Abstract

Approximately one third of children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS) carry pathogenic variants in one of the many associated genes. The WT1 gene coding for the WT1 transcription factor is among the most frequently affected genes. Cases from the Czech national SRNS database were sequenced for exons 8 and 9 of the WT1 gene. Eight distinct exonic WT1 variants in nine children were found. Three children presented with isolated SRNS, while the other six manifested with additional features. To analyze the impact of WT1 genetic variants, wild type and mutant WT1 proteins were prepared and the DNA-binding affinity of these proteins to the target EGR1 sequence was measured by microscale thermophoresis. Three WT1 mutants showed significantly decreased DNA-binding affinity (p.Arg439Pro, p.His450Arg and p.Arg463Ter), another three mutants showed significantly increased binding affinity (p.Gln447Pro, p.Asp469Asn and p.His474Arg), and the two remaining mutants (p.Cys433Tyr and p.Arg467Trp) showed no change of DNA-binding affinity. The protein products of WT1 pathogenic variants had variable DNA-binding affinity, and no clear correlation with the clinical symptoms of the patients. Further research is needed to clarify the mechanisms of action of the distinct WT1 mutants; this could potentially lead to individualized treatment of a so far unfavourable disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a kidney disease caused by increased permeability of the glomerular filtration membrane. Among the most important building blocks of the membrane are podocytes, disturbances of which play a major role in disease pathophysiology1. NS is one of the most common glomerulopathies in children, with an incidence estimated to be 1:25,000 children/year2. According to the clinical and laboratory response to an initial four-week long steroid treatment, patients are divided into steroid-sensitive or steroid-resistant cases (about 20% of children)3. Children with the steroid-resistant NS (SRNS) are at high risk of progression to end-stage renal disease and increased mortality4. Therefore, research clarifying the causes of SRNS and potentially allowing for targeted and personalized treatment is needed to improve such children's prognosis and quality of life.

More than 50 genes have been found to be associated with SRNS to date, and about 30% of children with SRNS carry pathogenic variants in one of these genes5,6. The WT1 gene, one of the most frequently mutated5,6, encodes a transcription factor that is important for normal urogenital development, proper formation of nephrons and the maintenance of podocyte function7,8. The pathogenic variants of WT1may be associated with isolated SRNS cases, but also with SRNS cases that additionally present with urogenital malformations and cancer, and a worse prognosis9.

To bind the DNA, WT1 uses the zinc-finger domains (ZFs)10. The EGR1 consensus sequence was the very first DNA sequence found to be targeted by WT111 and is present in the regulatory regions of many genes directed by the WT17,12. Interestingly, almost all exonic pathogenic variants of the WT1 gene are located in exons 8 and 9 that encode for ZFs 2 and 313. Therefore, it is likely that structural alterations of these ZFs may affect the binding affinity between the WT1 protein and EGR1 DNA sequence, potentially leading to change in the transcriptional activity of the protein.

In this functional study, we aimed to describe the DNA-binding affinity of wild type and mutant WT1 proteins selected based on the WT1 exonic variants found in Czech children with SRNS. These WT1 mutants were recombinantly produced, purified, and their EGR1 binding affinity assessed by a novel molecular interaction analysis method, microscale thermophoresis.

Results

Clinical, laboratory and genetic characteristics of children with WT1 pathogenic variants

Important clinical data for the cases with SRNS are shown in Table 1. The majority of cases (78%) manifested the disease within the first year of life (infantile NS), with only two patients manifesting later at preschool age (median: 5.0 months, min: 8 days, max: 4.2 years). The most frequent symptoms at disease onset were limb and/or facial edema (56% of patients), hypertension (44%) and hematuria (44%). Three (33%) patients had SRNS without any other renal or extrarenal disorders. Three patients (33%, two boys and one girl) had features of Denys-Drash syndrome, i.e. presented SRNS with nephroblastoma (Wilms tumor) and, in the two males, disorders of sex development (cryptorchism). One patient presented with SRNS and hypospadia and a cleft scrotum. The remaining two patients were biamnial monochorionic twins and presented with SRNS and stenosis of the pulmonary artery. The progression to end-stage renal disease was observed in all cases with variable age at presentation ranging from birth to 7.8 years (median 8.0 months). Kidney transplantation was performed in three patients (33%), who are the only patients currently still alive (total mortality was 67%). None of the patients presented with oligohydramnion. Molecular genetic analysis revealed eight different heterozygous WT1 variants in the nine children with SRNS. All of these variants were previously described in clinical case reports, however mostly without performing a proper functional study (see Table 2).

WT1 protein binding affinity to EGR1 DNA motif

The affinity curves and dissociation constants (Kds) for each of the WT1 proteins are presented in Fig. 1 and Table 2, respectively. Three WT1 mutants (p.Arg439Pro, p.His450Arg and p.Arg463Ter) showed significantly reduced binding affinity compared to the wild type WT1 protein (all three p < 0.01), whereas three other WT1 mutants (p.Gln447Pro, p.Asp469Asn and p.His474Arg) had increased binding affinity compared to the wild type WT1 protein (all three p < 0.01). In two other WT1 mutants (p.Cys433Tyr and p.Arg467Trp) the analysis did not reveal a statistically significant difference in the binding affinity compared to the wild type WT1 protein. The group of patients studied was too heterogeneous to perform any analyses exploring the association between binding affinity and clinical phenotype. There was no apparent segregation of distinct clinical phenotypes of the cases based on the DNA-binding affinity of WT1 mutants.

Binding affinity curves of all tested WT1 proteins. The relative amount of WT1 protein bound to the EGR1 DNA motif (fraction bound, y axis) analyzed by microscale thermophoresis. With increasing protein concentration (x axis) the bond becomes saturated (y axis). Shift to the left from the wild type (dark blue) reflects an increased binding affinity, while shift to the right means a decreased affinity. Bovine serum albumin (purple) was used as a negative control. All proteins measured in triplicates.

To improve our understanding of the link between the DNA-binding affinity of WT1 mutants and the expression of target genes, we performed reporter luciferase assay. Actin gene (ACTN1) was identified to be abundantly expressed in kidney according to Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000072110-ACTN1/tissue) and also contains WT1-specific binding site in its promoter, very close to the transcription start site8, thus posing a feasible target gene. Two representative WT1 mutants were selected (p.Gln447Pro and p.His450Arg, the highest and lowest binding affinity in the MST assay, respectively). The luciferase assay results showed that both WT1 mutant proteins significantly increased ACTN1 expression compared to WT1 wild type protein (Fig. 2).

Differential ACTN1 gene expression assessed by luciferase reporter assay. The effect of WT1 protein variants on ACTN1 gene expression assessed by luciferase reporter assay. Both WT1 mutant proteins significantly enhanced ACTN1 expression. The firefly luminescence values were normalized to background (negative control, i.e. vector free HEK293 cells) and to Renilla luminescence to adjust for variance in transfection.

Discussion

This functional in vitro study described the DNA-binding affinity of mutated forms of transcription factor WT1 found in the national cohort of children with SRNS. This might open up a pathway to elucidating the mechanism of action and, consequently, to targeted individualized treatment of the disease, which currently has a poor prognosis and high mortality rate.

Is WT1-pathogenic variant-caused SRNS distinguishable from other monogenic SRNS cases?

While edema, a diagnostic criterion of NS, was missing in 44% (4/9) of the studied patients with exonic WT1 variants, hypertension, a hugely non-specific symptom, was also detected in 44% (4/9) of these patients. These observations were in agreement with a unique genotype–phenotype study by Lipska et al., where edema was missing in 35% (14/40) and hypertension was noted in 50% (20/40) of patients with SRNS and pathogenic exonic WT1 variants14. Both numbers were much larger in the SRNS cases caused by the WT1 pathogenic variants compared to the non-WT1 SRNS cases14. Only three patients in the present study (33%, all girls) were classified as “isolated SRNS” cases, i.e. did not show any other renal or extra-renal disorders or symptoms. The frequency (28%) as well as the sex (females only) of these “isolated SRNS” cases was also in agreement with the study by Lipska et al.14.

Pathogenic variants in the WT1 gene were found to be associated with Denys-Drash syndrome, in which SRNS is accompanied by nephroblastoma, disorder of sex development and testicular/ovarian cancer15. In the present study, three patients (33%, two boys and one girl) had features of Denys-Drash syndrome. Both boys with Denys-Drash syndrome manifested with SRNS, cryptorchism and nephroblastoma and the girl had SRNS and nephroblastoma without any congenital defects of the genital system. This is in agreement with the Denys-Drash syndrome phenotype in females who usually do not present with disorder of sex development16. Cell culture studies showed that WT1 targets the SRY gene, which encodes the testis-determining factor on chromosome Y17. Mutant WT1 proteins transcribed from the WT1 gene that contained the pathogenic variants found in Denys-Drash syndrome cases failed to activate the SRY promoter in a reporter gene assay, whereas the wild type WT1 protein was able to do so17. The SRY activation is important for the development of testes and thus determines the male sex18; WT1 variants may thus cause impairment of proper male sex development, which also explains why the disorder of sex development in Denys-Drash syndrome is rather male specific.

Besides the disorder of sex development in males, Denys-Drash syndrome is also characterized by the presence of nephroblastoma (also called Wilms tumor) and testicular/ovarian cancer15. These cancer types do not occur in SRNS cases caused by genes other than WT15. It was observed that WT1 directly regulates factors DAX1 and SF1, both important in testicular and ovarian development19,20. Moreover, transgenic mouse embryos carrying homozygous WT1 pathogenic variant have shown abrogation of gonadal development21. Therefore, impairment of WT1-transcriptional activity may pose a risk factor for the development of testicular and ovarian cancer through the dysregulation of DAX1 and SF1 proteins. Similarly, the loss of WT1 affects Wnt signalling and IGF2 expression, both factors that are important for kidney development, and their dysregulation was found to be present in nephroblastomas22. However, approximately 40 different genes have been found to be associated with the development of nephroblastoma23 and testicular/ovarian cancer is also not a specific feature of Denys-Drash syndrome. Therefore, although the presence of nephroblastoma and/or gonadal cancer in SRNS cases strongly suggests that WT1 pathogenic variants are involved in the pathogenesis of the disease, the exact molecular mechanism remains to be elucidated.

Three other children with SRNS also additionally presented with distinct extra-renal features. The monochorionic biamnial twins carrying the p.Arg439Pro variant had a stenosis of pulmonary artery, which is a unique observation, as there has been no such a WT1–caused SRNS case published in the literature so far. During heart development, epithelial cells are released from the epicardium into the myocardium and transform into cardiovascular progenitor cells, which can differentiate into coronary wall smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, perivascular and cardiac interstitial fibroblasts or cardiomyocytes24,25. A key activator of the so called epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition process is the Snail factor, which is regulated by the WT1 protein24. The Snail factor has been found to be reduced in the WT1-knockout immortalized epicardial cells24. In addition, another study has found that WT1 together with its corepressor BASP1 inhibited the epithelial cell activator WNT4 in epicardial cells26. The epithelial cell activators act against the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition process and are important for the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition process (typical for kidney development)27. Therefore, decreased WT1 transcription activity present at a specific embryonic stage of heart development may well cause congenital heart defects due to the diminished number of progenitor cardiovascular cells.

The last patient manifested with SRNS and a cleft scrotum and hypospadia. This patient died 3 weeks after birth (two weeks after the diagnosis was confirmed). Some patients with Denys-Drash syndrome develop nephroblastoma months after the manifestation of SRNS15. It may thus be speculated that the patient could have developed nephroblastoma later had he survived longer, which would classify him as another case of Denys-Drash syndrome in this case series.

In summary, children with SRNS and a pathogenic variant in the WT1 gene frequently presented with hypertension and a lack of edemas. A substantial proportion of these patients concurrently manifested disorder of sex development and/or nephroblastoma. These features make this group of patients distinguishable from the other monogenic causes of SRNS.

The effect of WT1 variants on the DNA-binding affinity of its protein products

As all of the patients in this study carried WT1 exonic variants (exons 8 and 9) potentially affecting the structure of the WT1 ZFs 2 and 3, which together with ZF4 have been shown to be responsible for specific DNA sequence recognition10, one could expect that the mutations would negatively influence the binding affinity of the protein to its target DNA sequence13. Interestingly, three different trends in target DNA binding (reduced, wild type-like and enhanced) were observed for the distinct WT1 variants.

Decreased DNA-binding affinity of the WT1 protein mutants leads to reduced activity of several genes, i.e. WNT426. The WNT4 is the main cell-differentiation factor that drives the mesenchyme-epithelial transition in nephrogenesis28. During this process, the metanephric mesenchyme, in close cooperation with the neighboring ureteric bud, induces the formation of renal epithelium and, later, the nephrons28. It is known that WT1 expression in metanephric mesenchyme precedes WNT4 expression, and also that the WNT4 gene carries a specific WT1 DNA binding domain26. Moreover, in a cell expression study it has been verified that knockout of WT1 in mouse embryonic kidney mesenchymal cells is associated with the loss of WNT4 expression26. Thus, reduced DNA-binding and the related decrease in the transcriptional activity of WT1 may negatively influence kidney development through abnormal nephron formation. The fetuses of the WT1 null mouse model did not develop kidneys, gonads or spleen, and died at mid-gestation due to defective coronary vasculature21. A transgenic adult mouse model with a doxycycline-inducible podocyte-specific knockout of WT1 has shown progressive albuminuria, FSGS on kidney histological sections and disruption of podocyte structure accompanied by loss of podocalyxin and nephrin, i.e. proteins essential for the glomerular filtration membrane29,30. WT1 ortholog knockout in zebrafish embryo has shown pericardial and yolk edema, reduction of kidney size and damage of podocyte foot processes with a poorly developed glomerular filtration membrane31. These features were rescued by injection of human wild type WT1 mRNA but not with the WT1 pathogenic variant31. Moreover, HEK293 cells transfected with a WT1 exonic variant demonstrated downregulation of nephrin and synaptopodin (an important factor for inter-podocyte communication)31. Altogether, these studies suggest that the decreased DNA-binding affinity of several of our WT1 mutants may cause the SRNS through the structural and functional impairment of podocytes.

In three patients the WT1 mutants (p.Gln447Pro, p.Asp469Asn and p.His474Arg) showed an increased binding affinity to the EGR1 DNA domain when compared to the wild type WT1 protein. Murine myeloblastic leukemia cells transfected with the WT1 gene and injected into mice has shown a significant reduction of tumorigenesis compared to none-transfected leukemic cells32. WT1 has also induced apoptosis of the primary osteosarcoma cells through activation of the proapoptotic gene Bak33. In contrast, overexpression of WT1 has been observed in nephroblastoma, breast and colon cancer or acute myeloid leukemia34,35. These studies suggest that the WT1 transcription factor may act as both a tumor suppressor and tumor inducer, probably based on concentration and cellular microenvironmental conditions. While under normal conditions WT1 is necessary for proper podocyte differentiation31, we can speculate that the same factor may cause podocyte damage through increased transcriptional activity, if the WT1 sequence variant leads to production of WT1 protein with augmented DNA-binding affinity. Unfortunately, this hypothesis cannot be confirmed, because there have been no studies published focusing on the impact of WT1 overexpression on kidney development.

The proof-of-concept functional study employing a luciferase assay demonstrated that both WT1 protein mutant with the highest DNA-binding affinity (p.Gln447Pro) as well as the mutant with the lowest affinity (p.His450Arg) enhanced ACTN1 gene expression, compared to the effect of the WT1 wild type protein. It has been well established that gene transcription in eukaryotic organisms is under combinatorial control of multiple transcription factors and that also conformational changes, not just the DNA-binding itself, significantly influence the assembly and proper function of the general transcription factors and RNA polymerase machinery36,37. Therefore, our study shows that alterations in DNA-binding affinity of WT1 protein mutants do not really predict changes in target gene expression and suggest it might be the conformational WT1 protein changes that affect assembly of the transcription machinery complex.

There were two patients with WT1 variants (p.Cys433Tyr and p.Arg467Trp) who showed no change in the DNA-binding affinity of the resulting WT1 mutants when compared to the affinity of the wild type WT1 protein. Both variants have previously been described as causing syndromic (Denys-Drash syndrome) and also isolated SRNS9,38. The WT1 protein has two important isoforms. The WT1 KTS minus isoform is the canonical transcription factor that has much higher binding affinity to the target DNA domain than the WT1 KTS plus isoform34. The WT1 KTS plus isoform is formed by alternative RNA splicing, which results in the addition of lysine (K), threonine (T) and serine (S) between ZFs 3 and 4. The KTS insertion changes the rigid ZF conformation, which is thus more flexible and partly prevents ZF4 from its DNA binding34. As it has been shown that the WT1 KTS plus isoform is capable of interaction with some RNA binding proteins, and thus can be employed in the splicing machinery or in the regulation of mRNA stability34,39, we cannot exclude that the pathogenic effect of both variants has other mechanism than alteration of the DNA binding. However, only the WT1 KTS minus isoforms were produced in this study, which was thus not designed to test the molecular interaction of the different WT1 isoforms. Another possible mechanism may be the interaction between WT1 and its cofactors (i.e., p53, STAT3, BASP1), which modulate WT1 transcription activity34,40. If the two WT1 variants impaired the cofactor-binding site but retained the DNA-binding site of the WT1 mutant, no change would be seen in the binding assay despite the alteration in its transcriptional activity. As the molecular interaction assay was not designed to check for the binding between the distinct WT1 mutants and the WT1 transcriptional cofactors, this possibility can neither be confirmed nor refuted. Although SRNS is known to be a monogenic disease, it may also be that there are risk variants or polymorphisms in the WT1 cofactors that could change the transcriptional activity of the mutant WT1, similarly to the situation in patients with atypical haemolytic uremic syndrome41.

In conclusion, this is the first study describing the DNA-binding affinity changes of WT1 mutants found in a national cohort of children with SRNS using a novel molecular interaction analysis method, microscale thermophoresis. Our observations confirm that children with SRNS carrying WT1 exonic variants quite often present with hypertension and lack edemas, which may help to distinguish them from patients with the other monogenic causes of SRNS. The experimental study found that the distinct WT1 mutants present with variable change in the DNA-binding affinity. Moreover, DNA-binding affinity did not correspond to target gene expression. Multiple factor combinatorial control of gene transcription and conformational changes of WT1 mutants possibly affecting the assembly of transcription machinery complex could explain the lack of clear link between WT1 gene mutation, DNA-binding of its protein product and target gene expression. There was no clear association between the change in the DNA-binding affinity and the clinical phenotype. Although evidence is discussed regarding the possible mechanisms of action of the variable DNA-binding affinity and the multisystemic effects of WT1 mutants, there is a lack of detailed knowledge on how distinct WT1 variants cause the disease. To enable personalized treatment and improve the unfavourable prognosis of the patients, further investigation is needed to explore the mechanisms of action of the distinct WT1 mutants.

Methods

Identification of WT1 gene variants

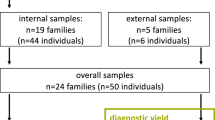

Within the Czech national database of children with SRNS, a total of nine WT1 gene positive cases were identified from eight unrelated families (two patients were monochorionic biamnial twins). The study was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee of Motol University Hospital and we confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study subjects and their guardians provided their informed consent in writing. All cases had a negative family history of kidney disease and were born from non-consanguineous marriages. Seven patients were included in our previously published study of the genetic causes of SRNS6, where a two-tiered approach was implemented (Sanger sequencing of NPHS1, NPHS2 and WT1 genes as a first step, and then, when negative, next-generation sequencing of a 48-gene-panel). Since the publication of that paper, two further patients have been identified by routine Sanger sequencing of the four most frequently mutated genes in SRNS cases (i.e. NPHS1, NPHS2, WT1 and NUP93). The clinical significance of the identified variants was assessed using well-known prediction programs (Mutation Taster, Provean, Polyphen-2, Human Splicing Finder, UMD predictor and CADD scores). The Human Gene Mutation Database42 was searched for previous descriptions of the variants, and the NCBI dbSNP for global minor allele frequencies (exclusion of common variants with a frequency of 1% or more in healthy populations found in 1000 Genomes, GnomAD and NHLBI ESP Genomes). Current standards as published by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics were followed to evaluate variant pathogenicity. A freely available online software tool that implements these standards was used for the evaluation of the revealed variants43,44.

Preparation of WT1 proteins

All the preparation methods are described in detail in the Supplementary material. The DNA manipulations were carried out using standard subcloning techniques, and plasmids were propagated in E. coli DH5α45,46. The (–KTS) isoform of the WT1 gene was obtained by reverse transcription of total RNA isolated from A549 cells using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagene). The E. coli BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus RIL strain was transformed by wild type or each mutant WT1 plasmid by using heat-shock. The isolation of WT1 proteins from the bacterial pellet was achieved by using buffers with increasing concentrations of sodium chloride. The prepared sample was subjected to fast liquid protein chromatography (FPLC, ÄKTA pure protein purification system with Unicorn software) to separate the proteins according their ion charge (HiPrep SP FF 16/10 by Cytiva, strong cation exchange chromatography column). The achieved protein was then separated using high-resolution preparative gel filtration chromatography (HiLoad 26/600 Superdex 200 pg column by Cytiva). The concentration of purified WT1 proteins was calculated and before the MST experiment the samples were concentrated (see Supplementary material for details). The sample buffer was exchanged for the MST binding assay buffer and the final assay concentration was calculated.

Binding analysis

Microscale thermophoresis (MST) was performed using a Monolith NT.115 instrument (NanoTemper Technologies) and its built-in software (MO.Control software, NanoTemper Technologies), which includes an intuitive and interactive protocol guidance. The target EGR1 DNA sequence was labelled by cyanine 5 ([Cyanine5]GTGGAGGCGGCGGGGGCGGCAGCAACAG produced by Sigma Aldrich) to detect the thermophoresis of the oligo. The assay concentration of the DNA was set up at 80 nM, while the starting (highest) concentration of the protein ranged from 1 to 4 mM. The binding affinity analysis was performed using standard MST capillaries, 20% excitation power (Nano – RED) and medium MST power at room temperature. After optimizing the binding assay buffer (final composition: 50 mM Na2HPO4.12H2O, 150 mM NaCl and 0.005% Tween), satisfactory MST traces were achieved (Fig. 3). The affinity curves for distinct WT1 protein mutants (each measured thrice in a row) were produced by MO.Affinity Analysis software (NanoTemper Technologies).

Satisfactory MST traces achieved with optimized MST assay buffer. Left: The curves represent the decrease in fluorescence over time after the application of heat induced by laser. The purple strip marks the baseline while the red strip indicates the point of interest. Right: Normalized fluorescence change in samples of DNA and serially diluted protein. If binding is present, an ”S-affinity curve” is seen and the dissociation constant (dashed line) may be calculated.

Luciferase assay

HEK293 cells were transfected by luciferase reporter gene vector containing ACTN1 promoter and WT1 wild type, WT1 p.Gln447Pro or WT1 p.His450Arg vectors. All samples were prepared in triplicates and the assay was repeated in six independent measurements. All details of the plasmid production, transfection of HEK293 cells and luciferase assay are available in Supplementary information.

Statistics

The average dissociation constant (Kd) was calculated from triplicates of each measured WT1 protein and the statistical significance of the difference in mean Kds was then verified by a two-sample t-test computed in R software47.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee of Motol University Hospital.The study subjects and their guardians provided their informed consent in writing.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Torban, E. et al. From podocyte biology to novel cures for glomerular disease. Kidney Int. 96(4), 850–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.05.015 (2019).

Dossier, C. et al. Epidemiology of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children: Endemic or epidemic?. Pediat. Nephrol. 31(12), 2299–2308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-016-3509-z (2016).

McKinney, P. A., Feltbower, R. G., Brocklebank, J. T. & Fitzpatrick, M. M. Time trends and ethnic patterns of childhood nephrotic syndrome in Yorkshire, UK. Pediat. Nephrol. 16(12), 1040–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004670100021 (2001).

Tullus, K., Webb, H. & Bagga, A. Management of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children and adolescents. Lancet Child Adolescent Health 2(12), 880–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30283-9 (2018).

Bierzynska, A. et al. Genomic and clinical profiling of a national nephrotic syndrome cohort advocates a precision medicine approach to disease management. Kidney Int. 91(4), 937–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.013 (2017).

Bezdíčka, M. et al. Genetic diagnosis of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in a longitudinal collection of Czech and Slovak patients: a high proportion of causative variants in NUP93. Pediat. Nephrol. 33(8), 1347–1363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-018-3950-2 (2018).

Dong, L. et al. Integration of Cistromic and Transcriptomic Analyses Identifies Nphs2, Mafb, and Magi2 as Wilms’ Tumor 1 Target Genes in Podocyte Differentiation and Maintenance. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26(9), 2118–2128. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2014080819 (2015).

Hartwig, S. et al. Genomic characterization of Wilms’ tumor suppressor 1 targets in nephron progenitor cells during kidney development. Development 137(7), 1189–1203. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.045732 (2010).

Pelletier, J. et al. Germline mutations in the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene are associated with abnormal urogenital development in Denys-Drash syndrome. Cell 67(2), 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(91)90194-4 (1991).

Stoll, R. et al. Structure of the Wilms tumor suppressor protein zinc finger domain bound to DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 372(5), 1227–1245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.017 (2007).

Rauscher, F. J. 3rd., Morris, J. F., Tournay, O. E., Cook, D. M. & Curran, T. Binding of the Wilms’ tumor locus zinc finger protein to the EGR-1 consensus sequence. Science 250(4985), 1259–1262. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2244209 (1990).

Kann, M. et al. Genome-wide analysis of Wilms’ tumor 1-controlled gene expression in podocytes reveals key regulatory mechanisms. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26(9), 2097–2104. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2014090940 (2015).

Mucha, B. et al. Mutations in the Wilms’ tumor 1 gene cause isolated steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome and occur in exons 8 and 9. Pediat. Res. 59(2), 325–331. https://doi.org/10.1203/01.pdr.0000196717.94518.f0 (2006).

Lipska, B. S. et al. Genotype-phenotype associations in WT1 glomerulopathy. Kidney Int. 85(5), 1169–1178. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2013.519 (2014).

Roca, N. et al. Long-term outcome in a case series of Denys-Drash syndrome. Clin Kidney J12(6), 836–839. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfz022 (2019).

Swiatecka-Urban, A., Mokrzycki, M. H., Kaskel, F., Da Silva, F. & Denamur, E. Novel WT1 mutation (C388Y) in a female child with Denys-Drash syndrome. Pediat. Nephrol. 16(8), 627–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004670100626 (2001).

Hossain, A. & Saunders, G. F. The human sex-determining gene SRY is a direct target of WT1. J. Biol. Chem. 276(20), 16817–16823. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M009056200 (2001).

Larney, C., Bailey, T. L. & Koopman, P. Switching on sex: Transcriptional regulation of the testis-determining gene Sry. Development 141(11), 2195–2205. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.107052 (2014).

Kim, J. et al. The Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene (wt1) product regulates Dax-1 gene expression during gonadal differentiation. Mol. Cell Biol. 19(3), 2289–2299. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.19.3.2289 (1999).

Wilhelm, D. & Englert, C. The Wilms tumor suppressor WT1 regulates early gonad development by activation of Sf1. Genes Dev. 16(14), 1839–1851. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.220102 (2002).

Kreidberg, J. A. et al. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell 74(4), 679–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(93)90515-r (1993).

Gadd, S. et al. Clinically relevant subsets identified by gene expression patterns support a revised ontogenic model of Wilms tumor: a Children’s Oncology Group Study. Neoplasia 14(8), 742–756. https://doi.org/10.1593/neo.12714 (2012).

Treger, T. D., Chowdhury, T., Pritchard-Jones, K. & Behjati, S. The genetic changes of Wilms tumour. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15(4), 240–251. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-019-0112-0 (2019).

Martínez-Estrada, O. M. et al. Wt1 is required for cardiovascular progenitor cell formation through transcriptional control of Snail and E-cadherin. Nat. Genet. 42(1), 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.494 (2010).

Thiery, J. P., Acloque, H., Huang, R. Y. & Nieto, M. A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 139(5), 871–890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007 (2009).

Essafi, A. et al. A wt1-controlled chromatin switching mechanism underpins tissue-specific wnt4 activation and repression. Dev. Cell 21(3), 559–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.014 (2011).

Costantini, F. & Kopan, R. Patterning a complex organ: Branching morphogenesis and nephron segmentation in kidney development. Dev. Cell 18(5), 698–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2010.04.008 (2010).

Stark, K., Vainio, S., Vassileva, G. & McMahon, A. P. Epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney regulated by Wnt-4. Nature 372(6507), 679–683. https://doi.org/10.1038/372679a0 (1994).

Gebeshuber, C. A. et al. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis is induced by microRNA-193a and its downregulation of WT1. Nat. Med. 19(4), 481–487. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3142 (2013).

Chau, Y.-Y. et al. Acute multiple organ failure in adult mice deleted for the developmental regulator Wt1. PLoS Genet. 7(12), e1002404–e1002404. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002404 (2011).

Hall, G. et al. A novel missense mutation of Wilms’ Tumor 1 causes autosomal dominant FSGS. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26(4), 831–843. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2013101053 (2015).

Smith, S. I., Down, M., Boyd, A. W. & Li, C. L. Expression of the Wilms’ tumor suppressor gene, WT1, reduces the tumorigenicity of the leukemic cell line M1 in C.B-17 scid/scid mice. Cancer Res. 60(4), 808–814 (2000).

Loeb, D. M. WT1 influences apoptosis through transcriptional regulation of Bcl-2 family members. Cell Cycle 5(12), 1249–1253. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.5.12.2807 (2006).

Ullmark, T., Montano, G. & Gullberg, U. DNA and RNA binding by the Wilms’ tumour gene 1 (WT1) protein +KTS and -KTS isoforms-From initial observations to recent global genomic analyses. Eur. J. Haematol. 100(3), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.13010 (2018).

Koesters, R. et al. WT1 is a tumor-associated antigen in colon cancer that can be recognized by in vitro stimulated cytotoxic T cells. Int. J. Cancer 109(3), 385–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.11721 (2004).

He, B. et al. Lmx1b and FoxC combinatorially regulate podocin expression in podocytes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 25(12), 2764–2777. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2012080823 (2014).

Reményi, A., Schöler, H. R. & Wilmanns, M. Combinatorial control of gene expression. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11(9), 812–815. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb820 (2004).

Clarkson, P. A. et al. Mutational screening of the Wilms’s tumour gene, WT1, in males with genital abnormalities. J. Med. Genet. 30(9), 767–772. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.30.9.767 (1993).

Bharathavikru, R. et al. Transcription factor Wilms’ tumor 1 regulates developmental RNAs through 3’ UTR interaction. Genes Dev. 31(4), 347–352. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.291500.116 (2017).

Toska, E. & Roberts, S. G. Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation by WT1 (Wilms’ tumour 1). Biochem J461(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj20131587 (2014).

Štolbová, Š et al. Molecular basis and outcomes of atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome in Czech children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 179(11), 1739–1750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-020-03666-9 (2020).

Stenson, P. D. et al. The human gene mutation database: Towards a comprehensive repository of inherited mutation data for medical research, genetic diagnosis and next-generation sequencing studies. Hum. Genet. 136(6), 665–677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-017-1779-6 (2017).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17(5), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.30 (2015).

Kleinberger, J., Maloney, K. A., Pollin, T. I. & Jeng, L. J. An openly available online tool for implementing the ACMG/AMP standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants. Genet. Med. 18(11), 1165. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.13 (2016).

Dostálková, A. et al. In Vitro Quantification of the Effects of IP6 and Other Small Polyanions on Immature HIV-1 Particle Assembly and Core Stability. J. Virol. 94(20), 1. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00991-20 (2020).

Füzik, T., Ulbrich, P. & Ruml, T. Efficient Mutagenesis Independent of Ligation (EMILI). J. Microbiol. Methods 106, 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2014.08.003 (2014).

Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2014). URL http://www.R-project.org/.

Fencl, F. et al. Discordant expression of a new WT1 gene mutation in a family with monozygotic twins presenting with congenital nephrotic syndrome. Eur. J. Pediatr. 171(1), 121–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-011-1497-3 (2012).

Nordenskjöld, A., Friedman, E. & Anvret, M. WT1 mutations in patients with Denys-Drash syndrome: a novel mutation in exon 8 and paternal allele origin. Hum. Genet. 93(2), 115–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00210593 (1994).

Schumacher, V. et al. Correlation of germ-line mutations and two-hit inactivation of the WT1 gene with Wilms tumors of stromal-predominant histology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. US A94(8), 3972–3977. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.8.3972 (1997).

Xiong, H. Y. et al. RNA splicing: The human splicing code reveals new insights into the genetic determinants of disease. Science 347(6218), 1206. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254806 (2015).

Barrera, L. A. et al. Survey of variation in human transcription factors reveals prevalent DNA binding changes. Science 351(6280), 1450–1454. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad2257 (2016).

Funding

This study was supported by Charles University, project GA UK No. 384119, and in part by the Project for the Conceptual Development of Research Organization, Motol University Hospital (Ministry of Health, Czech Republic; 00064203) and the Research and Development for Innovation Operational Programme (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Czech Republic, co-financed by the EU; CZ.1.05/4.1.00/16.0337).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B. prepared WT1 proteins, performed MST, luciferase reporter assay, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. I.K. prepared the plasmids and performed the site-directed mutagenesis. A.D. and F.K. helped with the production of the WT1 proteins. M.R. designed and supervised the protein expression studies. T.S., K.V., F.F. and J.Z. cared for the patients and collected their DNA. O.S. designed the whole project, secured funding, supervised the experimental work, analyzed the data and helped with the draft of the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bezdicka, M., Kaufman, F., Krizova, I. et al. Alteration in DNA-binding affinity of Wilms tumor 1 protein due to WT1 genetic variants associated with steroid - resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. Sci Rep 12, 8704 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12760-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12760-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.