Abstract

Mind wandering (MW) is commonly observable in daily life. Early studies established an association between motivation and MW at the trait level using a questionnaire survey. Considering that the mechanism of state-level association between them is known, this study was conducted to replicate the trait-level association and determine its possible mechanisms. Two independent samples were analysed using several questionnaires, which included motivation and MW. General one- and multi-dimensional scales were administered for both variables. Besides the successful replication of the significant association between motivation and MW at the trait level, we found that people with low levels of executive function experience high rates of spontaneous MW. This finding indicates that the underlying mechanism of trait-level association is the executive failure hypothesis, which postulates that a failure of executive control during task-related objectives evokes MW. Further, the motivation–MW relationship exhibits a different psychological basis at the state and trait levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mind wandering (MW) is an experience wherein the mind drifts away from the task at hand towards unrelated inner thoughts, which may occur for 50% of the waking time1. In contrast to traditional cognitive psychological research, the MW concept focuses on subjective internal thoughts and feelings unrelated to external tasks and on the shift between them. This study uses MW as a general umbrella term, although it may include task-unrelated, stimulus-independent and self-generated thoughts2,3,4,5.

In the literature, motivation has attracted attention because of its association with MW. Previous studies have found a significant association between low levels of motivation and the occurrence of MW during task execution6,7,8. The intentionality of MW can explain the underlying mechanism of this state-level association as follows9,10. Experimental psychologists predict that participants would be moderately motivated to complete a laboratory task; however, in reality, participants may not be motivated towards performing the task. Instead, representative tasks used in MW studies are intended to demotivate participants. In these trivial, boring tasks, participants became unmotivated, thus causing their minds to wander deliberately6,7,11. Similarly a redundant encoding of information (i.e. re-reading), which may be uneventful and demotivating, causes deliberate MW but not spontaneous MW12.

In contrast to this state-level finding, Kawagoe et al.13 verified the aforementioned relationship at the depositional and/or temperament trait level, where individuals with low levels of trait motivation were found to experience MW more regularly in their daily life. However, the psychological mechanism underlying this trait-level association remains unknown. Thus, the current study investigated whether this psychological mechanism may apply to the trait-level association between motivation and MW. One possibility is that humans tend to intentionally let their minds wander when confronted with boring tasks and/or situations in daily life (i.e. trait level), as in the case of state level.

A variable that possibly promotes the association between motivation and MW is executive function. Throughout the process of uncovering the phenomenological characteristics of MW, scholars have investigated its association with other psychological features, such as attentional/executive control, meta-cognition and problem solving, finding that such a higher-order cognitive function is significantly correlated with MW4,5,14, although the directionality of the associations varies from negative3,6,15 to positive2,4, depending on the context wherein MW is measured7. For example, the executive function works to constrain attention only to task-relevant information in a demanding situation and may result in a negative association, while in an undemanding external task, individuals with greater cognitive ability could let their mind wander to task-irrelevant information in an adaptive manner that may cause a positive association. In trait level, accordingly, executive function could exhibit both ways of association with MW because there are tons of tasks with various degrees of difficulties in daily life, which is still unknown. It is reasonable to inspect the motivation–MW association via an index of executive function. Simultaneously, a deterioration in executive function can cause a clinical level of amotivation16,17,18, whose association can be observed in healthy individuals19,20.

This study views motivation as a continuum to the clinical state of apathy. In clinical populations, people who are consistently unmotivated are deemed apathetic, defined as the lack of motivation that is not attributable to a diminished level of consciousness, cognitive impairment or emotional distress16,17. As per the definition, this concept could be applied to healthy individuals19,20, especially when a comprehensive, simplified scale to assess general motivation in daily life is lacking. This is because traditionally, motivation has been understood as a state that is assessed in many fields, including psychology, during specific situations using explicit goals, such as provocation using various forms of incentives (for a review, see Braver et al.21). Previous clinical studies have indicated that apathy is multi-dimensional and can be grouped as executive, emotional and initiation-related types17,18. For example, the executive type of apathy refers to amotivation for planning, organisation or attention, which is apparently owing to the deterioration of executive function. Thus, we utilised the dimensional apathy scale (DAS), which comprises the executive (dasEx), emotional (dasEm) and behavioural/cognitive initiation (dasIni) sub-factors of apathy18. This study aims to investigate whether the executive type of amotivation is specifically associated with MW. Hereafter, we use the term (a)motivation instead of apathy in order to not focus on the participants’ clinical aspects.

In summary, the current study aims to uncover the psychological mechanism underlying the trait-level association by considering the intentionality of MW and executive function. If the trait-level association between motivation and MW depends on the same mechanism for the state level, intentionality should affect the relationship wherein a deliberate type of MW has a stronger relationship with motivation than spontaneous MW. Alternatively, if the executive control is the key, the measurements related to executive function would mediate the motivation–MW relationship. To these ends, Study 1 first intends to determine whether replicating the significant association between motivation and MW at the trait level is confirmed by using an online survey. Further, this study adopts several mediation models besides simple correlation analyses wherein each component (i.e. spontaneous/deliberate components of MW, executive component of motivation and both) mediates the association between motivation and MW in general. Notably, although mediation analysis is used in this study, we could not assume the causality among the variables. We could only expect that the covariance between motivation and executive function could cause MW. In Study 2, another independent sample was used with the objective of conducting self-replication within the study to enhance the reliability of the findings in Study 1 (in which the executive function was assessed using a specialised measurement), that is, the effortful control scale (ECS)22,23 was used to promote the concept that executive function mediates the relationship between motivation and MW. Specifically, this study conducted mediation analyses to verify whether executive control (i.e. ECS) mediates the effect of motivation on MW.

Study 1

Participants

This study used an online survey. All participants were recruited via iBRIDGE Corporation, a data collection company, and are assumed to be Japanese based on their location. They were compensated by a small amount of ‘points’ set by the data collection company. One thousand participants (aged 20–69 years) were recruited with the objective of including 200 participants in every age group (i.e. 20–29, 30–39, and so on), which resulted in 1009 participants in total. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The appropriate ethics committee approved the study, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, as revised in 2008).

Three lure items (i.e. ‘Please select the most correct choice for this item’) were added to identify participants who answered without paying sufficient attention to the items. The study was concerned about a possible satisficing behaviour from the participants, which may contaminate the data24. Participants who failed to follow the instructions were excluded from the analyses. Finally, data from 587 participants were analysed (mean age = 47.3 ± 13.5 years; women = 301). The sample size met the rule of thumb for regression analysis, that is, 100 participants + 100 per predictor variable25,26.

Measurements

This study investigated the level of motivation (or apathy) and MW at the trait level. Two questionnaires were used to assess motivation and MW, namely, a one-dimensional scale and a multi-dimensional one.

Scales for motivation

Apathy scale (AS)

AS is a 14-item questionnaire that asks participants if they have experienced a lack of motivation27. Each item is scored from 0 to 3; the total scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating increased amotivation. AS is used worldwide, and it exhibits good validity and reliability. This study employed the Japanese version of the scale28. Sample items include the following: ‘Are you interested in learning new things?’ and ‘Do you have the energy for daily activities?’

Dimensional apathy scale (DAS)

DAS is used to assess apathy in a multi-dimensional manner18, using three dimensions, namely, executive, emotional and initiation, which are based on rigorous clinical and neurological observations17. Each dimension is assessed using eight items, with scores ranging from 0 to 3. In total, the sub-scores ranged from 0 to 24 for each dimension, with higher scores indicating higher levels of amotivation, which is similar to what holds for AS. We utilised the Japanese version of the scale29. Sample items for the executive, emotional and initiation subscales are as follows: ‘I find it hard to concentrate on things’, ‘Before I do something, I think about what others would feel about it’ and ‘I contact my friends’.

Scales for mind wandering

Mind wandering questionnaire (MWQ)

MWQ is a single-factor questionnaire that assesses an individual’s tendency towards MW30. MWQ comprises five items rated using a 6-point Likert-type scale. The total scores ranged from 5 to 50, with higher scores indicating higher levels of MW tendency. This study used the Japanese version of the scale31. A sample item is as follows: ‘I have difficulty maintaining focus on simple or repetitive work’.

Mind wandering: deliberate (MW-D) and spontaneous (MW-S)

MW-D and MW-S were used to assess MW with and without intention, respectively32. Each scale comprises four items rated using a 7-point Likert-type scale. Scores ranged from 4 to 28, with higher scores indicating increased MW tendency for each type. The Japanese versions of the scale were used33. Sample items include the following: ‘I allow my thoughts to wander on purpose’ (MW-D) and ‘I find my thoughts wandering spontaneously’ (MW-S).

Analyses

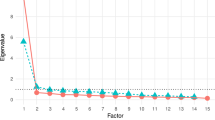

This study primarily used correlational analyses. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each correlation coefficient were listed. Although correlational analyses were conducted in a sequential manner, multiplicity was considered by using the Bonferroni correction given the number of possible combinations to strengthen the reliability of the results. To investigate the specificity of these associations, Fisher’s r to z transformation was used to statistically compare the correlation coefficients. Although skewness and kurtosis were within acceptable ranges (< |2|)34 (Tables 1 and 2), MW-D and MW-S seemingly intruded on the distribution of normality with a floor effect (Figs. S1 and S2). Therefore, supplemental non-parametric analyses were implemented for the correlations that included the two variables. Moreover, based on the results of the correlation, several mediation analyses were conducted to elucidate the structure of the current data. To investigate whether the sub-components (executive for motivation and spontaneous for MW) mediate the association between motivation and MW in general, the study set the independent and dependent variables as AS and MWQ, respectively. In Models 1 and 2, the mediators were MW-S and dasEx, respectively. In Model 3, MW-S and dasEx were simultaneously included. Besides the conventional z-test, bootstrapping (2,000 samples) was used to test the significance of the indirect effects, which does not require assuming normality of the sample distribution35. These non-nested models were compared via Vuong’s likelihood ratio tests36,37. The analyses and visualisation were performed using R (https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive information of the participants, which is visualised in Fig. S1. First, to replicate a previous report of the significant association between motivation and MW at the trait level13, this study employed correlation analysis and found that the replication was successful, where the lower the motivation, the higher the MW rates experienced at the trait level (AS-MWQ: r = 0.39 [95% CI 0.32–0.46], p < 0.001). Figure S3 presents the correlation coefficients among the variables.

To test the hypothesis that people who are unmotivated intentionally allow their minds to wander, this study assessed the correlations between AS and MW-D/S. A significant correlation was found between AS and MW-S (r = 0.25 [95% CI 0.18–0.33], p < 0.001) but not between AS and MW-D (r = 0.10 [95% CI 0.02–0.18], p = 0.248) (Fig. 1A). These correlation coefficients differed significantly (z = 4.69, p < 0.001). The second hypothesis, that is, the executive component will modulate the relationship between motivation and MW, was also tested. MWQ was significantly correlated with dasEx (r = 0.66 [95% CI 0.61–0.70], p < 0.001) but not with the other sub-components of DAS (dasEm: r = 0.00 [95% CI − 0.08 to 0.08], p = 0.988; dasIni: r = 0.09 [95% CI 0.01–0.17], p = 0.522) (Fig. 1B). This difference was also significant (zs > 12.3, ps < 0.001). As an additional analysis, non-parametric correlational analysis was conducted for measures whose distributions violated normality. This analysis did not influence the significance of the results, as shown in the Supplementary Material.

Scatter Plots of the Correlations Between Mind Wandering and Motivational Indices in Study 1. Note Data for non-significant correlations after multiple corrections are only shown by the 95% elliptical confidence region of the multivariate t-distribution. DAS = dimensional apathy scale. Higher scores on the apathy scale and DAS indicate increased amotivation.

These results indicated that the executive component of motivation and/or spontaneous MW mediates the relationship between motivation and MW. Additional mediation analyses were conducted using several models. Figure 2 presents the graphical results. In Models 1 and 2, the indirect effect was significant, indicating that the two variables significantly functioned as a mediator in the association between AS and MWQ. A comparison via the robust likelihood ratio test between the two non-nested models suggested that Model 2 is superior to Model 1 (robust likelihood ratio = 644, p < 0.001). When the variables were included simultaneously, the indirect effect was again significant (Model 3). However, Model 3 fit worse than Model 2 (robust likelihood ratio = 2924, p < 0.001). The bias-corrected bootstrapped CIs for indirect effects were above 0 in all models (0.05–0.11 in Model 1, 0.17–0.25 in Model 2 and 0.17–0.25 in Model 3).

Mediation Analyses of the Relationship Between the Apathy Scale and Mind Wandering Questionnaire. Note Two mediators were considered, namely, the spontaneous mind wandering scale (Model 1) and executive subscale of DAS (Model 2). Model 3 incorporated them simultaneously. AS = apathy scale; MW-S = spontaneous MW scale, MWQ = mind wandering questionnaire; DAS = dimensional apathy scale and dasEx = executive subcomponent of DAS.

Interim discussion

A person’s MW tendency is related to several factors1,5,14. Intuitively, motivation towards tasks influences the rate of MW during such tasks6,7,8,11. A previous study also identified this association between motivation and MW at the trait level13. However, the underlying mechanism remains unclear.

The significance of trait-level association between motivation and MW could be replicated in Study 1 using a different sample based on a previous report13, which indicated that the association is robust in healthy individuals. This finding is important because this relationship was not intuitive at the trait level. Next, simple correlation analyses indicated that the executive component of motivation and the spontaneous component of MW contribute to the association. The following analyses supported the possibility that these sub-components mediate the association between motivation and MW. Statistically, the executive type of motivation and spontaneous MW partially mediated this association. Their mediating role can also be observed in the model that simultaneously posits the two variables as mediators (i.e. Model 3), although Model 2 displayed superiority in terms of parsimoniousness. Importantly, the result of Model 3 provides knowledge that dasEx entirely mediates the effect of AS on MW-S, whereas MW-S significantly mediates the relationship between dasEx and MWQ. This outline is reminiscent of the executive failure hypothesis of MW3,15. As this hypothesis is in accordance with the traditional perspective: MW is a result of a lapse in attention; participants with low levels of executive function would experience high levels of MW than those with high levels of executive function. Theoretically, this model focuses on spontaneous MW, which should be experienced after the failure of the executive process10,32. This model supports the current results because the executive type of amotivation influenced the occurrence of spontaneous MW, which could contribute to the general association between amotivation and MW at the trait level. Thus, the key psychological component of the association between motivation and MW is executive function.

However, to be precise, dasEx is not a measurement of executive function although it is conceptually clear. Study 2 provides a more direct assessment of executive function and examines its effect on the relationship between motivation and MW using ECS, which is used to assess executive function, especially for inhibition, initiation, and attention control22,23, in addition to confirming the reproducibility of Study 1 in another sample of Study 2.

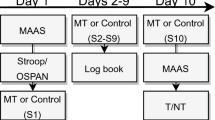

Study 2

Participants

Basically, the recruitment used for Study 2 is similar to that of Study 1. The same data collection company was used to recruit participants for Study 2; however, they were independently recruited. This study estimated that 150 participants would be included for every age group (i.e. 20–29, 30–39 and the like), resulting in 750 participants in total. Again, three lure items were set, where 188 participants did not follow the instructions. Finally, data from 562 participants were analysed (mean age = 45.4 ± 13.7 years; women = 263). Only certain participants (n = 35) were duplicated between the two studies, identified by the ID provided by the data collection agency.

Measurements

Besides the measurements in Study 1, a new measurement was added to assess participants’ executive function.

Scale for executive function

Effortful control scale (ECS)

ECS is a questionnaire used to measure participants’ effortful control similar to executive function22,23. The questionnaire comprises 35 items, including reverse items, which were rated using a 4-point Likert-type scale. Effortful control is a single, latent temperamental construct directly linked to executive function38, which includes sub-components of inhibition (e.g. ‘It is easy for me to hold back my laughter in a situation where laughter wouldn’t be appropriate’ and ‘If I want to, it is usually easy for me to keep a secret’), activation (e.g. ‘I am often late for appointments’ and ‘As soon as I have decided upon a difficult plan of action, I begin to carry it out’), and attention control (e.g. ‘It is very hard for me to focus my attention when I am distressed’ and ‘When I am trying to focus my attention, I am easily distracted’). High scores indicate better executive control functions.

Analyses

The analytical methods used in Study 1 were identical to those used in Study 2, except for the addition of another mediation model for verifying the mediating role of executive function in the relationship between motivation and spontaneous MW (i.e. independent variable = MW, mediator = ECS, and dependent variable = MW-S), which was hypothesised in Study 1. Similarly, bootstrapping (2000 samples) was used besides the conventional z-test to confirm the significance of the indirect effects, which does not require assuming normality of the sample distribution.

Results

Table 2 provides the descriptive information of the results, which are illustrated in Fig. S2. Figure S4 provides the correlation coefficients among the variables.

To replicate the association between motivation and MW at the trait level, this study employed correlation analysis and found that the replication was successful (AS-MWQ: r = 0.25 [95% CI 0.11–0.37], p < 0.001). Moreover, Study 1 results were also reproduced. As Fig. 3A shows, the selective significant associations between AS and MW-S (r = 0.19 [95% CI 0.05–0.32], p < 0.001) and between MWQ and dasEx (r = 0.60 [95% CI 0.50–0.68], p < 0.001) were confirmed. The remainder of the associations were non-significant (ps > 0.05).

Replication of Study 1. Scatter Plots of the Correlations Between Mind Wandering and Motivational Indices (A) and the Results of the Mediation Analyses (B). Note As in Fig. 1, data for non-significant correlations after multiple corrections are only shown within the 95% elliptical confidence region of the multivariate t-distribution in panel A. In panel B, the models were identical as those in Study 1. The solid black line indicates the significant path, while the dashed grey line denotes the non-significant path. AS = apathy scale; MW-S = spontaneous MW scale, MWQ = mind wandering questionnaire; DAS = dimensional apathy scale and dasEx = executive subcomponent of DAS. Higher scores on the apathy scale and DAS indicate increased amotivation.

Additionally, Study 2 re-conducted the mediation analyses conducted in Study 1 to confirm the replicability of Study 1 on the independent samples. As Fig. 3B shows, analyses extended the results in Study 1 through the finding that the association between AS and MWQ was entirely explained by the variance of dasEx, which indicates the possibility of executive function. The bias-corrected bootstrapped CIs for indirect effects were above 0 in all models (0.04–0.11 in Model 1, 0.11–0.20 in Model 2 and 0.11–0.20 in Model 3).

Thus far, the study confirmed the possibility that the key component of the association between motivation and MW is executive function, which in turn causes spontaneous MW. This relationship was tested using a more direct measure of executive function (i.e. ESC). Correlation and mediation analyses revealed that ECS is more strongly associated with MW-S than MW-D (z = 7.83, p < 0.001), although these correlation coefficients were significant (ECS-MW-S: r = − 0.54 [95% CI − 0.59 to − 0.47], p < 0.001; ECS-MW-D: r = − 0.28 [95% CI − 0.35 to − 0.20], p < 0.001). Additionally, ECS mediated the relationship between AS and MW-S (Fig. 4). The bias-corrected bootstrapped CIs for indirect effect ranged from 0.11 to 0.20.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that the trait-level association between motivation and MW is primarily mediated by executive function, which then evokes spontaneous MW. These findings were reliable as per the replicability of the study using a different sample in Study 2.

Previous studies have reported that motivation and MW are temporally related6,7,11. A proposed mechanism of this state-level association indicates that individuals deliberately allow the mind to wander during unmotivated periods. In other words, individuals are expected to deliberately let their mind wander during unmotivated states in daily life. However, the current results did not support this hypothesis. The result is understandable given the dissociation between the trait and state dimensions in motivation and/or MW. Previous studies have also indicated that motivation and MW in fact share a covariance between the trait and state dimensions; however, these dimensions are weakly associated9,13,39. The trait–state relationship is enigmatic and is influenced by several factors, such as memory, metacognitive ability and time or season of the test. The current study provided an insight into understanding the divergence between the trait and state dimensions. Contrary to the hypothesis that amotivation induces deliberate MW, this study found that the lower the level of motivation, the more the mind wanders in a spontaneous fashion at the trait level, whose association depends on executive function.

The concept of the subdivision of motivation in the current study emerged from the perspective of apathy17,18,40. Although the importance of the subdivision in healthy individuals remains unclear, the executive component may be the most important factor of apathy in patients without dementia41,42 and healthy adults19,20. In this study, the subdivision suggested that executive dysfunction may be the mechanism that underlies the association between motivation and MW, which could lead to spontaneous MW at the trait level. Using a more direct assessment of executive function can corroborate this finding. As noted in the Interim Discussion section, the executive failure hypothesis of MW supported the results. Individuals with high levels of executive capacity reported more on-task and less off-task thoughts during experimental tasks compared to those with low levels of executive capacity3,6,14,15. Based on such a clear relationship, this hypothesis suggests that the inability to focus on a task and task-relevant goals could result in MW. Specifically, the experience sampling method found that participants with low levels of executive function experienced high rates of MW in daily life in terms of the effect of executive function on MW at the trait level43. This finding is consistent with the current results. Conversely, several studies have proposed the link between high levels of cognitive capacity and increased MW4,44. This seemingly contrasting phenomenon, explained by executive failure and executive control accounts, are perhaps dependent on a certain context, that is, the demands of the task5,45 (see study46 for another reconciliation). People with high levels of executive skills could adaptively select their mental activities from avoiding MW that leads to deleterious consequences during demanding tasks6,15 to allowing their mind to wander during non-demanding tasks4,14,44. In the latter case, studies have confirmed the adaptive aspect because people could consider the future47 or think in a creative manner48. Based on this account of context regulation hypothesis45, the current study suggests that the introspective nature of a questionnaire survey weights or biases MW during specific tasks in daily life with relatively high demands. As an interpretation, people tend to remember these MW more clearly than the MW during tedious tasks or no task because such MW during tasks in high demands would result in negative consequences. Perhaps this introspective and/or memory bias could explain the absence of correlation between deliberate MW and trait motivation, although there are other possibilities (e.g. people with less motivation at the trait level may lack the motivation to let their mind wander deliberately because deliberate MW needs a cognitive load to a certain extent). Because the specific measures used here cannot support or deny this hypothesis, future research may need to adopt measurements for the contexts that individuals are in when they are MW so as to consider the inference of an introspective bias.

The potential limitations of this study are as follows. First, the causality included in the mediation analyses seems inappropriate because the causal effect of amotivation on executive function may be theoretically questionable, especially for the model shown in Fig. 4. The result should be interpreted as follows: the covariance between executive function and amotivation evokes spontaneous MW and diverts attention from the causal relationship. Second, the application of the apathy subdivision to motivation in healthy individuals may be controversial. Although apathy is clearly a disorder of motivation16 several apathy scales had been initially developed by employing healthy populations18,29,40, one can claim that this application is inadequate. Moreover, the reliability of dasEm was insufficient in both Studies 1 and 2, which was also demonstrated previously29. Further investigation of these points may be required. Third, the retrospective method may bias the results. Besides the aforementioned nuisance effect of memory, such self-reported data would be contaminated with the mood and neurocognitive state during the survey5; moreover, trait-state and survey test inconsistency were observed in MW13,49. Moreover, studies on executive function have demonstrated such a discrepancy50. To draw solid conclusions, an experimental study that utilises task-based assessments for MW (i.e. experience sampling method) and executive function (i.e. Stroop’s task and N-back task) are warranted. Fourth, the characteristics and conditions of the participants were totally unknown, except for age and sex. The study did not conduct screening for cognitive impairment.

Irrespective of these limitations, the current findings can provide meaningful insights for understanding motivation and MW at the trait level and aid in developing interventions to control these tendencies in daily life. Although this study used the correlational approach, its adequate sample size and self-replication provided a solid conclusion that the failure of executive function can explain the association between motivation and MW at the trait level, which may be biased by the use of retrospective methods.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data availability

The datasets collected and/or analysed in this study are not publicly available because a joint research agreement is required for data sharing. However, information is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Killingsworth, M. A. & Gilbert, D. T. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 330, 932 (2010).

Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. The restless mind. Psychol. Bull. 132, 946–958 (2006).

McVay, J. C. & Kane, M. J. Does mind wandering reflect executive function or executive failure? Comment on Smallwood and Schooler (2006) and Watkins (2008). Psychol. Bull. 136, 188–197 (2010).

Levinson, D. B., Smallwood, J. & Davidson, R. J. The persistence of thought: evidence for a role of working memory in the maintenance of task-unrelated thinking. Psychol. Sci. 23, 375–380 (2012).

Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. The science of mind wandering: empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 487–518 (2015).

Unsworth, N. & McMillan, B. D. Mind wandering and reading comprehension: Examining the roles of working memory capacity, interest, motivation, and topic experience. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 39, 832–842 (2013).

Robison, M. K. & Unsworth, N. Cognitive and contextual correlates of spontaneous and deliberate mind-wandering. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 44, 85–98 (2018).

Seli, P., Schacter, D. L., Risko, E. F. & Smilek, D. Increasing participant motivation reduces rates of intentional and unintentional mind wandering. Psychol. Res. 83, 1057–1069 (2019).

Seli, P., Risko, E. F. & Smilek, D. On the necessity of distinguishing between unintentional and intentional mind wandering. Psychol. Sci. 27, 685–691 (2016).

Seli, P., Risko, E. F., Smilek, D. & Schacter, D. L. Mind-Wandering With and Without Intention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20, 605–617 (2016).

Seli, P., Cheyne, J. A., Xu, M., Purdon, C. & Smilek, D. Motivation, intentionality, and mind wandering: implications for assessments of task-unrelated thought. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 41, 1417–1425 (2015).

Phillips, N. E., Mills, C., D’Mello, S. & Risko, E. F. On the influence of re-reading on mind wandering. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 69, 2338–2357 (2016).

Kawagoe, T., Onoda, K. & Yamaguchi, S. The association of motivation with mind wandering in trait and state levels. PLoS One 15, e0237461 (2020).

Kane, M. J. & McVay, J. C. What mind wandering reveals about executive-control abilities and failures. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 21, 348–354 (2012).

McVay, J. C. & Kane, M. J. Conducting the train of thought: working memory capacity, goal neglect, and mind wandering in an executive-control task. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 35, 196–204 (2009).

Marin, R. S. Differential diagnosis and classification of apathy. Am. J. Psychiatry 147, 22–30 (1990).

Levy, R. & Dubois, B. Apathy and the functional anatomy of the prefrontal cortex-basal ganglia circuits. Cereb. Cortex 16, 916–928 (2006).

Radakovic, R. & Abrahams, S. Developing a new apathy measurement scale: Dimensional apathy scale. Psychiatry Res. 219, 658–663 (2014).

Clarke, D. E., Ko, J. Y., Lyketsos, C., Rebok, G. W. & Eaton, W. W. Apathy and cognitive and functional decline in community-dwelling older adults: results from the Baltimore ECA longitudinal study. Int. Psychogeriatr. 22, 819–829 (2010).

Kawagoe, T., Onoda, K. & Yamaguchi, S. Apathy and executive function in healthy elderly-resting state fMRI study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9, 1–7 (2017).

Braver, T. S. et al. Mechanisms of motivation-cognition interaction: Challenges and opportunities. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 14, 443–472 (2014).

Rothbart, M. K., Evans, D. E. & Ahadi, S. A. Temperament and personality: Origins and outcomes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78, 122–135 (2000).

Yamagata, S., Takahashi, Y., Shigemasu, K., Ono, Y. & Kijima, N. Development and validation of Japanese version of effortful control scale for adults. Jpn. J. Personal. 14, 30–41 (2005).

Krosnick, J. A. Response strategies for coping with the cognitive demands of attitude measures in surveys. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 5, 213–236 (1991).

Knofczynski, G. T. & Mundfrom, D. Sample sizes when using multiple linear regression for prediction. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 68, 431–442 (2008).

Maxwell, S. E. Sample size and multiple regression analysis. Psychol. Methods 5, 434–458 (2000).

Starkstein, S. E. et al. Reliability, validity, and clinical correlates of apathy in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 4, 134–139 (1992).

Okada, K., Kobayashi, S., Yamagata, S., Takahashi, K. & Yamaguchi, S. Poststroke apathy and regional cerebral blood flow. Stroke 28, 2437–2441 (1997).

Kawagoe, T., Onoda, K., Yamaguchi, S. & Radakovic, R. Developing and validating the Japanese version of dimensional apathy scale (J-DAS). Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 74, 411–412 (2020).

Mrazek, M. D., Phillips, D. T., Franklin, M. S., Broadway, J. M. & Schooler, J. W. Young and restless: Validation of the Mind-Wandering Questionnaire (MWQ) reveals disruptive impact of mind-wandering for youth. Front. Psychol. 4, 560 (2013).

Kajimura, S. & Nomura, M. Development of Japanese versions of the Daydream frequency scale and the mind wandering questionnaire. Shinrigaku Kenkyu 87, 79–88 (2016).

Carriere, J. S. A., Seli, P. & Smilek, D. Wandering in both mind and body: Individual differences in mind wandering and inattention predict fidgeting. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 67, 19–31 (2013).

Yamaoka, A. & Yukawa, S. Development of Japanese versions of the mind wandering: Deliberate and mind wandering: spontaneous scales. Japanese J. Educ. Psychol. 67, 118–131 (2019).

Frederick, G. & Wallnau, L. B. Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences (Cengage Learning, 2011).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 36, 717–731 (2004).

Vuong, Q. H. Likelihood ratio tests for model selection and non-nested hypotheses. Econometrica 57, 307 (1989).

Merkle, E. C., You, D. & Preacher, K. J. Testing nonnested structural equation models. Psychol. Methods 21, 151–163 (2016).

Sulik, M. J. et al. The factor structure of effortful control and measurement invariance across ethnicity and sex in a high-risk sample. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 32, 8–22 (2010).

Tremblay, P. F., Goldberg, M. P. & Gardner, R. C. Trait and state motivation and the acquisition of Hebrew vocabulary. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Can. Sci. Comport. 27, 356–370 (1995).

Ang, Y.-S., Lockwood, P., Apps, M. A. J., Muhammed, K. & Husain, M. Distinct subtypes of apathy revealed by the apathy motivation index. PLoS One 12, e0169938 (2017).

Feil, D., Razani, J., Boone, K. & Lesser, I. Apathy and cognitive performance in older adults with depression. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 18, 479–485 (2003).

Zgaljardic, D. J. et al. Relationship between self-reported apathy and executive dysfunction in nondemented patients with Parkinson disease. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 20, 184–192 (2007).

Kane, M. J. et al. For whom the mind wanders, and when: An experience-sampling study of working memory and executive control in daily life. Psychol. Sci. 18, 614–621 (2007).

Rummel, J. & Boywitt, C. D. Controlling the stream of thought: Working memory capacity predicts adjustment of mind-wandering to situational demands. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 21, 1309–1315 (2014).

Smallwood, J. & Andrews-Hanna, J. Not all minds that wander are lost: the importance of a balanced perspective on the mind-wandering state. Front. Psychol. 4, 441 (2013).

Smallwood, J. Distinguishing how from why the mind wanders: A process-occurrence framework for self-generated mental activity. Psychol. Bull. 139, 519–535 (2013).

Smallwood, J., Nind, L. & O’Connor, R. C. When is your head at? An exploration of the factors associated with the temporal focus of the wandering mind. Conscious. Cogn. 18, 118–125 (2009).

Baird, B. et al. Inspired by distraction: Mind wandering facilitates creative incubation. Psychol. Sci. 23, 1117–1122 (2012).

Seli, P., Risko, E. F. & Smilek, D. Assessing the associations among trait and state levels of deliberate and spontaneous mind wandering. Conscious. Cogn. 41, 50–56 (2016).

Friedman, N. P. & Banich, M. T. Questionnaires and task-based measures assess different aspects of self-regulation: Both are needed. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 24396–24397 (2019).

Funding

This study was supported by Grant 19K14481 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author confirms sole responsibility for the following: study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawagoe, T. Executive failure hypothesis explains the trait-level association between motivation and mind wandering. Sci Rep 12, 5839 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09824-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09824-3

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.