Comparison of self-report versus accelerometer-measured physical activity and sedentary behaviors and their association with body composition in Latin American countries. PLoS ONE 15, e0232420. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232420 (2020).

Ferrari, G. et al. A comparison of associations between self-reported and device-based sedentary behavior and obesity markers in adults: a multi-national cross-sectional study. Assessment https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911211017637 (2021).

Sasaki, J. E., John, D. & Freedson, P. S. Validation and comparison of ActiGraph activity monitors. J. Sci. Med. Sport 14, 411–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2011.04.003 (2011).

Yano, S. et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior assessment: a laboratory-based evaluation of agreement between commonly used actigraph and omron accelerometers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173126 (2019).

Brond, J. C. & Arvidsson, D. Sampling frequency affects the processing of actigraph raw acceleration data to activity counts. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 120, 362–369. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00628.2015 (2016).

Troiano, R. P. et al. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 40, 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3 (2008).

Colley, R., Connor Gorber, S. & Tremblay, M. S. Quality control and data reduction procedures for accelerometry-derived measures of physical activity. Health Rep. 21, 63–69 (2010).

Matthews, C. E. et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003–2004. Am. J. Epidemiol. 167, 875–881. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm390 (2008).

Freedson, P. S., Melanson, E. & Sirard, J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 30, 777–781. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021 (1998).

Urbanek, J. K. et al. Epidemiology of objectively measured bedtime and chronotype in US adolescents and adults: NHANES 2003–2006. Chronobiol. Int. 35, 416–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2017.1411359 (2018).

Lohman, T. G., Roche, A. F. & Martorell, R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual Vol. 24 (Human Kinetics Press, 1988).

World Health Organisation (WHO). WHO | Waist Circumference and Waist–Hip Ratio. Report of a WHO Expert Consultation. Geneva, 8–11 (2008).

Janssen, I. et al. A systematic review of compositional data analysis studies examining associations between sleep, sedentary behaviour, and physical activity with health outcomes in adults. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 45, S248–S257. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2020-0160 (2020).

Gupta, N. et al. Movement behavior profiles and obesity: a latent profile analysis of 24-h time-use composition among Danish workers. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 44, 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-019-0419-8 (2020).

Chastin, S. F., Palarea-Albaladejo, J., Dontje, M. L. & Skelton, D. A. Combined effects of time spent in physical activity, sedentary behaviors and sleep on obesity and cardio-metabolic health markers: a novel compositional data analysis approach. PLoS ONE 10, e0139984. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139984 (2015).

Lee, E. Y., Carson, V., Jeon, J. Y., Spence, J. C. & Tremblay, M. S. Levels and correlates of 24-hour movement behaviors among South Koreans: Results from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2014 and 2015. J. Sport Health Sci. 8, 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2018.11.007 (2019).

Liangruenrom, N., Dumuid, D., Craike, M., Biddle, S. J. H. & Pedisic, Z. Trends and correlates of meeting 24-hour movement guidelines: a 15-year study among 167,577 Thai adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act 17, 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-01011-9 (2020).

Loyen, A. et al. Sedentary time and physical activity surveillance through accelerometer pooling in four European countries. Sports Med. 47, 1421–1435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0658-y (2017).

Wang, Y., Nie, J., Ferrari, G., Rey-Lopez, J. P. & Rezende, L. F. M. Association of physical activity intensity with mortality: a national cohort study of 403681 US adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 181, 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6331 (2021).

Wilunda, C. et al. Sleep duration and risk of cancer incidence and mortality: a pooled analysis of six population-based cohorts in Japan. Int. J. Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.34133 (2022).

Herrmann, S. D., Barreira, T. V., Kang, M. & Ainsworth, B. E. How many hours are enough? Accelerometer wear time may provide bias in daily activity estimates. J. Phys. Act Health 10, 742–749. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.10.5.742 (2013).

Herrmann, S. D., Barreira, T. V., Kang, M. & Ainsworth, B. E. Impact of accelerometer wear time on physical activity data: a NHANES semisimulation data approach. Br. J. Sports Med. 48, 278–282. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2012-091410 (2014).

Ferrari, G. et al. Accelerometer-measured daily step counts and adiposity indicators among Latin American adults: a multi-country study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094641 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff and participants from each of the participating sites who made substantial contributions to ELANS.

Funding

Fieldwork and data analysis compromised in ELANS protocol was supported by a scientific grant from the Coca Cola Company, and by grant and/ or support from Instituto Pensi/Hospital Infantil Sabara, International Life Science Institute of Argentina, Universidad de Costa Rica, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Universidad Central de Venezuela (CENDES-UCV)/Fundación Bengoa, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, and Instituto de Investigación Nutricional de Peru. This paper presents independent research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the acknowledged institutions. The funding sponsors had no role in study design; the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.F., conceived, designed, and helped to write and revise the manuscript; I.K., G.G., A.R., L.Y.C., M.Y.G., M.H.-C., M.F., were responsible for coordinating the study, contributed to the intellectual content, and revise the manuscript, C.C.-M., C.D., M.R.L.-D., M.P., A.M., P.M., R.F.C., A.C.B.L., C.F.-V., P.F.H., interpreted the data, helped to write and revise the manuscript. All authors contributed to the study design, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferrari, G., Cristi-Montero, C., Drenowatz, C. et al. Meeting 24-h movement guidelines and markers of adiposity in adults from eight Latin America countries: the ELANS study. Sci Rep 12, 11382 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15504-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15504-z

This article is cited by

-

Prevalence and association of compliance with the Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines with sociodemographic aspects in Brazilian adults: a cross-sectional epidemiological study

BMC Public Health (2024)

-

Movement Behaviors and Mental Health of Catholic Priests in the Eastern United States

Journal of Religion and Health (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.